Since 2005, Inke Arns has been the curator and artist director of Hartware MedienKunstVerein, an institution focusing the cross-section between media and technology into forms of experimental and contemporary art. This year, she was the curator for the exhibition titled alien matter during transmediale festival’s thirty-year anniversary. I had the pleasure of meeting Inke and taking a leisurely stroll with her around the exhibition.

The interview is written as part of a late-night email exchange with Inke a couple of weeks following our initial meeting.

CS: How did the idea come about? In your introductory text you mention The Terminator. Were you truly watching Arnold when alien matter occurred to you as an exploratory concept?

IA: Haha, good question! No, seriously, this particular scene from Terminator 2 (1991) was sitting in the back of my head for years, maybe even decades. It’s the scene where the T-1000, a shape-shifting android, appears as the main (evil) antagonist of the T-800, played by Arnold Schwarzenegger. The T-1000 is composed of a mimetic polyalloy. His liquid metal body allows it to assume the form of other objects or people, typically terminated victims. It can use its ability to fit through narrow openings, morph its arms into bladed weapons, or change its surface colour and texture to convincingly imitate non-metallic materials. It is capable of accurately mimicking voices as well, including the ability to extrapolate a relatively small voice sample in order to generate a wider array of words or inflections as required.

The T-1000 is effectively impervious to mechanical damage: If any body part is detached, the part turns into liquid form and simply flows back into the T-1000’s body from a far range, up to 9 miles. Somehow, the strange material of the T-1000 was teaming up with Jean-Francois Lyotard’s notion of “Les Immatériaux” (1985). Lyotard tried to describe new kinds of matter, that at first sight look like something that we know of old, but in fact are materials that have been taken apart and re-assembled and therefore come to us with radically new qualities. It is essentially alien matter which Lyotard was describing.

CS: You also comment on intelligent liquid and then make reference to four subcategories for the ‘rise of new object cultures’: AI, Plastic, Infrastructure, and the Internet of Things. Is this what makes up ‘alien matter’ to you? Inorganic materials? Simultaneously, HTF The Gardener and Hard Body Trade explicitly and dominantly utilise nature.

IA: Well, the shape shifting intelligent liquid acts more like a metaphor. It is a metaphor for the fact that the clear division between active subjects and passive objects is becoming more and more blurred. Today, we are increasingly faced with active objects, with things that are acting for us. The German philosopher Günther Anders, yet another inspiration for alien matter, described in his seminal book The Obsolescence of Man (Die Antiquiertheit des Menschen) how machines – or computers – are “coming down”, how over time they have come to look less and less like machines, and how they are becoming part of the ‘background’. Or, if you wish, how they have become environment. That’s what I tried to capture in these four subcategories AI, Internet of Things, Infrastructure and Plastic. It is subcategories that reflect our contemporary situation, and at the same time are future obsolete. All of this is becoming part of the big machine that is becoming visible on the horizon. The description that Anders uses is eerily up to date.

Is this alien matter inorganic? Well, yes and no. It is primarily something inorganic as plastic could be described as one of the earliest alien matters – its qualities, like, e.g., its lifespan, are radically different from human qualities. However, it is something that increasingly merges with organic matter – Alien in Green showed this in their workshop that dealt with the xeno-hormones released by plastic and how they can be found in our own bodies. They did this by analyzing the participants’ urine samples in which they found stuff that was profoundly alien.

In the exhibition, everything is highly artificial, even if it looks like nature, like in Ignas Krunglevicius’ video Hard Body Trade or Suzanne Treister’s series of drawings/prints HFT The Gardener. The ‘natural’ is becoming increasingly polluted by potentially intelligent xeno-matter. We are advancing into murky waters.

CS: There is no use of walls in the exhibition, other than Video Palace, standing as a monumental structure made out of VHS tapes. Why did you decide to exclude setting up rooms or walls for alien matter?

IA: I knew right from the beginning that I wanted to keep the space as open as possible. Anything you build into this specific space will look kind of awkward. This is also how I make exhibitions in general: Keeping the exhibition space as open as possible, building as few separate spaces as possible in order to allow for dialogues to happen between the individual works. For alien matter we worked with raumlaborberlin, an architectural office that is known for its unusual and experimental spatial solutions and that has been working with transmediale for quite some time now. I have worked with them for the first time and I am super happy with the result. We met several times during the development process, and raumlabor proposed these amazing tripods you can see in the show. They serve as support for screens and the lighting system. (Almost) nothing is attached to the walls or the ceiling. raumlabor were very inspired by the aliens in H.G. Wells’ War of the Worlds – where the extraterrestrials are depicted with three legs and a gigantic head. Even if the show is not about aliens I really liked the idea and the appearance of these tripods. They look at the same time elegant, strange, and through their sheer size they are also a bit awe-inspiring. Strange elegant aliens so to speak to whom we have to look up in order to see. At the same time they are ‘caring’ for the exhibition, almost as if they were making sure that everything is running smoothly.

CS: What can you tell me about the narrative behind Johannes Paul Raether’s Protekto.x.x. 5.5.5.1.pcp.? You mentioned that it was originally a performance in the Apple Store, nearly branding the artist a terrorist.

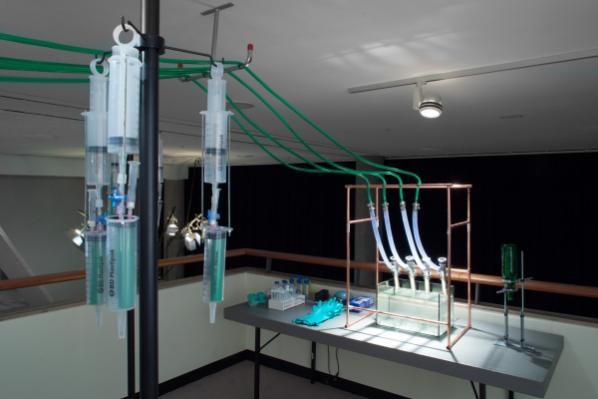

IA: Correct. The figure central to the installation is one of the many fictional identities of artist Johannes Paul Raether, Protektorama. It investigates people’s obsession with their smartphones, explores portable computer systems as body prosthetics, and addresses the materiality, manufacturing, and mines of information technologies. Protektorama became known to a wider audience in July 2016 when a performance in Berlin, in which gallium—a harmless metal—was liquefied in an Apple store, led to a police operation at Kurfürstendamm. In contrast to the shrill tabloid coverage, the performative work of the witch is based on complex research and visualizations, presented here for the first time in the form of a sculptural ensemble including original audio tracks from the performance. The figure of Protektorama stems from Raether’s cyclical performance system Systema identitekturae (Identitecture), which he has been developing since 2009.

CS: Throughout the exhibition there is an awareness that technological singularity can and possibly will overcome the human body and condition. In the context of the exhibition, do you think that we may be accelerating towards technological and machinic singularity? As humans, are we already mourning the future?

IA: The technological singularity is a trans-humanist figure of thought that is currently being propagated by the mathematician Vernor Vinge and the author, inventor and Google employee Ray Kurzweil. This is understood as a point in time, and here I resort to Wikipedia, “at which machines rapidly improve themselves by way of artificial intelligence (AI) and thus accelerate technical progress in such a way that the future of humanity beyond this event is no longer predictable.” The next question you are probably going to ask is whether I believe in the singularity.

CS: Do you?

IA: Whether I believe in it? (laughs) The singularity is in fact a kind of almost theological figure. Technology and theology are very close to one another in a sense. The famous American science fiction author Arthur C. Clarke once said that any sufficiently developed technology can’t be differentiated from magic. I consider the singularity to be an interesting speculative figure of thought. Assuming the development of technology were to continue on its course as rapidly as it has to date, and Moore’s Law (stating that computing performance of computer chips doubles every 12-24 months) retained its validity, what would then be possible in 30 years? Could it really come to this tipping point of the singularity in which pure quantity is transformed into quality? I don’t know. What is interesting right now is that instead of the singularity, we are faced with something that the technology anthropologist Justin Pickart calls the ‘crapularity’: “3D printing + spam + micropayments = tribbles that you get billed for, as it replicates wildly out of control. 90% of everything is rubbish, and it’s all in your spare room – or someone else’s spare room, which you’re forced to rent through AirBnB.” I also suggest to check out the ‘Internet of Shit’ Twitter feed.

CS: You come from a literary background. Noticing the selection and curation of alien matter, it becomes clear that you love working with narratives. Do you feel as though your approach of combining narrative and speculative imaginations is fruitful and rewarding?

IA: I do (if I didn’t I wouldn’t do it). I think narrative – or: storytelling – and speculative imaginations are powerful tools of art. They allow us to see the world from a different perspective. One that is not necessarily ours, or that is maybe improbable or unthinkable today. The Russian Formalists called this (literary) procedure ‘estrangement’ (this was ten years before Bertolt Brecht with his ‘estrangement effect’). Storytelling and/or speculative imaginations help us grasping things that might be difficult to access from our or from today’s perspective. It’s like an interface into the unknown. Maybe you can compare it to learning a foreign language – it greatly helps you to understand your own native language.

CS: On a final note, I’d like to revisit a conversation we had during transmediale’s opening weekend. We spoke about a potential dichotomy or contention between the discourse followed by transmediale and that of the contemporary art world, using the review by The Guardian about the Berlin Biennial as an example. Beautifully written, albeit you seemed to disagree with some points made – particularly at the notion enforced by the writer that works shown there, similar in nature to the works in alien matter, are not ‘art’. Could you elaborate on your thoughts?

IA: You are mixing up several things – let me try to disentangle them. I was referring to the article “Welcome to the LOLhouse” published in The Guardian. The article was especially critical of the supposed cynicism and sarcasm it detected in the Berlin Biennale curators’ and most of the artists’ approaches. Well, what was true for Berlin Biennale was the fact that it showed many younger artists from the field of what some people call ‘post-Internet’ art. This generation of artists – the ‘digital natives’ – mostly grew up with digital media. And one of the realities of the all pervasive digital media is the predominance of surfaces. The generation of artists presented at the Berlin Biennale dealt a lot with these surfaces. In that sense it was a very timely and at the same time a cold reflection of the realities we are constantly faced with. I felt as if the artists held up a mirror in which today’s pervasiveness of shiny surfaces was reflected. It could be interpreted as sarcasm or cynicism – I would rather call it a realistic reflection of contemporary realities. And it was not necessarily nice what we could see in this mirror. But I liked it exactly because of this unresolved ambivalence.

About transmediale and the contemporary art world: These are in fact two worlds that merge or mix very rarely. I have often heard from people deeply involved in the field of contemporary art (even some friends of mine) that they are not interested in transmediale and/or that they would never attend the festival or go and see the exhibition. And vice versa. This is mainly due to the fact that the art people think that transmediale is too nerdy, it’s for the tech geeks (there is some truth in this), and the transmediale people are not interested in the contemporary art world as they deem it superficial (there is some truth in this as well). For my part, I am not interested in preaching to the converted. That’s why I included a lot of artists in the show that have never exhibited at transmediale before (like Joep van Liefland, Suzanne Treister, Johannes Paul Raether, Mark Leckey). However, albeit the borders, the fields have become increasingly blurred. It is also visible that what is coming more from a transmediale (or ‘media art’) context clearly displays a greater interest in the (politics of) infrastructures that are covered by the ever shiny surfaces (that bring along their own but different politics).

I could continue but I’d rather stop, as it is Monday morning, 3:01 am.

You can also read a review of alien matter, available here.

alien matter is on display until the 5th of March, in conjunction with the closing weekend of trasmediale. Don’t snooze on the last chance to see it!

All in-text images are courtesy of Luca Girardini, 2017 (CC NC-SA 4.0)

Main image is a still from the movie The Terminator 2 (1991)