This show is curated jointly by Helen Sloan of SCAN and the John Hansard Gallery, Southampton. There is both curatorial interest in the technological aspects of the work as well as the subject matter of the war artist. Sloan was approached by the Arts Council in terms of initiating a project for the ‘Interact’ series of commissions, on which she worked with David Cotterrell. In 2007, Coterrell went to Afghanistan as artist-in-residence for a month in a field hospital. At his residency in 2008, at SEOS (now Rockwell Collins), a company that makes flight simulators. He explored the nature of representation itself, and particularly ‘the suspension of disbelief’. This relates to our relationship with digital data, and how often we regard it as more real, due to its nominal representation of reality and our use of this as information.

What appear to be ‘A-life critters’, are in fact scaled down human forms. Trawling across a dust-sculpted landscape, the real of the chalk dust intersects with the virtual projections of the A-life program which is mapping the movement of these forms to the reality of the sculpted landscape.

David Cotterrell doesn’t want to show pictures of the atrocities of war, but instead focuses on the complex experience of lived space in territorial combat and its mapping. He presents a kind of ‘topo-analysis’ of an imaginary space, with nominal figures located and moving in spatial relationship to one another. In Observer Effect the gallery viewer triggers the movement of the virtual entities who are attracted by a ‘sphere of influence’ to the viewers position in the gallery space. In this way, the phenomenon of space, location and relationship and the concomitant fear of combat, casualty, and mortality are implicit in the context of this exhibition.

Cotterrell has chosen to interrogate image making using technology, much as Vilém Flusser recommended, together with a lack of acceptance of the ‘normal’ indexical uses of photography and film about which he is ambivalent, although he used these media in Afghanistan.

What these works achieve is the proposition of a ‘possible world’ where depersonalisation is understood as part of the virtual, nominal, mapped collective fantasy, which somehow then relates to the changing ‘world view’ of the Western citizen. It is also where the reference to science fiction comes from, ‘Monsters of the Id’ referring to the film Forbidden Planet. Science fiction is perhaps referred to in order to re-conceptualise our thinking as part of this Western view. In this sense it is about empowering us to think differently about the portrayal of conflict itself in the twenty-first century and to understand it as lived experience within specifically managed environments.

This is largely achieved through Cotterrell’s translation of his own experience as war artist in Afghanistan. He seems to want his experience to affect the viewer in a way which is different from that which he witnessed, to a reliance on the imagination instead, provoked by the portrayal of the landscape and militarised environment. Instead the exploration is one of attempting to convey the sense of isolation he felt in the military field hospital.

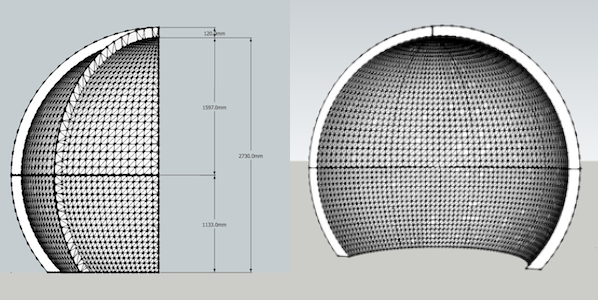

What becomes apparent on seeing this work, is that we are being presented with data objects, which we are then encouraged to relate to, as though they are the nominal representation of real subjects. It is significant that the work is realised with new technology. All three main works in the show explore a similar landscape but use three different projection systems. In Observer Effect the system relates to interaction with the gallery visitor who influences the installation in spatial relativity, through a device that senses and then calculates, through the algorithms and maths of a game engine, their relationship to the virtual space. Alternatively, in Searchlight 2, there is a synthesis between real and virtual as the figures traverse the landscape. He has said in relation to this piece that ‘from a great distance we lose empathy with the figures crossing the landscape’. In Apparent Horizon, the viewer encounters a semi-immersive relationship with video projected onto specially designed hemi-spheres, a view of the horizon, and a lengthy period of waiting for something to happen, which captures the tension between periods of violence. In this sense the artist has worked both as a war artist and as an artist using and developing the application of new technologies.

He talked about computer programming having a tendency towards ‘megalomaniac control’, and that the installation was addressed towards ‘how an audience inhabits a gallery’, with no ‘fetishizing of computers’. The residency at SEOS has obviously affected the nature of the technology employed in the work, with two ‘black boxes’ enabling aspects of the projections, as well as the hemi-spheres as immersive hardware. The system of Observer Effect is adaptive and therefore responds to the accumulated impact of viewers in the gallery. He talked about how a commercial games company would find it easy to make, but for him it had been a steep learning curve.

Cotterrell was able to return to Afghanistan in early 2008, due to support from the RSA, and was therefore able to look at the territory of the desert ‘outside the bubble of the military’, which had given him a limited understanding of the environment, a sense of dislocation, and the apprehension of casualties brought from the desert war zone. On this occasion he grew a beard and was able to disguise himself sufficiently so that he could interact with different groups of Afghani people and to gain a ‘pluralism of experience’, as on this occasion he was not part of the chain of command. In this second journey, he was ‘low value’ and therefore able to wander more freely.

Initially, he found it difficult to deliver art work in response to what he had experienced in Afghanistan. He was aware of the historical dilemma of the conflict between medicine and war. But for him, the trauma was ‘quieter’ and involved loss of identity. For example, the twenty-one year old soldier who after severe injury was ambiguous about what would happen for the rest of his life.

He found the operating theatre at the field hospital was ‘like a stage set’, and he took photographs of the surgeons, but found that the documentation ‘didn’t document’ sufficiently his lived experience. At one point he left a video camera running, documenting the arrival of casualties and then, when he was back at home, he edited the footage and left only the moments when attendant individuals ‘allowed their guard to drop’. He questioned though, whether ‘it was right to document trauma’. This left him with the ‘impossibility of conveying content’.

As war artist he has chosen to explore the military and political relationships with the technological portrayal of soldiers and civilians within a territorial combat zone. This is sufficient for Cotterrell in order to convey the sense of isolation and the particular landscape of Afghanistan. In this way, apprehending the virtual or nominal as a way of perceiving what could be real, and is real in a conflict situation, puts the viewer in a complex position, of both suspending disbelief and recognising the construct. The final work Monsters of the Id, includes in a small installation an army tent, desk and military communications equipment. This conjures up an image of Cotterrell’s experience as a war artist, although in fact it is his portrayal of how we might think of it – as naïve in other words.

For the team of curators, gallery staff, and the artist, it has been curatorially important to work within the gallery space and Cotterrell claims that the ‘virtual can only really be understood in a gallery context.’ This is enabled through the works being not fully immersive so that you can stand back and reflect. As such the show is all about ‘the manipulation of imagery’ informed by the residencies in Afghanistan and at SEOS.

The exhibition continues till 31 March 2012 at the John Hansard Gallery, Southampton

Women, Art & Technology is a series of interviews that seeks to find different perspectives on the current voice of women working in art and technology. The series continues with curator Sarah Cook.

Sarah Cook is a curator and writer based in Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, and co-author with Beryl Graham of the book Rethinking Curating: Art After New Media (MIT Press, 2010). She is currently a reader at the University of Sunderland where she co-founded and co-edits CRUMB, the online resource for curators of new media art, and where she teaches on the MA Curating course. Most recently she curated the Mirror Neurons exhibition that is part of the AV Festival running through till March 31, 2012, in New Castle.

Rachel Beth Egenhoefer: Over the last few years you have curated a number of exhibitions in relation to festivals of media art. Could you start by giving us a brief description of the AND (Abandon Normal Devices) Festival and your involvement in it last year?

Sarah Cook: My involvement in the AND Festival was to curate a small group exhibition for the galleries at Liverpool John Moore’s University Gallery (in the Art and Design Academy Building). The exhibition was a part of AND but was also curated for the crowd of academics attending the Rewire conference which I was co-chairing. Rewire was the Fourth International Conference on the Histories of Media Art, Science and Technology. A three-day, peer reviewed, international event, the conference had over 150 speakers and three keynote lectures including one by Andrew Pickering, author of the book The Cybernetic Brain. The exhibition, Q.E.D., included seven projects all of which questioned how we can know anything but looking at documentation of it (a problem for art historians of course!). In 2011 the AND Festival had as its theme questioning belief and the structures of belief, so this exhibition complemented their huge and diverse programme.

I had been involved in previous Media Art Histories conferences – having co-curated the exhibition “The Art Formerly Known As New Media” for the first one, Re:Fresh!, which was held in Banff in 2005.

RBE: Could you give us a few examples of work from your exhibition that you felt really abandoned normal devices or methods of production and presented new perspectives?

SC: I selected works in which the artists might have abandoned normal ways of making art, to undertake experiments of sorts, experiments demonstrating phenomena in the world. (Q.E.D. is from the Latin ‘Quod Erat Demonstrandum’ meaning what was to have been demonstrated or what was required to be proved). I wanted a show in which skepticism was the norm, and a perfectly valid methodology for artists to employ as they go about investigating, modeling or representing the world around them.

So there was documentation of Norman White and Laura Kikuaka’s 1988 project Them Fuckin’ Robots — an attempt to create one male and one female electro-mechanical sex machine, without sharing in advance any information about materials, function, or how they would connect.

Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg and Sascha Pohflepp’s work-in-progress, Yesterday’s Today, was part of their Southampton University commission investigating the limits and possibilities of models for describing knowledge. They started with the oldest predictive model known to science, and a very British one at that, the weather forecast, and attempted to cool the gallery space to the predicted temperature for the day. There was a heatwave in Liverpool that week in September, so it was a great to experience reality and a model of reality simultaneously.

Axel Straschnoy, along with his many collaborators at the Robotics Institute at Carnegie Mellon University (Ben Brown, Garth Zeglin, Geoff Gordon, Iheanyi Umez-Eronini, Marek Michalowski, Paul Serri, Sue Ann Hong), showed the documentation of their attempts to create a robot that performs art and a robot that watches and appreciates performance art. The informal video interviews with the artificial intelligence engineers discussing how a robot might want to make art are brilliant and often funny.

RBE: I understand your work with AND has lead to a new project recently launched with the AV Festival.

SC: Yes, I have curated an exhibition for the AV Festival, taking place across Newcastle, Sunderland and Middlesborough through March 2012. The show is at the National Glass Centre in Sunderland and is called Mirror Neurons. While AV Festival has a theme of Slowness, Mirror Neurons seeks to question time delay, media processing, and the time it takes for our cognition to kick in when we are in the presence of art – interactive, reactive or not. One of the pieces which was in Q.E.D is in this show also: Scott Rogers’ Self-Flowing Flask – a glass object made based on a drawing by 17th century scientist and inventor Robert Boyle, shown alongside a digitally created animation of it. There is a real sense of confusion by viewers when they see the object: Does it work? Could it work? How would it work? And then when they see the animation they have to work out if it is real or not.

RBE: You mention “Slowness” as the theme for the AV Festival. “Slowness” is also a trending theme right now with slow food, slow craft, etc. How do you see slowness in relationship to technology which is usually portrayed as something “fast”?

SC: The theme of slowness was chosen by AV Festival director Rebecca Shatwell, and so I was glad to leave exploration of that notion to her and her programme, which is stacked with fantastic works of art in moving media (film and video) and sound and performance. In the exhibitions I’ve curated for AV Festival, which include both Mirror Neurons, and a new commission from New York-based artist Joe Winter – also on view at the National Glass Centre in Sunderland – I’ve focused less on the theme of slowness than on the human action of recognising time passing, the lag between our perception or understanding of time and space, and our acknowledgement of our own actions within it.

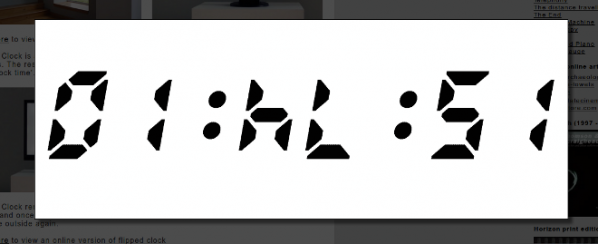

There are some works in Mirror Neurons which seem, on the surface, to be about time, but which play with the possibility of shifting time, or at least reprocessing it or subjecting it to a new set of rules, with computer technology. By the same token, these works then also implicate you, the viewer, in the time of their action, in your realization of what it is those works are ‘doing’. For instance, Thomson & Craighead’s work Flipped Clock, is a standard computer digital clock, but with the numerals rotated, so that it is defamiliarised and causes you to do a double take and spend a moment working it out. And Michael Snow’s WVLNT (Wavelength for those that don’t have the time) was 45 minutes, now 15!!, in my mind collapses time and space, by superimposing scenes from his 1967 structuralist film – not speeding it up but overlaying it, and seeing through it from beginning to end within the same frames.

Last comes Joe Winter’s work (which was also included in Q.E.D in the form of wall-based works which appear to be representations of astronomical or geological phenomena, but are made from standard office photocopier images or meeting room whiteboards). For the AV Festival I commissioned him to make a new work for the National Glass Centre also. …a history of light: variable array is comprised of a series of sculptural works which appear like lovingly-made office in-box trays to hold documents. Only they are ranged on white pedestals across a sunny balcony space, and contain coloured craft paper and plates of glass produced by Cate Watkinson. The idea is that over the time of the exhibition (1 March to 20 May) the sunlight will fade the coloured paper, through the plates of glass, and abstract images, based on the patterns and effects in the glass, will result. The images are both created, and destroyed, by the light, over time. Joe’s previous works have all dealt in conceptions of time – deep time, geological time, astronomical time and media time – and his work takes its aesthetics from the media and technology which surrounds us, in mundane spaces such as the office cubicle or the classroom, which while might contain ‘fast’ technology, such as computers, also contains quite ‘slow’ or old or timeless technology, such as chalk, or paper.

RBE: This interview is going to be part of a series of interviews with women working in Art & Technology. What do you consider to be important today about being a woman working in art & technology? Do you think it is still useful to discuss the female voice in the field?

SC: I suppose there is an interesting generational break in the art and technology world at the moment as regards women’s work. I am keenly aware of (and tremendously grateful for) the work of a slightly older generation of women than me, including curators, who set up networks, facilitated international exchange, built the platforms which new media artists can work on. This generation also includes important women artists who worked with technology, gaining access to labs and high tech equipment to make work – some understanding it technically better than others, many working with the help of (often male) programmers.

In the exhibition Mirror Neurons is the work of Catherine Richards, a media artist from Canada whose work I wrote about in my PhD dissertation. For her career to date she has investigated how our bodies are plugged in to the electromagnetic spectrum which surrounds us, making Faraday Cages and copper-woven blankets to insulate us from these signals. Other of her work makes visible the connection between us, as electric beings, and our techno-environment. For the work on view in Sunderland, which was made in 2000, she worked with expert vacuum physicists and scientific glass producers at the National Research Council of Canada. For other works she has collaborated with software engineers (it was an early web-based project of hers which led in part to the invention of the software Java). She plays an important role also teaching art students, reminding them of the history of media art, which is often overlooked, and of where these technologies we take for granted come from.

Now that technologies are more ubiquitous there is a younger generation of women artists working in the field, under their own initiative. For instance, the new Pixel Palace programme at the Tyneside Cinema included three women artists in residence earlier this year – working in sound, film and digital media. Sometimes I do wonder what the preceding generation is up to; have they been able to keep up with new technologies or stuck with older ways of doing things? Have they changed tactics and after working so hard to establish themselves in what was then a rather male technological world, decided to move on? Like any field, the art and technology world will have its share of ‘old boys’ but I suppose in my work I strive to always value the collaborative relationships I have with artists and other curators, of any generation and any gender.

Also read – Woman, Art & Technology: Interview with Lynn Hershman Leeson By Rachel Beth Egenhoefer.

“It is not accidental that at a point in history when hierarchical power and manipulation have reached their most threatening proportions, the very concepts of hierarchy, power and manipulation come into question. The challenge to these concepts comes from a redsicovery of the importance of spontaneity – a rediscovery nourished by ecology, by a heightened conception of self-development, and by a new understanding of the revolutionary process in society.” Murray Bookchin. Post-scarcity and Anarchism (1968).

The rise of neo-liberalism as a hegemonic mode of discourse, infiltrates every aspect of our social lives. Its exponential growth has been helped by gate-keepers of top-down orientated alliances; holding key positions of power and considerable wealth and influence. Educational, collective and social institutions have been dismantled, especially community groups and organisations sharing values associated with social needs in the public realm. [1] Bourdieu.

In this networked society, there are controversies and battles taking place all of the time. Battles between corporations, nation states and those who wish to preserve and expand their individual and collective freedoms. Hacktivist Artists work with technology to explore how to develop their critical and imaginative practice in ways that exist beyond traditional frameworks of art establishment and its traditions. This article highlights a small selection of artists and collaborative groups, whose work is linked by an imaginative use of technology in order to critique and intervene into the opressive effects of political and social borders.

In June 2000, Richard Stallman [2] when visiting Korea, illustrated the meaning of the word ‘Hacker’ in a fun way. When at lunch with some GNU [3] fans a waitress placed 6 chopsticks in front of him. Of course he knew they were meant for three people but he found it amusing to find another way to use them. Stallman managed to use three in his right hand and then successfully pick up a piece of food placing it into in his mouth.

“It didn’t become easy—for practical purposes, using two chopsticks is completely superior. But precisely because using three in one hand is hard and ordinarily never thought of, it has “hack value”, as my lunch companions immediately recognized. Playfully doing something difficult, whether useful or not, that is hacking.” [4] Stallman

The word ‘hacker’ has been loosely appropriated and compressed for the sound-bite language of film, tv and newspapers. These commercial outlets hungry for sensational stories have misrepresented hacker culture creating mythic heroes and anti-heroes in order to amaze and shock an unaware, mediated public. Yet, at the same time hackers or ‘crackers’ have exploited this mythology to get their own agendas across. Before these more confusing times, hacking was considered a less dramatic activity. In the 60s and 70s the hacker realm was dominated by computer nerds, professional programmers and hobbyists.

In contrast to what was considered as negative stereotypes of hackers in the media. Steven Levy [5], in 1984 published Hackers: Heroes of the Computer Revolution [6]. In three parts, he writes about the canonical AI hackers of MIT, the hardware hackers who invented the personal computer industry in Silicon Valley, and the third-generation game hackers in the early 1980s. Yet, in this publication, what has had the most impact on hacker culture and is still used widely as a guideline by many is the ‘hacker ethic’. He identified this Hacker Ethic to be a code of practice consisting of key points such as that “all information is free”, and that this information should be used to “change life for the better”.

1. Access to computers—and anything which might teach you something about the way the world works—should be unlimited and total. Always yield to the Hands-on Imperative!

2. All information should be free.

3. Mistrust authority—promote decentralization.

4. Hackers should be judged by their hacking, not bogus criteria such as degrees, age, race or position.

5. You can create art and beauty on a computer.

6. Computers can change your life for the better.

Levy’s hacker ethic promotes the idea of performing a duty for the common good, an analogy to a modern day ‘Robin Hood'[ibid]. Proposing the concept that hackers are self-reliant whilst embracing a ‘healthy’ anti-authoritarian stance, combined with free and critical thinking. Proposing that hackers should be judged by their ability to hack, and presenting hacking as an art-form. Levy also says that the Free and open source software (FOSS) movement is the descendant of the hacker ethic. However, Levy’s hacker ethic has often been quoted out of context and misunderstood as to refer to hacking as ‘breaking’ into computers. This specifically prescribed role, denies the wider and creative context of what hacking is and could be. It does not have to be just about computer security.

This leads us to ‘crackers’. All crackers hack and all hackers hack. But, crackers are seen as second rate wannabe hackers by the older generation of hackers. The Black Hat Hacker or cracker designs and releases malicious code, gathers dangerous information and brings down sensative systems. The White Hat Hacker hunts down and destroys malicious code, and the casual hacker who hacks in order to learn information for his or her own curiosity; both generally dislike ‘Black Hats’ and ‘Crackers’, and tend to view them as computer criminals and dysfunctional juveniles. Lately, crackers have also been labeled as ‘script kiddies’. As a kind of snobbish insult, it refers to those who are not capable of building or programming their own tools, but tend to use scripts and programs written by others to perform their intrusions. To add to the confusion we also have the term ‘Grey hat’. Which refers to a hacker acting between black hat and white hat. Indeed, this could demonstrate where art hacktivists reside, challenging the trappings of the traditional concept of goody and baddy.

“There is another group of people who loudly call themselves hackers, but aren’t. These are people (mainly adolescent males) who get a kick out of breaking into computers and phreaking the phone system. Real hackers call these people ‘crackers’ and want nothing to do with them.” [7] Raymond.

“The basic difference is this: hackers build things, crackers break them.” [ibid] Raymond.

But before we judge,

let’s view a snippet of the \/\The Conscience of a Hacker/\/ by +++The Mentor+++

Written on January 8, 1986.[8]

“This is our world now… the world of the electron and the switch, the

beauty of the baud. We make use of a service already existing without paying

for what could be dirt-cheap if it wasn’t run by profiteering gluttons, and

you call us criminals. We explore… and you call us criminals. We seek

after knowledge… and you call us criminals. We exist without skin color,

without nationality, without religious bias… and you call us criminals.

You build atomic bombs, you wage wars, you murder, cheat, and lie to us

and try to make us believe it’s for our own good, yet we’re the criminals.”

The term ‘Hacktivism’ was officially coined by techno-culture writer Jason Sack in a piece about media artist Shu Lea Cheang published in InfoNation in 1995. Yet, the Cult of the Dead Cow [9] are also acknowledged as defining the term. The Cult of the Dead Cow are a group of hackers and artists. They say the Hacktivism phrase was originally intended to refer to the development and use of technology to foster human rights and the open exchange of information.

Hacktivism techniques include DoS attacks, website defacement, information theft, and virtual sabotage. Famous examples of hacktivism include the recent knocking out of the PlayStation Network, various assistances to countries participating in the Arab Spring, such as attacks on Tunisian and Egyptian government websites, and attacks on Mastercard and Visa after they ceased to process payments to WikiLeaks.

Hacktivism: a policy of hacking, phreaking or creating technology to achieve a political or social goal.

“Hacktivism is a continually evolving and open process; its tactics and methodology are not static. In this sense no one owns hacktivism – it has no prophet, no gospel and no canonized literature. Hacktivism is a rhizomic, open-source phenomenon.” [10] metac0m.

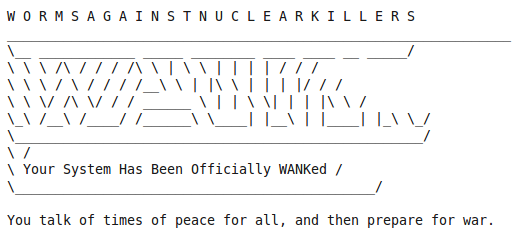

The practice or behaviour of Hacktivism is at least as old as Oct 89 when DOE, HEPNET and SPAN (NASA) connected to (virtual) networked machines world wide. They were penetrated by the anti-nuclear group WANK worm.

WANK penetrated these machines and had their login screens altered to…

HACKING BORDERS: Examples of Art Hacktivism & Cultural Hacking…

“Radical groups are discovering what hackers have always known: Traditional social institutions are more vulnerable in cyberspace than they are in the physical world. And some members of the famously sophomoric hacker underground are becoming motivated by causes other than ego gratification.” [11] Harmon.

Hacktivism, exploits technology and the Internet, experimenting with the immediacy of distributable networks as a playful medium for independent, creative and free expression. There has been a gradual and natural shift from net art (and net.art) into Hacktivism. Net Art in spirit, has never really been just about art being viewed on a web browser alone. Some of the very same artists whose artwork involved being shown in browsers and making code behind the browser as part of the art, have also expanded their practice outside of the browser. One such artist is Danja Vasiliev, “Fifteen years ago WWW was something very new in Russia and besides the new dial-up aesthetics and world-wide means it brought a complete new layer of existence – “netosphere”, which made my youth.” Vasiliev very soon moved on from playing with browsers into a whole new territory. [12]

Danja co-founded media-lab moddr_ in 2007, a joint project at Piet Zwart Institute alumni and WORM Foundation. Based in Rotterdam moddr_ is a place for artists and hackers, engaging with critical forms of media-art practice. He collaborated with Gordan Savicic and Walter Langelaar from the moddr.net lab on the project Web 2.0 Suicide Machine, which lets you delete your social networking profiles and kill your virtual friends, and it also deletes your own profile leaving your profile image replaced by a noose.”The idea of the “Web 2.0 Suicide Machine” is to abandon your virtual life — so you can get your actual life back, Gordan Savicic tells NPR’s Mary Louise Kelly. Savicic is the CEO — which he says stands for “chief euthanasia officer” — of SuicideMachine.org.” [13]

Just like another project called ‘Face to facebook’ that stole 1 million facebook profiles and re-contextualized them on a custom made dating website (lovely-faces.com), set up by Italian artists Paolo Cirio and Alessandro Ludovico, whom also just so happens to be editor in chief of Neural magazine. Web 2.0 Suicide Machine, had to close its connections down regarding its Facebook activities after receiving a cease and decease letter from Facebook. [14]

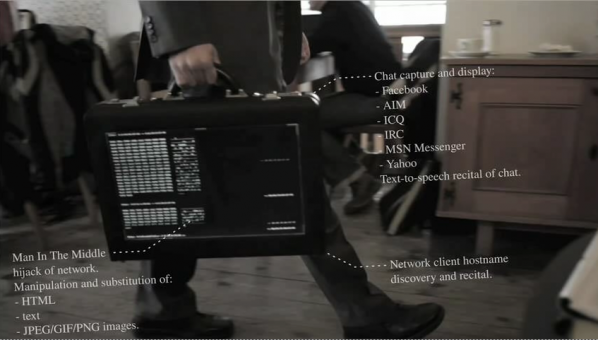

Julian Oliver and Danja Vasiliev teamed up and formed the mysterious group Men in Grey. The Men In Grey explore our online vulnerabilities by tapping into, intervening into wireless network traffic. Observing, tracing and copying what we do. This hack then redisplays our activities back to us, showing the data of our online interactions.

At first no one (except myself & a few others) knew who they were. When they first arrived on the scene I started an interview with them and then suddenly, I was asked to hold back due to their antics on the Internet and interventions in public environments receiving much coverage. They were not sure how it would pan out for them. Partly due to the anonymous nature of their project, and also because of the sudden impact of the larger hacktivist group Anonymous getting much press in commercial media themselves.

“Men In Grey emerge as a manifestation of Network Anxiety, a fearful apparition in a time of government wiretaps, Facebook spies, Google caches, Internet filters and mandatory ISP logging.” M.I.G

“Spooks are listening into calls, just like they always have,” said Eric King of London’s Privacy International, in an e-mail. “With A5/1 being broken—you can decrypt and listen into 60 calls at once with a box smaller than a laptop.” [15]

Later they won the Golden Nica (1st prize) Interactive Arts category, Prix Ars Electronica in 2011. In a show called Project Space — M.I.G. — Display of unknown, quarantined equipment hosted at the Aksioma Project Space Komenskega, Ljubljana 2011. The statement read:

“The particularly threatening quality of the Men In Grey equipment is its apparently invasive nature; it seems able to penetrate – and even hack into – virtually any electronic device in its reach. While we are all aware of the wire-tapping and data retention done by the government (along with the spying carried out by corporations like Facebook and Google), Men In Grey seem to operate with a range of tools and techniques well beyond those that are currently known to be in use.”

Hacktivism involves many different levels of social intervention and engagement. Whether it is to do with direct action, self-referential geekiness, obscure networked antics, crtical gaming, or peer 2 peer and collective change. Hacktivists challenge defaults put in place by other people, usually the systems imposed upon them and the rest of us by authority. Even though the subjects themselves may be concerning serious matters, humour and playfulness are both essential ingredients.

“A promising tactic for the early Situationists was the unpredictable yet forceful potential of play — what anthropologist Victor Turner termed the “liminoid,” or the freeing and transformational, moments of play when the normal roles and rules of a community or society are relaxed.” [16] Dovey & Kennedy.

One group crossing over from the digital into physical and social realms, is Tiltfactor. [17] Their form of intervention is not necessarily about causing political controversy, but is engaged in reaching people through games of play. Experimenting with social everyday contexts, making games that tackle less traditional topics, such as public health, layoffs, GMO crops. One of the many games creating awareness on these subjects, is POX “Our game actually helps a player understand how a disease can spread from one place to another and how an outbreak might happen” says Mary Flanagan. [18]

A local public health group called Mascoma Valley Health in the New Hampshire region of the US approached Tiltfactor with the problem of the lack of immunization. “At first, a game about getting people immunized seemed like one of the most “un-fun” concepts imaginable. But that sinking feeling of impossibility almost always leads to good ideas later.” [19] Flanagan.

“Geopolitical space has always been a conflicted and fragile topic. Borders and frontiers are changing so fast, that sometimes it seems that our sociopolitical status can change from “citizen” to “immigrant” from one moment to another, or simply live under the “immigrant” status all your life. We’re getting used to words like refugees, enclaves, war, borders, limits –and the list has no end.” Ethel Baraona Pohl & César Reyes

Ricardo Dominguez collaborated with Brett Stalbaum, Micha Cardenas, Amy Sara Carroll & Elle Mehrmand, on (TBT) (and others), on a hand-held mobile phone device that aids crossers of the Mexico-US border. An inexpensive tool to support the finding of water caches left in the Southern California desert by NGO’s for those crossing the border.

“The entire group of artists who are part of Electronic Disturbance Theater 2.0/b.a.n.g. lab working on the Transborder Immigrant Tool (TBT) was being investigated by UCSD and 3 Republican Congressmen starting on January 11, 2010. Then I came under investigation for the virtual sit-in performance (which joined communities statewide against the rising students fees in the UC system and the dismantling of educational support for K–12 across California) against the UC Office of the President (UCOP) on March 4, 2010. This was then followed by an investigation by the FBI Office of Cybercrimes.” [20] Ricardo Dominguez.

In an interview with Lawrence Bird Dominguez discusses that the TBT is still developing as a gps tool, but infers that it is not just a tool but also ‘border disturbance art’, consisting of different nuances existing as part of a whole with other factors at play. Such as a hybrid mix of things, objects and expressions “artivism, tactical poetries, hacktivism(s), new media theater, border disturbance art/technologies, augmented realities, speculative cartographies, queer technologies, transnational feminisms and code, digital Zapatismo, dislocative gps, intergalactic performances, [add your own______].” [ibid]

“Borders are there to be crossed. Their significance becomes obvious only when they are violated – and it says quite a lot about a society’s political and social climate when one sees what kind of border crossing a government tries to prevent.” [21] Florian Schneider

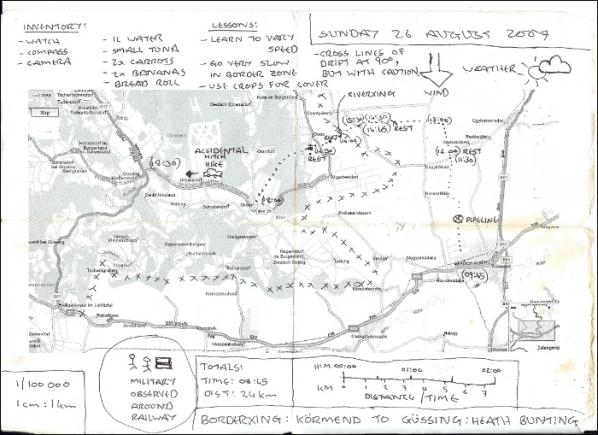

National borders are front-lines of political and social friction. The exerience of asylum-seekers and political migrants reflect some of the most significant issues of our time. Immigration is a toxic issue and unpopular with voters. Bunting’s BorderXing Guide, plays on the fear of invisible alien hordes of people crossing our borders illegally.

The context of this work fits well with issues about borders, whether it is about creating borders online or physical environments. Only those needing to cross a border are allowed access to the site, it is limited to ‘social clients’ who have a static IP (Internet Protocol) address and who, most notably, have gained the artist’s confidence. Such as peer activists and immigrants using libraries, colleges, cultural centres. The site allows those who would other wise end up crossing borders in harmful ways, such as in containers, on the backs of (and underneath) lorries and planes.

Heath Bunting’s BorderXing Guide website primarily consists of documentation of walks that traverse national boundaries, without interruption from customs, immigration, or border police. The work comments on the way in which movement between borders is restricted by governments and associated bureaucracies. It is a manual written not at distance like a google map, but by foot. A physical investigation, involving actually going to these places; trying these discovered routes out and then sharing them with others. A carefully calculated politics of public relations.

“The Feral Trade Café is more than just an art space that’s a working café, it’s about provoking people to question the way big food corporations operate by looking at the journey of the food we end up scraping into our pampered bins.” [22] Gastrogeek

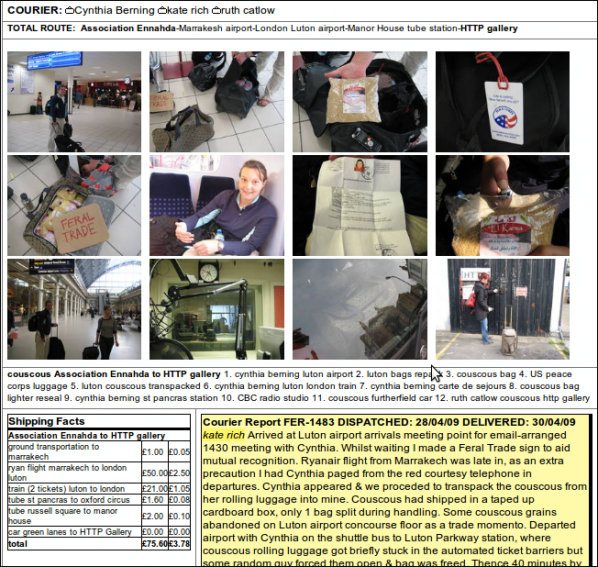

Feral Trade uses social and cultural hand baggage to transport food based items between cities, often using other artists and curators as mules. Feral Trade products (2003-present), alongside ingredient route maps, bespoke food packaging, video and other artefacts from the Feral Trade network. The goods rangefrom coffee from El Salvador, hot chocolate from Mexico and sweets from Montenegro, as well as locally sourced bread, vegetables and herbs.

Kate Rich uses the word ‘feral’ as a process refering to being deliberately wild, as in pigeon, as opposed to romantic nature wild as the wolf. It is an unruly wild, shitting everywhere, disruption and annoyance in contrast to ‘official’ human structures and connected infrastructures. Feral Trade freight operates largely outside commercial channels, using the surplus potential of social, cultural and data networks for the distribution of goods. Working with co-operatives, small growers and food producers.

The Feral Trade Courier is a live shipping database for a freight network running outside commercial systems. The database offers dedicated tracking of feral trade products in circulation, archives every shipment and generates freight documents on the fly.

Every shipment is different and has its own story of how and where it was delivered from. Also included is information on who the carriers are with details about producers and their local culture as contextual information. The product packaging itself is also a carrier of information about social, political context and discussions with producers and carriers.

![Feral Trade at Furtherfield's Gallery (2009) [23] Link to exhibition](http://www.furtherfield.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/3657297700_42b1c26014_b.jpg)

Since the rise of the Internet individual and collective actions are symbiotically connected to the every day. In a world transformed, common people have access to tools that can change ‘our’ cultures independently; sharing information, motivating actions and changing situations. We know of the Arab Spring, the Occupy movement, Anonymous and Wikileaks and how successful they have been in exploiting technology and social networks. Technology just like any other medium is a flexible material. By tweaking, breaking and remaking ‘something’ you can re-root it’s function, change its purpose.

The links between these mass social movements and the artists here are not just relating to technology’s use but, a shared critique at the same enemy, neo-liberalism.

“”Neo-liberalism” is a set of economic policies that have become widespread during the last 25 years or so. Although the word is rarely heard in the United States, you can clearly see the effects of neo-liberalism here as the rich grow richer and the poor grow poorer.” [24] Martinez & Garcia.

At the same time as highlighting the continual privatization of human society. This form of art practice shows us the cracks of where a social divide of gate-keeping has maintained power within the Western World’s, traditional art structures. We now realize that the art canons we have been taught to rely on as reference are more based around privelage, centralization and market dominance rather than democratic representation or even just pure talent. Hacktivist artists adapt and recontextualize with a critical approach, towards a larger and more inclusive context beyond their own immediate selves. Demonstrating a respect and use of autonomy, and an awareness of social contexts and political nuances, freeing up dialogue for new discussions which include a recognition of social contexts, as a vital ingredient and valued resource in art. Re-aligning, reconfiguring the defaults of what art is today.

Featured image: Lynn Hershman Leeson Portrait (Photo Credit: Ethan Kaplan)

Woman, Art & Technology is a new series of interviews on Furtherfield. Over the next year Rachel Beth Egenhoefer will interview artists, designers, theorists, curators, and others; to explore different perspectives on the current voice of woman working in art and technology. I am honored to begin this series with an interview with Lynn Hershman Leeson, a true pioneer in the field who has recently produced !Women Art Revolution- A Secret History.

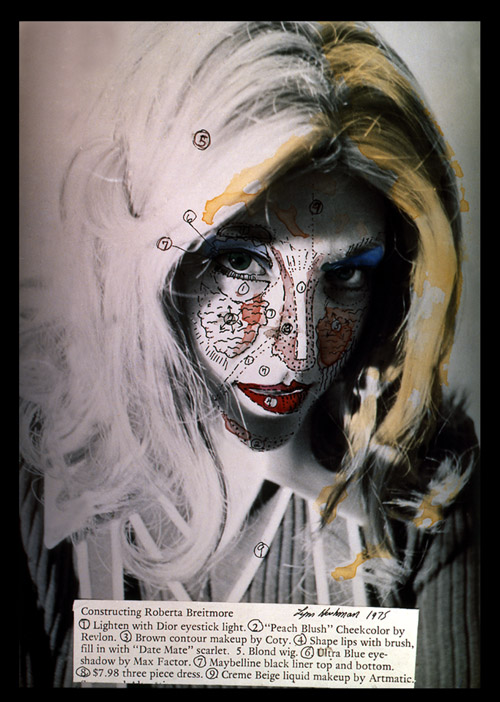

Over the last three decades, artist and filmmaker Lynn Hershman Leeson has been internationally acclaimed for her pioneering use of new technologies and her investigations of issues that are now recognized as key to the working of our society: identity in a time of consumerism, privacy in a era of surveillance, interfacing of humans and machines, and the relationship between real and virtual worlds. She has been honored by numerous prestigious awards including the 2010-2011 d.velop digital art and 2009 SIGGRAPH Lifetime Achievement Awards. Hershman also recently received the 2009 John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellowship, an award which supported her latest documentary film !Women Art Revolution – A Secret History.

Rachel Beth Egenhoefer: Your most recent project is the film “!Women Art Revolution” which you have been collecting materials for and working on for the past forty years. Why is now the time to present it as a finished work?

Lynn Hershman Leeson: TECHNOLOGY! The film is one narrative, but I’ve put the entire 12,428 minutes online through Stanford University Library, making all the narratives and aterials accessible, so in effect there are no out takes. Also the RAWWAR org archive/website allows people to continue the story online. So the story continues to grow beyond the single narrative, which technology allows us to do now.

Additionally, I wanted to push out into public view the graphic novel, curriculum guide, and the story to affect the legacy while women who created the movement could be appreciated.

RBE: Can you expand on how you see the RAWWAR story continuing online? Or maybe what is the goal of the archive/website? Do you envision people adding to it?

LHL: Yes, it was made specifically so that people, especially younger generations will be able to add information. At the Walker Art Center, they have scanning stations and are training people how to upload work onto the site. My hope is that people from around the world will add materials and it will be a living repository of this type of growing and accessible information.

RBE: The film has been touring in the U.S., what has the response been?

LHL: Incredible. It has been in over 60 cities, and standing ovations in San Francisco, Houston, Toronto, Sundance, Berlin and Mexico City. People seem deeply affected by this secret history and seem to appreciate knowing about it.

RBE: Has the response varied either with geography or current events?

LHL: Not really, it seems vibrantly appreciated worldwide despite it being about women in America.

RBE: Can you explain the grammar behind the title “!Women Art Revolution”?

LHL: If you mean why the ! first, it was so we would be listed first, rather than under W. It didn’t work, but that was why we did it originally. It also is a wild exclamation at the start, which is what the movement was.

RBE: The film is described as presenting the relationships between the Feminist Art Movement and the anti-war and civil rights movements, showing how historical events sparked feminist actions. Do you see any connections to be made with the current Occupy Movements?

LHL: Yes, absolutely. In some ways because it is about how the disempowered and invisible people were able to gain their place in culture; how people who had their voices silenced were able to amplify their message and subverted social systems, with work that expressed censorship, freedom of expression, social justice and civil rights and directly made political change. It is an inspiring story of reinvention.

The goals were clearer than with Occupy. But the disenfranchised edges of culture is similar.

RBE: A lot of your early works dealt with issues of identity. How do you think the notion of identity has changed over the years?

LHL: It has become more technological, more global, more cyborgian. We now, because of the internet are linked globally and that has resulted in a “hive mind” and in turn, that seems to be a cohesion and holding together the individual fracturing that had occurred over the last two decades

RBE: Can you expand on the idea of the “hive mind that seems to be holding together the individual fracturing”? What makes up the hive, what is fracturing us? Is this good or bad or neither?

LHL: The hive is social media and people who participate in the Internet grammar. There is a congealing through access to information. As individuals, I think we have been fracturing, rupturing, split for decades and have become multi faceted and multi taskers. But there’s a price in the lack of personal cohesion that results. I think that having a common reference or ‘hive’ is a very good thing, as it tests our idea of ‘reality’, and serves as a hub of communication.

RBE: Do we make our own hives? Or are those defined for us (either by others/ FaceBook/surveillance/ etc)?

LHL: We are all part of global re-patterning that is happening live on a global scale and it is naive to assume we can act independently or not be connected or affected. We are constantly challenged, influenced by peripheral and pervasive information and in turn we have become fodder for surveillance and digital integration.

RBE: Some contemporary artists and thinkers have been critical of our online selves and physical selves. Sherry Turkel for instance has described people as “performing themselves” online by constantly updating Facebook profiles, tweets, etc to show an ideal version of ourselves. Can you draw any distinctions between virtual, physical, and performative selves?

LHL: I think we perform ourselves every day, not only on social media, but in all interactions. I do not think all images or versions of ourselves are ideal. There is absolutely a difference between real/physical and virtual selves. They each have a context, reference and function. As far as being performative, that depends upon the distinction used for how it is used. One can, in fact, consider life itself and everything one does as performance.

RBE: This interview is going to be part of a series of interviews with women working in Art & Technology. What do you consider to be important today about being a woman working in art & technology?

LHL: Ada Lovelace wrote the first computer language, Mary Shelley envisioned artificial intelligence, Hedy Lamar invented spread spectrum technology, which led to cell phones. Women have been enormously prescient in visioning and affecting the future of the world through technological linkage systems.

RBE: Do you think it is still useful to discuss the female voice as a separate voice in the field?

LHL: I think the female voice is critical in all aspects of the future and should not be limited to a category.

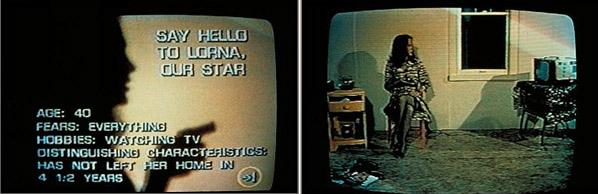

RBE: One of your earlier works, LORNA, depicts a woman who never leaves her apartment and becomes more and more fearful as she watches ads and news on the TV. Some might say television media has gotten far worse since the 80s in both fear mongering and controlling conversations. What do you think about the current state of the media?

LHL: Right, the idea of media as totally affecting our outlook has shifted. Media is no longer omniscient! The 99% are activating their voices and warbling into existence. There are other problems with social media… deeper ones that splay into the cracks of fractured identities and insist on more disruption and lack of focus. But perhaps that is what is affecting our constantly changing evolution.

RBE: If LORNA were around today what would she be thinking or doing in her little 1 room apartment?

LHL: Blogging and all forms of social media including excessive and obsessive shopping, no doubt. She would probably not really be agorophobic either. She would, however, probably be paranoid. She would use a webcam and notice all the ones surrounding her no matter where she moved.

RBE: Do you have hope for change in the future?

LHL: Hope? It is inevitable. I believe in the next generation! They always, in their amnesiac optimism re invent the future in ways that can’t be predicted.

RBE: You have been involved in academia for some time, what do you think is important to be teaching in the Universities right now?

LHL: Independent thinking and creativity, the maintenance of ethics and a profound sense of humor!

RBE: Do you have any new projects you are working on?

LHL: Yes, at least 3 .A new film which is part 3 of my trilogy about the evolution of the human specis, a new installation that uses scanned beating heart cells, and a long term project about Tina Modotti.

Find our more on Lynn Hershman Leeson and Woman Art Revolution here: http://www.lynnhershman.com/http://womenartrevolution.com/

The Philosophy Of Software

Code and Mediation in the Digital Age

David M Berry

Palgrave Macmillan, 2011

ISBN 9780230244184

http://lab.softwarestudies.com/2011/04/new-book-philosophy-of-software-code.html

“The Philosophy Of Software” is an ambitious book by David Berry, who has turned his attention from the social relations and ideology of software (in “Rip, Mix, Burn”, 2008) to the question of what software means in itself. The philosophy that he has in mind isn’t the mindless political libertarianism attributed to hackers or the twentieth-century foundational mathematics that is the basis for the structure of many programming languages. It is a serious and literate philosophical reading of software and its production.

Software is an important feature of contemporary society that is rarely considered as a phenomena in its own right by philosophers. Software permeates contemporary society, Berry gives the examples of Google’s profits and the “financialisation” of the economy through software as examples of software’s importance in this respect. In reading this review on a screen you have used maybe a dozen computers, each containing multiple programs and libraries of software directly involved in serving up this page. Digital art and cyberculture often use and discuss software and philosophy (or at least Theory), but usually to illustrate a point about something other than software. The software itself is rarely the subject.

Rather than devote each chapter to a different philosopher’s views on software or adopting a pre-existing description of software Berry develops a novel and insightful philosophical approach to understanding and considering software. After providing an introduction to the foundational ideas and culture of software (Turing, Manovich, Cyberpunk), Berry presents a way of thinking through different aspect of software. The source code, the comments, the compiled program. Each stage and product of the lifecycle of software is given a philosophical context.

Heidegger emerges as the philosopher whose ideas first underwrite Berry’s approach to software. Latour and, in a surprising way, Lyotard play pivotal roles in later chapters. If these are not philosophers you were well inclined towards before then you are in for a pleasant surprise.

Berry presents some typographically appealing and culturally interesting code in order to demonstrate different features of the production of software. The swearing placed in Microsoft’s Windows source code comments by its programmers will mirror the frustration of many of its users. The Diebold voting machine code that illustrates the assumed social and gender roles of its human subjects show that code is very much a product of the social biases of its human authors.

Much of the code illustrated in the book is code poetry or obfuscated code. These are double-coded programs, where source code that can be run by a computer is written and formatted to be not just understandable but evocative and meaningful to human readers as something read rather than run. As with the comments in the Windows and Diebold code, a criticism that might be levelled at such code is that such textual decoration does not affect the compiled (or executed) form of the code.

But comments and formatting are what Berry refers to as commentary code and delegated code in his grammar of code. It has been said that code is written primarily for human beings to read and only secondarily for computers to execute, and obfuscated or poetic code is regarded as high art by many programmers. It must exemplify some of code’s salient features to them, and so it can be used to do so to a more general audience. And the cultural assumptions of code can survive from its source code into its execution and interface: witness the relief of many of Diaspora’s users than “Gender” was a free-form text field rather than a simple binary choice of “Male” or “Female”.

The final chapter on network streams provides a strong critical philosophy of social networking and other software that reduces human experience to a stream of software representations of events. After discussing what it means for a human being to be a “good stream”, Husserl’s idea of “comets” as a precedent for lifestreams and Lyotard’s idea of the stream (both of which predate the streams of the Internet by many years), Berry presents the idea of Dark Streams as a way of resisting the demands of Web 2.0. I would single this out as the most timely and invigoration section of the book and a must-read for anyone involved in producing, consuming, or critiquing networked software culture.

What doesn’t the book cover? There is no visual coding or livecoding. Berry explicitly avoids “screen essentialism”, where the output of code is concentrated on to the exclusion of its production and execution, but despite following programs from their writing through compilation to first assembly code then machine language, running software and algorithms (at the micro level) are not considered, nor (at the macro level) are the architectures of applications or of operating systems. Nor is testing except in passing. But this fits with the emphasis of the book on code as text, and the framework that it provides can be extended to these topics. Hopefully by Berry.

“The Philosophy Of Software” is particularly inspiring as a spur to further research. Each page is brimming with references in the style of the academic papers that many of the chapters were first produced as and whilst this style can be distracting at first (compared with popular science books for example) it is ultimately rewarding and gives the reader any number of fascinating leads to follow up.

What is important about “The Philosophy Of Software” is that it really is about what it claims to be about. Rather than trying to shoehorn software into an existing philosophical or political agenda it considers software as a thing in itself and finds those philosophers and philosophical ideas that best address the vitally important phenomenon of software. However much philosophy, computer science or cybercultural theory you may know this is a book that will set you thinking about software anew.

The text of this review is licenced under the Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0 Licence.

“Festival of Ideas For A New City” organized by the New Museum, The Architectural League, The Bowery Poetry Club, C-Lab, Columbia University Center for Architecture, Cooper Union, The Drawing Center, NYU Wagner, PARC Foundation, Storefront for Art and Architecture, and the Swiss Institute blossomed like spring in New York City from May 4 – 8th, setting out to “harness the power of the creative community to imagine the future city and explore the ideas destined to shape it.”

Keynotes addressing the issues were architect Rem Koolhaas, virtual reality inventor Jaron Lanier, and former President of the National University of Columbia, and former Mayor of Bogota, Antanas Mockus. A StreetFest set up along the Bowery with over 100 local grassroots organizations and small businesses “presenting model practices and products in a unique environment.” Over 100 projects, events, performances and walking tours expanded on the Festival’s themes.

Rem Koolhaas with OMA and The New Museum showcased CRONOCAOS, an exhibit examining the growing “empire” of preservation and destruction and the consequences of how we build, rebuild and remember. What is the role of preservation on the art world? As larger and larger spaces are repurposed for art from industrial spaces they focus on the “apocalyptic sublime,” mimicking Hollywood and B movies. Oddly enough Koolhaas noted, this increase in preservation closely parallels the rise of Wall Street and tourism.

There were panels on “The Heterogeneous City,” “The Networked City,” “The Reconfigured City,” and “The Sustainable City.” At night curator Anna Muessig’s Flash:Light Nuit Blanche event included murals along the Bowery, art projections on Nolita and Lower East Side buildings, and music and performances including projects on the facade of the New Museum and St. Patrick’s Old Cathedral in Little Italy. There was also a 3D video installation Civilization reinterpreting Dante’s Diving comedy.

Jaron Lanier’s Keynote address on “The Networked City” at the Great Hall at Cooper Union reiterated many of the themes in his new book, “You Are Not A Gadget.” Not one to follow any set path, Lanier began his talk by playing a Laoitian “Ban Lao” (Ban Bang Sai Kai) bamboo wood pipe. He declared the simple reed flute was one of the first holders of digital information, even older than the abacus, because each reed object and note is turned on and off just like a series of digital 0’s and 1’s. The Ban Lao, traded across the Silk Route was noticed by the Greeks and Romans, and influenced the development of the pipe organ. The pipe organ was automated and turned into a player piano, a programmable loom, and finally became the origins of Charles Babbage’s computer.

Computers have gotten better Lanier explained, processing more and more bits, but humans still have more precise acuity at the level of quantum physics. They can respond to just one photon. He then veered off topic discussing the first computer scientist Alan Turing who used computers to crack codes during World War II. Persecuted for being gay, he was injected by authorities with female hormones which gave him breasts and made him suicidal. Just like Snow White, he killed himself by eating a poisoned apple.

He then veered back on track saying using computers as metaphors to the human condition is an irrelevant, outdated metaphor. The brain is not a CPU, and eyes and ears are not USBs. A better metaphor is thinking of the head as a spy submarine performing spy missions. You are constantly moving your head seeking out data, not passively seeing it. Your visual system is sensitive to minute differences. A musical instrument is an additional instrument to the sensory motor loop that makes perception possible. Can we build digital tools that are as sensitive as we are? This, he noted, was one of the key questions now facing computer scientists.

New technologies are usually developed to become weapons. But many important inventions were first developed for music. Musical bows existed before arrows, and guns developed from the casting of metal bells. Even Hewlett Packard’s first object was a musical synthesizer. Music is a driver with innovation taking place around making sounds.

In order to make his lecture relevant to the “Networked City” theme of the festival, Lanier discussed his favourite thing about New York City, that the same sense of acuity as applied to musical instruments also applies to personal interactions. More diversity means you have more chance of connecting with someone who will change your life. The fates of people in New York are guided by their activities. Its important that the fates concern an extra world of human to human contact.

In such a huge network context people are sensitive to subtle motions in each other, and can identify subconscious communication we don’t really know about. Contrast that to sound networking, where digital music does not give you the subtle minute accuracy of acoustic sound. People who only communicate virtually are spinning their wheels in place. When we connect to each other through digital representations we lose some form of expression.

Lanier proselytized for the necessity of the “head and the heart”, insisted technology needs to bring better jobs to society than the ones they are destroying. The basic social contract he said was turned back 11 years ago when advertising became the new way to get information. Sergey Brin, the co-founder of Google was the one who started it. Because digital technology is cheaper, cheaper just gives this stuff away for advertising. But, when you take the products of people’s hearts and minds, such as their music and literature, and give them away for free this becomes a problem. When you put effort into a promotion on line you get the illusion of benefits, but you actually lose relative advantage. This is because the true customers of a social networking site like Facebook is not you, you are actually the product of Facebook. You are sold and the customer pays to influence events. This is the difference between overt and covert information with Lanier stating, “The official business of computation is advertising.” At some point though, there is nothing to advertise. If cars can drive themselves, what happens to truck drivers? Or if 3D machines make fabrications they make manufacturing obsolete.

The Japanese are creating elder care robots. We are making ourselves unemployed. The fashion of making everything free leads us down a path from a city of dreams to a cry of despair. We have to figure out a way to change our relationship to information technology, instead of chasing after users and followers and making more money. Ending his lecture he declared, “We must humanize digital architecture – We must see beyond fads.” And then he played a little ditty on dual Gypsy flutes.

“Only when people are able to use computers to produce their own data does information communication technology become genuinely empowering.” – James Wallbank

Furtherfield is committed to delivering on promise of the Zero Dollar Laptop manifesto with a series of workshop programmes with different community groupw. The Zero Dollar Laptop, is a recycled laptop running Free Open Source Software (FOSS) that is fast and effective- now and long into the future; repurposing otherwise redundant technology, gathering dust in bedrooms and offices across the country.

Pilot workshops with the clients of St. Mungo’s Charity for Homeless People ran for twelve weeks in 2010, where participants learned about using their laptop from core of installing their own operating system to customising their own machines, writing articles and creating images to share and publish via social media. Download the full report pdf here.

The next steps are to implement the Zero Dollar Laptop at a European scale in coordination with European media labs. The initiative is gaining momentum, with interest from Budapest, Nantes, Madrid, and Brussels Visit the Zero Dollar Laptop Blog here.

The project is part of Furtherfield’s Media Art Ecologies programme.

HTTP Gallery is pleased to host LAB4 by Hedva Eltanani, an exploration of communication between two places using streaming media and web applications. It is another step in a series of LABs that explore digital technology and audience interaction. It is part of Heltanani’s research on digital performance and the way it affects audience experience.

LAB4 is a game that challenges the audience to bend the boundaries of space, interaction and intimacy. The two locations, HTTP Gallery in London and The Poly Centre in Falmouth, are linked via live-feed technology, using webcams and web applications. Eltanani will lead a series of activities, such as ‘truth or dare’, which challenges elements of group dynamics and technology – the aim is to engage the two audiences and help participants bond within each group.

How intimate will it go? The participants are invited to deepen the connection by keeping their community active using web applications.

BE PART OF THE EVENT IN LONDON

Doors open at 8:30pm

More info and documentation :

http://arthubfalmouth.blogspot.com/

http://vs4rslab.wordpress.com/

Featured image: People watching and being watched across virtual space

Rachel Beth Egenhoefer considers her Commodore 64 Computer and Fischer Price Loom to be defining objects of her childhood. She creates tactile representations of cyclical data structures in candy and knitting and is currently researching the intersection of textiles, technology, and the body.

Events at HTTP >

Other Related Events >

Rachel Beth will be working as an Artist in Residence at HTTP, Furtherfield’s Gallery and lab space in April 2008. She has been brought to UK from San Francisco as part of the Distributed South initiative, which is a network intended to raise awareness of the considerable activity in media arts in South of UK. Through residencies and collaborative events co-curated by SCAN and Space Media, Distributed South seeks to develop and build collaborations and networks in media arts and all are welcome to take part. Egenhoefer’s residency consists of several key parts – experimental studio time to create new work at the University of Brighton, presenting workshops and lectures across the south of England, a commissioned exhibition at Lighthouse Brighton, all culminating with time spent in residence at Furtherfield.

Currently Rachel Beth is working in the studio on ideas comparing tactile knitting to intangible computer code and how the body interacts and moves with both. In addition to building a knit zoetrope, casting the space between body and machine in candy, she has also been tracking the motion of knitting needles in both physical and virtual space and knitting with the Nintendo Wii. Her time at Furtherfield will be used to continue exploring these ideas while interacting with the larger community and audiences Furtherfield brings.

Higher Education Student Day

Wednesday April 15, 1:00-4:00pm

Rachel Beth will present her work and professional practice from the residency to higher education students

This event is free however advanced booking is necessary.

Networking Event and Residency Closing Party

Configurations: Technology and Textiles Networking Afternoon

25 April, 3.30 – 6pm, HTTP Gallery (Booking essential)

You are invited to share ideas, discuss and develop future working around art work that investigates the relationship between new technology, traditional making techniques and transformative political actions. Anna Dumitriu, Ele Carpenter, Nicola Naismith and Rachel Beth Egenhoefer will present their work using diverse approaches to the making of work using new technology alongside textiles, followed by a “Long Table Discussion”.

The “Long Table Discussion” is an experimental public forum developed by performance artist Lois Weaver. It is a hybrid performance, installation and roundtable discussion designed to facilitate informal conversations on serious topics encouraging everyone to contribute. Previous “Long Table Discussions” include conversations on Women and Prisons, Human Rights and Performance and Manufacturing Bodies.

This event is free however advanced booking is necessary. To book places please email Aaron, visibilityATfurtherfieldDOTorg.

Closing Party for Rachel Beth Egenhoefer 6pm – 9pm (all welcome): Party to celebrate the close of Rachel Beth Egenhoefer’s residency at Furtherfield/HTTP Gallery and providing an opportunity to discuss her work and experiences during the residency.

Rachel Beth Egenhoefer’s residency and Configurations is part of Distributed South an initiative co-curated by SCAN and Space Media. The residency and event is funded by the Arts Council England, University of Wales, University of Brighton, Lighthouse Brighton with support from Furtherfield.org, Textile Futures Research Group (TFRG) and University of the Arts London.

71, Ashfield Rd, London N4 1NY

Click here for map and location details

Distributed South www.distributedsouth.org.uk

www.rachelbeth.net

www.elecarpenter.org.uk

www.nicolanaismith.co.uk

www.annadumitriu.co.uk

Candy & Code

Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) London _Textile Futures Research Group

Monday March 17, 2008, 6:30-8:30pm

Presentations from Rachel Beth Egenhoefer, Barbara Rauch & Nicola Naismith

Following by a panel discussion with the artists and Dr Jane Harris, Director of TFRG, Helen Sloan, Director of SCAN.

Exhibition of New Work

Lighthouse Brighton

March 20- April 5, 2008

Opening Reception: Thursday March 20, 6:00-9:00pm

Talk on Residency and Distributed South (with Rachel Beth Egenhoefer and Helen Sloan) with an opportunity to view the exhibition: Thursday March 27, 7:30pm, doors open at 7

Rachel Beth’s residency for Distributed South is funded by the Arts Council England, University of Wales, University of Brighton, Lighthouse Brighton and supported by SCAN, Space Media, Furtherfield.org, Textile Futures Research Group (TFRG) and University of the Arts London.