3 October 2019 – 5 January 2020, Daily. Free Entry

The roar of an airplane is a familiar sound for many parts of west London, home to one of the busiest airports in the world and the subject of a new exhibition, Air Matters at Watermans Arts Centre in Brentford, just a few miles away from Heathrow.

Echoing the experience of hearing an aircraft in action, sound itself plays an integral part in the show and leads with The Substitute (2019) by Hermione Spriggs and Laura Cooper. Through overhead speakers outside the main entrance, visitors are greeted by an authoritative voice musing on the fate of local flocks in an airspace strictly controlled by humans and their contraptions, intermittently reciting names of affected birds like a tribute, and ultimately urging listeners to “work with nature” which sets a critical tone.

The audio installation is reminiscent of public announcements at airports, a strategy that continues into the foyer with Frequency (2019) by Louise K Wilson. It features intimate anecdotes of air travel through resonance devices on a skylight roof where planes might fly by at any moment. Speaking softly akin to ASMR, one person wonders about the destinations of travellers, while another recalls vivid memories of flights that seem traumatic, bouncing back and forth between excitement and anxiety.

The theme reaches its crescendo inside the gallery, with a mixture of ambient sounds reverberating across the space from Ascending Composition I (For Planes) (2019) by Kate Carr, an atmospheric concoction of incidental noises recorded around Heathrow including birds, markets, and trains on tracks. With pocket-sized media players attached to deconstructed speakers on strings of fabric, the installation documents an intervention that already took place when the work itself flew up on balloons blasting whispers from the ground, a small but meaningful gesture challenging the sonic waves of jumbo jets that dominate the surrounding sky and soundscape.

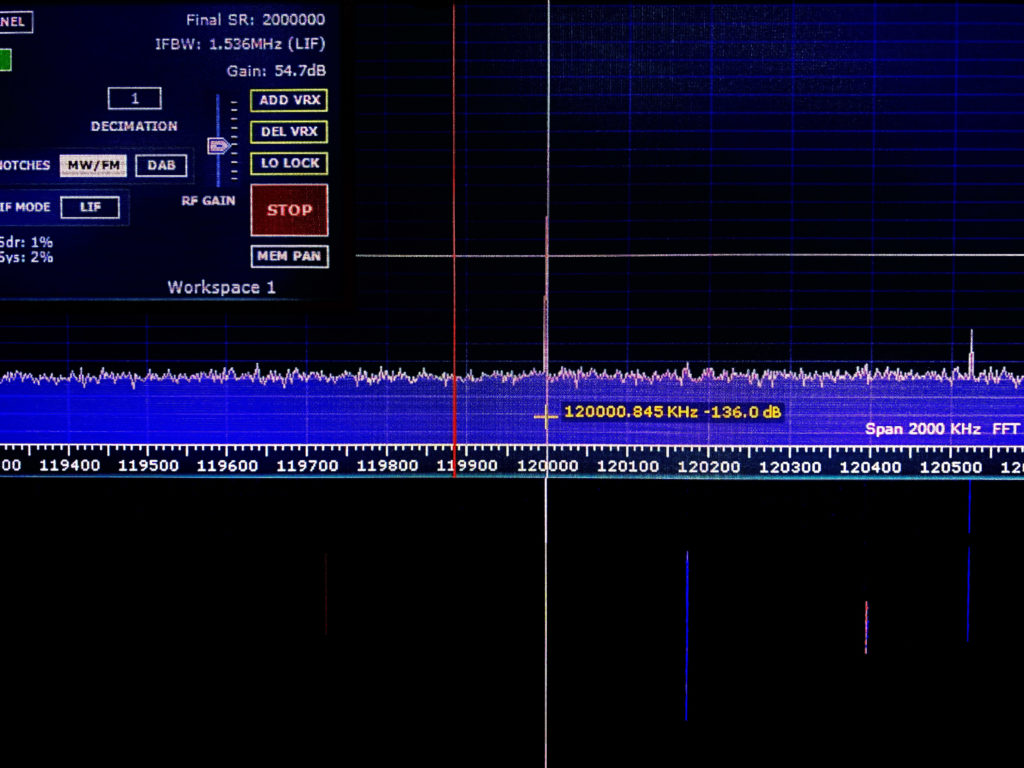

This act of defiance flows into Skyport (2019) by Magz Hall, a mixed media installation with a set of frequency scanners emitting an unsettling static. The title refers to a pirate radio station based along a Heathrow flightpath in the 1970s, illustrated with archival images and texts from an attempt to reclaim airwaves colonised by traffic control and engine noise. The work emulates this spirit with an LCD screen broadcasting airport channels as visual wavelengths, the contents of which are protected as classified information in UK law, consequently questioning ownership, access, and authority over radio frequencies.

The symphony of sounds become unavoidable throughout, and there is a possibility that it might grow vexing for some, perhaps more so for the people that work here who may not have a choice but to hear it again and again. Yet, as irksome as that might be, it is a crucial part of what makes this show effective. The audible pieces collectively transform the spaces into simulations of airport lounges and peripheral towns, simultaneously mimicking and counteracting oppressive noises from airplanes and terminals that have become inevitable in contemporary life, irrespective of its value and/or harm.

Beyond aural tendencies, the exhibition reaches further by considering scale and movement. The sheer volume of Capsule (2019) by Nick Ferguson is an imposing presence in the gallery with a wooden sculpture modelled after the wheel bay of a Boeing 777, floating a few inches off the ground and hovering over visitors. Shown alongside printed images of microscopic substances found in a real plane, it orchestrates a juxtaposition between the enormity of a flying machine and the imperceptible residue it accumulates, revealing traces from the many places it has been including sand, spores, and bacteria.

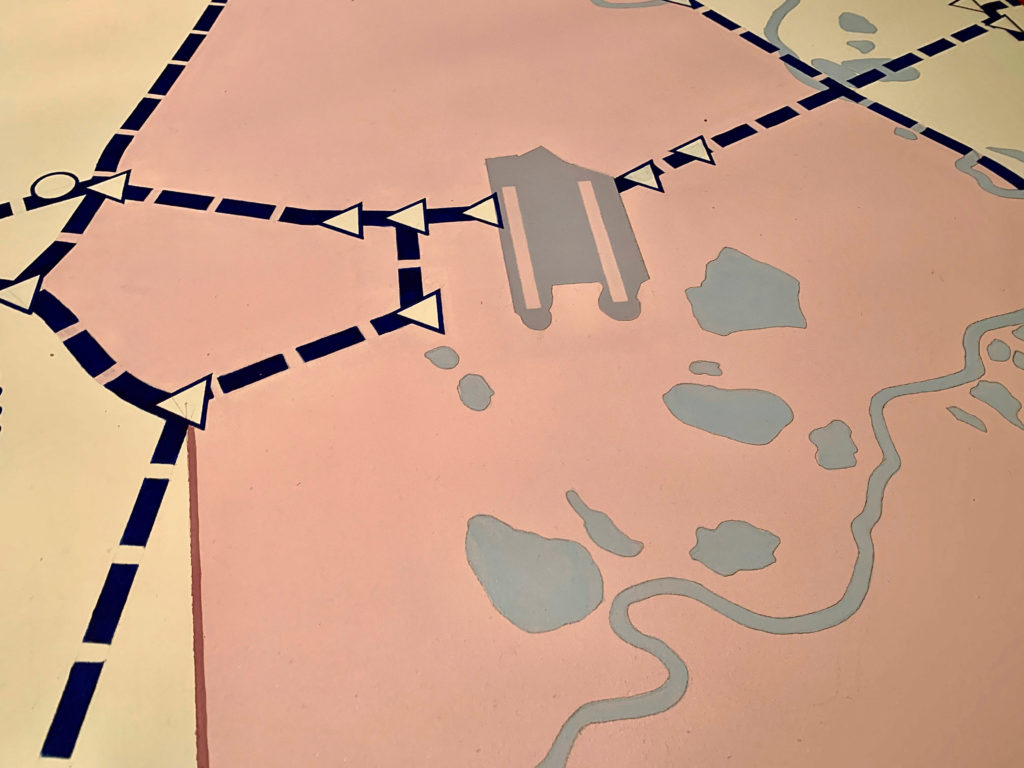

A map nearby, Heathrow (Volumetric Airspace Structures) (2019) by Matthew Flintham, takes the viewer back to west London with a bird’s eye view of the airport complex. Presented on a table that might be used for urban planning, military operation, or board games, it illustrates the topography of the area highlighting a vast infrastructure beneath large sections of controlled airspace, seemingly encroaching on everything else which becomes almost invisible or insignificant.

Navigating the show functions as an exercise of remembrance in many ways, bringing to mind a number of issues that have been at the forefront of public discourse in recent years: from the role of aviation on climate change, to its impact on local communities and ecosystems around airports. And it comes, as if on cue, at a period of heightened environmental concern, propelled most prominently by the Extinction Rebellion movement and climate activist Greta Thunberg, ringing the alarm on the perils of flying.

The controversial Heathrow Airport Expansion also comes through in this context, caught between government plans for future economic growth, and the ongoing resistance from neighbouring residents with campaigns like Stop Heathrow Expansion, No Third Runway Coalition, and Heathrow Association for the Control of Aircraft Noise.

It conjures up conflicting perspectives that unpack a classic dilemma for a society in flux. On one hand, the flight industry is evidently harmful because of its pollution to the planet and the unfair toll on local hosts. Yet, on the other, it is part of a system that facilitates international trade, freedom of movement, and cultural exchanges, each one increasingly more accessible to broader people beyond a privileged few who will always have it. And while it has serious problems that must be addressed, some of which are rightly pointed out here, a world without it entirely is at risk of descent into tribalism and isolationism.

With so much at stake at this particular time and place, the exhibition feels important for its worthwhile attempt in raising these pertinent questions through art, successfully using Heathrow as a case study for matters that undoubtedly have wider implications.

Like the rumble of a plane and many works in this show, the politics of flying will become inescapable as air travel is projected to almost double in size by 2036, despite recent backlash from flight shaming, the rise of staycation, and a spotlight on frequent flyers. The solutions to its unintended consequences are not as straightforward as it might seem, and will likely require a nuanced approach combining systemic changes, paradigm shifts, technological developments, and personal adjustments, all of which cannot come soon enough.

Air Matters: Learning From Heathrow is at Watermans Arts Centre until 5 January 2020. Curated by Nicholas Ferguson in collaboration with Klio Krajewska. Supported by Arts Council England, Forma, London Borough of Hounslow, Kingston School of Art, and Richmond University.

Featured main image: Kate Carr. Image 11. NF. Ascending Composition 1 (For planes). Mixed media, 2019. Included in Air Matters: Learning from Heathrow. 3 October – 5 January 2019.

Mycorrhizal Meditation is a sound-art work by Fiona MacDonald : Feral Practice, commissioned for the enjoyment of the people of Finsbury Park, as part of the exhibition Are We All Addicts Now?

It is designed to be listened to in the park, but can be listened to anywhere.

Mm is a guided meditation (approx. 15 mins) that choreographs a connective journey through the human body and down into a dynamic under-soil world. The voice of the artist entwines with sound recordings made in wooded places, using ambient and contact microphones, and techniques that convert electrical signals in plants and fungi into sound.

Feral Practice complicates a notion of nature as ‘ultimate digital detox’, and guides the user towards the startling interconnectivity of beyond-human nature, the ‘wood-wide-web’ that predates our digital connectivity by millennia. The mycorrhizal network is made up of fungi and plant tissue, and acts both as a woodland’s food store and communication centre.

Mm is suitable for ages 8 years and above.

It can be listened to alone or in a group.

Please tweet @feralpractice @furtherfield #addictsnow to share your experience of the meditation.

12 Remixes, by Michael Szpakowski

From August 2011 to July 2012, the video artist and musician Michael Szpakowski entered a remix competition every month, and compiled his remixes (some of them with accompanying videos) on his website. “I’m 54 years old,” he explained at the beginning of the project, “and although I’m musically reasonably deft I know little about the culture in which I’m attempting to intervene. I know none of the specialised vocabulary, can’t distinguish genres and although I understand what is being said, just about, I don’t speak the language in which posts or comments on this kind of work are framed.” The project, in other words, was a deliberate step outside his “comfort zone”.

The results are often startling. It’s worth comparing the remixes with the original tracks from which they derive, because it provides some insight into Szpakowski’s working methods, and makes you realise the extent of some of the transformations he has achieved.

One of the most striking examples is the remix of “Sandwiches” by the Detroit Grand Pubahs. The original track is a grotesquely overstated hyper-lecherous rap. A synthesised-drum-and-bass arrangement underpins a chipmunk-style speeded-up vocal, warbling lyrics of such obvious symbolism that they hardly qualify as suggestive: “I know you wanna do it/You know I wanna do it too/Out here on the danceflo’/We can make sandwiches…/You can be the bun/And I’ll be the burger, girl…/Make your thighs like butter: easily spread…” The effect is quirky, irritating and compulsive; tongue-in-cheek, deliberately outrageous, blatantly sexist and borderline pervy all at the same time.

Szpakowski’s remix has an entirely different feel. The vocals have been slowed right down from warbly chipmunk to entombed Darth Vader; correspondingly, the bassline has slowed too, from a prefabricated booty-shaker to something subterranean and slightly menacing; and in the space above there are echoey keyboard-notes floating and pulsing like luminous jellyfish. The effect of the lyrics is no longer leeringly voracious, but mournful, obsessive and introspective. There is an instrumental coda with a vaguely Scottish Highlands flavour to it. The feel of the track has changed completely, and so have its texture and geometry. We find ourselves in a darker, much larger space.

Another good example is “OK good stand clear”, based on “110%” by Laura Vane and the Vipertones. The original song is efficient, well-assembled funk/soul, complete with a punchy horn section and a sassy female lead vocal. It’s slick, sharp and professional, but hard-working rather than inspired. Szpakowski’s remix dispenses with almost everything except the rhythm section, which is slowed down slightly to give it more depth and a thumping creaky quality like an elephant in new walking-boots. To this he adds a sampled American voice saying “OK? Good” and “Stand clear of the closing doors!”, and a hammering piano-figure. Again the effect is to open the track out, to give it a more three-dimensional feel, and also to make it much less derivative, much less obviously the product of a particular genre.

In almost every instance Szpakowski’s remixes have a more resonant and spacious feel than the originals; the sounds are dirtier, fuzzier, more textured; and the rhythms are more complex. These changes may not always be entirely to his advantage. As he admits himself, “I don’t dance (or haven’t for twenty years or so), which actually makes a big difference in how one experiences popular music…” Certainly there is one track – a remix of “Paradisco” by Charlotte Gainsbourg and Beck – where Szpakowski’s version has a spiky, angular, echoey jazz feel, but loses out to the original in terms of finger-clicking compulsiveness. It’s true that his remix puts a stronger focus on Gainsbourg’s voice and lyrics than does the original; but whereas Gainsbourg and Beck’s version stays within the disco format and gives it an iconoclastic indie makeover, Szpakowski’s remix takes us beyond that format altogether, and comments on it from the outside.

In some of the tracks there is a move from the USA to Europe in terms of feel. One example is the remix of “What happens in Vegas” by Chuckie ft. Gregor Salto – a histrionic slab of USA club music. Szpakowki’s version (“Shit happens in Vegas”) has a distinctly Kraftwerk-esque, European-techno slant. Also, because the remixes are often crackly, fizzy and hissy, they tend to feel “older” than the originals. At times we seem to be listening to badly-tuned radios in the pre-digital era, or to vinyl LPs smothered in dirt and played through a fluff-laden needle. But this “distressed finish” effect is in keeping with a broader sense that Szpakowki’s remixing technique involves a kind of deconstruction or breaking-apart of the tracks on which he is working. They become less smooth and shiny, less self-contained. The original tracks are often tightly-focussed in terms of their musical styles, with a narrow range of subject-matter, and often with manipulative designs on the audience – wanting to make them feel like dancing, wanting to make them feel sexed-up, or trying to tug at their heart-strings (“Try to Stay Awake” by Frank Friend, “Trojans” by Atlas Genius and “Jigsaw” by Mimi Page are all relationship-based heartstring-tuggers). The remixes, on the other hand, aren’t looking for such straightforward reactions. Their subject-matter is less easy to pin down, and their ingredients bespeak a mixing-together of disparate materials, different cultures, and even different eras.

Non-musical ingredients are one noteworthy feature. In “OK good stand clear”, the voice saying “Stand clear of the closing doors!” comes, as Szpakowki explains, from “New York subway recorded announcements… grabbed, I think, from YouTube”. He is also fond of introducing a voice intoning random numbers – this occurs in several of the tracks. Usually the voice has a foreign accent, and sometimes the numbers are spoken in a foreign language. These number-sequences, says Szpakowski, come from “the so called ‘numbers stations’ which are believed to have been used by various intelligence agencies… they’re available at the internet archive“.

On “I’m getting a cat” the words come from mashed-up Tweets which have been run through a voice-to-text synthesiser. “I am that I am” borrows its vocal from the painter and sound poet Brion Gysin – a voice-sample which, until it begins to distort, sounds rather like a 1950s announcement on the BBC. “Speaking in Tongues” reverses the vocal on a hectoring soul track by Colonel Red called “Rain a Fall”, so that it ends up sounding as if it’s in some unspecified European or possibly Middle Eastern language. And “Sugar Plum Fairy on the Dancefloor” introduces the chiming melody from Tchaikovsky’s Sugar Plum Fairy into a rap called “Disco Technic” by Stan Smith, to surprisingly good effect. There is a genre-busting transgression of boundaries, a throwing-together of cultures, a jumbling-up of eras, and a deliberate use of incongruous material.

The videos Szpakowski has produced to accompany some of these tracks show similar traits. Again his admission that he doesn’t dance is relevant here, because the starting-point for many music videos – a very tight and emphatic synchronisation of visual effects with the beat of the track – is not a particularly dominant feature in his work. The one which succeeds best in this respect is the video for “OK good stand clear”, which projects text versions of the words onto the screen in big letters precisely as we hear them. There is also a lovely moment in the video for “I’m getting a cat” where, in a bit of old black-and-white footage, some youngsters sitting on chairs on a stage start to sway from side to side, apparently in time to the music.

But synchronisation to the beat isn’t Szpakowski’s priority. “I’m getting a cat” provides a good example of the kind of effect he achieves instead. The synthesised vocal for the track first announces that it’s getting a cat, then starts to ask absurd questions about cats and cat-care – “Does your cat try to style your hair?”; “What is your funniest and yet painful cat story?” – which are gradually infiltrated, first by other subject-matter – “Become a big brand on Facebook!” – then by symbols – “Poundsign poundsign poundsign” – and sequences of numbers. What starts off as funny, ironic and nostalgic develops or breaks down into a kind of digital fragmentation, and eventually into wordlessness. The end of the track is a wistful instrumental coda, embellished with piano and strings. And the video follows much the same path. It starts with old footage from the 1960s White House, in which President Lyndon B Johnson seems to be announcing his intention to get a cat to his slightly-bemused aides. Then there are some outtakes from what seems to be an instructional video in which a troubled youngster is being given helpful advice (presumably cat-care advice) by a reassuring and helpful older man. By the end of the track – the coda – we are watching teenagers playing music, drinking coffee and dancing. Again, humour and irony have been replaced by something more wistful and hard-to-define.

“Found” materials, often quite disparate materials spliced together by digital means, are just as important to the videos as they are to the remixes: they feature archive footage of the Whitehouse; shots of groovy teenagers from the Fifties or Sixties; Japanese Noh theatre; imagery based on Little Red Riding-Hood; square-dancing American kids; old claymation footage of teeth wearing boxing gloves; big black lettering; jumbles of coloured pixels; and images of Las Vegas captured from Google Maps, reconstituted into a long sun-baked backwards drive from the middle of town into the desert. Like the musical tracks they accompany, these videos cull their materials from many disparate places; they are full of little jolts of incongruity, slightly-bizarre juxtapositions; they lead us not only inwards towards the music but outwards towards different cultures and different eras; and they also call our attention to the digital medium itself, the Web on which all these materials are available, and the computer software which slices and splices them.

Perhaps most remix artists are more influenced by the work of their immediate peers than by art theory, art history, or inspiration drawn from other cultures. Not so with Szpakowski. As mentioned before, one of these remixes (“I am that I am”) uses a vocal track from Brion Gysin; and the words “OK good”, from “OK good stand clear”, are sampled from a recorded talk by William Burroughs. Burroughs and Gysin were the first proponents of cut-up and fold-up techniques in literature: Gysin was also an experimental painter and sound artist. This link with the two of them hints at a connection between Szpakowki’s remix style and modernist or post-modernist art. Remix culture itself is closely related to mash-ups, which in turn (whether remix artists are aware of it or not) can trace their ancestry not only to cut-ups and fold-ups but to the collages, bricolage, decalcomania and other mixed-media, mixed-genre experiments of the Modernists: experiments which reflected not only an urge on the part of Modernist artists to break free from received genres and formal conventions, but a feeling that the modern mind did not belong to a single era, a single unified body of belief or a single point of view – instead it contained many disparate perspectives, and ideas or images from many different eras and cultures, all thrown together into a jumble. For the modernists, this jumble was itself both one of the joys and one of the symptoms of modernity.

For modernist and post-modernist artists, formal perfection is often a secondary consideration, compared with the excitement of putting things together in new ways, seeing things from new angles. T S Eliot (in “Tradition and the Individual Talent”) described the mind of the artist as a “medium…in which special, or very varied, feelings are at liberty to enter into new combinations”. He made the same point in “The Metaphysical Poets”: the artist, he argues, “is constantly amalagamating disparate experience”; and modern art is bound to be more complicated than the art of earlier centuries, because modern life itself has become more complicated: “Our civilization comprehends great variety and complexity, and this variety and complexity… must produce various and complex results.” It was also argued, by various theorists, that modern artists found it increasingly difficult to belong wholeheartedly to a particular tradition, or to stick to a particular working method or lexicon of forms, because mass reproduction had made so many different traditions and examples, from so many different eras and cultures, available to them. If these observations were true at the beginning of the twentieth century, they are most certainly true now, at the beginning of the twenty-first, when life is characterised not just by “variety and complexity”, but by information-overload, and when the work of other artists, other eras and other traditions is available not only in museums, libraries, books and prints, but online at the click of a mouse or the blink of a Google query-screen. So one way of understanding Szpakowski’s remixes – his particular take on what a remix ought to be like – is to look at them in the light of modernist, post-modernist and digital-modernist aesthetics.

Another neo-modernist aspect of these remixes is their reluctance to woo the audience. There are moments when the arrangements are slightly unsympathetic to the listener. One example of this is “I’m getting a cat”, where the voice-over stops asking absurd questions about cat-care and starts coming out with fragmentary nonsense about Facebook, number-sequences, and “poundsign poundsign poundsign” instead. The “poundsign poundsign poundsign” sequence, in particular, goes on to a point where a lot of listeners might find themselves wishing it would stop. Similarly, on “I am that I am”, the voice-over, which starts with a sequence of variations on the theme of identity –

I AM THAT I AM

AM I THAT I AM

I THAT AM I AM

THAT I AM I AM

AM THAT I I AM

– soon gets speeded-up and distorted into an incomprehensible babble, and this babble is so loud and frenetic that it’s quite hard to hear the music. Again, some listeners may find themselves wishing that the voice-over would stop.

As already mentioned, the vocal track in “I am that I am” is based on an original piece by Brion Gysin, and Szpakowski has actually cut it down in order to re-use it – so although Szpakowski’s track may seem a little bit tough on the audience, it’s actually quite a bit less demanding than Gysin’s original. But the link with Gysin provides a clue to the aesthetics which are apparent throughout the whole “12 Remixes” project. “I am that I am”, as a text, is based on the idea of reordering a five-word line into all its possible variations, as can be seen from the extract above. As such, it has a mathematical quality. It resembles “ordinary” poetry in the same way that a peal of bells resembles “ordinary” music, and its structure and length are determined, not by any particular ideas about what may sound good to an audience, or what may provoke a certain emotional effect, but by the need to run through all the possible variations of a certain sequence in a certain order.

As a sound-poem the piece progresses in a similar way: Gysin takes his sequence of statements, and gradually adds echo to them and speeds them up until they become a frenzied babbling noise. In other words he performs a set of mechanical distortions on them, and increases or redoubles those distortions until they have reached a logical conclusion. Again, he is not particularly thinking about what will grip, entertain or move his audience: his attention is fixed on the materials, the medium and the process. This is not to say that “I am that I am” does not have any affect. It is delivered in the ringing tones of a self-important orator, and when the first layer of echo is added we imagine that the speaker might be addressing a rally in a great hall, like Citizen Kane, Mussolini or Hitler. But the self-assertion of the words is then turned into nonsense as the layers of distortion pile up. We feel firstly that great leaders and orators and being mocked, and then that identity itself is being called into question. But we also feel, as listeners, that these reactions may belong to us at least as much as to the piece itself: it has not been designed primarily with the purpose of producing them, and if we failed to experience them the piece would still have a purpose and meaning of its own beyond them, as a peal of bells has its own purpose and meaning whether we enjoy the sound of it or not.

This concern with sequence and process, with breaking things down into their constituent elements and then reorganising those elements according to mathematical rules, can again be related to the experiments of modernism – to the modernists’ determination to question and rearrange the materials and media from which works of art are made – but as the example of the peal of bells indicates, it can also be linked to much older forms of art; and at the same time it has a particular relevance for artists who are working with computers and code. Five words being reorganised into every possible sequence will produce a flicker of recognition in anyone who has every attempted code-poetry. It’s the kind of experiment which sits very naturally in the digital environment and the new media art genre.

Szpakowski’s remixes cannot be described as mathematical sequences or coded music, but they certainly do show evidence of a Gysin-like interest in variations and logical progressions. This may make them seem a bit unsympathetic in places, but it also gives them a certain air of toughness and detachment. As already mentioned, if they are compared with the original tracks on which they are based, one difference to emerge is that they don’t seem to have such obvious designs on their audience. But it’s also true that they don’t tend to follow such obvious paths in terms of musical development. If we look at “In Paradiscos”, for example, the original track has a very strong feeling of moving up a gear when it comes to the chorus, whereas Szpakowski’s remix doesn’t follow the same pattern. Another example is “the moon is inside the snow”, a remix of “Blindsided” by Luke Leighfield and Jose Vanders (which is itself a cover of an original track by Bon Iver). In Leighfield and Vanders’ version, there is a definite sense of drama and progression, as the female vocal is joined by piano and violin, and then by a male voice singing in harmony. By the end of the song, we feel that we have been taken on an emotional journey. It has a narrative arc. Szpakowski, on the other hand, dispenses with the male harmony altogether, and also with large sections of the song’s lyrics. He cuts up and rearranges snippets of the female vocal to create quite a different impression – more of a Haiku than a romantic poem – and he alternates the original vocal with a second female voice talking in Japanese. The end result is just as beautiful as the track on which it is based, but in a quite different way. It’s more austere and contemplative, less narrative and dramatic. It seems to be less about recounting a personal experience, and more about organising disparate elements into an aesthetically satisfying pattern.

Modernism, cut-up techniques, digital experimentation – perhaps these are big perspectives from which to view what is essentially a fairly modest project. Szpakowski didn’t set out on this series with any particularly grandiose ambitions: he set himself the task of producing one remix a month for a year because he thought it would be something interesting to do: it would build on his strengths as a musician and technophile, but it would also set him a series of new challenges. As it turns out, he has risen to those challenges to great effect and produced something really special – a collection which shows variety of tone and pace, wit and inventiveness, along with unity of design and a distinctive “voice”. Whether it’s a digital-modernist take on remix culture or not, anybody who is interested in experimental music could do a lot worse than put their headphones on and give it a try. It certainly repays close attention.

We are collecting childhood rhymes from around the world spoken by many generations of local residents of the borough for a sound installation as part of the Cultural Olympiad Festival.

Please come to Furtherfield Gallery in Finsbury Park on Saturday 21 July, 11-3pm to take part!

See images of the launch on Flickr.

Artist and composer Michael Szpakowski has worked with local children and their families to create a generative sound sculpture that invokes the collective memory of childhood, drawing on the memories of Haringey residents from all over the world.

A collective memory of childhood will be launched on Saturday 28 July 2012, 2-5pm.

To add your voice to this sound installation come to the gallery on Saturday 21 July between 11am and 3pm. You will meet the artist Michael Szpakowski who will be recording with you and other local residents any childhood rhymes, skipping songs or lullabies.

+ For more information please contact Ale Scapin

Michael Szpakowski is an artist, composer and film-maker who devises and facilitates many of our Outreach projects with young people. Participants create films, games and performances that explore the tools and processes of co-co-creation in a digitally connected world. The work engages young people, meeting them where they are in a constructive, imaginative and inclusive way. With DVcam in hand he finds poetry in the everyday, music in a London pavement and if called upon could find a way to inspire the imaginations of curbstones with his enthusiasm, experience and skill-sharing abilities.

www.somedancersandmusicians.com

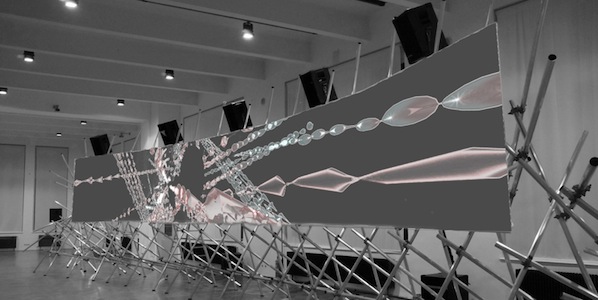

Featured image: Fundamental Forces by Robert Henke and Tarik Barri

In its current state “Fundamental Forces” is a pre-rendered high definition multiple screen projection with surround sound. The visual component is based on Tarik Barri’s ‘Versum’ – a self-programmed computer animation engine. And the auditive component comes from Robert Henke, using MaxMSP, Max4Live and Ableton Live, a software he co-developed. It has been initially commissioned for the RML Cinechamber system which consists of 10 1080p projections and 8 channels of sound (FF00 – FF01). A later version was adapted to work with 5-6 screens and a 5.2 soundsystem. This was used during the sound:frame Festival in Vienna, and it had a highly immersive presence.

When experiencing the work I enjoyed the absence of narrative. Although I noticed some references alluding to concepts based on physics, and basic foundations of the universe. This led me to ask some questions to both artists about their “audiovisual research project”.

Robert Henke is active as composer, AV artist and professor in sound design at the University of Arts in Berlin. As founder and main member of his solo-project “Monolake”, he gained international reputation as one of the leading artists in the field of electronic club music culture. Henke has released more than twenty albums. His performances and installations have been shown and others at the Tate Modern in London, the Centre Pompidou in Paris, the PS1 in New York and the Experimental Media and Performing Arts Center (EMPAC) in Troy. His work “Layering Buddha” received an honorary mention at Ars Electronica in 2007.

Natascha Fuchs: “Fundamental Forces” is presented at sound:frame Festival this year and you worked on it together with Tarik Barri. How your collaboration has started?

Robert Henke: I was looking for Max programmer a few years ago. Tarik replied, but told me that he had no time for that, even if he would like to. However, later he sent me some video stuff he did and I thought that his work could be integrated into Monolake Live. That’s how it all came together.

NF: You call Fundamental Forces ‘an audiovisual research project’. What exactly do you call research? And how much of research involved into your life?

RH: The research part of it is simply the experimentation with the format: what kind of sound can be combined with which of Tarik’s visual ideas and vice versa. We try to find a common language. And since his work does not suggest a common narrative, we also need to come up with our own large scale structures. Where do we start, where do we stop? What kind of timeframes make sense? How can we shape transitions? Questions like this…

NF: You are involved into many different activities.. Is there anything what you like most of all? Music production, performing, visual ideas development, teaching students maybe? What gives you the feeling of ‘life is great and I am satisfied with everything’?

RH: This always changes, but I am most satisfied in moments when my own sense of achievement finds its counterpart in the perception of what I do in public. If I for myself gave a lecture which I felt was really good, and afterwards students come to me and share that notion, – I am happy. If I had a great day in the studio and afterwards play the music to some friends and they like it too, – I am happy. And if things simply do not work out the way I want to, if I have an idea, but every attempt to turn in into sound or visuals does not satisfy me, then I am most frustrated.

NF: You live in Berlin. How does the city and different generations grown up there change together with technology changes? You see many students probably for whom technology is something ready to use now, and it was different at a time when Ableton Live was not yet created..

RH: The biggest transition in general is from a situation that is characterized by a lack of tool in the early 1990s to the total abundance of tools in 2012. The question today is not: how do I do something, but rather: what am I really interested in? All is possible with current technology. Finding your personal language is the biggest challenge these days.

NF: Currently in the interview to Bleep you said that you have so many ideas to explore yourself in the next future. Could you share one of them, what is Robert Henke’s the next?

RH: The biggest project I am working on is a large scale laser and sound installation called ‘Fragile Territories’. It is a challenge in many ways; technically and artistically. I want it to be very good, it is an important work for me, and I still need to do a lot of research. Laser is a very limited media, and in order to create something that is more than a technology demo one needs to invest a lot of time thinking about what exactly to do with it and also find out how to make the best out of the limitations.

Tarik Barri is a Dutch audiovisual composer and software developer. He started programming at the age of seven and has been making electronic music since he was a teenager. After his first official musical releases at the age of twenty one, he quit his studies in biological psychology to pursue the study of music and technology at the Utrecht School of Music and Technology. During this studies he saw how the methods he used to create music could be adapted for the moving image. He programmed his own software to develop new tools for audio-visual performance, composition and data representation.

Natascha Fuchs: You live in the Netherlands, which is famous for successful promoting of media and digital arts/sound. Which Dutch institutions, festivals do you support?

Tarik Barri: I’ve been living in Berlin for a little while now, but definitely living in The Netherlands has been very very good for me to develop my work and my working methods. After I finished school, there was the WWIK, which is a government funding to help new artists develop their work. Also the Netherlands Foundation for Visual Arts, Design and Architecture helped me a lot by giving me a stipend to develop my work. Then there were organisations and festivals like TodaysArt, Sonic Acts and V2 that helped me introduce my work to the general public. Unfortunately many programs are getting cut these days in a new political climate where art in general seems to be regarded a left wing hobby for elitist snobs. Very sad, especially since I don’t agree that ‘art’ in general would be class related or have any specific political color.

NF: You were graduated from Utrecht School of Arts. What exactly did you study there?

TB: Within the Utrecht School of Arts I studied at their School of Music and Technology. And within thát school I graduated in Audio Design. It was the most technical study they had, where I learned about music programming, sound synthesis, acoustics, etc. Especially the programming courses in Max/MSP given by my teacher Marcel Wierckx inspired me to combine music, realtime visuals and programming into one discipline.

NF: What is your participation in collaboration with Monolake?

TB: Within Monolake the roles of Robert Henke and myself are clearly defined: he does the music, I do the visuals. But of course we discuss the visuals and music intensively together and there’s a constant dialog going on between both ourselves as individuals and the works that we produce. This continuous dialog has been of great value for my development in the last couple of years, both artistically and technically.

NF: The artwork which will be presented at sound:frame called ‘audiovisual research project’. What is this continuous research in your life, your aim in it?

TB: Both Robert and I constantly develop our own methods for the creation of music and visuals, and we research the aesthetical results that can be achieved through these methods. Through the combination of sound and visuals, I aim to create a sense of reality. To achieve this I’ve developed software that establishes 3d virtual audiovisual worlds. I then populate these realities with a multitude of objects of various shapes, sizes and other properties. Those objects behave according to laws taken from the real reality. While thus creating a completely new world, with its own sets of objects, elements of what we know can still be recognized within this virtual space. For me this contrast between the new and the known highlights the sense of wonder and possibility that emerges from the space between strict rules and the imagination that tries to defy and transform them. Through a window of strict and rigid laws we enter into infinite, colorful, playful, imaginary worlds.

May / June 2012: Fundamental Forces in Canada, Montreal @ MUTEK Festival

Robert Henke aka Monolake: www.monolake.de

Tarik Barri: www.tarikbarri.nl

sound:frame Festival: www.soundframe.at

(c) Natascha Fuchs is independent expert in cultural projects management and international public relations, graduate of the University of Manchester (Cultural Management) in 2008. She has been living in Vienna, Austria, studying History of Media Arts at the Donau-Universität and collaborating with sound:frame Festival for audio:visual expressions, since her move from Moscow, Russia in 2011. In Russia she was related to MediaArtLab and Media Forum — the special program of the Moscow International Film festival dedicated to media arts, experimental films and digital context with more than 10 years history. As a researcher and practitioner, she works in a variety of topics and participates different international projects focused on media arts, cinema and sound. Columnist and writer for several online magazines.

Featured image: Healing Station. mixed media, interactive installation, size variable. Christy Matson and Jon Brumit, 2009.

The New Materiality: Digital Dialogues at the Boundaries of Contemporary Craft.

March 10–June 12, 2011

Decorative Arts Gallery

http://www.mam.org/exhibitions/details/new-materiality.php

For the first half of the 20th century, curator Fo Wilson reminds us, the practice of craft was heralded as a “remedy” to how human values were changed by the Industrial Age. Here the hand-made was given privileged status over the machine-made, and thus craft forms gifted new value through the artisan. In the latter part of the last century, as the world moved from apprenticeship and artisanship to a more intellectual and theoretical-based framework for valuing contemporary art, so too have craft practices and discourses been challenged. This rethinking of craft has accelerated in the last several years, with books like Glenn Adamson’s Thinking Through Craft and Howard Risatti’s A New Theory of Craft (both 2007), both arguing for conceptual rigor and provocative possibilities within craft as a discipline.

The New Materiality: Digital Dialogues at the Boundaries of Contemporary Craft, an exhibition that began at the Fuller Craft Museum and is currently up at the Milwaukee Art Museum (MAM) until June 12, follows on and extends current trends in contemporary craft. It engages not only with craft’s reinvigoration as a creative practice and discourse, but with how these have been shaped by, and also transformed, new technologies, new designs, new materials and new ideas. Wilson’s exhibition and events make discussions around Art or Craft, Art or Design, Digital or Hand-made, and Conceptual or not seem, in a word, quaint; she engages with a broad set of materialized ideas that divide and relate across the artistry of craft, the ephemera of technology, and the theoretical frames of post-conceptual art.

The exhibition can perhaps best be summarized through the work of the four exhibiting artists/artist teams that spoke at the “Dialogues on Innovation” panel at the Milwaukee Art Museum on April 16th. Collaborative artists Donald Fortescue and Lawrence LaBianca, for example, spoke to Milwaukee activist and printmaker Nicholas Lampert about their piece, Sounding. This work consists of a huge, custom built cabriole-legged table, which was initially filled with beach rocks and sunk to the bottom of the ocean. There it lay, for two months, with a hydrophone to record the ambient sounds of the sea, including the overwhelming swish of waves, the low hum of slow-moving current, and the activity of sea life – the most prominent being the continuous clicks of what must be shrimp in its vicinity. When the artists’ creation reemerged, it brought the bottom of the ocean with it: all the messiness and stink and poetry of the sea – barnacles, rusty parts, plant life, fish scents, mystery and more. It is exhibited with an over sized hornlike funnel, a huge phonograph tied together with zip ties, to amplify the recorded sound.

Sounding, avowedly inspired by Captain Ahab’s hunt for an un-killable whale, acts as a kind of parallel to the ongoing hunt for singular disciplinary focus in craft. The piece dives into the sea, hits “rock bottom,” and looks as if it barely survived; and on its return, we see that Sounding is far from a singular entity. Yes, it is trashed and torn, but it’s also imbued with literal life, entwined with technical innovation, and rich with stories of its journeys. Like the theories and practices behind the current craft movements, it came back more beautiful, more visceral, more sensory, and more technological than it ever was: a new materiality.

You can listen to or download Sounding file here:

http://www.furtherfield.org/audio/Soundings-1.mp3

My discussion with artist Christy Matson revealed an exploratory practice that shifts between digital and hand-made, generative and interactive, and always with an eye towards the implications of each. Soundw(e)ave, her piece on show, is a self-referential textile, where the actual sounds of computerized Jacquard looms were used to create woven compositions. Her noisy sound waves were turned into three patterned pieces of fabric, made by hand-operated, computer-assisted and fully automated (Jacquard) looms, respectively – each weave growing progressively denser with the more advanced technologies used in their production. The piece, says Matson, was a huge turning point in her practice; it pointed her towards a kind of digital craftsmanship, where she was better able to place value on the ideas, materials and skillfulness needed to be an artisan across contemporary digital, craft and art domains.

Soundw(e)ave, generative weaves, triptych (each 34″ x 54″). Christy Matson, 2004.

For example, Matson then began weaving copper wire directly into her fabrics, and, using the magnetic waves our interactions generate and alter, engendered new aural compositions. In other words, her sonic sculpture turns cloth into a Theremin, where movement and hand-waving at the gallery are transformed into the kinds of musical gestures often associated with science-fiction films of the seventies. While Matson’s earlier, sound-generated works were generative and performative on some level, here she moves into real-time interaction, invoking our embodied relations to textiles, craft, technology and language, all in one fell swoop.

healing station, a collaboration with Jon Brumit and quite possibly the most complex of Matson’s installations thus far, sees piezo sensors placed inside of swaths of fabric to pick up the ambient sounds of the room – including gallery-goers, passersby, street sounds, and the minute vibrations in the fabric itself. This lovely noise is then fed back into the space with bass shakers: speakers optimized for sending waves into solid media rather than air. Viewers can literally feel the low hum of presence, absence and movement as the textile, bodies and room speak at and to one another in a perpetual feedback loop of embodied music. The small crowd at the MAM laughed along with Matson when she relayed a story in which her wired-up piece, and its feedback, caused a small fire at one of its showings – quite a performance, indeed.

Tim Tate artfully explained to Milwaukee staple Tom Bamberger that nowadays “craft” is a starting point rather than an end point. I’m paraphrasing here, but he treats craft as an approach, a space of understanding materials, what they’re good at, perhaps their “habits,” and most certainly their implications. Here, narrative, function and the conceptual are always already implicated across technique – whether new or old – and value is derived from a contextual corpus.

Tate’s work is itself a beautifully resolved hodgepodge of hand-blown glass, hi-tech LCD screens, and visceral videos of typewriters and books, all literally tied together with plastic (zip ties again – don’t knock it ‘til you try it!) around a printed circuit board. In Virtual Novelist, for example, miniature monitors display the aforementioned “dead media” tools from behind artefactual casings of glass. Atop are beguiling sculptural homages to each of the gone-but-not-forgotten analog recording devices of yesteryear.

Bamberger is a smart artist with a quick wit, and Tate is similarly not one to spar with unless you have a good grasp of the discourses at hand. In this lively thirty-minute discussion, the two managed to disarm the Art vs Craft debate as both unproductive and long-since over, and open up possibilities for “ornamental aesthetics” in time-based media. Here the implication was that, following Tate’s lead, video objects and installations could place more emphasis on the object and installation – rather than the video – and use each as an equal material that informs and plays off of the other; the video and screen need not be the central focus.

Sonya Clark then told us how she views her practice as a fiber artist as similar to how author Toni Morrison views her own writing practices. In one of her essays (found in several publications, including a collection entitled What Moves at the Margin), the latter tells a story of the Mississippi River, which was laboriously straightened for travel and transport by boat. Every so often, the river floods; but, Morrison goes on, it’s not really flooding. It is remembering. The water is trying to get to where it belongs, to re-member, to embody again. Morrison says writers do the same with their texts; and Clark claims that she remembers through her materials. Originally trained as a fiber artist and now working across found objects, digital art and more, Clark’s practice sees her reclaiming forgotten histories, and giving them greater potency through her processes and media.

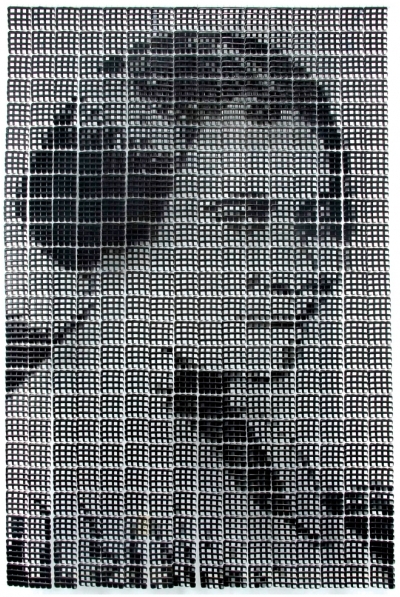

Clark discussed this approach with longtime friend and former colleague, UW-Madison Professor Henry J. Drewal – one of the foremost thinkers surrounding African Art. Clark’s brilliant work on the exhibition, a portrait of Madam CJ Walker, is constructed entirely out of small, acrylic and thin toothed, black hair combs. She overlays the combs and removes some of their teeth to make a huge, grayscale, and literally bit-mapped image.

Madam Walker, the first ever female millionaire in America (and African American to boot), made her fortune selling beauty products to black women hoping to straighten their hair – as was the fashion of the time. And so Clark utilizes her combs, with their own memory, narrative and political weight, to construct a lo-resolution digital image. This exceptional work manages to explicitly straddle issues of race, gender, class, memory and materiality on its very tactile surface, and implicitly engage with the contemporary conceptual frames of digital art and data, in its transcoding of the image from one form to another, and craft, in the final material and hand-made form it takes.

Clark finished with the generous idea that, at present, all art work is collaborative in that it fits into broad social and cultural contexts, builds on extant technologies, and is produced, received, and engaged with outside of the individual’s studio. And Drewal concluded by declaring that technology has always been at center of the arts in the form of new techniques. When something comes into the world, he went on, whether technical or formal or as an image, artists take it someplace else. They “turn common objects… into uncommon things, stretching our imagination and the world” along with them.

These are just a handful of the works in The New Materiality, by four of the artists represented in our discussions – not even all the works they contributed, much less those of the other artists, which include Brian Boldon, Shaun Bullens, Lia Cook, E.G. Crichton, Maaike Evers, Wendy Maruyama, Cat Mazza, Nathalie Miebach, Mike Simonian, Susan Working, and Mark Zirpel.

It is a show that, in its entirety, succeeds in stretching our imagination, through its expansion of craft, art and digital forms, and what they individually and collectively mean today.

Nathaniel Stern (USA / South Africa) is an experimental installation and video artist, net.artist, printmaker and writer. He has produced and collaborated on projects ranging from interactive and immersive environments, mixed reality art and multimedia physical theatre performances, to digital and traditional printmaking, concrete sculpture and slam poetry http://nathanielstern.com.

‘Made Real’, an exhibition by Scott Kildall and Nathaniel Stern, the founders of Wikipedia Art. Can be seen at Furtherfield’s Gallery from 27th May 2011 http://www.furtherfield.org/exhibition/made-real