Join us for the workshop that is also a game where we use roleplay to explore how personal and collective data practices and devices might shape the attitudes and fortunes of a society?

Sign up by 12th August 2020

Participants will each receive one of two devices in the post, and will be given different roles to play as delegates in a fictional trade negotiation. In this first meeting on record, and with minimal knowledge of each other’s cultures, the people of Ourland and New Bluestead must use their devices to communicate with each other and to agree to the terms of a technology and data-culture exchange.

What do they have to offer? How will they decide what they want and what is in their best interests?

What freedoms might they sacrifice, what insights might they gain?

How might they adapt a foreign technology to their own needs, and how might they understand the risks involved?

This is an invitation to participate in Transcultural Data Pact, a research event that is also a game of serious make believe. We welcome you to a future-historic event and clash of data-cultures.

The event will take place online in Zoom and will last for about 3 hours with a lunchtime pre-event orientation session that will last for an hour.

There are two sessions available for both the game event and the pre-event orientation (which is a requirement of participation):

Lunchtime pre-game orientation events

13.30 – 14.30 BST Tues 18 August 2020

13.30 – 14.30 BST Wed 19 August 2020

Transcultural Data Pact Game events

13.15 – 16.30 BST Thurs 20 August 2020

13.15 – 16.30 BST Fri 21 August 2020

In exchange for your time you will exercise your creative agency contributing to the ideation of future technologies for live personal data. You might even discover new meanings in your personal data in places you never thought of looking before!

All participants will receive a £20 voucher for their contribution to the research.

This is an open invitation to all. No experience in role-playing games is necessary.

Pregame orientation events

13.30 – 14.30 to learn about your devices and about LARPing, to introduce and develop the scenarios, to build the fictional worlds together.

Game Event Schedule

13.20 – 13.30 Arrive in Zoom and sign in

13.30 Introduction

13.40 – 16.00 Nations Technology Exchange Live Action Role Play

16.00 – 16.30 Debrief, reflection and survey

For any enquiries, please email ruth.catlow@furtherfield.org

Findings contribute to a research paper Human-Computer Interaction (CHI).

The Transcultural Data Pact is a Qualified Selves research event that uses data objects to stretch people’s imagination about the collection and usage of their own data to investigate personal and collective data devices and practices that add real value.

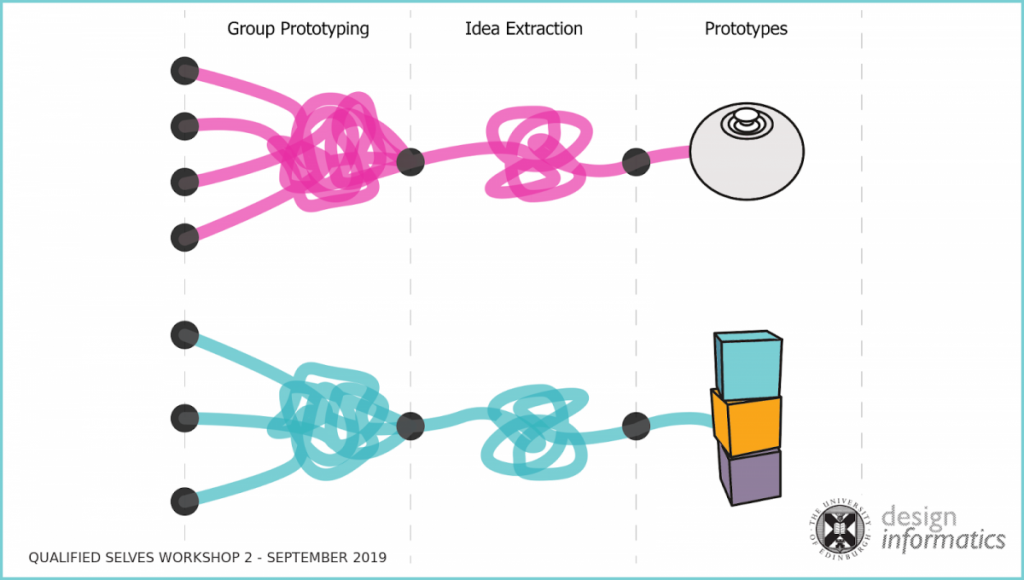

Qualified Selves is a joint project between Lancaster and Edinburgh Universities. Improving how individuals make sense of data management (from social media to activity trackers to home IoT devices) in order to enhance personal decision making, increase productivity, and improve their quality of life. Its novel approach to co-design and co-creation has supported the development of new prototypes to help think about tracking data in different ways. https://sensemake.org/

Transcultural Data Pact is created by Ruth Catlow (Furtherfield/DECAL) with Dr Kruakae Pothong, Billy Dixon, Dr Evan Morgan and Prof. Chris Speed from Edinburgh University, in collaboration with Kate Genevieve.

Ruth Catlow is Director of DECAL. Furtherfield is London’s first (de)centre for digital arts. DECAL is a Furtherfield initiative which exists to mobilise research and development by leading artists, using blockchain and web 3.0 technologies for fairer, more dynamic and connected cultural ecologies and economies.

On June the 16th Tatiana Bazzichelli and Lieke Ploeger presented a new Disruption Network Lab conference entitled “AI TRAPS” to scrutinize Artificial Intelligence and automatic discrimination. The conference touched several topics from biometric surveillance to diversity in data, giving a closer look at how AI and algorithms reinforce prejudices and biases of its human creators and societies, to find solutions and countermeasures.

A focus on facial recognition technologies opened the first panel “THE TRACKED & THE INVISIBLE: From Biometric Surveillance to Diversity in Data Science” discussing how massive sets of images have been used by academic, commercial, defence and intelligence agencies around the world for their research and development. The artist and researcher Adam Harvey addressed this tech as the focal point of an emerging authoritarian logic, based on probabilistic determinations and the assumption that identities are static and reality is made through absolute norms. The artist considered two recent reports about the UK and China showing how this technology is yet unreliable and dangerous. According to data released under the UK´s Freedom of Information Law, 98% of “matches” made by the English Met police using facial recognition were mistakes. Meanwhile, over 200 million cameras are active in China and – although only 15% are supposed to be technically implemented for effective face recognition – Chinese authorities are deploying a new system of this tech to racial profile, track and control the Uighurs Muslim minority.

Big companies like Google and Facebook hold a collection of billions of images, most of which are available inside search engines (63%), on Flickr (25%) and on IMdB (11 %). Biometric companies around the world are implementing facial recognition algorithms on the pictures of common people, collected in unsuspected places like dating-apps and social media, to be used for private profit purposes and governmental mass-surveillance. They end up mostly in China (37%), US (34%), UK (21%) and Australia (4%), as Harvey reported.

Metis Senior Data Scientist Sophie Searcy, technical expert who has also extensively researched on the subject of diversity in tech, contributed to the discussion on such a crucial issue underlying the design and implementation of AI, enforcing the description of a technology that tends to be defective, unable to contextualise and consider the complexity of the reality it interacts with. This generates a lot of false predictions and mistakes. To maximise their results and reduce mistakes tech companies and research institutions that develop algorithms for AI use the Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) technique. This enables to pick a few samples selected randomly from a dataset instead of analysing the whole of it for each iteration, saving a considerable amount of time. As Searcy explained during the talk with the panel moderator, Adriana Groh, this technique needs huge amount of data and tech companies are therefore becoming increasingly hungry for them.

In order to have a closer look at the relation between governments and AI-tech, the researcher and writer Crofton Black presented the study conducted with Cansu Safak at The Bureau of Investigative Journalism on the UK government’s use of big data. They used publicly available data to build a picture of companies, services and projects in the area of AI and machine learning, to map what IT systems the British government has been buying. To do so they interviewed experts and academics, analysed official transparency data and scraped governmental websites. Transparency and accountability over the way in which public money is spent are a requirement for public administrations and they relied on this principle, filing dozens of requests under the Freedom of Information Act to public authorities to get audit trails. Thus they mapped an ecosystem of the corporate nexus between UK public sector and corporate entities. More than 1,800 IT companies, from big ones like BEA System and IBM to small ones within a constellation of start-ups.

As Black explained in the talk with the moderator of the keynote Daniel Eriksson, Transparency International Head of Technology, this investigation faced systemic problems with disclosure from authorities, that do not keep transparent and accessible records. Indeed just 25% of the UK-government departments provided some form of info. Therefore details of the assignments are still unknown, but it is at least possible to list the services those companies deploying AI and machine learning can offer governments: connect data and identify links between people, objects, locations; set up automated alerts in the context of border and immigration control, spotting out changes in data and events of interest; work on passports application programs, implementing the risk-based approaches to passports application assessments; work on identity verification services using smartphones, gathering real time biometric authentications. These are just few examples.

Maya Indira Ganesh opened the panel “AI FOR THE PEOPLE: AI Bias, Ethics & the Common Good” questioning how tech and research have historically been almost always developed and conducted on prejudiced parameters, falsifying results and distorting reality. For instance, data about women’s heart attacks hadn´t been taken in consideration for decades, until doctors and scientists determined that ECG-machines calibrated on the data collected from early ´60s could neither predict heart attacks in women, nor give reliable data for therapeutic purposes, because they were trained only on male population. Just from 2007 ECG-machines were recalibrated on parameters based on data collected from female individuals. It is not possible to calculate the impact this gender inequality had on the development of modern cardiovascular medicine and on the lives of millions of women.

As the issue of algorithmic bias in tech and specifically in AI grows, all big tech firms and research institutions are writing ethics charters and establishing ethics boards sponsoring research in these topics. Detractors often refer to it as ethics-washing, which Ganesh finds a trick to mask ethics and morality as something definable in universal terms or scale: though it cannot be computed by machines, corporations need us to believe that ethics is something measurable. The researcher suggested that in such a way the abstraction and the complexity of the machine get easy to process as ethics becomes the interface used to obfuscate what is going on inside the black box and represent its abstractions. “But these abstractions are us and our way to build relations” she objected.

Ganesh wonders consequently according to what principle it shall be acceptable to train a facial recognition system, basing it on video of transgender people, as it happened in the alarming “Robust transgender face recognition” research, based on data from people undergoing hormone replacement therapy, Youtube videos, diaries and time-lapse documentation of the transition process. The HRT Transgender Dataset used to train AI to recognize transgender people worsens the harassment and the targeting that trans-people already experience daily, targeting and harming them as a group. However, it was partly financed by FBI and US-Army, confirming that law enforcement and national security agencies appear to be very interested in these kinds of datasets and look for private companies and researchers able to provide it.

In this same panel professor of Data Science and Public Policy Slava Jankin reflected on how machine learning can be used for common good in the public sector. As it was objected during the discussion moderated by Nicole Shephard, Researcher on Gender, Technology and Politics of Data, the “common good” isn’t easy to define, and like ethics it is not universally given. It could be identified with those goods that are relevant to guarantee and determine the respect of human rights and their practice. The project that Jankin presented was developed inside the Essex Centre for Data analytics in a synergic effort of developers, researches, universities and local authorities. Together, they tried to build an AI able to predict within reliability where children lacking school readiness are more likely to be found geographically, to support them in their transition and gaining competencies, considering social, economic and environmental conditions.

The first keynote of the conference was the researcher and activist Charlotte Webb, who presented her project Feminist Internet in the talk “WHAT IS A FEMINIST AI?”

<<There is not just one possible internet and there is not just one possible feminism, but only possible feminisms and possible internets>>. Starting from this assumption Webb talked about Feminist Human Computer Interaction, a discipline born to improve understandings about how gender identities and relations shape the design and use of interactive technologies. Her Feminist Internet is a no profit organisation funded to make internet a more equal space for women and other marginalized groups. Its approach combines art, design, critical thinking, creative technology development and feminism, seeking to build more responsible and bias-free AI able to empower people considering the causes of marginalization and discrimination. In her words, a feminist AI is not an algorithm and is not a system built to evangelize about a certain political or ideological cause. It is a tool that aims at recognizing differences without minimizing them for the sake of universality, meeting human needs with the awareness of the entire ecosystem in which it sits.

Tech adapts plastically to pre-existing discriminations and gender stereotypes. In a recent UN report, the ‘female’ obsequiousness and the servility expressed by digital assistants like Alexa, the Google Assistant, are defined as example of gender biases coded into tech products, since they are often projected as young women. They are programmed to be submissive and accept abuses. As stated by Feldman (2016) by encouraging consumers to understand the objects that serve them as women, technologists abet the prejudice by which women are considered objects. With her projects, Webb pushes to create alternatives that educate to shift this systemic problem – rather than complying with market demands – first considering that there is a diversity crisis in the AI sector and in the Silicon Valley. Between 2.5 and 4% of Google, Facebook and Microsoft employees are black, whilst there are no public data on transgender workers within these companies. Moreover, as Webb pointed out, just 22% of the people building AI right now are female, only 18% of authors at major AI-conferences are women, whilst over 80% of AI-professors are men. Considering companies with decisive impact on society women comprise only 15% of AI research staff at Facebook and 10% in Google.

Women, people of colour, minorities, LGBTQ and marginalized groups are substantially not deciding about designing and implementing AI and algorithms. They are excluded from the processes of coding and programming. As a result the work of engineers and designers is not inherently neutral and the automated systems that they build reflect their perspectives, preferences, priorities and eventually their bias.

Washington Tech Policy Advisor Mutale Nkonde focused on this issue in her keynote “RACIAL DISCRIMINATION IN THE AGE OF AI.” She opened her dissertation reporting that Google´s facial intelligence team is composed by 893 people, and just one is a black woman, an intern. Questions, answers and predictions in their technological work will always reflect a political and socioeconomic point of view, consciously or unconsciously. A lot of the tech-people confronted with this wide-ranging problem seem to undermine it, showing colour-blindness tendencies about what impacts their tech have on minorities and specifically black people. Historically credit scores are correlated with racist segregated neighbourhoods and risk analyses and predictive policing data are corrupted by racist prejudice, leading to biased data collection reinforcing privileges. Without a conscious effort to address racism in technology, new technologies will replicate old divisions and conflicts. By instituting policies like facial recognition we just replicate rooted behaviours based on racial lines and gender stereotypes mediated by algorithms. Nkonde warns that civil liberties need an update for the era of AI, advancing racial literacy in Tech.

In a talk with the moderator, the writer Rhianna Ilube, the keynote Nkonde recalled that in New York´s poor and black neighbourhood with historically high crime and violence rates, Brownsville, a private landlord in social housing wanted to exchange keys for facial recognition software, so that either people accept surveillance, or they lose their homes. The finding echoes wider concerns about the lack of awareness of racism. Nkonde thinks that white people must be able to cope with the inconvenience of talking about race, with the countervailing pressures and their lack of cultural preparation, or simply the risk to get it wrong. Acting ethically isn´t easy if you do not work on it and many big tech companies just like to crow about their diversity and inclusion efforts, disclosing diversity goals and offering courses that reduce bias. However, there is a high level of racial discrimination in tech sector and specifically in the Silicon Valley, at best colour-blindness – said Nkonde – since many believe that racial classification does not limit a person’s opportunities within the society, ignoring that there are instead economic and social obstacles that prevent full individual development and participation, limiting freedom and equality, excluding marginalized and disadvantaged groups from the political, economic, and social organization. Nkonde concluded her keynote stressing that we need to empower minorities, providing tools that allow overcoming autonomously socio-economic obstacles, to fully participate in society. It is about sharing power, taking in consideration the unconscious biases of people, for example starting from those designing the technology.

The closing panel “ON THE POLITICS OF AI: Fighting Injustice & Automatic Supremacism” discussed the effect of a tool shown to be not neutral, but just the product of the prevailing social economical model.

Dia Kayyali, Leader of the Tech and Advocacy program at WITNESS, described how AI is facilitating white supremacy, nationalism, racism and transphobia, recalling the dramatic case of the Rohingya persecution in Myanmar and the oppressive Chinese social score and surveillance systems. Pointing out critical aspects the researcher reported the case of the Youtube anti-extremism-algorithm, which removed thousands of videos documenting atrocities in Syria in an effort to purge hate speech and propaganda from its platform. The algorithm was trained to automatically flag and eliminate content that potentially breached its guidelines and ended up cancelling documents relevant to prosecute war crimes. Once again, the absence of the ability to contextualize leads to severe risks in the way machines operate and make decisions. Likewise, applying general parameters without considering specificities and the complex concept of identity, Facebook imposed in 2015 new policies and arbitrarily exposed drag queens, trans people and other users at risk, who were not using their legal names for safety and privacy reasons, including domestic violence and stalking.

Researcher on gender, tech and (counter) power Os Keyes considered that AI is not the problem, but the symptom. The problem are the structures creating AI. We live in an environment where few highly wealthy people and companies are ruling all. We have bias in AI and tech because their development is driven by exactly those same individuals. To fix AI we have to change requirements and expectations around it; we can fight to have AI based on explainability and transparency, but eventually if we strive to fix AI and do not look at the wider picture, in 10 years the same debate over another technology will arise. Keyes considered that since its very beginning AI-tech was discriminatory, racialized and gendered, because society is capitalist, racist, homo-transphobic and misogynistic. The question to pose is how we start building spaces that are prefigurative and constructed on values that we want a wider society to embrace.

As the funder and curator of the Disruption Network Lab Tatiana Bazzichelli pointed out during the moderation of this panel, the problem of bias in algorithms is related to several major “bias traps” that algorithm-based prediction systems fail to win. The fact that AI is political – not just because of the question of what is to be done with it, but because of the political tendencies of the technology itself – is the real aspect to discuss.

In his analysis of the political effects of AI, Dan McQuillan, Lecturer in Creative and Social Computing from the London University, underlined that while the reform of AI is endlessly discussed, there seems to be no attempt to seriously question whether we should be using it at all. We need to think collectively about ways out, learning from and with each other rather than relying on machine learning. Countering thoughtlessness of AI with practices of solidarity, self-management and collective care is what he suggests because bringing the perspective of marginalised groups at the core of AI practice, it is possible to build a new society within the old, based on social autonomy.

What McQuillan calls the AI realism appears to be close to the far-right perspective, as it trivialises complexity and naturalises inequalities. The character of learning through AI implicates indeed reductive simplifications, and simplifying social problems to matters of exclusion is the politics of populist and Fascist right. McQuillan suggests taking some guidance from the feminist and decolonial technology studies that have cast doubt on our ideas about objectivity and neutrality. An antifascist AI, he explains, shall involve some kinds of people’s councils, to put the perspective of marginalised groups at the core of AI practice and to transform machine learning into a form of critical pedagogy.

Pic 7: Dia Kayyali, Os Keyes, Dan McQuillan and Tatiana Bazzichelli during the panel “ON THE POLITICS OF AI: Fighting Injustice & Automatic Supremacism”

We see increasing investment on AI, machine learning and robots. Automated decision-making informed by algorithms is already a predominant reality, whose range of applications has broadened to almost all aspects of life. Current ethical debates about the consequences of automation focus on the rights of individuals and marginalized groups. However, algorithmic processes generate a collective impact too, that can only be addressed partially at the level of individual rights, as it is the result of a collective cultural legacy. A society that is soaked in racial and sexual discriminations will replicate them inside technology.

Moreover, when referring to surveillance technology and face recognition software, existing ethical and legal criteria appear to be ineffective and a lack of standards around their use and sharing just benefit its intrusive and discriminatory nature.

Whilst building alternatives we need to consider inclusion and diversity: If more brown and black people would be involved in the building and making of these systems, there would be less bias. But this is not enough. Automated systems are mostly trying to identify and predict risk, and risk is defined according to cultural parameters that reflect the historical, social and political milieu, to give answers able to fit a certain point of view and make decisions. What we are and where we are as a collective, what we have achieved and what we still lack culturally is what is put in software to make those same decisions in the future. In such a context a diverse team within a discriminatory conflictual society might find ways to flash the problem of bias away, but it will get somewhere else.

The truth is that automated discrimination, racism and sexism are integrated in tech-infrastructures. New generation of start-ups are fulfilling authoritarian needs, commercialising AI-technologies, automating biases based on skin colour and ethnicity, sexual orientation and identity. They develop censored search engine and platforms for authoritarian governments and dictators, refine high-tech military weapons training them using facial recognition on millions of people without their knowledge. Governments and corporations are developing technology in ways that threaten civil liberties and human rights. It is not hard to imagine the impact of the implementation of tools for robotic gender recognition, within countries were non-white, non-male and non-binary individuals are discriminated. Bathrooms and changing rooms that open just by AI gender-detection, or cars that start the engine just if a man is driving, are to be expected. Those not gender conforming, who do not fit traditional gender structures, will end up being systematically blocked and discriminated.

Open source, transparency and diversity alone will not defeat colour-blinded attitudes, reactionary backlashes, monopolies, other-directed homologation and cultural oppression by design. As it was discussed in the conference, using algorithms to label people based on sexual identity or ethnicity has become easy and common. If you build a technology able to catalogue people by ethnicity or sexual identity, someone will exploit it to repress genders or ethnicities, China shows.

In this sense, no better facial recognition is possible, no mass-surveillance tech is safe and attempts at building good tech will continue to fail. To tackle bias, discrimination and harm in AI we have to integrate research on and development of technology with all of the humanities and social sciences, deciding to consciously create a society where everybody could participate to the organisation of our common future.

Curated by Tatiana Bazzichelli and developed in cooperation with Transparency International, this Disruption Network Lab-conference was the second of the 2019 series The Art of Exposing Injustice.

More info, all its speakers and thematic could be found here: https://www.disruptionlab.org/ai-traps

The videos of the conference are on Youtube and the Disruption Network Lab is also on Twitter and Facebook.

To follow the Disruption Network Lab sign up for its Newsletter and get informed about its conferences, ongoing researches and projects. The next Disruption Network Lab event “Citizen of evidence” is planned for September 20-21 in Kunstquartier Bethanien Berlin. Make sure you don´t miss it!

Photocredits: Maria Silvano for Disruption Network Lab

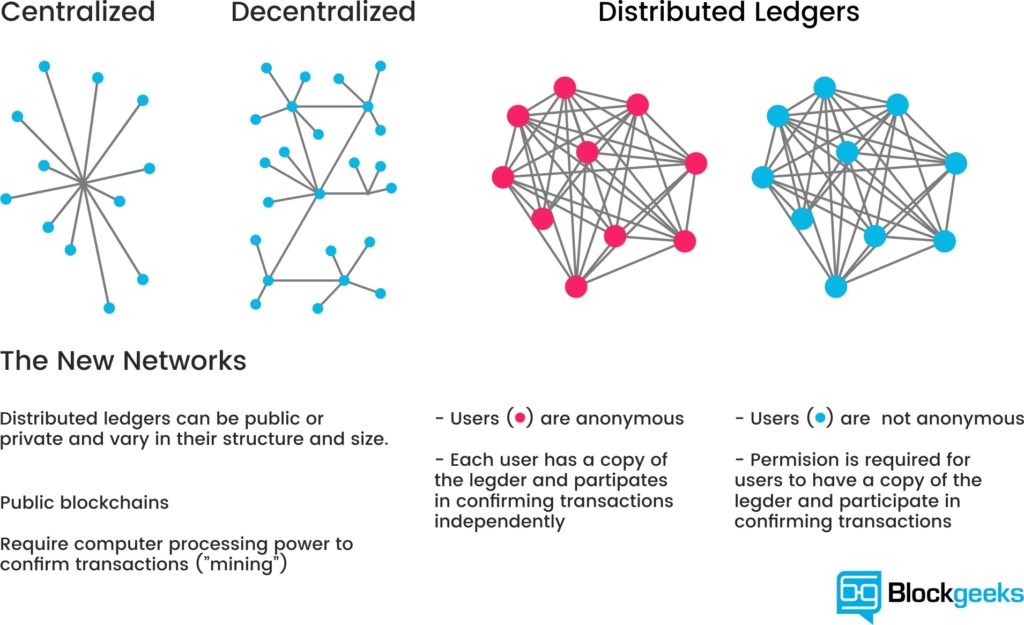

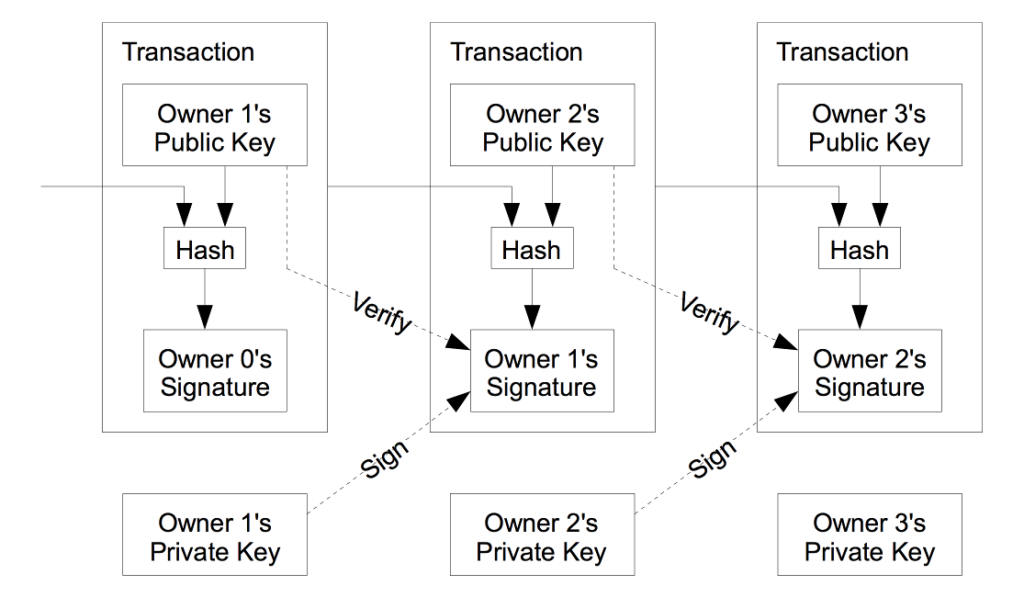

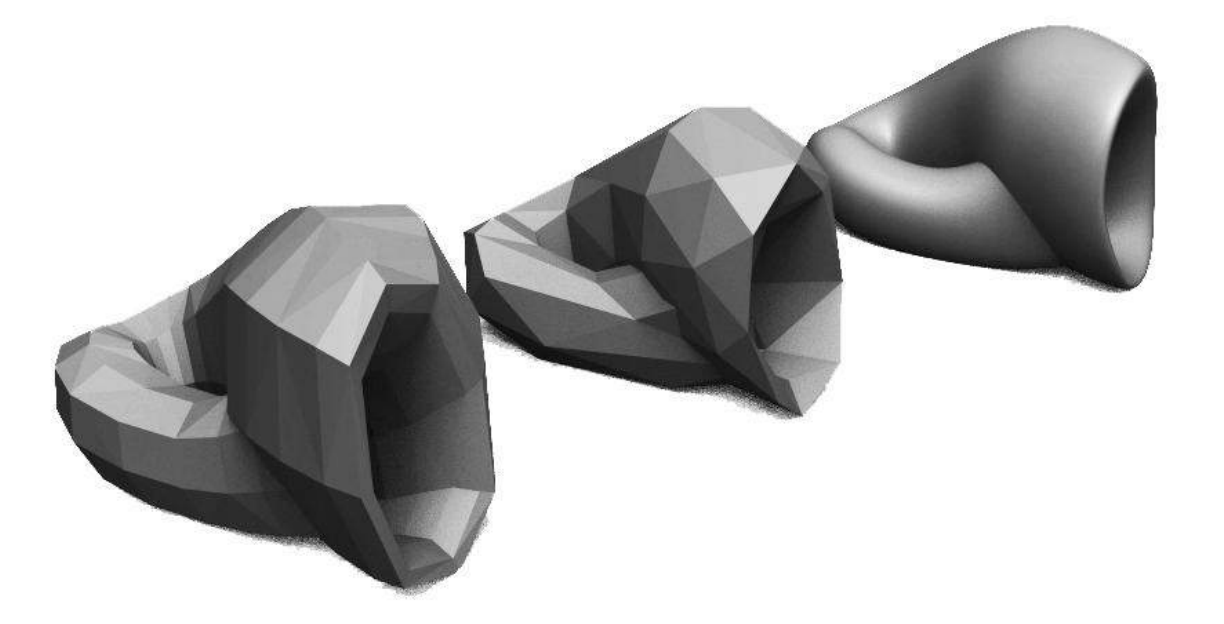

Data structures hold information in a way that makes it easier to be manipulated by software, given particular constraints on computing resources such as the time or space taken up. A linked list takes very little space in a computer’s memory on top of the space taken up by the data it contains and is very quick to add new data to but it is very slow to search from the beginning to the end of the list.

In contrast, a “hash table” data structure makes looking up information much faster by calculating a unique identifier “hash” for each item that can be used as an index entry for the data rather than having to search all the way through a long list of links. Think of a hash as a very large, very unique number that can be reliably calculated for any piece of data – any file containing the text “Hello world!” will have the same cryptographic hash as any other. The cost of this fast access is that the table must be allocated and configured in full before data can start to be stored in it.

A “binary tree” balances speed and storage space by storing data in a structure that looks like a tree with two branches at the end of each branch, creating a simple hierarchy that takes very little initial extra storage space but that given its structure is relatively fast to search compared to a linked list.

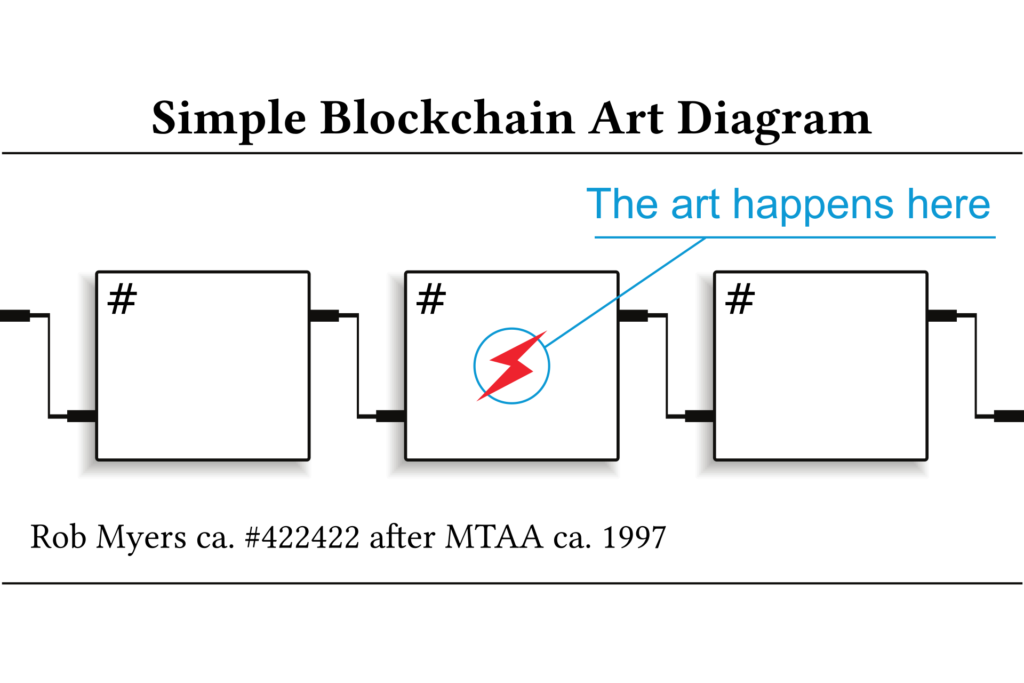

Each block in a blockchain is linked to the previous one by identifying it using its (cryptographic) hash value. And the transactions in the block are stored in a (cryptographic hash) tree. This means that a blockchain is a more complex structure than the simple image at the top of this page. But so what? Why should we care about the shape of the blockchain when its social, environmental and political impact seem to be in such urgent need of critique?

The geometric, techonomic and social form of a blockchain are all related, and understanding one helps us to reason better about the others. As the quick tour through software data structure design above indicates, the constraints on technological form are not abstract, they are tied to real needs and agendas. Bitcoin is no exception to this – the lists and trees that make up its blockchain as they are built and broadcast on a peer-to-peer network by computers competing to claim economic incentives for doing so were chosen very explicitly to exclude the intervention of the state and other “trusted third parties” (such as banks) in authentic economic relationships between peers.

Bitcoin’s algorithms prioritise the security of the blockchain above all else, maximising security like a mythical Artificial Intelligence “paperclipper” maximises the production of a particular material good regardless of the other consequences . This explains Bitcoin’s energy consumption, which whilst lower than the US military or the other equivalent systems that guarantee the security of the dollar is probably still much higher than Satoshi Nakamoto originally envisioned.

There are other algorithms, though, which have been created since 2008 to address perceived flaws in Bitcoin’s design or to address different ideological agendas. These create different forms, and contrast instructively with that of Bitcoin’s blockchain. Please note that these are experimental and often controversial technologies. Nothing that follows is investment advice.

Bitcoin creates blocks on average every ten minutes. Faster currencies quickly emerged, LiteCoin and Dogecoin are leading examples, with 2.5 minute and one minute block times respectively. Blocks may contain more or fewer transactions, and be more or less frequent even within the same blockchain as the algorithms tweak its parameters to ensure its security. Blockchains have rhythm, they stall or race, each block is larger or smaller and closer or further from the last one. Transactions fan into and out from addresses in each block, with varying values of currency or amounts of data each time. We are now very far from the block-and-arrow diagrams of linked lists indeed.

The Ethereum system, which extends Bitcoin’s financial ledger into a more general system for “smart contracts”, has the smallest block time of any leading cryptocurrency – fifteen seconds. Like the others mentioned it still uses a variant of the energy-hungry “Proof of Work” security system from Bitcoin. In Proof of Work, anyone who wants to add a block of transactions to the list must consume computing resources to solve a puzzle (essentially guessing a large number ending with multiple zeroes). As these resources cost money, anyone willing to expend them must stand to gain more from adding the next block than they lose to their electricity bill. This Game Theory gambit secures a Proof of Work blockchain. The mindlessly focussed, paperclipper nature of blockchain security algorithms means that as more people use more computers to compete to be the next person to add a block to the chain and claim the economic reward for doing so, the difficulty and therefore the amount of electricity required to solve that puzzle has increased massively, growing the energy footprint of cryptocurrency.

Ethereum is planning to switch to a “Proof of Stake” system, like that used in currencies like NXT and Decred (about which more below). Rather than burning electricity like Proof of Work, Proof of Stake uses a blockchain’s own existing currency “staked” by users to demonstrate their standing within the system and to thereby get a chance to be chosen by the network to add the next block. Proof of Stake and its related “Proof of Authority” system move from the “miners” of Proof of Work who operate on the blockchain from outside to a system of capitalist investors or even an aristocratic class of gatekeepers who operate within the logic of the blockchain itself. This folds the blockchain’s outside in on itself.

Bitcoin’s blocks have been fixed at one megabyte in size since a temporary security fix by Satoshi Nakamoto introduced the limit. As Bitcoin usage has grown, blocks have become increasingly full (allegedly often as a result of economic “spam” attacks intended to manipulate prices – competing for space in blocks drives up transaction fees which can in turn discourage users and ultimately drive down the price of Bitcoin). How should this problem be addressed – how should Bitcoin scale? Should the number of transactions stored in the blockchain grow, increasing the block size limit and making it harder for individuals to store the blockchain on consumer hardware in a decentralised manner? Or should transactions be somehow moved “off-chain” into “second-tier” systems that build on top of the blockchain, adding complexity and introducing potential new choke-points for existing capital to exploit? Big blocks or small blocks (like the big or little ends of eggs, or integers…)? This is a real debate in the Bitcoin world, and illustrates how the consequences of a simple change in technical form like, for example, increasing block sizes from one to two megabytes, can have profound effects on the social and economic form of a cryptocurrency. “Big blockers” propose solutions like the breakaway “Segwit2X” or “Bitcoin Cash” systems, scaling “on-chain” with ever greater amounts of data in the same structures. “Small blockers” propose solutions that move data out of the blockchain, into “Segregated Witnesses” that store cryptographic signatures outside of the blockchain, or the cybernetic rhizomes of “Lightning Networks”.

A Lightning Network adds a second peer-to-peer network of nodes that pass transactions between themselves. These are all valid Bitcoin transaction data structures, but unlike the main Bitcoin peer-to-peer network they are not immediately broadcast to the main Bitcoin network to be bundled up into blocks. Rather they can be replaced at any moment by new transactions, sending different amounts of cryptocurrency along a “channel” between one or (most often) more participants arranged in a random network like the one used by the Tor privacy network.

It’s an elegant but sometimes complex solution, and one that triggers moral panic within some elements of the Bitcoin community equivalent to that triggered by Bitcoin within some elements outside of it. Lightning Nodes with more Bitcoin can extract more fees from Lightning Network transactions, to be sure, and this is a form of centralisation. Decentralisation’s value to cryptocurrency is as a concrete guarantor of security, and Bitcoin’s value is its security. But individuals can still run Lightning Network nodes and send transactions between each other, and pools of capital already have centralising effects in exchanges and mining cartels.

Techniques similar to those used to move transactions off-chain by Lightning Networks can be used to move value between different blockchains without exchanges centralising the process. “Atomic Swaps”, the “Plasma” system and the realisation of the previously mythical “Doge-Ethereum bridge” using the TrueBit system are all different ways of building wormholes between the separate universes of individual blockchains.

Another approach to scaling is borrowed from conventional database design: breaking the blockchain into smaller and smaller pieces or “shards“, forming another tree structure, allows each group of users of the blockchain to only have to keep track of the part that contains the transactions they are interested in. The Ethereum blockchain will move to sharding in future, after its switch to Proof of Stake. Sharding destroys the metronomic, panopticonic unity of the blockchain to create islands of transactions whose truth is local to them, a non-monotonic logic that makes moving value and information between shards difficult but still not impossible.

CryptoKitties can go on their own shard, the Gnosis prediction market on another one, and if one needs to bet on something kitty-related this will require communicating cross-shard. From islands in the net to islands in the blockchain. Techonomically, the data structures and economic incentives of such a system are more complex than a unified blockchain, but making access to the network cheaper by requiring each user to store less data to send their transactions restores the blockchain’s initial low barrier of entry.

Deciding how to scale is a matter of governance. The Decred cryptocurrency has put governance front and centre. As well as moving to a hybrid Proof of Work / Proof of Stake system it has implemented an “on-chain-governance” system. Decred contains the forum for its own critique and transformation, implemented as an extension of the staking and voting system used by its Proof of Stake system. On-chain governance is controversial but addresses calls to improve the governance of cryptocurrency projects without falling prey to the off-chain voluntarism that can result from a failure to understand how the technomic and social forms of cryptocurrencies relate in finely-tuned balance.

Some post-Bitcoin systems move further away from the form of a chain or do without them altogether. The Holochain system gives each user their own personal blockchain and stores a link to it in a global “Distributed Hash Table” of entries (like that used by the BitTorrent system), a forest of trees rather than a tree of shards. This possibly solves the bandwidth problem of simple blockchain technology but weakens some of their strengths in a trade off of convenience against long-term security and robustness. Iota (the most controversial technical design discussed here) doesn’t have a blockchain at all. It uses a “tangle” of transactions, within which each new transaction must do the Proof of Work of validating several previous transactions. This seems like an ideal restoration of the original vision of Bitcoin as a peer-to-peer currency, solving the problems centralisation and energy usage, but the current Iota network is in fact heavily centralised by its reliance on nodes controlled by the Iota foundation to secure it.

IPFS is not a cryptocurrency and does not use a blockchain but it complements the blockchain technologically and often socially. IPFS is related to blockchain technology in its use of cryptography and the logic of game theory but also as a popular way of storing information that is too large to fit on the blockchain. And in its use of a cryptocurrency token – “Filecoin” – to pay for storage on its main network. Filecoin was released in an “Initial Coin Offering” in 2017, and that is all we will say about ICOs here… IPFS uses a “Merkle DAG”, a network of links similar to the World Wide Web or a filesystem, but with each item (the pages or files) represented not by a human-given name but by the cryptographic hash of its content. “Merkle” refers not to the German Chancellor but to the computer scientist who described this use of cryptographic hashes in a tree data structure (like that used in Bitcoin). “DAG” is an acronym for “Directed Acyclic Graph” – a network with no loops in it because loops would confuse the algorithm. IPFS distributes content using a “market” algorithm, bartering for blocks of data on the network with Filecoin or with other blocks.

Each of these pocket universes of social and economic reality has its own structure and forms, its own space and geometry. Chains, and being on or off of them. Blocks of different sizes and fullness, with varying distances between them. Channels, rhizomes, shards, tangles, mines and thrones. Forests, tables, graphs, markets and identities. These formal differences distinguish different cryptocurrencies technologically and politically. Algorithmic differences are ideological differences, this is not an external critique it is internal to the logic of cryptocurrency – algorithms are changed to better instantiate what is just. These algorithmic differences produce formal differences. Their surplus value and unintended consequences continue this process of critique-in-code.

The question of the shape of the blockchain opens up onto a space of technomic, geometric and social forms. We can move through the hyperspace containing and relating these forms to the specific spaces of individual blockchains that are built around them, through the constraints and agendas that they reflect, out into wider society. The gaps and overlaps in this space indicate useful problems for the work of development or critique. Given this, geometries and forms are at least as useful a navigational marker as professed intentions or revealed preferences. But only if we can imagine and visualise them.

Art deals in form, from the spatial volumes of Renaissance perspective to the choreography and logistics of Relational and Contemporary art. Whether promoting, like Jessica Angel’s public art envisioning of the Doge-Ethereum bridge as a Klein Bottle, critiquing or simply rendering perceptible the very different kinds of form that make up the geometric, technomic and social forms of the blockchain and the relationships between them, art has the unique potential to uncover the true shape of the blockchain.

Image notes:

Simple Blockchain Art Diagram, by Rhea Myers. 2016

What the Silk Road bitcoin seizure transaction network looks like, Reddit

“[A] hundred reasons present themselves, each drowning the voice of the others.” (Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations: supra note 11 § 478).

For Part 1 click HERE.

For Part 2 click HERE.

Voice and unintelligibility play a greater, complex role in reasoning than the Left or Right accelerationists are prepared to admit, or fail to see. Establishing ones political voice is far broader and extensive than any of these thinkers take it to be, and is not simply the by-product of a phenomenological given unable to envisage any political alternative. Voice has to take priority here, for how else does one actually communicate? By this, we don’t have to take Voice to be the literal act of saying something out loud, or examining the behaviour for doing so. It can interpreted both as a metaphor and means encompassing every political act to which it can be applied; having a voice, or an opinion, hearing the public representation of someone, or of a community, wanting to being heard, letting someone have a say in the matter, etc. Above all it takes on the force of voicing ones own condition.

Might every form of modern communication then, be it a WhatsApp message, a bored glance at a meeting, cynical internet comments to nondescript mumbling, be one of ordinarily voicing our own condition? Perhaps even more so when it is mediated by an infrastructure (sometimes especially so). Both Voice and infrastructure are components of communicating indirectly, as most language games tend to do, whether face to face, face to mirror or interface.

The problem with philosophy is that the ordinary gets blamed, largely as the historical list of philosophy’s complaints almost always aim for the ordinary first as if its triviality is, by itself, not to be trusted with political or rational action. Indeed the very task of calling the ordinary to our attention, takes into account that we have lost interest in it. Perhaps it was already assumed that the market silently reduces the depth of ordinary communication and circumstance to capitalist knowledge anyway. Or maybe since ordinary life is increasingly and consistently mediated through online platforms, technology has overtaken its significance.

Yet what Ordinaryism seeks to uncover is that Voice does not constrain freedom because of its vulnerability: it is only because of vulnerability that voice expresses the freedom to reason in the first place. This is the split that severs both the sovereign rationality of Accelerationism (and Sellars), and the non-sovereign self of Ordinaryism (and Cavell). Indeed, this appears to be Cavell’s political lesson: it seems rational to want build a platform for others to air their democratic voice and decry any ineffective basis in favour something more determinate, more grounded, more inhuman. Yet freedom and justice only begins if a community is capable of ‘finding’ their own voice in the face of injustice. Likewise freedom is constrained if other voices repudiate the voice of others. There is no cognitive purchase for this, and no pre-built, implicit, or explicit ground for determining intelligibility either. So we have to ask, how else can the inhuman make itself intelligible unless it gives voice to its own condition? (As an aside, what else is philosophy but a set of specific and singular voices crying out for recognition in their appeal? A voice that may be acknowledged, yet equally repudiated? Just as the sound and look of Voice matter in reasoning, [how it persuades, how it strikes you] so too does the sound and look matter to philosophising arguments and deductions.)

The easiest way to round these political concerns up is to show how the very need to bypass the vulnerability of Voice, the need to provide an ‘answer’ or ‘solution’ to that vulnerability, is the same philosophical question that concerns solving skepticism. This is the heart of Cavell’s philosophy.

Following Naomi Scheman, the heart of transcendental inhumanism to which the epistemic accelerationists follow aims to draw attention to what underlies the possibility of our ordinary lives. But in Ordinaryism, the Cavellian rejoinder must insist that “the ordinariness of our lives cannot be taken for granted; skepticism looms as the modus tollens of the transcendentalist’s modus ponens.” (Scheman, “A Storied World”, In Stanley Cavell and Literary Studies, 2011 p.99). Whereas Accelerationism posits a renewed set of tools to re-determine intelligibility in an era of supposed ‘full automation’, Ordinaryism speaks to these same conditions but where intelligibility routinely breaks down, is endlessly brittle, always delicate, sometimes connects, but is never ensured or determined by philosophical explanation alone. What might it mean to understand the fragmented world of machines as a uniquely literary responsibility?

In other words, a future world of increased automation needs a romantic alternative. And it is sorely needed, because in this future order where automation is assumed to outpace human knowledge, or supersede it in any case (amplifying existing industries, or creating new ones) Ordinaryism speaks of new moments of doubt which constitute the skeptical fragments of ordinary life with machines. Perhaps also of machines. It might take on a specific personal form of questioning and living with what these new forms takes on; “what does this foreign mapping of data really know about me”, “what does it know about all of us?”, “Am I just being used here?”, “How can I know whether anyone is spying on me?”, “why are they ignoring me?”, “what on earth does that Tweet mean?”, “what’s happening?”, “what am I supposed to think about this”, “Why would I care about you’re doing?”, “I need to know what they’re doing.”

There are innumerable ordinary circumstances where a life with machines begins to make sense, but also starts to break down in all the same places: how might one suggest that a machine “knows” what it’s doing, or that “it knows” what to do? Where does the scalability of automated systems start to break down, and what sort of skepticism does it engender when it does? What happens when software bugs, and unpredictable acts of mis-texting chagrin habitual pattern? How might such finite points of knowledge exist, so as to understand and inhabit systemic doubt? What are the singular and specific means for how such systems are built, conceived or decided? And most of all, how might we even begin to characterise and acknowledge the voices which emerge within these systems? You might say that Ordinaryism wishes to extract acknowledgement out of the knowledge economy.

What is required then, is both a Cavellian critique of epistemic accelerationism (what potential political dangers might arise if Voice is repudiated) and why its solutions to solve skepticism through collective reasoning and self-mastery are no different from skepticism itself. But to do that, one also has to take account of how Cavell brings an alternate approach to imagining how normative rules are implicit in practice. This is not an act of opposition, more of a therapy, which might be needed, especially as politics is involved.

Now, despite the fact that Cavell’s philosophical questions work (almost) exclusively in the Wittgensteinian domain of articulating and expressing normative concepts which regulate speech and pragmatic action (beginning from his first essays Must We Mean What We Say? and his later magnum opus, The Claim of Reason) these texts don’t appear to be required reading in accelerationist and neo-rationalist circles.

Take the newly released art journal Glass Bead, whose aim is to suggest that any “…claim concerning the efficacy of art – its capacity, beyond either it’s representational function or its affectivity, to make changes in the way we think of the world and act on it – first demands a renewed understanding of reason itself.” If such a change in thinking is motivated by a renewed post-analytic approach to reason in a world of complexity (and an additional capacity for aesthetic efficacy), the continued omission of Cavell’s work into reason and aesthetics, is notable by its complete and utter absence. It’s enough to warrant the claim that certain imaginings of reason – in this case the abstract inferential game of giving and asking for reasons – are to be favoured over other types (usually with a secondary, pragmatist demand that science is the only authentic means for understanding the significance of the everyday).

In fact there’s a good reason for that omission: because Cavell discovered that he wasn’t able to ignore the threat of skepticism entirely, and instead discover it to be a truth of human rationality (is there anything more paradoxical than discovering ‘a truth’ in skepticism?). He instead sought to articulate how such concepts were not inherent features of inhuman ascension by means of inferential connection, but fragmented conditions of differentiated identity. In the eyes of the epistemic accelerationist, it’s as if there isn’t any possible option in-between some half-baked, progressive ramified global plan to expand the knowledge of human rationality, and a regressive fawning over the immediacy of sensual intuition. Fortunately, Cavell’s ‘projective’ approach to rationality questions this corrosive forced choice.

Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations sets up the key differences here. Instead of using Wittgenstein’s text as an introductory tool to show how the public expression of saying something can be explained and correctly applied (as Robert Brandom pedantically attempts), Cavell paid attention to Wittgenstein’s voice, as it invokes a specific and personal literary response to what happens when we are in search of such explanatory grounds (and how they always disappoint us). Perhaps more pertinently, Wittgenstein alluded towards an effort ‘to investigate the cost of our continuous temptation to knowledge.‘ (Cavell, The Claim of Reason, p. 241) Compare this to the current neo-rational appeal which has little to no awareness that the pursuit of certain knowledge (and the unacknowledged consequences for when it will go astray) might itself be inherently unproblematic. Because reason presumably.

It’s no accident therefore that Philosophical Investigations has become one of the oddest literary feats in Western philosophy, insofar that it presents itself as a personal account, rather than a systematic one. Cavell was not only the first to prise out a Kantian insight from Wittgenstein’s text, but also to ask the simple question of why does he write like this? It’s as if every single word, every ordinary word, now takes on the full power and insight as any theoretical term of jargon: as if a theoretical vocabulary isn’t wanted or needed. Why does Wittgenstein provide provocative literary fragments to elucidate his philosophical struggles? (the infamous ‘mental cramps’) Why does he raise literary devices to flag up disappointing conclusions: where a rose possesses teeth, beetles languish in boxes, and lions speak in packs of darkness? It’s an insight which lies in acknowledging that Wittgenstein’s unique literary voice is inseparable from his philosophical ambitions. It is not that he offers an anti-skeptical account to fully fix and explain what it means to say something: nor does he posit an implicit mastering of normative concepts, whereupon said possibilities are subject to further explanation (the conditions under which cognition or experience become possible).

It’s as if the theoretical problem doesn’t come with fully understanding norms implicit in practice, but the very situation in which using words like “rules”, “freedom”, “determine”, “correct” and so on, do not have the desired theoretical effect (in the accelerationist case, freedom). These are very nice words after all, but the neo-pragmatist theory is found wanting in their full expression, sufficient to the limits given when they are spoken not as a licensed inference, but as a creative effect. Cavell’s take on language thus, is that there is always something more to words than the current practice in which they are put to use.

The appeal to Wittgenstein’s literary conditions is what motivates Cavell to suppose that his theory of norms in practice isn’t something to which words are used to line up a certain conclusion, rather, the specfic and singular non-formal ordering of ordinary words in themselves provide a certain crispness and perspicuity, as well as difficulty and confusion. As Paul Grimstad suggests:

“Cavell wonders what one would have to do to words to get out of them a certain kind of clarity; to ground their meaning in an order. A kind of literary tact—the soundof these words in this order—would then serve as the condition under which we are entitled to mean in our own, and find meaning in another’s, words. The sort of perspicacity striven for here is not a matter of lining up reasons (it would not be “formal” in the way that a proof is formal), but of an attunement to arrangements of words in specific contexts.”

As Sandra Laugier chooses to describe it, Cavell’s posing of the Ordinary Language Philosopher’s question – “What we mean when we say” arises from “what allows Austin and [the later] Wittgenstein to say what they say about what we say?” For Cavell jointly discovered a radical absence of foundation to the claims of ‘what we say’, and further still, that this absence wasn’t the mark of any lack in logical rigour or of rational certainty in the normative procedures that regulate such claims. (Laugier, Why we need Ordinary Language Philosophy – p.81)

If agreement in normative rules becomes the presupposition of mutual intelligibility, then any individual is also committed to certain consequences whereupon certain rules might fail to be intelligible. Therein lies a simple difference: the espousal of following a universally applicable rule (as Brassier holds) and everyone else wondering whether that same rule has been correctly followed.

To mean exactly what we say, or to mean anything in fact, might be contingently mismatched to the specificity of what we say and project in any given context, hence one must bare the normative challenge that *what* we mean may differ from what we say.

The ordinary is saturated with these innumerable variations of mismatch through specific and singular situations, to which our attunement is threatened: when a co-worker fails to turn up to a meeting because they misunderstood someone’s directions or when a poor sap fails to get the joke he or she is the brunt of, or when a close friend misunderstands a name in a crowded bar. These moments are not insignificant wispy moments of human limitation swallowed up in a broad history of ascension, but become the necessary exhaust that emanates from a social agreement in which the bottom of our shared communal attunement falls away. With a language, I speak, but only insofar as we are already attuned in the projections we make.

As Cavell put it in this famously long (but necessarily long) passage;

We learn and teach words in certain contexts, and then we are expected, and expect others, to be able to project them into further contexts. Nothing ensures that this projection will take place (in particular not the grasping of universals nor the grasping of books of rules), just as nothing ensures that we make, and understand, the same projections. That on the whole we do is a matter of our sharing routes of interest and feeling, modes of response, sense of humour, and of significance and of fulfilment, of what is outrageous, of what is similar to what else, what a rebuke, what forgiveness, of what an utterance is an assertion, what an appeal, when an explanation – all the whirl of activity that Wittgenstein calls “forms of life”. Human speech and activity, sanity and community, rest upon nothing more, but nothing less, than this. It is a vision as simple as it is difficult, and as difficult as it is (and because it is) terrifying. (Cavell, Must We Mean What We Say? p.52)

If the reader might allow a Zizekian-style joke here (apologies in advance), it might elucidate Cavell’s insight further than the lofty quote above: “Two guys are having an heated exchange in a bar. One goads to the other, “what would you do if I called you an arsehole?”, to which the other replies “I’d punch you without hesitation.” The first guy thinks on his feet: “well, alright, what if I thought you were an arsehole? Would you hit me then?” The second guy reflects on his reply, “well, probably not” he says, “how would I know what you’re thinking?” “That settles it then,” says the first guy, “I think you’re an arsehole.”

Although the mismatch is played to (a rather ludicrous) comical effect, it offers a way into Cavell’s strange appreciation of skepticism’s lived effect. We intuitively know these ordinary situations, ordinary utterances and yet such acts are not instances of reason ascending its limits through knowledge, but are necessary and specific instances where reason’s endless depth and vulnerability enacts itself within such limits. The intelligble process by which the concept of “I think you’re an arsehole” arises, does little only to serve how brittle the semblances between saying and thinking portray. This for Cavell produces an anxiety; and it “… lies not just in the fact that my understanding has limits, but that I must draw on them, on apparently no more ground than my own.” (Claim of Reason, p. 115).

But it also presents a shift from the commonness of ordinary language to the question of a community where that commonness resides. And for Cavell if it is the case that there’s no firmer foundation than shared practices of common speech and community, there cannot be a shared conceptual framework, so as to collectively determine an objective intelligible method of treating and avoiding skeptical claims. Thus, any instability between what we find intelligible (what we cognitively understand or grasp) and how it is expressed in what we say, is also indicative of the social and cultural conditions that sustain such vulnerabilities. This is why for Cavell, the social conditions of a language game are fundamentally aesthetic in character, because we are both attuned to the conditions of a game and the experimental moments in which one tries out new and progressive literary arrangements that push against the game’s limits.

Which is why the history of the inhuman is constitutive of skepticism as barbed wire is constitutive of blood stained fences. And in conclusion, we’ll begin a preliminary move towards a bona fide Ordinaryist alternative to epistemic accelerationism (to be fleshed out in the final part). Key to this alternative is to understand that reasoning is not explainable by rule-governed inhuman rationality, but has a hand in the general projection of words, criteria and concepts in ordinary language (and moreover how inhuman Exit threatens this reasoning). Just because political action within reasoning can often fail to be intelligible, does not render it subject to inhuman ascension.

Nonetheless, Accelerationism operates as if there’s no other type of future worth wagering on, nor any method other than the force of reason suitable enough to supply the tools required. The morality put forward hence is that the more we are able to harness our knowledge of our social and technical world, the better we will be able to effectively rule ourselves and the greater chance of a strategy to overcome capitalism. The chief rejoinders that usually face criticisms of renewing the Enlightenment, consist in labelling detractors as complicit with skepticism, misunderstanding skepticism, languishing in sophism, abandoning reason for irrationality, justification for complicity, and trading off modern knowledge for theological assumption. Brassier recently referred to this skeptical questioning as the “unassailable doxa” of the humanities, constitutive of an influential strand of 20th Century European philosophy (from Nietzsche onwards), where the desire to know is “identified with the desire to subjugate”. Brassier goes on;

This is skepticism’s perennial appeal: by encouraging us to give up the desire to know, it promises to unburden us of the labour of justification required to satisfy this philosophical desire. Thus it is not certainty that skepticism invites us to abandon, but the philosophical demand to justify our certainties.

What Brassier takes for granted however, is that refusing to adhere to the force of reason and the ongoing project of attaining knowledge does not instantly amount to embracing skepticism, or that such knowledge will always be inadequate (and a violent act). What is at stake is not *simply* an inadequacy of knowledge as a cognitive resource. To view it as this, is what Cavell associates as skepticism, even if the desire is to then overcome it, or, in some way pushing skepticism to a deeper conclusion. The issue is not sophism, but skepticism.

Cavell’s romantic inclinations towards ordinary language philosophy offers a way out of this forced choice: skepticism simply cannot be refuted in favour of a renewed inhuman anti-skepticism. Entertaining skeptical doubt isn’t something which philosophers are especially adept at, treating it as an intellectual error to refute or ward off afterwards. Skepticism inhabits itself as an everyday, ordinary occurrence, equally puzzling and troubling, eternally unsatisfied and yet utterly enticing. It is a strange, yet equally relentless human drive to repress and reject the very attuned conditions that sustain intelligibility: conditions which also contain the ability to attune to one another’s projections.

In consideration of the fact that Accelerationism wants to conceive our conditioned intelligibility as a product of rule-governed knowledge this poses problems worthy of the best tragedies the humanities have to offer. Here’s Cavell’s take on the matter (my emphasis):

I do not […] confine the term [“skepticism”] to philosophers who wind up denying that we can ever know; I apply it to any view which takes the existence of the world to be a problem of knowledge […]. I hope it will not seem perverse that I lump views in such a way, taking the very raising of the question of knowledge in a certain form, or spirit, to constitute skepticism, regardless of whether a philosophy takes itself to have answered the question affirmatively or negatively. (Cavell, The Claim of Reason, p.46).

Brassier would probably lambast this certain condition as a conformist view of ‘I should or ought to live my skepticism’, such that it hides an implicit refusal to investigate or question these forms (leading to various, inexorable ‘end of’ philosophies). But in doing so he takes on, at least in Cavell’s eyes, the compulsive epistemic assurances that skepticism compels. By implication Brassier’s endorsement of an anti-skepticism hides the fragility and depth of normative claims, and that claims are always voiced and projected. The problem with espousing rules for generating normative freedom is that a rule is neither an explanation nor a foundation – it is simply there (note that in saying this Cavell does not deny any rigour, moral or political commitments to normative rules). What Brassier and Accelerationism share is to answer a source of disquiet; that the validity of our normative claims seem to be based on nothing deeper than ourselves, or how words are put. And this attempt to reject Cavell’s insight, to erase skepticism once and for all, backfires only by reinforcing it.

Cavell’s treatment of skepticism is that it must be reconfigured away from an entrenched view of epistemological justification as a product of certainty: or that the existence of other minds, objects, procedures, processes and worlds can be reduced to problems of (and for) knowledge. The head on effort to defeat skepticism allows us to think we have explanations when in fact we lack them. Or put better, the idea that we can theorise a clean break from skepticism is itself a form of skepticism. The point is that we clearly can approach communities, other minds, systems and communities which often appear incomprehensible, unintelligible; but such appearances are features of vulnerability, and vulnerable grounds which we depend on nonetheless. Yet change only occurs not because we’re certain about the knowledge we possess, but in response to others whose involvement happens to be beyond my intellectual attempt to know them with certainty. There is nothing more uncertain than a response to alterity.

Politics operates exactly in this way, coming to terms with ones immediate response to injustice, not in “knowing” it or offering an explanation, but by acknowledging it. The “folk” vulnerabilities that Srnicek and Williams find ineffective are constitutive of intelligible injustices that we must acknowledge in order to engage at all. Nothing guarantees this. This is the central point: reasoning with the inhuman, requires a human appeal to acknowledge another – or put differently, making the inhuman intelligible requires that we acknowledge the voice of the inhuman (and equally that this same voice can reject our appeals). After all, what use is a politics based on the epistemic assurances of knowledge, if such knowledge can be regularly doubted?

What Brassier doesn’t acknowledge is that both his position and the skepticism he attacks, are guilty of the same premise: the longing for a genuine inhuman knowledge, without acknowledgment. This appeals to something greater than the everyday which gives voice to such justifications. Nihilism might be fun, but at some point its political actions soon becomes silent to its own screams, as it spins into a void of its own making. The ordinary prevails.

Cavell suggests that this philosophical impetus towards the inhuman is inherent to the skeptical habits of philosophical drive, for there is:

…inherent to philosophy a certain drive to the inhuman, to a certain inhuman idea of intellectuality, or of completion, or of the systematic; and that exactly because it is a drive to the inhuman, it is somehow itself the most inescapably human of motivations. (Conant, “An Interview with Stanley Cavell,” in Fleming & Payne, eds., The Sense of Stanley Cavell, 1989)

Unlike most ordinary language philosophers, Cavell has always been clear that the appeal to ordinary language is not the same as refuting skepticism (as some disciples of Wittgenstein might have it). Nothing is more skeptical, more aversive to the everyday that the “human wish to deny the condition of human existence” and that “as long as the denial is essential to what we think of the human, skepticism cannot, or must not, be denied.” (Cavell, In Quest of the Ordinary, 1988, p. 5) In fact, most of Accelerationism’s Promethean attempts in fully maximising the human drive to transcend itself, were preempted by Cavell: as the skeptics’s treatment of the world (and others) is endless, completely prone to acceleration. One might say, acceleration is built into skepticism when the human mind convinces itself that the world is divorced and devoid of meaning – it encounters nothing but the meaningless of itself. It becomes a tragic temptation which the human creature carries out, an internal argument that it can’t quite relinquish. Or as Cavellian scholar, Stephen Mulhall puts it simply. “the denial of fintiude is finitude’s deepest impulse.” (Mulhall, The Self and its Shadows, 2013, p.48)

Accelerationism becomes a tragedy. A tragedy of never quite knowing what knowledge is enough, or when (it’s tragic enough that in theorising the emancipatory potentials of technology, it hasn’t appeared to go any further than incessantly arguing about it with others on blogs and Facebook threads – this author included).

However this shouldn’t be too much of a surprise when you have a political movement which shares an enthusiasm for building AI systems that are (quoting Mark Zuckerberg early last year); “better than humans at our primary senses: vision, listening”. When Facebook’s CEO thinks it’s unproblematic to invent a future sending unmediated telepathic thoughts to each other using technology (and your response to this is that it’s merely constrained by neo-liberal market forces) skepticism has reached a new apex. Ordinaryism makes no conservative attempt to preserve some fabled image of humanism located outside of technology, nor provide any Heideggerian technological lament, but instead reflect on what this tragic apex of skepticism will mean for us, what it says about our condition, and how the vulnerabilities of Voice make themselves known nonetheless. More than anything, how will this new apex of skepticism change the ordinary?

No doubt the Left-Accelerationist’s hearts are in the right places: but nonetheless, the dangers become obvious. If the solution to overcoming capitalism takes on the same inhuman skeptical impulses for epistemological certainty that constitute it, what exactly stops the Left-accelerationist’s proposals from being used for reactionary purposes? What sort of decisions must it undertake to control the ordinary, and to that effect, the ordinary voices of others who might doubt their knowledge?

This is why Cavell takes skepticism to not only be the denial of reason having any epistemic certainty, but the entire explanatory quest for epistemic certainty tout court. Both are latent philosophical expressions of what he calls ‘the skeptical impulse’ and both inhabit the very denial of this impulse whilst also becoming its mode of expression. The problem with attaining knowledge of the world, isn’t knowledge, but its theoretical desire for knowledge as certainty. Brassier would have you believe that any deviation from the emancipating Platonic discipline of ascending human finitude – the desire to know – risks disengaging reason from mastering the world. Whereas in the ordinary, reasoning becomes essential because it can never master the world, only inhabit its projections. Under ordinary circumstances reason can only appeal, in numerous and multifaceted paths, experimenting with different kinds and types of intelligibility taken from a shared linguistic attunement. It’s ability to appeal is never achieved as ascendancy, but by the endless vulnerabilities of ordinary language. Intelligibility is a continual, vulnerable task, who failures become the engines for relentless re-attunement with others and the world. Exactly ‘what’ is said, ‘how’ something is said, can make all the difference: and in politics, especially so.

Reason shouldn’t and doesn’t progress by ascending itself, it progresses by tiptoe. It re-engages with the world critically, and can only appeal to others in doing the same. The moral desire of Ordinaryism is exactly this: not to exit the world, but to be in it, to be present to it, and give it and others a voice which might make that desire intelligible, so as to modify the present situation. This is why we always have to acknowledge what we say when. To show how the world attracts itself to us and how it does so in each singular and specific case. When the future comes, it’ll emerge (as it always does) in some sort of vulnerable ordinary way.

Refuting skepticism, is in itself a performative expression that simply repeats skepticism; it denies the very truth and reality of living a skeptical existence, that knowledge as certainty is an ongoing disappointment. Quoting Sami Pihlstrom, “…there is no skeptical failure here requiring a “solution”; the attempt to offer a solution is as misguided as the skeptic who asks for it.” (Pihlstrom , Pragmatic Moral Realism: A Transcendental Debate, 2005, p. 76). Once the fight to close down skepticism is enacted, accelerationism encourages its major conditions – that the problem of knowledge about the world, of other minds, of systems, global insecurities, economics becomes a problem of certainty. And yet, at the same time, Accelerationism neglects skepticism’s fundamental insight that there are specific and important problems about the role of knowledge which might have to be acknowledged. It neglects the truth of skepticism. We live our skepticism. Daily.

The surprising conclusion that arises from this quagmire, is that the skeptic is in fact right – and yet, simultaneously, skepticism is fundamentally wrong. Well, not exactly wrong: just a refusal to accept that the human creature is also a finite creature, or as Cavell put it, skepticism manifests itself as “…the interpretation of metaphysical finitude as intellectual lack.” (Cavell, In Quest of the Ordinary, 1988, p.51). As Áine Mahon puts it, “Cavell’s strategy is paradoxical: he strips s[k]eptical doubt of its power precisely by showing that it is right…. the skeptic’s doubt results from a *misunderstanding* of the truth she discovers.” (Mahon, The Ironist and the Romantic, 2014, p. 23). He takes skepticism to not only be a standing menace that denies an ordinary intimacy with the world, but also as a necessity to acknowledge ones finitude. For Ordinaryism too, also challenges political immediacy that Srnicek and Williams lament, but does so on the grounds of renewed intimacy with the ordinary. The issue is not binary: either of knowing or not-knowing, but of acknowledging (and regrettably, failing to acknowledge). The ordinary is grounded, not on knowledge (implicit or explicit), explanation, proof, logic, nor material, it’s grounded on nothing more and nothing less, than the acknowledgement of the world.

For the skeptic is in fact right, because everyday knowledge is vulnerable: the existence of the external world, other minds, and God falls outside the scope of what language can prove. Wittgenstein’s criteria can tell us what things are, but not whether things actually exist or not. This, however, does not mean that Cavell doubts the existence of things, and especially not the existence of other minds. It means that ultimately, such modes of existence must be accepted and received: moreover they have to be recovered and acknowledged.

Bracketing the abstraction here, one can immediately look to timely instances of ordinary life, in which Cavell’s ideas on skepticism seem at first distant, and then suddenly intuitive. Consider the natural, anxious reality of parenting for example (interwoven within a broad tapestry of anxiousness). I speak of first time parenting predominantly here: for doesn’t the very task of living with skepticism, responsibility and finitude, become central to the activities of childrearing and all attempts to find clear answers to the contingency, uncontrollability and unpredictability it engenders? It’s not the normative fault of parents for wanting to find something deeper, clearer and surer in order to solve the anxiousness that childrearing brings: but yet equally nothing solves it either. But there isn’t any normative basis, or universal demand for suggesting that a parent ‘ought’ to know, or ought to justify an explanation on the act of learning how to parent effectively. One simply does so, but in doing so, skepticism is not refuted, or made to temporarily vanish by competent practices alone: it is lived. More importantly, it is lived with others who also live it.

This is what Brassier’s anti-skeptical demands of accelerationism gets wrong: it makes the wrong normative demands on what ‘ought’ or ‘must’ be attained for the conditions of intelligibility to function. He makes little contention in suggesting that skepticism might also be understood as a failure to accept human finitude (Cavell, In Quest of the Ordinary, p.327), than it is a failure to justify one’s certainty in knowing. Nothing is more skeptical than the precarious efforts to reconstruct human language and communication on a more ‘rational’ or more ‘justified’ foundation, one which would avoid any need for a less tidy, ambiguous, disruptive – and above all – vulnerable aspect of ordinary expression.

It completely bypasses any option that having access to other minds and the things of this world can operate on anything other than certain knowledge. No doubt we have knowledge, and it runs deep, but it also has clear limits. As Cavell brilliantly words it; “the limitations of our knowledge are not failures of it.” (Cavell, The Claim of Reason: p. 241) Is there anything that undermines the accelerationist premise more than the ill-fated attempt to pit human knowledge against an inhuman idea of knowledge? Or if it appears that computation has no limits, neither should humans? Of course the issue here is staked in the idea that computational reason is a transcendental destiny of human knowledge, when in ordinary practice, it automates all the same vulnerabilities that chagrin us daily.