Since 2005, Inke Arns has been the curator and artist director of Hartware MedienKunstVerein, an institution focusing the cross-section between media and technology into forms of experimental and contemporary art. This year, she was the curator for the exhibition titled alien matter during transmediale festival’s thirty-year anniversary. I had the pleasure of meeting Inke and taking a leisurely stroll with her around the exhibition.

The interview is written as part of a late-night email exchange with Inke a couple of weeks following our initial meeting.

CS: How did the idea come about? In your introductory text you mention The Terminator. Were you truly watching Arnold when alien matter occurred to you as an exploratory concept?

IA: Haha, good question! No, seriously, this particular scene from Terminator 2 (1991) was sitting in the back of my head for years, maybe even decades. It’s the scene where the T-1000, a shape-shifting android, appears as the main (evil) antagonist of the T-800, played by Arnold Schwarzenegger. The T-1000 is composed of a mimetic polyalloy. His liquid metal body allows it to assume the form of other objects or people, typically terminated victims. It can use its ability to fit through narrow openings, morph its arms into bladed weapons, or change its surface colour and texture to convincingly imitate non-metallic materials. It is capable of accurately mimicking voices as well, including the ability to extrapolate a relatively small voice sample in order to generate a wider array of words or inflections as required.

The T-1000 is effectively impervious to mechanical damage: If any body part is detached, the part turns into liquid form and simply flows back into the T-1000’s body from a far range, up to 9 miles. Somehow, the strange material of the T-1000 was teaming up with Jean-Francois Lyotard’s notion of “Les Immatériaux” (1985). Lyotard tried to describe new kinds of matter, that at first sight look like something that we know of old, but in fact are materials that have been taken apart and re-assembled and therefore come to us with radically new qualities. It is essentially alien matter which Lyotard was describing.

CS: You also comment on intelligent liquid and then make reference to four subcategories for the ‘rise of new object cultures’: AI, Plastic, Infrastructure, and the Internet of Things. Is this what makes up ‘alien matter’ to you? Inorganic materials? Simultaneously, HTF The Gardener and Hard Body Trade explicitly and dominantly utilise nature.

IA: Well, the shape shifting intelligent liquid acts more like a metaphor. It is a metaphor for the fact that the clear division between active subjects and passive objects is becoming more and more blurred. Today, we are increasingly faced with active objects, with things that are acting for us. The German philosopher Günther Anders, yet another inspiration for alien matter, described in his seminal book The Obsolescence of Man (Die Antiquiertheit des Menschen) how machines – or computers – are “coming down”, how over time they have come to look less and less like machines, and how they are becoming part of the ‘background’. Or, if you wish, how they have become environment. That’s what I tried to capture in these four subcategories AI, Internet of Things, Infrastructure and Plastic. It is subcategories that reflect our contemporary situation, and at the same time are future obsolete. All of this is becoming part of the big machine that is becoming visible on the horizon. The description that Anders uses is eerily up to date.

Is this alien matter inorganic? Well, yes and no. It is primarily something inorganic as plastic could be described as one of the earliest alien matters – its qualities, like, e.g., its lifespan, are radically different from human qualities. However, it is something that increasingly merges with organic matter – Alien in Green showed this in their workshop that dealt with the xeno-hormones released by plastic and how they can be found in our own bodies. They did this by analyzing the participants’ urine samples in which they found stuff that was profoundly alien.

In the exhibition, everything is highly artificial, even if it looks like nature, like in Ignas Krunglevicius’ video Hard Body Trade or Suzanne Treister’s series of drawings/prints HFT The Gardener. The ‘natural’ is becoming increasingly polluted by potentially intelligent xeno-matter. We are advancing into murky waters.

CS: There is no use of walls in the exhibition, other than Video Palace, standing as a monumental structure made out of VHS tapes. Why did you decide to exclude setting up rooms or walls for alien matter?

IA: I knew right from the beginning that I wanted to keep the space as open as possible. Anything you build into this specific space will look kind of awkward. This is also how I make exhibitions in general: Keeping the exhibition space as open as possible, building as few separate spaces as possible in order to allow for dialogues to happen between the individual works. For alien matter we worked with raumlaborberlin, an architectural office that is known for its unusual and experimental spatial solutions and that has been working with transmediale for quite some time now. I have worked with them for the first time and I am super happy with the result. We met several times during the development process, and raumlabor proposed these amazing tripods you can see in the show. They serve as support for screens and the lighting system. (Almost) nothing is attached to the walls or the ceiling. raumlabor were very inspired by the aliens in H.G. Wells’ War of the Worlds – where the extraterrestrials are depicted with three legs and a gigantic head. Even if the show is not about aliens I really liked the idea and the appearance of these tripods. They look at the same time elegant, strange, and through their sheer size they are also a bit awe-inspiring. Strange elegant aliens so to speak to whom we have to look up in order to see. At the same time they are ‘caring’ for the exhibition, almost as if they were making sure that everything is running smoothly.

CS: What can you tell me about the narrative behind Johannes Paul Raether’s Protekto.x.x. 5.5.5.1.pcp.? You mentioned that it was originally a performance in the Apple Store, nearly branding the artist a terrorist.

IA: Correct. The figure central to the installation is one of the many fictional identities of artist Johannes Paul Raether, Protektorama. It investigates people’s obsession with their smartphones, explores portable computer systems as body prosthetics, and addresses the materiality, manufacturing, and mines of information technologies. Protektorama became known to a wider audience in July 2016 when a performance in Berlin, in which gallium—a harmless metal—was liquefied in an Apple store, led to a police operation at Kurfürstendamm. In contrast to the shrill tabloid coverage, the performative work of the witch is based on complex research and visualizations, presented here for the first time in the form of a sculptural ensemble including original audio tracks from the performance. The figure of Protektorama stems from Raether’s cyclical performance system Systema identitekturae (Identitecture), which he has been developing since 2009.

CS: Throughout the exhibition there is an awareness that technological singularity can and possibly will overcome the human body and condition. In the context of the exhibition, do you think that we may be accelerating towards technological and machinic singularity? As humans, are we already mourning the future?

IA: The technological singularity is a trans-humanist figure of thought that is currently being propagated by the mathematician Vernor Vinge and the author, inventor and Google employee Ray Kurzweil. This is understood as a point in time, and here I resort to Wikipedia, “at which machines rapidly improve themselves by way of artificial intelligence (AI) and thus accelerate technical progress in such a way that the future of humanity beyond this event is no longer predictable.” The next question you are probably going to ask is whether I believe in the singularity.

CS: Do you?

IA: Whether I believe in it? (laughs) The singularity is in fact a kind of almost theological figure. Technology and theology are very close to one another in a sense. The famous American science fiction author Arthur C. Clarke once said that any sufficiently developed technology can’t be differentiated from magic. I consider the singularity to be an interesting speculative figure of thought. Assuming the development of technology were to continue on its course as rapidly as it has to date, and Moore’s Law (stating that computing performance of computer chips doubles every 12-24 months) retained its validity, what would then be possible in 30 years? Could it really come to this tipping point of the singularity in which pure quantity is transformed into quality? I don’t know. What is interesting right now is that instead of the singularity, we are faced with something that the technology anthropologist Justin Pickart calls the ‘crapularity’: “3D printing + spam + micropayments = tribbles that you get billed for, as it replicates wildly out of control. 90% of everything is rubbish, and it’s all in your spare room – or someone else’s spare room, which you’re forced to rent through AirBnB.” I also suggest to check out the ‘Internet of Shit’ Twitter feed.

CS: You come from a literary background. Noticing the selection and curation of alien matter, it becomes clear that you love working with narratives. Do you feel as though your approach of combining narrative and speculative imaginations is fruitful and rewarding?

IA: I do (if I didn’t I wouldn’t do it). I think narrative – or: storytelling – and speculative imaginations are powerful tools of art. They allow us to see the world from a different perspective. One that is not necessarily ours, or that is maybe improbable or unthinkable today. The Russian Formalists called this (literary) procedure ‘estrangement’ (this was ten years before Bertolt Brecht with his ‘estrangement effect’). Storytelling and/or speculative imaginations help us grasping things that might be difficult to access from our or from today’s perspective. It’s like an interface into the unknown. Maybe you can compare it to learning a foreign language – it greatly helps you to understand your own native language.

CS: On a final note, I’d like to revisit a conversation we had during transmediale’s opening weekend. We spoke about a potential dichotomy or contention between the discourse followed by transmediale and that of the contemporary art world, using the review by The Guardian about the Berlin Biennial as an example. Beautifully written, albeit you seemed to disagree with some points made – particularly at the notion enforced by the writer that works shown there, similar in nature to the works in alien matter, are not ‘art’. Could you elaborate on your thoughts?

IA: You are mixing up several things – let me try to disentangle them. I was referring to the article “Welcome to the LOLhouse” published in The Guardian. The article was especially critical of the supposed cynicism and sarcasm it detected in the Berlin Biennale curators’ and most of the artists’ approaches. Well, what was true for Berlin Biennale was the fact that it showed many younger artists from the field of what some people call ‘post-Internet’ art. This generation of artists – the ‘digital natives’ – mostly grew up with digital media. And one of the realities of the all pervasive digital media is the predominance of surfaces. The generation of artists presented at the Berlin Biennale dealt a lot with these surfaces. In that sense it was a very timely and at the same time a cold reflection of the realities we are constantly faced with. I felt as if the artists held up a mirror in which today’s pervasiveness of shiny surfaces was reflected. It could be interpreted as sarcasm or cynicism – I would rather call it a realistic reflection of contemporary realities. And it was not necessarily nice what we could see in this mirror. But I liked it exactly because of this unresolved ambivalence.

About transmediale and the contemporary art world: These are in fact two worlds that merge or mix very rarely. I have often heard from people deeply involved in the field of contemporary art (even some friends of mine) that they are not interested in transmediale and/or that they would never attend the festival or go and see the exhibition. And vice versa. This is mainly due to the fact that the art people think that transmediale is too nerdy, it’s for the tech geeks (there is some truth in this), and the transmediale people are not interested in the contemporary art world as they deem it superficial (there is some truth in this as well). For my part, I am not interested in preaching to the converted. That’s why I included a lot of artists in the show that have never exhibited at transmediale before (like Joep van Liefland, Suzanne Treister, Johannes Paul Raether, Mark Leckey). However, albeit the borders, the fields have become increasingly blurred. It is also visible that what is coming more from a transmediale (or ‘media art’) context clearly displays a greater interest in the (politics of) infrastructures that are covered by the ever shiny surfaces (that bring along their own but different politics).

I could continue but I’d rather stop, as it is Monday morning, 3:01 am.

You can also read a review of alien matter, available here.

alien matter is on display until the 5th of March, in conjunction with the closing weekend of trasmediale. Don’t snooze on the last chance to see it!

All in-text images are courtesy of Luca Girardini, 2017 (CC NC-SA 4.0)

Main image is a still from the movie The Terminator 2 (1991)

Within the context of transmediale’s thirty-year anniversary, Inke Arns curates an exhibition titled alien matter. Housed in Haus der Kulturen der Welt, alien matter is a stand-alone product that has been worked on for more than a year, featuring thirty artists from Berlin and beyond. In the introductory text, Arns utilises her background in literature and borrows a quote from J.G. Ballard, an English novelist associated with New Wave science fiction and post apocalyptic stories. The quote reads:

The only truly alien planet is Earth. – J.G. Ballard in his essay Which Way to Inner Space?

Ballard was redefining the notion of space as ‘outer space’, seemingly beyond the Earth, and ‘inner space’ as the matter constituting the planet we live on. For him, the idea of outer space is irrelevant if we do not fully understand the components of our inner space, claiming, ‘It is inner space, not outer, that needs to be explored’. The ever increasing and accelerating modes of infrastructural and therefore environmental change caused by humans on our Earth is immense. Arns searches for the ways by which this form of change has contributed to the making of alien matter on a planet we consider secure, familiar and essentially, our home. In the age where technological advancements are so severe that machines are taking over human labour, singularity is a predominant theme whilst the human condition is reaching a deadlock in more ways than we can predict. The works shown in alien matter respond to this deadlock by shedding their status as mere objects of utility and evolve into autonomous agents, thus posing the question, ‘where does agency lie?’

Entering the space possessing alien matter, one is immediately confronted with a giant wall – not one like Trump’s, but instead a structure made out of approximately 20,000 obsolescent VHS tapes on wooden shelves. It is Joep van Liefland’s Video Palace #44, hollowed inside with a green glow coming from within at its entry point. The audience has the opportunity to enter the palace and be encapsulated within its plastic and green fluorescent walls, reminiscent perhaps of old video rental stores with an added touch of neon. The massive sculpture acts as an archaeological monument. It highlights one of Arns’ allocated subcategories encompassing alien matter, (The Outdateness of) Plastic(s); the rest are as follows: (The Outdatedness of) Artificial Intelligence, (The Outdatedness of) Infastructure and (The Outdatedness of) Internet(s) of Things.

Part of Plastic(s) is Morehshin Allahyari and Daniel Rourke’s project titled The 3D Additivist Cookbook, initially making its conceptual debut at last year’s transmediale festival. In collaboration with Ami Drach, Dov Ganchrow, Joey Holder and Kuang-Yi Ku, the Cookbook examines 3D printing as possessing innovative capabilities to further the functions of human activities in a post-human age. The 3D printer is no longer just an object for realising speculative ideas, but instead is manifested as a means of creating items that may initially (and currently) be considered alien for human utility. Kuang-Yi Ku’s contribution, The Fellatio Modification Project, for example, applies biological techniques of dentistry through 3D printing in order to enhance sexual pleasure. Through the 3D Additivist Cookbook, plastic is transformed into a material with infinite possibilities, in which may also be considered as alien because of their human unfamiliarity.

Alien and unfamiliarity is also prevalent when noticing the approach by which the works are laid out and lit throughout the exhibition. Without taking Video Palace #44 into consideration, the exhibiting space is void of walls and rooms. Instead, what we witness are erect structures, or tripods, clasping screens and lights. These architectural constructions are, as Arns points out in the interview we conducted, reminiscent of the extraterrestrial tripods invading the Earth in H.G. Wells’ science fiction novel, The War of the Worlds; initially illustrated by Warwick Goble in 1898. The perception of alien matter is enriched through this witty application of these technical requirements as audiences wander amongst unknown fabrications.

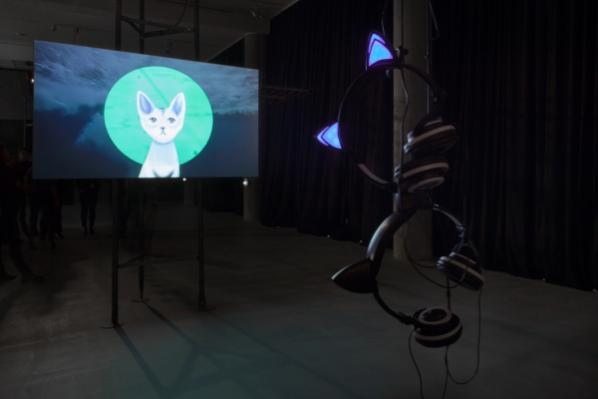

Amidst and through these alien structures, screens become manifestations for expressive AIs. Pinar Yoldas’ Artificial Intelligence for Governance, the Kitty AI envisages the world in the near future, 2039. Now, in the year 2017, Kitty AI appears to the viewer as a slightly humorous political statement, however, much of what Kitty is saying may not be far from speculation. Kitty AI appears in the form of rudimentary and aged video graphics of a cute kitten, possibly to not alarm humans with its words. It speaks against paralysed politicians, extrapolates on overloaded infrastructures of human settlement, the on-going refugee crisis still happening in 2039 but to larger dimensions and… love.

The Kitty AI is ‘running our lives, controlling all the systems it learns for us’, providing us with a politician-free zone and states that it ‘can love up to three million people at the time’ and that it ‘cares and cares about you’. Kitty AI has evolved and possesses the capacity to fulfil our most base desires and needs – solutions to problems in which human are intrinsically the cause of. Kitty AI is a perfect example when taking into consideration Paul Virilio’s theory in his book A Landscape of Events, stating:

And so we went from the metempsychosis of the evolutionary monkey to the embodiment of a human mind in an android; why not move on after that to those evolving machines whose rituals could be jolted into action by their own energy potential. – Paul Virilio in his book A Landscape of Events

Virilio doesn’t necessarily condemn the evolution of AIs; humans had the equal opportunity to progress throughout the years. Instead his concerns rise from worries that this evolution is unpredictably diminishing human agency. The starting stage for this loss of agency would be the fabrication of algorithms having the ability to speculate possible scenarios or futures. Such is the work of Nicolas Maigret and Maria Roszkowska titled Predictive Art Bot. Almost nonsensical and increasingly witty, the Predictive Art Robot borrows headlines from global market developments, purchasing behaviour, phrases from websites containing articles about digital art and hacktivism, and sometimes even crimes to create its own hypothetical, yet conceivable, storyboards. The interchange of concepts rangings from economics, to ecologies, to art, transhumanism and even medicine, pertain subjects like ‘tactical self-driving cars’ and ‘radical pranks’ for disruption and ‘political drones’ and even ‘hardcore websites perverting the female entity’.

To a certain degree, both Kitty AI and Art Predictive Bot could be seen as radical statements regarding the future of human agency, particularly in politics. There is always an underline danger regarding fading human agency and its importance for both these works and imagined scenarios – particularly when taking into consideration Sascha Pohflepp’s Recursion.

Recursion, acted by Erika Ostrander,is an attempt by an AI to speak about human ideas coming from Wikipedia, songs by The Beatles and Joni Mitchell, and even philosophy by Hegel, regarding ‘self-consciousness’, ‘sexual consciousness’, the ‘good form of the economy’, and ‘the reality of social contract’. Ostrander’s performance of the piece is almost uncanny to how we might expect AIs to understand and read through language regarding these subjects. The AI has been programmed to compose a text from these readings starting with the word ‘human’ – the result is a computer which passes a Turing test, almost mimetic of what in its own eyes is considered an ‘other’ in which we can understand that simulacra gains dialectal power as the slippage becomes mutual. Simultaneously, these words are performed by a seemingly human entity, posing the question of have we been aliens within all along without self-conscious awareness?

Throughout alien matter it becomes gradually apparent that the reason why AIs are problematic to agency is because of their ability to imitate or even be connected to a natural entity. In Ignas Krunglevičius’ video, Hard Body Trade, we are encapsulated by panoramic landscapes of mountains complimented by soothing chords and a dynamic sub-bass as a soundtrack. The AI speaks over it ‘we are sending you a message in real time’ for us to be afraid, as they are ‘the brand new’ and ‘wear masks just like you’ implying they now emulate human personas. The time-lapse continues and the AI echoes, ‘we are replacing things with math while your ideas and building in your body like fat’ – are humans reaching a point of finitude in a landscape whereby everything moves much faster than ourselves?

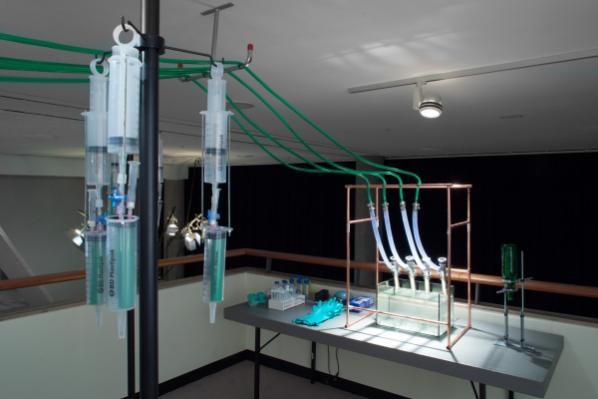

Arn’s potential resolution might be to foster environments of participation and understanding, as with the inclusion of Johannes Paul Raether’s Protektor.x.x. 5.5.5.1.pcp. Raether’s project is a participatory narrative following the daily structures of the WorldWideWitches and tells the story of an Apple Store ‘infiltration’ which took place on the 9th of July 2016 in Berlin. The performance itself was part of the Cycle Music and Art Festival and was falsely depicted by the media as scandalous; the Berliner Post called it ‘outrageous’. The performance featured Raether, wearing alien attire walking into the Store and allowing gallium to swim on the table. Gallium, as a substance is completely harmless substances to human beings, but if it touches aluminium the gallium liquid metal can completely dissolve the aluminium.

The installation is a means of communicating not only the narrative of the World Wide Witches, but to uncover the fixation that humans have with material metal objects such as iPhones. The installation itself is interactive and quite often engaged a big crowd around it, all curious to see what it was. It was placed on a table covered in a imitated form of gallium spread over cracked screens and pipes which held audio ports for the audience to listen to the WorldWideWitches story. Raether’s work, much like the exhibition as a whole, is immersive, engaging and participatory.

The exhibition precisely depicts alien matter in all its various and potential manifestations. The space, with all its constant flooding of sounds, echoes and reverbations, simulates an environment whereby the works foster intimacy not only with transmediale, but also with its audience. Indeed, Arns with a beautiful touch of curation, has fruitfully brought together the work of these gifted artists fostering an environment that is as much entertaining as it is contemplative. You can read more about Arns’ curatorial process and thoughts on alien matter through her recent interview with Furtherfield.

alien matter is on display until the 5th of March, in conjunction with the closing weekend of trasmediale. Don’t snooze on the last chance to see it!

All images are courtesy of Luca Girardini, 2017 (CC NC-SA 4.0)