Megan Prelinger is an historian/archivist (originally from Oregon) who in 2004 co-founded a bibliophile’s utopia: the Prelinger Library. Tucked away in the SOMA district of San Francisco–and now highly regarded by researchers from around the world–the library has quietly become a California landmark. The myriads of materials contained there (books and ephemera “geospatially” arranged by Megan and her partner Rick) are made available to the public at least once a week for in-situ use (and one needn’t have academic credentials to enter).

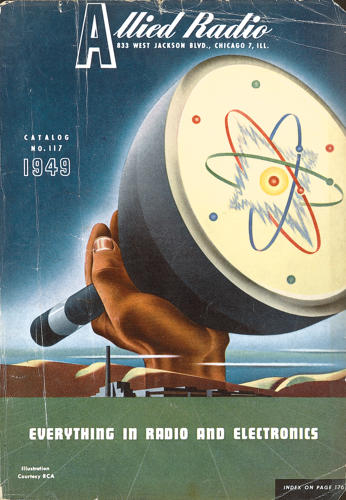

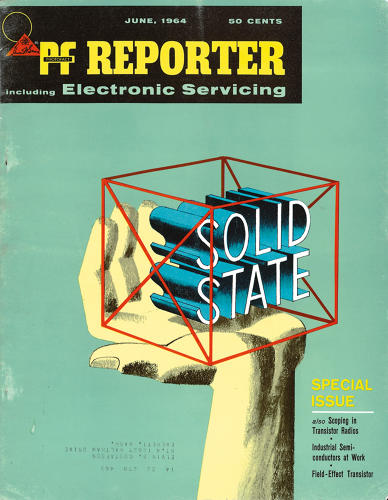

In addition to being a world-renowned sharer (and repairer!) of books though, Megan Prelinger has also authored several. Inside the Machine–her latest work–is a book that traces a visual history of all manner of electronics from roughly the interwar era to the early space age. But it derives its narrative, she says, from exactly and only one source: “the intersection of commerce and graphic art.” As with her previous book (which presents commercial artists’ depictions of early space travel and rocket tech), Inside The Machine is a story told largely through the illustrations that one finds scattered throughout archival tech ephemera–of the sort that line many a shelf at the Prelinger Library. Prelinger’s visually rich book deftly guides the reader through countless innovations that preceded today’s computers, all with an eye towards celebrating the power and reach of the human imagination.

[The following interview was conducted via email.]

Montgomery Cantsin: You say that the Prelinger Library and its community constitute the “rhythmic pulse” which sustains your work as a writer of nonfiction. I wonder if you can say a bit more about that, and how that maybe differs from the situation of many nonfiction writers–that of being ensconced in a bureaucratic university setting. Also, how much of the material in your newest book was discovered there on your own shelves in San Francisco?

Megan Prelinger: During the research and writing of Inside the Machine, between 2011 and 2014, I was simultaneously engaged in a number of projects. You ask about how my situation differs from that of an academic historian: The academic model did not fully “take” in my mind when I was younger. It was introduced to me as one option among many, and I elected take the option of being an independent and self-supporting contributor to the human knowledge project. Throughout the duration of the library project, and my life for that matter, I have therefore always engaged in a number of different types of work more or less simultaneously; types of work that fall in different places on the spectrum between “day job” and freelance artist or knowledge-producer.

My work-week during those Inside the Machine years, as before and since, was a cycle of different forms of research, engagement, and production. The common anchor point around which every week “turns” is the public day in the library that happens every Wednesday. On those public days I set aside my own work and face outward, engaging our library visitors and facilitating their work. The Wednesday community is intellectually sustaining, as hundreds of people every year who are engaged in a universe of different kinds of research-based projects stop by and spend time. Our library is a social library, with discussion being one aspect of the access model. As with visitors, the collaborative relationships I’ve had with our volunteers and artists-in-residence such as yourself have put that library environment at the center of my social, intellectual and creative life since we opened it

To answer the question about how much of the material of the book was discovered on our own shelves: The short answer is “most of it.” There are 184 images in Inside the Machine, I believe, and about 6 of them were sourced from other collections. It was the serendipitous discovery of these overlooked images that drove the research process that became both Another Science Fiction (2010), and Inside the Machine (2015).

MC: I know that your interest in space travel developed in part due to your love of Star Trek as a youth. Is your interest in electronics something that grew out of that? At what point in your career did you realize you were passionate enough about electronics to write a book? …Have you ever tinkered with the insides of machines?

MP: My love of space exploration has many antecedents and you’re correct that Star Trek: TOS is one of them. I was born in 1967 as Season Two was beginning, just in time to be exposed fairly uncritically to a regular stream of images on television that suggested that space exploration was an emerging and “normal” part of everyday life. I remember watching Apollo astronauts explore the Moon on TV, and as a small child formed the unexamined assumption that Star Trek and the Apollo program were in a fact-and-fiction relationship to one another that was analogous to the relationship between the Little House on the Prairie books (fictionalized history) and the real histories of European colonization of North America (fact).

At the same time my dad was away in Vietnam serving in the U.S. Army construction brigades, while my mom was in college studying to be an archaeologist. Mom exposed me to Native American history, and Dad exposed me to the challenges of reintegrating into society as a damaged war veteran. Dad then became an architect. Those two parental models oriented me to the ground-based world that I lived in. I grew up sharply aware of divisions in society because of these two models, and had a sense of myself as an actor in a distinctly ground-based society. I studied anthropology and became a writer in order to develop tools to understand and affect the course of society and history.

The area of my psychogeography that was shaped by visions of space exploration were filled in by science fiction, which formed a bridge between ground-based and space-based spheres. In my thirties I discovered the left-behind literature of the mid-century space industry, and discovered that those handy tools of cultural analysis and writing would enable me to make an original contribution to the cultural history of space exploration. I was gobsmacked by this discovery. It was an unexpected point of integration between realms of my intellectual life and psychogeography that had previously been united only in the lifelong practice of reading and appreciating science fiction.

Coincidentally, in the course of taking that degree in anthropology I was required in college to take a year of science as a distribution requirement. This was actually a wish come true, since part of me had wanted to be a math major from the beginning but I lacked the background to do college-level math. That year-long general science course for non-science majors was possibly my favorite class in college. One third of the years’ curriculum was devoted to exploring electronics, understanding how circuits worked, learning to read circuit diagrams, and ultimately building a simple working radio out of found materials.

When my research on the cultural history of space exploration led me to try to understand space electronics, that history was invaluable. My passion to understand electronics grew directly out of a desire to understand why space exploration technologies matured when they did, apart from geopolitics and funding streams. When I realized that space exploration in the 1950s was reliant on the simultaneous development of very large-scale computers (mainframes) and very small-scale computers (the miniaturization made possible by the transistor), I then felt an overwhelming impulse to share what I had learned with other people. Inside the Machine ended up with a space electronics chapter in the 8th position (out of 9 chapters), but space electronics was the starting point in my research and the rest of the book mushroomed out from it.

MC: The artists whose work is featured in your book (often anonymous at the time) were given the job of depicting a reality that exists, as you say, “behind reality.” You point to the inherent surrealism of such a task–can you expand on that? …You also note that in 1935, when the electric signals in the human brain were first detected, the study of the electricity, etc, was considered to be “a new assault on the mystery of life…”

MP: The study of the relationship between electricity and the human body is still pretty new. In fact, one reason that I wrote the book is that the future of the practical integration between electronics and the body could be immense enough that its recent history would be overshadowed. That history is already not commonly understood, even as people are increasingly symbiotic with their devices. I wrote the book to serve as a prehistory to counter any historical amnesia that may be induced by possible futures.

The scientific verification, in 1935, that life is reliant on a flow of electricity through the body, proved and extended an idea that Mary Shelley was working with in Frankenstein. Tracing the historical literature it’s interesting to watch the dialogue between electricity and the body migrate out of subcultures and into mainstream hard science over the past 200 years. I’m referring to subcultures like science fiction and also 19th-century experimental para-medical techniques, such as dosing people with electrical current to improve their health. That relationship was subjected to the changing standards of rigor around medical and scientific investigations over the 20th century. Today, work on electronic circuits that could have biomedical applications and that could actually be ingested and dissolved within the body is at the forefront of such research. Assuming that such circuits are developed and proven useful, I wouldn’t be surprised if they came to be a dominant biomedical technology.

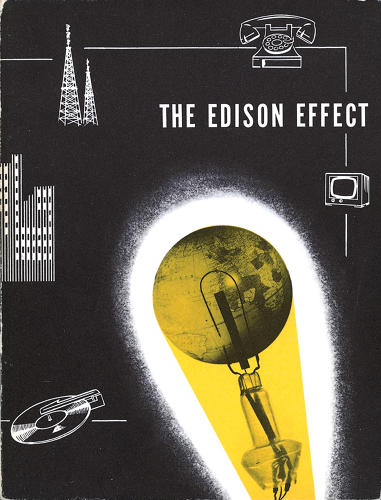

When I say “behind reality” I’m referring most literally to the invisibility of the electron stream. While electricity can be made visible as illumination, the flow of electrons through electronic devices, on the other hand, is invisible. Hence, “Inside the Machine.” For a time the components that channeled the flow of electrons, such as vacuum tubes and switches, were visible on the inside of radio cabinets. Some 1930s radio cabinet designs deliberately revealed the circuit board in a gesture to demystify the flow of electrons and glamorize the components. That short window of visibility, however, quickly retreated in the face of ever more complex circuits and ever more “built” environments that housed them. The cultural signification around electronics came to be centered on the integral devices: radio, TV, and eventually computers and everything that flows from them. I felt that there was a cultural history of the components that combine to form electronic devices that needed to be told, and that it was the graphic artists and illustrators working for industry who had made that cultural history–a history that it became my job to expose and interpret for a contemporary audience.

At a more philosophical level, the flow of electrons multiplied our senses. By forming invisible channels through which sounds and images were carried and replicated, electronics created a hierarchy of sense perceptions that had immediate cultural and political significations. How else to characterize that phenomenon besides surreal? Coincidentally the fine art movement known as Surrealism emerged in the 1920s and radios very shortly thereafter, coming to market in the late 20s and exploding in popularity during the 1930s. Think of it this way: multiple electromechanical eyes, faces, ears, and mouths populating homes, offices, and streets, in the form of a proliferation of new gadgets. The world filling with sense receptor multipliers everywhere you look. A mountaintop may be media in the sense that it opens up a perspective impossible to gain any other (unassisted) way, but a climb up a mountain is a unique event offering a unique perspective. Electronic media, in contrast, are most profound in their most ordinary distinguishing feature, which is their simultaneous multiplicity.

MC: You bring up Lewis Mumford in the book, saying that he regarded the craftperson’s bench as a sort of “bridge between art and applied skill.” To what degree has Mumford’s work influenced your thinking?

MP: I discovered the work of Lewis Mumford back in high school and appreciated his broad-spectrum thinking on a range of ground-based systems, like cities and highways. (The first book of his that I read was The Highway and the City.) Back in high school it was a novelty to me that subjects like freeways and cities were written about as subjects in their own right. They hadn’t been previously represented in any spectrum of “subjects” that I had been exposed to. I also liked about Mumford that he incorporated ecological thinking into his philosophies of the built environment, and that his environmental politics predated, and therefore did not fit into, contemporary modes of approaching those subjects.

When it came to writing Inside the Machine, I drew on Mumford, who had once been a radio engineer, as a historian of technology (or “technics” in his parlance). His work to elaborate the relationship between fine art and applied art expressed by the craft bench was a needed historical context for discussing the relationship between craft and art.

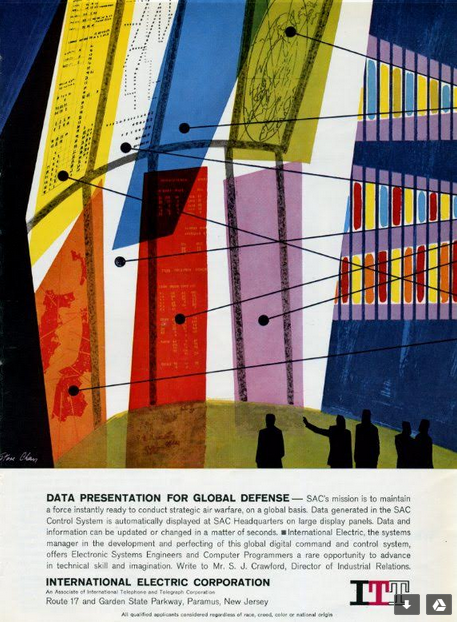

MC: The constant need for an “enlargement of the military field of perception” has been hugely responsible for innovations in moving-image technology (I am quoting here from Paul Virilio’s book War and Cinema–which I found on your shelves). I wonder how things might have developed differently if such had not been the case? (In other words, if R&D had been guided by the Teslas and the Martenots of the world instead of by Westinghouse, the Pentagon, etc.).

MP: Well… the need for an enlargement of the military field of perception may have been responsible for innovations in moving-image technology, but it must exceed that in the extent to which it influenced space technology! The original satellite programs around the world, both USSR and US, were funded and dedicated to that purpose.

To get back directly, though, to the question you pose: It’s one that opens the door to many interesting possible alternate realities. That’s one reason I became so deeply focused on the work that fine and applied artists did to paint the future of new technologies. If I can make a blanket characterization of those artists as a group: I don’t think they were motivated to pick up a pencil or brush by a desire to enlarge the military field of perception! Instead they were creating all kinds of hybrid visions of the future, including pastoral and surrealist elements that addressed the multiplication of the senses in very humane terms.

There are perhaps more examples of the possibilities you suggest than you might think. For example: the influence of Hugo Gernsback, for whom the science fiction Hugo award is named. Gernsback was an active futurist who promoted science fiction and speculative futures through the mass publication of a wide range of pulp fiction magazines. At the same time he was a serious radio and TV pioneer who founded a radio station, experimented with early television broadcasting, and published “straight” news and craft magazine for radio professionals and amateurs alike, such as Radio-Electronics and Science and Mechanics to name just two. His “straight” news and craft magazines typically had a futurist-oriented editorial edge; one that was uninterested in mapping problems or limits or real-world geopolitics onto the emergence of new technologies. I don’t doubt that Gernsback’s influence was a shaping force on the emergence of electronic technology in ways that may not be fully understood for years. I don’t mean to dwell on Gernsback — he’s been widely written about in histories and biographies and I have never felt the call to add much to his hagiography. But I’m mentioning him here to directly respond to your query of “What if (R&D had been guided by the Teslas and the Martenots of the world)”. One more note: Tesla’s name was not attached to his invention in the way that Edison’s was, but he did invent AC (alternating current). Given that most people in the industrialized world use AC every day, I would argue that Tesla did guide the research and development of some of the essential infrastructure of everyday life.

MC: Toward the end of the book you wonder whether computers will someday be “grown” instead of built. Sounds cool! Brings to my mind certain left-field figures such as Bern Porter. …Porter chose to drop out of professional science (to pursue DIY “sci-art” and many other things) after having worked on the Manhattan Project. I thought of him while looking at your book, since he is also said to have helped develop the cathode ray tube. …I am curious, what you may have learned about humanity’s future by delving into all these inventions of the past?

MP: In crafting that conclusion I was putting together a few different pieces of real evidence and combining them in a hypothetical exercise. I didn’t think it was that crazy. Consider the following verifiable phenomena: The biomedical circuits that can be ingested and dissolved in the human body; the capacity of mycelia networks–underground networks of fungal bodies—to effectively redistribute nutrients between different plants in the soil; the published theory that life itself may have emerged from primordial clay (not “soup”); the wisdom of permaculture.

I’ve read widely about all these phenomena, and other related phenomena. When I try to visualize an answer to the problem of toxic chemicals and heavy metals bound up in electronic devices, it seems reasonable to me that a hundred years from now, or maybe even only twenty years from now, people will have figured out how to extract computational functions from some combination of these kinds of existing features of the natural world. Or will have developed some intelligent permaculture that can perform media functions at the same time as producing food.

Or, never mind organic phenomena, what if all the essential elements of sand, stone, glass, (plastic) and metal that form electronic machines could be formulated and constructed to smartly dematerialize when they were no longer needed? What if you could drop a laptop into special bin that would use magnets and clean biochemical processes to disassemble all those building blocks, and distill them into measured piles and vials of raw materials for new machines?

Maybe I’ve read too much science fiction… but I’d prefer to believe that I’ve just read too much history to feel that the possibilities for the future are in any way fixed or limited. In human history–in natural history too, for that matter–epochal shifts happen sometimes “overnight” (at least in geological or historical senses), usually from the emergence of a new phenomenon that results from combined antecedents that were hidden below the surface until abruptly transformed and brought to daylight. There’s no reason to think that the dirty century of the 20th/21st centuries couldn’t experience an abrupt paradigm shift in favor of a very different kind of model.