Economic theory states that technological change comes in waves: one innovation rapidly triggers another, launching the disruptions from which new industries, workplaces and jobs are born. Steam power set in motion the industrial revolution, and likewise since the 1990s a torrent of digital and software developments have transformed industries and our working lives. But the revolutionary very quickly becomes humdrum, and once-radical and efficient innovations like the telephone, email, smartphones and Skype, become part of everyday, even mundane experience. Despite all the time-saving devices we have successfully integrated into our lives, there is a collective anxiety about the current wave of technological change and what more the future holds. Mainstream dystopian visions of our relationship with technology abound, but are we in fact engaged in a group act of cognitive dissonance: using our smartphones to read and worry about robots taking over our jobs, whilst wishing for a shorter work week and more time for creative pursuits?

The British Academy recently brought together a panel of experts in robotics, economics, retail and sociology to talk about how technology is reshaping our working lives. This review summarises some of their thoughts on the situation now, and what developments lie ahead. Watch the full debate here.

Helen Dickinson OBE reported on the British Retail Consortium’s project, Retail 2020, a practical example of how technology is changing consumer behavior and affecting firms in her industry. The UK’s retail sector has on the one hand embraced technology and created a success story. The UK has the highest ecommerce spend per head in the developed world, with c15% of transactions taking place online, and at 3.0m employees it is also the largest private sector employer in the UK. However, beneath this, internet price comparison ushered in fierce price competition. Retailers are using technology to improve manufacturing and logistic efficiencies to control costs and offset shrinking profit margins. Physical stores are closing as sales migrate online. The BRC predicts a net 900,000 jobs will be lost by 2025. Nor will the expected impact be even: deprived regions are more reliant on retail employers and so will be more affected by job losses. Likewise, the most vulnerable, with less education or skills and looking for work in their local area, will be the hardest hit.

Prof Judy Wajcman resisted the urge to overly rejoice or despair at technological developments. For her, this revolution is not so different to the waves which have come before. It is impossible to predict what new needs, wants, skills and jobs will be created by technological advances. Undoubtedly some jobs will be eliminated, others changed, and some created. However, we can certainly think beyond the immediate like-for-like: a washing machine saves labour, but it has also changed our cultural sense of what it means to be clean. Critically, we should stop thinking of technology as any kind of neutral, inevitable, unstoppable force. All technology is manmade and political, reflecting the values, biases and cultures of those creating it. As Wajcman said, ‘if we can put a man on the moon, why are women still doing so much washing?’ In other words, female subjugation to domestic labour could have been eliminated by technology, but persistent cultural norms have prevented this from happening.

Dr Sabine Hauert is a self-professed technological optimist. For her technology has the potential to make us safer and empower us, for example by reducing road accidents, or allowing those who cannot currently drive to do so. Hauert sees a future not where robots completely replace humans, but where collaborative robots work alongside them to help with specific tasks. The crucial issue for dealing with this future lies in communication and education about new technologies, since the general public, mainly informed by news and cultural media, is ill-served by a steady drip of negative stories about our future with robots.

The short film Humans Need not Apply is one such alarming production, chiming with Dr Daniel Susskind’s altogether more gloomy view of the longer term effects of technological advances on the workforce. To date, manufacturing jobs have been those most affected by automation, but traditionally white collar jobs also contain many repetitive tasks and activities (just ask the employee drumming their fingers on the photocopier). Computing advances mean that many more of these are now in scope for automation, such as the Japanese insurer replacing some underwriters with artificial intelligence. For Susskind, it is not certain that workers will continue to benefit from increased efficiencies as technology advances. A human uses a satnav provided s/he is still needed to drive, but the same satnav could just as easily interface with a self-driving car, eliminating the need for any kind of human-machine interaction. Calling to mind the wholesale changes to UK heavy industry in the 1980s, any redeployment of labour will present huge challenges, and what work eventually remains may not be enough to keep large populations in well paid, stable employment.

Can humans benefit from robots in the workplace?The panel agreed that technological change will continue apace with wide reaching ramifications for our workplaces and our wider societies, but that it is our human qualities that will give us an advantage over machines. Perhaps this is the most pressing notion: we urgently need to recalculate the value we place on tasks within society. Work where social skills, communciation, empathy, and personal interaction are prioritised (like teaching or nursing) may develop a value above that which is rewarded today.

If we smell such change coming, it is no wonder we are anxious. The panellists differed on the ability of our society to absorb and adapt to coming technological change, and the distribution of any net benefit or loss. So, is the only option to accept the inevitable and brace for the tsunami to hit? Well, no. We need to realise that ‘technology’ is not one vast, distant wave on the horizon, but a series of smaller ripples already lapping higher around our ankles. Returning to Wajcman’s point, all technologies are created by people. If innovation has a cultural dimension, it can be influenced, so we must take heart and believe in our ability to effect change.

The further we can work to democratise and widen the pool of creative engineers, developers, artists, designers and critical thinkers contributing to the development of technologies, the broader the spectrum of resulting applications and consequent benefits to society as a whole. We can be conscious in our choices as consumers as we adopt new products and services into our lives, and challenge the new social norms emerging around work and life as technology allows us to blur the boundaries between them. And finally, we need to consider who profits, and who doesn’t, from new business models. We should lobby government to be deliberate in designing policy that looks to these future developments, and their likely unequal impacts across regions, industries and populations, to ensure that existing social inequalities are not entrenched or magnified. Hopefully the creative community can help steer this wave in the right direction, painting a vivid picture of our possible futures, to persuade the powerful to act in the interests of the greater good.

Helen Dickinson OBE, Chief Executive, British Retail Consortium

Dr Sabine Hauert, Lecturer in Robotics, University of Bristol

Dr Daniel Susskind, Fellow in Economics, University of Oxford and co-author of The future of the professions: How technology will transform the work of human experts (OUP, 2015)

Professor Judy Wajcman FBA, Anthony Giddens Professor of Sociology, LSE and author Pressed for time: The acceleration of life in digital capitalism (Chicago, 2015)

Timandra Harkness, Journalist and author, Big Data: Does size matter? (Bloomsbury Sigma, 2016)

Katharine Dwyer is an artist who considers the modern corporate workplace in her practice.

Do you believe everything you said today? How can you trust what you feel? What is it about today’s truth that makes it so difficult to believe?

The journalistic affectation for pre-fixing all manner of phenomena with the term ‘post-’ has become commonplace over the last few decades. Post-capitalism, post-growth, post-normal, post-internet, post-work and post-truth are all concepts crystalizing around a pervasive sense of uncertainty, instability and social unrest. While I have the honour of guest editing the Furtherfield website for the next few months, I am hoping to bring together a number of writers, artists and thinkers who will, in various ways, explore two of the ‘post-s’ I find most urgent and compelling: post-truth and post-work.

Consolidated by Brexit and the US presidential campaign, and designated as word of the year 2016 by the Oxford Dictionary, ‘post-truth’ is now a term deeply engrained in the social and political imaginary. Since ‘post’ can signify the internalization of phenomena (the internet is inside us all), one might even say we are post-post-truth, living with it as a general condition of our reality. The post-truth condition privileges narrative over facts, appealing to people’s beliefs, ideologies, prejudices and assumptions, rather than presenting them with ‘evidence’. This is, of course, nothing new – facts have never been anything without subjective processes of interpretation, contextualization, manipulation and propaganda. As Simon Jenkins points out, ‘Of all golden-age fallacies, none is dafter than that there was a time when politicians purveyed unvarnished truth’ – lies are, he suggests, the ‘raw material’ of political narrative.

Social media holds the potential to both exacerbate and alleviate the chaos of post-truth reality. On the one hand the echo-chambers created by partisan social media feeds limit and blinker us; on the other, social media is a weapon being deployed by armies of citizen journalists and organizations committed to fact-checking and exposing political lies and obfuscation. To feel uncomfortable about the confusion and psychological strain arising from the post-truth condition is surely a reasonable human response. As Professor Dan Kahan suggests:

‘we should be anxious that in a certain kind of environment, where facts become invested with significance that turns them almost into badges of membership in and loyalty to groups, that we’re not going to be making sense of the information in a way that we can trust. We’re going to be unconsciously fitting what we see to the stake we have in maintaining our standing in the group, and I don’t think that’s what anyone wants to do with their reason’

What Kahan points to here is, I think, an opportunity to reflect carefully on the stake we have in maintaining our sense of identity and belonging through the ‘facts’ we choose to believe. Despite the discomfort we may feel, might there be a way to take advantage of this cultural moment? Perhaps recognizing our own doubts about credibility can become a fruitful catalyst for adjusting our sense of responsibility to engage with a range of news sources, listen to opposing points of view, and critically evaluate the information we are presented with. In fact, Kahan prescribes 10 minutes of doubt every morning to deal with the anxiety that arises from a feeling that you can’t trust your own feelings.

Can we have a good life without work, or is work part of what it means to live a decent life? What would you do if you didn’t have to work?

One of the most significant societal shifts taking place due to the advancement of technology is the transformation of what it means to work, and to be a worker. The nine to five is dead (or soon will be), and work is being radically transformed as a new global workforce comes online, technological innovations advance at super high speed, and new business models emerge. Automation is now a firm feature of mainstream discourse, and depictions of robots replacing jobs are everywhere in the global media imaginary.

The Bank of England’s chief economist recently projected that 15 million UK jobs will be lost to automation in the next 2 decades, which is equivalent to approximately 80 million US jobs. 47% of white collar jobs are predicted to be lost to automation by 2035, according to a 2016 report by Citi GPS and the Oxford Martin School at the University of Oxford. It is not just routine tasks that will be replaced – asset management, analytics, patient care, law, construction and financial trading can all be done (and is being done) by robots. Mining giant Rio Tinto already uses 45 240-ton driverless trucks to move iron ore in two Australian mines, saying it is cheaper and safer than using human drivers.

At the same time as these developments are evolving at break neck speed, we are living in an increasingly unequal world, where the gap between the rich and poor is getting bigger. According to a recent Oxfam report, 62 identifiable individuals own same wealth as poorest 50% of the world’s population – that’s 3.6 billion people. And 1% of the world’s population own more than the rest of us combined. Capital grows faster than labour, so if you’re already rich, your money earns more than your labour ever could, which reinforces existing wealth inequality. Furthermore, extreme inequality involves people thinking greedily about finite resources, and not seeing personal greed as having wider consequences. If people see that the 1% own more than the rest, there’s danger their response is to play same game and look to join that 1% (or 5%/10%)

Not everyone is equally equipped to deal with the changes ahead, but since artists, designers and critical thinkers are amongst the best-resourced to do so, I see it as our responsibility to consider how we can help others deal with what lies ahead. As with confronting post-truth reality, acknowledging a post-work future can be seen as an opportunity to forge a better path forward for ourselves and others. We might take a cue from what we know about post-truth, and try to create narratives (backed up by collectively verified facts) that persuade the world to proceed towards an equitable world of work where solidarity and cooperation can thrive.

The articles gathered over the next two months as part of my guest editorship of Furtherfield might be understood as moments of corrective doubt. They are an opportunity to speculate about issues of truth and labour, and to proceed as artists should – by imagining alternative realities and evolving conceptual, aesthetic and practical ways to inhabit them. You can expect revelations about the labour conditions of those who work for contemporary artists from Ronald Flanagan, reflections on robots in the workplace from Katharine Dwyer, and an interview about the repopulation of Monopoly with cryptocurrencies from Francesca Baglietto. Filippo Lorenzin will consider Dada as a response to the post-truth condition, Carleigh Morgan will consider what makes good curatorial practice in this contemporary moment, reorienting current discussions away from free speech absolutism vs censorship to questions of judgement and responsibility. Alex McLean will use the metaphor of weaving to consider the role of craft in a post-work society. How might coding be understood as a form of textile liberated from its militaristic origins?

Happy doubting to all.

Featured image: XRay by Claude Chuzel

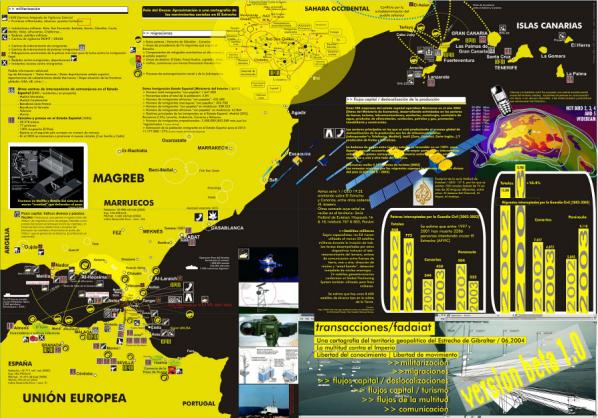

“One of the most consequential outcomes of this ubiquitous mode of organization of social life is that we have become so accustomed to relating to space in “either/or” and “here/there” terms that we have become mentally trapped inside this binary border-based model, making it difficult to imagine alternative ways of territorial organization.” Popescu [1a]

Maps inform us where things are situated. The borders depicted in each map propose a different view on the social conditions, attitudes, and interactions with others in the world. The AntiAtlas of borders project shows us different approaches for understanding “the mutations of control systems along land, sea, air and virtual states” and their borders. It has done this through the combined contributions of social and ‘hard’ science researchers and artists, all engaged in creative practices including Internet art, tactical geography, filmmakers, performers and hackers. The project also includes other relevant actors such as people working as professionals for customs agencies, surveillance industries and the military.

This is the first of two interviews with Isabelle Arvers who has collaborated with the IMERA team (the Mediterranean Institute for Advanced Research of Aix-Marseille University), to curate this expansive and dynamic project. The first interview discusses the operational side of the project and the next interview examines selected writings, artworks, projects and ideas featured as part of the project.

Marc Garrett: Before we begin the interview it would great if you could tell us when and where the exhibitions, events, publications and other parts of the project begin?

Isabelle Arvers: The AntiAtlas programme will run from 30 September 2013 to 1 March 2014 and will be composed of five initiatives: an inaugural international symposium, two exhibitions, a website and the publication of a book. The International Conference will be held from 30 September – 2 October 2013 at the New Conservatory of Aix en Provence. The main aim of this conference is to present the results of the interdisciplinary workshops that took place in the last two years at IMéRA et at the Higher School of Art of Aix-en-Provence.

The AntiAtlas of borders will present two interlinked exhibitions. The first will take place in Aix-en-Provence at the Musée des Tapisseries from 1 October to 3 November 2013. The second will take place in Marseille at La Compagnie creative arts centre from 13 December 2013 to 1 March 2014. The two exhibitions will present works developed in collaboration with social scientists, researchers in the hard sciences and artists. They will offer several levels of reading and forms of participation. Visitors will discover new works, engage with transmedia documentation and participate in experiments. They will interact directly with robots, drones, video games, walls and systems. The aim is to encourage everyone to reflect on how we are directly and personally affected by the transformations of borders in the 21st century.

The final version of the website www.antiatlas.net/eng is an online extension of the exhibitions. Most importantly, the website provides access to works of net.art and artistic interventions in the form of an online gallery of works. This website and its documentation will extend the progress and reach achieved by the project. It will act as an archive and documentation site for the general public, artists, researchers and institutions.

In 2014, an AntiAtlas of border publication will be produced, gathering publications of researchers and artists on different and selected themes of the international conference and the two exhibitions.

MG: What has been your involvement with AntiAtlas?

IA: When I met the IMERA team (the Mediterranean Institute for Advanced Research of Aix-Marseille University), they were looking for a curator in order to disseminate the outcomes of the past three years of seminars they conducted on borders. I saw this project as a great opportunity as there was a political dimension within it that attracted me. Also, I am deeply interested in tactical media and tactical geography and by new forms of visualisation and new aesthetics related to systems of control like drones, robots, satellites or surveillance cameras.

I wanted to create a participatory event that would allow people to follow our work online and offline. I also wanted to mix different kinds of works from research in the hard and social sciences to artistic installations, websites, games and videos. To do so, we decided to create a website www.antiatlas.net that would gather artworks, research articles and interviews, an online gallery and also all the presentations given during the different seminars conducted by IMERA on borders during the last three years. Thanks to the website, we were able to launch a call for proposals as I wanted to get the testimonies and the voice of migrants about their vision on borders.

Very quickly we understood that we needed to get more funding and partners, so I offered to seek media, private and institutional partnerships as well as to manage the communication of the entire event. This fundraising was needed to promote a global vision of the antiAtlas of borders and to link all the parts of the event: from the website, to the call for proposal, till the international seminar and the two exhibitions. Because of my multiple engagements in the project, I became one of the 5 co-producers of the programme.

MG: This is a complex project. It is noticeable that there is a diverse and dynamic, cross section of different practices being bridged to make it all happen. Has it been difficult to combine all of these practices so they can relate to each other coherently?

IS: Combining all these different practices was a wonderful and exciting adventure. During one year and a half, we worked very closely with the scientific and artistic committee and tried to exchange as much as possible between different visions and ways of working. I learned a lot from researchers and was amazed by the deep understanding and knowledge they have on the subject of borders. Thanks to their research and to their approaches to this issue, I was able to get a very diverse understanding of this complex subject. From me, they discovered the online communication and the power of the web and social networks to diffuse and share the information. They also got a better understanding of the tactical media field and we learned so much from each other that this experience is already a beautiful success in sharing and learning from passionate human beings. I come from media art world and I tried to respond to a scenario that the committee conceived with artists’ works, which is a very different way for me to work. This time I had a script to follow; the way I did it was to try to find some ludic interactive installations, as well as documentary projects or games, in order to allow the experimentation of the subject by the audience. They trusted me even if it wasn’t a field they knew well.

MG: Do you feel that it has de-compartmentalised these varied fields of knowledge successfully?

IS: What was particularly positive in the last seminars on borders we organised was that they allowed plenty of time to discuss and facilitate the exchange between the different perspectives. A specific example is a game project resulting from the collaboration between an anthropologist – Cédric Parizot – and a interactive laboratory from the Superior art School of Aix-en-Provence, which is led by the artist and game designer Douglas Edric Stanley. The idea is to create a “crossing industry game” drawing on the data collected by Cédric Parizot on trafficking. The collaboration addressed the visualisation, contextualisation and re-appropriation of a field of knowledge through game mechanics. I think that this experience really enriched all the team. The anthropologist was able to analyse his data in a different way, while the interactive students got closer to the reality of trafficking as they were experiencing through a game.

There are many other cross-disciplinary projects made in the framework of the AntiAtlas. I would say that what we want is to multiply different experiences and forms of knowledge on borders across and between the separate but intersecting fields of art and science. The exhibition is conceived to mix everything: research through the documentation space, researchers’ interviews, counter cartographies, interactive installations on biometrics and surveillance technologies, applications to divert control systems and documentaries providing a wider point of view on multiple dimensions of borders and their representations. Artists and researchers meet three times per year, some of them collaborate on trans-disciplinary projects, so that the conditions to meet and de-compartmentalise these fields are created. This is only the beginning. The process still needs to be pushed and facilitated as the antiAtlas is an attempt to create a new kind of cross-disciplinary encounter, let’s see how it will evolve!

This first interview with Arvers attended to organisational and operational aspects of the inter-disciplinary border-crossing within AntiAtlas project. The complex task of collating, sharing and collaborating to make it all happen at all could use its own map. The processes and engagements that evolved as the project took shape involved a collaboration of many different fields and practices, individuals, groups, organisations and cross cultural relations. This transdisciplinary approach helps us to unpack the deep levels of the meanings and value of crossing borders, in an organisational sense. Their dedication to transcend the seemingly ‘scripted’ blockages and restraints echoes a strong feeling that we need to re-assess the maps given to us, and what this means.

“What is needed to escape the modern mental “territorial trap” are ways of seeing and drawing that reveal what the geographical abstraction of the borderline obscures. It is only in this way, then, that we will acquire the necessary tools to think through a technologically enabled world of border flows and portals” Popescu.[1b]

Isabelle Arvers is an independent author, critic and exhibition curator. She specializes in the immaterial, bringing together art, video games, Internet and new forms of images by using networks and digital imagery. She has organized a large number of exhibitions in France and overseas (Australia, Canada, Brazil, Norway, Italy, Germany) and collaborates regularly with the Centre Pompidou and French and international festivals. http://www.isabellearvers.com/