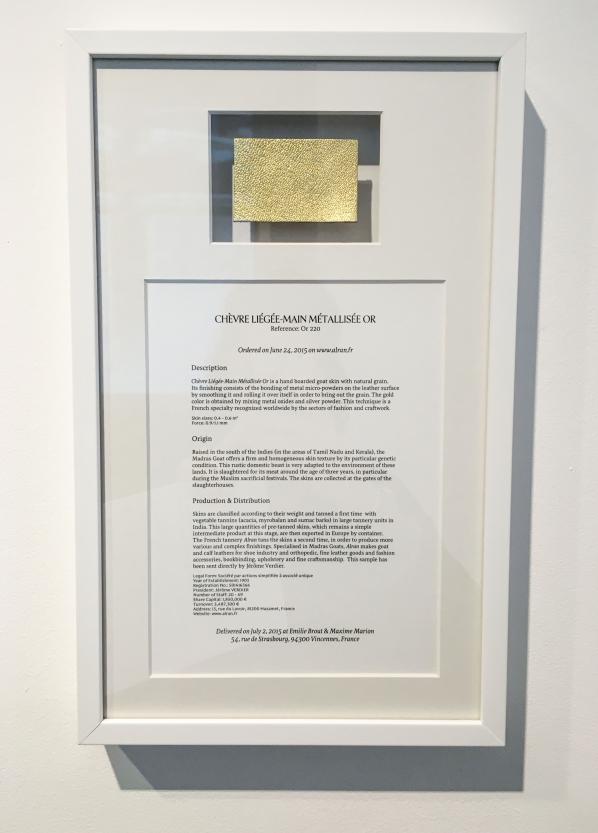

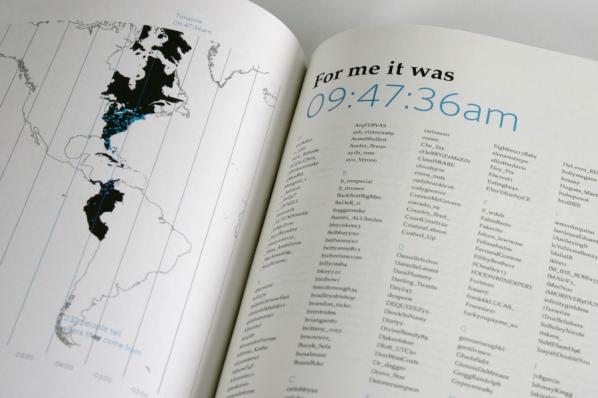

Featured image: Image from When Drones Fall From the Sky, by Craig Whitlock, Washington Post. [link]

At 0213 ZULU on the 2 March 2013, a Predator drone, tail number 04-3133, impacted the ground 7 nautical miles southwest of Kandahar Air Base, Afghanistan, and was destroyed with a loss valued at $4,688,557.[1]

On the 27th March 2007, a crashed spy plane was discovered by Yemeni military officials in the southern province of Hadramaut, along the country’s Arabian Sea coastline. The following day, Yemen’s state media identified the plane as being of Iranian origin, and that it was yet another example of an Iranian provocation at a time of high diplomatic tensions between the two countries. It was three years later, upon Wikileaks’ release of the so-called Cablegate archive, that a US Embassy cable revealed the “Iranian spy plane” was in fact a “Scan Eagle” drone. The drone was remotely piloted from the US Navy’s USS Ashland which was patrolling the Arabian Sea as part of an international counterterror task force. The United States Military was not “officially” conducting military operations in Yemeni territory at the time, and had not sought permission to conduct operations in the country’s airspace.

The discovery of the crashed drone could have posed a difficult political problem for the US to solve. However, in the cable, the official makes it clear that Yemen’s President Saleh had been keen to reach an agreeable deal with the Americans and apportion blame on a convenient third party — Iran. The cable states:

“He could have taken the opportunity to score political points by appearing tough in public against the United States, but chose instead to blame Iran. No doubt focused on the unrest in Saada and our support for the transfer of excess armored personnel carriers from neighboring countries (reftel), Saleh decided he would benefit more from painting Iran as the bad guy in this case.” [2]

By 2007, aside from occasional reporting in the media and among some activist circles, there was little public awareness of the US drone program. In fact, the program was not officially acknowledged on-the-record by a US government official until 2012. This official was John O. Brennan, then Counterterror Advisor to Barack Obama, and the momentous occasion was a speech at Washington DC’s Wilson Centre—a “key non-partisan policy forum for tackling global issues through independent research and open dialogue”.[3] Brennan states:

“So let me say it as simply as I can. Yes, in full accordance with the law—and in order to prevent terrorist attacks on the United States and to save American lives—the United States Government conducts targeted strikes against specific al-Qa’ida terrorists, sometimes using remotely piloted aircraft, often referred to publicly as drones.”[4]

While the use of unmanned aircraft in warfare goes back to the early 20th Century[5], the distinctive image of the drone has come to characterise the ambiguous geopolitics of The Global War on Terror. Their hubristic names—Reapers, Predators — evoke visions of carnivorous animals carefully and selectively stalking their prey. With their stealth and capacity to observe targets for hours on end before striking, the drone selectively adopts the tactics of the insurgency: it is an emergent weapon directed onto an emergent threat. Drones, like their intended targets, are not necessarily contained by borderlines, or to territories on which the US has declared war. They are in a suspended state of exception, and are decried both as being outright illegal by experts in international law, and simultaneously, as Brennan contests, strictly adherent to the doctrine of Just War.

In Brennan’s Wilson Centre speech, he draws on medical analogies to justify the “wisdom” of drone warfare, emphasising its “surgical precision—the ability, with laser-like focus, to eliminate the cancerous tumor called an al-Qa’ida terrorist while limiting damage to the tissue around it—that makes this counterterrorism tool so essential.”[6] But are drones as precise as Brennan’s rhetoric implies? Drones are often said to be heard, and not seen—their whirring noise inspiring local derisive colloquialisms[7]. But it is especially in the drone crash that the drone can be seen, and what’s more, subjected to inspection. It alerts us to a vital consideration: the failure of so-called precision military technology.

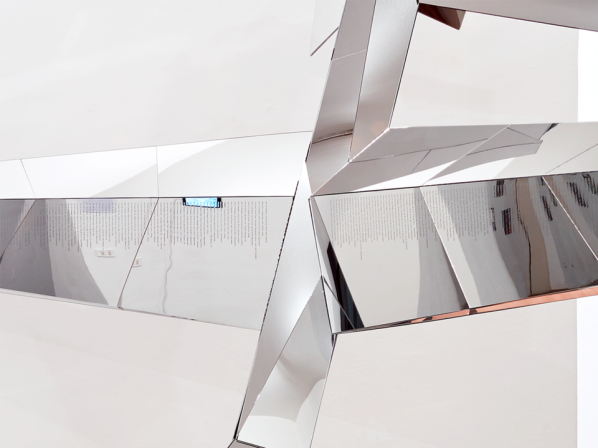

In IOCOSE‘s Drone Memorial, our attention is drawn to the fact that these complex systems are precarious, that the drone is indeed a fallible technology. The memorial, a sculpture of a fallen Predator drone driven into a copper plinth like a blade, subverts the surgical metaphor proposed by John O. Brennan. The drone’s mirrored surfaces create a fractured, tesselated reflection of its surroundings, its form almost vanishing in a specular camouflage. Inscribed on its wings are the memorial’s “fallen comrades”, the hundreds of other drones that have crashed, listed by location and date. This list can only be considered a selection, however, such is the secrecy around the use of drones in the War on Terror. As such, it should also be considered a monument to the journalists who manage to report on the discrete events of drone warfare in incredibly challenging circumstances.

A GPS beacon embedded in Drone Memorial broadcasts the location of the sculpture on the project website, hinting to us that this seemingly trivial technology in our smartphones has more nefarious uses. Global Positioning Systems have their roots in Cold War ballistics research, specifically in a program by DARPA codenamed TRANSIT, developed to direct the US Navy submarine missiles to “within tens of meters of a target”[8]. Today, GPS is one of many components in the assemblage of technologies used in the drone, and a key enabler of its apparent “precision”. Nevertheless, GPS can of course fail—it can be “jammed” inadvertently, or indeed tactically manipulated by malicious third parties. When the satellite link is lost with a drone, the aircraft goes into a holding pattern, flying autonomously until control is regained. In the Washington Post‘s story “When Drones Fall From the Sky”, they note that in order to keep its weight at a minimum there is little redundancy built into the drone’s on-board systems. Without backup power supplies, transponders and GPS links fail, and in several cases “drones simply disappeared and were never found.”[9]

IOCOSE’s positioning of the memorial as existing in a hypothetical, post-war scenario poses some interesting questions, but this temporal dissociation is perhaps unnecessary, for this is an issue very much of the present. It is certainly a topic more than worthy of critical investigation—the spectacle and the political consequences of failure have largely been left out of typical artistic engagement with drone warfare. In their press release accompanying the work[10], the artists suggest that the sculpture has an absurd quality. To me, it is not absurd as much as it works as an apt memorial to the violence of failure. In reading the long list of drone crash locations, the viewer might begin to probe the question of what information should be open to public scrutiny. IOCOSE pose the following question to us: “Does a drone crash count as a technological failure, or as a casualty?” This question would appear to have a clear answer: we must see the drone crash as a technological failure, so as not to make a false equivalence with the real casualties of drone warfare—the civilians who are subjected to it, the very same people who might also counter Brennan’s claims that the drone is a surgical, precise weapon of war.

Drone Memorial is the third work in a series titled In Times of Peace. This most recent work is the most astute in challenging the legally and ethically disruptive paradigm of drone warfare: it pierces the reflective rhetoric of US defense officials, and directs our attention to the high-stakes violence of its technological failure. The memorial, of course, ordinarily comes after the historical moment. This ‘moment’ is very much still unfolding 15 years later, and as the Trump administration takes form, it seems that the way in which drones will be deployed in the future is an ‘unknown unknown’. Thus, Drone Memorial is a temporal snapshot, an aesthetic pause on an ongoing, mutable war that seems to operate on a parallel continuum, only occasionally visible. More drones will continue to fail, as the drone war inevitably continues. These failures present a moment for critical analysis, a flash of visibility that should be seized upon.

Featured image: Pandora’s Dropbox by Matt Bower

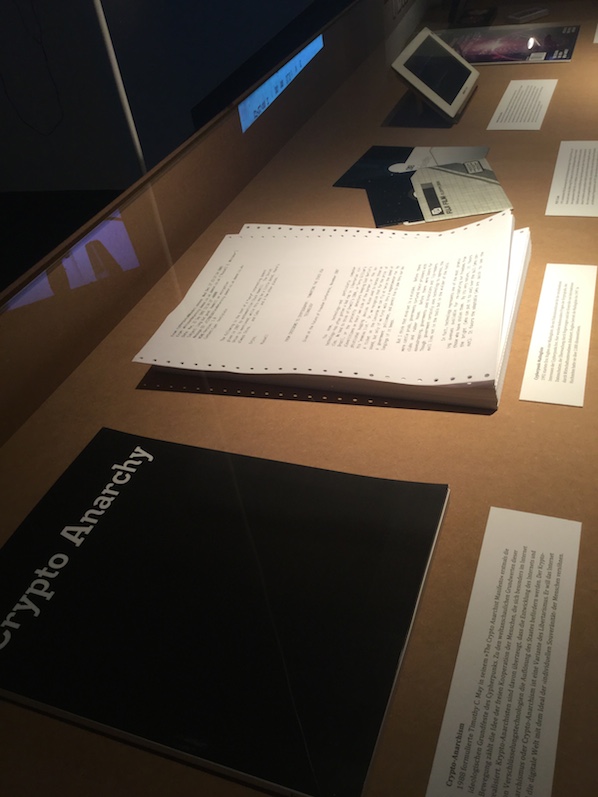

The Disruption Network Lab (DNL) has been presenting in Berlin some of the finest platforms for the discussion of art, hacktivism and disruption, presenting academic debates on not-so-conventional forms of thought. In their event IGNORANCE: The Power of Non-Knowledge, the second in the series Art and Evidence, various scientists and researchers discussed ignorance, not merely as a subaltern issue but as a central tool in knowledge production.

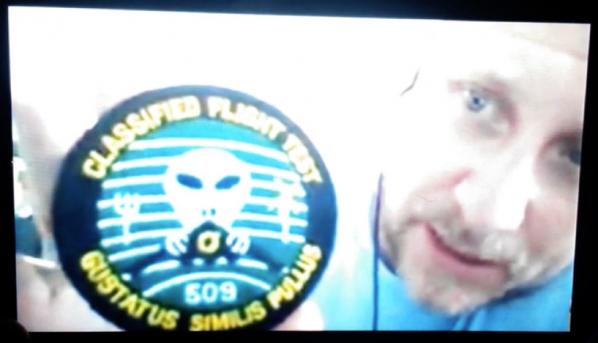

In previous events, DNL debated how ignorance is deployed as a mechanism of truth and power negotiation, mainly through the omission of the known by the means of secrecy, obfuscation and military classification. There are many forms of understanding ignorance, and this program intended to elucidate the potentialities and pitfalls within the concept. According to DNL, the first step towards approaching ignorance is to recognise it and become aware of it. As co-curator of DNL Daniela Silvestrin said (despite the paradox) that it is necessary to render the “unknown unknown into a known unknown.” The field of ignorance studies investigates the spread of ignorance, what kind of forms it takes depending on the context, how science “converts” it into probabilistic calculations of risk, and even how it can be used to push certain political, economical or religious agendas.

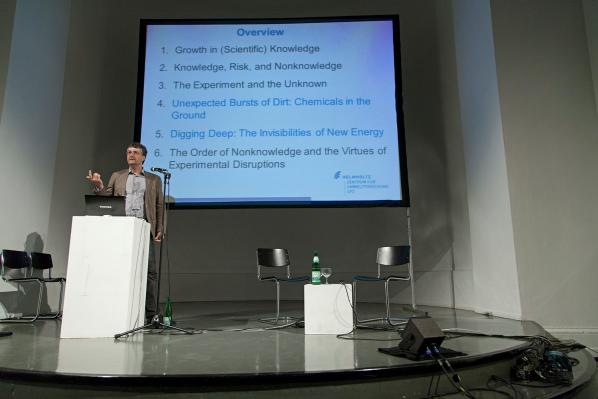

In the opening keynote, Matthias Gross, a sociologist and science studies scholar who has written extensively on ignorance studies, co-editing with Linsey McGoey the “Handbook of Ignorance Studies,” starts by stating that “new knowledge always creates new ignorance” and that throughout history humans have been in constant relation – acceptance, denial, resignation – with the unknown. Gross has covered how ignorance operates in different scientific milieus, namely, how risk is widely used in natural sciences as an attempt to project an idea of the future, as demonstrated in weather forecasting, but also how not knowing operates in everyday life; through secrets, the spread of false knowledge, feigning ignorance, or even through actively not wanting to know.

Gross presented a compelling body of research, exposing numerous examples in which ignorance serves the purpose as a tool to acknowledge what we don’t know in science (important in fields such as Epidemiology) or how positions of power use ignorance to manipulate public opinion within our social structures. However, the debate felt somehow stranded in an optimistic loop, where ignorance was seen mostly as a catalyst to search for further knowledge. Yet, I believe, while duelling with the binary knowledge vs ignorance, one should never forget to tackle the universalistic shape that ‘knowledge’ tends to adopt. In the end, the discussion felt insufficient, failing to examine knowledge/ ignorance from a non-hegemonic perspective when it would have been interesting to borrow criticism from postcolonial or feminist thought.

The first panel, moderated by Teresa Dillon, was deemed to shake the consensus in the room by joining the moralistic perspectives in science, the forbidden and undesired, the paranormal and the apocryphal together. Sociologist Joanna Kempner presented astonishing research focused on ‘negative knowledge,’ described as taboo, dangerous or threatening to the status quo. In an attempt to demystify the neutrality of knowledge production in sciences, Kempner interviewed various scientists to discover forbidden areas in their fields. The outcome of this research revealed that due to a fear of loss of funding and/ or sullying their reputation, scientists restrain themselves from researching illegitimate topics. For example, in Psychology one is expected not to study extra-sensory/ paranormal senses as these studies are usually associated to parasciences, a term that is in itself revealing of the hierarchies of knowledge. Kempner also exemplified how knowledge production is pressured by political interests and recalled the research-bans during the G.W.Bush government that cut funds to research related to sex and drugs under the assumption that remaining ignorant about any possible positive aspects (of recreational drug consumption) guarantees the maintenance of conservative moral values.

On the maintenance of moral values, the philosopher Jan Wieland presented an interesting experiment: “What would you do if you wouldn’t know? And what would you do if you’d know?” Giving the example of a social experiment by Fashion Revolution, a movement that calls for “greater transparency in the fashion industry”, Wieland examined consumers’ choices as they acknowledged the conditions in which clothing is actually produced. The project invokes a sentimental story with an excerpt from the daily life of a young girl living in Dhaka, Bangladesh, who works in a garment factory. Coming to terms with the girl’s story, the reactions differed — from not buying and empathically connecting with her situation to total indifference and still buying. Wieland attempts to analytically evaluate their intentions, good or bad, and how ignorance affects choices, stating that some of us might willfully remain ignorant (willful ignorance) as a way to better cope with our habits of consumption. However, I find it difficult to extrapolate these findings to a moralistic and individualistic criticism of people’s consumerist choices, since we know there is a structure that keeps consumers far from well-informed. A good example of how economy capitalises on ignorance, we know that the international division of labour is intentionally built to alienate the consumers from the “dirty” phases of production.

Jamie Allen, artist and researcher, also analyses at the economy of non-knowledge that is in the genesis of apocryphal technologies. “Do pedestrian’s crossroads’ buttons actually work?” We have all thought about this, yet has it stopped us from pressing the buttons? As long as we do not know whether a certain technology actually works, it “works”. Such an economy is boosted by acknowledging that some things remain as common ignorance. If we are not sure whether a lie detector works or not, then it can be used to incriminate — amidst ignorance, it shall produce the truth.

Informative and somewhat frightening, “Merchants of Doubt”, directed by Robert Kenner (2014), reveals how bendable ‘truth’ is in the interests of big corporations. The documentary investigates how the tobacco industry spread false information among firefighters, leading the world to believe that the domestic fires caused by cigarettes were the fault of the furniture rather than the cigarettes. This is where it goes from uncannily funny to scary. While interviewing scientists, whistleblowers and activists, the film unveils the dreadful story of corporate campaigns designed to unleash confusion and scientific scepticism among the masses, putting the life and security of millions at stake. This scepticism is not passive, thus it turns into a cynical endeavour. As corporations claim that there is no consensus surrounding issues such as global warming, conferences and books are forged to sustain their statement, while scientists who defend the existence of greenhouse gases are accused of ceding to their political biases in order to get funding for their research. What about facts? They seem to become irrelevant in the face of expensive lies.

Watch Merchants of Doubt’s trailer here.

Karen Douglas, a social psychologist, presented an empirical study of conspiracy theories whilst trying to trace a particular psychological profile of those more prone to elaborate and believe in them. Douglas used widely known conspiracy theories as examples, such as the infamous car crash that killed Princess Diana (which became a true “Schrödinger’s cat” case, instigated by the media-produced hyperreality in which Diana was both alive and dead — along with Elvis Presley) and the theory that 9/11 was orchestrated by the United States government to instigate and justify the “war on terror”. Douglas believes we are naturally hardwired to believe in conspiracy theories and sees them as a way to cope with things we are unable to answer. A socio-analytical view on conspiracy theories also seems to fail the complexity of forces that make us consider why certain theories are conspiracies and other perspectives are just theories. The issue with Douglas’ approach lies within its socio-psychological analysis, which tries to find a pathological pattern in people who believe in conspiracy theories, such as describing these people as being intentionally biased, or stating that those who tend to perceive patterns in things or believe in more than one conspiracy theory all show the “symptoms” of a conspiracy theorist. Yet, as pointed out by a member of the audience, this approach seems to lack a sensibility to the entire concept of “conspiracy theory” as a political tool to dismiss and undermine other narratives, such as narratives from an undesired other (e.g. how Russia’s government agenda is seen by the USA). Nevertheless, it is interesting to understand how these bodies of “disbelief”, should you wish to call them conspiracy theories or not, have a huge impact on our lives and inevitably our deaths (e.g. global warming, vaccination). As with apocryphal technologies, certain forms of unknown seem to crystallise as forms of knowledge – we know that we do not know and that is the way it is.

The closing panel, moderated by Tatiana Bazzichelli, has overseen our entanglement on social media and its algorithms, promising to be oracles of truth while their complex structures grow beyond our understanding. Ippolita, a group of activists and writers, warned how social media promotes emotional pornography, where our feelings are exploited by click baits in exchange for our personal data. By establishing clear metrics of interaction, like the number of likes and comments, social media creates an addictive game of forged interactivity, while we are scrutinised by biometric evaluation resultant from the same data we produce. Also analysing the manipulation of data and its weight in political agendas, Hannah Parkison, a journalist focused on digital culture, analysed Trump’s run for presidency propaganda in digital media. By using mostly social networks, such as Facebook and Twitter, Trump has kept control of his narrative without entering into risky interviews broadcast on TV. This is an effective way to get away with lies, regardless of the constant warnings from fact checkers – according to Politict 78% of what Trump said on the run for the election is not factually true. These lies spread across the internet, rendering their own truth.

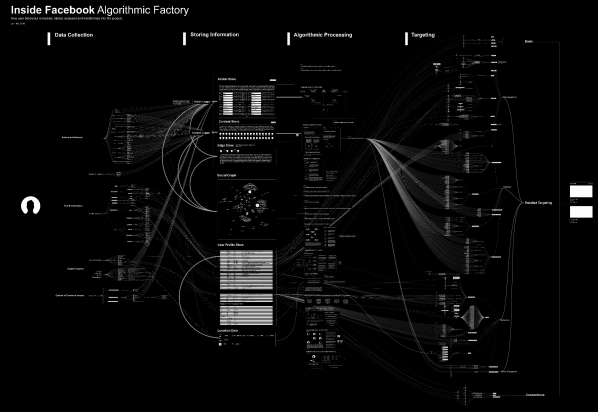

Vladan Joler, chair of New Media Department at the University of Novi Sad, presented his project in which he tries to map the tentacular structure of the Facebook algorithm, an expansive database incorporating individuals’ personal information that implies the fabrication of assumptions about potential consumers’ habits, wants and needs. Facebook was thus framed as an immaterial factory of information, the functioning of its assembly line still unknown, constantly mutating and growing. A speculative visual image of Facebook’s processes was rendered as Vladan tried to map something unknown; this mapping has similarities to the work of early cartographers. And much like early anthropological stances, the nodes of information produced have the potential to define thoughts and discussions about what we are and how we are supposed to behave. As Vladan ironically concluded, these are the tools used by the cybernet dominators – the digital monarchies that will accentuate asymmetries.

Ideas such as ‘knowledge’ find resistance and defiance from other epistemes that fall out from the western-centric productions of knowledge, such as the Amerindian ‘perspectivism’ defended by Viveiros de Castro or even the Alien phenomenologies (see Ian Bogost) that instigate the thought of non-anthropocentric ontologies. Bearing those in mind, I found that talking about the ‘dark’ side of knowledge is an invitation to dismantle and boycott its mechanisms of production, sustained in frail ideas of “truth”, “reality”, or “science”. In addition to the initial concept of ignorance, the conference provided a fertile ground for questioning the multiple ways in which humans deal with intangible phenomena, try to bypass obscurity and profit from that same obscurity. It provided insight on the relevance of knowledge to map and create reality, while bodies of power render webs of mystification of the tangible – corporations forging lies, politics of manipulation, cultural colonisation – reproducing ad nauseam epistemic violence.

The third edition of the Art and Evidence series from Disruption Network Lab, which took place on the 25th and 26th of November, wrapped up with the event TRUTH-TELLERS: The Impact of Speaking Out. TRUTH-TELLERS asks a question that could not be more crucial at the moment: “Can we trust the sources and can the sources trust us?” We have recently experienced a presidential battle between Clinton and Trump in which one of the most divisive topics were the thousands of emails sent to and from Hillary Clinton’s private email server while she was Secretary of State. A battle from which Trump left victorious despite having failed almost every fact-checking test. While Assange is forbidden to use the Internet for fear of him interfering with the presidential run in the USA, Chelsea Manning remains convicted, sentenced to 35 years of imprisonment due to her 2013 accusations of violating the Espionage Act. DNL gathered hacktivists, privacy advocates, investigative journalists, artists and researchers to “reflect on the consequences of leaking and whistleblowing from a political, cultural and technological perspective”. Unfortunately, due to a lack of funding, this could have been the very last DNL event. Let’s hope not, as these are vital, particularly in times of political despair.

Feature image: Still from Dreams Rewired: original source Das Auge der Welt (Germany 1935); dir: C. Hartmann

Dreams Rewired / Mobilisierung der Träume – Trailer from Amour Fou on Vimeo.

The 2015 film Dreams Rewired, recently shown at the Watermans Digital Weekender in London on 12-13 November, will be screened again at Watermans on 3 December. Directed by Manu Luksch, Martin Reinhardt and Thomas Tode, the film has the tagline ‘Every age thinks it’s the modern age’. It looks back to the early 20th Century, to the development and implementation (first locally, then globally) of the telephone, the radio and television.

The makers of Dreams Rewired unearthed and arranged early film recordings and brought them into the 21st century context. This was done via a playful narrative written by Manu Luksch and Mukul Patel and read by Tilda Swinton. The tagline was well chosen; almost everything Swinton says would have been relevant at almost any point within the last century. Time periods, machineries and political movements are connected in clever and unexpected ways, meaning that Dreams Rewired, a durational video whose narrative follows a recognisable storytelling structure, makes numerous links between times, places and people, which branch off from the safety of its linear structure.

Dreams Rewired is something of a treasure trove, not only for the glimpses its found-footage building-blocks gives into a past era but also because of the inter-generational, inter-national, inter-thematic connections it makes. Frequently while watching the film I felt the urge to burrow into an investigation of one of the clips, stories or introduced contexts. To emulate this ‘tip of the iceberg’ effect, this review will pull words directly from the film, linking quotations to some of the themes which appear and reappear throughout.

“A new electric intimacy”

With new media come new practices of communication. One of the recurring themes described in Dreams Rewired is the coupling of intimacy and invasion of privacy introduced to society along with a new communication method. Just as a new invention is prototyped, its social implementation causes new prototypical behaviours – new ways of caring, new ways of injuring, new comings-together, new separations. Uncertainty is inherent to experimentation.

“The waves travel at the speed of light, defining what simultaneous means. Information can travel no faster.”

When something is newly possible it also newly achievable – new precedents are set and new avenues opened for exploration. There is a flurry of activity, a rapid diversification. For those looking to gain or retain power over others, this is a problem; diversity requires more effort to manage. Initial flurries of activity are curtailed by the introduction of rules, the setting of precedents.

This limitation sets new targets to meet, new challenges to overcome. The cycle starts again as those in power look for ways to consolidate it while those without look to gain what they can. This is a simplistic, but not inaccurate, description of the machinery of the capitalist world.

This cycle of diversification and restriction is always coupled with the establishment and transcendence of thresholds. Experimentation with a new technology reveals some of its limits. (Side note – of course, what is understood as a limit is defined by wider cultural contexts.) “Information can travel no faster” is a provocation to speed up.

“Geography is history”

New advances cause conceptual shifts. Early telephony and television shrunk the gap in time between a thought or plan and its activation. Understandings of time and geography changed, and it became possible to move into new spaces and in new ways at socially impressive speeds. New powers, in short, were available to those who knew how to access them, to those who understood the preceding context well.

“A model of the new human is put into circulation”

A network grows, its complexity and partner processes intensifying. The machinery of daily life is altered, and daily life is a testing ground. Social interactions change as the new set of behaviours required to work the new machinery collide with existing social norms and rituals. New jobs and new workplace structures appear and people previously without responsibility or power find themselves in contact with it (though they may not understand the possibilities at first). People are no longer the same beings as before. Cycles of experimentation and consolidation reach into the body.

“Someone will have to lift us up. But who will lift them up?”

The flurry of excitement surrounding a new invention is based on the idea that ‘our’ lives will be improved, that ‘we’ will be able to do, see, have more. There is a problem here. The words ‘we’ and ‘us’ are too abstract – they bracket whoever the speaker wants them to bracket and recapitulate the prejudices they have. Anyone who is not included as part of the ‘we’ simply does not exist. This is convenient for the ‘us’ – while ‘we’ rush excitedly towards a future in which we have more and better, what ‘they’ do is of little concern. The ‘us’ does not care – or even think much – about the ‘them’. The ‘us’ cannot understand why the ‘them’ has not joined the ‘us’. After all, the ‘us’ is at a new threshold – who would not want to reach the other side?

“Personal profiles, passwords, biometrics..fully documented. Every trace filed. Bigger data, better analytics. Opt out, and we lose our place in the world. So…we share the keys to our desire, our habits, to ourselves.”

To be part of the ‘us’ and the ‘we’ requires effort. To ‘opt in’ requires sacrifice. At the same time, ‘opting in’ is the easiest thing in the world when ‘opting out’ means facing a void. Advice on how to do well, how to achieve, how to be healthy is easy to come by, but there is little guidance for those who find themselves, or wish themselves, outside the mainframe. Losing one’s place in the world means losing access to that mainframe and the stability that comes with a highly legible structure. Today the legible structure is far-reaching and well established, to the extent that opting out is dealt with violently. The new models of human coming into circulation have trouble recognising the old. There is a mutual rejection.

“Government regulation stifles amateur culture – military and commercial interests occupy most of the spectrum … transmission becomes a privilege, not a right”

As I wrote earlier, the ‘us’ and ‘them’ structure is too simple. It would be more accurate to think of people as communicating on multiple frequencies. The machinery of society is complicated to say the least, and made more so by the mainframe, which amplifies transmissions at some frequencies while restricting others. In the early 20th Century, multiple obscure radio channels were repressed, responsibility placed with public backlash following rumours that amateur radio was responsible for the sinking of the Titanic. Side questions: where did the rumours come from? What were they based on? How was the public response measured?

“For the first time he hears himself as others do. A voice absolutely familiar but estranged…But her power also grows: by controlling his voice she controls her time”

There is a strange relationship between the controller and the controlled. For every CEO there is a team whose own agenda seeps into the workings of the company. Dislocated power and fragmented or unplaceable identity are some of the symptoms of a complex system undergoing change. When a system is so complex as to involve multiple timescales, spaces, materials and structures, it is impossible to predict the future.

—

Dreams Rewired is part of the Technology is Not Neutral Symposium

3 December 2016

Watermans, London

https://www.watermans.org.uk/events/technology-is-not-neutral-symposium/

Two years after his death, Harun Farocki continues to maintain an archetypal role in the world of the visual arts. Many mourned for the loss of a gifted artist who was as not just a filmmaker but a critic, activist and philosopher en masse. Farocki succeeded his German New Wave filmic predecessors as his work would seamlessly and at once command hilarity, disparagement and intellect. A project-retrospective collaboration of his work was undertaken, just two years after his death, with its first part at The Institut Valencià d’Art Modern (IVAM) named ‘What is at Stake’, and more recently the second-part titled ‘Empathy’at the Fundació Antoni Tàpies compiled of at least 8 works focusing on an analysis of labour within the framework of capitalist demands.

The title of the exhibition, ‘Empathy’ originates from Ancient Greek; ‘εμπάθεια’ is a compound of ‘έν’ and ‘πάθος’ meaning ‘moved by passion’. In German, empathy translates to ‘Einfühlung’ and was ironically exploited by Farocki in 2008 as the title for his text and reads:

‘A compound of Eindringen (to penetrate) and Mitfühlen (to sympathize). Somewhat forceful sympathy. It should be possible to empathize in such a way that is produces the effect of alienation.’

Taking into account Farocki’s liking of Brechtian ‘distanciation’, he formulated rather quickly that to ‘empathise’ means to project one’s own feelings, therefore infiltrating objective opinion. The notion of ‘empathy’ for Farocki was carefully tailored to a synthesis that gave him the patience to be simultaneaously attentive and austere towards his subjects’ predicaments. As paradoxical as it may seem, empathy and distance are nurtured companions. With Farocki’s interpretation of empathy in mind, I entered the dark bunker where the retrospective took place. A space usually leaking brightness from the glass roof was now transformed into an industrious zone of projections, obsolete TV sets and the mellifluous humming of those operative machines. Farocki’s filmic oeuvre overflowed from devices onto white surfaces, accentuating the techno-capitalistic condition of labour operating eradically for our Western communities.

As you enter, the video-installation of Workers Leaving the Factory in Eleven Decades (2006) dominates the center. Twelve TV monitors are laid out in a horizontal line, juxtaposing chronologically the moment where the worker leaves the factory in Farocki’s twelve chosen films – among them, Workers Leaving the Lumiére Factory in Lyon (1895), Deserto Rosso (1964) and Dancer in the Dark (2000). Here, the excerpts are used as a mnemonic tool as Farocki’s montage gravitates around the entrance of each factory. Each scene extrapolates the repetition of entering as a rhetorical techne, an emphatic mimesis of organising and preserving power through the image of the factory and its systems of subjugation. Yet, distance and empathy are circular and procedural.

Curated to encourage a clockwise movement following the introductory piece, A New Product (2012) is being televised to the left. It commences during a mundane corporate board meeting for a consulting company violently regurgitating neoliberal logic. The goal of the meeting is to amplify competition and ascertain efficiency of their employees in the workplace by creation of a new product. Through the repetitive flipping of charts and reports, Farocki succeeds in capturing the vocabulary of rationalisation regarding their employees’ assets while unfolding the dynamics of the team and its public presentation. The narrative’s structure being static and unobtrusive, in conjunction with the ascetic use of the camera implies a degree of distancing from the subject. Still, the absence of Farocki’s own evaluation additionally contains the capability to bolster the viewer’s assessment of the situation thus achieving the artist’s desired equilibrium between empathy and distancing.

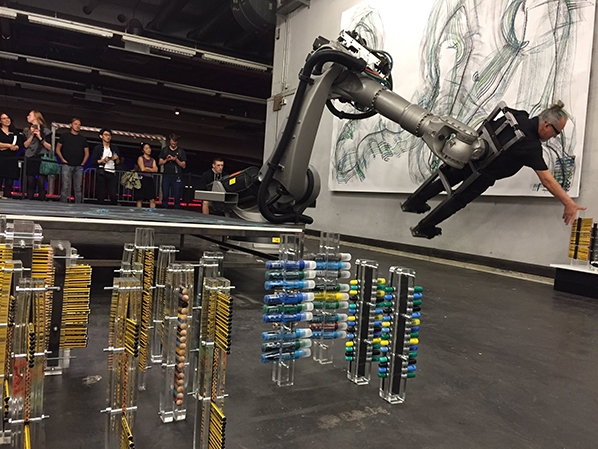

There existed a sense of rituality by which the projections were transmuted from a seemingly simple and observational nature, to one which was filled with the allegory of transparency and distance. Re-pouring (2010) was an ode to Tomas Scmidt’s Cycle for Water Buckets (or Bottles) from 1959. The original piece was a carefully choreographed mise-en-scene by which Scmidt poured one glass, a bottle of bucket of water into another. The act of pouring for Schmidt was one which indicated a simple and natural process of vaporisation with each pouring. Farocki had programmed machines to perform the artistic gesture for him, a re-pouring of the performative fluxus notion. A paradoxical act, since as human beings our navigational processes depend heavily on our cognitive ability, the mechanical hands were able to seamlessly perform the act of re-pouring. Farocki’s hyperrealism allows him to jump to a certain scale of futurity whilst also being rigorous of scrutinizing reality. The act of programming robots to perform a ritualistic and performative task goes undoubtebly implies distancing from the artistic practice of Fluxus. The Fluxus movement was predominantly a practice governed by experimental notions of performativity which were heavily conceptual. It therefore comes into stark contrast to the idea that such act could be thought by algorithm machines as notions of ‘thinking/feeling machines’ in contemporary society are rudimental and dreams of a future imagination. Farocki, able to perform the task himself such as with Indistinguishable Fire, does not. He steps out, physically distances himself from undertaking the task himself but maintains his empathy to former Fluxus activities but also expressing a empathy towards machines who today perform most human labour.

Amidst one of the spectacular accummulations of Farocki’s body of work, the apogee of the retrospective would be Labour in a Single Shot, shown for the first time in Spain. The project was initiated in 2011 by Harun Farocki and Antje Ehmann, co-curator of the retrospective. Located in an entirely different bunker, the work was compiled from a series of workshops whereby a fixed camera filmed paid, unpaid, material and immaterial labour from fifteen workshop locations. Projection screens are hanged in a room, most facing eachother whilst the noise of all labour taking place floods the space. Harmonious parallels are created as sequences from butcher shops and surgeries face eachother. The repetitive looping and sequencing of labour is used as a means of distancing and signifies non-judgmental watching as an active practice of iconic power. Our lasting impression is a call-girl sucking on a lollipop explaining how her artifice encourages clients into believing the gratification she provides is sincere. Here, we understand that just as she, through sex, retains empathy and distance in unison, Farocki’s empathy can thrive.

Featured image: The Refusal of Time, film still, courtesy William Kentridge, Marian Goodman Gallery, Goodman Gallery and Lia Rumma Gallery

There is a show of art by W K now in town. My friend, if you see but one show of art works this year or the next one or yet the next I beg of you see this one. The world of these works is both our world and not our world. The world of these works is thick and dense with rune and script and sign and light. And do you know the show is called THICK TIME and this seems as they say bang on for there is a sense in which the world and all that we are in it is here boiled down is made dense or thick. And it flows in front of us and we can see in what way and where from and where to it flows. Rune and script and sign and glyph and folk and things are drawn with ink or shown with torn or cut up scraps or light yes light much of it. And since light then dark too. Yes dark. This world flows yes and this world jumps and swells and shakes too.

And song and sound. There is song and there is sound of all kinds. There is a drum a big loud drum and a thing which marks time tick tock tick tock. There are sweet sounds and harsh sounds too. There is song. And there is change. Things change this way and that. This world will fill you with joy and at times it might make you sick at heart. It will make your head ache and pulse and spin. You might need to close your eyes. This world will speed your pulse and make you sweat. You start to dance when you see this world. You might smile. You might cry. You might have as they say a lump in your throat. W. K sees the world as we see it and knows our world as we know it and sees a world that we don’t see and we don’t know and shows it to us and now we think why did we not know this world it was there in front of us all that time.

Please note W K makes stuff with his hands. That is what he does and then he makes the stuff move. He makes things come and he makes things go and he makes things flow or stay still, he makes a world but he is not a God. He makes art. This is art. If you say to me what is art I would say art is a thing like this. The best of art is a thing like this. This is rich. This is not poor thin soup but a meal we can feast on for a long time and then come back for more. (And when we come back we will find things we did not see or taste the first time!)

He is like us and in this lies his strength. And I think he likes us and in this too lies his strength. Oh and did I say he does tricks with chairs.

I will tell you more. Let us as they say zoom in. In the first room is a pair of lungs or things that stand for lungs. Things made of wood and nail and screw and cloth which go back and forth as if they pump and move the air. And there are screens and on the screens is light and dark. Folk walk and dance. W K too is on the screens. He does tricks with chairs (and hats too) and he walks. I think I saw once he had a stick but I might be wrong. Once he bore a young girl round his neck and walked with her on the screen. He looks you might say sad but no more as if he is in deep thought. He looks at the world. And there are such sounds now here now there it is like a spell. It is a sweet pain. And there is print and type—there are words and there are sums. Now there now crossed out now smudged now clear to read but hard to grasp what it all means.

What does ‘means’ mean? What does it mean to say art, or a work of art, means? Hmm. Though not hard for sure to feel. Not thoughts but a way to feel. The strange words and the maths make you feel. The words and the dance and what you see on the screens make you sad and glad too (and your heart beats fast). And there are folk who come and go in a long line like in a march they come and go. They come in one end and walk and dance and march and then they go out. And you smile and you think hard and you see them there and then you are there and you are them. Oh a dream of life. Oh a real hard life. Oh a life of hard dream. All pass us by. King and queen and poor and knave and prince and thief and saint and the well and the sick those who live and those who will all too soon die and those who have died they pass by us, and show us the way things are and the way things might be, both the best and the worst of it. There is filth and dirt and there is joy and a bright light and there is dark and there is space. Look! It goes on and on dark and dark. The man ails—the girl does a dance. The man jigs a jig—the girl is sick. The bird flies. The old man lives—the young girl dies. A man is in a fat suit. He looks like a great white pea. She plays a tune on a thing of brass. The clock ticks. And ticks. Oh look now there is a flash. A flash of light. It is so bright. There is death. There is an end. But look now things flow once more. There is life. Here is a new start.

Things in a row. Things put in a row in a space, the right space. A space on a wall a space in a screen a screen in a space a space in a space. A gap. A pause. To look at— to put in the right space since this will help to make us feel and see what it might be like to be one who is not us.

I want to say W K is not cool. He dares much and this can make him trip and fall. (One piece I will not say which is not as good as the rest. What do you think?) He might fall on his face. At times he lacks grace. But so do we all. He does not fear this fact and this gives him strength. He does not seem to fear what folk might think. I like this. I do not like cool. I do not care for when art folk act as if they do not feel or they do not fear or hurt or love. As if this is not the stuff of our short life. And I do not like it when they claim this lack is good that to not feel is for them some sort of good thing.

There are six rooms in all I think and all will make you feel and make you think new thoughts and a warm shock will run down your spine now and then in all those rooms. (One just one is not so good I think. Which one do you think it might be?)

There comes a point where words cease to be of help. Where they lose their point or at least their edge. For just think if we could gloss the whole of a work of art why would she or he who made it want to make it—the art ? There comes a point where words must stop where we must look and feel and not say. And if we know when to stop it seems to me we are wise and we know how to live. And in a way I think this work might help us to know how to live.

Michael Szpakowski October 2016

A Book Review for Benjamin Peters’ How Not to Network a Nation: The Uneasy History of the Soviet Internet, The MITPress, 2016

“At the philosophical scale, the abundance of information and the plurality of worldviews now accessible to us through the internet is not producing a coherent consensus reality, but one riven by fundamentalist insistence on simplistic narratives, conspiracy theories, and post-factual politics. We do not seem to be able to exist within the shifting grey zone revealed to us by our increasingly ubiquitous information technologies, and instead resort to desperate modification strategies, bombarding it from the air with images and opinions in order to disperse and clarify it. It’s not working.” -James Bridle [1]

In Benjamin Peters’ “How not to Network a Nation” we learn that the USSR had the engineers with the technical knowhow and capacity to construct national computer networks of scale. Indeed, the Soviet military had such a network already in the 60s, but the question Peters wants to ask is why the USSR did not develop a ‘civilian’ computer network akin to the Internet we know and love today. The USSR did not develop a ‘civilian computer network’ because there was officially no part of the society which was independent of the state. Also, by the time anything approximating what we call the Internet began to emerge in the US, the USSR was already deep in decline. Thus, Peters’ question is moot and he only finds what is obvious from the beginning: that the social system of the USSR was incompatible with the liberal information-sphere of the capitalist West.

The book, though, should be praised for opening up and translating to English various documents, not yet available, which describe the work of early Soviet cyberneticists, and for mapping the institutional vicissitudes of the USSR at the time. We learn, for instance, about the brilliant cyberneticists Anatoly Kitov and Viktor Glushkov and their travails attempting to gather institutional support for a national civilian computer network in the USSR. Glushkov’s atrophied OGAS project forms the central narrative of the book, a project for an Inter-network of computers proposed years before Vint Cerf coined the term Internet in 1972. However, rather than appreciating the precocious cybernetic accomplishments of early Soviet theory, Peters blandly uses the “failure” of the OGAS to argue that the USSR was too perversely corrupt and bureaucratic to let progress take its course.

“Because the OGAS threatened to reorganize the social and economic spheres of life into the kind of national planned system that the command economy imagined itself to be in principle, it threatened the very practice of Soviet economic life: in [Eric P.] Hoffman’s analysis, “creates more choice and accountability and threatens firmly established formal and informal bases of power throughout the entrenched bureaucracies” [2]

Interdisciplinary historical studies of the academic, philosophical life of the USSR in English are sorely needed. Peters is sadly not sufficiently technically competent to give the reader any substantial insight into the structural concepts or proposals of the early USSR cyberneticists. It is certainly not clear from the information in the book whether any of the proposals would have produced anything akin to the Internet. In order to compensate for inadequate knowledge of political economy Peters sadly defaults to half-hearted liberal reproaches.

“Glushkov’s vision directly opposed the informal economy of mutual favours that oiled the corroded gears of Soviet production. In the end, the OGAS Project fell short because, by committing to rationalize and reform the heterarchical mess that was the command economy in practice, it promised to encourage the rational resolution of informal conflicts of interest — which worked against the instinct to preserve the personal power of almost every actor that it sought to network.”[3]

For readers interested in how the various prototype networks in the USSR (the OGAS, ESS and EASU) technically actually worked, anything about the USSR military computer network (analogous to ARPANET), how USSR computer industry differed from that of the capitalist countries, o how USSR computer theory differed from that of the capitalist countries, the book experience will be disappointing; it has too little of this. What’s really lacking is a strong attachment to the subject, the meat and bones of the OGAS, its material scale, how the projects actually ran, on a daily basis. Peters’ seems more passionately concerned with reasserting that capitalism is better than socialism because it produced the Internet.

Peters’ thesis is specious: “The first global civilian networks (sic) developed among cooperative capitalists, not among competitive socialists. The capitalists behaved like socialists, and the socialists behaved like capitalists. “ [4] The capitalists in this formulation are merely individualists, who, to Peters’ mind, surprisingly cooperated to build the network. The socialists, in his formulation, are altruists who couldn’t live up to their principles, competing with each other for resources like professors in a badly run faculty. Peters unfortunately appears not sufficiently interested in either socialism or capitalism to nuance these historically heavily-laden terms.

The utopian project, imagined by the Soviet cyberneticists for the USSR and exemplified in the Cybersyn project in Chile, was that a socialist society could manage the entirety of national production distribution and disposal more efficiently and effectively through an internally transparent communication system. Cybersyn was, however, no prototypical Internet. Such a network as Cybersyn would also likely have to be highly secure (since national security would depend on it) and the data exchanged there only selectively available to an exclusive few. Thus, such a system would not likely have produced the vibrant media environment of the Internet we know today.

Peters does not technically imagine how such alternative forms of networked computation might work. Instead he consistently returns to the vague claim that the USSR was too ideologically conflicted, flawed and corrupt to allow the flourishing of the genius of figures like Glushkov to permit the panacea of an Internet-like network to be developed there. “The history of the OGAS project is akin to the history of a miscarried effort to perform an IT upgrade for the corrupt corporation that was the USSR itself.” [5] And cloaks his disparaging attitude in befuddling doubletalk. “The Soviet network projects did not fail because they did not possess the engines of a particular Western political or technological values. They broke down for their own reasons.” [6]

What reasons? They broke down because there could be no Internet in the Soviet Union.

The book points out that the difference that created the conditions for the development of a civilian network such as the Internet was the fact that the US had a private sector which could fund research and production independent of central governmental approval. Curiously, Peters’ gives the example of Paul Baran, inventor of the packet-switching technology essential for the Internet as we know it today, who, seeing his projects disregarded by the priorities of the military industrial complex at the time, eventually abandoned it, only to see it implemented in the US after the British Post system’s research generated the same idea. Here we have two “socialist” government-funded communication projects in “capitalist” competition, apparently the secret to the technical success of the Internet.

A Soviet civilian network, equivalent to that of the nascent Internet in the US, would have meant a network of scientific/academic institutions working outside the classified military information-sphere. There was no such “civilian” sphere. What Peters shows instead is that many of the efforts to implement a national computer network outside of the military were reformist, intending to ‘liberalize’ the Soviet economy and make it more compatible with the capitalist West. “Most of the new employees [of Glushkov’s state-of-the-art cybernetics institute CEMI] were young researchers with bold ambitions and a distaste for the culture of totalitarian control in the 1940s and 1950s. Enthusiasm for decentralized economic reform met with central flows of funding”. [7] Glushkov’s senior ally in the bureaucracy Vasily Nemchinov “sought to impose ‘economic cybernetics’ and its plausibly nonsocialist “dynamic models of balancing capital investment” in the ideologically most acceptable light”. [8]

Peters points out that the USSR’s ideals of social egalitarianism were superimposed on a society which was not used to such a distribution. It is often argued, that, unlike Germany (which Marx & Engels had in mind when they wrote their Manifesto) pre-industrial Russia was lacking the institutional, industrial and economic basis for socialism. The result was that the highly abstract egalitarianism of socialism clashed with the conditions on the ground there, and generated more contradiction, inefficiencies and strife.

The promise of socialism, though it is unprecedented, is that a fairer juster society for every inhabitant of the earth can be achieved. The contradictions between the ideal and the reality need to be allowed to run their course, but this time was not afforded the USSR, as it was not afforded Chile, Cuba, Venezuela, Congo or any other nation which have dared strive for an egalitarian society. Lenin, Allende, Castro, Chavez, Lumumba came to power through popular and democratic processes but were attacked mercilessly, undermined, even assassinated by intolerant reactionary alliances from without and within. Remember that minerals from the de-liberated Congo [9], fundamental to networked computing today, are extracted under the most extreme injustice and exploitative coercion.

Peters claims the the US “succeeded in “networking a nation” because its ethos is to ask “how“ rather than “why”, and that the USSR failed because they were too concerned with “why.” The inertia of systemic unfairness socialism has to confront is immense, and, since it must deliver on its promise to improve the living conditions of the great majority, it is understandable that considerations of “why” will slow down technological choices on a national or global scale. The US and Western economies under their influence had much less of such moral compunctions. Capitalism “frees” entrepreneurs to scale ideas up to industrial scale and ‘externalises’ any deleterious consequences. Today in the age of automated techno-industrial-powered environmental degradation, resource wars and climate change, it appears far too late anymore to ask “why.” Networked capitalism has long had the answer to “how”, though: more computers.

It seems Peters wants to say with this book that socialism can be good as long as it takes place within capitalism. But since Peters’ conflates capitalism with individualism he does not see that this would mean socialist practices merely serving their conventional function as unquantified subordinate contributions to rationalizing capitalist exploitation. When Peters writes that the US built the Internet because their capitalists behaved like socialists, he is merely indicating that socialist practices are a well-spring of the value extracted by capital. Marianna Mazzucato argues convincingly how public investment in fundamental education, technologies and infrastructure brought about the great prosperity (such that it is) and unprecedented cultural affordances such was we enjoy through the Internet. [10] Socialists build things for use value, capitalists build things for surplus value. The huge edifice of Internet-based and coordinated commerce is build on functionalities built in the public interest, not to mention the house of cards ponzi scheme of contemporary financialized capital. The grand juggernaut of US capitalism is still running on infrastructure built during its brief social democratic experiment in the 1950s, which itself was a concession to labour in order to ward off nascent communism at home.

Jeremy Corbyn aims to produce a surge of public investment in vital infrastructure, which, in the proceeding decades it can be assumed, will be reappropriated piece by piece by capital. Public spending on public services do not produce merely quantifiable benefits for “stakeholders”; they produce qualitative improvements which cannot be reduced to commodities, and therefore do not require computer networks to manage or employ, but on which we nevertheless all depend for our social lives.

It is fashionable today to envisage that we are heading, or should head towards a sort of “Fully Automated Luxury Communism” (FALC), where an Internet of Things, transparently managed through a hive-mind, public-access liquid-democracy interface, a civic HyperCyberSyn, will provide unprecedented industrial efficiency and irrepressible prosperity, automatically for all. History shows however that such a system would be set upon and usurped by powerful alliances, just as has every technology in the history of humanity, for the benefit of the few and the detriment of the many. In the meantime, instead of FALC, we get Opportunistically Accelerated Predatory Rentierism, cyborg capital serving a persistent fully-automated financialized rent extraction system.

Peters attempts to close the book on a conciliatory note. “Neither American-style capitalism nor Soviet-style socialism should be considered a sufficient philosophical banner for making our way into a networked world… The social necessity of restraining self-interested competition unites, not divides, the modern legacy of cold-war capitalism.” [12] Peters’ appears to propose that capitalists (in his taxonomy) are the true socialists since they acknowledge the limits of their self-interest whereas socialists are dangerous because they must pretend as if self-interest doesn’t exist. But what can the benefit of this caricature conciliation of socialism and capitalism be? Only if we can mutualize the rentier system for the benefit of all according to their needs will we generate societies of sustainable social and economic justice worth the name communism, with all the myriad revolutionary technological affordances we can barely imagine today.

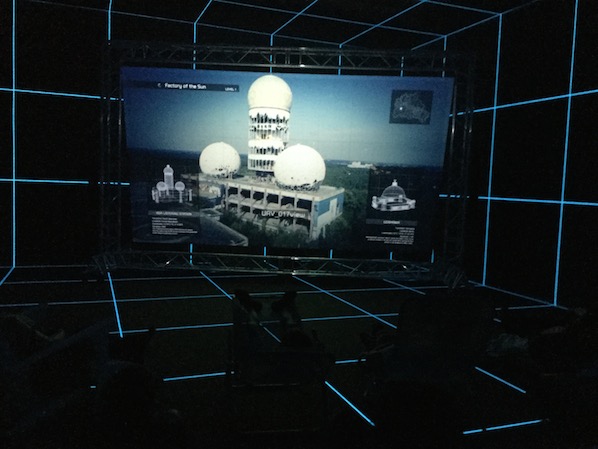

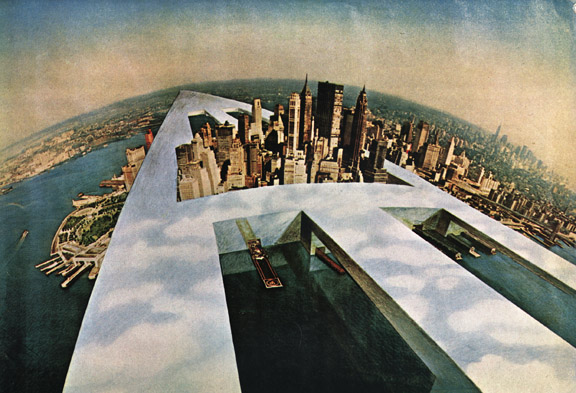

The exhibition Power and Architecture was created for viewing across several months in a particular sequence. Part 1 focused on Utopia and Modernity (12 June – 3 July), Part 2 on Dead spaces and Ruins, (July 4 – August 10), Part 3 on Citizen activated space — Museum of Skateboarding,(11 August – 11 September), and Part 4 on The afterlives of Modernity — shared values and routines, (15 September – 9 October). A conference held in June – The Centre Cannot Hold? –led by important scholars Michał Murawski (SSEES, UCL) and Jonathan Bach (New School, New York) served to frame the cultural, political, economic ramifications of “centrality and monumentality in 20th century cities” with thought from prominent researchers, architects and artists. Power and Architecture concluded this October as the Calvert 22 Foundation partners with innovative architecture, design and engineering collectives Assemble (UK), Museum of Architecture (UK) and reSITE (CZ) and an Urban Research Mobility Lab connects London with Prague by asking the question: how does migration and mobility in cities affect the experience of the urban environment? A curated series of reports, essays and photo stories further explored the themes of Power and Architecture in the online Calvert Journal available through the gallery website.

Calvert 22 is a gallery devoted to contemporary Eastern European and Russian art. They presented this exhibition as “a season on utopian public space and the quest for new national identities across the post-Soviet world.” I arrived at the gallery, a Californian artist, coincidentally just as I’d read comments from Lev Manovich about the young intelligensia of post-Soviet Russia. Thus, when thinking about the exhibition, I was also thinking about the new global mobile class and the impact of Putin’s Russia upon a new generation.

Power and Architecture is a fascinating collection of research into contemporary art, films, and research about post-Soviet urban identity and the positioning of artists therein. Obviously once communist societies have experienced dramatic change since the fall of the Berlin Wall, collapse of Soviet Russia, and rise of Putin to power. Curators used multiple cultural lenses with which to pry open a critical “western” eye on the aftermath of the Soviet era and invited exploration of cultural narratives about the “post-Soviet” city. The exhibit, particularly in certain places, looked at ideas which appear to have disappeared or become outmoded as a means of aesthetic and political communication. There was an air of longing and self-reflection towards Russian identity when experiencing the work. The Russian people have something to reckon with; a revolutionary utopia which once was, but which is no more and which has left them with the traces of an almost empire,- although to call communist Russian an empire seems to obscure the politics of the revolutionary element-. These juxtapositions were in essence the heart of the show which explored the Soviet Union as constructed space. This ”location” then functions as a backdrop to present-day national identity and urban design emerges in the portrait of a “post-Soviet” society with its own futuristic ideas as well as in the lingering relics of Soviet intentions.

Power and Architecture falls on the heels of Calvert 22’s very successful Red Africa program which examined the cultural, economic and social geography between Africa, Eastern Europe, Russia and related countries during the Cold War. The Eastern European art historical and social trend of the last thirty years labelled ‘self-historicization’ –or the self-conscious effort for Eastern European and Russian artists to articulate, archive, and collect their own history, is exercised throughout the exhibit itself designed in series of presentations directed at the problem of “historical understanding” of history. The post-Soviet city and utopian public space was used as a critical framework from which to position contemporary space, identity and the intent of the exhibiting artists. The Soviet Union has fallen, but who or how is its revising and re-examination taking place?

Part 2 which dealt with “dead spaces”, the architectural ruins of empty cities, military bases, technologial infrastructure and cavernous, open landscapes at once modern and moribund seemed to suggest that retrospective analysis of utopia could only be a well-conceived guess at what was or might have been. This Part was a sojourn into the life of Soviet artifacts both remaindered in their historical trajectory and as a convincing backdrop to a pervasive contemporary ambivalence. Danila Tkachenko’s “Restricted Areas” for instance, was a series of photographs documenting relics of the military build up of the Soviet Union only to be found on abandoned, snow-covered sites in the frozen tundra. Oversized photographs of personal ID cards from unknown persons presumably found amidst Soviet architectural rubble, large format, richly-detailed color photographs of crumbling rooms, weather-worn, orphaned Soviet-era paintings, and peeling, once colorful murals inside Soviet military bases and institutions form an historic record of obvious and shocking lack of preservation of Soviet art and architecture as Russian history. Artists participating in Dead spaces and ruins were Vahram Aghasyan, Anton Ginzburg, and Eric Lusito.

To say that this work engaged narratives which imbue modern mythologies of “utopia” with certain ideas, or contained evidence of the self-conscious effort to bring post-Soviet identity into the picture is an understatement. ‘Utopian’ ideas’ exhibited, situated in urbanism and public space, were the self-conscious investigation of old or familiar‘ or “statist” (maybe) viewpoints on public identity and gave curious attention to questions of truth, experience, voice and historic preservation found in documentary discourse. Self-historicization was apparent in Russian artist Kirill Savchenkov’s Museum of Skateboarding, a mixed media installation, which was its own entire Part 3. Savchenkov’s piece talked about the activation of public space by young people and about skateboarding as a means through which to reflect upon the post-Soviet residential suburbs of Moscow. This work suggests how certain architectural interventions or objects contain meaning and can even be accessed differently or more significantly through subculture. It alluded to tropes in notions of “world” or global “utopia” which translate across seemingly disparate spaces and identities such as Californian and post-Soviet/Soviet Russia. Moreover, this reading of public space as accessed and interpreted by youth is a powerful concept about notions of history and who it belongs to.

In Part 4 (on through Oct. 9) the urban poetics of the post-Soviet city are further contextualized by looking more closely at modernity and everyday life. The afterlives of Modernity — shared values and routines. This Part concluded the exhibit with four artists, Aikaterini Gegisian, Donald Weber, Dmytrij Wulffius, and Ogino Knauss, who examine the “afterlife” of the utopian endeavor, especially the search for new national identity. This theme is provocative to be sure, given the current political contest in the Ukraine and Russia’s role in Syrian conflicts. The curators write:

“Across the former Soviet Union there are a series of architectural and physical nostalgias connecting citizens who share the same socialist history – Part 4 of the programme reflects on these shared values and routines for citizens today.”

I asked myself the question—how does art tie societies together through processes of change? Aikaterini Gegesian’s film, “My Pink City” offers a portrait of a post-Soviet Yeravan in transition and depicts the militarisation of public space and the gendered divisions within the city. In many instances, Russian government has pushed for laws “designed to rid Ukraine’s public spaces of communist relics. Their destruction proclaims a deep desire to change the cultural narrative.” In Part 2 many documentary photographs of “dead” Soviet relics are a poignant record, and politically at odds with ideas at play in contemporary Russian national consciousness. It is a record which rightfully belongs to the Russian and Ukrainian people and which makes this show more meaningful when thought of as the struggle to preserve the past for the future.“Monumental Propaganda”, a series by Donald Weber documenting sites where Soviet monuments stood and the empty pedestals remain, speaks to exactly this. Dmytrij Wulffius’ “Traces on Concrete” is a series of photographs taken from 2009 and 2013 of his own hometown, Yalta in Crimea, which also explore its architectural landscape from the perspective of modern youth. “Re:centering Periphery: Post Socialist Triplicities” by Ogino Knauss is a fascinating examination of post-socialist history in Berlin, Belgrade, and Moscow, three cities in which modernity triggered profound utopianism towards the “radical transformation of the everyday.” The piece looks at “what is left of the architectural vision in the cities and what this legacy leaves to citizens”.

Power and Architecture aimed at a present-day coming to terms with a particular Russian existence now broken into segments and pieces. It focused profoundly on the precarity and erasure of history which plagues 21st century thought on so many levels.The real and the fake, the true and false, the meanings of “Soviet utopian vision” and its presence in time in architectural and artistic form. Without quite melding together as what that vision was in the political sense, the show formed a quasi-science fictional narrative and interpretation; a history of place, both real and imagined; promised and denied.

Central to the visual collection and comprehension of these ideas was, curiously, the strategy of the archive where the act of collection takes place and where the borders and edges of history are possible. By focusing upon the urban environment of the Soviet Union now past, Power and Architecture asked us to consider ‘what modernity is” in this context. If it is machine aesthetics as James Bridle (2011) suggests, then which machines have contributed and how do we use this modern aesthetic position on technology to examine a past? If it is the new aesthetic to be looking at old relics with a different lens, then what intellectual “spin” is constructed? For whom, how, and for what? Maybe modernity is all of these—a presence of unprecedented scale in terms of cities, and the sky and the water. How do we see this totality now? How did they see it then?

Modernity did come upon Eastern Europe and Russia, arguably in similar and dissimilar ways to how it was absorbed in the west. Power and Architecture re-examined the Soviet epoch, through what artists are seeing and thinking about what has remained. It seemed expressed as a brute emergence of a set of ideas which, because they were collective, revolutionary, technological, shaped and still shape Russian consciousness, but as a past. How the past is preserved or ingested is again a compelling idea on the power-struggles for “history” which take place in modern times. Power and Architecture elucidated key features of this new era of global subjectivity and societal change through creative lenses of the recent past.

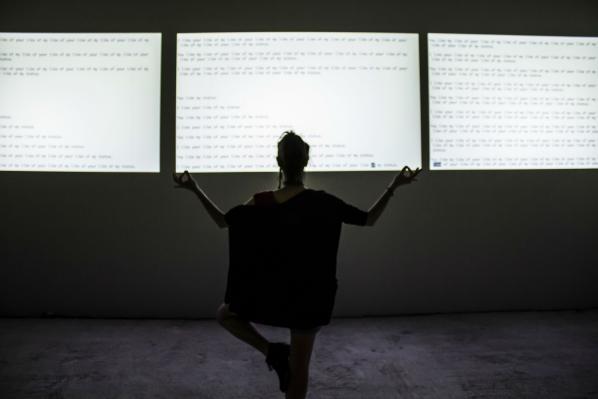

When looking at the many artistic projects focused on how and why we use the internet, it’s easy to find yourself lost in a field which doesn’t show obvious, strong ties with what we normally know as “traditional art history”. This is due to historical and social reasons that emerged between the 80s, 90s and early 2000. These artists were at the vanguard of art culture and pushed at the edges of what art could be, whilst living in a post-punk and postmodernist era, and on tip of this, the arrival of the Internet in 94 changed everything. Many artists took on the challenge of what the Internet offered the world creatively, and explored it not merely as a marketing tool or a place to upload images and videos, but as a medium in its own right, inventing new technically informed, artistic tools and also building grass root led, networked art groups with new infrastructures as cultural platforms. Turning away from anything relating to the mainstream art world and what was seen as outmoded and tired traditions.

In the last decade, we’ve seen the expansion of the Internet and its use by younger generations where the medium is no longer something you exploit to change the culture, but more to integrate in traditional terms, canonical contexts.However, artist Jan Robert Leegte (born in 1973) is a very important figure to reflect upon, in order to understand this transition; while other artists of his generation were taking the internet for a non-hierarchical distributed system, he chose to explore it from a classical studies background that forged the cardinal points of his artistic research. He reflects an Internet art influenced practice which not only exists online but also in physical space. In fact, we can safely say he can be considered as one of the first Post-Internet artists. This makes him a pivotal figure in this historical segment and it’s under this light that one must visit the online exhibition On Digital Materiality (Carroll / Fletcher Onscreen, 3 August-12 September 2016). It’s a retrospective show presenting some of the most important and representative works of the Dutch artist, who wrote for the occasion an essay in which describes some of the most important aspects of his work.

Leegte says, the “materials I first used were basic HTML objects, buttons, scrollbars, frame borders, table borders, and also plain color fields and found images. I questioned what it was that rendered this practice similar to making installations rather than collages. At first it was the simulacrum of real world interactive elements (buttons, window frames, etc.). The operating system extended this haptic strategy with traditional paper-based forms, like check boxes, text fields, lists, etc, and, along with the form elements and the interactive document, led to an ecosystem of fake 3D, interactive objects.”

The work fluctuates between working on the surface and thinking in three dimensions. The same difference can be found with his use of Photoshop and HTML. If in the former case an image editing software operates directly on the final result, for the latter there is the need to know how to write code while at the same time imagine what the potential results will bring via its translation in the public space, the internet. In this sense, we do not hesitate to define Leegte as an artist who studies and uses the tools of the sculptor; he wonders how to place objects in the space, he feels the problem of contextualising a work in relation to a public and physical environment.

The perception of a substantial difference between surface and space is also proven with his interest in the basic elements of composing the digital interface (scrollbars, mouse pointers, etc). His research examines the artificial environment built by Microsoft and Apple designers. The colours and the shapes were designed to not be perceived as evident mediating agents between the user and the content – in this sense, it is interesting to note that Microsoft has often chosen a minimalist style (shades of grey, square shapes) while with Apple systems the style is usually more exuberant.

However, we should not look at the former as a less culturally relevant product. In the same way, we should not take the white cube exhibition space as a synonym of neutrality (unless we want to think that the whiteness and emptiness stay for an objectivity). This is an aspect that the artist does not seem to detect (in the text, he writes that he “preferred the aesthetics of the Windows classic interface design because of its minimalistic design – no rounded corners and ribbings like the OS 9 design, but simple beveled grey rectangles and a button object was merely a highlight and a shadow, nothing more”).

The artist reflected on how specific design elements may in some sense be preserved, as reflections and products of a particular aesthetic and cultural taste: “In Memory of New Materials Gone” (2014) is a work made by a print of the OS9 scrollbar placed in a transparent case in the same way you would do with an object no longer fashionable. This project and all the other works belonging to The Scrollbar Composition Series programmatically address the perception of virtually anonymous and transparent objects on the screen in a three-dimensional space. In a situation where their significance must be noticed; it’s the artist himself who begs to not see in this a disruptive act, an action that reveals the subtle ways in which they influence us. It is, however (but not “in opposition to”), a reflection on the artist’s activity; as we previously noted, these works are shown on the internet in the same manner in which they would be set up in a gallery space.

Perhaps, the highest point of the artist’s reflection on the differences you meet working on a surface or in three dimensions is The Photoshop Marquee Selection Series. “Random Selection in Random Image” (2012), in which a randomly generated selection marquee is shown within an image randomly obtained from the net. It is the most important work of this series because it opens three-dimensional gaps which have been created sculpturally in two-dimensional images – a dynamic that has echoes of “Scrollbar Composition” (2000), in which the Web browser’s monodimensional space is broken down and reassembled in many windows, many independent spaces sharing only the mathematical material they are made of.

The works featured in this exhibition are related to questions that go beyond the historical and cultural contingency in which they have been created. This makes many of them feel very much alive even 20 years after their creation (a novelty in digital art, I would say). This allows a healthy dialogue between different generations of artists to exist as common ground. It also engages art experts who want to be introduced to artistic issues linked to the internet. It is a dynamic that makes this exhibition a special opportunity for us all to relook at this so-called digital culture and its traditional and non-traditional art theories and its practice under a peculiar and exciting light.

On Digital Materiality – an Internet exhibition is online at Carroll / Fletcher Onscreen until 12 September 2016

What is the relationship between state corruption and economic collapse in Greece?

Lina Theodorou, artist and creator of the board game ‘Pawnshop- Days of Mistrust’, talks with Furtherfield’s Ruth Catlow about Grexit, Brexit and crisis in Europe.

I met Lina Theodorou, the artist and creator of Pawnshop, in her apartment on a sunny Sunday morning in Berlin. It was just one week after the UK referendum resulted in a vote to leave the EU. I was in Berlin to take part in an event called Art, Money & Self Organization in Digital Capitalism, the first in a series of events called Arts and Commons, organised by Supermarkt.

Theodorou and I quickly got onto the topic of Brexit. We compared notes. She wondered if, like Greece, the UK government would choose to ignore the result of the referendum, fail to invoke Article 50, and stay in Europe after all. That possibility had not occurred to me. She talked about her memories surrounding the Grexit debate- the distress, the uncertainty, the shocking hatred and hostility expressed between family members and people previously considered friends. I had been deeply shaken by the upsurge of street-level racism on the streets of Britain.

Pawnshop, the artwork that is also a board game, was set up for play, laid out on a table in her studio. It is an inversion of Monopoly: the same square board, the pieces, the bank, the cards, the dice. However in this game the player starts the game with no money, only property – jewelery, a bouzouki, antique furniture, a flat- and pays a European tax of €1500 when they pass Go (if they get that far).

Players proceed around the board, according to the luck of the dice, along a path strewn with dilemmas. A second row of squares is used to keep track of the time spent dealing with the consequences of their choices- jail sentences, or hospitalizations for example. As they move around the board, they pick one of the cards, depending on their landing square, and must choose how they will respond to the given dilemmas.

Theodorou tells me that the game is based entirely in fact. For years she has collected newspaper stories in Greece. And here they are gathered in four categories of cards – Dilemma, Involvement, Debt and Luck- to encapsulate the experience of daily life, for everyone, in modern day Greece. ”If you are honest you lose” she says.