Parrots. Grey parrots. African grey parrots. African grey parrots laughing. I hear African grey parrots laughing. I hear African grey parrots laughing and it’s weird.

Their laughter sounds forced. Not compulsive, no, it’s not that. But artificial to say the least. Somewhat robotic. And I find it rather disturbing.

I can also hear birds chirping outside, and their sound is clearly different. Their tone of voice is lively and high pitched. And it brings me joy, almost subconsciously.

However, as I begin to doubt the authenticity of the African grey parrots’ laughter, I am told that their laughter is real. They are real parrots that are truly emitting the sound of laughter: they have been trained to do so.

The history of the process that leads me to listen to this laughter spans over a period of sixteen years. Sixteen years during which the Slovenian artist Sanela Jahić has produced works that have reversed the power balance in the world of work (Five Handshakes, 2016), explored the range of emotions within the human-machine relations in industrial workplaces, (The Factory, 2013), studied the history of gesture efficiency in factories (Tempo Tempo, 2014) and created the conditions for experiencing human-machine co-creation (Fire Painting, 2010). However, over the past three years she narrowed her focus to applying automation to her own practice. Since these prosthetic technologies pervade the capitalist world of work—through the increasing replacement of workforce by industrial robotic arms and systems as well as through the increasingly algorithmic management of workers—why should it not be applied to the production of artworks? A seemingly light-hearted question that allows the artist to raise another, deeper question: can artistic creation be considered on the same level as other types of work? And ultimately, what does it mean to cast off the burden of choice to machines, what does it mean to try to distance oneself from one’s subjectivity while consciously choosing to delegate one’s decisions to a computer program?

Responding to generalized quantophrenia1—from permanent, automatized and unsuspected data extraction to voluntary submission to the fascinating and oxymoronic idea of the quantified self, i.e. a human being reduced to mere numbers—Sanela Jahić started to conceive a way to turn her career into numbers. She created a classification system which she applied to all of her artworks and through this produced a database of her works. A selection of parameters described as keywords represented numerous different aspects of her work such as ‘manual labour’, ‘mathematical precision’, ‘mechanical device for showing images’, ‘collaboration’, ‘mistake as a sign of the human factor’, ‘revealing patterns’, ‘mechanism in the back’, ‘machine painting’, ‘light-based medium’, and many more; their intensity was displayed in graph form in a series of works titled The Labour of Making Labour Disappear (2018). But this would not present sufficient data for an algorithm to create a work on Jahić’s behalf, since this new work would have been based merely on the previously created works, and not on what would have actually taken place in the artist’s mind at the moment of creation.

In order to overcome the potentially simplistic predictive outcome, Jahić decided to complete the database with elements that would have probably influenced her. Thus, she added approximately six months of real time data on what she was reading while working on this project to the parameters. Every word from every text that passed in front of her eyes increased the database, opening new horizons of thought. With this amount of technical, theoretical, sociological and descriptive terms, ranked by the frequency of their occurrences, the algorithm was set to act as a surrogate of her creative endeavour.

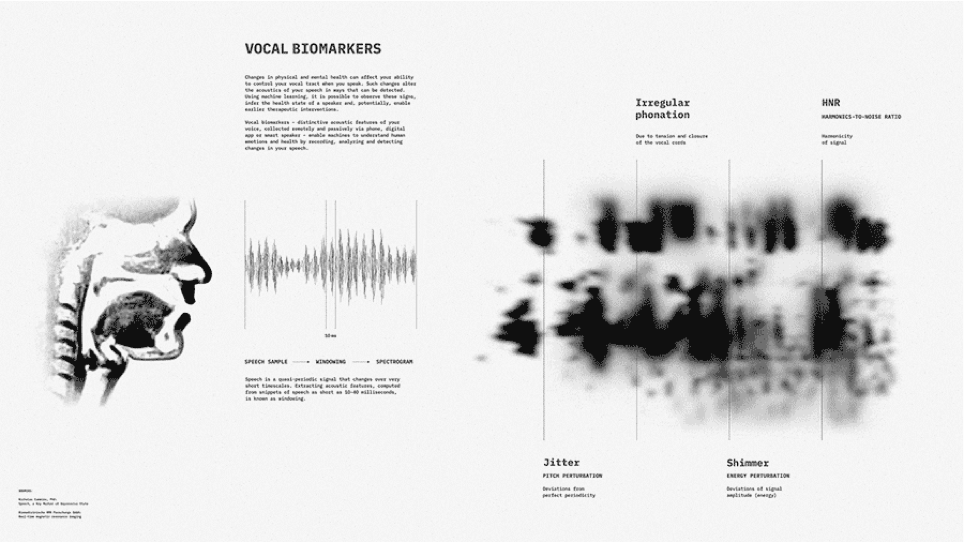

According to the artist, if we consider this process as a (psycho)analysis of her work, we can also ironically read it as an analysis of the prediction algorithm by itself. Indeed, the algorithm specifically designed2 for the occasion, produced output terms such as: ‘behavioural data’, ‘tracking devices’, ‘scientific investigation’, ‘assessment tool’ and ‘machine learning’. ‘Vocal biomarkers’ also came up. Vocal biomarkers are a diagnostic tool used by artificial intelligence systems that scan for voice patterns in speech with the aim of detecting diseases such as depression, cancer, or heart conditions with the aid of a database of intonations linked to predetermined underlying emotions. This speech signal analysis focuses on the tone of voice and therefore does not require the spoken words to be numerous or even to make sense, which is why individual words can be used as vocal exercises that provide the necessary data.

Pataka is one of these words. Found in the Mapuche language in which it means a hundred, as well as in Hindi where it designates firecrackers, the word Pataka, when pronounced, asks the speaker to emit rapidly alternating sounds which allow for precise detection of their muscle control, the lack of which is a common sign of depression.

Since Sanela Jahić had to interpret the predictive results from the algorithm in order to turn them into an artwork in its own right, she chose to work around the use of this specific word3 but not to work with people afflicted by illness; thus she decided to use parrots as proxies. Parrots are known for imitating the voice of the persons teaching them to speak, and this can be seen in Jahić’s Pataka videos. Parrots. Grey parrots. African grey parrots. African grey parrots talking. And African grey parrots laughing.

Sanela Jahić, Uncertainty-in-the-Loop, Aksioma, Ljubljana, 23 September – 23 October 2020, and Delta Lab, Rijeka, 5–27 November 2020.

On September 25, 2020, the Disruption Network Lab opened its 20th conference “Data Cities: Smart Technologies, Tracking & Human Rights” curated by Tatiana Bazzichelli, founder and program director of the organisation, and Mauro Mondello, investigative journalist and filmmaker. The two-day-event was a journey inside smart-city visions of the future, reflecting on technologies that significantly impact billions of citizens’ lives and enshrine new unprecedented concentrations of power, characterising the era of surveillance capitalism. A digital future which is already here.

Smart urbanism relies on algorithms, data mining, analytics, machine learning and infrastructures, providing scientists and engineers with the capability of extracting value from the city and its people, whose lives and bodies are commodified. The adjective ‘smart’ represents a marketing gimmick used to boost brands and commercial products. When employed to designate metropolitan areas, it describes cities which are liveable, sustainable and efficient thanks to technology and the Internet.

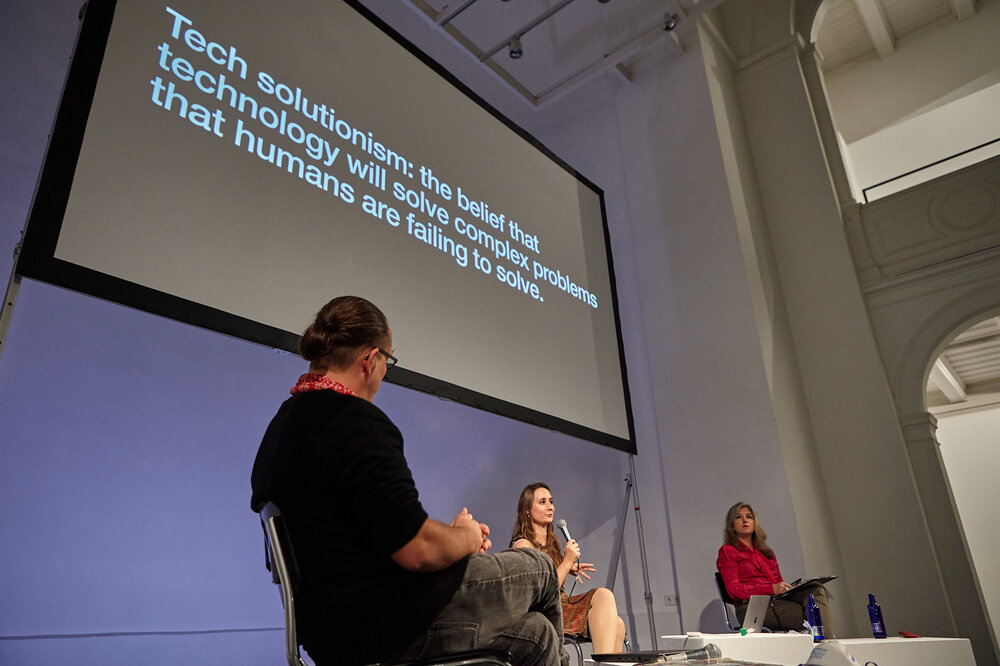

The conference was held at Berlin’s Kunstquartier Bethanien and brought together researchers, activists and artists to discuss what kind of technologies are transforming metropolises and how. The Disruption Network Lab aimed at stimulating a concrete debate, devoid of the rhetoric of solutionism, in which participants could focus on the socio-political implications of algorithmic sovereignty and the negative consequences on fundamental rights of tracking, surveillance and AI. They shared the results of their latest work and proposed a critical approach, based on the motivation of transforming mere opposition into a concrete path for inspirational change.

The first part of the opening keynote “Reclaiming Data Cities: Fighting for the Future We Really Want” was delivered by Denis “Jaromil” Roio, ethical hacker, artist and activist. In his talk, moderated by Daniel Irrgang, research fellow at the Weizenbaum Institute for the Networked Society, Jaromil focused on algorithmic sovereignty and the incapacity to govern technological transformation which characterises our societies today.

Jaromil looked at increasing investments in AI, robots and machine learning, acknowledging that automated decision-making informed by algorithms has become a dominant reality extending to almost all aspects of life. From the code running on thousands of e-devices to the titanic ICTs-infrastructures connecting us, when we think about the technology surrounding us, we realise that we have no proper control over it. Even at home, we cannot fully know what the algorithms animating our own devices are adopted for, if they make us understand the world better or if they are instead designed to allow machines to study and extract data from us for the benefit of their creators. The same critical issues and doubts emerge with a large-scale implementation of tech within so-called “smart cities”, maximization of the “Internet of Things” born in the 1980s.

Personal data is a lucrative commodity and big data means profit, power, and insights, which is essential to all government agencies and tech firms. Jaromil announced a call-to-action for hackers and programmers, to get involved without compromise and play a key role in building urban projects which will safeguard the rights of those living in them, taking into consideration that by 2050, an estimated 70 per cent of the world’s population may well live in cities.

Jaromil observed that there is too often a tremendous difference between what we see when we look at a machine and what really happens inside it. Since the dawn of the first hacking communities, hackers preferred writing their own software and constructing their own machines. They were free to disassemble and reassemble them, having control over all the functions and direct access to the source code. This was also a way to be independent from the corporate world and authorities, which they mistrusted.

Today, users are mostly unaware of the potential of their own tech-devices, which are no longer oriented strictly towards serving them. They have no exposure to programming and think Computer Science and Informatics are way too difficult to learn, and so entrust themselves entirely to governments and tech firms. Jaromil works to simplify interface and programming language, so people can learn how to program and regain control over their tech. He supports minimalism in software design and a process of democratisation of programming languages which works against technocratic monopolies. His Think & Do Tank—Dyne.org—is a non-profit software house with expertise in social and technical innovation, gathering developers from all over the world. It integrates art, science and technology in brilliant community-oriented projects (D-CENT, DECODE, Commonfare, Devuan), promoting decentralisation and digital sovereignty to encourage empowerment for the people.

The second keynote speaker, Julia Koiber, managing director at SuperrrLab, addressed issues of technology for the common good, open data and transparency, and—like the previous speaker—reflected on uncontrolled technological transformation. Koiber noticed that the more people are mobilising to be decision-makers, rather than passive data providers, the more they see how difficult it is to ensure that publicly relevant data remains subject to transparent control and public ownership. In the EU several voices are pushing for solutions, including anonymised user data to be classified as ‘common good’ and therefore free from the control of tech companies.

Recalling the recent Canadian experience of Sidewalk Labs (Alphabet Inc.’s company for urban tech development), Koiber explained that in order to re-imagine the future of neighbourhoods and cities, it is necessary to involve local communities. The Google’s company had proposed rebuilding an area in east Toronto, turning it into its first smart city: an eco-friendly digitised and technological urban planning project, constantly collecting data to achieve perfect city living, and a prototype for Google’ similar developments worldwide. In pushing back against the plan and its vertical approach, the municipality of Toronto made clear that it was not ready to consider the project unless it was developed firmly under public control. The smart city development which never really started died out with the onset of the COVID-19 crisis. Its detractors argue that city dwellers were meant to be human sensors collecting data to test new tech-solutions and increase corporate profit. Data collected during the provision of public services and administrative data should be public; it belongs to the people, not to a black box company.

As Jaromil and Koiber discussed, in the main capitals of the world the debate on algorithmic sovereignty is open and initiatives such as the “Manifesto in favour of technological sovereignty and digital rights for cities,” written in Barcelona, reflect the belief that it will be crucial for cities to achieve full control and autonomy of their ICTs, which includes service infrastructures, websites, applications and data owned by the cities themselves and regulated by laws protecting the interests and fundamental rights of their citizens. Their implementation shall come within people-centric projects and a transparent participatory process.

The work of the conference continued with the panel “Making Cities Smart for Us: Subverting Tracking & Surveillance,” a cross-section of projects by activists, researchers and artists digging into the false myth of safe and neutral technologies, proposing both counterstrategies and solutions to tackle issues introduced in the opening keynote.

Eva Blum-Dumontet, English researcher on privacy and social-economic rights, dedicated her work to the impact of tech on people, particularly those in vulnerable situations. She opened the talk with the observation that the term ‘smart city’ lacks of an official definition; it was coined by IBM’s marketing team in 2005 without a scientific basis. Since then, tech firms from all over the world have been developing projects to get into governments’ favour and to build urban areas that integrate boundless tech-solutions: security and surveillance, energy and mobility, construction and housing, water supply systems and so on.

As of today, thanks to smart cities, companies such as IBM, Cisco, Huawei, Microsoft and Siemens have found a way to generate the satisfaction of both governments and their suppliers, but do not seem to act in the public’s best interest. In their vision of smart urbanism people are only resources: like water, buildings and administrative services, they are something to extract value from.

Blum-Dumontet explained that when we refer to urban tech-development, we need to remember that cities are political spaces and that technology is not objective. Cities are a concentration of countless socio-economic obstacles that prevent many individuals from living a dignified life. Privilege, bias, racism and sexism are already integrated in our cities´ (tech-)infrastructures. The researcher acknowledged that it is very important to implement people-centric solutions, while keeping in mind that as of now our cities are neither inclusive nor built for all, with typical exclusion of, for instance, differently abled individuals, low-income residents and genderqueer people.

A sharp critique of the socio-economic systems causing injustice, exploitation and criminalisation, also lies at the core River Honer’s work. River is a web developer at Expedition Grundeinkommen and anti-capitalist tech activist, who wants to support citizens and activists in their struggle for radical transformation toward more just cities and societies without relying on solutions provided by governments and corporations.

Her work methodology includes critical mapping and geospatial analyses, in order to visualise and find solutions to structurally unjust distribution of services, access and opportunities in given geographic areas. Honer works with multidisciplinary teams on community-based data gathering, and turns information into geo-visualisation to address social issues and disrupt systems of discriminatory practices which target minorities and individuals. Examples of her work include LightPath, an app providing the safest well-lit walking route between two locations through various cities; Refuge Restroom, which displays safe restroom access for transgender, intersex, and gender nonconforming individuals who suffer violence and criminalisation in the city, and the recent COVID-19 tenant protection map.

Honer’s projects are developed to find practical solutions to systematic problems which underpin a ruthless political-economic structure. She works on tech that ignores or undermines the interests of capitalism and facilitates organisation for the public ownership of housing, utilities, transport, and means of production.

The Disruption Network Lab dedicated a workshop to her Avoid Control Project, a subversive tracking and alert system that Honer developed to collect the location of ticket controllers for the Berlin public transportation company BVG, whose methods are widely considered aggressive and discriminatory.

There are many cities in the world in which activist groups, non-governmental organisations and political parties advocate for a complete revocation of fares on public transport systems. The topic has been debated for many years in Berlin too; the BVG is a public for-profit company earning millions of euros annually on advertising alone, and in addition charges expensive flat fares for all travelers.

The panel discussion was concluded with Norway-based speakers Linda Kronman and Andreas Zingerle of the KairUs collective. The two artists explored topics such as vulnerabilities in Internet-of-Things-devices and corporatisation of city governance in smart cities, as well as giving life to citizen-sensitive-projects in which technology is used to reclaim control of our living environments. As Bazzichelli explained when presenting the project “Suspicious Behaviours” by Kronman, KairUs’s production constitutes an example of digital art eroding the assumptions of objective or neutral Artificial Intelligence, and shows that hidden biases and hidden human decisions influence the detection of suspicious behaviour within systems of surveillance, which determines the social impacts of technology.

The KairUs collective also presented a few of its other projects: “The Internet of Other People’s things” addresses technological transformation of cities and tries to develop new critical perspectives on technology and its impact on peoples’ lifestyles. Their video-installation “Panopticities” and the artistic project “Insecure by Design” (2018) visualise the harmful nature of surveillance capitalism from the unusual perspective of odd vulnerabilities which put controlled and controllers at risk, such as models of CCTV and IP cameras with default login credentials and insecure security systems which are easy to hack or have by default no password-protection at all.

Focusing on the reality of smart cities projects, the collective worked on “Summer Research Lab: U City Sogdo IDB”(2017), which looked at Asian smart urbanism and reminding the panellists that many cities like Singapore, Jakarta, Bangkok, Hanoi, Kuala Lump already heavily rely on tech. In Songdo City, South Korea, the Songdo International Business District (Songdo IBD), is a new “ubiquitous city” built from scratch, where AI can monitor the entire population’s needs and movements. At any moment, through chip-implant bracelets, it is possible to spot where someone is located, or observe people undetected using cameras covering the whole city. Sensors constantly gather information and all services are automatised. There are no discernible waste bins in the park or on street corners; everything seems under tech-control and in order. As the artists explained, this 10-year development project is estimated to cost in excess of 40 billion USD, making it one of the most expensive development projects ever undertaken.

The task of speculative architecture is to create narratives about how new technologies and networks influence and shape spaces and cultures, foreseeing possible futures and imagining how and where new forms of human activity could exist within cities changed by these new processes. Liam Young, film director, designer and speculative architect opened the keynote on the second conference day with his film “Worlds Less Travelled: Mega-Cities, AI & Critical Sci-Fi“. Through small glimpses, fragments and snapshots taken from a series of his films, he portrayed an alternative future of technology and automation in which everything is controlled by tech, where complexities and subcultures are flattened as a result of technology, and people have been relegated to the status of mere customers instead of citizens

Young employs the techniques of popular media, animation, games and doc-making to explore the architectural, urban and cultural implications of new technologies. His work is a means of visualising imaginary future worlds in order to help understand the one we are in now. Critical science fiction provides a counter-narrative to the ordinary way we have of representing time and society. Young speaks of aesthetics, individuals and relationships based on objects that listen and talk back, but which mostly communicate with other machines. He shows us alternative futures of urban architecture, where algorithms define the extant future, and where human scale is no longer the parameter used to measure space and relations.

Young’s production also focused on the Post-Anthropocene, an era in which technology and artificial intelligence order, shape and animate the world, marking the end of human-centered design and the appearance of new typologies of post-human architectures. Ours is a future of data centres, ITCs networks, buildings and infrastructures which are not for people; architectural spaces entirely empty of human lives, with fields managed by industrialised agriculture techniques and self-driving vehicles. Humans are few and isolated, living surrounded by an expanse of server stacks, mobile shelving systems, robotic cranes and vacuum cleaners. The Anthropocene, in which humans are the dominant force shaping the planet, is over.

The keynote, moderated by the journalist Lucia Conti, editor at “Il Mitte”and communication expert at UNIDO, moved from the corporate dystopia of Young, in which tech companies own cities and social network interactions are the only way people interrelate with reality, to the work of filmmaker Tonje Hessen Schei, director of the documentary film “iHuman”(2020). The documentary touches on how things are evolving from biometric surveillance to diversity in data, providing a closer look at how AI and algorithms are employed to influence elections, to structure online opinion manipulation, and to build systems of social control. In doing so, Hessen Schei depicts an unprecedented concentration of power in the hands of few individuals.

The movie also presents the latest developments in Artificial Intelligence and Artificial General Intelligence, the hypothetical intelligence of machines that can understand or learn any task that a human being can.

When considering AI, questions, answers and predictions in its technological development will always reflect the political and socioeconomic point of view, consciously or unconsciously, of its creators. For instance —as described in the Disruption Network Lab´s conference “AI Traps” (2019)—credit scores are historically correlated with racist segregated neighbourhoods. Risk analyses and predictive policing data are also corrupted by racist prejudice leading to biased data collection which reinforces privilege. As a result new technologies are merely replicating old divisions and conflicts. By instituting policies like facial recognition, for instance, we replicate deeply ingrained behaviours based on race and gender stereotypes and mediated by algorithms.

Automated systems are mostly trying to predict and identify a risk, which is defined according to cultural parameters reflecting the historical, social and political milieu, in order to give answers and make decisions which fit a certain point of view. What we are and where we are as a collective —as well as what we have achieved and what we still lack culturally— gets coded directly into software, and determines how those same decisions will be made in the future. Critical problems become obvious in case of neural networks and supervised learning.

Simply put, these are machines which know how to learn and networks which are trained to reproduce a given task by processing examples, making errors and forming probability-weighted associations. The machine learns from its mistakes and adjusts its weighted associations according to a learning rule and using error values. Repeated adjustments eventually allow the neural network to reproduce an output increasingly similar to the original task, until it reaches a precise reproduction. The fact is that algorithmic operations are often unpredictable and difficult to discern, with results that sometimes surprise even their creators. iHuman shows that this new kind of AI can be used to develop dangerous, uncontrollable autonomous weapons that ruthlessly accomplish their tasks with surgical efficiency.

Conti moderated the dialogue between Hessen Schei, Young, and Anna Ramskogler-Witt, artistic director of the Human Rights Film Festival Berlin, digging deeper into aspects such as censorship, social control and surveillance. The panellists reflected on the fact that—far from being an objective construct and the result of logic and math—algorithms are the product of their developers’ socio-economic backgrounds and individual beliefs; they decide what type of data the algorithm will process and to what purpose.

All speakers expressed concern about the fact that the research and development of Artificial Intelligence is ruled by a few highly wealthy individuals and spoiled megalomaniacs from the Silicon Valley, capitalists using their billions to develop machines which are supposed to be ‘smarter’ than human beings. But smart in this context can be a synonym for brutal opportunism: some of the personalities and scientists immortalised in Hessen Schei´s work seem lost in the tiny difference between playing the roles of visionary leaders and those whose vision has started to deteriorate and distort things. Their visions, which encapsulate the technology for smart cities, appear to be far away from people-centric and based on human rights.

Not only big corporations but a whole new generation of start-ups are indeed fulfilling authoritarian practises through commercialising AI-technologies, automating biases based on skin colour and ethnicity, sexual orientation and identity. They are developing censored search engines and platforms for authoritarian governments and dictators, refining high-tech military weapons, and guaranteeing order and control.

The participants on stage made clear that, looking at surveillance technology and face recognition software, we see how existing ethical and legal criteria appear to be ineffective, and a lack of standards around their use and sharing just benefit their intrusive and discriminatory nature. Current ethical debates about the consequences of automation focus on the rights of individuals and marginalised groups. Algorithmic processes, however, generate a collective impact as well that can only be partially addressed at the level of individual rights— they are the result of a collective cultural legacy.

Nowadays, we see technologies of control executing their tasks in aggressive and violent ways. They monitor, track and process data with analytics against those who transgress or attempt to escape control, according to a certain idea of control that was thought them. This suggests, for example, that when start-ups and corporations establish goals and values within software regulating public services, they do not apply the principles developed over century-long battles for civil rights, but rely on technocratic motivations for total efficiency, control and productivity. The normalisation of such a corporatisation of the governance allows Cisco, IBM and many other major vendors of analytics and smart technologies to shape very delicate public sectors, such as police, defence, fire protection, or medical services, that should be provided customarily by a governmental entity, including all (infra)structures usually required to deliver such services. In this way their corporate tactics and goals become a structural part of public functions.

In the closing panel “Citizens for Digital Sovereignty: Shaping Inclusive & Resilient” moderated by Lieke Ploeger, community director of the Disruption Network Lab, political scientist Elizabeth Calderón Lüning reflected on the central role that municipal governments have to actively protect and foster societies of digital self-determination. In Berlin, networks of collectives, individuals and organisations work to find bottom-up solutions and achieve urban policies in order to protect residents, tenants and community spaces from waives of speculation and aggressive economic interests. Political and cultural engagement make the German capital a centre of flourishing debate, where new solutions and alternative innovative perspectives find fertile ground, from urban gardening to inclusion and solidarity. But when it comes to technological transformation and digital policy the responsibility cannot be left just at the individual level, and it looks like the city government is not leading the way in its passive reactions towards external trends and developments.

Calderón Lüning is currently researching in what spaces and under what premises civic participation and digital policy have been configured in Berlin, and how the municipal government is defining its role. In her work she found policy incoherence among several administrations, alongside a need for channels enabling citizens to participate and articulate as a collective. The lack of resources in the last decade for hiring and training public employees and for coordinating departmental policies is slowing down the process of digitalisation and centralisation of the different administrations.

The municipality’s smart city strategy, launched in 2015, has recently been updated and refinanced with 17 million euros. In 2019 the city Senate released the Berlin Digital Strategy for the coming years. To avoid the harmful consequences of a vertical approach by the administration towards its residents, activists, academics, hackers, people from civil society and many highly qualified scientists in the digital field came together to rethink and redesign an ecological, participatory and democratic city for the 21st century. The Berlin Digital City Alliance has been working since then to arrive at people and rights-centred digital policies and is structuring institutional round tables on these aspects, coordinated by civic actors.

Digital sovereignty is the power of a society to control technological progress, self-determining its way through digital transformation. It is also the geopolitical ownership and control of critical IT infrastructures, software and websites. When it comes to tech in public services, particularly essential public services, who owns the infrastructure and what is inside the black box are questions that administrations and policy makers should be able to answer, considering that every app or service used contains at least some type of artificial intelligence or smart learning automation based on a code, which has the potential to significantly affect citizens’ lives and to set standards that are relevant to their rights. Without open scrutiny, start-ups and corporations owning infrastructures and code have exceeded influence over delicate aspects regulating our society.

Rafael Heiber, geologist, researcher and co-founder of the Common Action Forum, focused on the urgent need to understand ways of living and moving in the new space of hybridisation that cities of the future will create. Taking a critical look at the role of technologies, he described how habitability and mobility will be fundamental in addressing the challenges posed by an urban planning that lies in a tech-substratum. As he explained, bodies are relevant inside smart environments because of their interactions, which are captured by sensors. Neoliberal capitalism has turned us into relentless energy consumers in our everyday lives, not because we move too much, but because we use technology to move and tech needs our movements.

Heiber considered the way automobiles have been influencing a whole economic and financial system for longer than a century. In his view they symbolise the way technology changes the world around itself and not just for the better. Cars have transformed mobility, urban environment, social interactions and the way we define spaces. After one hundred years, with pollution levels increasing, cities are still limited, enslaved, and dominated by cars. The geologist suggested that the implementation of smart cities and new technologies might end up in this same way.

Alexandre Monnin, head of Strategy and Design for the Anthropocene, closed the panel discussion questioning the feasibility of smart cities, focusing on the urge to avoid implementing unsustainable technologies, which proved to be a waste of resources. Monnin acknowledged that futuristic ideas of smart cities and solutionism will not tackle climate change and other urgent problems. Our society is profit-oriented and the more efficient it is, the more the system produces and the more people consume. Moreover, tech doesn´t always mean simplification. Taking as example the idea of dematerialisation, which is actually just a displacement of materiality, we see today for example how video rental shops have disappeared almost worldwide, replaced in part by the online platform Netflix, which represents 15 percent of internet traffic.

Monnin warned about the environmental impact of tech, not just the enormous amount of energy consumed and Co2 produced on a daily basis, but also the amount of e-waste growing due to planned obsolescence and consumerism. Plastics are now a growing environmental pollutant and constitute a geological indicator of the Anthropocene, a distinctive stratal component that next generations will see. Monnin defines as ‘negative commons’ the obsolete tech-infrastructures and facilities that will exist forever, like nuclear power plants, which he defines as “zombie technology”.

The French researcher concluded his contribution pointing out that humanity is facing unprecedented risks due to global warming, and—as far as it is possible to know—in the future we might even not live in cities. Monnin emphasized that people shall come together to prevent zombie-tech obsolescence from happening, like in Toronto, and he wishes that we could see more examples of civil opposition and resistance to tech which is unfit for our times. Smart cities are not revolutionising anything, they constitute business as usual and belong to the past, he argued, and concluded by appealing for more consideration of the risks related to institutionalisation of what he calls “corporate cosmology” which turns cities into profit-oriented firms with corporate goals and competitors, relying on the same infrastructures as corporations do.

In its previous conference “Evicted by Greed,” the Disruption Network Lab focused on the financialisation of housing. Questions arose about how urban areas are designed and governed now and how they will look in the future if the process of speculation on peoples’ lives and privatisation of available common spaces is not reversed. Billions of people live in cities which are the products of privilege, private corporate interests and financial greed. This 20th conference focused on what happens if these same cities turn into highly digitised environments, molded by governments and billionaire elites, tech-engineers and programmers, who wish to have them functioning as platforms for surveillance and corporate intelligence, in which data is constantly used, stored and collected for purposes of profiling and control.

According to the UN, the future of the world’s population is urban. Today more than half the world’s people is living in urban areas (55 percent). By mid-century 68 percent of the world’s population will be living in cities, as opposed to the 30 percent in 1950. By 2050, the global urban population is projected to grow by 2.5 billion urban dwellers, with nearly 90 percent of the increase in Asia and Africa, as well as the appearance of dozens of megacities with a population of at least 10 million inhabitants on the international scene.

This conference presented the issue of algorithmic sovereignty and illustrated how powerful tech-firms work with governments—which are also authoritarian regimes and dictators— to build urban conglomerates based on technological control, optimisation and order. These corporations strive to appear as progressive think tanks offering sustainable green solutions but are in fact legitimising and empowering authoritarian surveillance, stealing data and causing a blurry mix of commercial and public interests.

Algorithms can be employed to label people based on political beliefs, sexual identity or ethnicity. As a result, authoritarian governments and elites are already exploiting this tech to repress political opponents, specific genders and ethnicities. In such a scenario no mass-surveillance or facial recognition tech is safe and attempts at building “good tech for common goods” might just continue to fail.

To defeat such an unprecedented concentration of power, we need to pressure governments at all levels to put horizontal dialogue, participation, transparency and a human-rights based approach at the centre of technological transformation. To this end, cities should open round tables for citizens and tech-developers, forums and public committees on algorithmic sovereignty in order to find strategies and local solutions. These will become matters of, quite literally, life and death.

Smart cities have already been built and more are at the planning and development stages, in countries such as China, Singapore, India, Saudi Arabia, Kazakhstan, Jordan, and Egypt. As Bazzichelli pointed out, the onset of the dramatic COVID-19 crisis has pushed social control one step further. We are witnessing increasing forms of monitoring via tracking devices, drone technologies and security infrastructures. Moreover, governments, banks and corporations think that this pandemic can be used to accelerate the introduction of technologies in cities, like 5G and Internet of Things.

There is nothing wrong with the old idea that we can use technology to build liveable, sustainable, and efficient cities. But it is hard to imagine this happening with technology provided by companies that exhibit an overall lack of concern for human rights violations.

Alongside the main conference sessions, several workshops enriched the programme. Videos of the conference are also available on YouTube.

For details on speakers and topics, please visit the event page here: https://www.disruptionlab.org/data-cities

The 21th conference of the Disruption Network Lab curated by Tatiana Bazzichelli

“BORDER OF FEARS” will take place on November 27-29, live from Studio 1, Kunstquartier Bethanien, Mariannenplatz 2, 10997 Berlin.

More info here

To follow the Disruption Network Lab sign up for its Newsletter to receive information about its conferences, projects and ongoing research.

The Disruption Network Lab is also on Twitter and Facebook.