Classic video games such as Pong, Tetris, Space Invaders, Pac Man and Super Mario have in the past decade inspired many artists in their work. The common link between all of these games is that they are very easy to learn and play. There is no need for manuals, just a few simple instructions on the screen. The graphics are simple, the colours few, the characters and style are pixelated. These games have influenced a whole generation and have over time become a part of our cultural heritage. Even today, these games still amuse and fascinate players and have also inspired various artists to use them in their art. In a series of articles, we will look at some classic games and give examples of how they have been used in art and what impact they have made on the art scene. First out is PONG.

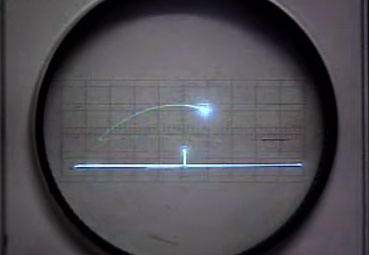

It was the American physicist William Higinbotham who in 1958 created what many consider to be the first computer game. The game was called “Tennis for Two” and was played on an oscilloscope with help of a simple analogue control.

Click here to view video on Youtube…

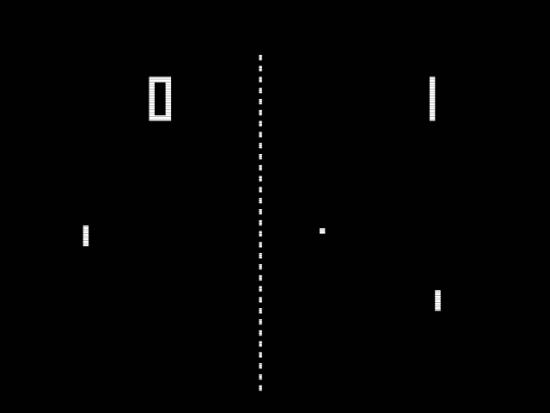

It took, however, until 1972, when the Atari Company, founded by Allan Alcorn and Nolan Bushnell, picked up the idea and created a commercial version and called it PONG, before the game became one of the first real big sellers for the computer games industry. PONG is a simple, minimalistic game that consists of two rectangles and a square, which symbolize two tennis racquets and a ball. You can either play against another opponent or against the computer. In this simplified version of tennis, the goal is to hit the ball so the opponent misses it.

PONG is probably the videogame that has inspired most artists over the past decade. When the Computer Games Museum in Berlin in 2007 organized a major exhibition entitled “pong.mythos” over 30 artists attended with works of art inspired by PONG. The catalogue explains why PONG fascinated so many artists: “No other video game has been the origin of artistic production quite as often as the simple black-and-white tennis game. In addition to its popularity, it seems to be this minimalism that especially appeals to artists, since the playing pattern is a virtual prototype of the essence of each and every communication situation: the ball as the smallest possible unit of information, oscillating between sender and receiver” (from the catalogue “pong.mythos” 2006).

The artist group /////////fur//// showed their “Pain Station” (2001) in which the player who missed the ball were punished with physical pain, a blow on the hand, heat or an electric shock. “Pain Station” connects the physical world with the virtual and the virtual player’s mistakes turn actual real pain.

The artist group Blinkenlights working in the urban environment was represented with a project that transformed a large office building at Berlin Alexanderplatz to a digital screen where passersby could play PONG on the facade with the help of their mobile phones. In the artists S. Hanig and G. Savicic’s work “BioPong” (2005) the ball was replaced with a living cockroach where the players would try to push the insect over to the other side. And in the group Time’s Up version “Sonic Body Pong” (2006) the ball in the game was only a sound which the players could hear in their headphones and with help of large green rectangles on their heads they would try to hit the sound from the ball.

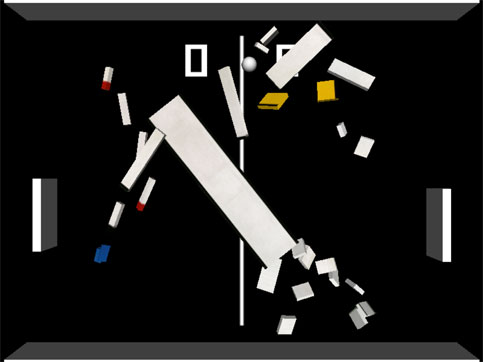

There are also many other examples that were not included in the exhibition “pong.mythos”. As early as 1999, the artist Natalie Bookchin made “The Intruder”, a work where PONG was one of 10 different videogames that she used to create an interactive artwork by Jorge Louis Borges short story “The Intruder”. The Danish artist Anders Visti mixed the game PONG with the art of Piet Mondrian in “PONGdrian v1.0” from 2007. The playing field in Vistis artwork reminiscent a painting by Mondrian but when the ball hits the fields it disturbs the lines and colour fields, and creating new opportunities and challenges for the player. Finally, I can mention the Swiss artist Guillaume Reymond, who has made a series of performances called “Game Over”. In a theatre auditorium, he creates animated sequences by using real people in colourful T-shirts, where each individual represents a square on a screen. By moving the people in the auditorium, he can create short video sequences, for example of PONG playing in the lounge.

The reason that PONG is so popular among artists is that it is one of the very first video games, and therefore there is a large identification factor and a strong relationships between the game, the player and the artwork. PONG is also one of the easiest games in terms of both appearance and to learn to play, which paradoxically makes it so easy to transform and use in different contexts. The phrase “less is more” seems in this case a good explanation why PONG has inspired so many artists in recent years.

Pong Mythos – http://pong-mythos.net/index.php?lg=en

Natahalie Bookchin – The Intruder http://bookchin.net/intruder/

Guillaume Reymond – Game Over http://www.notsonoisy.com/gameover/

Anders Visti – PONGdrian v1.0 http://www.andersvisti.com/arkiv_grafik/pongdrian.html

Image: SMartCAMP logo, all images courtesy of SMartCAMP

Part of New York’s Art Week, SMartCAMP, or social media art camp, took place on March 5th and 6th, at the Roger Smith Hotel in New York, a slightly unusual kind of place in that it’s a hotel with its own production company. That company’s artistic director, Matt Semler, who is also the director of The LAB Gallery, became interested in the ways Roger Smith marketers Adam Wallace and Brian Simpson were using platforms like Facebook and Twitter to build an online community. According to Semler, his curiosity “ultimately led to more questions than answers and we found ourselves wanting to bring the leaders in the social media (SM) art world together to talk about their process, goals and best practices. Once we came up with the name SMartCAMP we were pretty much off and running.” Conference organizer Julia Kaganskiy of New York’s Arts, Culture, and Technology Meet Up curated SMartCAMP’s program and a former actor, Danika Druttman, handled communications for the event.

In other words, from the beginning SMartCAMP was about people, people who post, blog, tag, add, and tweet, but above all, people who meet and link up through quirky, often unpredictable, circumstances to pursue a shared idea. According to the speakers in SMartCAMP’s program, this is the kind of easy serendipity that gives social networks their authenticity and value. While these qualities can’t quite be summoned, they can be encouraged and directed. For artists and administrators, the question is how to sustain these connections to build audience and patron loyalty. Whether you like the idea of artists taking on their own distribution, or whether you find it somehow uncomfortable, social media is influential and growing. As more than one person pointed out, social networking has surpassed pornography as the number one activity on the web.

Mark Schiller’s keynote opened the Saturday session. Well-known in the New York arts community, Schiller is the founder of The Wooster Collective, a public arts site that documents street art from around the world. Like many successful online projects, Wooster Collective began accidentally. Out walking his dog in his downtown neighborhood, Schiller began photographing street art, which he then posted online, forwarding the link to friends, and asking for their reactions. Soon his web page was managing hundreds of photos, receiving thousands of hits per day, and turning artists into online celebrities. Two Wooster Collective discoveries that have gone viral are Josh Harris, famous for his subway grate inflatable dog, and Jan Vorman, an artist who uses Lego bricks to patch crumbling city walls. Today, after eight years of posts, The Wooster Collective is the online authority on street art. Schiller receives a self-sustaining five hundred emails a day from artists who have done work, or have seen work, and would like to contribute. Wooster Collective also has a YouTube channel and a Twitter feed.

In many ways Wooster’s success seems unpredictable and non-reproducible, a fad, some kind of dumb luck. Yet, in retrospect, Schiller is able to point out specific qualities that made the site popular. First, there was page rank. Since no one was writing about street art in any other media, Wooster Collective’s art tags quickly went to the top of the search engine indexes. This kind of self-reinforcing rank allowed Schiller’s blog to get more traffic and, consequently, to pull more traffic from user searches. Second, ninety percent of the content on The Wooster Collective was original, making Schiller’s blog a feeder for other arts pages, increasing its incoming links and, again, boosting its reputation and its rank. Third, there are no ads at all on the Wooster site per se, mostly, Schiller says, because ads would be distracting both for him and his followers. Free from ads, Wooster Collective has no traffic stats to maintain, meaning Schiller is free to indulge himself in what his readers like best, Wooster’s own weird personality. On most days the site wavers slightly between media outlet and community bulletin board.

However, as important as his community may be, Schiller explained that Wooster readers are actually heavily restricted. The community is largely passive. Readers can email, but they can’t comment, upload, or see who else is online. Although some of site is user generated content, sites built on user content are notoriously second-hand and boring, so reader contributions are very heavily curated. The result is a blog that remains personal and interesting to all. Schiller also says audience building on the Wooster site has always been secondary to his main mission of sharing a passion for street art. According to Schiller, that passion is what works online and the effort to express it means a willingness to try anything. After all, Schiller reasons, “if you don’t like it, you can always stop. If a projects takes more than ten minutes to finish, stop. If it’s not fun, stop. If it’s not inspiring, stop.” Finding podcasts “not fun”, The Wooster Collective recently quit making them. They quit making mobile apps too. Schiller suspects that it is the resulting cheerfulness, lack of strain, exuberance, or even silliness, that connects an audience to a blog, a pursuit, or to an artist.

For Etsy, an online site where artists sell their work directly, community came first, web presence second. Anda Corrie, manager of Etsy’s Twitter feed, explains that Etsy was started at a time when the DIY arts culture was strong and growing, but artists still had few outlets for what they made. Etsy was one of the first sites to give them that outlet and, for a small commission, the site benefited greatly from its fortunate timing. Still, there is a balance between artist and audience that sustains Etsy and makes it work. In addition to responding to community needs, Corrie notes that the governance of sites like Etsy should be as transparent as possible. She reminds media managers rushing to reach out to remember to build a way for their readers and followers to reach in. Etsy uses a community council model. Councils change monthly, giving suggestions for improvements to the site and its forums. This is a time consuming model to attempt but, like Schiller, Corrie feels media planners who go through the motions without really getting involved are unlikely to succeed.

Michelle Shildkret, who represented Cake Group would say that you can’t fake what you are online, just as you can’t hire someone to “make you go viral”. She advises artists to slow down, figure out who to reach out to, where they are online, what they do when they’re online, and how someone might get their attention. When you can answer those questions, you’re ready to approach a social media plan. Shildkret also believes that a small, engaged community may be better than thousands and thousands of disinterested friends. Choose to introduce yourself and your work to places you like, make a difference there first, then advance slowly. John Birdsong of Panman Productions says artists often need to open up in exchange for popular attention. Birdsong endorses the strategy of a behind the scenes look at a studio or art process by posting “making of” videos to UStream or YouTube. These sentiments were echoed by others. Natasha Wescoat, a writer for EBSQ, the self-represented artist’s blog, became obsessed with eBay auctions as a community college student. Wescoat noticed that what honestly attracted her to an artist’s online profile was not necessarily the work. As an audience member, she also wanted personality, a connection, and some sense that there was a real person behind the presentation. Where Schiller describes a community that grows out of a shared passion, Wescoat sees community as a group centered on personality. Like Schiller, she encourages artists to try all ideas, continue with what feels right, and allow a web identity to evolve over time. For example, Wescoat describes her own online identity as an arc with three phases: experimentation, where she tried different approaches to making and selling work; narcissism, where she spent a good deal of time showing how the work was made; and establishment, where the size of her online audience is large enough to attract commissions from corporations and collectors.

Sharpie sketch queen and self-described “art school drop out” Molly Crabapple credits her web personality as fundamental to a full-time practice that draws commissions from the New York Times and Marvel Comics. Founder of Dr. Sketchy’s Anti-Art School, Crabapple introduced her online persona by compulsively posting to LiveJournal. Today, her favorite platform is Twitter and her media tool of choice is the one hundred and forty character tweet. Crabapple likes Twitter’s immediacy and tweets to get illustration suggestions from her followers, to find emergency crash spaces, and to “manifest” anything. She advises underrepresented artists to do whatever it takes to build a following online: friend friends of friends, promise to perform humiliating stunts for your followers, tweet about everything you do, reward your one hundredth or one thousandth follower with some kind of gift, a sketch or drawing, for instance. When the earthquake struck Haiti, Crabapple tweeted for drawing suggestions, drew those suggestions live online, then auctioned those drawings off in a benefit for Doctors without Borders. Yancey Strickler who co-founded the microfunding platform Kickstarter goes a step further. Kickstarter allows artists to post projects online and request small funding pledges from their followers. These pledges remain virtual until the project pledges reach full funding. At that point, sponsors pay up, the project is funded, and Kickstarter receives five percent of the amount raised. But pledge money is not always a reflection of your project pitch, Strickler points out, saying that what succeeds online is a good narrative and a connection with the audience that feels authentic. According to Strickler, people on Kickstarter are only somewhat concerned with the quality or originality of the work in front of them. More often, their decision to contribute to an artist’s goal proceeds along the lines of questions like “Do I like this person?” or “Could I be friends with this person?”.

If all this sounds a bit disingenuous or self-serving, remember that social media connects artists and audiences directly and that this connection now has its own considerations. There are some dangers in its manipulation, but the benefits need to be recognized. Adam Smith of Dance Theater Workshop’s and the New York branch of the Neo-Futurists uses blogging and community choreography as forms of outreach. While there are no hard numbers for increases in audience through the blog, DTW’s paid audience has gone from sixty to eighty percent of the house. Working on getting the tools right isn’t necessarily a negative and will probably take some work. Dancer Lisa Niedermeyer says: “You can’t just be clever, you have to be smart, and that none of this has been around long enough for any of us to be wise (yet). That any one experiment can be clever, and with speed and easy access can go live, but it takes being smart for it to be sustainable.”

Niedermeyer works on Virtual Pillow, the tech initiative of Jacob’s Pillow Dance. In some ways Niedermeyer considers the company’s online presence a fourth stage: “A global, interactive space serving a virtual community that might not ever be able to physically visit us in the Berkshires of Massachusetts, but highly value our archives, performances, professional school, creative development residency programs, etc.”

A second part of Virtual Pillow’s mission is to bring the work of the company, including its history, to a wider audience via social media, streaming sites, or any other online platform. Niedermeyer attended SMartCAMP for the chance to hear other institutions and artists discuss what worked and what did not. She says the conference gave her more perspective on the strategies available to Virtual Pillow: “I felt that the conference speakers and participants were really talking about the big picture, big ideas. Gravity Rail, for example, with their passion to explode open and transform eCommerce models for artists.”

Performers are not alone in the need to link up. According to Nancy Proctor, the museum is a distributed network whether curators accept that idea or not, and agile use of social media is essential to responsive curation. Proctor heads New Media at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, a museum which now gets more visitors online than in person. Are those online visitors any less real? Should their visit be any less satisfying? Should their use of the museum be any less respected? Noting that desktop activities are increasingly moving to the mobile web, Proctor urges curators to meet visitors where they are through sms, tweets, and mobile applications.

Examples of another kind of user centered curation came from Titus Bicknell, founder of pinkink, who believes audiences and their questions now lie at the center of any program strategy. Bicknell’s examples of user centered curation included a podcast that asks visitors to enter a space, look at the art, and record any questions they might have. In this curation model, socially aware programmers ask audiences what they would like to know, rather than telling audiences what it is believed they should know. Allegra Burnette, Creative Director of Digital Media at MoMA, pointed out excellence in web presence like the Indianapolis Museum of Art’s fine arts blog ArtBabble, but added that MoMA uses Twitter feeds specifically to talk about current exhibitions at home and elsewhere. MOMA also offers podcasts on iTunesU where, Burnette says, downloads have increased about ten times this year. More and more, curation extends beyond the exhibit to the conversation about that exhibition, a conversation that defines your institution on the social web through bookmarking, favoriting, collecting, sharing, recommending, and searching. Like the Wooster Collective’s Schiller, Burnett advises media managers to avoid blatant marketing and to discuss events of interest to readers whether those events are part of a home exhibition or are occurring elsewhere.

Even in competition with Arts Week, SMartCAMP sold out. In addition to a long list of good speakers, there was a great deal of conversation and connection going on across the seats, in the halls, throughout the lobby and meeting rooms, and at the bar. Absolutely no one was asked to turn off a cell phone. Executive producer Matt Semler says: “We trended on Twitter both days and ended up with 120,000 individual views on UStream. The audience was very nicely mixed. While we don’t have any specific data on demographics my impression was that the room was evenly split between art executives and artists.”

In April, Semler and Roger Smith Arts will present a cello performance by Peter Gregson from within a Morgan O’Hara installation inside The LAB gallery space in New York. As Gregson plays, O’Hara will perform one of her “Live Transmissions” of Peter’s performance. The event will be streamed live over UStream and, as with all LAB performances, will be viewable from the street as well.