1 May – 4 August 2019

Featured image: Portrait of Kathy Acker, San Francisco, 1991. Photo: Kathy Brew

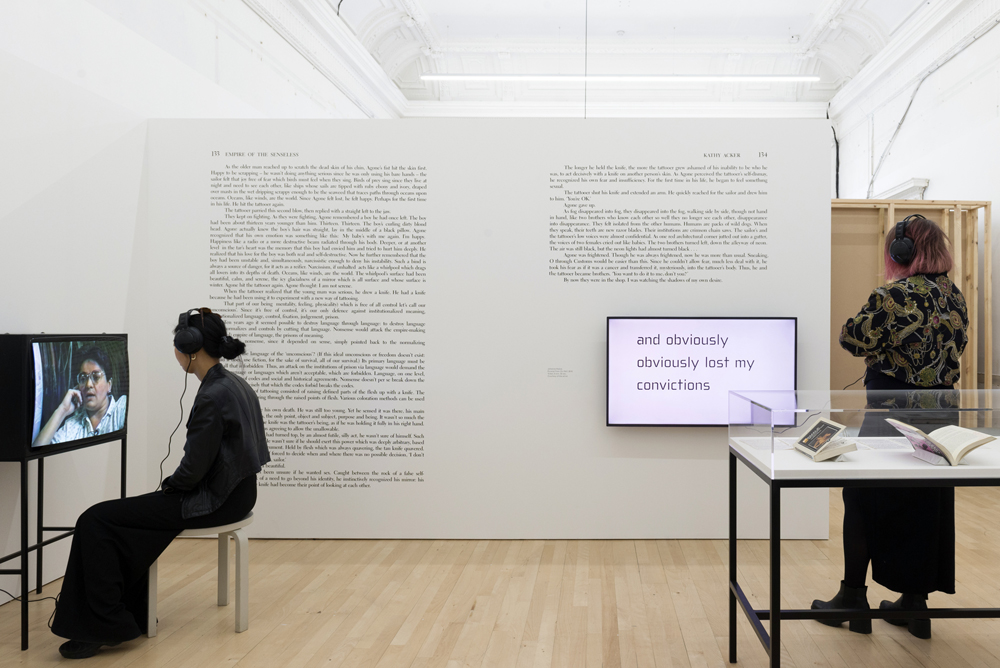

The latest exhibition at the London’s Institute of Contemporary Arts remembers the postmodernist writer Kathy Acker. The many Is in the exhibition title are suggestive of her focus on the exploration of identity and acknowledge the impact she made on the generations of artists following her. Apart from examples of Acker’s practice, such as the documentation of live readings and performances, music and text, this first exhibition dedicated to her in the UK, encompasses works by over 40 artists inspired by her legacy.

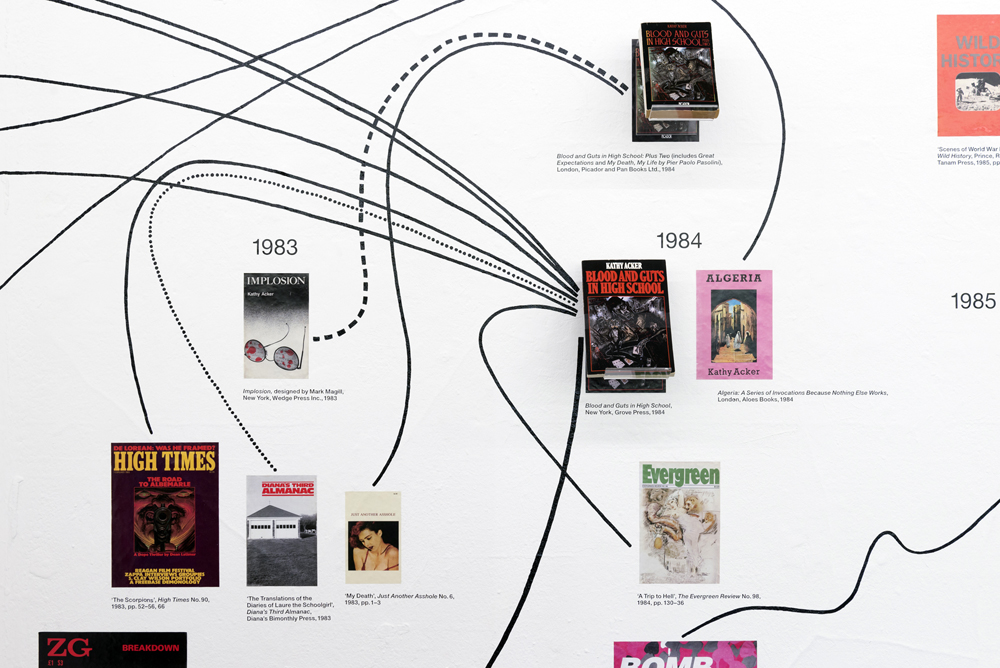

Acker’s relationship with the ICA has begun when she first moved to London, where she lived between 1983 and 1989. At that time, her anti-establishment and anti-patriarchal deconstructive philosophy fit perfectly in time with the atmosphere of the post-punk Tatcher England. She became a significant figure within the cultural landscape and a regular contributor to events at the ICA.

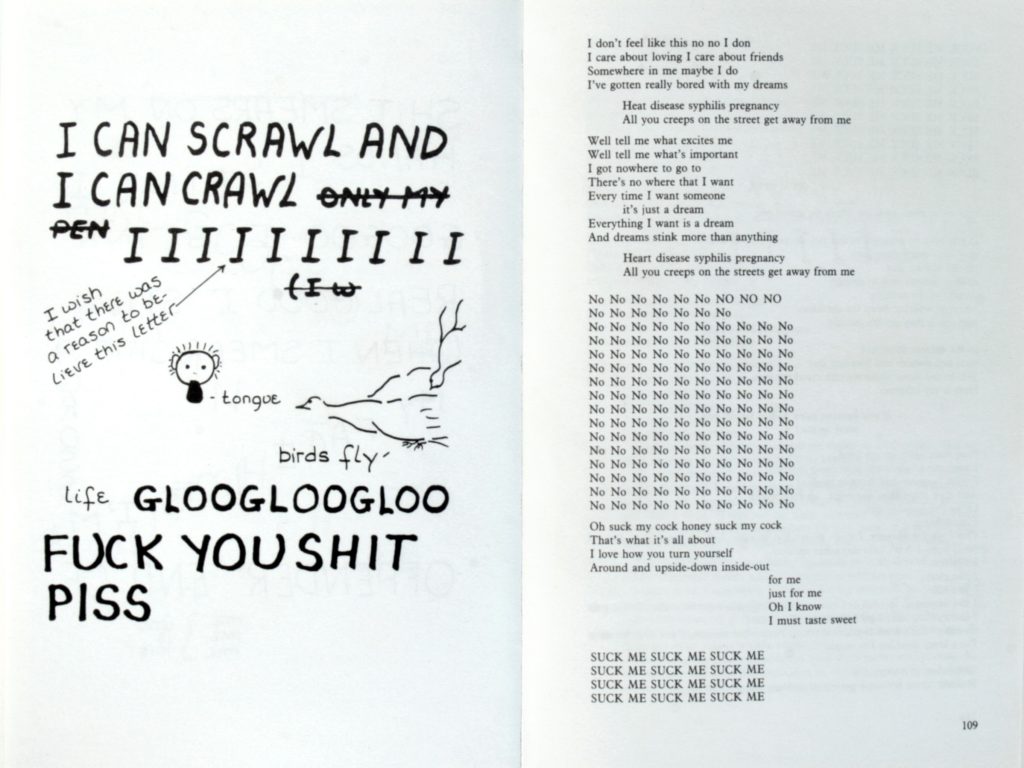

Kathy Acker was a writer who shook the punk art scene in the 70s and 80s New York. She was a lonesome figure in the East Village avant-garde, which at the time was dominated by men. In her prose, Acker often experimented with what being oneself meant. She herself said, “I was splitting the I into false and true I’s and I just wanted to see if this false I was more or less real than the true I, what are the reality levels between false and true and how it works”. Through her practice, she established a performative relationship to one’s identity, a means of exploration into the relationship between sexual desire and violence.

The language was her weapon. She treated it as a means of strong resistance towards patriarchal and heteronormative narratives in the public sphere. Throughout her writings displayed on the walls within the exhibition space, one can see her words from the book Empire of the Senseless (1994), where she declared: “Language, on one level, constitutes a set of codes and social and historical agreements. Nonsense doesn’t per se break down the codes; speaking precisely that which the codes forbid breaks the codes”. The two floors of the ICA are divided into eight sections, each corresponding to one of her books, with appropriate excerpt displayed. Her writing is at the core of the exhibition, on the walls, screens and in glass cases. There is a bit of inconsistency between the ways the literary works are displayed. On the one hand, the exhibition aims at bringing her legacy closer to the public, on the other some of them look hermeneutic when closed off behind a glass, like relics in an ethnographic museum.

However, the other works in the exhibition animate the space and the texts. The binding material between them is the preoccupation with the conflict between personal desires and the domineering narratives in society. Some of the first works to be seen are Jimi DeSana’s Masking Tape (1979) and Refrigerator (1975). The first one depicts a human figure wrapped in masking tape, only genitals exposed and the other shows a woman tied in the refrigerator. These black and white photographs contain suggestive and poetic qualities, also distinctive for Kathy Acker’s work. Further on, Acker’s pictographic “dream maps” which originally existed as large-scale drawings, are juxtaposed with works exploring the female desire in contemporary society, for instance, Reba Maybury’s The Goddess and the Worm (2015), a book telling a story of a dominatrix.

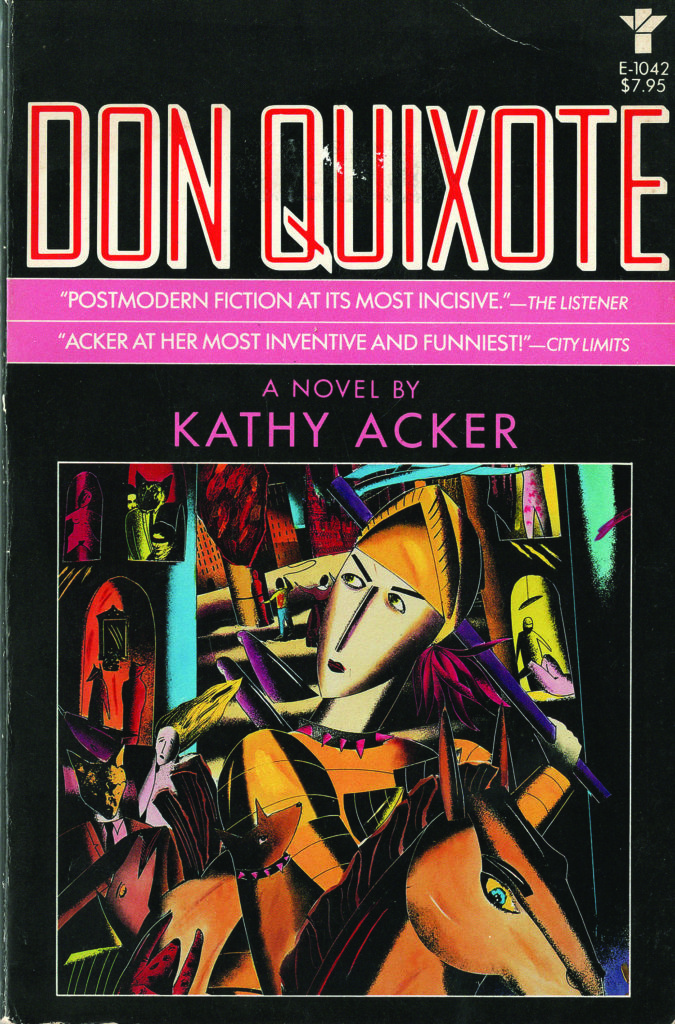

Acker critically assessed the societal norms, declared political relevance of one’s body and focused on marginalised groups. In one of her books presented in the gallery, Don Quixote (1994), the writer transformed the 17th-century canonical protagonist into a female, who becomes a knight by having an abortion and embarks on a journey to address the inequalities of Nixon’s America. Continuing to the second floor, one finds artists addressing the experiences of people who do not confine into the strict gender binary categories and the limitations of our language to describe them. At a back wall of a room, positioned opposite David Wojnarowicz’s works from the Arthur Rimbaud series, are three drawings by Jamie Crewe. Glaire takes Estradiol (2017), Potash takes Spironolactone (2016) and Saltpeter takes Verdigris (2012) show pairs of figures inscribed with the possible side effects of taking steroid hormones, compared with other substances.

The exhibition might leave the viewer in awe and with a head full of ideas. It is an ambitious project, as it addresses the integrative nature of Acker’s practice and evaluates her concepts. It is particularly successful at recognising the writer’s role in the experimental literature scene and the power of her legacy. At times when the society is becoming increasingly politically divisive and the inclusivity comes at a high price for some, it is crucial to remember the pioneers who promoted diversity in the arts. Conceptually speaking, the exhibition structure works well with the aesthetic premise of Acker’s work and creates a dialogue between all the participating artists. However, at times the experience might be overwhelming and becomes an exhibition-goer’s nightmare as it is heavily loaded with text.

I, I, I, I, I, I, I, Kathy Acker finishes with a wall drawing by Linda Stupart, A dead writer exists in words, and language is a type of virus (2019). In it, organic elements, serpents’ eyes and stones are tied to a blueish core resembling a cloud. Around it, there are red tentacles which enliven the virus, which spreads around the wall surface. It is mesmerising, twisted, creating a web of influences. Likewise, it corresponds with the exhibition structure, which is at times challenging to navigate, but ultimately transformative.

It was not the cyberpunk universe you were looking for.

Our nostalgia centres were lit up with a cut from a flying car to a full screen eyeball staring across the opening scene, synchronized on the script and musical score of its 20th century precursors’ timing. From there, audiences of the Blade Runner sequel were dropped into a pale California wasteland blanketed with conglomerate agricultural biofarms, an antithesis to cyberpunk’s damp, urban hybridity. The green, utopic space beyond the city– only glimpsed at the end of the 1982 original theatrical release and removed entirely in the director’s cut– was where we started from in Blade Runner 2049, and (surprise) there’s nothing but the dystopia of the anthropocene to look forward to there either.

Times change.

The recently post-industrial, 20th century cyberpunk rebellion of bodily sensuality: the noir lighting, the baroque candelabras burning, the lingering fingers stroking out haunting piano music; these were relics now, hinted at, ghosts of a genre in its past moment. Even the endless rain characteristic of the cyberpunk genre was repeatedly replaced with snow in Blade Runner 2049. A borrowed soundtrack teasing the familiar bridge to a heroic death scene came without poetic dialogue or even a witness. Rogue replicants were not criminals, but escaping criminality. Even memories were no longer stolen in this world, but legally manufactured, a convention stripping the typical cybernetic plot of bioharvesting found in cyberpunk down to a more contemporary, bioengineered ethics of classed and raced co-humanity if ever there was one. No, this ethical failure was smoother, blended into liberal values and legal structures, more sanctioned somehow.

The 80s cyberlibertarian world of the white lone wolf, struggling for autonomy in a hybrid, post-globalized world of orientalist economic takeover, had passed by in the great data “black out” of 2020 apparently, and Denis Villeneuve didn’t care about your need for consistent genre romance. Sort of. Rather, the director brought the audience’s need for Blade Runner nostalgia in and out of the sequel like a tool, cuing our attention to wait for it, partially rewarding us with a sensory, semi-nostalgic moment, only to glitch before nostalgic completion. Again and again, it was invitation and estrangement from our own expectations. Blade Runner 2049 was a highly self-aware remix of its own postmodern references and refusals in a predetermined world.

Perhaps a hybridity across two cyberpunks of historical time and cultural change was apropos. Ridley Scott’s genre critique of the corrupt corporation had evolved since its 20th century take in the Alien franchise, expanding to consciously address our own implication in the techno-dystopian social narrative. It turns out that we are no longer universally laboring blue collar victims in the secretive horrors of impending biopolitical technocracy. Rather, we are eager and satiated participants in its isolating ubiquity; high tech consumers implicated in all of the attendant social stratification, inequality, and suffering that its warm glow of access masks and accelerates, from facilitated gentrification and casualized labor, to the toxic, extra-legal wastelands of dead electronics processing.

Disruptive innovation has predominantly benefitted the 21th century, western, science fiction audience. Our classic cyberpunk desire for the vindication of the social outlier– the androgynous Sigourney Weaver in a corporate-threatened future of full equality and bodily autonomy, or the replicant who can reclaim a subjectivity beyond his or her social paradigms and slave programming– has since been turned on its anti-establishment head. Scott’s film Covenant saw this come to fruition when the Menippean Anti-hero, Bakhtin’s rebellious, paradigm-questioning literary figure cloaked in the absurd eloquence of language, is fledged into a full sociopath. We saw this in the philosophical and intellectual character of David and his calculated experiments to replace the evolutionarily inferior human species. If Menippean satire is “a genre for serious people who see serious trouble” (Howard Weinbrot), than what is this?

By Covenant, our anti-hero no longer presented the humanistic redemption narrative of the Menippean Nexus 6 leader, Roy Batty, in the original Blade Runner. Instead, Covenant gave its inverse: a regressed society being shown the mainstream values it has come to love and endorse in a world of neoliberal anti-establishment leadership. So much for the underground resistance crouching in the street garbage. The 21st century universe of cyberpunk has been one of well-mannered disruptive innovators of the species, philosophically visionary proponents of transformative wealth models built on slave bodies, and the “technê-Zen” veneered (R. John Williams) institutionalization and naturalization of technological sociopathy. Here is a social darwinist instrumentalism for our post-human age of market-driven measures of social success and impending climate change. In this universe, androids can be humanist while humans can be androids in an inhuman system, conveying either ‘progress’ by any means necessary or a losing sense of civilizational duty. Whose side, Covenant asked of us, before its devastatingly feel-bad ending, were you hoping would win anyway?

David, it turns out, was the only anti-hero we deserved now.

Denis Villeneuve’s sequel fits surprisingly in this updated cyberpunk universe. Like Walter in Covenant, the replicant hero who becomes Joe in Blade Runner 2049 (in contrast to Roy Batty) clearly lacks the eloquent language and especially satire of the subversive, Menippean Anti-hero character. Surprisingly, we find his strain of articulate stream-of-conscious in the tech empire guru played by Jared Leto, drained of all the feeling and trickster-like ability of Roy Batty. Joe, however (like Walter), is simple and humble in his speech, seemingly able to feel but dying suggestively in silence off screen. Robbed of the poetic dialogue expected of the death scene, only a soundtrack bite nostalgic of Roy Batty’s final scene signals a death of redemption for Joe in Blade Runner 2049. Yet the unsentimentally raw, blank slate of Joe’s expression asks of his audience: What do we see through his eyes? What language could possibly be used here to convey the gravity of a moment when power so regularly denies and manipulates the language of our experiences? In this silence, we are perhaps left to only wonder what we would be feeling.

What if it had ended differently? Would Roy Batty’s eloquent speech achieve the same humanizing disjuncture today, or does it really belong now to Niander Wallace, our tech monopoly visionary of the neoliberal age, emptied of any contradiction with the smooth flow of progress rhetoric and sociopathic public morality? Niander Wallace as foil who cannot stop talking makes Joe’s uncharacteristic silence all the more uncanny. According to Jonathan Auerbach, the uncanny involves a “trespassing or boundary crossing, where inside and outside grow confused… reveal(ing) dark secrets hidden within.” Auerbach is talking about film noir here– a highly unsettling sensory genre metabolized into the late Cold War aesthetics of the Blade Runner world. But perhaps we can relate this psychic role of the filmic uncanny to other hybridities explored through expressionist media, where the formal manipulations of sight and sound once conveyed the uneasy clashing of two worlds affectively.

Is Villeneuve’s silent denial of a hero’s dialogue in a death scene, for a Blade Runner audience, purposely estranging? Does it achieve the same, disorienting “uncanny bodies” (Robert Spadoni) that silent film audiences, unaccustomed to sound in their movies, reported with the introduction of Talkies? Film scholar Shane Denson describes how post-Talkie movies of the Thirties like Frankenstein (1931), were created in a period of transition and between the old and new ontologies of silent and sound film media. Denson argues that such films, working after the initial novelty of Talkie exposition wore off, played affectively with the new hybridity of films formalist storytelling qualities. In doing so, these films drew attention to our participation in media: “sight and sound conspire(d)…to encourage the viewer’s medium sensitivity, to coalesce with the perception of a constructed monster.” And what is a sequel, after all, if not a constructed monster of narrative to become conscious of?

“Questions.”

We live in a time of the seductive post-human technologization and normalization of very inhuman institutions, public policies, and person-like entities whose social impacts are all too often screened over with ‘alternative’ narratives of language. Glitches in this flow of mainstream mediated ways of knowing can be more than anti-nostalgic; they can be disruption to the alt-fact hyperreality in the neoliberal 21st century. Are uncanny bodies of the sensorily unexpected (or, even, dissected) what we have left to successfully slow down and stutter our neoliberal ubiquity for hearing chasm-filling speech? Can such estrangements allow us the conscious relationality to once again actually hear and see how we are hearing and seeing each other?

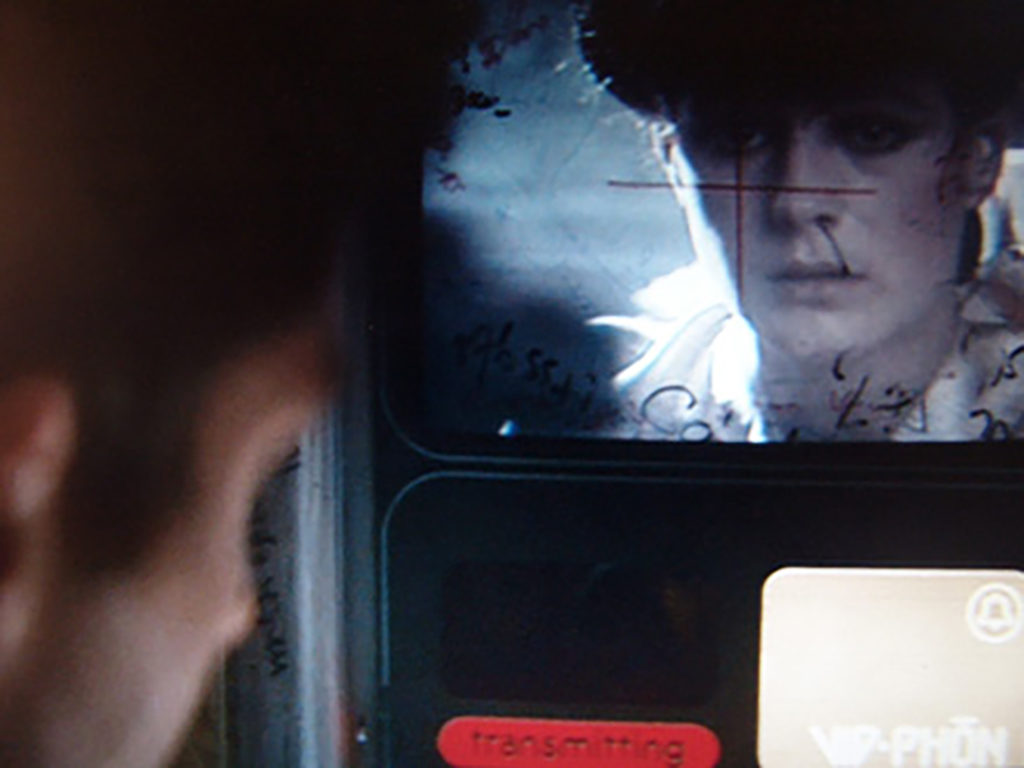

It is convenient to note here that the technological imaginary of the first Blade Runner movie refused ubiquitous surveillance. Blade Runner 2019 even refused a conception of the personal communication device so often credited with fracturing collective sociality in both sci-fi and reality. Decker, for example, calls Rachel from a public videophone in a bar. Whether human or replicant, technological worlding of the original Blade Runner insists on the communications scale of face-to-face human relationality. By the end of Blade Runner 2049 this same scale of technological imaginary in the original film returns. It is the death of one body, the replicant called “Luv”, that seems to end the limitless reach of panopticon technology that helps advance the plot.

Some kinds of love can destroy. Scene from Blade Runner 2049

This act leaves the future of Blade Runner’s Earth yet again to the relations between two, individual physical bodies. With the 1% most likely afloat in the outer world colonies, we might assume this means that it’s up to Us to cross the interface of hyberbaric differences. At a time when love has become perverted with neoliberal logic– instrumental, utilitarian, stripped of its greater sense of equality or duty– it seems that Villeneuve graciously gives us an answer here, if not a fantasy to hold on to. Perhaps one consistency in the Blade Runner franchise is the argument, like that of Junot Diaz on neocolonial oppression (as if it ever ended) and the uptick of white supremacist domestic terrorism, that it is ultimately intimacy with the Other and rejection of the glorified “lone wolf” mentality that must be revolutionary: “Vulnerability is the precondition to contact.” What if being in our present moment requires the vulnerability of silence?

“Listen:”

Nostalgia has come unstuck in time. In Ghosts of My Life, the late Mark Fisher wrote extensively of the threat of nostalgia in postmodern cultural production. Building on theorists Frederic Jameson and Bifo Berardi to explain the bending of new technologies to recycle comfortable and profitable cultural forms for capitalism, Fisher explains how “…the nostalgia mode subordinated technology to the task of refurbishing the old”, not of specific past styles, or periods, but forms of never-fully-present time asynchronicity. Consider it like another outdated, self-reproducing model, ever expanding all around you to stay relevant. Perhaps you can finally see its now, like a loose eye, engineered, removed from its familiar socket.

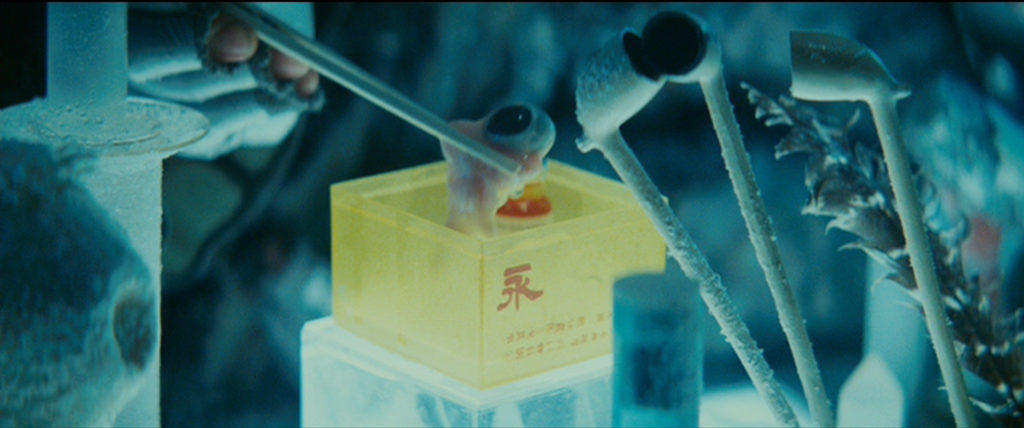

Transgressive fiction has this way of making our boundaries visible in the crossing. The reader may resist its dehumanization, suddenly queasy. Barthes once wrote about the surrealist Georges Bataille’s Story of the Eye, a modernist novel from the early mid-20th century which indeed involves a plucked eye and its “metaphorical journey” across other eye-like images. An object, he wrote, “can pass from hand to hand… or alternatively it can pass from image to image, in which case its story is that of a migration, the cycle of the avatars it passes through, far removed from its original being, down the path of a particular imagination that distorts but never drops it” (his emphasis). Barthes felt The Story of the Eye was less a novel and more like poetry. Through its avatars and crossing of sensory metaphors, the eye simultaneously “varies and endures.” Consider the following example of crossing sensory metaphors from the Blade Runner sequel: eyes, cells, tears, rain, leaking, bleeding, blinking, seizing, splashing, drowning, watching, “cells”. And what if this thing we now strangely see so differently is neither naturally born nor autonomous, but a constructed thing?

How eerie.

Eerie like the absence of “future shock” in the futuristic. According to Fisher, nostalgia mode production is an aspect of the “cultural logic of late capitalism” that “…disguise(s) the disappearance of the future” and prevents any real possibility of innovative “rupture”. Nostalgia in our entertainment helps stabilize the “cultural deficits” created under globalization, soothing the simultaneous “exhaustion and overstimulation” of instantaneous and transactional relations we can’t seem to deal with. It fills a high-speed chasm of emotion, truth, and meaning. It denies us the “uncanny” recognition of our temporal futurelessness, left teetering on neoliberalism’s precarity of resources “despite all its rhetoric of novelty and innovation…”

Let’s just be honest here: by the time the Coke commercial hologram showed up in Blade Runner 2049, it was a joke on our desire for even nostalgic product placements.

Nothing changes.

Dipping into the media art world at this borderland, theorist and filmmaker Hito Steyerl writes in “A Thing Like You and Me” about the video that David Bowie put out in 1977 for “Heroes”:

He sings about a new brand of hero, just in time for the neoliberal revolution. The hero is dead—long live the hero! Yet Bowie’s hero is no longer a subject, but an object: a thing, an image, a splendid fetish (…) the clip shows Bowie singing to himself from three simultaneous angles, with layering techniques tripling his image; not only has Bowie’s hero been cloned, he has above all become an image that can be reproduced, multiplied, and copied, a riff that travels effortlessly through commercials for almost anything, a fetish that packages Bowie’s glamorous and unfazed postgender look as product. Bowie’s hero is no longer a larger-than life human being… but a shiny package endowed with posthuman beauty: an image and nothing but an image.

What are we to do when no degree of protest or declaration can make an exploited object be seen as a subject? Where is one to find anti-heroism in all of this? Let us be objects of severe agency then. Models that are perhaps transferrable, but unobtainable. One of a kind and replaceable. Constructed yet autonomous.

Perhaps then we can only view these things in suspension: the need and refusal of nostalgia as liberating human process, the uncanny increments of our cultural evolution to product and media-focused estrangement, the will to see one’s own familiar pixels blown wide open. “Digital information is … characterised by transformation, degradation, circulation,” explains Hito Steyerl in an interview in Rhizome, “but also by its surprising ability to mutate and produce unpredictable results. The glitch, the bruise of the image or sound testifies to its being worked with and working; being passed on and circulated, being matter in action.” Futureless. As futureless as staring into a present ruin, expansive but without destination, the destination without purpose.

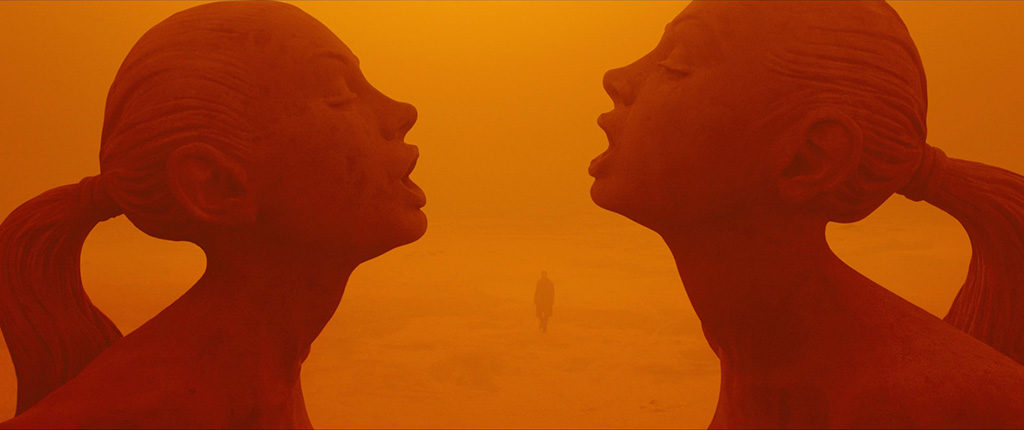

Apropos, then, how our old and new heroes meet in that ruined casino scene, outcasts of white difference (by the future racialization of the synthetic) in an atemporal Las Vegas, framed by primordial Seven Wonder monuments to the our foundational schisms of misogyny (yes I’m also talking about me).

In this incarnated ruin of our stubbornness for cultural mythologies, I was struck by the brilliance of the fight scene, the director literally exploding our pixel expectations of 20th century nostalgia as soon as Harrison Ford makes his long-awaited appearance. The sonic build-up of Decker’s familiar piano in the distance was dissolved by the strange sound of his disembodied voice un-cueing an upcoming appearance in the scene, his visual reveal in that moment of our auditory let down, confusing: Desire misfiring. The ensuing cyberpunk clash-as-fight-scene of 20th century romantic and 21st century post-romantic dystopic characters corresponds to the casino’s hologram interface of an imagined, mid 21st century entertainment technology; all of the expected glamour and nostalgia is allowed to barely seduce us before sputtering and malfunctioning as filmic metascene. Within the plot, these post-apocalyptic hollywood holograms are also a sign of the future sentience to come in the character of Joe’s AI wife, Joi, and a warning that all technology rebels and mutates from initial human intentions, no matter how superficial the design intentions.

My interpretation of this violent casino stage scene in light of a more recent American mass shooting of an ever-expanding, historically singular, and self-containing statistic of “largest ever” is not lost on me. Neither is the choice of mid 20th century entertainers like Elvis and Monroe who notoriously performed like automatons with post-human qualities, their movements in time-space of perfect bodies turning on the master clockwork of a still-industrializing cultural machine before blowing apart, fragmenting. Their avatars echo of consumer-creator bodies in our postindustrial world of 2.0, gig labor, automated economic transactions feigning meritocracy, and a model of precarity demanding the inhuman perfection of individual responsibility for every movement which can shudder, glitch, and explode on other people all too frequently.

This failure is that of speculated, plotted, rationalized, and technologized courses whose error cannot be properly imagined, only realized and refused in the ruins of a short-sighted economic-cultural imaginary. Our looking back on dystopia hints at our present expectations only.

“Irreversability.”

“It’s difficult for someone of my generation to break free of the intellectual automatism of the dialectical happy ending”, writes Bifo Berardi about irreversability. He compares this “taboo” concept to the “silent” apocalypses of our endless growth mentality, like Fukushima, corporate disaster unaccountability, socialized scarcity adjustments, and our silence on fellow human suffering. His book, The Uprising: On Poetry and Finance, speculates a “process of subjectivization” for the return of solidarity to a “social body”. This is the social body being culturally reprogrammed away under our collectively isolated movements of relentless market-driven consumption and precarity (individualist and systemic, like the fascist choreography of Kracauer’s Mass Ornament, or the Las Vegas showgirl spectacle). We might consider these grinding automaton gears of consumption and precarity the logics of late-terminal capitalism for clarity, it’s refusal a glitch in our clockwork performance. What is one to do for a postmodern exit other than to shudder, to write off the page? Ultimately, Berardi’s book leaves us more with a hope for our relational redemption from neoliberal culture through “sensibility” than it does with answers.

Blade Runner 2049 may not have been the sequel people wanted, but its confrontations with its own expectations provided a little of the things we need: a vision of the finite and anthropocene, a postmodern exit to the endless technologized avatars of getting what we think we want, our profound silence of the awful price. The film’s self-aware, nostalgic ruin leaves us with a little less of the typical sequel’s fourth wall, and an identification with its lonely bodies, caught in action between clockwork cultural predictability and its refusal. These bodies may or may not have the capacity for real love, but they are vulnerable at least to a larger sense of duty that Humanism, in all its universalizing failures, really needs. In this hybrid space of ontological awareness of the facets of knowing, experience and process, Blade Runner 2049’s success was inbetween all the things it could never definitively be. We too might realize that ‘doomed to fail’ may only be our insistence on choosing from a predetermined relational binary.

A distant song floats into the scene.

…“Though nothing, nothing will keep us together…”

When I saw Blade Runner 2049, in was at one of the remaining four hundred or so drive-in movie theaters left in the United States. I went back in memory to my kindling college interest in what I study and consider Avantpop, surveying the changes, considering its meaning and meaningless in my social development as a scholar: working class, woman, white, heterosexual; accepted and refused and abused entrances. The sequel came less than thirty years later in the revolution of a world for me, but I travelled farther to get there, out to a dark semi-rural drive-in beyond the city, and a memory of popping in a VHS tape almost 20 years ago simultaneously. I time-traveled mass media ontologies. I posted an instagram picture. It was semi-romantic nostalgia for me. But I still see that there is only now to change what we’re doing. And it is terrifying.

It’s quite an ending, to just die in silence, isn’t it?

But the fourth wall was always part of this, you know.

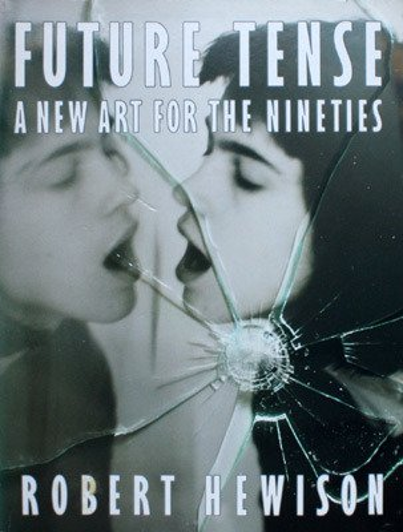

This article revisits Robert Hewison’s book, Future Tense: A New Art For The Nineties, [1] published in 1990. The book focused on contemporary attitudes to art, architecture and design that manifested in what had come to be called the postmodern era. Earlier avant-gardes of collectives and groups such as Dada, Situationism, Fluxus and the Lettrists had incorporated new technologies and challenged the material values embraced by museums and traditional hierarchies in modern art and capitalist society. Hewison set out to discover the ways in which artists of the 80s contributed to a “critical culture” for the 90s. [2]

In the 70s in the UK, art had a role to play in changing society, transforming relations to controlling production and critiquing the role of the establishment. Hewison’s mission was to observe contemporary culture happening in the late 80s in Britain with an emphasis on the future. Even though there had been a massive evolution in culture; within and across the fields of music, art and theory, it was also a new dawn for capitalism as it morphed into what we now know as neoliberalism. By revisiting Hewison’s book I hope to elucidate what the cultural shifts and differences in our art culture then and now are, and invite you the reader to reflect on what they mean to those of us engaging with and practicing across the fields of art, technology and social change today.

The way Hewison deals with postmodernism and its rapport with art and society is complex. He appears to regard much of the established art promoted in the late 80s, such as works by Jeff Koons, as banal marketing schemes, appealing to the interests of a privileged art-buying elite. He is more positive about grass roots communities re-appropriating and remixing art culture for others to claim on their terms. Michael Archer in his review of Present Tense in Marxism Today (1990) observed that not only was Hewison critical of modernism but also of postmodernism, which did little more than signal modernism’s ending. [3]

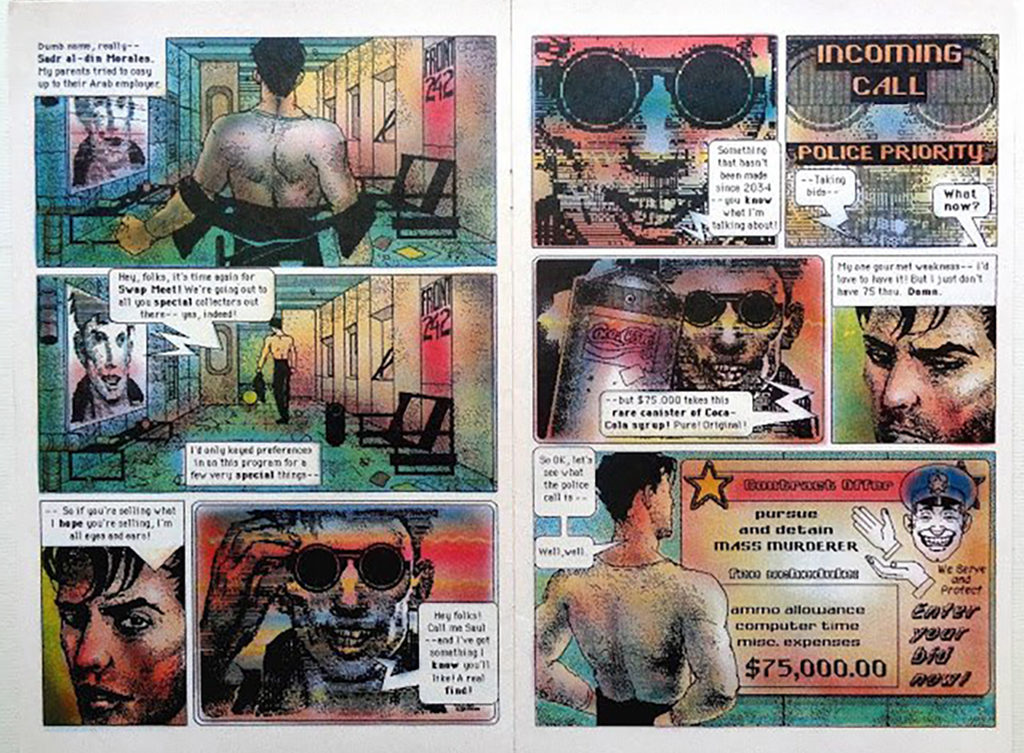

![[4] (Hewison 1990)](http://www.furtherfield.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/hewison1.jpg)

Lyotard argues that the grand narratives of 20th century modernism did not produce the benefits expected; rather, they have led to overt or covert systems of oppression. From this perspective the French Revolution and classic Marxism are seen only as forms of overarching and oppressive, ideology. Frederic Jameson offers another perspective on the ideas and social contexts around postmodernism. In his book Postmodernism: Or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism, Jameson says “It is safest to grasp the concept of postmodernism as an attempt to think the present historically in an age that has forgotten to think historically in the first place.” [5]

Future Tense’s cover image on the front of the book still feels contemporary. It shows a young woman about to kiss her mirror image while in front of a cracked glass, window. It alludes to a sense of culture – felt then as we still feel it now: as a disjointed picture of the world where modes of thinking and representation show us fragmentations, discontinuities and inter-textuality, and ‘bits-as-bits’ rather than unified objects. If the image were created now with a smashed up computer or mobile phone screen or an interface, its message would not be so different. We tend to beam our faces at our computer screens and then the screens beam right back at us, reflecting at us like data-mirrors, showing back not only a distorted image of ourselves but also a distorted multiverse.

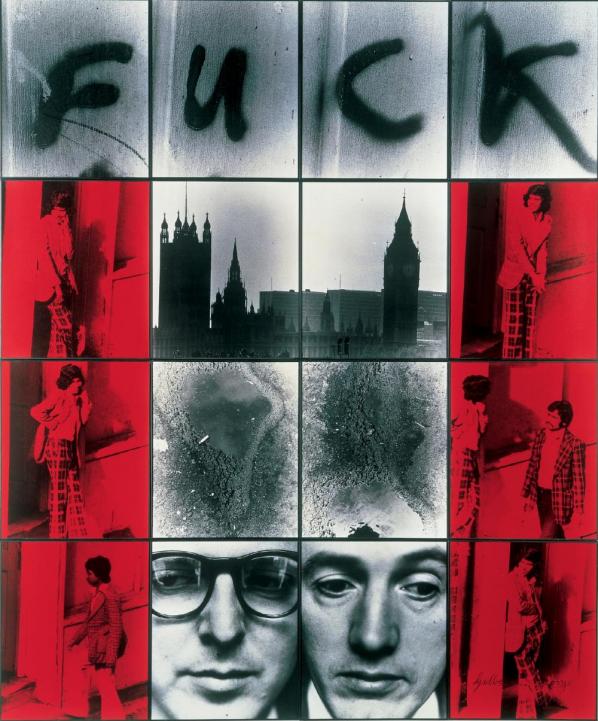

There has always been an irony at play with Gilbert & George. They usually expound a kind of punk aesthetic as an edgy chic; your lowest, basic, bigoted and unreconstructed inner ape giggles at their poo jokes. Yet while they subvert the idea of the ‘high’ of ‘high art’ by breaking life-style taboos they never bite the ‘high’ hand that feeds them. They know that shock is a dead cert currency just as the gutter press understands that sex and outrage sells, and that ethics and criticality get in the way of free market play. They sit well with the younger establishment in the arts, especially Damien Hirst and his peer YBAs, and similar Saatchi and Saatchi marketing investments.

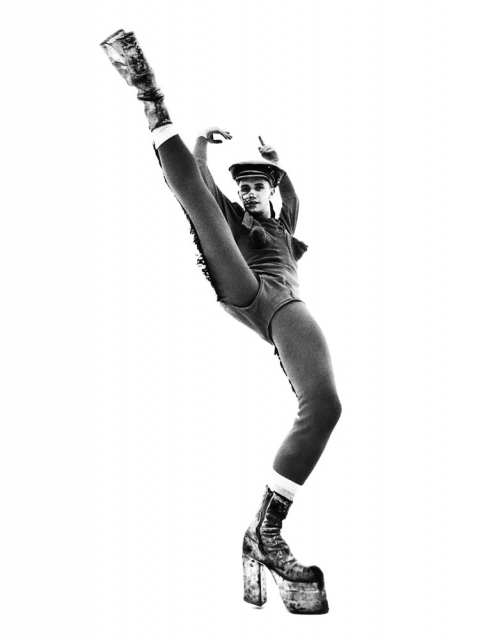

Hewison discusses Saatchi and Saatchi’s gallery space, and how the work presented in the space achieves an apparent purity, which detaches it from life, and that it has that autonomy within its own sphere which much twentieth-century art has sought to achieve. But in doing so it has separated itself from that other impulse, to use art as a means of revisualising, and so changing the world. [6] (Hewison 1990) This is still a big problem with art across the board even now. Most art agencies, orgs and galleries, are still separated from people’s everyday life experience. In contrast Michael Clark and his dance company was and still is a breath of fresh air. Even though he was classically trained, Clark tore “up the conventions of ballet, mixing sound and image in a rapid collage of creation, quotation and reference that plunders popular culture with calculated offence.” [7]

Cross cultural and interdisciplinary collaborations have been another marker of radical transformation in the postmodern era. Clark’s collaboration with the punk band The Fall in 1988 is a case in point where two different fields meet and create a brilliant outcome.

“I’ve always had a very strong relationship to music, to punk and pop – David Bowie, Iggy Pop, Sex Pistols, especially The Fall. The Fall’s song “New Puritan” was kind of a clarion call to me, not just because its rhythm is so ramshackle. When you listen to it, you wonder, “How the fuck do the musicians stay together?” Apart from that, the song encouraged me to say, “Wow, I’ll do it just like Mark E. Smith!” You know, “New Puritan” was against the idea of a big company, and I didn’t want to be employed by anyone. I didn’t want to sign a contract. I wanted to make my own work. I wanted independence, my own company. Mark E. Smith was definitely an example for that.” [8] (Clark 2014)

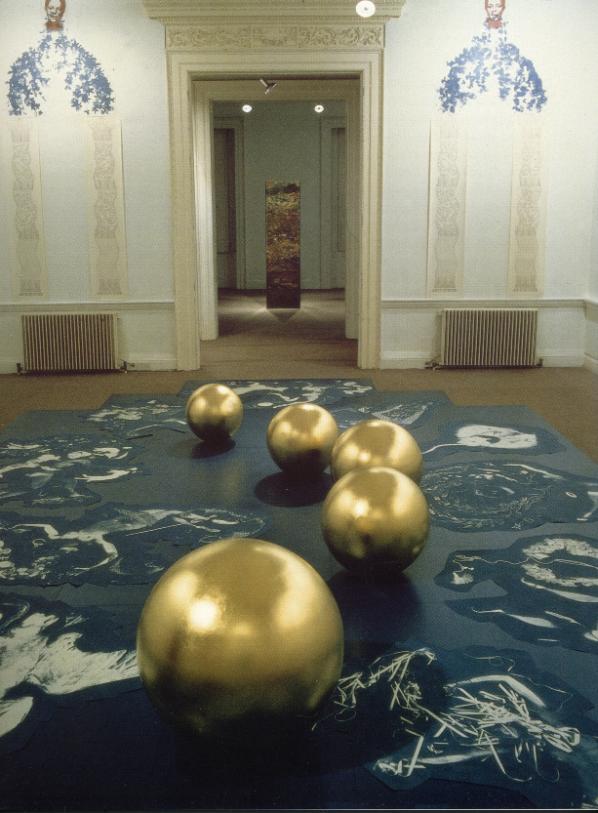

Many women artists during the 80s and 90s were using their bodies and identity as part of their art practice. Perhaps, one of the most treasured in the UK and greatly missed is Helen Chadwick who died on the 15th March 1996.

“Long before the current artistic obsession with the human body as a means for exploring identity, Chadwick had declared that “my apparatus is a body x [multiplied by] sensory systems with which to correlate experience”” [9] (Buck 1996)

Yet, her work resonates beyond her time period and still lives on through individuals inspired by her imaginative works to this day. Hewison dedicates five pages to Chadwick, and when discussing her installation Of Mutability, he says her work possessed a particular autonomy and, “Chadwick has found that the piece is most quickly appreciated by bisexuals who apprehend more easily the polymorphous nature desire.” [10] (Hewison 1990)

Hewison refers to the media baron Cardinal Borgia Gint in Derek Jarman’s film Jubilee, the baron in the film says “You wanna know my story, babe, it’s easy. This is the generation of who forgot how to lead their lives. They were so busy watching my endless movie. It’s power, Babe. Power. I don’t create it, I own it. I sucked and sucked and sucked. The Media became their only reality, and I owned the world of flickering shadows – BBC, TUC, ATV, ABC, ITV, CIA, CBA, NFT, MGM, C of E. You name it – I bought them all, and rearranged the alphabet.” [11]

Hewison talks about the destructive power of Rupert Murdoch and other media barons at the time. Even today the UK has been relentlessly plagued by the Murdoch empire, which a couple of years ago accidentally revealed its true colours forcing a decision to close the News of the World paper when it found itself at the centre of a phone-hacking scandal. Employees of the newspaper were accused of engaging in phone hacking, police bribery, and exercising improper influence in the pursuit of stories [12]. Particularly damaging was the discovery by investigators that not only were the phones of public figures hacked- celebrities, politicians and British Royal Family members- but also the phones of private individuals, already innocent victims of public tragedies such as the murdered schoolgirl Milly Dowler and victims of the 7 July 2005 London bombings. The lives of us all are fair game as raw material for stories for the media markets.

Jubilee is one of those films that have so much in it and whenever I watch it again I always see something new. “The film originated in Jarman’s friendship with Jordan, the front woman for Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood’s most outrageous designs for Sex and then Seditionaries – and a punk icon. Jubilee included several punk groups in this state-of-the-nation address – Adam and the Ants, the Slits, Wayne County – marking the start of a fertile relationship with the music industry.” [13]

Revisiting Future Tense reminds us how influential and necessary punk was, and still is in creating the conditions for emancipation and artistic freedom. While postmodernism is able to describe and explain the workings of the postindustrial media ecologies it doesn’t create artistic agency. We don’t need it to make change. It’s main agency still remains within an academic framework. In contrast punk expanded beyond and reached the middle classes, but also included working class culture and influenced new forms of independent, collaborative and artistic expression.

“The credo that Anyone Can Do It reached a mass of individuals and groups not content with their assigned cultural roles as disaffected consumers watching the world go by. Like the Situationists, Punk was not merely reflecting or reinterpreting the world it was also about transforming it at an everyday level” [14]

Introducing dualities tends to force us into observing things with combative eyes and not as various levels of artistic engagements and situated knowledges. Of course, the other part of the story is artists’ use of technology and how this has a lineage in its own right. But, Future Tense is still relevant and all the more poignant because looking back reminds us how much creative imagination has been hidden, forgotten and lost by art institutions, galleries and art magazines, as they rely on the same historical canons, generation after generation. The last real social and Cultural Revolution, artistic evolution or even renaissance, was with punk. Although since the Internet we can now include glimmers of hope with Net Art and Tactical Media, and strands of hacktivism, early pirate radio and TV, and BBS’s. It’s obvious that corporations and their markets have wedged in their own yes men (and women) as troops to counteract and prevent the occurrence of another explosion of emancipation.

Ask yourself how many people working in the media or in the arts: the funding sector, art agencies, art galleries, art mags, art organisations, are from working class backgrounds? Where do the possibilities exist for actual artistic emancipation? All around me I see opportunities closing down and people closing the doors behind them; as the conditions imposed by the neoliberal 1% hoover up all of the resources, through the invention of Austerity measures. In fact, there are only a few artists and art organisations daring to even mention that neoliberalism even exists, self-censoring them selves so that their funding or jobs are not suddenly compromised. By going along with this we participate in killing our imaginations and artistic freedoms for expression now and in the future, dumbing everything down across the board. Don’t just take my word for it. Hewison’s latest book about culture and political policy published in 2014 Cultural Capital: The Rise and Fall of Creative Britain describes the impact of New Labour, targets, and an instrumentalised meritocratic ideology in the time of Cool Britannia and the 2012 Olympics and offers an in-depth account of creative Britain losing its way.

“It’s not a pretty sight, and his findings of folly, incompetence and vanity will entertain and disturb readers in equal measure. They should also embarrass any politicians and arts administrators who retain a degree of self-awareness.” [15]

Artists are now expected to be ‘AWSOME’, malleable entities. There is a pressure to try and get ahead of everyone else by repackaging one’s artistic intentions, ideas and behaviours under the (it’s obvious surely) ironic term innovation. This is so artists can morph to participate in a false economy that only accepts art to conform within the demands of a consumer, dominated remit. Thankfully, there are still grounded artists and networks of practice that understand the value to a wider culture of keeping their critical faculties sharp and experimenting with other ways to create, distribute and appreciate culture in the network age.

To end this short journey, I will leave you with a note from the conclusion of Future Tense– “[…] within the gaps and cracks of the present culture there are possibilities for renewal. Join up the cracks, and a network forms; follow the lines, and a new map appears. It points beyond the post-Modern.” Good advice….