This article revisits Robert Hewison’s book, Future Tense: A New Art For The Nineties, [1] published in 1990. The book focused on contemporary attitudes to art, architecture and design that manifested in what had come to be called the postmodern era. Earlier avant-gardes of collectives and groups such as Dada, Situationism, Fluxus and the Lettrists had incorporated new technologies and challenged the material values embraced by museums and traditional hierarchies in modern art and capitalist society. Hewison set out to discover the ways in which artists of the 80s contributed to a “critical culture” for the 90s. [2]

In the 70s in the UK, art had a role to play in changing society, transforming relations to controlling production and critiquing the role of the establishment. Hewison’s mission was to observe contemporary culture happening in the late 80s in Britain with an emphasis on the future. Even though there had been a massive evolution in culture; within and across the fields of music, art and theory, it was also a new dawn for capitalism as it morphed into what we now know as neoliberalism. By revisiting Hewison’s book I hope to elucidate what the cultural shifts and differences in our art culture then and now are, and invite you the reader to reflect on what they mean to those of us engaging with and practicing across the fields of art, technology and social change today.

The way Hewison deals with postmodernism and its rapport with art and society is complex. He appears to regard much of the established art promoted in the late 80s, such as works by Jeff Koons, as banal marketing schemes, appealing to the interests of a privileged art-buying elite. He is more positive about grass roots communities re-appropriating and remixing art culture for others to claim on their terms. Michael Archer in his review of Present Tense in Marxism Today (1990) observed that not only was Hewison critical of modernism but also of postmodernism, which did little more than signal modernism’s ending. [3]

![[4] (Hewison 1990)](http://www.furtherfield.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/hewison1.jpg)

Lyotard argues that the grand narratives of 20th century modernism did not produce the benefits expected; rather, they have led to overt or covert systems of oppression. From this perspective the French Revolution and classic Marxism are seen only as forms of overarching and oppressive, ideology. Frederic Jameson offers another perspective on the ideas and social contexts around postmodernism. In his book Postmodernism: Or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism, Jameson says “It is safest to grasp the concept of postmodernism as an attempt to think the present historically in an age that has forgotten to think historically in the first place.” [5]

Future Tense’s cover image on the front of the book still feels contemporary. It shows a young woman about to kiss her mirror image while in front of a cracked glass, window. It alludes to a sense of culture – felt then as we still feel it now: as a disjointed picture of the world where modes of thinking and representation show us fragmentations, discontinuities and inter-textuality, and ‘bits-as-bits’ rather than unified objects. If the image were created now with a smashed up computer or mobile phone screen or an interface, its message would not be so different. We tend to beam our faces at our computer screens and then the screens beam right back at us, reflecting at us like data-mirrors, showing back not only a distorted image of ourselves but also a distorted multiverse.

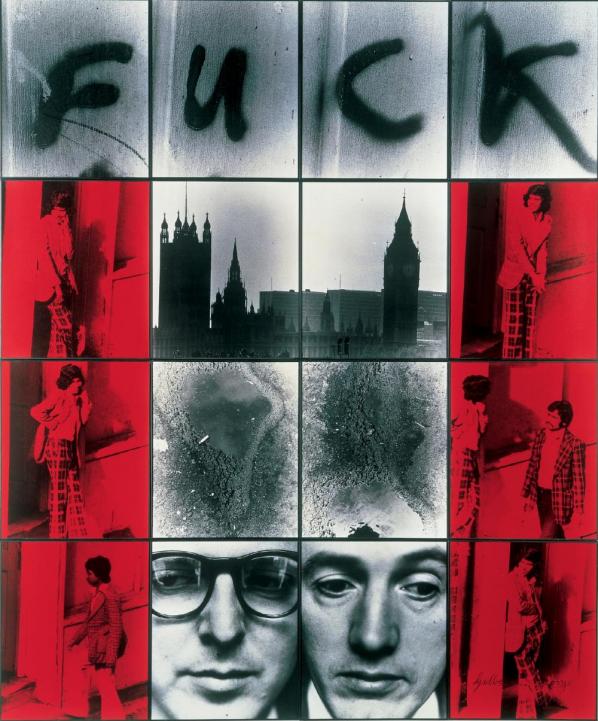

There has always been an irony at play with Gilbert & George. They usually expound a kind of punk aesthetic as an edgy chic; your lowest, basic, bigoted and unreconstructed inner ape giggles at their poo jokes. Yet while they subvert the idea of the ‘high’ of ‘high art’ by breaking life-style taboos they never bite the ‘high’ hand that feeds them. They know that shock is a dead cert currency just as the gutter press understands that sex and outrage sells, and that ethics and criticality get in the way of free market play. They sit well with the younger establishment in the arts, especially Damien Hirst and his peer YBAs, and similar Saatchi and Saatchi marketing investments.

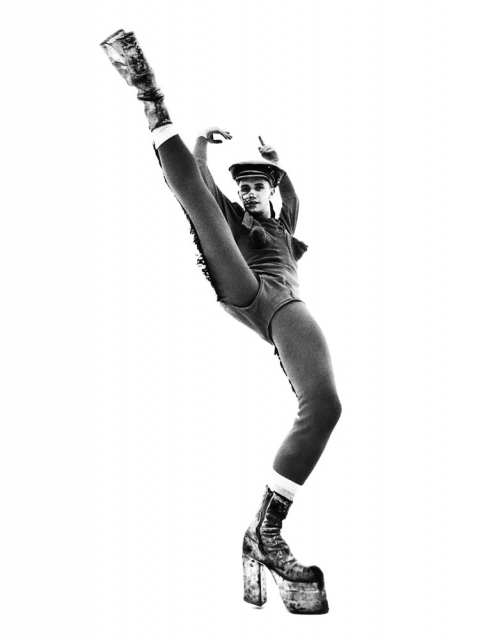

Hewison discusses Saatchi and Saatchi’s gallery space, and how the work presented in the space achieves an apparent purity, which detaches it from life, and that it has that autonomy within its own sphere which much twentieth-century art has sought to achieve. But in doing so it has separated itself from that other impulse, to use art as a means of revisualising, and so changing the world. [6] (Hewison 1990) This is still a big problem with art across the board even now. Most art agencies, orgs and galleries, are still separated from people’s everyday life experience. In contrast Michael Clark and his dance company was and still is a breath of fresh air. Even though he was classically trained, Clark tore “up the conventions of ballet, mixing sound and image in a rapid collage of creation, quotation and reference that plunders popular culture with calculated offence.” [7]

Cross cultural and interdisciplinary collaborations have been another marker of radical transformation in the postmodern era. Clark’s collaboration with the punk band The Fall in 1988 is a case in point where two different fields meet and create a brilliant outcome.

“I’ve always had a very strong relationship to music, to punk and pop – David Bowie, Iggy Pop, Sex Pistols, especially The Fall. The Fall’s song “New Puritan” was kind of a clarion call to me, not just because its rhythm is so ramshackle. When you listen to it, you wonder, “How the fuck do the musicians stay together?” Apart from that, the song encouraged me to say, “Wow, I’ll do it just like Mark E. Smith!” You know, “New Puritan” was against the idea of a big company, and I didn’t want to be employed by anyone. I didn’t want to sign a contract. I wanted to make my own work. I wanted independence, my own company. Mark E. Smith was definitely an example for that.” [8] (Clark 2014)

Many women artists during the 80s and 90s were using their bodies and identity as part of their art practice. Perhaps, one of the most treasured in the UK and greatly missed is Helen Chadwick who died on the 15th March 1996.

“Long before the current artistic obsession with the human body as a means for exploring identity, Chadwick had declared that “my apparatus is a body x [multiplied by] sensory systems with which to correlate experience”” [9] (Buck 1996)

Yet, her work resonates beyond her time period and still lives on through individuals inspired by her imaginative works to this day. Hewison dedicates five pages to Chadwick, and when discussing her installation Of Mutability, he says her work possessed a particular autonomy and, “Chadwick has found that the piece is most quickly appreciated by bisexuals who apprehend more easily the polymorphous nature desire.” [10] (Hewison 1990)

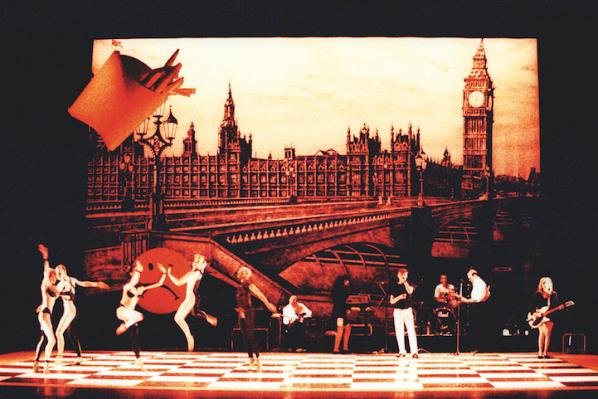

Hewison refers to the media baron Cardinal Borgia Gint in Derek Jarman’s film Jubilee, the baron in the film says “You wanna know my story, babe, it’s easy. This is the generation of who forgot how to lead their lives. They were so busy watching my endless movie. It’s power, Babe. Power. I don’t create it, I own it. I sucked and sucked and sucked. The Media became their only reality, and I owned the world of flickering shadows – BBC, TUC, ATV, ABC, ITV, CIA, CBA, NFT, MGM, C of E. You name it – I bought them all, and rearranged the alphabet.” [11]

Hewison talks about the destructive power of Rupert Murdoch and other media barons at the time. Even today the UK has been relentlessly plagued by the Murdoch empire, which a couple of years ago accidentally revealed its true colours forcing a decision to close the News of the World paper when it found itself at the centre of a phone-hacking scandal. Employees of the newspaper were accused of engaging in phone hacking, police bribery, and exercising improper influence in the pursuit of stories [12]. Particularly damaging was the discovery by investigators that not only were the phones of public figures hacked- celebrities, politicians and British Royal Family members- but also the phones of private individuals, already innocent victims of public tragedies such as the murdered schoolgirl Milly Dowler and victims of the 7 July 2005 London bombings. The lives of us all are fair game as raw material for stories for the media markets.

Jubilee is one of those films that have so much in it and whenever I watch it again I always see something new. “The film originated in Jarman’s friendship with Jordan, the front woman for Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood’s most outrageous designs for Sex and then Seditionaries – and a punk icon. Jubilee included several punk groups in this state-of-the-nation address – Adam and the Ants, the Slits, Wayne County – marking the start of a fertile relationship with the music industry.” [13]

Revisiting Future Tense reminds us how influential and necessary punk was, and still is in creating the conditions for emancipation and artistic freedom. While postmodernism is able to describe and explain the workings of the postindustrial media ecologies it doesn’t create artistic agency. We don’t need it to make change. It’s main agency still remains within an academic framework. In contrast punk expanded beyond and reached the middle classes, but also included working class culture and influenced new forms of independent, collaborative and artistic expression.

“The credo that Anyone Can Do It reached a mass of individuals and groups not content with their assigned cultural roles as disaffected consumers watching the world go by. Like the Situationists, Punk was not merely reflecting or reinterpreting the world it was also about transforming it at an everyday level” [14]

Introducing dualities tends to force us into observing things with combative eyes and not as various levels of artistic engagements and situated knowledges. Of course, the other part of the story is artists’ use of technology and how this has a lineage in its own right. But, Future Tense is still relevant and all the more poignant because looking back reminds us how much creative imagination has been hidden, forgotten and lost by art institutions, galleries and art magazines, as they rely on the same historical canons, generation after generation. The last real social and Cultural Revolution, artistic evolution or even renaissance, was with punk. Although since the Internet we can now include glimmers of hope with Net Art and Tactical Media, and strands of hacktivism, early pirate radio and TV, and BBS’s. It’s obvious that corporations and their markets have wedged in their own yes men (and women) as troops to counteract and prevent the occurrence of another explosion of emancipation.

Ask yourself how many people working in the media or in the arts: the funding sector, art agencies, art galleries, art mags, art organisations, are from working class backgrounds? Where do the possibilities exist for actual artistic emancipation? All around me I see opportunities closing down and people closing the doors behind them; as the conditions imposed by the neoliberal 1% hoover up all of the resources, through the invention of Austerity measures. In fact, there are only a few artists and art organisations daring to even mention that neoliberalism even exists, self-censoring them selves so that their funding or jobs are not suddenly compromised. By going along with this we participate in killing our imaginations and artistic freedoms for expression now and in the future, dumbing everything down across the board. Don’t just take my word for it. Hewison’s latest book about culture and political policy published in 2014 Cultural Capital: The Rise and Fall of Creative Britain describes the impact of New Labour, targets, and an instrumentalised meritocratic ideology in the time of Cool Britannia and the 2012 Olympics and offers an in-depth account of creative Britain losing its way.

“It’s not a pretty sight, and his findings of folly, incompetence and vanity will entertain and disturb readers in equal measure. They should also embarrass any politicians and arts administrators who retain a degree of self-awareness.” [15]

Artists are now expected to be ‘AWSOME’, malleable entities. There is a pressure to try and get ahead of everyone else by repackaging one’s artistic intentions, ideas and behaviours under the (it’s obvious surely) ironic term innovation. This is so artists can morph to participate in a false economy that only accepts art to conform within the demands of a consumer, dominated remit. Thankfully, there are still grounded artists and networks of practice that understand the value to a wider culture of keeping their critical faculties sharp and experimenting with other ways to create, distribute and appreciate culture in the network age.

To end this short journey, I will leave you with a note from the conclusion of Future Tense– “[…] within the gaps and cracks of the present culture there are possibilities for renewal. Join up the cracks, and a network forms; follow the lines, and a new map appears. It points beyond the post-Modern.” Good advice….