In her work, using video, performance and the Internet, Annie Abrahams questions the possibilities and the limits of communication, specifically its modes under networked conditions. A highly regarded pioneer of networked performance art, Abrahams brings her academic training in both biology and fine arts to develop what she calls an aesthetics of trust and attention. She creates situations that “reveal messy and sloppy sides of human behaviour” making that reality of exchanges available for reflection. We first worked with Abrahams in her exhibition ‘If not you not me’ in 2010 and then as part of a group show ‘Being Social’ 2012. In this interview we ask her to reflect on the limits and potentials of art and human agency in the context of increased global automation.

Catlow & Garrett: While predicated on the idea of connectedness, the global social media platforms are designed to profit the companies who create them and to keep billions of us in a state of trance-like immersion which has in turn been shown to cause many of us to feel more isolated. At Furtherfield we have always worked to grow more communal and collaborative contexts for artistic production. What does your current thinking – through your work on Participative Ethology in Artificial Environments: ethnological approaches to Agency Art – reveal for the potential of genuine, participatory networking environments?

Annie Abrahams: Participative Ethology in Artificial Environments: ethnological approaches to Agency Art sounds nice, but it needs a question mark at the end. It’s an interrogation. In times when our technological environment uses all kinds of behavioural techniques to make us uncritical users of their interfaces, it’s important to become aware of our behaviour, to test and experiment with it. My artistic work is based on doing that, but I always had great difficulties explaining it to art institutions etc.

A discussion I had with my friend Cor whom I studied biology with in the seventies, helped me find this latest description. I told her, that I think about my work as having human behaviour as its main aesthetic component and why I call it, silently, “behavioural art”. I compare what I do now to what I did when I studied biology. In both cases I observe behaviour in constrained situations. The monkeys, that were the study objects “became” humans and the cage the Internet.

Because the behavioural science of the late seventies didn’t suit me very well – using Skinner boxes, operant conditioning techniques and related to sociobiology, with a link to eugenics – it has become impossible to use this historically contaminated term. The wish to control, mold nature, and humans wasn’t mine. “Behavioural” was and still is a “stained” word for me. But even so, I do study behaviour and create constrained situations. I ask people to perform in a frame, they are framed in an apparatus, which is more or less perfect – the Internet provokes, lags, bugs, glitches, the computer is old or new, fast or slow, the interface determines how the performers can interact or not, the domestic situation interferes with noise and cats wanting to join in. There is a protocol/a script/a scenario but no rehearsal, just some technical tests. My approach is more phenomenological than scientific, I don’t measure anything. It’s up to the performers to explore their own behaviour, to reflect on it and to learn together what it means to be connected.

I told Cor, my annoyance with the tendency of art institutions to categorise art. Video art, poetry, contemporary art, literature, dance, painting, music and media art, computer art, code art, … It’s so impractical and superficial and it always takes a technology or a medium as its anchor point. It doesn’t say anything about what it makes possible, about what we can experience through it. Maybe that’s why I started to use the word performance, and performance art more and more. It’s a cross-discipline word. It’s multi purpose, but also a bit empty, I must admit.

“Agency Art is art that makes it clear to the receiver via his or her body what is at stake, where opportunities for action lie, and which virtual behaviours he or she can actualize. It demonstrates how choices work.” Arjen Mulder, The Beauty of Agency Art, 2012.

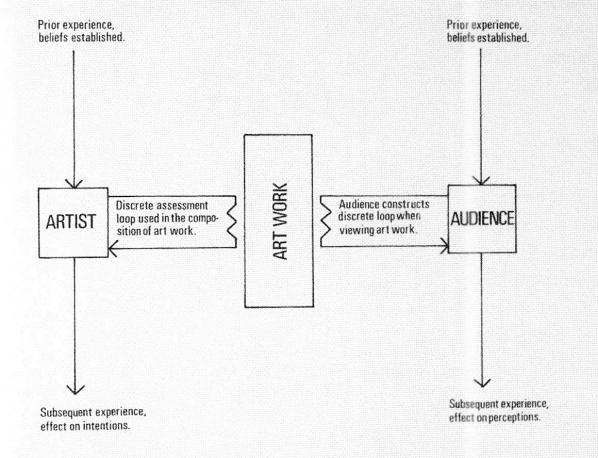

In his article The Beauty of Agency Art, Arjen Mulder uses the concept Agency Art to indicate interactivity as the important component of an art work. It is an interesting attempt to develop a discourse for technology/media art in relation to the contemporary art discourse. He embeds his ideas in history and goes back to thinkers such as: Shannon, Wiener, MacKay, McLuhan, Cassirer, Langer, Gell, Latour, Heidegger, Derrida, Badiou, Rancière, Danto, Whitehead, Steiner, Rolnik and more. I like the concept because it determines art that has behavioural choices and gestures as its centre. Its meaning is the acts that are made possible. What is also important in Mulder’s reasoning, is the concept of “virtual feeling”, introduced by the philosopher Susanne K. Langer in her groundbreaking book Feeling and Form (1953). Langer explains how each individual art medium evokes, manipulates and investigates “virtual feelings” in its own way.

“A painting calls forth virtual depth with lines and colours; a sculpture constructs a virtual volume around itself; a novel constitutes virtual memory, tracked through virtual time. Dance follows virtual forces of attraction and repulsion. All the experiences that are part of this “feeling” are spaces of possibility, virtual feelings waiting for actualization; their nature, allurements and dangers must be studied, and art is where this investigation takes place” Arjen Mulder, The Beauty of Agency Art, 2012.

This is how to think of behaviour as an aesthetic force, I told Cor. This is a concept that I can use to talk about what is important to me. For me, the words are empowering and stimulating, pointing to Butler, ANT theory and Karen Barad, I cannot and won’t leave them behind me.

collectively made – refusing hierarchy- a knitting together of artists and performers in the moment of the event – erasure of the artistic ego – practice – changing rules – choices – connecting – accepting the unexpected – responsive – shared – collaboratively authored – open to all – working with temporal behavioural phenomena – healing – enactment – improvised – including environmental conditions – attentional strategies – instructions – protocols – apparatus – meeting – embracing the ordinary – rehearsing alternatives – re-hijacking therapy – exercising our relations to others – our social (in)capacities – exploring rituals – being together – participatory – concerns individuals and politics

These are keywords found while researching work (from fine art, dance, theater, music, performance, digital art to electronic poetry) I could consider being Agency Art : Deufert&Plischke’s work, LaBeouf, Rönkkö & Turner’s HEWILLNOTDIVIDE.US, Building Conversation by Lotte van den Berg, Deep listening by Pauline Oliveros, Poietic Generator by Olivier Auber, Lingua Ignota by Samantha Gorman and Walking Practices by Lenke Kastelein.

Using Agency Art also means being able to make cross sections through disciplines and to open up closed domains of practicing. And that is the moment in our conversation where Cor, who has also a degree in philosophy said : “It’s easy, call your work participative ethology in artificial environments.” I am still pondering and that’s why there has to be a question mark. There always have to be question marks.

#PEAE = #Participative #ethology in #artificial environments #ethnological approach #AgencyArt?

C&G: Katriona Beales drew our attention to the Kazys Varnelis’ essay in the Dispersion catalogue (ICA 2008) which talks about the concentration of power in nodes of connectedness. She says “So even if I write a response to Donald Trump’s tweet saying “I hope you’re impeached”, for example, I add to his power, just through the interaction. I end up contributing to his power base even though I explicitly disagree” This effectively rewards, with attention, those who inspire intense outrage, fury and derision. Interfaces play a crucial role in your network performances and deliberately prompt very different kinds of behaviour – we’re thinking in particular of Angry Women. What kinds of behaviours and responses does your work inspire?

AA: I agree the concentration of power in nodes of connectedness is disturbing and confusing. It puts us in a double bind situation, becoming petrified, unable to act or to flee because we can not choose. I think this might be true when we consider our role in big networks, but it is definitely different when we talk about smaller networks. There it matters what we say and especially how we say it. A big part of my work is to create situations / interfaces / performances that permit us to experiment and train our (un)capacities to do so in networked environments. Participating in one of my performances means taking risks – nothing is rehearsed, means accepting you can’t control everything, it means committing to continue even if all seems to go wrong, to be attentive to the others around you with whom you share the performance space, with whom you are co-responsible for the shared moment in time.

From the people watching I ask that they are aware of what is at stake in a performance. That they watch it not with a connoisseurs regard, but that they see it as an aesthetic experiment in which behaviour is the main aspect / asset. If they become sensitive they have access to a very intimate and fragile aspect of our being, to something we absolutely need to discover further if we want to escape an allover binary future.

For myself I analyse the “concentration of power in nodes” phenomenon as the result of something you could call a lack of res-ponsability in our online affect management. When you are always scrolling you are unaware of the reaction you provoke, you are not awaiting a reply, but already on the next, next, next photo or short text. There is very little interactivity, and even less exchange. We act without caring for what our words, actions, and ideas bring forth. We might not be aware but our words, actions, and ideas live beyond us, they do intra-act with the actual situation. They are things acting in a world. (**)

** I have been reading texts on intra activity, a neologism introduced by the physicist, and feminist theorist Karen Barad. It’s difficult stuff. This video (Written & Created by: Stacey Kerr, Erin Adams, & Beth Pittard) gives easy access to one of her most important points.

C&G:

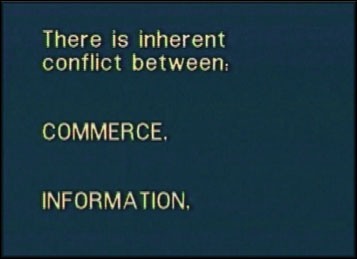

Yes, it is now totally normal to refer to “people” as “consumers”, every organisation an “enterprise”, which in turn leads to proposals for the nation-as-a-service, populated and run in the interest of private enterprise as offered by the e-stonia bitnation project.

By accepting the impoverishment of experience and reduction in agency implied by this label we can forget about ourselves as “actors” in the world, and become the cattle of the few. The only agency we are offered is as a responsible consumer (in which our powers are reduced to a binary option to buy or not). This is the new democracy.

In the UK these days, art audiences are often described as “consumers”. How else in your view might we conceive of “audiences”. What agency might we wish for them. And what part might our relationship with devices and digital networks play in this new description?

AA: We are not yet used to machines reacting to and using affects, tapping into our endocrine system. Articles like “Our minds can be hijacked’: the tech insiders who fear a smartphone dystopia” make us more and more aware of how we are manipulated and distracted, how our attention is designed, guided, influenced, used. But a lot of it is still hidden and because it’s so rewarding and because we “need” the attention we continue to click and vote. It is possible to create environments where people can slow down and have more subtle, nuanced agency, where they can participate and become aware and reflect on of their own behaviour. DIWO projects for instance have that power. People, especially art lovers, can be challenged to engage with others in interesting actions and conversations.

With Daniel Pinheiro and Lisa Parra in Distant Feeling(s) we invited the audience to join us in an experiment where we share an interface, normally used for online conferencing, with our eyes closed and no talking allowed. It led to very diverse observations shared via social media and email exchanges: liminal space – pure motion – an intimate regard – a field of light – dissolved, destabilized – an altered state – a telematic embrace – a silent small reprieve – hanging out with friends – machines conversing across the network only when the noisy humans finally shut up – an organic acceptance of silence?

Keywords from the reactions : http://bram.org/distantF/

Distant FeelingS #3 | VisionS in the Nunnery – Oct5-Dec18 2016

C&G: Unlike technologies and forms of production that work in the area of speculative realism, automation and AI, you still place humans and human relations at the centre, how do you view the current moves to shift agency away from humans into these ranges of techno-social systems?

AA: I am particularly intrigued and troubled by what is called deep learning. The algorithms produced by the machines themselves have a big influence in and, we must be honest, potential for for instance the health care business. They also determine on what moment of the day, depending on your mood you will see which advertisement on your device. As explained in The Dark Secret at the Heart of AI nobody can really understand how these applets produce their outcome – not even the programmers who build them.

For me this is problematic. Algorithms cannot invent what didn’t exist before and so they tend to reproduce / to select more of the same / to reinforce the existent. (see deep dream images) Moreover a lot of deep learning is based on the algorithm learning to produce a desired outcome.

As the machines are also designed to make us ready for their coercion, we are already subconsciously, intuitively adapting to these black box processes. We need to try to understand how these processes influence us, not because they are necessarily bad, but because our interests might not always coincide, we might want to differ. We don’t all have to learn programming the machines. That has become far too complicated and specialist and maybe not the best route to take. But we could engage in projects who try to find out how to influence machine behaviour, how to keep some agency. Maybe by introducing noise and entropy into the processing, so, together with the machines we can continue to cherish difference and diversity.

C&G: This question connects with the previous one. How do you see the role of artists in finding ways to negotiate a healthy relationship between artistic agency and capital-driven-machine worlds?

AA: This is a very difficult question to which every artist has to formulate her own answer. But it for sure passes by trying to open up spaces and discussions with people who have other opinions than yours, to going beyond safety-zones, to finding ways to communicate with and about hatred, angst and love.

*——————–*

This editorial series, takes digital addiction as its theme, and sits alongside the Are We All Addicts Now? exhibition, book, symposium and event series, we are hosting at Furtherfield. Are We All Addicts Now? Is an artist research project led by Katriona Beales and has been developed in collaboration with artist-curator Fiona MacDonald: Feral Practice, clinical psychiatrist Dr Henrietta Bowden-Jones, and curator Vanessa Bartlett. It looks at the application and impacts of many different research findings in the creation of digital interfaces, devices and experiences under the conditions of Neoliberalism.

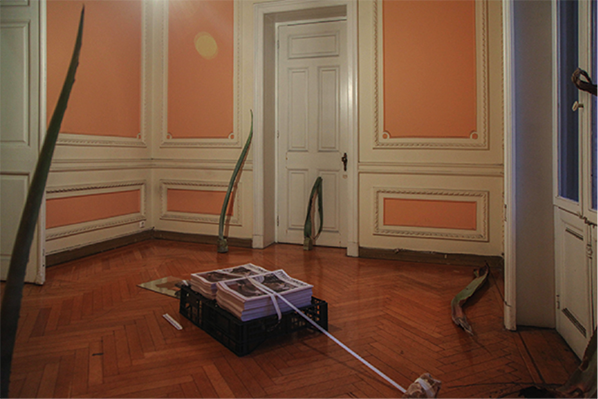

Walking off the Akadimias district and onto the steps leading up towards the entrance of building number 23, I am greeted by a large hall with high red ceilings. The hall is covered with lavish white and black dot marble, and there is a large staircase acting as a guide to the top floors of the manor-like building. This was the home for the Diplomatic Centre of the Third Reich, designed in 1923 by Vassillis Tsagris, and used until 2011 by the Foreign Press Correspondent Union after the Second World War. Since then it has stood derelict and dusty, but for one week, in parallel to the opening of documenta 14, it played temporary host to the artist-in-residence programme of Palais de Tokyo, alongside with Foundation Fluxum/Flux Laboratory, bearing the name Prec(ar)ious Collectives. Six visual artists in residence at Pavillon Neuflize OBC and eight contemporary Greek choreographers envision and fabricate a hybrid space whereby an experimental notion of a community is executed as a situation rather than as a subject. The visual artists and performers involved congregated together in Athens and on site for a two-week workshop in March in order to produce the works. The title, Prec(ar)ious Collectives, is a linguistic amalgamation of the adjectives ‘precarious’ and ‘precious’, implying the state of the collective that performs together.

The opening façade echoes with the humming and reverberated sound of Manolis Daskalakis-Lemos‘ Dusk and Dawn Look Just The Same (Riot Tourism), guiding us towards its installation room. The video installation stands above a mountain of blue powder in a room sectioned off with construction tape. The short sequence of about a minute and a half displays a group of hooded figures, dressed identically. As the soundtrack’s volume begins to escalate, the group progresses from walking to running on the uncannily void and ghostly streets of Athens. A city always bustling with noise is now at its most quiet and pubescent state of the day – dawn. The hooded figures run together and – even though it is in a disordered manner – command your attention and pensiveness until they all reach Omonia Square. The work demonstrates a resistance to a status quo which may be aligned with the political engagement within the city. This is not, however, done in an expected reactionary manner, but instead in a way that promotes uprising through the creation of a meditative state. One cannot help but watch Lemos’ work a couple of times more before leaving it behind and only then noticing the thundering beneath their feet.

This historic building has a basement and is the temporary home of Taloi Havini‘s performative work. The large-scale installation occupying four rooms consists of PVC vinyls, seemingly discarded or hung from the low ceiling. These PVC vinyls are lit by dispersed and differently coloured strings of light, some are red, others are purple and others are cream. The performance is underway and its performers dress themselves with the PVC vinyl and the lights and jolt their bodies vigorously to the rhythm of the thundering – sometimes in sync, sometimes not. The dark basement is transformed into a cavern of rhythmic delight alluding to a ritual where its power lies in the gathering of people.

As one inspects the garments of Wataru Tominaga and those who wear them, this synthesis of the PVC, the space and the performers as a gathering appears to be a motif. Tominaga created the garments during a preliminary workshop, with great care and appreciation of how he and others were to utilise them during Prec(ar)ious Collectives. Originally presented on mannequins before being worn and performed, the garments boast vivid colours and patterns, some of them containing animalistic features such as feathers or fur. Those who wear Tominaga’s work perform in such a way as to invent a new form of communication between themselves and their observers. They move and conjoin like animals, sometimes hiding underneath the fabric and at times evoking the traditional Japanese ‘snake dance’. The performance, being in a transitional space between the ground floor and the first floor, naturally spreads itself upstairs whereby the performers not only continue to wear the garments in obscure ways, but additionally interact with Yu Ji‘s agave plants and other objects.

Yu Ji‘s work, Lycabettus Tongue, Oliv Oliv and This is Good For You! Are formed by the use of displaced agave plants, half-fragmented found mirrors and lights. The agave plants interlock with various architectural patterns of the building such as stair banisters, whilst the mirrors and round-ball lights are positioned in ways offering various points of view for observation and appreciation of space. The work revitalizes the architecture of the building denoting its historical vitality and the synergy of the encompassing works into a haunting existence rather than an abandoned one. Here, haunting is used not for means of negative connotations but instead as a form of aloof yet introspective sensation, exasperated further with Lola Gonzàlez‘s video installation in the next room.

Lola Gonzàlez‘s Now my hands are bleeding and my knees are raw begins with its protagonists split into groups and observing the city of Athens from various points at the top of the hills. The groups begins to move, run and hop together towards a direction down the hill, whilst a chorus of droning voices begin to chant and harmonise. As the groups get closer and closer to the city, Gonzalez transforms the image into a complete inversion, like one you may find in negative photography. The chanting becomes louder as the three groups get closer and closer to their meeting point within the city – the exact space where the video is being showed. They are finally shown entering the building and making their way up the stairs to the room where they vocalize in unison until they fade away from our view. Now my hands are bleeding and my knees are raw alludes to an atmosphere in which the power of gathering together evokes a community whose intention is situated between an uncertain balance of peril and strength. It is the same kind of uncertainty that one finds when exploring the top floor of the building only to discover Thomas Teurlai‘s room of machines and looped functions.

On the top floor, there are still the remnants of neglect, rooms empty of anything but the garbage that piled up over the building’s six years of desertion. Thomas Teurlai‘s Score for bodies and machines consists of a room installation of two printers used by the performers to scan different parts of their bodies. These scans are then plastered on the wall whilst the fluorescent lights constantly trickle on and off. The two performers are attempting to archive as much of the movement involved in their choreography as possible. The looped function of copying and the crackle of its repetitive working-noises do not clash with the choreography but instead drive its energy.

Indeed, it may be the encounter between the building, the communal working spirit of the performers and the result of this effort that defines this rejuvenating energy as a fruitful rebirth of the building’s utility.

To find out more, read Chloe Stavrou’s recent interview with Fabien Danesi of Prec(ar)ious Collectives.

CS: Tell us a little bit about how the collaboration between Palais de Tokyo’s residency Pavilion Neuflize OBC and Fluxum/Flux Laboratory came about. Did this directly contribute to the hybrid of visual/dance performance art or was it the artists’ call?

FD: During two years, the Pavillon Neuflize OBC has worked with the National Opera of Paris for projects at the crossroads between contemporary art and choreography. We wanted to develop this perspective which is a kind of tradition in the history of the Pavilion (created in 2001), if we remember that our institution has a long interest for transdisciplinarity. So the hybridization between visual art and performance wasn’t the artists’ call. On the contrary, we asked them to step aside for collaborating with choreographers. It was really experimental for them.

CS: Neither Palais de Tokyo or Fluxum/Flux Laboratory are situated in Greece. What was the reason for its inception to take place in Athens? Was it because of the traffic Athens would see due to documenta 14 or was it a suggestion by Andonis Foniadakis, the choreographic director?

FD: Since its creation, Fluxum/Flux Laboratory has developed many dance projects in Greece. And it’s due to its founder, Cynthia Odier, that Ange Leccia and myself met Andonis Foniadakis. We started the dialog with Andonis right at the moment of his nomination as the Ballet Director of the Greek National Opera, o Athens appeared quickly as the perfect place for our collaboration. We decided just afterwards to take advantage of the presence of documenta 14 in the city.

CS: The result is quite impressive – specifically since, and correct me if I’m wrong – the work produced was created in only two weeks in March. How did you find the process of working and creating collaboratively in addition to being in an unfamiliar city?

FD: The residents came to Athens for the first time in November 2016. During the first week, we had met the choreographers and dancers but also people who are engaged in the artistic life of the city. We tried to understand and use the pulse of this specific urban energy. We visited some sites for the exhibition and began to question the relevance of our own presence here. The conversations with the choreographers permitted us to create a strong link with Athens and not feel like tourists. We came back for a three-week workshop in March, just before the opening of our show. Between these two stays, we discussed a lot and had decided to start from our situation with the desire to move away from an artificial subject. The notion of the collective seemed a good way of taking charge of what we tried to do – especially because the Pavilion tries every year to create a specific group that gives a specific form to its structure.

CS: Prec(ar)ious Collectives feels like it could be quite nomadic as it is in an unfamiliar environment; however nomadic does not mean it feels odd or out of place – in fact it felt quite the opposite. As a curator, how did you approach Athens and stay conscious of the context(s) surrounding it?

FD: The fact that we didn’t exhibit in a white cube or an artistic space helped us. When we decided to occupy this abandoned building on Akadimias Street, I was sure that we would be related strongly to the city and its history. The context wasn’t outside of the walls – it was here, with us. Of course, we were all conscious that we needed to stay in relation to what was happening in the city. That’s why nobody arrived with their work completed and done. The materials and the main elements of the creations were an artistic answer to this particular context.

CS: I am very curious about the building. I understand it used to be the Diplomatic Centre for the Third Reich during the Second World War. How did you become aware of its existence, and did your decision to curate Prec(ar)ious Collectives have anything to do with the building’s history? If not, what was the reason for selecting this building?

FD: In January 2017, the director of the Pavilion Ange Leccia was in Athens to present some of his work. He visited the exhibition organized by Locus Athens in this space and it impressed him quite a bit. We wanted to work in an abandoned site for underlining the economical and cultural situation in Greece. And Akadimias Street 23 seemed perfect. We didn’t choose it for its history, even if these multiple layers added some density to our proposal. For sure, the different atmospheres of the rooms immediately gave us the possibility to create dialogs between the works while preserving the integrity of each. So, it was a question of ambience in the sense of the architectural conditions aiding the experience of the audience.

CS: I found that a continuous theme within the exhibition was not only the creation of a utopic community, but also an ambience that generates a state of limbo – of transition. Was this a reference to the state of Athens or to the state of artistic production or work?

FD: The notion of limbo is stimulating. And it insists on our «spectral approach». It means that we have tried to give life to this abandoned building. And some installations can be described as floating. In Manolis Daskalakis-Lemos and Lola Gonzalez’s videos, for example, there is the idea of apparition. And even with Taloi Havini’s huge ephemeral camp, we can feel a sort of «in-between» space, archaic and futurist, protective and dangerous. Maybe it was a re-transcription of our impressions about Athens, so appealing and full of energy, but at the same time, so undermined by the political situation.

CS: As a final note, what is the next step for Prec(ar)ious Collectives after its brief residency in Athens? Are there any plans to simulate the experience, albeit differently, again in another context or place?

FD: There won’t be another step for Prec(ar)ious Collectives as a group exhibition. It was really the result of a one-month workshop. But it happens for the best that some encounters initiated in the Pavilion can be developed after the time of the residency.

CS: And any future projects that you will be a part of?

FD: On my side, I will develop a curatorial project next year in Los Angeles in the frame of FLAX residency. Titled The Dialectic of the Stars, I will organize several evenings in different institutions which will permit artists? to drift in the city from one site to another for catching some contradictory parts of the L.A. atmosphere. The idea is to mix French artists and Los Angeles-based artists and to trace a political and poetical constellation.

To find out more read Chloe Stavrou’s recent review: Community Situation: Prec(ar)ious Collectives and documenta 14

Feature image:

Trust Me, I’m an Artist: Jennifer Willet and Kira O’Reilly, Be-wildered, 2017. Photo: Nora S. Vaage

Trust Me, I’m an Artist is an exhibition organized in cooperation with the Waag Society at Zone2Source’s Het Glazen Huis in Amstelpark, in the outskirts of Amsterdam. It is a culmination of a Creative Europe-funded project, aiming to explore ethical complexities of artistic engagements with emerging (bio)technologies and medicine. The explorations in the exhibition have taken place through a play on the format of ‘the ethics committee’. In university contexts, particularly within medicine and the natural sciences, researchers need to submit their proposals to ethics committees to check whether their proposed projects comply with the relevant ethical guidelines, and to point to any issues the researchers hadn’t thought of. In the last couple of decades, as artists have increasingly taken part in institutional settings, even becoming residents in scientific labs, they too have sometimes been faced with these committees. The Trust Me, I’m an Artist project has included a handful of artists’ proposals to ethics committees, performed in front of an audience. Some of the exhibited pieces are documentation from those events, and are aesthetically somewhat unfulfilled. As thought-provocations, however, they still work.

Het Glazen Huis is, indeed, made mostly from glass, which creates the effect that the park outside enters into the exhibition room. For this exhibition it seems fitting, as the artworks deal, in various ways, with living things. While one of the pieces, Špela Petrič‘s Confronting Vegetal Otherness: Skotopoiesis, focuses directly on plants (more on that later), the only direct conversation with the green exterior is a pile of soil, generously run through with green specks of glitter, crowned by a striking headpiece topped with tall green feathers, which seems to mirror a fern plant of about the same height on the other side of the glass wall. The soil/hat construct is paired with a strange frock, constructed from old labcoats, but with frills and a cut resembling a 17th century garment, and far from white. The front and back of the coat is decked with transparent orbs, resembling snow globes. Each of them contains a different set of microbes, placed there through various acts of swabbing the environment or asking artist colleagues for donations in the form of mucus.

The frock and the soil concoction are the remnants of a performance by Jennifer Willet and Kira O’Reilly, which took place at the Waag Society the night before the exhibition opening. Willet was wearing the repurposed labcoats, O’Reilly the green headgear and a sparkling green dress inspired by drag and camp aesthetics. For much of the three-hour event, they talked about trust: what does it mean to trust? Do these artists trust themselves? O’Reilly stated that she is not sure she even values trust that much. They shared stories about their previous work, toasted with champagne, and interspersed their conversation, gradually, with elements of a “project proposal”.

O’Reilly, with Willet’s help, coated her arms in whisked eggs, as a base for green glitter. She showed examples of previous performances she had done using such glitter, often in the nude and sometimes involving fertilized chicken eggs. An hour into the performance, Willet revealed that her garment had been buried in soil at a conference, where people were encouraged to do stuff to the soil over the week: composting, urinating, etc, which explained the coat’s uneven, brownish tint. Only towards the end of the performance did she tell us that the globes were repurposed bowls made into “petri dishes”, filled with agar and ready to serve as a growth medium for various microorganisms. She then swabbed the jacket, swiping it onto the agar in one of the bowls, then swabbed O’Reilly’s nose. Willet proposes to wear another coat in the laboratory for a year, exposing it to various microorganisms, and to also wear it at home around her twin daughters, reflecting on how we large mammals serve in any case as carriers for all sorts of microbes. The ethics committee considered this a risky and unlikely aspiration, and did not think she would be allowed to go through with it. They did, however, encourage her to consult with them in developing her idea. A similar response was given to O’Reilly, who wants to cover a pine tree in Finland in glitter, reflecting on how her use of glitter is contributing to plastic pollution, and to work with a dead farmed salmon that she would get directly from a fish farm in Norway. At the end of the performance, O’Reilly unfolded a plastic sheet, spread three bags of soil onto the plastic, poured a bowl of glitter on top, and mixed it with her hands in a languid, beautiful way. She fetched a gutted whole salmon from a fridge, sprinkling glitter on it as well. Both of them, thus, did part of what they are proposing to do for their project already during the “ethics consultation”, challenging the format. But they reflected at the close that the opportunity to think extensively on the ethics of their ideas was rewarding and important.

Martin O’Brien‘s Taste of Flesh – Bite Me I’m Yours is also documentation of a performance, which he did in London at Space c/o the White Building, in April 2015. His performance was an exploration of endurance, pain, and the overstepping of intimate boundaries. Working with his own body, O’Brien seems to have embraced the facts of living with a genetic disorder, Cystic Fibrosis, to the full. The disease causes him to produce a lot of mucus, and be short of breath.

Over a number of hours, he did a series of actions; chaining himself, biting people, being bitten, coughing up mucus, crawling around in a way that was inspired by the zombie as metaphor for being sick. He played with the fear that interaction will result in contagion, and with S&M paraphernalia and the limits between pain and pleasure. In the exhibition we see the performance on a projection taking up a whole wall, and five small, parallel video screens showing different parts of the performance. Remnants of the paraphernalia he used are exhibited on a plinth. The films in part convey the intensity and some-time repulsion that the performance must have inspired.

Petrič’s work Skotopoiesis is less explicit, and perhaps less provocative to most. In the exhibition, we see a photograph of a field of cress, with the outline of a human shadow making the center cress paler than the rest. By standing in front of the field, preventing the light from falling onto the same spot for 19 hours a day, three days on end, she created a visible imprint of her body, through cress that grew to be longer and paler than the neighboring plants that got direct sunlight.

Plants do not follow same rules of agency as animals. We cannot easily relate to them, although some, such as trees, seem to have more presence and individuality. Grass, on the other hand, is impossible to think of as single entity. Often, as part of the ethics procedure, researchers are asked if they can use plants rather than animals, as current perceptions of what is ethical tend to exclude plants from our ethical consideration. Petrič wanted to challenge the committee with something anti-spectacular, where it would be difficult to see ethical issues. Through existing with plants, trying to conform to their timescale and mode of existence, but also modifying them through her very presence, she entered into a pensive engagement not just with the plants themselves, but with the ethics of our coexistence with them. This seems quite a timely, as recent studies show plants to have more sensations, reactions, and even abilities of communication, than has previously been thought. Given this, our disregard for the life of plants may be seen as a great ethical challenge.

Artist Gina Czarnecki and scientist John Hunt, in the piece Heirloom, created masks in the shape of Czarnecki’s two daughters’ faces, grown from their skin cells over glass casts. This, too, is shown on several video screens, as documentation of the actual installation of the bioreactors in which the masks were grown. The artist wanted to preserve her daughters’ youthful likenesses, and the idea led to the development of a new, simple set-up for three-dimensional cell growth. One of the tricky ethical issues here is that of the ownership of a child’s cells. As the girls’ parent, Czarnecki could herself consent to using their cells in this way. They were happy to participate at the time, but does this kind of artistic, experimental use constitute “informed consent”? At the opening, Czarnecki observed that her daughters, moving into their mid-teens in the three or so years since their skin samples were taken, had become less comfortable with being on display in this way.

The videos show fascinating glimpses of the process, footage of the masks inside the bioreactors, flashing shots of the daughters’ faces, and narrations by the key actors. At one point in the video, Hunt describes how he and two of his fellow researchers both came into the lab because they were worried about the skin cells being contaminated. Without having anything to do there, they sat together and watched over them. A rare admittance of the personal bonds that can be formed with cell cultures, and reasons for action that are far from the rational.

Howard Boland‘s Cellular Propeller is represented in the exhibition through a few sculptural elements and photos. The project started as part of his long-time engagement with synthetic biology, and his ambition was to work with living, moving cells, attached to inorganic structures, to play with the old idea that “If it moves, it is alive”. Originally he hoped to use heart cells from new-born rats, but this proved difficult. Instead, he ended up using his own sperm cells, which are much more easily available, and share the ability to move. He created coin-sized, wheel-shaped plastic scaffolds that the sperm cells can ideally attach to, serving as “propellers” to literally,move the human cells, although this does not happen in a predictable way. In the exhibition, we saw reproduced the little plastic scaffolds, but not with the cells “in action”.

With the change from heart cells to sperm, the connotations of the piece changed slightly; while the question of “what is living” remains, reproduction, birth and movement still being central to the piece, the use of sperm also brings in ideas about pleasure and the surplus production of cells through recreational sex. Through repurposing sperm cells for the mechanical task of moving these wheels, Boland shifts the discussion towards life without the basic “meaning” that reproduction conveys.

“Controlled Commodity” by Anna Dumitriu features a dress from 1941, also exhibited on a headless mannequin, and mended with patches containing gene-edited E. coli bacteria. An example of wartime austerity, the dress is CC41 – controlled commodity 41. Dumitriu stresses the fact that 1941 was the first year that penicillin was used, and unlike clothing, this was not a controlled commodity. Overuse of antibiotics over many years has led to the current crisis, with more and more bacteria becoming resistant to the antibiotics we commonly use.

Through participation in the Future and Emerging Art and Technology program, Dumitriu was an artist in residence in an Israeli lab, and worked with the much-hyped, much-discussed CRISPR-Cas9 technology. The use of CRISPR for gene editing is currently being presented as a much easier way to insert or remove genetic information. In this case, Dumitriu used it to remove a gene for antibiotics resistance.

When she had to create a repair fragment to patch the bacteria back together, she used the phrase ‘make do and mend’, an explicit reference to WWII history. Dumitriu grew the CRISPRed bacteria on silk, sterilized them, and sewed the E. coli patches onto the (somewhat moth-eaten) dress. In addition to the dress, she is displaying the plasmid created using CRISPR in a little glass vase, only covered with aluminum foil – and without having asked permission. In an identical glass vessel, little paper circles contain all the antibiotics in commercial use.

The piece is rich, complex, and daring. In editing the genome of E. coli bacteria to remove an ampicillin antibiotic resistance gene, Dumitriu is proposing a potential solution to the pervasive problem of antibiotics resistance, which might also be ethically problematic: such suggested solutions being “around the corner” might lead to less focus on discovering new antibiotics, or the sense that continued over-use can be maintained. Also, her insistence on exhibiting plasmids in the gallery is not high-risk (as far as we know, plasmids need some sort of shock effect to be taken up by bacteria), but it does seem a somewhat unnecessary exposure. Dumitriu’s CRISPR work will be discussed in a Trust Me… event at the British Science Festival in Brighton in September.

Open Care – Inheritance, by Erich Berger and Mari Keto, imagines a personal responsibility for nuclear waste, in the form of radioactive family jewellery that goes from generation to generation, in the hope that you might one day wear it. The jewellery is kept in a radiation-proof container, and for each generation that takes over its care, it can be tested to see if the radioactivity has gone down to a safe level, so that “the jewellery can finally be brought into use and fulfill its promise of wealth and identity or if it has to be stored away until the next generation” (quote from the exhibition catalogue). The jewellery box and low-tech tools to check its radioactivity are exhibited behind a glass wall. This thought experiment suggests that the unimaginably long timespans that it takes for radioactivity to subsist can be broken down into spans of time that we can relate to. The personal nature of such family jewellery creates an emotional narrative of very personal responsibility for the waste we produce.

The artistic license seems to be to challenge, stretch, and provoke, and indeed, the artworks in this exhibition both challenge and stretch our views on what responsibility means. So, can we trust what these artists are up to? One never knows, but through engaging in these extended conversations with the public and hand-picked committees, they do give us new grounds for reflection on ethics, trust, and responsibility in science, in society at large, and in art.

Note: I saw this exhibition during the opening, and some elements were still not up and running.

As part of transmediale’s opening night in Berlin, audiences were sat in front of three large screens and taken on a journey through the abstract infrastructures of the imminent ‘smart city’. Liam Young, a self-proclaimed speculative architect, narrated the voyage whilst beside him, Aneek Thapar designed live sonic soundscapes complementing the performance. For Young, the smart city is a space where contemporary anxieties are not only unearthed but increasingly multiplied. The smart city manufactures users out of citizens, crafting an expanse whereby the hegemonic grip of super-production evolves into a threateningly subversive entity. According to Young, speculative architecture is one of the methods of combating the city’s supremacy – moulding the networks within a smart city to facilitate our human needs within a physical realm. It is a means of becoming active agents in amending the future.

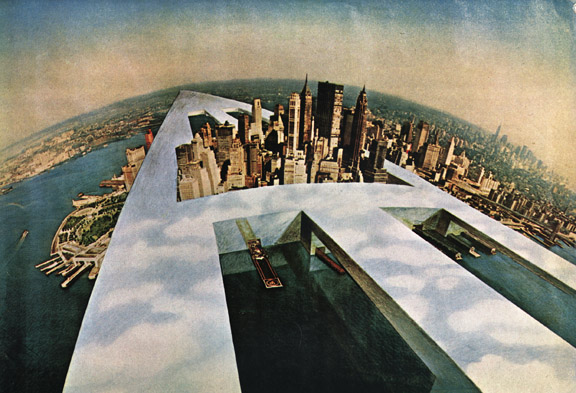

Speculative architecture as a term is relatively new, however the concept’s origins date back to the 1970s Italian leftist avant-garde. Back then it was called ‘Radical Architecture’, a term initiated by SUPERSTUDIO’s conceptual speculation regarding the structures of architecture. SUPERSTUDIO’s methods were transcendental as they favoured the superiority of mental construction over the estranged act of building. The founders of the group, Adolfo Natalini and Cristiano Toraldo di Francia, acknowledged modernist architecture as reductive to man’s ability of living a free life since its core foundations were built on putative methods of indoctrinating society into a pointless culture of consumption. The development of The Continuous Monument was a declaration to end all monuments since the structure itself was designed to cover the expanse of the world. Its function was to form ‘a single continuous environment of the world that would remain unchanged by technology, culture and other forms of imperialism’ as stated by SUPERSTUDIO itself. A function sufficiently egalitarian, and in some respects utopic, The Continuous Monument, much like Tatlin’s Third International in the 1920s, was never intended to be built, but instead to uncover the notion of total possibility and arbitrariness. Likewise, Young’s performative smart city does not purpose itself around applicable techniques of construction – it creates scenarios of possibility exploring the autonomous infrastructures that lie between the premeditated present and the predicted future. Hello City! intends to transpire the idea that computation, networks and the anomalies that surround them are no longer a finite set of instructions, but instead constitute an original approach to exploring and facilitating speculative thought through imagined urban fictions.

Liam Young’s real-time cinematic narration cruises us like a ‘driverless vessel’ through the smart city beyond the physical spectrum. The smart city becomes an omnipresent regulator of our existence, as it feeds on the data we wilfully relinquish. Our digital footprint re-routes the city, traversing us into what Young calls ‘human machines of the algorithm’. His narrative positions human beings as ‘machines of post-human production’ within what he names a ‘DELTA City’. As an envisioned dystopia which creates perversions between the past, present and future, Hello City! is reminiscent of Kurt Vonnegut’s post-modern narrative in Cat’s Cradle. San Lorenzo, the setting for Vonnegut’s book, is on the brink of an apocalypse – the people’s only conjectural saviour would be their deluded but devoted faith to ‘Bokononism’, a superficial religion created to make life bearable for the island’s ill-fated inhabitants. Moreover, the substance ‘Ice-9’, a technological advancement, is exploited far from its original purpose of military use, leading to looming disaster. Both Bokononism and the existence of Ice-9 resonate Young’s narrative as they explore the submissive loss of free will and the consequences of allowing the future to be dictated by uncontainable entities. In Hello City! the metropolis becomes despotic and even more complex as it is designed by algorithms feeding on information instead of the endurances and sensitivities of the human body.

Like software constructed by networks, the future landscape will be a convoluted labyrinth for physical beings. Motion within the city will be ordained by a form of digital dérive structured by self-regulated and sovereign systems. Young’s video navigates us through blueprint structures simulating the connections within networks thus proclaiming the voyage as unbridled by our own corporal bodies. The body is no longer dominant. He introduces us to Lena, the world’s first facial recognition image, originally a cover from a 1972 Playboy magazine. Furthermore, he makes references to Internet sensation Hatsune Miku as a ‘digital ghost in the smart city’ whilst the three screens project and repeat the phrase ‘to keep everybody smiling’ ten times. We may speculate that for Young, the smart city has the potential to function like Alpha 60, a sentient computer system in Godard’s film Alphaville, controlling emotions, desires and actions of the inhabitants in the ‘Outlands’. As Young dictates ‘the City, looks down on the Earth’ – it becomes a geological tool and engages the speculative architect to remain relevant within the ever-changing landscape of that space.

In a preceding interview, Young refers to the speculative architect as a ‘curator’, ‘editor’ and ‘urban strategist’ attempting to decentralise power structures from conventional and conformist architectural thought. In 2014, Young’s think tank ‘Tomorrow’s Thoughts Today’ envisaged and undertook a project titled New City. New City is a series of photorealistic animated shorts featuring the cities of tomorrow; one is The City in the Sea, another is Keeping Up Appearances and the last is Edgelands. Too often, these works are projected and interpreted with the foreseeable frowning of rising consumerism concurrent with the dissolute development of technological super structures. Without a doubt, the supposition that technology is alienating us from our identities as citizens of a city is undeniable and exhaustively linked to the creation of super consumers and social media. Nonetheless, New Cities is more than just about that – comparable to the architectural intrusions of SUPERSTUDIO, the narrative of Cat’s Cradle and Alphaville,New City underlines the impending subsequent loss of human liberty with the advent emergence of the smart city whilst Hello City! injects the audience in within it.

Young’s notion of the smart city is consolidated within a Post-Anthropocene existence. Without any dispute, our world will inevitably divulge a post-anthropocene reality, but until that critical moment arrives, acts of speculation, such as speculative architecture, only exist within the hypothesis of potentiality. In fact, throughout Hello City! speculation cannot be positioned as either a positive or negative entity – it appears to lie within a neutral area of hybridity and experimentation. The narrative of Hello City! is purely speculative and thus exceedingly experimental. Like much of SUPERSTUDIO’s existence, antithetical notions of egalitarianism and cynicism run throughout Hello City! triggering perpetual seclusion of the audience’s contemplations. Conflicting positions reveal an ambivalence resulting to escalated concerns towards the act of execution. Speculative architecture itself is a purely narrative process designed on a fictitious future that is not formulated and so the eternal battle between theory and practice will always occur. Uncertainties raise an issue of pragmatism and whether speculation, evidently in architecture, is commendable. Seeing as speculation for the future is, in its most basic form, an act of research, it is regarded as the most pragmatic practise when taking into consideration any future endeavours. As the performance draws to an end, Young declares that ‘In the future everything will be smart, connected and made all better’ and then indicates towards the contradicting existence of Detroit subcultures that the future map will be unable to locate. A message loaded with properties that are paradoxical and thus ambiguous in their intent, Hello City! occupies itself with inner contradictions that only create the possibility for plural futures, a functional commons for the infrastructure of tomorrow.

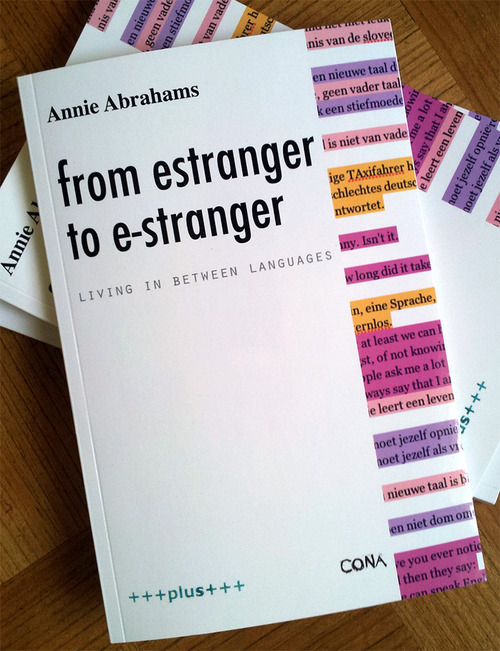

Gretta Louw reviews Abrahams’ book from estranger to e-stranger: Living in between languages, and finds that not only does it demonstrate a brilliant history in performance art, but, it is also a sharp and poetic critique about language and everyday culture.

Annie Abrahams is a widely acknowledged pioneer of the networked performance genre. Landmark telematic works like One the Puppet of the Other (2007), performed with Nicolas Frespech and screened live at the Centre Pompidou in Paris, or her online performance series Angry Women have solidified her position as one of the most innovative net performance artists, who looks not just at the technology itself but digs deeper to discover the ways in which it impacts human behaviour and communication. Even in the present moment, when online performativity is gaining considerable traction (consider the buzz around Amalia Ulman’s recent Instagram project, for example), Abrahams’ work feels rather unique. The strategy is one of contradiction; an intimacy or emotionality of concept and content, juxtaposed against – or, more accurately, mediated through – the technical, the digital, the screen and the network to which it is a portal. Her recent work, however, is shifting towards a more direct interpersonal and internal investigation that is to a great extent nevertheless formed by the forces of digitalisation and cultural globalisation.

(E)stranger is the title that Abrahams gave to her research project at CONA in Ljubljana, Slovenia, and which led to the subsequent exhibition, Mie Lahkoo Pomagate? (can you help me?) at Axioma. The project is an examination of the shaky, uncertain terrain of being a foreigner in a new land; the unknowingness and helplessness, when one doesn’t speak the language well or at all. Abrahams approaches this topic from an autobiographical perspective, relating this experiment – a residency about language and foreignness in Slovenia. A country with which she was not familiar and a language that she does not speak – regressing with her childhood and young adulthood experiences of suddenly being, linguistically speaking, a fish out of water. This experience took her back to when she went to high school and realised with a shock that, she spoke a dialect but not the standard Dutch of her classmates, and then this situation arose again later when she moved to France and had to learn French as a young adult.

There are emotional and psychological aspects here that are significant and poignant – and ‘extremely’ often overlooked. The way one speaks and articulates oneself is so often equated with intelligence and authority – and thus the foreigner, the newcomer, the language student, is immediately at a disadvantage in the social hierarchy and power distribution. Then, there are the emotional aspects and characteristics requisite for learning a language; one must be willing to make oneself vulnerable, to make mistakes. This is a drain on energy, strength, and confidence that is rarely if ever acknowledged in the current discourse around the EU, migration, asylum seekers, and – that dangerous word – assimilation. Abrahams lays her own experiences, struggles, and frustrations bare in a completely matter-of-fact way, prompting a re-thinking of these commonly held perceptions and exploring the ways that language pervade seemingly all aspects of thought, self, and relationships.

Of course this theme is all the more acute in a world that is increasingly dominated by if not the actual reality of a complete, coherent, and functioning network, then at least the illusion of one. In a world where, supposedly, we can all communicate with one another, there is increasing pressure to do so. Being connected, being ‘influential’ online, representing and presenting oneself online, branding, image – these are factors that are becoming virtues in and of themselves. Silicon Valley moguls like Mark Zuckerberg have spent the last five or six years carefully constructing a language in which online sharing, openness, and connectivity are aligned explicitly with morality. Just one of the many highly problematic issues that this rhetoric tries to disguise is the inherent imperialism of the entire mainstream web 2.0 movement.

Abrahams’ book from estranger to e-stranger: Living in between languages is the analogue pendant to the blog, e-stranger.tumblr.com, that she began working on as a way to gather and present her research, thoughts, and documentation from performances and experiments during her residency at CONA in April 2014 and beyond. Her musings on, for instance, the effect dubbing films and tv programs from English into the local language, or simply screening the English original – how this seems to impact the population’s general fluency in English – raise significant questions about the globalisation of culture. And the internet is arguably even more influential than tv and cinema were/are because of the way it pervades every aspect of contemporary life.

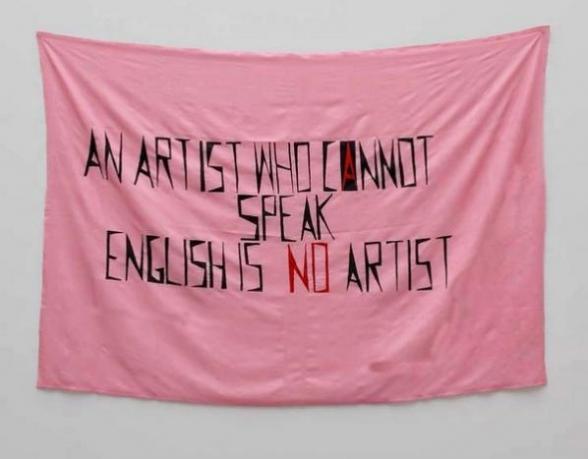

This leads one irrevocably to consider the digital colonialism of today’s internet; the overwhelming dominance of western, northern, mainstream, urban, and mostly english-speaking people/systems/cultural and power structures. [1] Abrahams highlights the way that this bleeds into other areas of work, society, and cultural production, for example, through her citation of Mladen Stilinovic’s piece An Artist Who Cannot Speak English is No Artist (1994). In a recent blog post, Abrahams further reveals the systematic inequity of linguistic imperialism and (usually English speakers’) monolingualism, when she delves into the language politics of the EU and its diplomacy and parliament [http://e-stranger.tumblr.com/post/139842799561/europe-language-politics-policy].

from estranger to e-stranger is an almost dadaist, associative, yet powerful interrogation of the accepted wisdoms, the supposed logic of language, and the power structures that it is routinely co-opted into enforcing. It is a consciously political act that Abrahams publishes her sometimes scattered text snippets – at turns associative or dissociative – in a wild mix of languages, still mostly English, but unfiltered, unedited, imperfect. A rebellion against the lengths to which non-native speakers are expected to go to disguise their linguistic idiosyncrasies (lest these imperfections be perceived as the result of imperfect thinking, logic, intelligence). And yet there is an ambivalence in Abrahams’ intimations about the internet that reflect the true complexity of this cultural and technological phenomena of digitalisation. Reading the book, one feels a keen criticism that is justifiably being levelled at the utopian web 2.0 rhetoric of democratisation, connection etc, but there are also moments of, perhaps, idealism, as when Abrahams asks “Is the internet my mother of tongues? a place where we are all nomads, where being a stranger to the other is the status quo.”

Abrahams’ project is timely, especially now that we are all (supposedly) living in an infinitely connected, post-cultural/post-national, online society, we are literally “living between languages”. The book is an excellent resource, because it is not a coherent, textual presentation of a thesis; of one way of thinking. It is, like the true face of the internet, a collection, a sample, of various thoughts, opinions, ideas, and examples from the past. One can read from estranger to e-stranger cover to cover, but even better is to dip in and out, and or to follow the links and different pages present, and be diverted to read another text that is mentioned, to return, to have an inspiration of one’s own and to follow that. But to keep coming back. There is more than enough food for thought here to sustain repeated readings.

Featured image: Nishant Shah, Roy Klabin, Francesco Warbear Macarone Palmieri, PG Macioti and Liad Kantorowicz

Finally I had the pleasure to attend to a session of the Disruption Network Lab. Physically, let’s say. Even though this was the first time I’ve managed to be in Berlin for one of its events, I’ve been a compulsory virtual follower, watching the videos of their fully recorded sessions. This is a hint for anyone who would like to watch all the previous keynotes and talks.

With its first edition in April, Disruption Network Lab is an ongoing platform of events and research on art, hacktivism and disruption, held at Studio 1 of Kunstquartier Bethanien, in partnership with Kunstraum Kreuzberg/Bethanien, in Berlin. On 31st of October it has held its 5th session, PORNTUBES: Sharing the Explicit. Aiming to discuss the role of porntubes in the sex and porn industry it gathered porn practitioners, entrepreneurs, sex work activists and researchers, to engage in a debate on the intertwining of porn with the Internet.

Pornography has always been a pioneer in using new technologies for its distribution and promotion. Internet, by allowing anonymous access to porn from the comfort of everyone’s home it seemed to be the ultimate tool for the porn industry’s expansion, to say the least. As pointed by Roy Klabin during the talk, 38,5% of the time we spend on the Internet is spent watching porn. As in many other spheres, it also seemed to be the beginning of a new era of labour liberation with an apparent decentralisation from the big porn production houses. This has allowed the blossoming of new small and independent companies with their own place in the market. But if cyberspace once seemed to offer a possibility to escape the tentacular control and exploitation exercised by the corporative monopolies, it is now known that the rebellion of the cybernetic innovators – creators of porntubes and new online sex tools – seems to be purely a coup d’etat.

The opening keynote was by Carmen Rivera, a Mistress and Fetish-SM-performer, with a long history in the porn industry business, with an experience of the migration of porn from cinema to VHS and later to the Internet and then onto the porntubes. In conversation with Gaia Novati, a net activist and indie porn researcher, Carmen tells us her personal and professional story and immediately gives a better understanding on how porntubes – such as Redtube, X-Hamster or Youporn – have an ambiguous influence in the porn industry. Once perceived as a democratic tool allowing small porn producers to expand their radius of audience-reach, Rivera explains how much of a perverse tool of exploitation it has become and one that small producers have become too dependent on.

The fast pace of the Internet creates a lot of pressure to satisfy the hunger of porn consumers. As has become virtually infinite “fast-porn” is closely aligned with the capitalist paradigm of production, putting a bigger focus on quantity rather than quality. As the Internet leaves no space for durability — one day you’re in, the next day you’re out — careers become frail, the work of these companies are highly precarious and the concept of the “porn-star” is a short lived mirage.

Rivera also highlights how online piracy has become virtually unavoidable resulting in gigantic losses to the porn industry. As producers see their films ending up on porntubes free of access, lawsuits don’t come as a viable solution but as financial black holes for any small or even medium companies. Even though the future doesn’t seem bright, Rivera doesn’t quit. Her battle cry: we need to create a bigger awareness of the pestilent system that controls the online porn industry. New tools of disruption need to be found to fight against these new power asymmetries established through the domination of cybernetic capital.

After the keynote, the discussion shifted to examining new tools of online sex work such as the project PiggyBankGirls, self-proclaimed as the first erotic crowdfunding for girls. Unfortunately, Sascha Schoonen, CEO of the project, wasn’t able to attend. Instead a short promo video was presented introducing the project, giving some tongue-in-cheek examples on how girls could profit from this crowdsourcing tool.

Women upload videos pitching their ideas or projects – financing a shelter for stray animals, the payment of tuition fees, a trip to Japan, – and then share online porn performances in exchange for support from “occasional sugar daddies”. Although one wonders if this isn’t just a euphemism – a sanitised version, let’s say – of already existing tools used by women who need money, regardless of them making public how they intend to spend money Nevertheless, it is true that the actual exploitative system needs to be dismantled, workers should be getting a bigger share for their labour and PiggyBankGirls poses as one more tool to do so, however this project also left many unanswered questions. Who are actually the women who can profit out of it? PiggyBankGirls promo tries to make this form of sex labour sound “cute”, easy and accessible. However, is just another tool for established porn actresses to diversify their means of income?

The panel, moderated by Francesco Warbear Macarone Palmieri, socio-antrophologist and geographer of sexualities, included abstracts showing a wide array of perspectives on the issue of porntubes and online sex work. The researcher Nishant Shah opened the panel with a wonderful talk ranging from porn consumerism to porn politics and how porn is influencing our digital identities. In a porn-consuming society, from establishing clear distinctions between “love” and “porn”, respectively meaningful and perverse, desirable and visceral desire, porn seems to be contingent on the morals of the spectator – as it only exists through the spectator it has also become a tool of puritan regulation. From Facebook teams of censorship and sanitisation of the virtual space to websites such as isitporn.com it is possible to understand that the concept of porn becomes itself a regulator of our sexual expressions, defining the line that separates decency from indecency. Paving the way to the pathologization of porn practices but yet dictating the meaning of authentic sexual performances, as the only visceral forms of sexual performances available, Shah pointed out how pornography, as a cultural and digital artefact, works in the regulation of our societies and in the production of our identities. Giving the example of Amanda Todd, who committed suicide after suffering from bullying for exposing her sexual body online, Shah shows how new forms of “porn” take place in the digital, from doxxing to unintended porn being perceived as such, enabling new forms of violence – let’s say porn-shaming.

Also focusing on porn consumerism, Roy Klabin, investigative documentarist/filmmaker, goes back to the discussion initiated with Carmen Rivera on porntubes VS porn producers and how producers make money. According to Roy, MindGeek, the company that owns most of the porntubes – from Youporn to Redtube – has been one of the main entities responsible of the destruction of the porn industry. By creating piracy websites holding gigantic libraries of free access to porn and making revenue out of the advertisement, resulting in huge losses for the porn companies which at the same time had become dependent on the tubes to advertise their work. Roy makes an appeal to porn producers to diversify their strategies: from webcams to virtual reality, the porn industry needs to be one step ahead of the contemporary systems of digital exploitation.

PG Macioti, a researcher and sex workers rights advocate and activist, together with Liad Kantorowicz, performer and sex workers’ activist, presented an overview on how the Internet has reshaped sex work – from sustainability to work conditions – listing some of the outcomes, pros and cons, of the extension of sex work to the virtual spaces. Online sex work, namely erotic webcam work, has enabled a proliferation of sex work by offering safe, independent and anonymous services. On the other hand with the insertion of sex work on the capitalist mode of production, just like in many other forms of digital labour it has rendered a bigger alienation to the workers – who work mainly alone and, also due to stigma, don’t share any contact with fellow colleagues – resulting in a more and more precarious labour, with sex workers being paid by minute, having to pay for their own means of production and usually paying a big share of their income to the middleman webcam services host agency.

Overall, the Internet has enabled a multiplication of narratives on sex work but the power asymmetries between the online corporations and workers results in a growing exploitation and precariousness. The transversal message to all participants seems to urge for disruptive tools for online sex work, tools of self-empowerment and emancipation within the digital paradigm. Quoting the Xenofeminism manifesto by Laboria Cubonics, “the real emancipatory potential of technology remains unrealised” and the Disruption Network Lab might be the much needed spark for this revolution.

The PORNTUBES event couldn’t have had a better ending with a party held in the legendary KitKatClubnacht, a sex & techno club that is open since 1994, famous for both its music selection and its sexually uninhibited parties. It seems an exciting idea, to say the least, to bring all together researchers, porn entrepreneurs and activists to this incredible venue after an intense afternoon discussing the porntubes.

Concluding the series of conference events of Disruption Network Labs during 2015, the next event will be STUNTS: Distributed, Playful and Disrupted, taking place on the 12th of December, at the Studio 1 of Kunstquartier Bethanien, and the direct link is: http://www.disruptionlab.org/stunts/. This time the discussion will focus on political stunts as an imaginative and artistic practice, combining hacking and disruption in order to generate criticism of the status quo. As the immense dragnet of state-surveillance extends it becomes imperative to understand which are the available tools of obfuscation, how it is (still) possible to hack the system and which tools of political resistance can be deployed Disruption Network Lab wraps the year with a tempting offer, inviting artists, hackers, mythmakers, hoaxers, critical thinkers and disrupters to present practices of mixing the codes, creating disturbance, subliminal interventions, giving raise to paradoxes, fakes and pranks.

The new project by Guido Segni is so monumental in scope and so multitudinous in its implications that it can be a bit slippery to get a handle on it in a meaningful way. A quiet desert failure is one of those ideas that is deceptively simple on the surface but look closer and you quickly find yourself falling down a rabbit-hole of tangential thoughts, references, and connections. Segni summarises the project as an “ongoing algorithmic performance” in which a custom bot programmed by the artist “traverses the datascape of Google Maps in order to fill a Tumblr blog and its datacenters with a remapped representation of the whole Sahara Desert, one post at a time, every 30 minutes.”1

Opening the Tumblr page that forms the core component of A quiet desert failure it is hard not to get lost in the visual romanticism of it. The page is a patchwork of soft beiges, mauves, creams, and threads of pale terracotta that look like arteries or bronchia. At least this morning it was. Since the bot posts every 30 minutes around the clock, the page on other days is dominated by yellows, reds, myriad grey tones. Every now and then the eye is captured by tiny remnants of human intervention; something that looks like a road, or a small settlement; a lone, white building being bleached by the sun. The distance of the satellite, and thus our vicarious view, from the actual terrain (not to mention the climate, people, politics, and more) renders everything safely, sensuously fuzzy; in a word, beautiful. Perhaps dangerously so.

As is the nature of social media platforms that prescribe and mediate our experience of the content we access through them, actually following the A quiet desert failure Tumblr account and encountering each post individually through the template of the Tumblr dashboard provides a totally different layer to the work. On the one hand this mode allows the occasional stunningly perfect compositions to come to the fore – see image below – some of these individual ‘frames’ feel almost too perfect to have been lifted at random by an aesthetically indifferent bot. Of course with the sheer scope of visual information being scoured, packaged, and disseminated here there are bound to be some that hit the aesthetic jackpot. Viewed individually, some of these gorgeous images feel like the next generation of automated-process artworks – a link to the automatic drawing machines of, say, Jean Tinguely. Although one could also construct a lineage back to Duchamp’s readymades.

Segni encourages us to invest our aesthetic sensibility in the work. On his personal website, the artist has installed on his homepage a version of A quiet desert failure that features a series of animated digital scribbles overlaid over a screenshot of the desert images the bot trawls for. Then there is the page which combines floating, overlapping, translucent Google Maps captures with an eery, alternately bass-heavy then shrill, atmospheric soundtrack by Fabio Angeli and Lorenzo Del Grande. The attention to detail is noteworthy here; from the automatically transforming URL in the browser bar to the hat tip to themes around “big data” in the real time updating of the number of bytes of data that have been dispersed through the project, Segni pushes the limits of the digital medium, bending and subverting the standardised platforms at every turn.

But this is not art about an aesthetic. A quiet desert failure did begin after the term New Aesthetic came to prominence in 2012, and the visual components of the work do – at least superficially – fit into that genre, or ideology. Thankfully, however, this project goes much further than just reflecting on the aesthetic influence of “modern network culture”2 and rehashing the problematically anthropocentric humanism of questions about the way machines ‘see’. Segni’s monumental work takes us to the heart of some of the most critical issues facing our increasingly networked society and the cultural impact of digitalisation.

The Sahara Desert is the largest non-polar desert in the world covering nearly 5000 km across northern Africa from the Atlantic ocean in the west to the Red Sea in the east, and ranging from the Mediterranean Sea in the north almost 2000 km south towards central Africa. The notoriously inhospitable climate conditions combine with political unrest, poverty, and post-colonial power struggles across the dozen or so countries across the Sahara Desert to make it surely one of the most difficult areas for foreigners to traverse. And yet, through the ‘wonders’ of network technologies, global internet corporations, server farms, and satellites, we can have a level of access to even the most problematic, war-torn, and infrastructure-poor parts of the planet that would have been unimaginable just a few decades ago.

A quiet desert failure, through the sheer scope of the piece, which will take – at a rate of one image posted every 30 minutes – 50 years to complete, draws attention to the vast amounts of data that are being created and stored through networked technologies. From there, it’s only a short step to wondering about the amount of material, infrastructure, and machinery required to maintain – and, indeed, expand – such data hoarding. Earlier this month a collaboration between private companies, NASA, and the International Space Station was announced that plans to launch around 150 new satellites into space in order to provide daily updating global earth images from space3. The California-based company leading the project, Planet Labs, forecasts uses as varied as farmers tracking crops to international aid agencies planning emergency responses after natural disasters. While it is encouraging that Planet Labs publishes a code of ethics4 on their website laying out their concerns regarding privacy, space debris, and sustainability, there is precious little detail available and governments are, it seems, hopelessly out of date in terms of regulating, monitoring, or otherwise ensuring that private organisations with such enormous access to potentially sensitive information are acting in a manner that is in the public interest.

The choice of the Sahara Desert is significant. The artist, in fact, calls an understanding of the reasons behind this choice “key to interpret[ing] the work”. Desertification – the process by which an area becomes a desert – involves the rapid depletion of plant life and soil erosion, usually caused by a combination of drought and overexploitation of vegetation by humans.5 A quiet desert failure suggests “a kind of desertification taking place in a Tumblr archive and [across] the Internet.”6 For Segni, Tumblr, more even than Instagram or any of the other digitally fenced user generated content reichs colonising whatever is left of the ‘free internet’, is symbolic of the danger facing today’s Internet – “with it’s tons of posts, images, and video shared across its highways and doomed to oblivion. Remember Geocities?”7

From this point of view, the project takes on a rather melancholic aspect. A half-decade-long, stately and beautiful funeral march. An achingly slow last salute to a state of the internet that doesn’t yet know it is walking dead; that goes for the technology, the posts that will be lost, the interior lives of teenagers, artists, nerds, people who would claim that “my Tumblr is what the inside of my head looks like”8 – a whole social structure backed by a particular digital architecture, power structure, and socio-political agenda.