Featured image: ToolsForAction.net / Artúr van Balen and QueerSport.info / Zeljko Blace, ‘POP-UP RAINBOW’, 2014

Zeljko Blace is working in(-between) contemporary culture, media technologies and sport, cross-pollinating queer, media and social activism. He is one of the initiators and a co-curator of the project ‘contesting/contexting SPORT 2016.’

to reclaim the field with art and activism

exhibition and program in Berlin (08.07-28.08.2016)

at nGBK and KunstraumKreuzberg/Bethanien

http://ccSPORT.nGbK.de

www.facebook.com/cc.sport.2016/

www.twitter.com/CcSPORT2016

The exhibition and program contests the field of SPORT through critical art and activist practices. Coming from feminist and queer practices, the project aims to challenge discrimination and encourage emancipation. SPORT is contextualized from its declarative neutrality and autonomy, rendering diverse influences, but also experiences and conditions of SPORT realities visible.

Organized by the ccSPORT international working group of the nGbK including also: Caitlin D. Fisher, Carmen Grimm, Mikel Aristegui, Sarah Bornhost, Stuart Meyers, Imtiaz Ashraf, Andreea Carnu, with support from: Tom Weller, Alexa Vachon, Ilaa Tietz, Tabea Huth, Barbara Gruhl, Steffy Narancic, Tristan Deschamps, Coral Short, Gegen Berlin, Schwules Museum, and advisors: Alex Brahim, Jennifer Doyle, Philippe Liotard, Jules Boykoff, Stephane Bauer and †Frank Wagner.

BOSMA: The ‘contesting/contexting SPORT 2016’ exhibition and program shows a wide range of uncommon perspectives on sports, questioning cultural systems embedded in them we hardly ever think about. Why did you make this exhibition?

BLACE: In this ‘networked’ and globalized time we paradoxically live out a multiplicity of highly fragmented realities, niched in specialized interest groups, while ‘others’ feel they can not contribute or even relate to them. It felt like this to me in my work during the late/post 90s with tactical and net media activism/art – fully disconnected from queer politics and sports organizing for which I had an increasing interest. In general the field of sport has not been part of the lives of many intellectuals, activists and creatives. Many had bad (even traumatic) experiences with sport in childhood and adolescence, feeling alienated, or simply not recognizing it as a possible field to develop work in (unlike right-wing populists in tribal fan cultures). Simply put, the sport system has been taken for granted in its current form. Hence, my first curated sport exhibition title, paraphrased ‘sport hater’ Chomsky, in ‘Another SPORT is possible?!.’ (2012, Galerija NOVA, Zagreb, Croatia). My Berlin colleagues and ccSPORT co-founders Caitlin Fisher, Tom Weller and Carmen Grimm felt the same about the separation of sport from arts, activism and academic research. Together (with the support of exhibition spaces nGbK and Kunstraum Kreuzberg/Bethanien) we made plans to instigate and support intersections, cross-pollinate practices and perspectives between these fields through an exhibition, program and media work. We strongly felt the field of sport would never become self-critical and reform, nor would it engage with a wider audience beyond a given consumerist mode, if left to the managerial mentalities and the opportunism of its leaders. We need to reclaim the field of sport together to change it.

Is this the first ever exhibition criticizing the cultural and political dimensions of sports, and if not, how does your perspective relate or differ from earlier approaches?

I can not say with complete certainty what other group exhibitions on sport critique have taken place before. There have been many on a small scale, marginal in comparison to the huge exhibitions that ‘celebrate’ sports and are used as decor and entertainment accompanying sport spectacles (a notable exception is the seminal work ‘Electronic Café’ by K. Galloway & S. Rabinowitz at the 1984 LA Olympics, that actually provides space for interaction/discussion in between different city locations). There were also a few archival exhibitions looking at historical artifacts and documentation critically, as well as some that were experimental and playful (such as the Fluxus Olympiad, scripted as non-competitive multi-sports event) but these approaches were somewhat one-sided. We aspire to create a basis for both critical reflection and informed envisioning of possible developments, by looking at personal perspectives and artistic visions, next to grass-root alternatives and interventions.

The main threads in the exhibition seem to be gender, queerness and the connection between culture, commerce and rules in sport. Are these the main issues at hand?

Indeed our starting points were feminist and queer positions, but we were also very interested in the wider range of intersections and systemic issues within the field of sport that we could connect, rather than focusing on single-issues like homophobia or racism as is often done in mainstream sport campaigns. We decided very early on that the project would not be about identity politics, but rather about the multiplicities of axes of discrimination. There is a spectrum of emancipation efforts and practices that inspire us to think outside of gender norms, result-focused competitions, spectacle creating events and omnipresent ‘development’ narratives – which ignore for example that women had more access to certain sports historically in different geographies then they did in past 30 years of globalized neoliberalism.

augmented_profile from Diego Grandry on Vimeo..

How do you see the role of the media in the perception of sport?

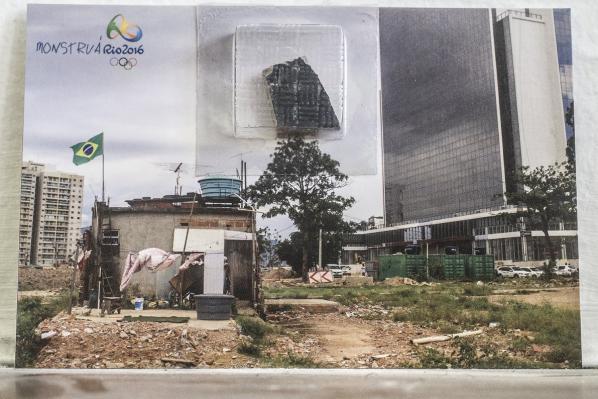

Traditional broadcast media are the key stakeholder in the Olympics and similar sporting-spectacles. They have made the organizers of large sport events addicted to their huge broadcast contract revenues, but then inherently push for the spectacle of mega-events even further at the cost of other aspects. Newer sports that have evolved around this economy of attention have often sexed athletes (most visible with female beach volleyball) or at least contributed to enforcing gender stereotyping (like the feminization of soccer/football to the point that there are almost no short haired players at the Olympics). Instead of actively evolving with the progressive trends in sport, most broadcasters deepen the stereotypes; too often commenting on the marital status and appearance of female athletes, or referring to them as girls. Athletes from smaller countries, and sports that receive the least coverage are often looked down on, projecting neo-colonial relations on them (or hosts as in Brazil).

With internet networks and ‘social’ media the situation it is more complex as the interactive nature of media often allows for feedback and multiple standpoints in the same, or various foras. These media diversity brings to the surface and exposes critical minority voices and individuals who are able to argue against norms and question their necessities. For example, the tokenizing of muslim female athletes during these last Olympics received great reactions including historical facts about muslim women winning medals in the ‘80s and ‘90s. Also the outing of gay athletes by one reporter, was widely criticized online and the media hype reboot around Caster Semenya was compensated by internet and hybrid media (i.e. AJ+) publishing numerous expert articles and even giving voice to many (including former opponents critics converted to supporters as in case of Australian runner Madeleine Pape).

The connection between rules and cultural systems in sports is fascinating to me. You have worked as an organizer/curator in Multimedia Institute/MaMa before focusing on sport. What is your perspective on the rise of technological systems in the enforcement of rules, like for example drug testing or electronic goal-line and court line tracking?

Actually, the technological aspects of sport are the ones that still need to be addressed more specifically (technology centered single sport competitions exist since years, with The Cybathlon as their olympics premiere in Zurich, October 8th 2016). They not only re-enforce certain types of (measurable) norms, but also reduce the complexity into what appears to be arguable ‘logic’ and ‘common sense,’ while hiding other aspects (psychological and even aesthetic). Drug testing is an important measure of control, but is usually focused on the supra-performance of medal-winning athletes, rather than concerning itself with more generally applicable questions: what are the drugs, who has access to them and why. As long as the prevalent ‘production’ of results at all costs is dominating sports, the goal of ‘clean’ sports regardless of technological advancements in control will remain impossible. Gender policing at the Olympics has had a lengthy technological path, starting with visual and medical inspections, moving on to DNA and hormone testing and nowadays being fully questioned. Measuring and tracking technologies have the most interesting potential, not only for confirming line calls but for reshaping sports into allowing potentialities of variable norms and measuring based on generative fields/infrastructures. However, this kind of innovation is more likely to develop in the edges of eSports industry (that is pushed by novelty rather than burdened by traditions and conventions) and then maybe get normalized into traditional sport competitions once existing sport federations and regulatory bodies start losing young markets.

It was important for us to initiate conversations and collaborations that were not in place before, especially between those excluded from the mainstream sport system. We stirred up some interest from academic researchers for immediate follow-ups, but also informed some activists and artists of each other’s work. Ideally this could be developed further to elevate the critical and creative work in the field of sport and address issues in multifaceted ways.

We hope the exhibition and program enabled visitors to develop a more articulate position rather than just LOVING / HATING SPORTS, maybe supporting our platform — and ideally also inspired them to build personal or collective proactive relationships to sports. Maybe through practices of engagement against mega-spectacles and hyper-commercialization of sports, while supporting/partaking in grass-root sports or reforming the mainstream system.

Now we look forward to have the time for reflection after the intense work of materializing the exhibition and the extensive events program, as well as to see what future sport events could be interesting to contest and/or contextualize. One of the most important follow-ups is establishing an online space for sustainable communication, exchange and sharing information, know-how, methods, most likely using wikis, maps and media that came out of our research and workshops during the summer exhibition program.

This will be ncluding video of closing lecture by prof. Jennifer Doyle on art, sports and questioning the origins and need for the gender segregation in sports! More info will be appearing on our working website http://www.ccSPORT.link/

Featured image: Artist Suguru Goto discusses his work.

London 2012: there is of course one event which springs to mind when we think about this city and the year we’re in, but there is also another significant event happening in London right now, one which is very important for the digital and media arts world. It is the year that Watermans Arts Centre is holding the International Festival of Digital Art 2012.

As well as showcasing an array of digital art by internationally renowned artists, the programme also offers the opportunity for members of the public to get involved in discussions around themes that the Festival touches on through the seminar series accompanying the shows. These are in collaboration with Goldsmiths, University of London. Nearly three months in, the Festival has launched two exciting shows,Cymatics by Suguru Goto and UNITY by One-Room Shack Collective.

The first show, Cymatics, is a kinetic sound and sculpture installation that expresses Goto’s vision of nature. To enter it, the audience step through a door into a boxed, dark room within which they are presented with a touch screen interface, a shallow metal tank holding water and a screen showing a video feed of the water in the tank. The piece invites the audience to move the water in the tank by manipulating sound waves via an interactive screen. The result of the interaction is a stunning variety of geometric shapes, demonstrating the distortion that sound waves can have on a substance. This occurrence reveals the bridge between technology and nature, which fits into Goto’s re-occurring theme within his work of the relationship between man and machine.

The seminar which coincided with the show, Interactivity and Audience Engagement, was chaired by Régine Debatty and featured on the panel Tine Bech, Graeme Crowley and Tom Keene, all who which explore audience engagement in different ways within their work. Tine Bech is a visual artist and researcher whose installations invite audiences to engage in playful interactions, from chasing a motion reactive spotlight in Catch Me Nowto sound triggering shoes in Mememe. Tom Keene is an artist technologist whose focus intersects participation, communication and technology. His work is multidisciplinary, investigating the way we communicate, mediated by technology. His practice is diverse, from exploring the potential relationships between networked everyday objects in Aristotles Office to inviting a community to comment on their local issues through signs in Sign X Here. Graeme Crowley is a designer and artist who has created installations for prominent public areas, including The Wall of Light, commissioned by Arrowcroft Plc for the centre of Coventry and Spiral/Bloom commissioned for a hospital in Rochford by the NHS.

I found the juxtaposition of these three practitioners very interesting as each of them explore the interaction between audience and technology in varying ways. Bech’s work is very tactile and sculptural, almost making people forget the technology behind it. She likes to look at technology as something we can mould and which can be used to explore the wider issues which art can bring up, rather than just focussing on the tech itself and how ‘shiny’ (to use her own term) it is. In contrast to this, within Keene’s practice technology feels very prominent, visually as well as conceptually. Crowley’s focus is different again as it mostly operates within the commercial sphere. It therefore is produced for greater public consumption and needs to withstand being a permanent exhibit, becoming part of the architecture it is planted on rather than something which is temporary. The talks given by each panel member and discussions which accompanied them were all diverse and brought up interesting points around the idea of audience engagement and interactivity. Members of the audience entered into these discussions with ease, creating an open dialogue which itself was participatory and engaging.

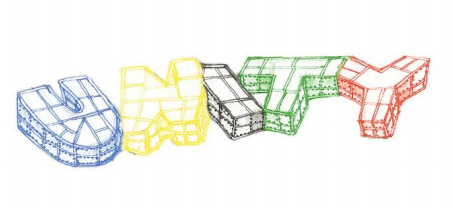

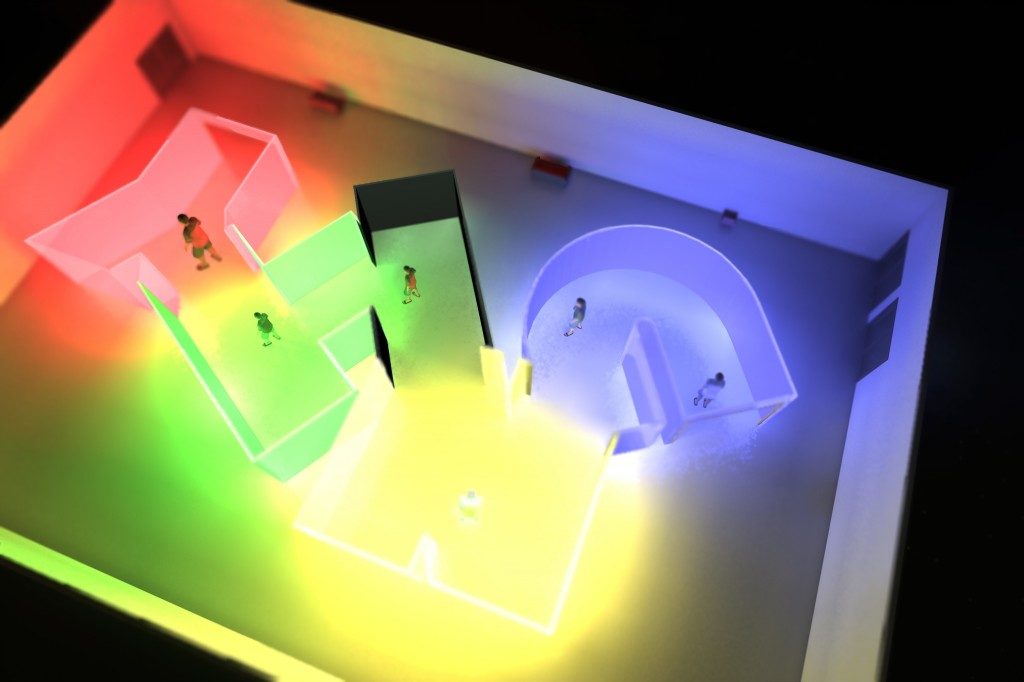

UNITY, by One Room Shack is the current exhibit as part of the International Festival of Digital Art 2012, bringing a piece of work to the gallery which aims to embody the Olympic spirit, visually as well as conceptually.

Design for Unity

The installation takes the form of a transparent maze, angular in its structure and illuminated with different coloured LED lights in each section. Each illuminated section of the structure forms a different letter, all together spelling the word ‘unity’. As the audience navigate their way through the installation, their movement is picked up by motion sensors, triggering the LEDs at each point to turn on. These each represent a particular colour of the Olympic rings.

The ideologies of the Olympic Games linked with an immersive space explores the value of ‘being together’, something which the African humanist philosophy Ubuntu also speaks about.

UNITY is effective in exploring the theoretical concepts embedded within it through a playful and simple interactive structure. As an individual you step from section to section with the different groups of LEDs individually illuminating you as you go through the work. When a group of people interact with the piece at the same time however, the piece lights up as a whole, echoing the values of being together that UNITY invites us to explore. It is through enabling this experience, that the work celebrates and explores human connections.

I do find it interesting how the piece has such a strong stance towards the more idealistic ideologies of the Olympics, especially when taking into account the anti Olympics sentiment present in London. The event does bring people together, but unfortunately as we’ve seen in East London and also at previous Olympic locations across the globe, they also have the ability to put local communities at risk through rising rents and eviction [1]. UNITY looks at ‘…understanding the implication of UNITY on humanism in a neo-liberal world where hyper-capitalism and love of excess trump compassion and selflessness.’ [2] but in reality, the Olympics have unfortunately become something which arguably embody these traits. This said, I do think that UNITY is an incredibly beautiful piece in its visual execution and that its interaction compliments the theoretical idea which it is looking to address.

I look forward to the remainder of the International Festival of Digital Art 2012 and the eclectic ideas within media and digital art which the programme explores. I interviewed Irini Papadimitriou, Head of New Media Arts Development at Watermans, about the Festival:

Emilie Giles: First of all, can you tell us what the premise is behind the International Festival of Digital Art 2012?

Irini Papadimitriou: The idea behind the Festival started from a decision to develop a series of shows that could form a discussion rather than being one-off exhibitions and help engage more people in the programme. In the last year we have been focusing more in participatory and/or interactive installations so I thought it’d be interesting to dedicate this project and discussions in exploring more ideas behind media artworks that invite audience engagement as a way of understanding our work in the past year.

Since this was going to take place in 2012 we felt it would be necessary to open this up to international artists so this is how the open call for submissions came up last year. We received so many great proposals it’s been very hard to reach the final selection, but at the same time the opportunity of having a year-long festival meant we could involve as many people as possible and hear many voices not only through the exhibitions (this is just one part of the Festival) but also with other parallel events such as the discussions, presentations of work in progress by younger artists and students, the publication, a Dorkboat (coming up in June with Alan Turing celebrations), as well as collaborations with other organisations or artists’ networks and online.

EG: Touching on your last answer, the Festival has a clear aim then to engage people in discussion rather than just being viewers of a show. Do you think that within media and digital art there is a particular need for this approach?

IP: I think that hearing people’s thoughts and responses and enabling discussion is important for all exhibitions and art events but specifically for the Festival (since the aim is to question & explore audience participation). It was very relevant to hear ideas and views from other artists, technologists, practitioners etc but also audiences, rather than just the participating artists.

Also, and this is my view, I think as media and digital art use technologies that many of us are not particularly familiar with or if we use technologies it will be most probably as consumers, it’s important to talk about and discuss the process (as well as impact of technologies) both for the artists as well as for audiences.

EG: The themes chosen for the programme are diverse and each relevant to media and digital art in their own way. What are the reasons for each focus and why?

IP: The themes explored in the Festival result mainly from the selected proposals and discussions with the artists. There were so many things to talk about so having these themes was a way to start from somewhere and help understand better the installations shown throughout the year. The seminars that we are organising are an opportunity for the artists to talk about their work and share their ideas with both audiences but also with other artists invited to take part in the panels. It is also a way of discussing these themes and presenting other work that raises similar issues. The seminars are shaped around the themes such as perception and magic in digital art, sound and gesture, geographies, virtual spaces as artistic mediums and of course participation and interaction. We are currently working on a publication with Leonardo Electronic Almanac which will be coming out in the next couple of months and will include essays from artists, academics and students as well as interviews with the artists behind the selected proposals. Again the catalogue has the Festival themes as a starting point but we tried to combine different content and ways of communicating these.

EG: How do the pieces featured in the exhibition question audience engagement, participation and accessibility ?

IP: The artists presenting work are exploring participation and audience engagement in different ways and I think we will have also interesting outcomes from the seminars and the publication which will allow us to explore these ideas further.

In the current installation, UNITY, One Room Shack collective are using the playful structure of a maze (in the form of the word UNITY with each letter lighting up in the colours of the Olympic rings) inviting people to walk inside to reflect and draw upon the complex nature of human reality and ‘difficult’ aspects of human existence.

Michele Barker and Anna Munster who will be showing HokusPokus later on are interested in exploring how we perceive actively in relation to our environment, how we see, what we see and how this makes us ‘interact’. HokusPokus inspired from neuroscience examines illusionistic and performative aspects of magic to explore human perception, movement and senses. The tricks shown in HokusPokus have not been digitally manipulated; they will unfold temporally and spatially, amplifying and intensifying aspects of close-up magic such as the flourish and sleight of hand.

The Festival will close with an installation by American artist Joseph Farbrook, Strata-Caster, which was created in Second Life mirroring the physical world, exploring positions of power, ownership, identity and drawing parallels between virtual and physical worlds. An interesting and important part of the installation is the use of a wheelchair by visitors to enter and navigate Strata-Caster.

EG: How have the 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games inspired the Watermans International Festival of Digital Art?

IP: As we are trying to explore what participation is we thought it would be an interesting link (rather than inspiration) between the Festival and the Games/Cultural Olympiad since they are meant to symbolise, promote and inspire values like creativity, collaboration, participation, engagement etc. The Festival isn’t about the Olympics and participating artists didn’t have to propose work that linked to the Games, but we did receive many proposals that reflected on the Games, what they represent and the meaning of participation, so some of these proposals are being shown as part of the Festival, such as One Room Shack’s UNITY and Gail Pearce’s Going with the Flow.