Featured image: A live portrait of Tim Berners-Lee (an early warning system). Thomson and Craighead. March 2012.

Flat Earth was published to accompany two solo exhibitions. The first, Not even the sky at MEWO Kunsthalle, Memmingen, Germany from 26 October 2013 – 6 January 2014 and the second Maps DNA and Spam at Dundee Contemporary Arts, Scotland from 18 January – 16 March 2014. The book contains a foreword by Axel Lapp, essays by Dundee Fellow Sarah Cook and DCA Director Clive Gillman as well as an interview with the artists by Steve Rushton.

On the whole, the mainstream art world has failed to ‘convincingly’ adapt to (new) media art and similar contemporary art practices using networks and technology. Thomson & Craighead have overcome this impasse and this is one of a few reasons why they’re so interesting to look at as contemporary artists. The book, Flat Earth does not propose to cover all of their art and this review does not propose to cover all that it is featured in it. The review features Flat Earth Trilogy, The End, October and TRIGGER HAPPY (not in the book).

“Their work provides us with a new perception, through

a completely unexpected multi-focal perspective. They reveal

the wide ramifications of systems of information exchange and

provide us with an insight into the resulting infrastructure of

our own thinking.” [1] (Alex Lapp 2013)

TRIGGER HAPPY: Shooting The Messenger.

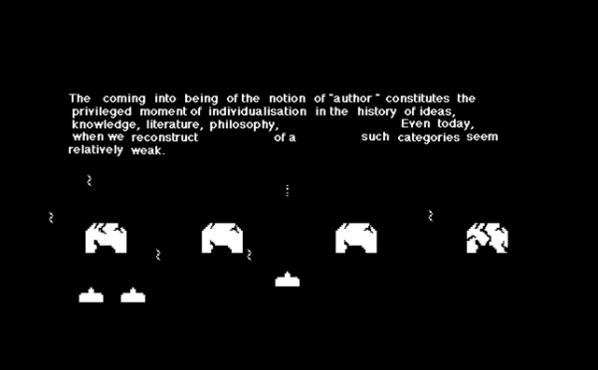

Although TRIGGER HAPPY (1998), is not featured in the publication it provides a useful introduction to some of the ideas and conceptual approaches present in Thomson & Craighead’s later artworks. I first experienced the work online, but it’s also a gallery installation that takes the form of an early shoot-em-up arcade game, Space Invaders. This work reflects the sly and cheeky side of Thomson & Craighead and tells us how humorous they can be in their art. TRIGGER HAPPY is philosophical and playful. It asks the player to shoot down the text of Michel Foucault’s essay What Is an Author? published in 1969. [2]

Foucault said the depiction of knowledge is a production and truth is produced, and it is always a reconstructed falsification. In a way TRIGGER HAPPY gives us a chance to shoot at Foucault, who in this respect is the annoying messenger. At gut-level, this art object recognises that on the whole we prefer to shoot at things or play games, than to deal with the complex and pressing questions of our time. Even if the gamer does manage to destroy Foucault’s text, this action prompts an existential enactment of doubt and induces a more vulnerable state of interpassivity. This relates to the illusion of agency when playing games, using corporate online platforms like Facebook and other experiences involving interaction with media, and it can also be extended to life situations. Slavoj Žižek proposes that interpassivity is the opposite of interaction and says “that with interactivity a false activity occurs: ‘you think you are active, while your true position, as it is embodied in the fetish, is passive’. Žižek refers to the Marxist notion of commodity-fetishism to imply that social relations are increasingly reduced to objects (Žižek, 1998).” [3]

We can almost hear the catchphrases “it’s only a movie” or “it’s only a game” as we are compelled to shoot at rather than attend to the messages that may serve to enlighten us and free us from our societal conditioning.

Flat Earth Trilogy: A networked society’s gaze at its mediated self.

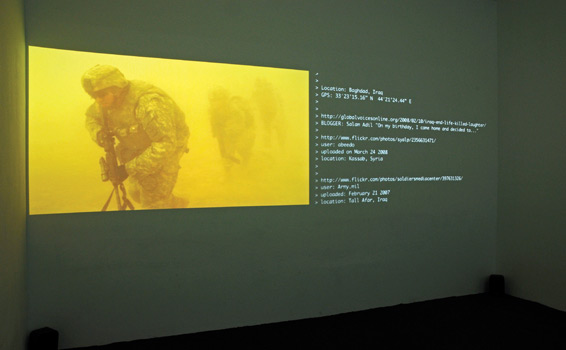

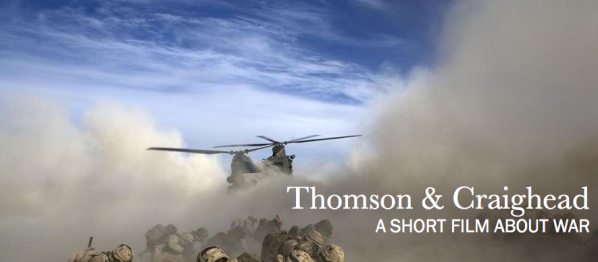

The Flat Earth Trilogy is a series of documentary artworks each made entirely from information found on the World Wide Web; with fragments collected from people’s blogs, This covers a six-year period beginning with Flat Earth (2007) A short film about War (2009/2010) and then ends with Belief (2012).

Commenting on A Short Film About War, on their website, Thomson & Craighead write “In ten minutes this two screen gallery installation takes viewers around the world to a variety of war zones as seen through the collective eyes of the online photo sharing community Flickr, and as witnessed by a variety of existing military and civilian bloggers.” [4]

In the book Flat Earth Steve Rushton discusses with Thomson & Craighead why he feels A short film about War works for him best. He says, “It seems to make a claim on truth – which is the traditional claim of the documentary in particular and photography in general – whilst at the same time it shows us that truth is constructed.” [5] (Rushton 2013)

These works challenge our notion of what a documentary is, what and who the author is, and leaves us with the question, what does this mean for the wider society? This brings us back to Foucault’s ideas on the production of truth and its falsification. Tom Snow writes “In the essayistic act of image compilation then, the piecing together of filmic clips and stills distorts the dividing line between fiction and fact, and reimagines the enigmatic relations between photographic mediums and the condition of representation.” [6] (Snow 2009)

Flat Earth, A short film about War, and Belief all relate to topics concerning human values, conflicts, militarism and everyday societal struggles. “Machines,” wrote Gilles Deleuze in his examination of Foucault’s thought, “are always social before being technical. Or, rather, there is a human technology before which exists before a material technology.” [7] (Berger 2014) And so the technologies we produce are another materialization of the continuing human story.

Millions of people, en-masse, are uploading their personal data (different indications of their states of being) to a collective assemblage. Alex Galloway says that in order to get a better understanding of what networks are we must put aside the idea that networks are a metaphor. He proposes networks as part of a materialized and materializing media. He views this as an important step toward understanding the “power relationships in control societies.” [8] (Galloway 2004)

“It is a set of technical procedures for defining, managing, modulating, and distributing information throughout a flexible yet robust delivery infrastructure.” And “More than that, this infrastructure and set of procedures grows out of U.S. government and military interests in developing high-technology communications capabilities (from ARPA to DARPA to dot-coms).” [9] (Ibid 2004) Galloway’s distinction helps us to re-evaluate what he sees as distracting tropes and uncritical interpretations of the Internet, the World Wide Web and Web 2.0.

Thomson & Craighead provide parallel insights through their artwork into the protocols and technical procedures governing the functions of networks. However, human existence and human experience has a relationship with these networks and, out of millions of interactions, evolves not metaphors but fragmented symbolisms and stories. These are telling us about a networked society’s gaze at its mediated self. And this is where art can play a special role in critiquing, communicating and sharing the nuances of this emerging multitude.

The Flat Earth Trilogy presents us with a complexity where everything is flattened out. It maps out a human psyche from an anthropological perspective. And this leaves society to deal with issues concerning the human condition entwined within a machinic evolution.

This evolution has no physical body even if real lives and bodies are its source material “each mode is displaced by machinic evolution, mixing flows and the shifting codes and overcodes of power, the base forms continue onward, written directly into the heart of the system.” [10] (Berger 2014)

To further understand this work in relation to the machinic evolution, the networked gaze, and human interaction, I feel there is some value in considering hyperreality “…a condition in which what is real and what is fiction are seamlessly blended together so that there is no clear distinction between where one ends and the other begins.” [11] Hyperreality is a post-modern term used by Jean Baudrillard, Albert Borgmann, Daniel J. Boorstin, Neil Postman, and Umberto Eco. However, if we add a contemporary flavour to what hyperreality looks like now in a networked society we come up with hyper-mediality. “What we refer to as reality very often is just mediality, and also because that’s how human nature often prefers to observe reality, you know, via some media.” [12] (Ubermogen 2013)

We can see an example of this condition in an artwork by artists’ Franco and Eva Mattes, with their performance video No Fun (2010) [13] where they staged a suicide in the popular webcam-based chat room Chatroulette.

“Notably, only one out of several thousand people called the police. Moving beyond the aspects of shock and provocation, this touches on a basic question: What does “reality” mean in the digital age?” [14] (Eva & Franco Mattes)

The Flat Earth Trilogy throws up many questions and you’d be forgiven for thinking we need another book to fully examine the ramifications of these artworks. Instead let me to refer you to other related texts by Tom Snow, Edwin Coomasaru, Jo Chard, and Alan Ingram by clicking here http://www.inmg.org.uk/archive/thomson-craighead/catalogue/

Shifting Sands.

Clive Gillman in his essay in Flat Earth says “if artists are to find a way to assert a commentary or expression through these emerging forms of contemporary media, they will have to do this by reconciling the resistance of these new media objects to be ordered into a form that may represent a recognisable notion of artistic intent. And it is into this challenge that Thomson & Craighead pitch themselves.” [15] (Gillman 2013)

It is not the audiences who have difficulties with emerging forms of contemporary media it is the mainstream art world, and this is most of its magazines, galleries and museums. From our own experience of showing art and technology at Furtherfield Gallery, audiences tend to be adventurous and open-minded regarding their experiences with technology and societal issues. And yet the art world has had difficulties making a place for this work.

Sarah Cook and Christiane Paul, both curators well versed in the field of media art, have tirelessly offered us convincing arguments why this is. Christiane Paul says, “Many curators and other practitioners in new media seek to “teleport” the art out of its ghetto and introduce it to a larger public.” [16]

Sarah Cook says “artists who are really working with technology are still redefining art. So they’ll always be “in emergence” [..] They always will try to change the boundaries of what we think Art is and challenge the institutions that show it.” [17] This is true with Thomson & Craighead’s installation and networked artwork. It is plugged directly into a larger, expansive, worldly discourse, in contrast to traditional modes of artistic and news presentation which are highly restrictive and contained within their mediated monocultures.

Gillman proposes that Thomson & Craighead are pitching themselves to create art which is a recognisable notion of artistic intent, and other artists should do this also. I am assuming this is so the work is recognisable as ‘art’ to the mainstream artworld and its traditional remits. This is a strange ask if you are an artist who is truly exploring further than what is typically expected by mainstream art culture. I would argue that artistic context and its values are not fixed and that’s the point. If artists become too self conscious in trying to make their art look like an art that “fits”, it then looses its imaginative edge and critical reasoning.

It’s a difficult balancing act if the artist is examining deep or necessary questions whilst the current art world is lagging behind in so many ways. Julian Stallabrass sees this lagging behind as a political issue. In his book Contemporary Art: A very Short Introduction, he critiques the blocking of emergent, and critically engaged artistic expression as part of a ‘New World Order’ where we are constrained by a compliant culture controlled by the rampant demands of a corporate elite, who only consider art in terms of economics, markets and brands. And these restrictive and dominating frameworks are dedicated to the neoliberal promotion of privatisation and growing inequalities.

In his article ‘Reasons to Hate Thomson & Craighead’ he says “At this point, the art professional sees a world crumbling, visions of empty galleries, unique works owned by everyone, a stuttering and then failing of artspeak amid a mass proliferation of ‘work’ and comment, the autonomy of art ruptured, artists and dealers redundant, in short an economy broken and the sacred polluted with the profane. Naturally, representatives of the old order, more or less sharply aware of dark clouds gathering at their horizons, have good reason to hate Thomson & Craighead.” [18] (Stallabrass 2005)

Thomson & Craighead’s work connects with people and they know this because they use content and themes people are thinking about in their everyday lives. This is what makes the series of documentary artworks so powerful. It assembles what is going on in the world in ways that traditional documentary and news channels are not. And this is their real challenge, because if they continue to reflect human culture as it happens with works like October – a documentary artwork about the early rise and fall of the Occupy movement – they will be highlighting messages from a world of people in need of something different than what is currently in place, whether this is deliberate or not. This art has a strange irony, it not only asks us what a documentary is, but it also asks what is news?

The End.

The End is a site-specific artwork first shown at the Highland Institute of Contemporary Art in 2010, Scotland. It is situated in one of the gallery rooms at H.I.C.A that has a large, wall-sized window looking out onto the countryside in the Highlands. It is an intervention into the space where the words ‘The End’ are fixed onto the glass in a style and scale one might associate with the end credits of a movie.

The combination of the outside natural environment, the galley building with its large glass window, and the added text, are assembled together to build a whole artwork. If any these components were taken out of the assemblage it wouldn’t work. This tells us how well crafted Thomson and Craighead’s work is and how much attention is paid to detail.

When looking at The End, one cannot help feeling a little out of sync. It is like a monument or an obituary for a lost world or lost time when we were all standing on solid ground and felt we knew what was real and not real. The End brings into play the rhythms of a larger natural environment and works as a bridge between two worlds or the illusion of it. It reminds us we are no longer experiencing the world face on or directly, but the world is re-introduced to us mainly through screens, televisions, mobile phones and our computers. It also invites us to imagine as we look out on the beauty of the natural world that we are viewing the end of our own role in the story of humanity.

The Situationist, Guy Debord said that people’s alienation was once about having things and claiming better working conditions, but then it moved onto being about a state of appearing. Meaning, it is not producing things, or even owning things that drives society but rather how things appear and how they make us appear. The glass acts as a filter and an interface, a place of safety distant from the touch of the wild. Its physicality, metaphors and symbolism offers a poetic moment for us to consider how perceptions about ourselves and ideas concerning real-life have changed, and what this means.

On the DCA website as part of its commentary about the book, it says Flat Earth presents Thomson & Craighead as pioneers in the field of new media for nearly twenty years. Sarah Cook and Christiane Paul also deserve credit as pioneers for recognising, supporting and dedicating their lives to creating the contexts in contemporary art culture for Thomson & Craighead’s work and other artists’ works. Also, Cook has edited a fine publication. Flat Earth is well designed and the whole book is meticulously well put together with quality images throughout. The mix of inteviews and essays with Thomson & Craighead give the reader a well balanced overview of their the art and their ideas, it is unpretentious and explores their focus as creative and thinking individuals artistically, conceptually and critically. We need many more of these types of books to support this dynamic and ever-changing field.

Thomson & Craighead dig deep into the algorithmic phenomena of our networked society; its conditions and protocols (architecture of the Internet) and the non-ending terror of the spectacle as a mediated life. When reading the Flat Earth publication, you get a clear impression of their conceptual rigour. They know their place and role as artists in society and this is well presented in the book. Their collaborative journey has remained faithful to the World Wide Web, and the Internet as a focal point and a content provider for their art practice.

It would be simplistic to assume they are embracing technology as a celebration of its progress. Their critical scope examines big issues and this is evident in Flat Earth. They belong to a generation of artists who are experimenting with real time data, networks, web cams, movies, images, sound and text; as part of an anthropological venture that studies humanity’s relationship with technology, alongside the inane and profound nature(s) of the human and non-human condition. We exist at a point where ubiquitous computing now redefines our point of presence, shifting our perceptions in reference to cultural tags and repeated experiences of mediation. They successfully critique these changes. Not only to other artists, curators and galleries, but to all who are being transformed by technology and this is what makes them essential and contemporary.

Thomson & Craighead are not just making and showing art they are also presenting questions. These are not invented questions they are already out there. But, just like some need an interpreter to translate different dialogues they are assembling for us the dialogues of an emergent multitude.

Andreas Broeckmann writes on art, machine aesthetics, and digital culture. He is director of Leuphana Arts Program at the university in Lüneburg, and has played key roles at transmediale – festival for art and digital culture, ISEA2010 RUHR, TESLA-Laboratory for Arts and Media, Berlin, and V2_Organisation Rotterdam, Institute for the Unstable Media. Lawrence Bird interviewed him on our current experience of media and civil society. Image: A. Broeckmann, transmediale 2007 (© Jonathan Gröger)

Lawrence Bird: It’s often said that we inhabit the city differently today because of our engagement with media and media technologies. This has been one of your main concerns, and it makes for a very interesting intersection of media theory and public realm theory. Where does this preoccupation come from on your part?

Andreas Broeckmann: I have arrived at these questions not so much from a theoretical or academic perspective, but in response to specific artistic practices that I was interested in. For my own thinking about this area, the works that the artist group Knowbotic Research were working on in the 1990s were seminal. The participative public installation “Anonymous Muttering” (1996), for instance, initiated a radical clash of the physical urban space with the virtual ‘space’ of the internet, interlacing the activities of the participants in a way that created a strange intermediate zone – maybe we could say that it allowed people to place themselves _in_ the medium. In the series of projects that followed under the title “IO-dencies” (1997-99), Knowbotic Research further explored the possibilities of becoming active, of acting in a virtual environment in a manner that was connected to activities and events in the physical space.

I was working quite closely with the group at the time, presenting some of the projects in Rotterdam where I was a curator at the V2_Organisation, co-authoring texts, organising workshops, etc.. This was a great opportunity to think through the issues of the new, hybrid public sphere that was opening up because of the Internet. In order to understand the works, it was necessary to develop a differentiated conception of what it meant to “be public” or to “become public”. The topic returned, for instance in projects I was involved in by Rafael Lozano-Hemmer in Rotterdam, or a publication on Polish video art by the WRO agency, or a major curatorial on a media facade in Berlin, or, for that matter, more recent projects by Knowbotic Research, like “Be Prepared Tiger”, or “MacGhillie”. Personally, I believe that privacy in all its guises – from camouflage and the absence of surveillance to “a room of one’s own” – is one of the great privileges of a modern individual. Contemporary media and communication technologies have transformed the possibilities of being private dramatically, just as the notion of what it means to be public is subject to drastic changes. And artists are articulating these changes which we are all part of, giving us opportunities to reflect on what is going on, and to imagine how things might also develop otherwise. I think that my interest in the relationship between publicness and intimacy is fed both by a personal sense of urgency and and concern, and by the inspiration I get from artists, not to fall into despair.

Lawrence Bird: Fascinating. So would you say that in the direction media are now evolving, there’s actually an increased scope for private “being” — not just in terms of a potential for increased anonymity and independence, but in terms of a richer and more developed individuality? To a greater degree — or perhaps qualitatively different — than was possible in earlier stages of modernity?

Andreas Broeckmann: Unfortunately not… I say that privacy is a privilege exactly because it is becoming such a rare condition these days. The developments that we speak about are, of course, not unidirectional and homogeneous, but very diffused and heterogeneous, and open to quite different interpretations. For many people, a platform like Facebook or Google-Plus is a way of discovering a new form of sociality in which they try out different ways of being public and being private.As for myself, having been brought up with the Critical Theory analyses of the Frankfurt School, I find it difficult not to see these optimistic readings as dangerously naive – it would be a bit like exploring your inner self in the highly regulated and commercial spaces of a shopping mall… I would not go so far as to say that privacy has completely disappered — as though we were now living in a global village of Big Brother containers, or in a vastly extensive version of the Truman Show. But I do think that today we lack a more widespread critical sense of resistance to the regimes of commodification that have taken the place of what were once “privacy” and “social relations”.

Lawrence Bird: You spoke about the concern of “falling into despair”. How general would you say that motivation is? I don’t know if you’ve thought about it this way, but I’m thinking in terms of Occupy, and the other social movements, many of them enabled by media and engaged by artists, which seem to generate new, and some evidence suggests quite lasting, relationships of trust and hope. Many of these seem to come in response to a recent loss of faith in corporations, governments, financial institutions — older social groups that had an important role in old definitions of “public”. I wonder if your comment connects with a widespread yearning for hope, in response to conditions that might well produce despair?

Andreas Broeckmann: I dare not speculate about the longevity of the relationships that have been built by the different branches of the Occupy movement, but I am skeptical about the longevity of anything that is built on specific internet-based media platforms. Facebook, for instance, was launched in 2004, that’s eight years ago, and the German and many other non-English Facebook services are no older than four years. That’s a very short time, and we might want to remember that platforms like Google (*1998), Facebook, Flickr (*2004) or Twitter (*2006) are not part of the natural environment, but recent services offered by profit-oriented companies which, just as well as they may rule the internet world throughout the 21st century, might also get drowned in the swamps of global capitalism (whose regime includes “customer confidence”).

I would refute the assumption, implicit in your question, that many of the people who protested on the squares in Madrid, Cairo, Washington or Athens last year were people who previously had faith in their governments, or the institutions of capitalism. Of course they didn’t, and quite rightly so. What was special about last year was that there is a new, articulate generation of people who would not put up with the situation of stasis, hopelessness and frustration that has paralysed major parts of global societies since 2003 when, in February of that year, millions who took to the streets around the world in protest, were not able to stop the US government and their allies from starting the war on Saddam Hussein’s Iraq. The inflection of this event is different in different parts of the world, but I believe that we share that moment. And this is where the protests in the Arab countries, and those in Spain and Greece, hit the squares on a parallel trajectory: In the same year of 2003, the German government started the implementation of what was called the “Agenda 2010”, a project based on the EU’s 2000 Lisbon agreement of economic restructuring, with the aim of making Europe more competitive on the global market. Since then, in Germany we have seen an erosion of the welfare state, drops in income for lower and middle classes and a huge increase in precarious jobs. But some economists also say that the reason for Germany’s relatively healthy economic situation today, compared with, for instance, Greece or Spain, is that these countries failed to reform their debt-pampered economies. Which is why there is a certain reluctance today in Germany to protect privileges for the Greek middle class, privileges which German citizens already had to give up years ago.

above: Tahrir Square on February 11, by Jonathan Rashad (CC-BY-2.0, 2011).

My point is that if we take things into a more extended historical perspective, and if we count our lives not in short Twitter months, we can see how the struggles, the hopes and the despairs of today are part of a broader set of transformations. And we can see that in these transformations there are forces at work which have a huge inertia and which need to be worked on and battled with both patience and long-term strategies. Like any other revolution, and like in the theatres of the Occupy movement, the one in Egypt may have started on Tahrir Square and the mobilisation of people through media-based social networks, but to complete that revolution, a difficult and drawn-out political struggle needs to be fought. Maybe that is the necessary realisation that hit “the movement” this past winter.

Lawrence Bird: And what form might those long-term strategies take? It’s a huge question perhaps, but do you have any ideas about the shape this restructured public sphere might have to take, what forms of governance and participatory democracy for example, to sustain a more permanent change?

Andreas Broeckmann: Personally, I believe that for the foreseeable future many political struggles will continue to happen in the ‘arenas’ of political institutions like governments, parliaments and other election-based structures, in political parties, public administrations, in transnational and inter-governmental decision-making bodies, in trade unions and NGOs. It is a realm that will only partly be affected or influenced by the online world, and even if the emerging public sphere of the Internet and its social media forums implies a huge expansion and diversification of the mass media dominated public sphere of the 20th century, this expanded public sphere will not necessarily have a bigger impact on political processes than the ‘old’ public sphere did. The experience of the ‘movement’ in Egypt today might be analoguous to that of the APO (the extra-parliamentarian opposition of the students movement) in 1960s and 70s West Germany, i.e. realising the necessity of getting involved in existing state institutions (“the long march through the institutions”), which brought members of that generation to power some 25 years later in universities, in parliaments, in national governments. The relevance and standing of the new Egyptian parties is not proven or disproven in the first elections; it is decided when in ten or twenty years from now they may or may not have been able to change the social consensus about democracy, rights, and freedom.

Lawrence Bird: A confession here: I’m an architect, so I always assume, perhaps naively, that a built infrasructure can play a role in these kinds of transformations. In your opinion, might a material intervention be a necessary part of those changes — distinct from, though perhaps in dialogue with, the mediated public realm? What kind of physical (urban) spaces might serve as a counterpoint or moderator to the transience of the Twitter world — and are those spaces any different from the urban spaces we have now?

Andreas Broeckmann: I doubt whether architecture in the narrower understanding of the term will play much more than a symbolical role in these struggles and transformations. Of course, the built environment, especially the way in which public space is configured, plays a significant role in how public life can unfold in cities. And there are political issues to be fought over: for instance, I find it curious how in many of the European cities the authorities allow the construction of one shopping mall after the other, pushing the social and commercial activity of shopping into privatised and highly regulated control spaces, and then those same authorities are surprised when the neighbourhoods in the vicinity of these malls deteriorate because the normal shops are abandoned or have to be closed, making room for trash and money laundering businesses. The resistance against such developments can at times most effectively be fought in local parliaments that, at least in Germany, have to give their consent to such major construction projects. This makes it necessary to join a political party, get elected into the local parliament, sit around in meetings, deal with all sorts of issues of public interest, etc., and be there when the application for the next shopping mall is up for decision…

Of similar relevance is the designing of the digital sphere through software ‘architectures’ – both in terms of individual applications and services, and in terms of the overall technical infrastructure, both hard- and software, and its governance. The critical discussions around the status of ICANN and, more recently, the public protests against law-making initiatives like SOPA and ACTA, have shown that protests can in fact have an impact on such structures. Yet, that impact will remain cosmetic if the public outcry is not followed up by sustained political work through which the drafting of and the decision-making on such laws is factually influenced. This is what lobby groups do, and this is what social movements also have to do, finding whatever possible and suitable political instrument or institution through which to act.

The major arena of constructing and designing the new political sphere will be in law-making, and I believe that the movement needs critical lawyers, historians of economy and charismatic intellectuals more urgently than architects – although, of course, everybody has an important role to play and no-one who wants to contribute should be sent away.

Lawrence Bird: And how about artists — do they have a role in this? To provoke, perhaps? To articulate social and political conditions? Would you say that whatever that role is, it can be part of the sustained transformation you’re talking about — or do they need to step down into a governance role to take part in that (Vaclav Havel being one example).

Andreas Broeckmann: In my understanding of art, there is no particular role that it can, or even “should” play. I would argue that the most important aspect of art for society is its autonomy and the fact that it has no particular responsibility. Art can beautify, it can decorate, it can irritate, it can disturb, it can question, it can affirm, it can simplify or complicate. Such an “open program” of course implies that individual artists or groups, or specific projects, will take a particular political stand, will try to influence a social or political situation — will seek real impact. This is a form of activism that art can borrow from political groups and movements, but it is not the activism that is crucial for the artistic practice, it is the transgressive articulation that artists may achieve in their own dealing with social realities. I want to emphasize that this is my understanding of art, and I fully respect people who think that art can and must be more engaged in social processes in order to be relevant. But again, I think that what art can give us most importantly is what happens in a zone of freedom that is morally, aesthetically and sometimes also politically more risky than anybody who acts in the political arena — save for the mavericks — would want to be.

So the question, “what should artists do,” can in my understanding only ever be answered: “they should do whatever they do.” It must be the best thing that they can do, they have to be precise in their formulations and realisations, they have to be committed, diligent, and daring. It is wonderful if they can, in that way, help proliferate good ideas and push the political situation in a good direction. But by the same token I believe that it is equally wonderful if artists ask questions that are impossible to answer, or pointing out unsolvable ethical dilemmas, or remove the mask of an opponent only to don it themselves.

There is, in my eyes, certainly no obligation to go into politics like Havel did. Artists are not always people with a high moral reputation, and stepping into the political arena like Havel did requires stamina and a certain habitus. And there are many ways in which people can intervene in social and political processes. Take the example of Aliaa Magda Elmahdy who posted a photograph of herself naked on her website and sparked a huge debate about the situation of women in the Islamic world. This was not an art project, but it shows what work in the realm of symbols can achieve.

Lawrence Bird: If I could I’d like to steer the conversation in the direction of your thinking on “the wild” — perhaps it relates through the transgressive nature of art you’ve just been discussing, and the tricky relationship of that to civic functions, governance, and related realms of responsibility. Cities have been conceived as set apart from the wilderness — within the city lay the realm of humanity, civility, politics; outside its walls, the wild, monsters, raw life. Girorgio Agamben makes the case that the violence of our times equates to the obliteration of that line: between political life (zoe) and bare life (bios).

In light of what you’ve already said about art and transgression, and the value of that; and the precarious status of privacy today, and the danger of that; your understanding of media and the political movements underway today which involve some significant transgression of the boundaries of authority, I’m willing to bet you have a more nuanced take on this issue. What’s our condition now with regards to the edge of the wild? Is it a constantly shifting boundary, what Agamben refers to as the caesura? Does it imply a human condition interdigitated with an inhuman condition, like a werewolf, or cyborg? Does our humanity in fact find its source in the wild?

Andreas Broeckmann: The questions that you raise are of course extremely complex and very difficult to do justice in the current context. So allow me to shirk the anthropological discussion, which I guess I don’t have a particularly original opinion on anyway. When I spoke about the “wild” as an aspect of digital art a few years ago, it was in a half ironic, and half romantic way: ironic in the sense that art that makes use of digital media is technically conditioned and requires a “tamed” environment to function at all; even what is referred to as ‘glitch aesthetics’ is predicated on general functionality, the glitch being only a minor aberration, not a substantial fault. Yet, as you would gather from what I said before, I am also ‘romantically’ attached to the idea of an artistic practice that transgresses these technical functionalities and explores failure, dysfunctionality, misuse, or uncontrollability as categories of aesthetic experience. I’m thinking of artists like Gustav Metzger, Jean Tinguely, Herwig Weiser, or JODI, who in their works perform, we might claim, the potential wildness of technology. This is mostly a controlled, at times even metaphorical wildness, whereas the true wilderness of technology, if we want to go there, is probably the realm of the accident that Paul Virilio has so poignantly written about. An “art of the accident”, as we entitled a festival in Rotterdam in the late 1990s, is, I believe, only possible in the realm of metaphors.

What I’m currently wondering about is whether in our 21st-century cybernated world a notion of “nature” as something different from culture maybe disappears completely, as we have full Google-ised view and total measurability of what happens on Earth, from millimetre shifts of tectonic plates to carbon dioxide output of cattle. In such a world, there would be no room any more for the “wild”, only for different degrees of pollution on the one hand, and endangerment of species on the other…

In the long run I have trust in the finality of all existence, and the futility of all human efforts. But in the short term, that is, in our lives, I believe that we have to work to make the world a little better, or at least do our best to not make things worse than they are.

Since the turn of the millennium, there have been shifts toward new forms of sociopolitical dissent. These include strategies such as cellular forms or resistance including asymmetrical warfare like global insurgencies, the use of social media. Examples would be Twitter and Facebook in their ability to lens dissent for actions in Syria, Egypt and Tunisia, Wikileaks and its ability to mirror, and politics that use anarchistic forms of collective action such as the Occupy Movement. Although my focus is more concerned with the Occupy Movement, what is evident is what I call an amorphous politics of dissent. Amorphous is defined as “without shape”, and can be applied to most of the mise en scenes listed above.

The dissonance of power in regards to conventional politics can be seen in its structure. For example, the nation-state has a tiered, hierarchical structure of power relations. There is a President or Prime Minister, a legislative organ of MPs or Representatives, Parliaments, Houses, and the like, a Judicial organ, and a Military organ that includes any number of militia and police. Although I am referring mostly Western forms of government, we can also argue for the hierarchical form in terms of the Corporation, with its CEO, Board, Shareholders, Managers, and Workers. This can be expanded historically to Feudal lords with their retinue of Vassals, Nobles and Warlords with their coteries of Warriors and support personnel. The point is that conventional power typically operates in a pyramidal command and control hierarchy with a centralized Leader at the “capstone”. One can argue that the pyramid may have different shapes, or angles of distribution of power, but in the end, there is usually a terminal figure of authority. To put it in terms of stereotypical Science Fiction terminology, when the alien comes to Earth, the standard story is that it pops out of the spacecraft and says, “Take me to your leader.” This signifies the hegemonic paradigm of Leadership as the central gestalt of First world power. Leadership, then, is the conventional paradigm of power in Western culture, and dominates the industrialized world.

Territorialization refers to the exertion of power along perimeters, or borders. Functionaries expressing the constriction of territory include customs agents, and border patrols; but are terminally expressed by the military wing of the nation state. This military is also generally pyramidally constructed in terms of Generals, Colonels, and other officers leading Battalions, Regiments and Divisions, which are organized as defenders of a nation’s sovereignty. These military organs are conversely best optimized to exert their power against either parallel or subordinate structures. Parallel structures include the armies of other nations, their Officers, et al, and their troops and ordnance that possess a similar organization. Conversely, subordinate structures over which military powers can exert power over are domestic masses that can be overrun with overwhelming power, although these forces are more specialized (such as National Guards or Gendarmeries). In the conventional sense, power is expressed orthogonally, whether it is against equal or subordinate forces.

Another aspect of this conversation relates to the expression of power/force through conflict and violence, but has its inconsistencies The examples I will use from American pop culture I will use in this missive to explain amorphous action may be violent in nature, but the violent nature of these examples do not relate to the paradigmatic jamming of conventional power. Their citation is related more to the fact of conventional power’s orthogony, or parallelism of exertion of power to similar structures or dominance of the subordinate, and the panic state it experiences when confronted with non-conventional difference or passive resistance. We could express the power relationships between amorphous politics and conventional power in terms of a tetrad in terms of examples of violent and peaceful exertion of amorphous dissent as well as orthogonal conflict. We could cite the Occupy movement as a site of passive, and the Tunisian uprising as violent exemplars of amorphous conflict or dissent. Conversely, the Gandhi/King is a non-violent model of as orthogonal/hierarchical/led action, and World War Two as conventional orthogonal conflict. What is important here is the inability of the conventional politics and power to cope with leaderless, non-hierarchical, non-orthogonal discourse that refuses to talk in like terms such as centralization, leadership and conventional negotiations that include concepts such as “demands”. This is where the site of cognitive dissonance erupts, often resulting in a panic state or in the “figureheading” of dispersed networks of power.

The need for the traditional power structure to focus identity on the antagonist in terms of figureheads is evident in the Middle East and Eurasia in the personification of terrorist and insurgent networks, but is more simply illustrated in the films Alien and Aliens, and Star Trek: The Next Generation. Both of these feature their respective antagonists, the “alien” as archetypal Other, and the Borg, symbol of autonomous, collective community. In Alien, the crew of the Nostromo encounters an alien derelict ship that has been mysteriously disabled to find a hive of eggs of alien creatures whose sole role is the creation of egg factories for further reproduction. At the onset of the franchise, pilot Ellen Ripley is positioned as the “everywoman” placed in the center of cataclysmic events. In the Alan Dean Foster book adaptation, and an extended edit of the Scott film, Ripley finds during her escape from the ship that Captain Dallas has been captured and organically transformed into a half-human egg-layer whom she immolates with a flamethrower. However, in the Aliens sequel, the amorphous society of the self-replicating aliens has been replaced by a centralized hive, dominated by a gigantic Queen that threatens to impregnate the daughter-surrogate Newt. This transformation from a faceless to centralized threat creates a figurehead for the threat and establishes a clear protagonist/antagonist relationship, and establishes traditional orthogony.

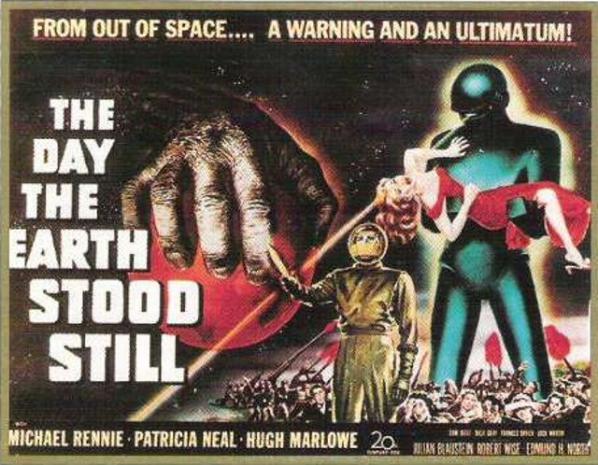

This simplification of dialectic of asymmetrical politics is also evidenced in Star Trek: The Next Generation by the coming of the Borg, a collective race of cybernetic individuals. Although representations of the Borg vary as to fictional timeline, in televised media they began as a faceless hive-mind, which abducted Captain Jean-Luc Picard as a mouthpiece, not as a leader. It was inferred that if one sliced off or destroyed a percentage of a Borg ship, you did not disable it; you merely had the percentage left coming at you just as fast. However, by the movie First Contact, the Borg now possesses a hierarchical command structure to their network and, more importantly, a queen. With the assimilated and reclaimed android Lieutenant Data, the crew of the Enterprise infiltrates higher level functions of the Borg Collective, effectively shutting down the subordinate elements of the Hive. In addition, the Queen/Leader is defeated, assuring traditional figurehead/hierarchy power relations rather than having to deal with the problems of the amorphous, autonomous mass. There are other “amorphous” metaphors in cinema that address the issue of amorphousness. These include the 1958 movie, The Blob, in which a giant amoeba attacks a small town and grows as it engulfs everything. Another is The Thing, about a parasitic alien that doppelgangs its victims, creating another form of faceless threat. Lastly, we have the classic Invasion of the Body Snatchers where alien plant “pods” would bear fruit of duplicates of living people, giving a metaphor for the Communist threat of the Red Scare originating during the Cold War. Perhaps these are historical references to mediated expressions of anxiety in regard to autonomy’s threats to regimented/striated hegemony, stating that this sort of anxiety and terror are not new.

One of the most asymmetric cultural Western interventions in relation to constructs of traditional power is the involvement of Anonymous as part of the Occupy Movement. Anonymous, which has been called a “hacker group” in the mass media, is a taxonomy created on the online image sharing community 4chan.org, arising from the practice of posting “anonymously” unless one wants to use a name, or handle. Although the idea of Anonymous is at best an ad hoc grouping, the use of the “group” name has been ascribed to various factions. According to The State News, “Anonymous has no leader or controlling party and relies on the collective power of its individual participants acting in such a way that the net effect benefits the group.“ The idea of Anonymous fits with the “faceless collectives” mentioned above, and certainly presents an asymmetric, if not non-orthogonal, exercise of power. Anonymous first rose as a voice of dissent that emerged against the Church of Scientology (see Project Chanology), where flash mobs of individuals in Guy Fawkes masks and suits arrived to protest at sites around the world, with boom boxes playing “The Fresh Prince of BelAir”, a popular agitational or “trolling” anthem. It has engaged in other activities, including hacking credit card infrastructures opposed to handling donations to Wikileaks and creating media around Occupy Wall Street. However, without a clear infrastructure and only transient figureheads, Anonymous functions as an organizing frame for a cloud of individuals interested in various collective actions, and represents an indefinite politics based on networked culture. In an expected exercise of force, during the actions against elements opposed to Wikileaks, conventional power struck back wherever it could against members of Anonymous, by arresting over 21, some violently, in July during the actions against credit providers boycotting Wikileaks. This exercise of power was repeated in September, with admonitions about the arrests appearing on YouTube thereafter. Anonymous has also posted videos in support of the Occupy movement. Such a response is not surprising, but is the exact response to non-orthogonal dissent under our model. The problem is that in arresting any number of Anonymous members, traditional power is confronted with the first, distributed model of the Borg that merely exists minus two or twenty members.

Another dissonance between the Occupy Movement and conventional politics is the perceived lack of agenda. This is due to its dispersion of discourse in giving its constituents collective importance in voice. What is the agenda of the disempowered 99% of Americans, or world citizens marginalized by global concentration of wealth? Simply put, the agenda is for the disempowered to be heard. What does that mean? It means anything from forgiveness of student loans to jobs to redistribution of wealth to affordable health care, and so on. It isn’t a list; it is a call to systemic change of the means of production, distribution of wealth and empowerment in political discourse. It isn’t as simple as “We want a 5% cut in taxes for those making under $30,000.” It’s more akin to “We’re tired that there are so many sick, hungry, poor and uneducated, and we want it to end. Let’s figure it out.” It is the invitation to the beginning of a conversation that has no simple answers other than the very alteration of a paradigm of disparity that has arisen over the past 40 years through American capitalism.

The last challenge to the traditional power discourse is that of passive resistance. This is not a new strategy, especially under the aegis of Gandhi and King’s movements. However, it is traditional power’s mere tolerance of nonviolent resistance that does not result in violence. As we can see from the UC Davis assaults and the dispersions after the second month anniversary, conventional power exerts its force against, as Brian Holmes put it, “anomalies” so that the system can be restored and the commodifiable classes are reintegrated into the system to reproduce its agendas. As long as resistance does not present undue inconvenience for the circulation of power and capital, it is allowed. Once it loses its patience with non-orthogonal forces, or if materially sacralized spaces, like Wall Street are threatened, the hegemonic order is reified. The irony of the technical loophole of Zucotti Park being privately owned and having few rules allowed the Occupy movement also highlights the tenuousness of public discourse in Millennial America. However, even with this oddity, on the two-month anniversary of Occupy Wall Street, force has begun to be used against the occupiers as traditional power’s patience grows thin with amorphous politics. In the streets, the marches are split up, and rules about occupation begin to be enforced with cupidity. As said before, hegemonic patience has worn thin, with assaults/dispersions taking place in Oakland, Davis, Philadelphia, and New York, among others. However, the movement moves forward for the moment.

Amorphous politics is based on plurality, collectivism, dispersion and ideas. The hierarchical nation-state has no idea what to do with the amorphous blob as it grows except to try to contain it, but as with Anonymous, it is a whack-a-mole game. If one smacks down one protest, two pop up across town, or five websites pop up on the Net. Shut down Wikileaks, and a thousand mirror sites show up. People in the streets swarm New York and other cities throughout the US, and the world, and conflict arises. Asymmetry and amorphousness are dissonances to traditional power. Ideas in themselves are not hierarchical.

Desires sometimes have no agendas.

Sometimes people want what is right, and all of it.