The New Observatory opened at FACT, Liverpool on Thursday 22nd of June and runs until October 1st.

The exhibition, curated by Hannah Redler Hawes and Sam Skinner, in collaboration with The Open Data Institute, transforms the FACT galleries into a playground of micro-observatories, fusing art with data science in an attempt to expand the reach of both. Reflecting on the democratisation of tools which allow new ways of sensing and analysing, The New Observatory asks visitors to reconsider raw, taciturn ‘data’ through a variety of vibrant, surprising, and often ingenious artistic affects and interactions. What does it mean for us to become observers of ourselves? What role does the imagination have to play in the construction of a reality accessed via data infrastructures, algorithms, numbers, and mobile sensors? And how can the model of the observatory help us better understand how the non-human world already measures and aggregates information about itself?

In its simplest form an observatory is merely an enduring location from which to view terrestrial or celestial phenomena. Stone circles, such as Stonehenge in the UK, were simple, but powerful, measuring tools, aligned to mark the arc of the sun, the moon or certain star systems as they careered across ancient skies. Today we observe the world with less monumental, but far more powerful, sensing tools. And the site of the observatory, once rooted to specific locations on an ever spinning Earth, has become as mobile and malleable as the clouds which once impeded our ancestors’ view of the summer solstice. The New Observatory considers how ubiquitous, and increasingly invisible, technologies of observation have impacted the scale at which we sense, measure, and predict.

The Citizen Sense research group, led by Jennifer Gabrys, presents Dustbox as part of the show. A project started in 2016 to give residents of Deptford, South London, the chance to measure air pollution in their neighbourhoods. Residents borrowed the Dustboxes from their local library, a series of beautiful, black ceramic sensor boxes shaped like air pollutant particles blown to macro scales. By visiting citizensense.net participants could watch their personal data aggregated and streamed with others to create a real-time data map of local air particulates. The collapse of the micro and the macro lends the project a surrealist quality. As thousands of data points coalesce to produce a shared vision of the invisible pollutants all around us, the pleasing dimples, spikes and impressions of each ceramic Dustbox give that infinitesimal world a cartoonish charisma. Encased in a glass display cabinet as part of the show, my desire to stroke and caress each Dustbox was strong. Like the protagonist in Richard Matheson’s 1956 novel The Shrinking Man, once the scale of the microscopic world was given a form my human body could empathise with, I wanted nothing more than to descend into that space, becoming a pollutant myself caught on Deptford winds.

Moving from the microscopic to the scale of living systems, Julie Freeman’s 2015/2016 project, A Selfless Society, transforms the patterns of a naked mole-rat colony into an abstract minimalist animation projected into the gallery. Naked mole-rats are one of only two species of ‘eusocial’ mammals, living in shared underground burrows that distantly echo the patterns of other ‘superorganism’ colonies such as ants or bees. To be eusocial is to live and work for a single Queen, whose sole responsibility it is to breed and give birth on behalf of the colony. For A Selfless Society, Freeman attached Radio Frequency ID (RFID) chips to each non-breeding mole-rat, allowing their interactions to be logged as the colony went about its slippery subterranean business. The result is a meditation on the ‘missing’ data point: the Queen, whose entire existence is bolstered and maintained by the altruistic behaviours of her wrinkly, buck-teethed family. The work is accompanied by a series of naked mole-rat profile shots, in which the eyes of each creature have been redacted with a thick black line. Freeman’s playful anonymising gesture gives each mole-rat its due, reminding us that behind every model we impel on our data there exist countless, untold subjects bound to the bodies that compel the larger story to life.

Natasha Caruana’s works in the exhibition centre on the human phenomena of love, as understood through social datasets related to marriage and divorce. For her work Divorce Index Caruana translated data on a series of societal ‘pressures’ that are correlated with failed marriages – access to healthcare, gambling, unemployment – into a choreographed dance routine. To watch a video of the dance, enacted by Caruana and her husband, viewers must walk or stare through another work, Curtain of Broken Dreams, an interlinked collection of 1,560 pawned or discarded wedding rings. Both the works come out of a larger project the artist undertook in the lead-up to the 1st year anniversary of her own marriage. Having discovered that divorce rates were highest in the coastal towns of the UK, Caruana toured the country staying in a series of AirBnB house shares with men who had recently gone through a divorce. Her journey was plotted on dry statistical data related to one of the most significant and personal of human experiences, a neat juxtaposition that lends the work a surreal humour, without sentimentalising the experiences of either Caruana or the divorced men she came into contact with.

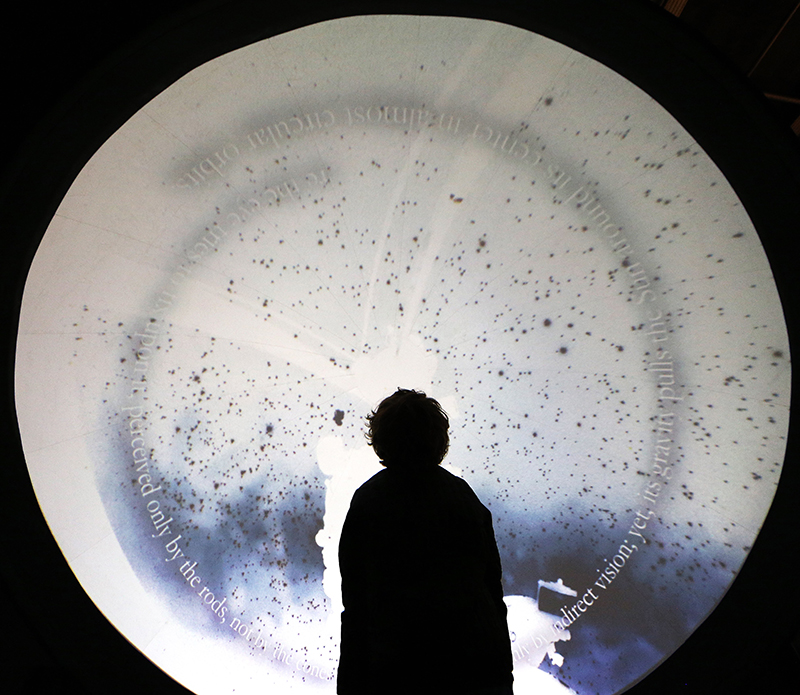

The New Observatory features many screens, across which data visualisations bloom, or cameras look upwards, outwards or inwards. As part of the Libre Space Foundation artist Kei Kreutler installed an open networked satellite station on the roof of FACT, allowing visitors to the gallery a live view of the thousands of satellites that career across the heavens. For his Inverted Night Sky project, artist Jeronimo Voss presents a concave domed projection space, within which the workings of the Anton Pannekoek Institute for Astronomy teeter and glide. But perhaps the most striking, and prominent use of screens, is James Coupe’s work A Machine for Living. A four-storey wooden watchtower, dotted on all sides with widescreen displays wired into the topmost tower section, within which a bank of computer servers computes the goings on displayed to visitors. The installation is a monument to members of the public who work for Mechanical Turk, a crowdsourcing system run by corporate giant Amazon that connects an invisible workforce of online, human minions to individuals and businesses who can employ them to carry out their bidding. A Machine for Living is the result of James Coupe’s playful subversion of the system, in which he asked mTurk workers to observe and reflect on elements of their own daily lives. On the screens winding up the structure we watch mTurk workers narrating their dance moves as they jiggle on the sofa, we see workers stretching and labelling their yoga positions, or running through the meticulous steps that make up the algorithm of their dinner routine. The screens switch between users so regularly, and the tasks they carry out as so diverse and often surreal, that the installation acts as a miniature exhibition within an exhibition. A series of digital peepholes into the lives of a previously invisible workforce, their labour drafted into the manufacture of an observatory of observations, an artwork homage to the voyeurism that perpetuates so much of 21st century ‘online’ culture.

The New Observatory is a rich and varied exhibition that calls on its visitors to reflect on, and interact more creatively with, the data that increasingly underpins and permeates our lives. The exhibition opened at FACT, Liverpool on Thursday 22nd of June and runs until October 1st.