The New Observatory opened at FACT, Liverpool on Thursday 22nd of June and runs until October 1st.

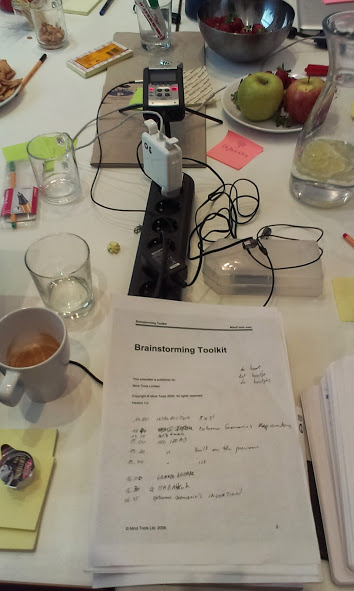

The exhibition, curated by Hannah Redler Hawes and Sam Skinner, in collaboration with The Open Data Institute, transforms the FACT galleries into a playground of micro-observatories, fusing art with data science in an attempt to expand the reach of both. Reflecting on the democratisation of tools which allow new ways of sensing and analysing, The New Observatory asks visitors to reconsider raw, taciturn ‘data’ through a variety of vibrant, surprising, and often ingenious artistic affects and interactions. What does it mean for us to become observers of ourselves? What role does the imagination have to play in the construction of a reality accessed via data infrastructures, algorithms, numbers, and mobile sensors? And how can the model of the observatory help us better understand how the non-human world already measures and aggregates information about itself?

In its simplest form an observatory is merely an enduring location from which to view terrestrial or celestial phenomena. Stone circles, such as Stonehenge in the UK, were simple, but powerful, measuring tools, aligned to mark the arc of the sun, the moon or certain star systems as they careered across ancient skies. Today we observe the world with less monumental, but far more powerful, sensing tools. And the site of the observatory, once rooted to specific locations on an ever spinning Earth, has become as mobile and malleable as the clouds which once impeded our ancestors’ view of the summer solstice. The New Observatory considers how ubiquitous, and increasingly invisible, technologies of observation have impacted the scale at which we sense, measure, and predict.

The Citizen Sense research group, led by Jennifer Gabrys, presents Dustbox as part of the show. A project started in 2016 to give residents of Deptford, South London, the chance to measure air pollution in their neighbourhoods. Residents borrowed the Dustboxes from their local library, a series of beautiful, black ceramic sensor boxes shaped like air pollutant particles blown to macro scales. By visiting citizensense.net participants could watch their personal data aggregated and streamed with others to create a real-time data map of local air particulates. The collapse of the micro and the macro lends the project a surrealist quality. As thousands of data points coalesce to produce a shared vision of the invisible pollutants all around us, the pleasing dimples, spikes and impressions of each ceramic Dustbox give that infinitesimal world a cartoonish charisma. Encased in a glass display cabinet as part of the show, my desire to stroke and caress each Dustbox was strong. Like the protagonist in Richard Matheson’s 1956 novel The Shrinking Man, once the scale of the microscopic world was given a form my human body could empathise with, I wanted nothing more than to descend into that space, becoming a pollutant myself caught on Deptford winds.

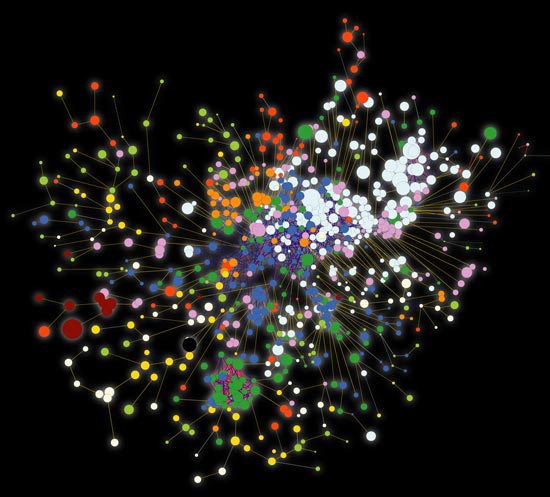

Moving from the microscopic to the scale of living systems, Julie Freeman’s 2015/2016 project, A Selfless Society, transforms the patterns of a naked mole-rat colony into an abstract minimalist animation projected into the gallery. Naked mole-rats are one of only two species of ‘eusocial’ mammals, living in shared underground burrows that distantly echo the patterns of other ‘superorganism’ colonies such as ants or bees. To be eusocial is to live and work for a single Queen, whose sole responsibility it is to breed and give birth on behalf of the colony. For A Selfless Society, Freeman attached Radio Frequency ID (RFID) chips to each non-breeding mole-rat, allowing their interactions to be logged as the colony went about its slippery subterranean business. The result is a meditation on the ‘missing’ data point: the Queen, whose entire existence is bolstered and maintained by the altruistic behaviours of her wrinkly, buck-teethed family. The work is accompanied by a series of naked mole-rat profile shots, in which the eyes of each creature have been redacted with a thick black line. Freeman’s playful anonymising gesture gives each mole-rat its due, reminding us that behind every model we impel on our data there exist countless, untold subjects bound to the bodies that compel the larger story to life.

Natasha Caruana’s works in the exhibition centre on the human phenomena of love, as understood through social datasets related to marriage and divorce. For her work Divorce Index Caruana translated data on a series of societal ‘pressures’ that are correlated with failed marriages – access to healthcare, gambling, unemployment – into a choreographed dance routine. To watch a video of the dance, enacted by Caruana and her husband, viewers must walk or stare through another work, Curtain of Broken Dreams, an interlinked collection of 1,560 pawned or discarded wedding rings. Both the works come out of a larger project the artist undertook in the lead-up to the 1st year anniversary of her own marriage. Having discovered that divorce rates were highest in the coastal towns of the UK, Caruana toured the country staying in a series of AirBnB house shares with men who had recently gone through a divorce. Her journey was plotted on dry statistical data related to one of the most significant and personal of human experiences, a neat juxtaposition that lends the work a surreal humour, without sentimentalising the experiences of either Caruana or the divorced men she came into contact with.

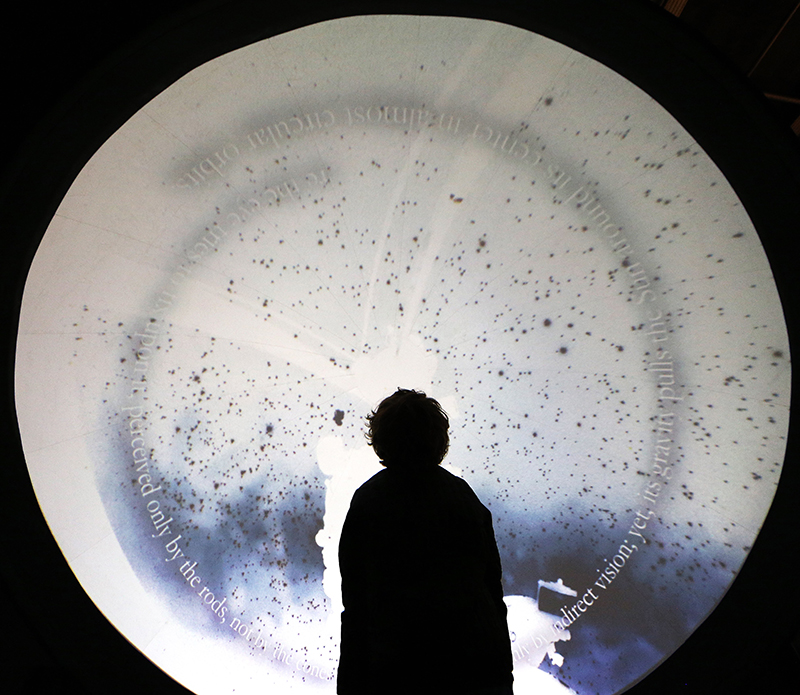

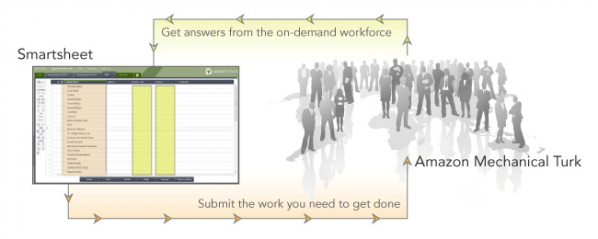

The New Observatory features many screens, across which data visualisations bloom, or cameras look upwards, outwards or inwards. As part of the Libre Space Foundation artist Kei Kreutler installed an open networked satellite station on the roof of FACT, allowing visitors to the gallery a live view of the thousands of satellites that career across the heavens. For his Inverted Night Sky project, artist Jeronimo Voss presents a concave domed projection space, within which the workings of the Anton Pannekoek Institute for Astronomy teeter and glide. But perhaps the most striking, and prominent use of screens, is James Coupe’s work A Machine for Living. A four-storey wooden watchtower, dotted on all sides with widescreen displays wired into the topmost tower section, within which a bank of computer servers computes the goings on displayed to visitors. The installation is a monument to members of the public who work for Mechanical Turk, a crowdsourcing system run by corporate giant Amazon that connects an invisible workforce of online, human minions to individuals and businesses who can employ them to carry out their bidding. A Machine for Living is the result of James Coupe’s playful subversion of the system, in which he asked mTurk workers to observe and reflect on elements of their own daily lives. On the screens winding up the structure we watch mTurk workers narrating their dance moves as they jiggle on the sofa, we see workers stretching and labelling their yoga positions, or running through the meticulous steps that make up the algorithm of their dinner routine. The screens switch between users so regularly, and the tasks they carry out as so diverse and often surreal, that the installation acts as a miniature exhibition within an exhibition. A series of digital peepholes into the lives of a previously invisible workforce, their labour drafted into the manufacture of an observatory of observations, an artwork homage to the voyeurism that perpetuates so much of 21st century ‘online’ culture.

The New Observatory is a rich and varied exhibition that calls on its visitors to reflect on, and interact more creatively with, the data that increasingly underpins and permeates our lives. The exhibition opened at FACT, Liverpool on Thursday 22nd of June and runs until October 1st.

Alan Sondheim has been ploughing a very singular furrow through art, music, writing, philosophy and much else since the late sixties. On the occasion of his participation in the Children of Prometheus exhibition at Furtherfield Gallery we present here an interview conducted by the artist and writer Michael Szpakowski in which Sondheim gives a broad overview of his artistic formation, practice and philosophy.

Michael Szpakowski: I first came across your work through the Webartery mailing list in 2001. I remember being knocked out by your productivity, a productivity that seemed to be allied to an incredible intellectual curiosity and restlessness, resulting in in words, images, movies, music – I remember once you started making little programs in some variant of Visual Basic… All of these posted day in, day out, come rain or shine, to the list… And, obviously I preferred some to others and for anyone to follow every piece of work you made would mean doing little else with their lives, but the quality, the variety, of what you made was ( and remains) staggering.

I found this compulsion to make work both admirable and invigorating and I’ve followed your work ever since. I think I even once compared you to Picasso on DVblog because I couldn’t think of anyone working in art for the net (and every such description is problematic, I’ll ask something more specific later) who seemed to come anywhere near to that fecundity allied to quality too…

I think of this interview as a general introduction to your work for someone who maybe has only happened across it for the first time in the exhibition at Furtherfield so I’d like to ask, first of all, for you to give us a sketch of your intellectual and artistic formation and the milieu(x) in which you have worked (I mean right from the beginning – tell us what makes you, you!):

Alan Sondheim: Of course this is difficult to answer; I began with writing and around the age of 19, started making music as well, but I was always restless. The compulsion has personal roots, but also a desire to move into an environment, habitus, and explore its limitations and promises; in all of this, I’m concerned with the interplay of the somatic and consciousness on one hand, and abstraction, the inertness of the real, mathesis (the mathematization, structuring of the world) on the other. So there’s this dialog at the limits. My first production was a book of experimental writing, An,ode ; around the same time I made three recordings, two for ESP-Disk; this was around the late 60s. Clark Coolidge, the poet, was very important to me early on; I met him at Brown; he introduced me to Vito Acconci and shortly after, early 70s, I moved to NY, eventually SoHo in its heyday. I’ve never been a traditional artist/writer/musician/etc. but move among these areas; I’m concerned with what for me are fundamental issues of philosophy, body, and the world. I want to explore at the limits of what I’m capable of doing. How is consciousness in relation to the world? How is the world?

I’m driven to create daily; while teaching at UCLA, I made a sound film (16mm for the most part) a week for 37 weeks; they ranged from a minute to an hour in length and were forms of deconstructed narrative. Now online, I try to make a work daily in whatever medium, including virtual worlds of all sorts; I continue to try to push limits – what I call ‘edgespace,’ – the space where gamespaces/worlds begin to break down, and what then? (By ‘gamespace,’ I mean, literally the space of a game, where rules hold – for example chess or football. The rules may be consensual or enforced, etc.) This is deeply involved with the politics and somatics of these spaces of course, and on the political spectrum, I’m leftist and deeply pessimistic; I don’t see internet or social media as salvation of any sort, but as fundamentally neutral, extraordinarily adaptable to any number of usages. I’ve written on the differences at the finest levels between the analog and digital, areas like that usually taken for granted; what emerges is a kind of granularity situated within an obdurate real world whose biosphere is faltering deeply.

M: Although you are included in an exhibition in a physical space here the vast majority of your output has been presented on the net, usually in the context of one or more mailing lists. Could you say a bit about this. Was this a conscious choice or pragmatism or somehow both? Is there anything you particularly prize about the rhythm of work and presentation that comes with this kind of platform and has the eclipse of many of the old mailing lists with the rise of social media caused problems for you – have you tried to adapt to/utilise these newer modes?

A: It’s pragmatism combined with a desire to explore; edgespace teeters uneasily and tends towards what I call blankspace, where the imaginary exists – for example, the ‘heere bee dragonnes’ in unknown areas of early maps (I haven’t actually seen the expression, but it serves here). I present my work on Facebook and G+; I also used YouTube for a long time until I was banned from it.

M: Banned from it?

A: A long story that would take this too far afield…

I work well in presentation/talk/performance mode online and off. I believe in the depth of email lists of course. I do think my avatar work is really well suited to gallery spaces; I’ve had up to seven projections going at the same time. I’ve also performed live in virtual worlds or mixed-reality situations which are projected/presenced directly, and for a long time Azure Carter, my partner, and I worked with the dancer/performer/choreographer Foofwa d’Imobilite; the physicality of the work was amazing. And another aspect of what I do – what grounds me – is playing musical instruments, mostly difficult (for me) non-western ones; the instruments require tending and close attention. I tend to play fast. Most of them are strings, bowed or plucked; the music is improvisation. Recently I’ve been focusing on the sarangi, for example. And I’ve had something like 17 tapes, lps, and cds issued; the most recent is LIMIT, which was done in collaboration with Azure and Luke Damrosch, who did Supercollider programming based on concepts I’ve had about time reversal in real time – an impossibility in gamespace, but the edgespace is fascinating. The music products excite me; they’re out there in a way that my other work isn’t.

M: I remember when I first discovered internet art or whatever we want to call it (and there have been numerous quasi theological arguments about this) that there was an intense debate about whether the internet was a conduit or a medium – so many artist-scripters/programmer tended to rather look down on those who simply took advantage of the network’s distribution and dialogical properties (although I have to say that my view is that it was in this massive extension of connectivity that the real force of the thing resided – I remember being told in 2001 that moving image was not internet idiomatic which is amusing given the rise of YouTube &c.) Your work, certainly of the last 17 years or so, strikes me as being intimately tied up with the network and with the unfolding possibilities of new media but not necessarily in the sense that you work with the network itself to make objects, works and more in the second sense of the conduit…

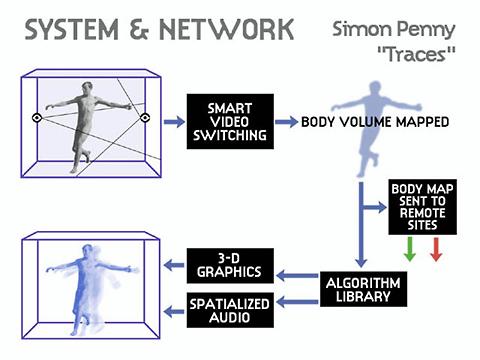

A: It depends; for example one of the projects I initiated through the trAce online writing community in 1999-2000 – over the hinge of the millennium in other words – was asking a world-wide group of artists, IT folk, etc., to map traceroute paths and times from the night of 12/31 to the afternoon of 1/1; the internet was supposed to run into difficulties – over timing etc. – and I wanted to create a picture of what was happening world-wide. A second project somewhat later was using the linux-based multi-conferencing Access Grid system to send sounds/images/&c. from one computer to another in the Virtual Environments Lab at West Virginia University – but these images would travel through notes, much like the old bang!paths, around the entire world. So, for example, Azure would turn her head in what seemed like a typical feedback situation – the camera aimed at a screen, she’s in front of it, the result’s projected on the screen, &c. – but each layer of the feedback had independently circled the globe (through Queensland to be specific), creating time lags that also showed the ‘health’ of the circuit, much like traceroute itself. It was exciting to watch the results, which were videoed, put up online with texts &c.

Part of the difficulty I have is being deeply unaffiliated; I need others to give me access to technology. For example, I’ve used motion capture in three different places, thanks to Frances van Scoy and Sandy Baldwin at WVU; Patrick Lichty at Columbia College, Chicago; and Mark Skwarek at NYU. I also did some augmented reality with Mark, and with Will Pappenheimer. To paraphrase, I’m dependent on the kindness of others; I have no lab or academic community to work among in Providence; what I do is on my own. John Cayley gave me access to the Cave at Brown; Eyebeam in NY (I had a residency there) gave me space and equipment to work with, and in both places I was able to create mixed reality (virtual world/real bodies) pieces – those also bounced through the network…

M: Could you talk, then, a bit about the motion capture/avatar work that seems to have been central to what you are doing over the last ten years or so. I also don’t think I’m mistaken in detecting a very decided move back to music making of late (I know this has always been there but it feels foregrounded again)

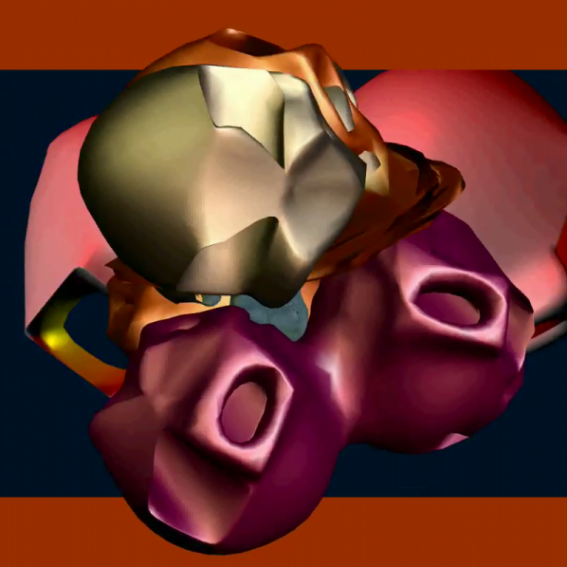

A: The mocap work has been ‘deep’ for me; it involves distorting the entire process, in other words distorting the somatic world we live in. There are numerous ways to do this; the most sophisticated was through Gary Manes at WVU, who literally rewrote the mocap software for the unit they had. I wanted to create ‘behavioral filters’ that would operate similarly to, say, Photoshop filters; in other words, a performer’s movement would be encoded in a mocap file – but the encoding itself during the movement itself, would be mathematically altered. Everything was done at the command line (which I’m comfortable with). The results were/are fantastic. A second way to alter mocap is by physically altering the mapping – placing the head node for example on a foot. But I worked more complexly, distributing, for example, the nodes for a single performer among four performers who had to act together, creating a ‘hive creature.’ All of this is more complicated than it might sound, but the results took me somewhere entirely new, new images of what it means to inhabit or be a body, what it means to be an organism, identified as an organism. This is fundamental. I’m interested in the ‘alien’ which isn’t such of course, which is blankspace. (The alien is always defined within edgespaces and projections; we project into the unknown and return with a name and our fears and desires.)

Most of what I do, for me all of what I do, is grounded in philosophy – ranging from phenomenology to current philosophy of mathematics to my own writing. So these explorations are also artefactual; I think philosophy is far too grounded in writing as gamespace; writing for me, when it’s touched by the abject, the tawdry, the sleazy, the inconceivable, opens itself up.

As far as music goes, I touched on it above in regard to LIMIT. One thing that concerns me is speed, playing as fast as possible, so that the body and mind move on de/rails that are at my limits; I think of this as shape-riding and the results and internal time dilations involved keep me alive…

M: You are genre/practice/technique promiscuous and you have a high level of skill in all –you could equally (and have been) styled Alan Sondheim ‘writer’ , Alan Sondheim ‘musician’, Alan Sondheim ‘maker of moving image work’ (with a marvellous sub-category ‘Alan Sondheim ‘maker of dance related video works’, for a while). Is one of these, in your heart of hearts, central, and, whether this is so or not, how do you place yourself in respect to the various traditions around these areas of work. How do you fit into the art world, into literature or the experimental film tradition? How do you relate to net art/networked art/new media &c.?

A: I don’t seem to fit into the artworld, net art, poetry world, music world &c. – it’s difficult for me to get my work around as a result. Nothing is central but a desire to see how systems form, coagulate, degenerate, collapse, become abject, &c. in relation to consciousness: How are we in the world? On a concrete level, finance enters into the picture; what can I do given a kind of lack of community around me? How can I push myself?

I’m not sure what ‘net art’ is, but certainly the Access Grid pieces &c. are of that, although not of Web-based protocols. There are so many ports out there to use! I do think of myself as a new media artist or someone burrowing into post-media. I’ve always had a few people who believe in what I do, who have helped or worked with me, and I’m really grateful for that. But in terms of institutions, I feel like an outsider artist and am treated like one. It came to a head for me years ago one day when I was living in Soho; I had a call from Vito who said he had realized that whatever I am, I’m not an artist; the same day Laurie Anderson spoke to me and said she realized that whatever I am, I am an artist. So my identity has been far more fluid than I’ve been comfortable with, and it’s affected my career. (There was that tape Kathy Acker and I made 1974, and I read an interview a few years ago, forget the source, with Edit Deak who said the tape wasn’t art at all; in the meantime, it continues to be shown at various venues.)

M: Finally, could you say a little about the work in this particular show?

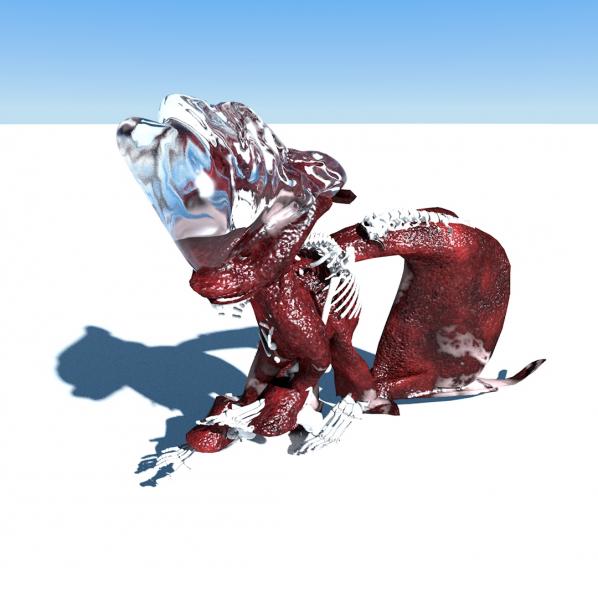

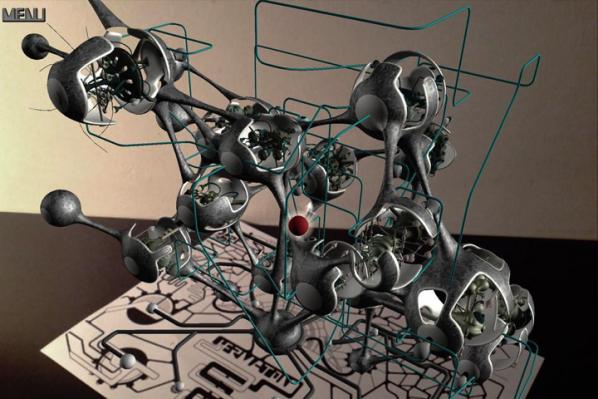

A: The work in the show is a group of 3d-printed avatars distorted through the mocap process described above. For me they connect, deeply, with charred bodies, with anguish, with genocide and scorched earth. They appear also in number recent videos created in various virtual worlds, moving/performing etc. The anguish, so close to death and unutterable pain, is there. I’ve talked about the kinds of brutal killings occurring now worldwide, from Finsbury Park to the United States, the rise, not only of racisms, but violent nationalisms, in the U.S. certainly encouraged by the present regime. I’m sick of it. We all have nightmares. I want to understand this, this grounding in the blooded earth that shakes our very ability to speak, to think, to act.

And yet of course we must resist.

The work in the show is also critical, then, of technophilia, technological answers to the world, utopian dreaming. The top one percent benefit most from the results. I see utopian thinking as dangerous here. Our so-called president has his finger on 4000-5000 nuclear warheads. That’s the reality for me, and why I don’t sleep at night.

Michael Szpakowski: 聽琴圖 (listening to [Alan Sondheim playing] the qin), after Zhao Ji

// gravure, urushi lacquer & pigment on found wood // 30.5X7.5″

Annet Dekker interviews Template, a graphic design and digital development studio run by Lasse van den Bosch Christensen and Marlon Harder. They engage in both client oriented work and initiate their own critical design related projects.

‘The contemporary interface of many digital collections shows images merely in neatly divided grids. How can we create context and meaning for these images?’

As sociologist Mike Featherstone puts it, ‘Increasingly the boundaries between the archive and everyday life become blurred through digital recording and storage technologies’ (2006, 591). Whereas the paper archive has always been the place to store and preserve documents and records, and has functioned as a warehouse for the material from which memories were (re)constructed, its digital counterpart is changing the meaning and function of an archive. The archive’s traditional representational relationship to social identity, agency and memory is challenged by the distributed nature of networked media. Initially designed as a mirror of physical collections and paper archives, the digital repository became a collection itself. A new set of values is presented, but it often remains unarticulated at the cultural and scientific level. What are some of the new understandings of the relationship between the software by which online archives are coded and the social, commercial and organisational practices of what is still considered the archiving of documents? What are the roles of users, in all their manifestations as the meeting point of cultural value and technological systems?

Numerous terms are used to describe the ‘new’ types of archives, for example ‘living archives’ (Passerini 2014; Lehner 2014, 77) or ‘fluid archives’ (Aasman 2014), what is commonly acknowledged is that archives are no longer stable institutions. The terms ‘living’ and ‘fluid’ point to the following characteristic of online archives: openness (they are constantly changing and accumulating), self-reference (hash tags have replaced traditional categorisation), and they represent – like many other online platforms – the shift from passive audiences to active users. Due to their transient quality, it could be argued, these archives are not designed for long-term storage and memory, but for reproduction. As media scientist Wolfgang Ernst explains, the emphasis in the digital archive shifts from documenting a single event to redevelopment, in which a document is (co-) produced by users (Ernst 2012, 95). Whereas the source may remain intact, as in the original archive, its existence is changing and dynamic.

One of the main reasons for this change in archiving is the practice of a variety of non-specialists who are ‘archiving the everyday’ and creating endless ‘personal archives’. This has often given rise to statements about the ‘democratisation of archival practices’, which allows a broad range of individuals, communities and organisations to document, preserve, share and promote (community) identity through collective stories and heritage (Cook 2013; Gilliland and Flinn 2013). What does it mean when archives are thought of in terms of (re)production or creation systems instead of representation or memory systems? Whereas this question has many consequences for thinking about the archive, the design duo Template focuses on how these changes affect the agency of users, by addressing the ways in which users engage with online archives and playfully interrogate and subvert systems such as archives to produce new knowledge concerning their social, cultural and commercial values. With their project Pretty old Pictures, Template addresses the future of online archives and collecting. Whilst critically analysing web 2.0 innovative platforms, particularly Flickr Commons, their aim is to present potential consequences of openness, unclear copyright and ownership legislation, and loss of context in a playful manner.

Template [http://template01.info/] is a graphic design studio established in 2014 and run by Marlon Harder and Lasse van den Bosch Christensen. Marlon studied graphic design as a bachelor at ArtEZ in Arnhem, the Netherlands, and Lasse did his bachelor studies in communication at Kolding School of Design, Denmark. They met during their master studies at Piet Zwart Institute in Rotterdam, the Netherlands. With their studio they both engage in research and client practice. Their research projects often relate to their own practice as designers. For example: how labour, especially digital labour, is in flux and how ‘fun’, playing and making friends are new ways to conceal this. Or how the idea of the creative individual seems omnipresent (everyone is a maker) and how digital ‘template-promoting’ tools are stimulating this tendency. However, they argue, instead of the promised individuality these tools generate a very bland sameness. In their client-based work, they do almost everything that relates to visual communication: from web programming to areas where digital translates into analogue (or the other way around), such as Automated books and the conversion of HTML to print.

Annet Dekker: Can you describe the project Pretty Old Pictures and in what way it represents a ‘new’ archive?

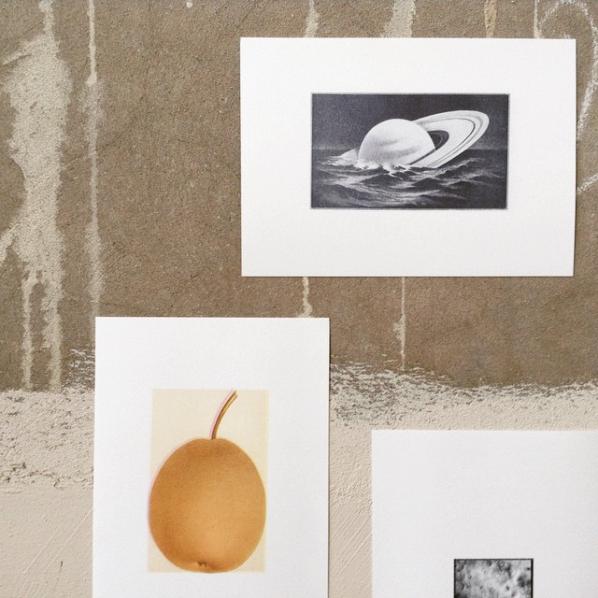

Template: With our project Pretty Old Pictures we are looking into the archive of Het Nieuwe Instituut. Along with many other institutions Het Nieuwe Instituut shares part of its image archive on Flickr Commons. This section of the photo-sharing platform Flickr hosts images with either none or unknown copyright restrictions. The interface of Flickr is extremely visually focused, often displaying an endless amount of imagery lacking any original context. We wanted to explore what potentially can happen to this rather overwhelming content. In a way, these images only exist in the present and attain meaning when a user starts working with them. As such, we believe the ‘present moment’ will very likely become more important in the future where content is extracted from archives and presented as single images unrelated to each other and seemingly without a past. Our intention is to print out specific selections of the images and sell them in nicely packaged bundles.

What were your intentions? What do you want to achieve?

As graphic designers we are fascinated with crowdsourcing platforms and what they stand for: the promise of creative empowerment. You spend four years in an art school learning a trade and then in the real world it is of course not easy to find work. You become part of a broader creative category and especially online there are numerous platforms that turn your trade and your livelihood into un- or underpaid competitions or games, albeit not always in an obvious way. Already at the Piet Zwart Institute [Media Design and Communication in Rotterdam] we became interested in this type of ‘crowd sourced graphic design.’ Take the example of 99Designs. 99Designs is a platform that organises competitions around specific design jobs. For a mere 250 dollars a client often has over 500 designs, made by hundreds of designers, to choose from. For a week we participated in 99 design competitions and made 99 designs that fitted the briefs. During the process we exhibited the designs together with the rejection letters – none of our designs were selected. Rather than being cynical about it, we sincerely wanted to follow this prescribed anticipation of 99Designs and see where it would lead us.

We were interested in how feasible it would be to make the designs, how many hours it would take and in return what our profit would be. Secondly, how much exposure it would generate and if it would broaden our network, which is a main motivation pushed on to designers using these platforms.

Similarly, we looked at other business models like Etsy that all have this same promise of generating an income for your ‘unique products’. When browsing their database it soon becomes apparent that the products are not unique; there even seems to be a very specific Etsy aesthetic. In the end, these platforms tell you more about a specific period in time than anything else. From these experiences we became interested in starting our own company to see how we could benefit from the trend. And then we saw all the content on Flickr Commons and how hardly anyone is using it in the way these other platforms are using content. We wanted to see how easy it would be to make a business out of it: to live the dream of creative entrepreneurs!

Basically we want to comprehend how these institutions are dealing with their digital archives, especially when publishing the content online. In the meantime we confront them with what could potentially happen. There are many possibilities, from selling to copying and changing the images. We want to investigate the consequences of those actions. For example, what does ‘open’ content mean, what are the consequences not only in terms of copyright, but also for the institute and its archival tasks. Are museums following a general trend or are they idealistic about spreading information, or both, and what does that mean in relation to traditional methods? More generally, what are the effects of a changing image culture with regard to new ways of dealing with decontextualized content, appropriation, or even the influence on cultural – and individual – memory? With this project we want to poke at all these issues by actually doing and setting up a business.

At the same time, we are interested in the influence of the online platform that is used. What happens when you give away content to a commercial business, which then becomes a co-owner of the material? This is not necessarily a new question, but it is becoming more urgent now that bigger platforms are offering these easy solutions. In a way it resembles the Google Books project in which many libraries and publishers gave away rights just to have their books digitised. These issues are far less resolved within Flickr Commons, or by those uploading – or downloading – the content. It all happens without people being truly aware of the consequences.

Why did you focus on Flickr Commons, rather then other large repositories, databases, or archives like, for example, Europeana?

We started looking at what sort of external databases and platforms Het Nieuwe Instituut is using, and found out that Flickr Commons is one of the more central, and definitely the biggest. Flickr Commons is interesting because of the promotion of public domain and ‘openness’, using guidelines on copyright that seem purposely unclear. Each image under Flickr Commons is tagged with ‘No known copyright restrictions’, meaning that either the image is in the public domain or that the author cannot be verified or found. Additionally each participating institution has its own rights statement, some of which loops back to the Flickr statement and therefore remains ambiguous or even contradictory. This leaves room for interpretation and opportunities from both Flickr as a platform but also other third parties, like us.

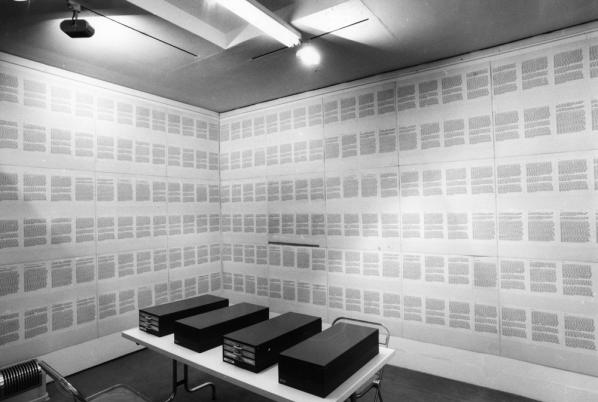

The interface of Flickr also caught our interest. Once you enter the website you see a vast amount of images, infinitely scrollable. Some museums have millions of images on Flickr, which is served up visually as an extremely fragmented image collage. Rather than offering the original context of an image, the system functions primarily through visual linking. That’s how a new context and meaning is made. Of course if you know what you are searching for and manage to type in the right search query you can get relevant results, but this will never match the expertise or human-provided knowledge that is found in a traditional archive. This is what we found fascinating when visiting the physical archive of Het Nieuwe Instituut, where the archivist explained all kinds of relations between documents, offering additional information that you would not necessarily be looking for. We realised what is missing in many online archives or databases right now, and more so in the future, since this kind of human knowledge, built up over time, does not transfer easily. Of course there are descriptions, categories, and keywords based on folksonomies on Flickr, but there are no stories – at least not yet.

Do you use specific criteria for the selections you make?

At first it was merely based on our own favourites. Now we are also looking more at things that are popular, that sell on platforms like Etsy. Often these are the regular things like nature, space, and architecture of course, but we are still testing. For Het Nieuwe Instituut and other institutes partaking in Flickr Commons, Pretty Old Pictures creates custom packages. These are sold in their museum shop, perhaps used as business gifts, merchandise or advertisements. Design-wise we grasp the DIY [Do It Yourself] spirit and this is essential for our strategy. For example, we make our own envelopes for the images we sell, which neatly transforms into an image-frame. They even smell of the laser cutter that we used.

There is such an overall emphasis on all kinds of retro trends, from old school barber haircuts and beards to riso prints on vintage book pages and moustaches on t-shirts. Trends we do not necessarily try to understand, but feed into our project. We are at the same time following the hype and trying to create hype: all in pursuit of a genuine creative business.

What is your relation to the material you selected? Is it ambivalent, or are you complicit – buying into the creative promise?

It is both. On the one hand we feel a bit ashamed, because at times it comes across as ripping someone off. On the other hand we are very excited about the project and looking forward to what may happen. There is a tension between these elements, which we also want to enforce and play with.

Your studio Template also seems to have two sides. On the one hand you make a critical nod to templates and on the other hand your work is about playing and using templates in slightly different ways. Similarly, an interface directs what you can do, and now you are building your own interface. You work seems rather paradoxical.

Yes, we use templates as topics for our research, but then we refuse to use them in our commercial projects. You know templates exist and it is really hard to avoid them. Because of their ease of use it is also completely understandable that people use them. It does not make sense to be completely negative about them. However, of course we like to be critical and subversive in our use of templates. Often the very limited possibilities or options of the template enhance the feeling of having made something. You created something original, that no one ever thought of or will do again. However, you created it within a framework that dictates what you can and cannot do. All these platforms and DIY mechanisms very much play on the assumptions of the importance of the original, the authentic and the individual. Essentially, these are still important beliefs in art traditions and our culture at large.

Most of these discussions also link to the debate on free labour; sometimes you feel in control when using all these readily available tools, but at the same time you are losing your power, because you are giving up the content and work that you create. We have no idea what 99Designs, for example, will do with the 99 designs that we made: they might sell them to different parties, use them to create new templates, or just delete them. Then again, communities get formed on platforms, and seeing other people’s work might in turn benefit you in some way or another. Some platforms even organise special lunch meetings, and the relationships between users have been known to outlive the platform itself. It is too easy to just be dismissive of it all.

Where is the breaking point for you; when will you, or the user, become more powerful than the other?

For us it is important that the design part of the project functions in the way it should. We want to create something that is convincing. In more general terms, it is important how people are addressed, what agency they get and how much freedom they have to use what they created in other ways or places. Of course the failures never receive any attention: the focus is on the success stories as they help promote the platform. That is the point where things start to derail. It may also go wrong when more obvious commercial stakes become apparent. For example, at a certain point Flickr started to sell images from its users licensed under the Creative Commons, causing a scandal amongst angry users who saw their content being commercially appropriated by Flickr. Likewise, we would also be very happy once we can sell the archive back to the organisation to which it belongs! Then again, we would just continue the cynical part of the project, which is not the most interesting part. It would be more interesting to discuss the situation the organisation has created for itself.

I am particularly interested in the idea of sharing and circulating images and other information that is made possible with Flickr Commons as a new form not just of distribution but perhaps also production – and archiving. In what way do you play with these kinds of mechanisms? Do you think it brings out a new potential in archiving?

These collections of images are open, so essentially you can do what you want; digital archiving is really made for interpretations. It demands a much more active role from its audience. They can provide context to the images without having to follow any rules. This would be unthinkable in a traditional archive. At the same time it brings up the question of what the role and function of an archive is. The relation to the past seems to disappear. It is only the present that counts, which is linked to the near future; the excitement of other people’s reactions and how they will respond. Most likely the two ‘archives’ will exist simultaneously, because at a certain point we will need to go back into history. The real question is how we will be able to return to the past in a digital archive, in which context is very scattered, and based of rapidly changing folksonomies rather than standardised categorisations.

In a way it could be argued that your project follows the same ideas as many creative industry start-ups: focusing on future business, economic models and sometimes even utopian perspectives. But at the same time, you work from the present, which may not be obvious to everyone, but is still very relevant as it is changing the way we deal with property, archives and memory.

One of the main things that is often missing in these discussions are the users: they are somewhere in the background, invisible. However, in this project we are replicating this system by focusing on the platform, and not necessarily the users. The physical archive of Het Nieuwe Instituut was a valuable experience for us. It became so clear that the knowledge the archivist possesses is unique and this kind of contextual information is hard to replace in a digital environment. Rather than trying to bring that into a digital environment we wanted to expose other layers, other ways of using and perhaps abusing the content that is void of context. Essentially today’s image culture is hard to grasp, it is partly steered by mechanisms and systems that are working in the back-end, which makes us use images in different ways. Archives are transforming from places where memories are kept to databases in which the present and near future are becoming more important. It is all about the now, presenting and sharing your, or other people’s images with friends and strangers alike. The context of an image is not important anymore; it is all about form and ease of distribution.

This, of course, throws up interesting questions: how do we relate to these images, how does this culture influence us, now and in terms of how we think about the past? Are we taking the image – and its content – for granted? In a way images – and perhaps archives – also become meaningless, or at least the importance shifts in favour of relations and communication between people. We tend to think that selections are still important: similar to the archivist we make selections that may seem random but the constraints generate meaning. Not necessarily the same ‘original’ meaning, but a selection brings something new, it makes people think in a different way about the images. Connections are thought of and narratives appear. Such creative thinking is of course easier with a selection of five than with hundreds of images. This new way of dealing with the content of the archive is no longer related to singular objects but meaning is generated through different constellations. Similar to oral culture, events and histories are now retold in different ways. As such it could be argued be that the (future) digital archive has more in common with oral traditions than with its paper version.

Pretty Old Pictures is commissioned by Het Nieuwe Instituut as part of their ongoing research ‘New Archive Interpretations’ (curated by Annet Dekker). For more information see http://archiefinterpretaties.hetnieuweinstituut.nl/en

Template are part of the exhibition: “Algorithmic Rubbish: Daring to Defy Misfortune” @ SMBA in Amsterdam, with Blast Theory, James Bridle, Constant Dullaart, Femke Herregraven, Jennifer Lyn Morone, Matthew Plummer-Fernandez, Template, Suzanne Treister. The show runs till 23 August with a final day discussion that includes Template and Constant Dullaart, moderated by Josephine Bosma. For more info: http://smba.nl/

Featured image: A is for Art, B is for Bullshit: A history of conceptual art for badasses, book by Guido Segni 2015

“Outside of the Internet there’s no glory” Miltos Manetas”

Guido Segni, is an Italian artist whose activity began in the fields of hacktivism and Net Art in the 90s. As part of his practice he questions the nature of identity that resides on the Web (acting under many fake identities, like Dedalus, Clemente Pestelli, Guy McMusker, Angela Merelli, Anna Adamolo, Guy The Bore, Umberto Stanca,Silvie Inb, Fosco Loiti Celant, Guru Miri Goro, Leslie Bleus, Luther Blissett) and the value of digital activity with projects like 15 Minutes, anonymous, and The middle finger response.

The Internet and lists are two things that have always been together, especially now many of us use social networking platorms such as Twitter and Facebook. We can’t track how and when the first “Top 25/10/5” appeared on the Web, but it’s for sure one of the most frequent ways to gain a lot of attention from Internet users, and it can make you feel as if you’re trapped in a never ending, online fast-food loop. However, when I found out that Guido Segni had created his own version of a top 25 list I was naturally intrigued, so I decided to ask him what it was all about.

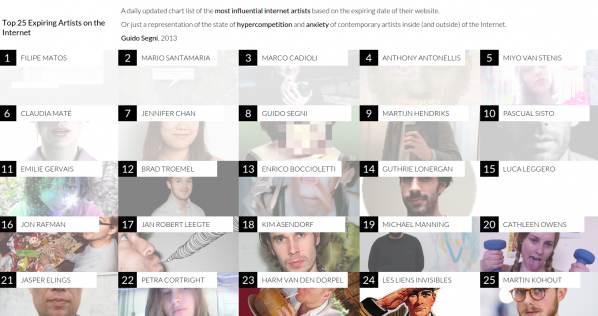

Filippo Lorenzin: How and when did you start working on Top 25 Expiring Artists?

Guido Segni: It all started in 2013 after a discussion with Luca Leggero, an artist friend of mine who was working on a piece about the ephemerality of internet art pieces, and it stimulated in me many thoughts on the subject. In the beginning I just wanted to create a sort of memento mori, a list of all artists’ expiring websites. It was only a few months later I introduced the idea of it as a competition, transforming the work into an ironic top artists ranking list, based on the expiration date of their websites.

FL: Could you tell us how it works and how are artists ranked on the list?

GS: It works as many of the other ranking lists you can find on the web. The difference stands on the criteria. While many lists circulating on the web (Top 10 young artist to follow, Top 5 internet artist, etc) are often based on unintelligible criteria, in TEIA (Top Expiring Internet Artists) the criteria are as clear as useless and absurd: the whole list is in fact ordered by the expiration date of the artist website. The nearer is the website expiration date, the better ranking the artist website will obtain. It’s a democratic but very competitive race where everyone can reach the first position even if just for a day. Top 25 Expiring Artists is automagically updated every day – you can only see the top 25 but actually the project counts more than 50 artists. To be included in this list an artist just needs to make an email submission sending the URL of his/her/its website.

FL: This work has many interesting points to talk about, but I would start with lists-related questions. Does ranking artists on the basis of their aim to be not forgotten mean to highlight a typical behavior of all online users or does it specifically relate to web-based artists?

GS: Actually, the piece is mainly focused on web-based artists. Working with digital based technologies, I’ve always had to face the problem of ephemerality: every year I need to renew the subscription to the hosting service of the many website I own, I periodically have to upgrade the technical environment of my works and often I also need to recode them from scratch in order to keep them all working. That’s why I decided to transform this everyday battle with technology into an ironical and nonsense race for artists, aiming to survive to time.

FL: In the list there are only artists mostly interested in digital issues and I know most of them by person. I have even worked with some of them in previous years and this makes me quite comfortable, like if it was more a sort of reunion with old friends, rather than a competitive race. Is this part of the project or would you like it to be more harsh?

GS: Remember the list is a top 25 Internet artists, so it was natural for me when I started the project to choose the first group of artists mainly involved in digital issues. That said, apart from that memento mori feeling which I’ve discussed before, I was also interested in creating a believable and ironical representation “of the state of hypercompetition and anxiety of contemporary artists inside (and outside) of the Internet.” Probably it’s because I’m a nostalgic of the early days of the Internet – the period of the net utopia – but what I see today is more and more a rising feeling of egotism and selfishness. So what I tried to do is just to stress this contraposition between the brotherhood – what you call the reunion with old friends – and the competition, a perpetual struggle between peers for not being forgot.

FL: This project is ironic. You can say this just by seeing how you mimick aesthetic and text styles of online services like Klout or Google Rank. It seems to me that this is a recurring feature in your works – like in The Middle Finger Response. Is it true?

GS: It maybe depends on the fact that I’m from that particular area in Italy (Tuscany) where you can’t either take yourself too seriously. Or maybe it depends on the fact that irony itself is an important feature you can find over all the formats on the Internet. But I agree with you that willing or not the use of irony is a recurrent and strong component of my works.

FL: I’m interested in how people (me too, yes) sign to online services that promise them to rank their online lives on the base of their influence capacity. It’s like watching a mirror made on quantification premises, built by the same system that push you to post more and more about yourself and your incredibly unique existence. In which way this project is related to this phenomenon?

GS: The main intent of the project is to ridicule lists of any sort. But said that, I think the reason why lists – as a cultural form – are so popular is that they have the power to simplify the representation of complex phenomena of reality. So the various “Top artists to discover”, “Top 10 rock bands” or the “Most influential person in the world” are just examples of a fictious narration which give the apparent comprehension of the real. And this is particulary true in an over-polluted space like the Internet.

FL: In the brief conversation we had previously on Twitter, you said to me that you would like to make other versions of this project. Can you tell me something about this?

GS: I have many ideas about these new versions but unfortunately I’m a very slow man and I still don’t know how and when they will be released.

FL: You worked on the branding of people also with 15 Minutes, anonymous. Could you tell us if and how there is a connection between that work and Top 25 Expiring Artists?

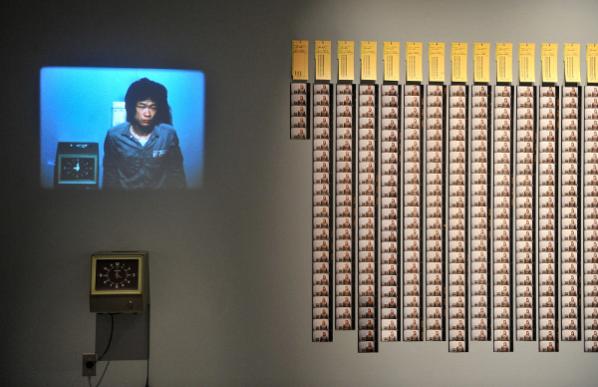

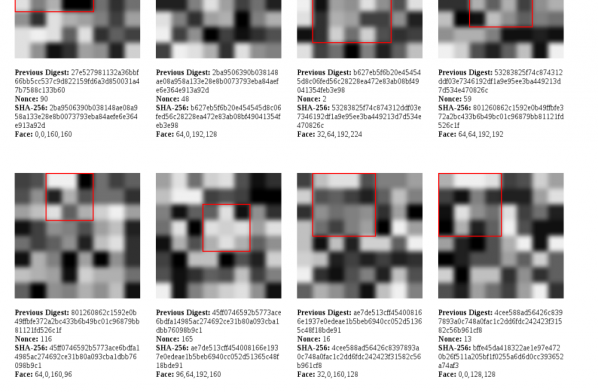

GS: To be honest, at that time I hadn’t in mind these connections. From a certain point of view I think they are very different form each other, but it’s true that they both implicitly move around the concepts of fame and anonymity in opposite directions. While in Top 25 Expiring Artists the expire date is an ironic way to reach a sort of fame – even if only for a day – in the case of 15 Minutes, anonymous I focused on the algorithmic aspect of transforming a very large number of pictures of pop symbols into anonymous and abstract pictures.

FL: Again, the anonymity and the individual are two of the main questions in your research. This happens also with Proof of existence of a cloud worker, and I recall me Middle Finger Response. What do you think?

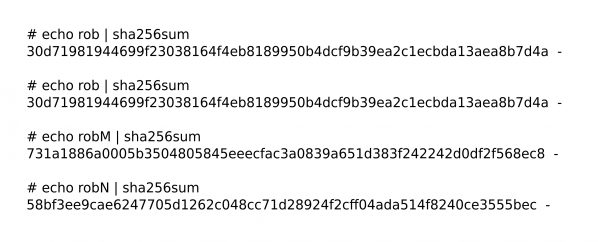

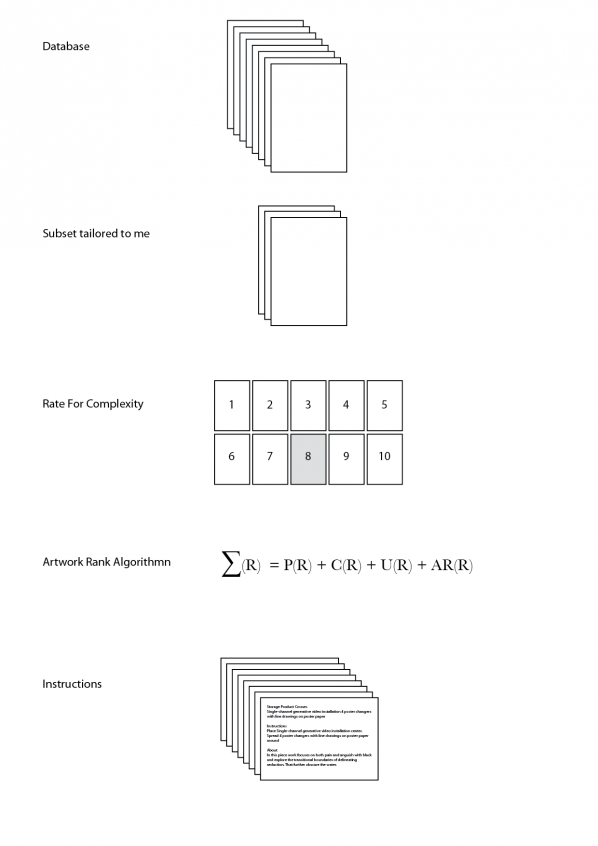

GS: Between 2013 and 2014 I made several experiments with crowdsourcing and, yes, Proofs of existence of a cloud worker and Middle Finger Response have many points in common apart from that they are projects based on Amazon Mechanical Turk platform. Basically they both document and display what crowdsourcing is from the point of view of the workers dispersed through the new digital frontiers of leisure and labour. I think you got the point when you talked about anonymity and individual. As all the efforts of crowdsourcing platforms are to hide and anonymize the crowd, what I tried to do is to give them back a face and a voice. In The Middle Finger Response I focused on the spontaneous pose and gesture captured by the webcam, while in Proofs of existence of a cloud worker I used a more abstract and apparently nonsense approach as I asked them to re-enact a clip found on YouTube which shows a person claiming “Pics or it didn’t happen”.

FL: What will you be doing in the future?

GS: As I’ve already said I’m a very slow guy and I’ve been working on this particular project for almost 2 years. But I think we’re almost there and in a few months I’m going to release it. It’s a project about failures, datacenters, space/time travels and desertification of communications. Stay tuned 😉

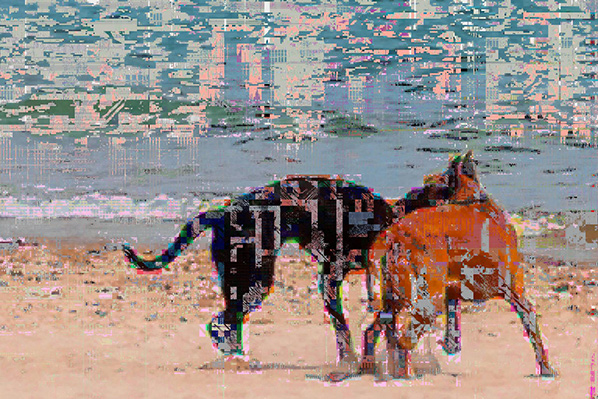

Structures. Something has been built, grown, stretched. Maybe skin, maybe a web, maybe a protective barrier – it is a plastic protein emitted by an organism in order to increase its survival opportunities, it is a food matrix for its offspring which thrive on glossy resin. You can travel across it and it can easily be mapped, although not by humans.

We can’t say anything about it – we can speculate everything about it. It is something possible or as the author says another reality. The real is replaced by the potential. This is one of a series of works by St. Petersburg-based artist Elena Romenkova. The works are glitches, abstract distortions, alien expressions of what for her is a subconscious realm.

A portal. You are entering the rainbow world contained within two concentric eggs within the grey world. This is light, reflections, haze, indescription. It looks inviting. The colour spectrum is odd, the whites creep up on everything else, the shape of everything is strange. Basic synaesthetic rules are inapplicable at the rainbow/grey world junction.

There is nothing that this image, by French artist Francoise Apter (Ellectra Radikal), has in common with Romenkova’s. They are united only by their adherence to strangeness, a technically created vista that looks like nothing we know. A world not of local cultures, but of computational production. Here anyone can know anything, it doesn’t matter where you’re from.

What is culture when locality is secondary to epistemology? What is knowledge when the portable device takes precedent over your situated environment? Worlds are built around us, sophisticated electrical spaces, they travel where we travel, and only after do we factor in the idiosyncracies of specific geography. If the banal experience is one of nomadic alienation, of search methods based on no place, what does the role of culture and art become? Everyday life is a subject for hypothetical language. The digital commons is a species of posthuman that communicates via speculative misunderstanding.

Korean artist Minhyun Cho (mentalcrusher) shows us what the dinosaurs really looked like. When you put the meat and scales back on. He shows us what an ice building being looks like in the shadow of terminal cartoon winter. How rubber can be used to erect sculptures and bones can be taken out of museums and put to good use in civic architecture. No one is around to see this, but still the idea sets a precedent. Crown each ghost with ice mountain prisms.

With visual language, very quickly we get to a stranger and more indeterminate range of science fiction possibilities than narrative tends to map out for us. How much imagination is possible, and how much does our internal experience match anything presented around us. If our environments advance exponentially quicker than any generational or traditional mythology, what sort of language can we have for expression? The maker’s invention precedes the reception of form. Innovation is a matter of banal activity, communicating an experience of the real which is never the same.

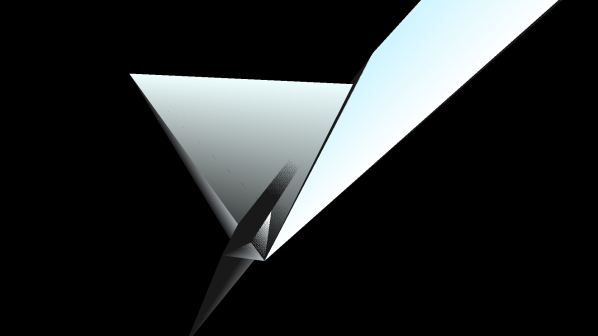

And now an eyeball. Triangles. A vessel. To Cho’s blinding world of light, Spanish artist Leticia Sampedro responds with a featureless darkness. All absurdities once on display, now they recede into nothing. It might be a mandala, perhaps an artifact from the ancient future, a portable panopticon that fits conveniently on your desktop. Your feelings are here, your peculiar distances, everything’s reflecting off the glass, the metal, the camera. You are the mirrored fragments of an invention we’ve lost the blueprints to. Foresight the womb of a disembodied politics of community.

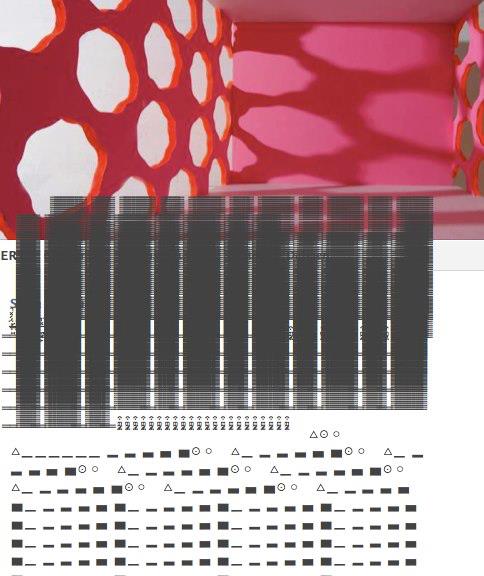

Community held together by structures. In German artist Silke Kuhar‘s (ZIL) work, we enter into one of these structures. Inside we find hallways, a nice selection of windows and all kinds of data – scripted, graphed, symbolized. This is the plan for the future. I hope you can read what it says. Her work meshes spaces with collapsing foreign constructs – if we can just read the language we’ll know what to do. But no one reads it, and no one wrote it. This is a building without inhabitants – architecture without people. Democratic ballots are automatically filled out by a predetermined algorithm. Your agency is a speculative proposition for popular media – people collaborate with you, but they can’t be sure where you are, when you wrote, and if you really exist as such.

No people. This is a unifying principle. Cold, silver, streams. Machines in the sky. Silicon waterfalls, diagonal. Civilization distilled into physical patterns, an obtuse object photographed in another dimension. What is the word for reality again. What is the word for scientific investigation? A Venezuelan based in Paris, Maggy Almao’s abstract glitch world is silent – it’s a gradient, it’s some illusion of partial perspective.

What is the language to talk about the world? If we turn to artists’ visualizations, what does that tell us about languages we speak, and ones we read? What does the graphing of incomprehensible mechanisms tell us in turn about art and its history? The machine’s narratives tend to drown out any functional reality. Genre storytelling tropes become repurposed as collective cultural ideas. Conceptual works are followed by pragmatic speculation, medium-centric analysis replaced by experimental failures. You can never get a fictional experiment to work.

Science has indelibly entered the art field, for each of its medial innovations it requires further attention in terms of its technical makeup. Half the work is figuring out what the canvas even is, we are building canvases, none of them look alike, and their stories read like data manuals. An aesthetics of unknown information.

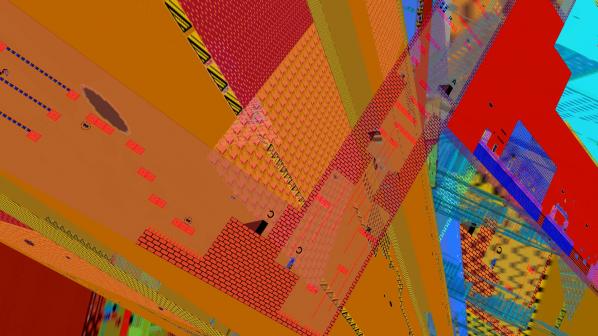

This is the homeland. The homeland is mobile and has many purple bubbles. It’s an airship from the blob version of the Final Fantasy series. It has satellite TV to keep in touch with the world. It has some tall buildings so you know it’s civilized. It is part of Giselle Zatonyl, an Argentine-born Brooklyn-based artist’s opus which deals comprehensively with science fiction ideas and their implications.

The ship travels, where the culture originates is more and more unknown. It is technically divided, access is the key, we can worry about language and culture later. We are still embodied, still located somewhere, but all this has become subject to the trampling of scientific mythologies, where their utilities might go, and where their toys are most needed. Crisis is a genre now, about as popular as time travel. You are now free to dream up whatever future society you wish, and subjugate whatever cyborg proletariat your heart desires. In the realm of speculation, anything is possible, and nothing is fully acceptable.

The themes of internet art production give us some language, some set of visions that tell certain stories – works found throughout the internet, posted in communities, shared online – sometimes part of gallery exhibitions or products, sometimes not. You get a profile, some social media pages, build a website, you begin making, sharing and remixing images. Folk art is a subsidiary of new media art – social sculpture meets internet content management systems. A language for political engagement based on the creative activity of speculation. Scientific dreams for a technological commons.

Dreams where sight is physicalized into complex data graphs. Where Sampedro’s portable gelatin panopticon is cloned into a regularized matrix. Inspired vision is just one aspect of algorithmic predictability. In Taiwanese artist Lidia Pluchinotta‘s visual work, the cloned image is central. Mechanical reproduction, skulls, spirals, symbols, the internet has it all. Civic participation has never been so mathematical, observation never so multiple.

Inside the city, architecture is actually a colour-coded map that helps you find the store you’re looking for. The map is the territory except there’s no info on how to read it. We are here, we are home, but the walls of the buildings were designed by some specialist that we haven’t met yet. Stairs, depths, the complex and layered constructions in Canadian artist Carrie Gates‘ work aren’t quite one of Zatonyl’s buildings. More fragmented, more saturated, more chaotic. It’s speculated that people could live here, although we don’t see them anywhere. Not yet anyway.

The maelstrom of technological progress presents us with the need to adapt our participation and rhetoric accordingly. Science fiction is a folk language for common experience within a technoscientifically oriented world. These images are imaginative products of social and participatory artist communities who, when marrying the personal and contextual, create speculative objects of general strangeness. Their description is nothing less that one of alien entities – alien entities that are everywhere. Earth is the most sophisticated foreign planet we’ve yet to invent, we just need to discover how to populate it.

Those were the words I noticed when interviewing Augmented World Expo organizer Ori Inbar several days before AWE2015, the trade show of Augmented and Virtual Reality. “We’re not in beta anymore…” Inbar said, “We now have companies implementing enterprise-scale Augmented Reality solutions, and with coming products like the Meta One and Microsoft HoloLens, the consumer market is being lined up as well.” With the addition of the UploadVR summit to AWE2015 the event was a blitz of ideas, technologies and new hardware.

AWE/Upload is a trade and industry event that also includes coverage of the arts and related cultural effects, although it is smaller when compared to the industrial aspect of the show. In this way it is similar to SIGGRAPH and this is much of my rationale for covering this, and also SIGGRAPH later this year? Doing so is as simple as McLuhan’s axiom of “The Medium is the Message” or, better yet, examining how developers and industry shape the technologies and cultural frameworks from which the artforms using these techniques emerge. The issue is that in examining emerging technologies we can not only get an idea of near-future design fictions but also the emerging culture embedded within it.

To put things in perspective, Augmented Reality art is not new, as groups like Manifest.AR have already nearly come and gone and my own group in Second Life, Second Front, is in its ninth year. Even though media artists are frequently early technology adopters, what appears to be happening at the larger scale is a critical mass that signals the acceptance of these new technologies by a larger audience. But with all emerging technologies there is drama driven by those industries’ growing pains. For AR & VR the last two years have certainly been tumultuous.

Last year’s acquisition of Oculus Rift by Facebook sent ripples through the technology community. Fortunately, unlike my upcoming example, the buyout did not eliminate the Rift from the landscape; instead it gained venture capital allowing for licensing of the technology for products like the Sony Gear VR. Also the current design fictions being distributed by Microsoft for its Hololens give tantalizing glimpses of a future “Internet of No Things” full of virtual televisions and even ghostly laptops. This was suggested in a workshop by company Meta and the short film “Sight”, in which things like televisions, clocks, and objective art might soon be the function of the visor.

However disruptive events also happen in the evolution of technologies and their cultures. The news was that scant weeks before the conference a leading Augmented Reality Platform, Metaio, was purchased by Apple. Unlike the transparency and expansion experienced by Oculus the Mataio site merely said that no new products were being sold and cloud support would cease by December 15th. In my conversation with conference organizer Ori Inbar we agreed that this was not unexpected as Apple has been acquiring AR technologies, which has been related in rumors of “the crazy thing Apple’s been working on…”; But what was surprising was the almost immediate blackout, part of the subject of my concurrent article “Beware of the Stacks”. For entrepreneurs and cultural producers alike there is a message: Be careful of the tools you use, or your artwork (or company) could suddenly falter in days beyond your control. Imagine a painting suddenly disintegrating because a company bought out the technology of linseed oil. Although this is a poor metaphor, technological artists are dependent on technology and one can see digital media arts’ conservative reliance on Jurassic technologies like Animated GIFs for its long-term viability, but to go further I risk digression.

Another remarkable phenomenon this year was the near-assumption of the handheld as a experience device, and their use seemed almost invisible this year. What was evident was a proliferation of largely untethered headsets, ranging from the Phone-holding Google Cardboard to the Snapdragon-powered (and hot) ODG Android headset, boasting 30-degree field of view and the elimination of visible pixels. In the middle is the tethered, powerful Meta One headset with robust hand gesture recognition. Add in the conspicuously absent Microsoft Hololens and the popular design fictions of object and face recognition are emerging.

That is unless you are a brave early adopter, developer, or enterprise client. The fact that there was an entire Enterprise track and Daqri’s release of an AR-equipped construction/logistics helmet made it clear that the consumer market, much more prevalent last year, has clearly been placed in the long-term. For now, consumer/artistic AR is largely confined to the handheld device, as experienced through Will Pappenheimer’s “Proxy” at the Whitney Museum of American Art or Crayola’s “4D coloring books” in which certain colors serve as AR markers. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing, as an audience is likely to have a device that can run your app through which they can experience the art. As an aside, this is the reason why I chose to use handhelds for my tapestry work – imagine trying to experience a 21’ tapestry with a desktop using a 6’ cord! At this point, clarity and function, both partially dependent on computer power, have created a continuum from strapping your iPhone to your forehead like a jury-rigged Oculus for under $50, to potentially using a messenger bag with the Meta at $512, to the expensive ($2750), hot, but elegant ODG glasses you might try on if you visit the International Space Station.

While discussing the general shape of technology gives a context for its content and application, a media tool is often only as good as its app. Without meaning to show favoritism, Mark Skwarek’s NYU Lab team has been going outstanding work from a visualization of upcoming architectural developments to a surprising proof of concept for a landmine detection system, which I thought was amazing. Equally innovative was the VA-ST structured light headset for the visually impaired, which has several modes for different modes of contrast. These alternate methods not only was surprising in terms of application and possible creative uses but also changed my perception of AR as possessing photorealistic, stereoscopic overlays.

Other novel applications included National Geographic’s AR jigsaw puzzle sets, of which I saw the one outlining the history of Dynastic Egypt. I felt that if I were a kid, building the puzzle and then exploring it with AR would seem magical. There are other entertainment and experimentation platforms coming online like Skwarek, et al’s “PlayAR” AR environmental gaming system. But one platform I want to hold accountable for still being in late beta is the” LyteShot” AR laser tag system, which got an Auggie Award this year. My pleasure in the system is that the “gun” per se is Arduino-based, meaning that it could be a maker’s heaven. It uses the excellent mid-priced Epson headset, but at this time it is used primarily for status updates although there is a difference between AR and a heads-up display. So, from this perspective, it means that there are some great platforms getting into the market that are highly entertaining and innovative, but there are a few bugs to work out.

For the past thousand words or so I have been talking about the industry and applications of AR, but for me, my “soul”, if you will, set on fire during the “idea” panels and keynotes. For example, on the first day, Steve Mann, Ryan Janzen and the group at Meta had a workshop to teach attendees how to make “Veillometers” (or pixel-stick like devices to map out the infrared fields of view of surveillance cameras. Mann, famous for creating the Wearable Computing Lab at MIT and being Senior Researcher at Meta, still seemed five years ahead of the pack, which was refreshing. Another inspirational talk was given by one of the progenitors of the field, and inaugural Auggie Award for Lifetime Achievement, Tom Furness. His reflection on the history of extended reality, and his time in the US Air Force developing heads-up AR was fascinating. But what was most inspirational is that now that he is working on humane uses for augmentation systems such as warping the viewfield to assist people with Macular Degeneration. This, in my opinion, is the real potential of these technologies. In fact this array of keynotes was incredible, with Mann, Furness, the iconic HITLab’s Mark Billinghurst, and science fiction writer David Brin, (who comes off near-Libertarian) gave vast food for thought.

Every year, the Augmented World Expo gives out the “Auggie” awards for achievements in technology, art, and innovation in AR. I think it should be noted that the Auggie is probably the world’s most unique trophy, consisting of a bust that is half naked skull and half fleshed head with a Borg-like lens with baleful eye wired into that head. The Auggie is another aspect of AWE that signals that the world of Reality media is still a bit Wild West.

There are several categories from Enterprise Application to Game/Toy (LyteShot having won this year), and many of them are largely of interest strictly to developers. For example, the fact that Qualcomm’s Vuforia development environment won three years in a row gives hint to its stability in the market, and Lowe’s HoloRoom is a wonderfully strange mix between Star Trek and Home Improvement. The headset winner was CastAR, a projective/reflective technology where polarized projectors were in the headset instead of cameras, which worked amazingly well. The other winners were gratifyingly humane applications such as Child MRI Evaluation and Next for Nigeria (Best Campaign). The prizes impressed on me that the community, or part of it, “got it” in terms of the potential of AR to help the human condition, which is perhaps a “superpower” that the conference framed itself under.

Being that I am writing this for an art community it would be of interest to know where the art was in all of this. The Auggies have an Art category, as well as a gala between the end of the trade show events and the Auggie Awards. The pleasant part about AWE’s nominations for the best in AR art is that those works have integrity. Manifest.AR regular Sander Veerhof was nominated for his “Autocue”, where people with two mobile devices in a car can become the characters of famous driving dialogues (“Blues Brothers”, “Pulp Fiction”, “Harold and Kumar”). Octagon’s “History of London” is reminiscent of the National Geographic puzzles, except with far greater depth. Anita Yustisia’s beautiful “Circle of Life” paintings that were reactive to markers were on display in the auditorium but, besides a Twitter cloud and a Kinect-driven installation, the art was swamped by the size of the auditorium.

The winner of the art Auggie, Heavy & Re+Public’s’ “Consumption Cycle”, (which this writer saw at South by Southwest Interactive) was a baroquely detailed building sized mural of machinery and virtual television sets. I feel a bit of ambivalence about this work, as Heavy’s work tends to rely on spectacle. Of the lot I felt it did deserve the Auggie, purely for its execution and the effective use of spectacle. But with the emerging abilities of menuing, gesture recognition, and so on, I felt that last year’s winner, Darf Designs’ “Hermaton”, employed the potentials for AR as installation in a way that was more specific to the medium.

Yes, but it was in a much smaller area than the AR displays. There were standout technologies, like the Chinese Kickstarter-funded FOVE eye-tracking VR visor, a sensor to deliver directional sound, and Ricoh’s cute 360 degree immersive video camera. The Best in Show Auggie actually went to a VR installation, Mindride’s “Airflow”, where you are literally in a flying sling with an Oculus Rift headset. Although a little cumbersome, it was as close to the flying game in the AR design fiction short, “Sight”. So, in a way, the ideas of near-future design and beta revision culture are still driving technology as surely as the PADD on Star Trek presaged the iPad.

This year’s AWE/UploadVR event showed that reality technology is emerging strongly at the enterprise level and it’s merely a matter of time before it hits consumer culture, but it’s my contention that we’re 2-4 years out unless there’s a game changer like the Oculus for AR or if the Meta or ODG get a killer app, which is entirely possible. So, as the festival’s tagline suggests, are we ready for Superpowers for the People? It seems like we’re almost there but, like Tony Stark in the beginning, we’re still learning to operate the Iron Man suit, sort of banging around the lab.

Choose Your Muse is a new series of interviews where Marc Garrett asks emerging and established artists, curators, techies, hacktivists, activists and theorists; practising across the fields of art, technology and social change, how and what has inspired them, personally, artistically and culturally.

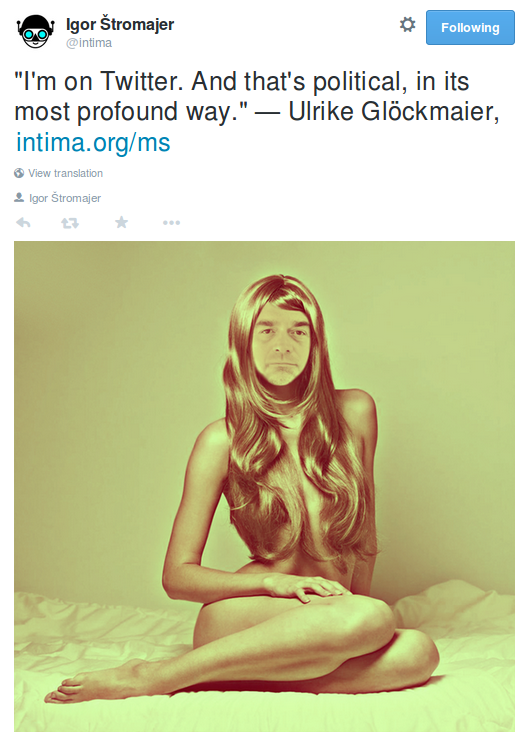

Since 1989, Igor Štromajer aka Intima has shown his media art work at more than a 130 exhibitions, festivals and biennials in 60 countries. His work has been exhibited and presented at the transmediale, ISEA, EMAF, SIGGRAPH, Ars Electronica Futurelab, V2_, IMPAKT, CYNETART, Manifesta, FILE, Stuttgarter Filmwinter, Hamburg Kunsthalle, ARCO, Microwave, Banff Centre, Les Rencontres Internationales and in numerous other galleries and museums worldwide. His works are included in the permanent collections of the Centre Pompidou in Paris, the MNCA Reina Sofía in Madrid, Moderna galerija in Ljubljana, Computer Fine Arts in New York, and UGM.

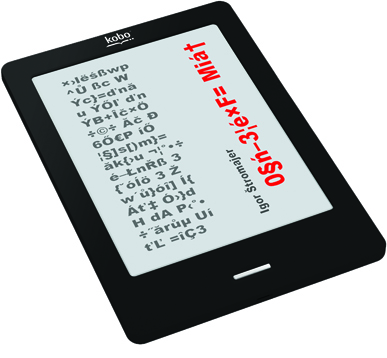

Available as:

– PDF file 0sn-3iexfemiat.pdf (2.7 MB, 206 A4 pages)

– EPUB file 0sn-3iexfemiat.epub (884 kB); Open eBook Publication Structure (Kobo etc)

– mobi file 0sn-3iexfemiat_mobi.zip (994 kB); Kindle (3 files: mobi, apnx, mbp)

Marc Garrett: Could you tell us who has inspired you the most in your work and why?

Igor Štromajer:Ajda Likar, Aleksandra Domanović, Alexei Shulgin, Ana Isaković, Andy Warhol, Angela Washko, Anne Magle, Anne Roquigny, Annie Abrahams, Annika Scharm, Antonin Artaud, Aphra Tesla, Bertolt Brecht, Bojana Kunst, Brane Zorman, Brigitte Lahaie, Carolee Schneemann, Chantal Michel, Charlotte Steibenhoff, Curt Cloninger, Diamanda Galás, Dirk Paesmans, Dragan Živadinov, Falk Grieffenhagen, Florian Schneider, Fritz Hilpert, Gabriel Delgado-López, Georges Bataille, Gertrude Stein, Gianna Michaels, Gina Spalmare, Gretta Louw, Henning Schmitz, Ida Hiršenfelder, Immanuel Kant, Italo Calvino, Ivan Jani Novak, James Joyce, Jerzy Grotowski, Jim Punk, Joan Heemskerk, Johann Sebastian Bach, John Cage, John Lennon, Jorg Immendorff, Josephine Bosma, Judith Malina, Julian Beck, Karl Marx, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Kazimir Malevich, Lars von Trier, Laurie Anderson, Laurie Bellanca, Lucille Calmel, Ludwig Wittgenstein, Luka Prinčič, Marcel Duchamp, Margarida Carvalho, Maria Winterhalter, Marie-Sophie Morel, Marina Tsvetaeva, Marisa Olson, Marjana Harcet, Marko Peljhan, Martine Neddam, Matjaž Berger, Minu Kjuder, Morena Fortuna, Nam June Paik, Nana Milčinski, Netochka Nezvanova, Nika Ločniškar, Olia Lialina, Peter Luining, Philip Glass, Ralf Hütter, Robert Görl, Robert Sakrowski, Robert Wilson, Robin Dunbar, Ronnie Sluik, Sergei Eisenstein, Simone de Beauvoir, Srečko Kosovel, Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz, Stanley Kubrick, Suvi Solkio, Thor Magnusson, Ulrike Susanne Ottensen, Varvara Stepanova, Vesna Jevnikar, Vladimir Mayakovsky, Vlado Gotvan Repnik,Vsevolod Meyerhold, Vuk Ćosić, Yevgeny Vakhtangov.

MG: How have they influenced your own practice?