This is the third of three pieces on people who are posting work to the photography sharing site Flickr [1].

In this final article I look at the work of Karin Rudolph

. Rudolph is a Belgian photographer, currently living in Athens, where she works as a wedding and event photographer and raises two teenage sons. In addition to her work for pay she makes an ongoing series of ‘personal’ images which she regularly posts to the photo sharing site Flickr.

I ask her to send me some images from a wedding job and she does.

It is a job she is clearly good at—everything is beautifully shot, nicely framed, sharply in focus (when sharp focus might be thought necessary), but there is that extra something that comes with a good portrait photographer, which I can only describe as fellow feeling. A fellow feeling which elicits transparency and a willingness to risk vulnerability from the subject. I’ve never met Rudolph but it’s clear that her personality, her way of being, is a player here.

There’s also a sharp curiosity at work—a hunger for the way the world looks and with Rudolph this seems to become attached to particular objects, creatures (some human, some not) and roles. There was a dog at the wedding in the images she sent me. The wedding took place outdoors and the clearly much loved animal figures in a number of the shots. It’s as if at one point R becomes fascinated by it and we get shots where the all humans are cropped (in the shooting; she doesn’t crop after the fact) down to the waist and the dog becomes central (although a small child has a supporting role here too since he necessarily evades the crop/frame wholesale). We get a dog narrative. Then a bouquet catches her eye and we get a bouquet narrative, the wedding filtered through a non-human being or an object. Motion—a sense of the moment before and the moment after being necessary, if hidden, components of this still image—is a key underpinning of so many of these images, particularly in relation to these micro-narratives.

In a photographer less manifestly gripped by the facts of our fragile human being and ways in the world one might call some of her approaches formalist. It is certainly true that rhyme, echo, geometry, continuities and disruptions of line, shape and colour play a highly significant role in the structuring of her images but one of the driving forces of R’s work is that it constantly moves to dissolve any artificial divide between content and form. Yes, her eyes seek pattern; yes, this or that organising device might order an image but this never obscures our awareness of the facts, feelings and relationships portrayed or implicit there. Also—we humans are formalists, aren’t we? We’re pattern seekers. We play. Were you never fascinated as a child by mirrors, by the world turned upside down by hanging from your legs or by the cropping or heightening, or focus) achieved by looking through the cracks in your fingers? Of course you were. As we grow we perceive the whole world through a complex dialectic of what is presented to our senses on the one hand and our burgeoning sorting and structuring principles on the other. We are of necessity creatures of content and form together and one surmises that this is what makes us creatures of art too.

I’d been writing and thinking about this piece for a few months, on and off, and I’d got to a second or third draft when it hit me with a thud, a jolt, that hardly any of the recent images have titles.

The fact had just sailed under my radar, curiously, since I’ve argued and will again, that insofar as we can talk about meaning in a photo (or any visual artwork) this possibility lies in a network of references and comparisons which ineluctably involves talk, writing or both. Language. Further, that visual art is best seen as something humans do (emphasis on both words) than as the usual set of isolable ‘in and of themselves’ objects (which isolation is a fiction, at best an analytical convenience). And then it struck me ( I was being struck a lot that day) that there is something about these images that fights back against language—they’re often cross genre and resist categorisation and there’s a sense in which the easiest approach to what’s in them is simply to list it, and finally to say that this image had these things in it under this kind of light from that angle but, of course, this is far from satisfactory and at root there is something far transcending taxonomy or description going on. But –dammit! –I can’t help feeling it is as if the images (placed as they are in the sequence formed by Flickr) are calling out, hailing each other. I don’t know why, but forced rhubarb, a most unlikely image, is the one which springs to mind and persists, as if the absence of the immediately adjacent language of a title somehow forces the set of glorious but hitherto mute images to invent speech.

Anyone who has ever taken an un-posed image of a human being on a fast shutter speed will be cautious about ascribing emotions or characteristics to the subject on the basis of what is revealed. As in so many other ways, the very small, the very distant or unreachable, animal locomotion, the photograph reveals things beyond our normal ability to see or grasp them. One of these things is the curious plasticity of the human expression and how in our interactions we read this in sequence, in time, together with a host of other clues, aural and visual, to make sense of what is going on, to try to understand both what a person is doing and to surmise what they might be feeling . (Of course the opposite of this, the posed image, brings its own problems too.)

When we think hard and soberly we cannot but be convinced that the photograph alone, an impossibly small fragment of time, does not allow us enough evidence, that it is somehow unanchored in the world.

And yet, the desire to draw conclusions, to make comment, is certainly strong in us and each photographic image of a person, especially the striking and affecting ones, comes with a very strong sense that we are able to do so.

What can we actually say about the still photographic portrait, both in general and in particular cases?

One thing we might say is that the single image’s apparently complete account of a human being, based upon a fleeting expression (and perhaps the fleeting expressions in response of others and maybe also the presence of contextualising objects or other clues) suggests at best, a class of possibilities. This single image evokes a range of other possible images and moments in the world at least one of which must correspond to our strong intuitions about it. So even if we were able to establish the facts of the matter in this particular case and it made a lie of our emotional response , nevertheless that response represents a truth and somewhere, perhaps quite often, in the world, situations occur, have occurred, will occur, which correspond to this truth.

And it seems to me that it is this instinct for general human truth, allied to the particularity of light, line, composition, of other things depicted, which manifests in the eye-and-heart-catching-ness of the resulting final image.

A strong way of putting it would be that any portrait is just as much a work of fiction as a novel but that as we would not wish to deny something called ‘truth’ in the novel ( you might—I see no point to the thing otherwise) in the portrait we work our way back to truth.

And at least for me it is the photographer’s—and here, now ‘the photographer’s’ means R’s—capacity for empathy, for narrative, for understanding of the world and the wonder and the oddness of its inhabitants that makes her such a good portraitist (and let’s not forget, too, simply having done the thing a lot —this is often underrated nowadays.)

Do I know whether the Orthodox priest at the wedding table was a kind man? No. I don’t. I cannot. Is kindness manifest in the photo, is the possibility of kindness in the world reasonably asserted in it? Do I know more about kindness thereby? Absolutely.

There’s a black and white image, taken, I think, at the place where her teenage sons practice their footballing skills which feels like a short story or perhaps a collection of short stories, each cued by the various human presences which form at one and the same time a large (in how they capture our attention) and a small (in how much actual area of the image they occupy) part of the entire image.

It also has a most clearly defined geometry—three strips, the topmost being the practice field itself, the middle appearing to be a road like depression running between the photographer and this field and the lowest a pavement of some sort on the other side of that ‘road’. The almost bizarrely long evening shadows of R and a companion (and the horizontal distance between shadows is nicely ambiguous on the exact relationship between those shadowed) stretch forward into the image. The vertical grid adjacent to them, with a gap in the centre picked out in shadow too, suggests they are standing at a pedestrian gate to the place. I imagine the figure at the viewer’s right is R as the arms appear to be raised in a photo taking action.

(The image thumbs its nose at genre—it is oblique self-portrait, landscape, social history, portrait and exploration of geometry and structure all at the same time.)

Shadows aside, the figures which catch my eye (what about you, so much to choose from or are you constrained in a similar way to me by something in the way the image is structured?) are the short stocky man in motion, walking away from us at the image’s far right top strip foreground. There’s a delicious swagger and confident openness about him.

Has he passed through the gate where R stands? Did he greet her?

The second key (perhaps because nearest?) figure is the young man, top strip, viewer’s far left, again in movement, this time almost certainly certainly sports related. Is he pursuing a stray ball? Running to greet a friend? Engaged in some sort of running warm up/exercise? As we strain to see, our relationship to the image’s scale shifts and we begin to realise just how many other figures he opens up to us—there are at least six either standing or seated in those little sheds at the field’s side between him and the left edge of the nearest goal net—each an enigma of a small but definite kind—and when we move rightwards from them we realise (and we have to move closer in, look differently, at the image to see this) just how many people there are in some sort of action here. As we move out again we are stuck by the contrast between the contemplative calm of the giant shadows and the anthill busyness of the young men. And here’s another thing. This is such a male photo. (With the exception of the photographer and I think it’s only because I know she is female that I read her as such. Then even as I write this I notice the slight head-cocked-to-one-side quality of aficionado-like attention in the head of the left shadow—and why do I think that might clue maleness? What does that say about me?) Oh! Layers and layers of fact, of presence, of things to enumerate and puzzle over. So much! And this before we take the thing as a totality—geometry, inhabitants, shadows, activity, motivation, time of day, distant trees, weeds and barren ground, a sky whose colour we can only guess from the fact we know there is evening sun. And that totality is the hardest thing to compass in any way other than an intake of breath or shiver down the spine. Enumerating the contents helps (although it’s not essential to the immediate affective apprehension of the whole—that just happens) but it’s the inexplicable (not a value judgement—literally inexplicable—simply, ‘This is what R did’) decision to frame those contents in that way—the bit of the process which defies words—that makes this and so many other pieces by her so powerful.

5.

A ravenous eye.

She has a ravenous eye, constantly tracking the scene in front of her and hungry for detail. This hunger does not distinguish between content and form. Whatever is human, whatever stirs affect or curiosity—whether pattern, rhyme or echo, or ethics, or suggested human warmth or frailty, this is swallowed up and processed by heart and mind in turn

The resulting images bear the strong feel of certain, almost objective, structuring principles—that following of object or creature within a scene, the use of rhyme and echo. Two further categories are geometry and colour (and nothing here is pure, there are no essences, sometimes blocks of colour impose an extra, parallel geometry upon a scene whose first order sense—whether it be human beings in action or traces of interpretable human activity; buildings, signs, the street —apparently lies elsewhere.) The key thing about all these structuring principles is that they are found, excavated, discovered, seen—not made. They happen in parallel with, arise out of the actions and feelings of, human beings in this world, the only one we have.

Because she is someone who has lived, fully, in that world, for a fair time, because her hunger extends beyond the visual (she always has a book on the go and the range of these is impressive), because she has a number of languages and is at home in at least three cultures, she makes images which are connected and re-connected by hundreds of threads to things we ourselves might have read and thought or experienced and talked about. Further, it is impossible to imagine that the fact she is a woman living in a country not of her birth, where she has learned a different script, different ways of talking and being, where she works in part as an image maker for hire and constantly both connects and holds separate that work for pay from own ‘own’ work, at the same time as raising children by herself, that these facts are not also somehow foundational.

For a long time I have struggled with how to attach the word meaning to image. It is too easily and glibly used. An image never ‘means’ a single thing (unless it is the poorest of images and even then the human capacity for/delight in ambiguity sets to work to disrupt this) What is evident in Rudolph’s work is networks of evoked meaning, memories, feelings.

Her way of being in the world, this following her eye and nose, means that there is a kind of metonymy purged of any attempt at system—here is a dog or child or chair or window. Here are the things which necessarily were near it at a moment in time and this is how they were disposed. There was reason and there was randomness. Parts of the disposition were beautiful. (What do I mean by beautiful? They move me, they fill me with a joy that cannot be reduced to words though it perhaps can be limned by various combinations of words, combinations potentially infinite which always nearly but not completely fail.) Parts of the disposition were stark or threatening or at least worrisome. The bringing together of all these parts—worry, beauty, pattern, action—into an image framed, bounded, lit, by the laws of the heart and the laws of the intellect now pulling one way, now the other. The work about the world is itself part of the world. We are not alone. No person is an island. We can read each other’s thoughts. We can feel each other’s feelings.

The words and the image and human heart and human history dance ever outwards and outwards. What does an artist do but always start to write the whole history of humanity in the world?

Compiler is an experimental platform organised by curator Alisa Blakeney, artist-curator Tanya Boyarkina, artist Oscar Cass-Darweish and choreographer Eleanor Chownsmith, all currently students of MA Digital Cultures, Goldsmiths. The platform is being built in order to “support collaborative, process-driven projects which connect artists and local communities in networks of knowledge-exchange”.

The organisers of Compiler describe it as a kind of ongoing prototype, a structure constantly negotiating the openness to maintain links to varied practices with the coherence of framing, containing, and describing some of the complicated products of digital-analogue interactions. Their focus is looking at what ‘digital culture’ means and having a productive conversation about it.

From 6-8 April, the first Compiler, Play Safe took place downstairs at OOTB in New Cross. The exhibition examined practices of surveillance inherent in “states, corporations, technological spaces and the idioms of digital art”. It questioned whether an increasing intensity of surveillance is linked to control, extraction and politics, or can be understood as a pleasurable phenomenon. People were invited to “Dance a website, see through the eyes of a computer, and have our cryptobartender mix you a cocktail to cure your NSA woes”. The work on show, made by students from MA Computational Arts and MA Digital Cultures (both Goldsmiths), included Eleanor Chownsmith’s software and performance which turned website HTML into dance routines, Michela Carmazzi’s photographic project documenting the reactions of Julian Assange and his supporters following the United Nations’ ruling about his case, and Saskia Freeke’s machine which repeatedly and intentionally failed to create a ticker-tape parade using sensors and fans.

An exhibition on the theme of surveillance creates a strange grey area for itself when shown in a building with nine screens of CCTV footage. Oscar Cass-Darweish’s project made a fairly direct link to the CCTV cameras which emphasised this greyness. The project produced a rendering of the exhibition space by using a function usually found in motion detection processes. This function calculates the difference in pixel colour values between frames at a set interval and averages them, creating a visual output of how machines calculate difference over time.

Another work which made links with the room upstairs was Fabio Natali’s Cryptobar, where following an interview with the ‘bartender’ about your data privacy needs you were recommended a cocktail of data-encryption software. Upstairs you could buy, and drink, a cocktail with the same name (the Cryptobar was part of the V&A Friday Late on Pocket Privacy on 28 April).

So far, Compiler has made a variety of spaces for conversation about digital culture through both its artworks and its organisation. Each artwork has a different ‘footprint’ of interactions, linking websites to rooms, success to failure, data privacy to financial transaction via consultation, and making interesting connections between CCTV and code, dance notation and HTML, activism and commerce.

An interesting way to read the Compiler platform is as a series of combinations of human-readable codes and machine-readable codes. The platform ‘compiles’ a different combination each time, and each time the output is different. Through this, the interaction of analogue and digital processes is demystified and muddled, in a distinct way. The platform is in its early days, but it seems likely that new connections and new grey areas will appear over the next few months, as Compiler has its second exhibition (again at OOTB) in May, takes part in the CCS conference at Goldsmiths in June and heads in other directions thereafter.

The exhibition offered plenty to play with, while posing complicated problems in relation to openness and experimentation. When I spoke to Eleanor, Tanya and Alisa about Compiler and its aim to engage local communities in networks of knowledge-exchange , we talked about how it’s an impossible and strange aspiration to have a ‘neutral’ venue. While a cocktail can be delicious and engaging, it’s also expensive. While a cafe is, arguably, a less exclusive space than a gallery, OOTB itself is a cafe which targets a specific audience. Drink prices, decor and a host of other factors mean OOTB, like all spaces, is politicised in a particular way. Their venue choices so far will influence, in subtle and overt ways, their future attempts to engage diverse local communities. The organisers of Compiler acknowledge this; their response is that rather than trying to make an artificial neutrality they are keen to move as the platform develops to new spaces and new and different contexts.

A change of context, message, communication style is not easy; nor does it fit with to an easily recognisable politics or aesthetics. Moving into and out of contexts is something to be done carefully and thoughtfully. It seems to me that the Compiler team will have their work cut out, but if they can direct that work in such a way that the platform is able to communicate in multiple ways at once, ‘networks of knowledge-exchange’ could develop between, and in response to, the markers set by the organisers. The question is, how will they develop?

Artist collective THEY ARE HERE invite you to play with and test software that allows wireless-enabled computers and mobile devices to directly form a spontaneous communication network independent of the internet.

Across a series of drop-in sessions facilitated by THEY ARE HERE, games and experiments will be trialled as part of the development process for their forthcoming exhibition at Furtherfield in October 2016.

These activities will take place online & offline around Finsbury Park.

Please bring a wi-fi enabled device to the workshop and if possible download the software Qaul.net in advance (qaul.net/software.html.)

No experience is necessary. Each session will be a discrete event, so you can attend as many or as few as you care to.

Join THEY ARE HERE at any of the following meetings at Furtherfield Commons, Finsbury Gate, Finsbury Park.

Session 1: 3pm Sunday 14th August 2016

Session 2: 3pm Sunday 28th August 2016

Session 3: 3pm Sunday 11th September 2016

Session 4: 3pm Saturday 24th September 2016

You must be aged 16 yrs +

Email contact(at)theyarehere.net for further information.

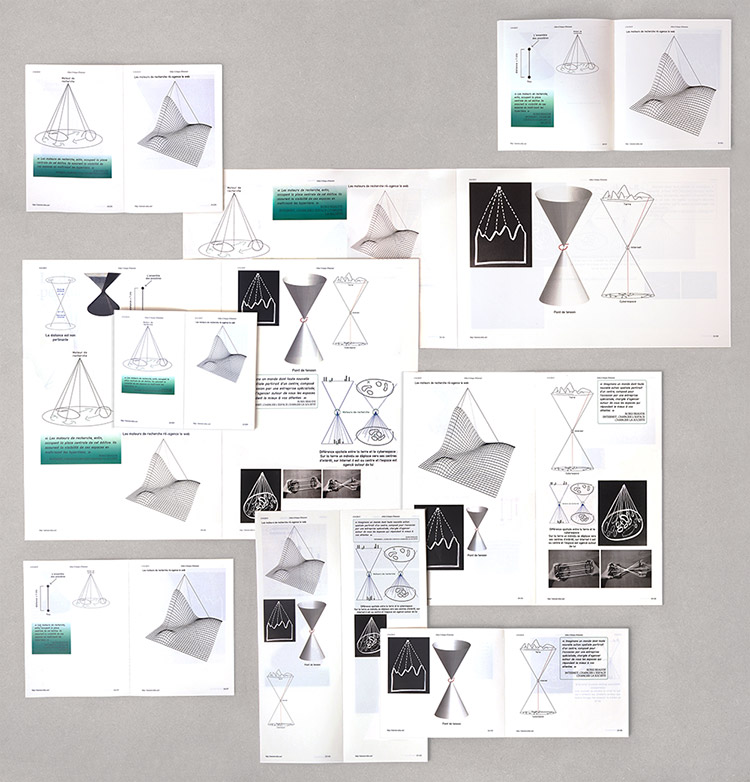

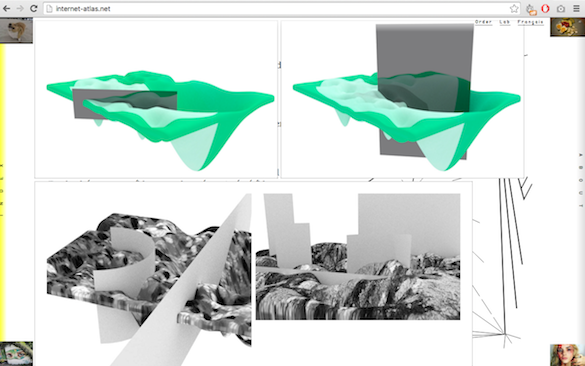

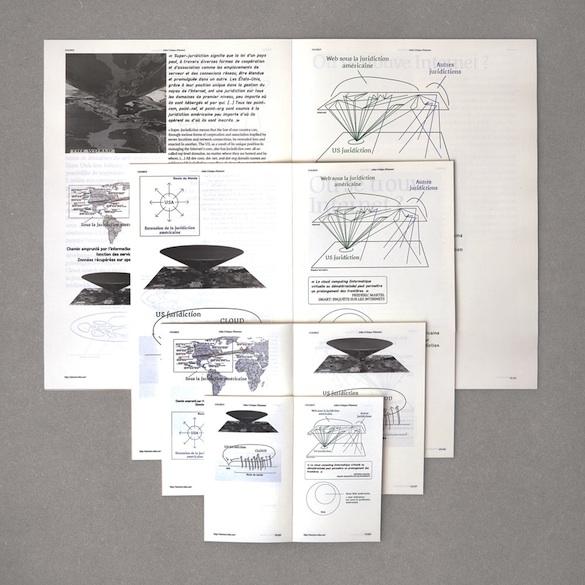

The Critical Atlas of the Internet, Louise Drulhe’s latest project, is a virtual and physical exploration of the Internet space. The implications of our physical actions in ‘real-time’ are not only timeless in ‘cyberspace’, but also constitute the making of an obscure Internet architecture every time we browse the web. The Atlas itself is an enveloping notebook of Drulhe’s discerning methodology in desiring to represent the geography and architecture of the ‘unseen’ Internet territory. Initially, a graphic designer, Drulhe’s practice has meticulously evolved into including cyber-spatial analysis. She yearns to understand the sociological, political and economical issues that appear online or are exasperated by an online presence – ‘a territory we spend time in without knowing its shape’. The Critical Atlas of the Internet, by being parted between fifteen different hypotheses, sheds light on matters such as the monopolisation of non-physical spaces, the possibility of encumbered networks and the potential forms of the Internet.

I had the pleasure of interviewing Drulhe, where she clarified certain distinctive matters that arise from reading or looking at the virtual form of the Atlas online.

CS: In 2014, Google measured 200TB of data that they claim to be just an estimated 0.004% of the total vastness of the Internet. Initially, the Atlas perceives the Internet through many geometric shapes such as cones and spheres. Is this your approach to establishing that the Internet is an infinite space of shared connections and motion? If this is the case, do you believe it is immeasurable?

LD: I will probably get back to you with a better answer to this question in a few months… I am starting an art residency in Paris at La Paillasse, and I will study the question: “can we measure Internet?”. I am curious to see the best way to represent the Internet: to count the data or to measure the borders. I haven’t started this research yet, but I will look for the best unit of measure to calculate the dimensions of Internet territory: meters? Litres? Percentages? Data traffic? I wonder how to define the “size” of a website. If we look at Google.com, it’s only one webpage, so does this mean that Google is smaller than a regular shopping website that might have thousands of pages?

With the fourth hypothesis of the Atlas, “The Geographic Relief of the Internet”, I tried to represent the «size» of Internet platforms. Their size is actually based on the concentration of the activities they host. The Internet giants try to saturate and incorporate as much territory as possible. Google (now called Alphabet) possesses Chrome, Gmail, Android, Google +, YouTube, Blogger, Google Map / Earth / Street View, Cloud, Nest, and Google X… to cite a few. Internet giants are almost raging an online war to monopolize most Internet territory. I think the next virgin land to conquer is the Internet of Things. The map of this 4th hypothesis is based on a ranking by Alexa’s Top 500 Global Sites. What I would like to do next is to measure this representation.

CS: Extrapolating from your claim that the Internet is a single point at the centre of the globe, what would the repercussions if that space were to be encumbered? Can a network not be encumbered?

LD: It’s true. A reticular space cannot be encumbered, I guess. Facebook.com, for instance, is getting more and more popular, but the site works perfectly; you don’t feel crowded situations on Facebook. If Facebook were a physical public square and 1 billion people met there one day, the situation would be really problematic. On Facebook, you never see the crowd.

In the Atlas, I quote Boris Beaude on this idea “The growth of reticular networks, unlike that of cities, increases their interaction potential without boosting their internal distances. Regardless of the network size, the distance between its respective parts is potentially non-existent. Facebook can host 800 million people without affecting its interaction capacity.”[1] This is what he calls “reticular coalescence”.

[1] Boris Beaude, Internet : “Changer l’espace, changer la société“. 2012.

CS: You build your thesis on the hypothesis that Internet space does not require distance; each component is of equal distance to the other. Otherwise, one click away. Whilst this grants no special status to any person’s ‘search’ to being more important or unimportant, aren’t these ‘search results’ always altered depending on the search engine? For example, untracked browsers such as Tor or extensions on Chrome such as ‘Hola’ have the capability to displace a user from their current location and thus materialise a different order by which results appear to us.

LD: I wrote that the search engines “control Internet architecture” and “distribute the space”. Because almost everyone uses Google, we can assume that Google is the one that controls Internet space so if you use another search engine, like “DuckDuckGo”, you will access the web through a different architecture. But “Tor” and “Hola” are not search engines. “Tor” is a network that enables anonymous communication, and “Hola” is a VPN.

By using a VPN, you can bypass censorship. By changing your localisation, the VPN will give you access to another web. There are as many Internets as there are legislations. This idea is represented in the hypothesis, “A Global Object Projected at the Local Level”. The Internet is global, but we use a national projection of the global network. If you are in China, with a VPN, you can browse the Romanian web and access websites censored by the Chinese government. VPNs also enable anonymity, but that’s another aspect of it.

CS: Another one of your hypotheses places us (the users) at the Internet’s centre, constructing the space around us as we move through it. Indeed, the Internet meets our individual needs. Would you, therefore, account for it more as a product – the world’s only flawless consumer good?

LD: Here, I would like to draw your attention to another aspect of my research. If we look at the Internet as a consumer good, it’s probably the first that actually turned consumers into products! In rephrasing one of Mike Edgan’s statements, Jason Fitzpatrick says, “If you are not paying for it, you’re not the customer; you’re the product being sold”. The personal data that are generated through users’ browsing are the new “petrol” of the oncoming economy. And in this particular economy, we won’t be the consumer anymore!

CS: In early forms of the Internet, ‘cyberspaces’ were decentralised. Now, as the Atlas conveys, data is concentrated within the hands of a few ‘heavy players’, illustrated as ‘network nodes’ of various weights burying themselves within the Internet’s surface. Since most of the ‘network nodes’ come from the west, would you consider the Internet to possess a particular Westphalian sovereignty?

LD: The centre of gravity of the Internet is clearly the west, but not, in my opinion, the west as a whole. The US has a dominant position for multiple reasons that I detailed in the Atlas. The Internet’s centre of gravity is defined as “the weight, concentrated solely at one focal point, instead of being distributed over several different points”, a focal point which is undeniably Silicon Valley.

CS: I’d like to ask you about the visual representation of your online Atlas. In particular, about the rigid protrusions of space, you used to convey the ‘splinternet’ and the humorous intrusions of Hilary Clinton and Bernie Sanders, among other seemingly unplanned objects such as fried eggs. Could you comment?

LD: We often imagine the Internet as a single Cloud and a unified territory, but this is wrong. Some multiple limits or frontiers exist online. Some of them are really clear, like the Great Firewall of China: the wall of censorship that divides the Chinese Internet from the rest of the Internet. Another obvious frontier is the limit between the deep web and the surface web. But the frontiers that interested me most were the ones that nobody seemed to pay attention to. The limits are defined by private networks, such as Facebook. People with a Facebook profile never see the frontier because there are always logged in. But when you do not have the password, Facebook is closed, even if some pages are left open to attract you. Their goal is to make you join the private network.

CS: And the unsystematic quirks?

LD: Each time the website loads, the images are automatically taken from the emblematic forum “Reddit”, defined as « the front page of the Internet ». Those images work as timestamps in the Atlas; you can find them at the 4 corners of the website and on the books. The Internet is a perpetually changing space, constantly evolving. It was important for me to bring a timestamp to my Atlas. In addition, these images are symbols of the Internet culture; the Internet meme: viral images spreading through the web and overflowing onto my Atlas.

CS: I’d like to address your citing of Introduction: Rhizome by Guattari and Deleuze. They claim that a rhizome can be connected to anything other and must be’ and therefore does not follow the same arborescent structure of a book or tree. However, as mentioned before, there are arborescent nodes within the Internet itself – the ‘heavy players’. Do you believe this may distract multiplicity or enhance the creation of territories within the Internet? Would you also support that in the case of a rupture, where a rhizome breaks or one of the arborescent nodes fall apart, another node responds to replace as if it was always as such?

LD: Yes, that’s a good comparison. I believe that the heavy players saturate and erode Internet space. This idea is supported by the fact that each company creates a personalized arborescence that is really difficult to connect to by developing its own patterns or ecosystems, like the arborescence of a tree. In this idea, they are breaking with the original shape of the network and its interoperability.

About the rupture, actually, I am not sure. If a node disappears on the network, another node will not necessarily be replaced. If a web page goes offline and at the same time a Facebook page has just been created, the new node (from Facebook) does not take its place. The new node is actually created within the Facebook network. And to refer to my hypothesis about the geographic relief of the Internet, the node opens on the slope of a dominant gap.

CS: As a final point, there’s a particular passage from Baudrillard’s Simulacra and Simulation which I find can be quite relative when considering the structure of the Internet:

“Abstraction today is no longer that of the map, the double, the mirror or the concept. Simulation is no longer that of a territory, a referential being or a substance. It is the generation by models of a real without origin or reality: a hyperreal. The territory no longer precedes the map nor survives it. Henceforth, it is the map that precedes the territory – the precession of simulacra – it is the map that engenders the territory. If we were to revive the fable today, it would be the territory whose shreds are slowly rotting across the map.”

How would you interpret this if we took into consideration Internet territories?

LD: Most people do not consider the Internet as a territory. This idea of cyberspace is a bit old-fashioned. But, I think it is still pertinent today to study the Internet as a real space.

The way we access representations of the Earth today is really magical. Google provides easy access to an extremely precise representation of the Earth through satellite images and maps… But for the territory of the Internet, it’s the opposite. Even if there are a few maps of the Internet, there are no basic tools to map the web. The territory still precedes the map. I would love to see what a Google street view of the Internet looks like!

Venue: The Photographers’ Gallery, London

Links: http://thephotographersgallery.org.uk/furtherfield-in-residence

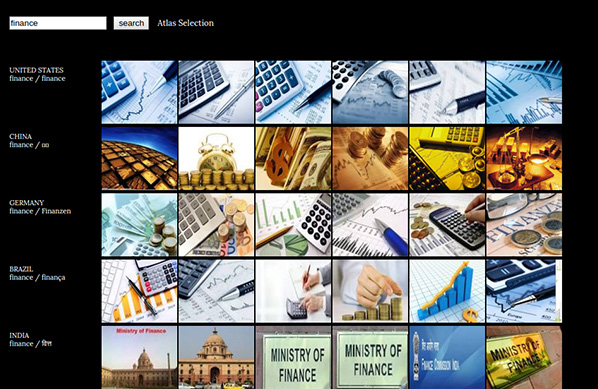

What do we find when we search our minds and the web for images of money and finance?

Coins and banknotes, trading floors with angry men shouting into phones, skyscrapers and stock charts.

The financial sector remains alienating and opaque to many people. We often struggle to think about how it works and how money moves. Making the invisible world of global finance visible and accessible is an urgent task and there are now many projects that are attempting to do just that.

Join us at The Photographers’ Gallery to build the ‘Activist Bloomberg terminal’ and to contribute to a mood board of future money.

Get involved in a weekend of image play, jargon-busting discussion, hacking and hands-on-exercises, to find out how we might unveil the financial sector. Together we will get involved with activities from open data mapping and visualisation, photography to computer games and digital art installation pieces to explore how money might be accurately represented in an era of digital payment via offshore tax havens.

This is part of Furtherfield’s Art Data Money programme of art shows labs and debates to build a commons for arts in the network age.

The Bloomberg Terminal is an expensive system that major banks use to get raw data and financial information. The Terminal is out of reach to most ordinary people, but can we create an open-source and open-access alternative Bloomberg to collect, distribute and visualise critical data on high finance? Let’s try!

Saturday 10.30 – 11.30: Brett Scott provides a recap of the first lab*

Open to all, an excellent introduction to the weekend activities.

Saturday 11.30 – 18:00 & Sunday 11:00 – 13:00: Discussions, guided group research, exercises and hands-on activities to familiarise yourself with finance and to build an ‘activist Bloomberg terminal’.

+ Read more about the first lab ‘Building the Activist Bloomberg to demystify High Finance’

What do we find when we search our minds (or the web) for images of money and finance?

And does it matter if we don’t like what we find? We think it does. We assert that money is an emotional, irrational and mysterious medium of networked trust and that the more we can reclaim its images and associations for communal play and circulation the more likely we are to shape it to our interests. That’s why we are building a new mood board for future money.

Saturday 12:00 – 13:00: introduction to the image of money

Talk – Brett Scott (LSFA) introduces the topic with a broad sweep history of money from the primordial swamp to High Frequency Trading

Saturday 13.00 – 17.00: Money mood board workshop

Participants are invited to drop in and take a series of challenges to make, remix and reappropriate photographs – going out onto the streets, searching, interpreting and tagging photographs from some great digital archives and the World Wide Web to create a new image bank for money past, present and future – online and on the walls of The Photographers Gallery

Sunday 11.00 – 13.00: Money mood board workshop continued

Sunday 14.00 – 17.00: Sunday Workshop – Money Masks

Furtherfield take over our regular drop-in workshop for all ages. Visitors are invited to imagine the main players in the future of money and finance: mysterious, glamorous, fierce or ethereal, human or machine. Download, print, collage and assemble masks for a carnival of characters in the future of money.

Reclaim money for the good of us all, and have fun doing it, join us for a weekend.

All events are included with exhibition day pass charge, no booking necessary

Daniel Rourke: At Furtherfield on November 22nd 2014 you launched a Beta version of a networked project, 6PM Your Local Time, in collaboration with Fabio Paris, Abandon Normal Devices and Gummy Industries. #6PMYLT uses twitter hashtags as a nexus for distributed art happenings. Could you tell us more about the impetus behind the project?

Domenico Quaranta: In September 2012, the Link Art Center launched the Link Point in Brescia: a small project space where, for almost two years, we presented installation projects by local and international artists. The Link Point was, since the beginning, a “dual site”: a space where to invite our local audience, but also a set for photographic documentation meant to be distributed online to a global audience. Fabio Paris’ long experience with his commercial gallery – that used the same space for more than 10 years, persuaded us that this was what we had to offer to the artists invited. So, the space was reduced to a small cube, white from floor to ceiling, with neon lights and a big logo (a kind of analogue watermark) on the back door.

Thinking about this project, and the strong presence of the Link Point logo in all the documentation, we realized that the Link Point was actually not bound to that space: as an abstract, highly formalized space, it could actually be everywhere. Take a white cube and place the Link Point logo in it, and that’s the Link Point.

This realization brought us, on the one hand, to close the space in Brescia and to turn the Link Point into a nomad, erratic project, that can resurrect from time to time in other places; and, on the other hand, to conceive 6PM Your Local Time. The idea was simple: if exhibition spaces are all more or less similar; if online documentation has become so important to communicate art events to a wider audience, and if people started perceiving it as not different from primary experience, why not set up an exhibition that takes place in different locations, kept together only by documentation and by the use of the same logo? All the rest came right after, as a natural development from this starting point (and as an adaptation of this idea to reality).

Of course, this is a statement as well as a provocation: watching the documentation of the UK Beta Test you can easily realize that exhibition spaces are NOT more or less the same; that attending or participating in an event is different from watching pictures on a screen; that some artworks work well in pictures but many need to be experiences. We want to stress the value of networking and of giving prominence to your network rather than to your individual identity; but if the project would work as a reminder that reality is still different from media representation, it would be successful anyway.

Daniel Rourke: There is something of Hakim Bey’s Temporary Autonomous Zones in your proposal. The idea that geographic, economic and/or political boundaries need no longer define the limits of social collective action. We can criticise Bey’s 1991 text now, because in retrospect the Internet and its constitutive protocols have themselves become a breeding ground for corporate and political concerns, even as technology has allowed ever more distributed methods of connectivity. You foreground network identity over individual identity in the 6PM YLT vision, yet the distinction between the individuals that create a network and the corporate hierarchies that make that networking possible are less clear. I am of course gesturing towards the use of Twitter as the principal platform of the project, a question that Ruth Catlow brought up at the launch. Do you still believe that TAZs are possible in our hyper-connected, hyper-corporate world?

Domenico Quaranta: In its first, raw conceptualization, 6PM YLT had to come with its own smartphone app, that had to be used both to participate in the project and to access the gallery. The decision to aggregate content published on different social platforms came from the realization that people already had the production and distribution tools required to participate in the action, and were already familiar with some gestures: take a photo, apply a filter, add an hashtag, etc. Of course, we could invite participants and audiences to use some specific, open source social network of our choice, but we prefer to tell them: just use the fucking platform of your choice. We want to facilitate and expand participation, not to reduce it; and we are not interested in adding another layer to the project. 6PM YLT is not a TAZ, it’s just a social game that wants to raise some awareness about the importance of documentation, the power of networks, the public availability of what we do with our phones. And it’s a parasitic tool that, as anything else happening online, implies an entire set of corporate frameworks in order to exist: social networks, browsers, operative systems, internet providers, server farms etc.

That said, yes, I think TAZs are still possible. The model of TAZ has been designed for an hyper-connected, hyper-corporate world; they are temporary and nomadic; they exist in interstices for a short time. But I agree that believing in them is mostly an act of faith.

Daniel Rourke: The beta-tested, final iteration of 6pm YLT will be launched in the summer of 2015. How will you be rolling out the project in the forthcoming months? How can people get involved?

Domenico Quaranta: 6PM Your Local Time has been conceived as an opportunity, for the organizing subject, to bring to visibility its network of relationships and to improve it. It’s not an exhibition with a topic, but a social network turned visible. To put it simply: our identity is defined not just by what we do, but also by the people we hang out with. After organizing 6PM Your Local Time Europe, the Link Art Center would like to take a step back and to offer the platform to other organizing subjects, to allow them to show off their network as well.

So, what we are doing now is preparing a long list of institutions, galleries and artists we made love with in the past or we’d like to make love with in the future, and inviting them to participate in the project. We won’t launch an open call, but we already made the event public saying that if anyone is interested to participate, they are allowed to submit a proposal. We won’t accept anybody, but we would be happy to get in touch with people we didn’t know.

After finalizing the list of participants, we will work on all the organizational stuff, basically informing them about the basic rules of the game, gathering information about the events, answering questions, etc.

On the other hand, we have of course to work on the presentation. While every participant presents an event of her choice, the organizer of a 6PM Your Local Time event has to present to its local audience the platform event, as an ongoing installation / performance. We are from Brescia, Italy, and that’s where we will make our presentation. We made an agreement with MusicalZOO, a local festival of art and electronic music, in order to co-produce the presentation and have access to their audience. This is what determined the date of the event in the first place. Since the festival takes place outdoor during the summer, we are working with them on designing a temporary office where we can coordinate the event, stay in touch with the participants, discuss with the audience, and a video installation in which the live stream of pics and videos will be displayed. Since we are expecting participants from Portugal to the Russian Federation, the event will start around 5 PM, and will follow the various opening events up to late night.

One potential reference for this kind of presentation may be those (amazing) telecommunication projects that took place in the Eighties: Robert Adrian’s The World in 24 Hours, organized at Ars Electronica in 1982; the Planetary Network set up in 1986 at the Venice Biennale; and even Nam June Paik’s satellite communication project Good Morning Mr Orwell (1984).

Daniel Rourke: Your exhibition Unoriginal Genius, featuring the work of 17 leading net and new media artists, was the last project to be hosted in the Carroll/Fletcher Project Space (closing November 22nd, 2014). Could you tell us more about the role you consider ‘genius’ plays in framing contemporary art practice?

Domenico Quaranta: The idea of genius still plays an important role in Western culture, and not just in the field of art. Whether we are talking about the Macintosh, Infinite Jest, a space trip or Nymphomaniac, we are always celebrating an individual genius, even if we perfectly know that there is a team and a concerted action behind each of these things. Every art world is grounded in the idea that there are gifted people who, provided specific conditions, can produce special things that are potentially relevant for anybody. This is not a problem in itself – what’s problematic are some corollaries to our traditional idea of genius – namely “originality” and “intellectual property”. The first claims that a good work of creation is new and doesn’t depend on previous work by others; the second claims that an original work belongs to the author.

In my opinion, creation never worked this way, and I’m totally unoriginal in saying this: hundreds of people, before and along to me, say that creating consists in taking chunks of available material and assembling them in ways that, in the best situation, allow us to take a small step forward from what came before. But in the meantime, entire legal systems have been built upon such bad beliefs; and what’s happening now is that, while on the one hand the digitalization of the means of production and dissemination allow us to look at this process with unprecedented clarity; on the other hand these regulations have evolved in such a way that they may eventually slow down or stop the regular evolution of culture, which is based on the exchange of ideas.

We – and creators in particular – have to fight against this situation. But Unoriginal Genius shouldn’t be read in such an activist way. It is just a small attempt to show how the process of creation works today, in the shared environment of a networked computer, and to bring this in front of a gallery audience.

Daniel Rourke: So much online material ‘created’ today is free-flowing and impossible to trace back to an original author, yet the tendency to attribute images, ideas or ‘works’ to an individual still persists – as it does in Unoriginal Genius. I wonder whether you consider some of the works in the show as more liberated from authorial constraints than others? That is, what are the works that appear to make themselves; floating and mutating regardless of particular human (artist) intentions?

Domenico Quaranta: Probably Museum of the Internet is the one that fits best to your description. Everybody can contribute anonymously to it by just dropping images on the webpage; the authors’ names are not available on the website, and there’s no link to their homepage. It’s so simple, so necessary and so pure that one may think that it always existed out there in some way or another. And in a way it did, because the history of the internet is full of projects that invite people to do more or less the same.

Daniel Rourke: 2014 was an exciting year for the recognition of digital art cultures, with the appointment of Dragan Espenschied as lead Digital Conservator at Rhizome, the second Paddles On! auction of digital works in London, with names like Hito Steyerl and Ryan Trecartin moving up ArtReview’s power list, and projects like Kenneth Goldsmith’s ‘Printing out the Internet’ highlighting the increasing ubiquity – and therefore arguable fragility – of web-based cultural aggregation. I wondered what you were looking forward to in 2015 – apart from 6PM YLT of course. Where would you like to see the digital/net/new media arts 12 months from now?

Domenico Quaranta: On the moon, of course!

Out of joke: I agree that 2014 has been a good year for the media arts community, as part of a general positive trend along the last few years. Other highlighs may include, in various order: the September 2013 issue of Artforum, on “Art and Media”, and the discussion sparked by Claire Bishop’s essay; Cory Arcangel discovering and restoring lost Andy Warhol’s digital files from floppy disks; Ben Fino-Radin becoming digital conservator at MoMA, New York; JODI winning the Prix Net Art; the Barbican doing a show on the Digital Revolution with Google. Memes like post internet, post digital and the New Aesthetic had negative side effects, but they helped establishing digital culture in the mainstream contemporary art discourse, and bringing to prominence some artists formerly known as net artists. In 2015, the New Museum Triennial will be curated by Lauren Cornell and Ryan Trecartin, and DIS has been announced to be curator of the 9th Berlin Biennial in 2016.

All this looks promising, but one thing that I learned from the past is to be careful with optimistic judgements. The XXI century started with a show called 010101. Art in Technological Times, organized by SFMoMA. The same year, net art entered the Venice Biennale, the Whitney organized Bitstreams and Data Dynamics, the Tate Art and Money Online. Later on, the internet was announced dead, and it took years for the media art community to get some prominence in the art discourse again. The situation now is very different, a lot has been done at all levels (art market, institutions, criticism), and the interest in digital culture and technologies is not (only) the result of the hype and of big money flushed by corporations unto museums. But still, where we really are? The first Paddles On! Auction belongs to history because it helped selling the first website ever on auction; the second one mainly sold digital and analogue paintings. Digital Revolution was welcomed by sentences like: “No one could fault the advances in technology on display, but the art that has emerged out of that technology? Well, on this showing, too much of it seems gimmicky, weak and overly concerned with spectacle rather than meaning, or making a comment on our culture.” (The Telegraph) The upcoming New Museum Triennial will include artists like Ed Atkins, Aleksandra Domanovic, Oliver Laric, K-HOLE, Steve Roggenbuck, but Lauren and Ryan did their best to avoid partisanship. There’s no criticism in this statement, actually I would have done exactly the same, and I’m sure it will be an amazing show that I can’t wait to see. Just, we don’t have to expect too much from this show in terms of “digital art recognition”. So, to put it short: I’m sure digital art and culture is slowly changing the arts, and that this revolution will be dramatic; but it won’t take place in 2015 🙂

An International Online Symposium on Innovation in Networked Research, Artistic Production and Teaching in the Arts

Opening Reception: Tuesday, March 31, 11:00 AM – 1:00 PM BST (British Summer Time)

For online access login to Adobe Connect as a Guest: http://ntu.adobeconnect.com/symposium2015

11:00 AM – 11:30 AM (BST)

Welcoming Remarks from Singapore: Symposium co-chairs, Randall Packer & Vibeke Sorensen

Welcoming Remarks from London: Furtherfield co-founders & co-directors, Ruth Catlow & Marc Garrett

11:30 AM – 12:30 PM (BST)

@ Home With Furtherfield: Join Furtherfield co-directors Ruth Catlow & Marc Garrett for an intimate telematic gathering of Internet artist interviews & conversation with: Nick Briz, Joseph Chiocchi, Helen Varley Jamieson, Maxime Marion, Juergen Trautwein, Joana Moll.

12:30 PM – 1:00 PM (BST)

Live Webcam Cyberformance: we r now[here] is a cyberformance about nowhere and somewhere: the “nowhere” of the Internet becomes “now” and “here” through our virtual presence. Created by Helen Varley Jamieson and performed by NTU students.

For more information visit the Art of the Networked Practice | Online Symposium website.

Contact: gabrielle@andfestival.org.uk

Hashtag: #6pmuk

Participants: TBC

VISITING INFORMATION

DOWNLOAD PRESS RELEASE

6PM YLT is a networked, distributed, one night contemporary art event, which takes place simultaneously in different locations, coordinated from one central venue, and documented online via a web application.

Furtherfield is hosting the first UK event, chosen for its history of critical engagement with networked culture.

At 5.30 pm, Domenico Quaranta and Fabio Paris from Link Art Center will talk through their ambitions and inspiration for the project. For the duration of the event, participating venues and their audiences across the UK will be testing the platform by sharing documentation images and videos of their events under the same hashtag, #6pmuk. The audience at Furtherfield will be able to enjoy the live feed from all the locations involved, and to discuss the project with us.

Artists, technologists, network thinkers and makers are invited to join us to learn more about the conceptual framework for 6PM YLT and talk through how it can evolve, in anticipation of its European launch in July. Food and drinks will be available!

6PMYLT is a format conceived by the Link Art Center and developed in collaboration with Abandon Normal Devices (AND) and Gummy Industries. On 22 July 6 PM YOUR LOCAL TIME launches across Europe.

6 PM YOUR LOCAL TIME (6PM YLT) is a networked, distributed, one night contemporary art event taking place simultaneously in different locations, coordinated from one central venue and documented online via a web application. The locations (institutions, non-profit spaces, commercial galleries, artist’s studios) will address their local audience and, through the dedicated web platform, a global audience. While visiting your local 6PM YLT event(s) will allow you to experience a single portion first hand, the only way to get the whole picture will be to access its online documentation: all exhibits will be documented and shared in real time by organizers and audience on the dedicated web platform, thanks to a web application aggregating content from different social platforms.

The lead partner will coordinate the event from one central venue, and will put on display the event itself, screening the live feed from all the locations involved, and eventually making additional documentation available in different ways, ie. arranging video conferences with specific venues, or printing out images in real time and displaying them as a wall installation.

After the launch event, 6PMYLT will become an open format available for anyone to utilise. The lead partners will maintain the platform and support the coordination of events all around the world.

Today, art is mostly experienced through its documentation. Even if globalization made it easier and cheaper to organize exhibitions, ship artworks, invite artists and move audiences to any part of the world, the excess of cultural activity all around the world makes it impossible to be everywhere at the same time. Bits are still faster and cheaper than atoms, and we can enjoy them more comfortably on different devices. The border between first hand and second hand experience, reality and media documentation becomes increasingly blurred, with a profound impact on the way art is produced and documented.

Almost every art-addict is now using social networks like Instagram, Twitter and Facebook to take photographs during art exhibitions and to share them with their contacts. The pictures already have some meta-data that we could use to trace them and to collect them: #hashtags, captions, geographical data, publishing date. By suggesting the use of a given #hashtag to all the organizers and audience participants, we can collect and show all this documentation on a dedicated web platform. Our software will automatically collect all the pictures, tweets, and public Facebook produced about the 6PM YLT event, and will show them in a single gallery.

6PMYLT is a format conceived by the Link Art Center and developed in collaboration with Abandon Normal Devices (AND) and Gummy Industries.

The Link Center for the Arts of the Information Age (Link Art Center) is a no-profit organization promoting artistic research with new technologies and critical reflections on the core issues of the information age: it organizes exhibitions, events, conferences and workshops, publishes books, forges partnerships with private and institutional partners and networks with similar organizations worldwide. More info: www.linkartcenter.eu

Abandon Normal Devices (AND) presents world-class artists at the frontiers of art, digital culture and new cinema. A UK based organisation it is a catalyst for new approaches to art-making and digital invention, commissioning public realm works, exhibitions, research projects and a roaming biennial festival. AND has commissioned work from Carolee Schneeman, Krystoph Wodischko, Gillian Wearing, Phil Collins, Rafael Lozano Hemmer and the Yes Men (to name but a few). More info: www.andfestival.org.uk/

Gummy Industries is an online communication and marketing agency based in Brescia, Italy. Their work ranges from consultancy to design and (web) development. They usually work with medium business and large companies, with a strong focus on the fashion industry. More info: http://gummyindustries.com/

Furtherfield was founded by artists Ruth Catlow and Marc Garrett in 1997 and is been sustained by the work of its community; specialist and amateur artists, activists, thinkers, and technologists, who, together cultivate open, critical contexts for making and thinking. Furtherfield is now a dynamic, creative and social nerve centre where upwards of 26,000 contributors worldwide have built a visionary culture around co-creation – swapping and sharing code, music, images, video and ideas. More info: www.furtherfield.org.

Concept: Fabio Paris

Production: Link Art Center, Brescia, IT

Co-production: Abandon Normal Devices, Manchester, UK

Website and software development: Gummy Industries, Brescia, IT

Funded by: Creative Europe; Art Council England

6PM YOUR LOCAL TIME is realized in the framework of Masters & Servers, a joint project by Aksioma (SI), Drugo more (HR), Abandon Normal Devices (UK), Link Art Center (IT) and d-i-n-a / The Influencers (ES) that was recently awarded with a Creative Europe 2014 – 2020 grant. For 24 months from now, Masters & Servers will explore networked culture in the post-digital age.

Furtherfield presents DIGITAL ZOO: Life from the world wild web, a touring exhibition that invites audiences to explore and marvel at new patterns of human and digital behaviours in the network age.

Featuring Andy Deck, Mary Flanagan, Genetic Moo, Liz Sterry, Thomson & Craighead, Pete Gomes, and a new interactive mobile artwork commission by Transnational Temps.

DIGITAL ZOO features experimental software, interactive videos, installations, workshops, networked and mobile media created by internationally recognised artists inspired to explore the ways in which our lives are being shaped by digital technologies, and challenge the concept that digital art is only accessible in galleries or online.

Since 2008 artist group Genetic Moo have been developing a series of interactive video installations using choreographed video clips that respond in a variety of life-like ways to user motion and touch. With Animacules they take inspiration from the 19th century sea life illustrations of Ernst Haeckel and the work of the 17th century Dutch scientist Antonie van Leeuwenhoek to create a dark sea of wiggling, luminescent creatures that gorge on torch light.

Internationally renowned artist duo Thomson & Craighead create a new site-specific installation especially for the DIGITAL ZOO tour. A wall of propaganda style posters of the Tweets and other status updates drawn from people in the local area of the tour venues, offers a poetic snapshot of the invisible conversations taking place, “the idle mutterings of ourselves to ourselves as a form of concrete poetry.” The work is based on the artists’ London Wall series shown at the Museum of London (2010), Furtherfield Gallery (2012) and Carroll/Fletcher (2013).

Liz Sterry is an artist fascinated with the way people use the Internet to express themselves. In Kay’s Blog she presents an exact physical replica of a young woman’s bedroom, recreated through information, images and notes about her daily life that the real Kay posted on her public blog. With social media often used as a platform for self-expression and performance, the work questions how much of ourselves we share online with strangers without even realising it.

With his novel use of Twitter, US artist Andy Deck savours the wildness of everyday language with people around the world, inspired by the wealth of nature-related sayings passed down over centuries. He invites audiences to help him build a bestiary of animal idioms using social media and an interactive installation.

Experimental filmmaker Pete Gomes invited residents in Sunderland with no acting experience to participate in a 45 minute long acting session. Each participant was directed to perform on camera for a single five-minute take. Screened as a series, Cycle of Purposes questions reality and artifice by exploring how thoughts and feelings are acted, amplified, exaggerated and stylised every day in response to different people and places.

Mary Flanagan travels overland and undersea, in virtual worlds built and inhabited by other virtual beings. [borders] is a video documentation of her walks in beautiful and hypnotic landscapes that expose the boundaries of the virtual world by testing its edges. Her walks are inspired by Thoreau, the great American nature writer and walker, who, avoiding highways, chose instead to wander in order to understand the spiritual possibilities of the landscape.

Mall of the Wild by Transnational Temps is a new commission created especially for Digital Zoo. Players help the famous artist Magritte to find fake wildlife in the shopping centre. Equipped with a store map and a smart phone app, they have limited time to find a number of representations of wild animals visible in the products of the shopping centre. They map rare species and share their wildlife documentary photos in the online “Ceci n’est pas…” collection via social networks.

In creating DIGITAL ZOO, Furtherfield believe that digital networks and social media offer the potential for a more open relationship between artists and audiences, changing the life of an artwork in the world, and the ways in which people encounter it, and sometimes collaborate in its creation.

Personal information is exchanged with increasing frequency, and daily lives are becoming ever more public, as if in a public zoo. People are both animals and visitors; hunters, trackers, observers, naturalists and zookeepers; and educators and pundits. The longer-term social effects of this collective public performance are awaited…

The exhibition was accompanied by a series of creative workshops inspired by Crow_Sourcing for children aged 6-11 years old.

Curated and produced by Furtherfield in collaboration with Culture Code and Land Securities.

Digital Zoo is supported by Arts Council England through the Strategic Touring programme.

Crow_Sourcing by Andy Deck was made possible with funding from the Jerome Foundation, and was a 2012 Commission of New Radio and Performing Arts, Inc. for its Turbulence website.

Featured image: Thomson and Craighead, Here (2013)

Visiting Jon Thomson and Alison Craighead’s survey exhibition, Never Odd Or Even, currently on show at Carroll / Fletcher Gallery, I found myself confronted with an enigma. How to assemble a single vision of a body of work, impelled only by the dislocated narratives it offers me? ‘Archaeology’ is derived from the Greek word, arche, meaning ‘beginning’ or ‘origin’. The principle that makes a thing possible, but which in itself may remain elusive, unquantifiable, or utterly impervious to analysis. And so it is we search art for an origin, for an arising revelation, knowing full well that meaning is not something we can pin down. Believing, that the arche of a great work is always just about to take place.

In an essay written especially for the exhibition, David Auerbach foregrounds Thomson and Craighead’s work in the overlap between “the quotidian and the global” characteristic of our hyperconnected contemporary culture. Hinged on “the tantalising impossibility of seeing the entire world at once clearly and distinctly” [1] Never Odd Or Even is an exhibition whose origins are explicitly here and everywhere, both now and anywhen. The Time Machine in Alphabetical Order (2010), a video work projected at the heart of the show, offers a compelling example of this. Transposing the 1960 film (directed by George Pal) into the alphabetical order of each word spoken, narrative time is circumvented, allowing the viewer to revel instead in the logic of the database. The dramatic arcs of individual scenes are replaced by alphabetic frames. Short staccato repetitions of the word ‘a’ or ‘you’ drive the film onwards, and with each new word comes a chance for the database to rewind. Words with greater significance such as ‘laws’, ‘life’, ‘man’ or ‘Morlocks’ cause new clusters of meaning to blossom. Scenes taut with tension and activity under a ‘normal’ viewing feel quiet, slow and tedious next to the repetitive progressions of single words propelled through alphabetic time. In the alphabetic version of the film it is scenes with a heavier focus on dialogue that stand out as pure activity, recurring again and again as the 96 minute 55 second long algorithm has its way with the audience. Regular sites of meaning become backdrop structures, thrusting forward a logic inherent in language which has no apparent bearing on narrative content. The work is reminiscent of Christian Marclay’s The Clock, also produced in 2010. A 24 hour long collage of scenes from cinema in which ‘real time’ is represented or alluded to simultaneously on screen. But whereas The Clock’s emphasis on cinema as a formal history grounds the work in narrative sequence, Thomson and Craighead’s work insists that the ground is infinitely malleable and should be called into question.

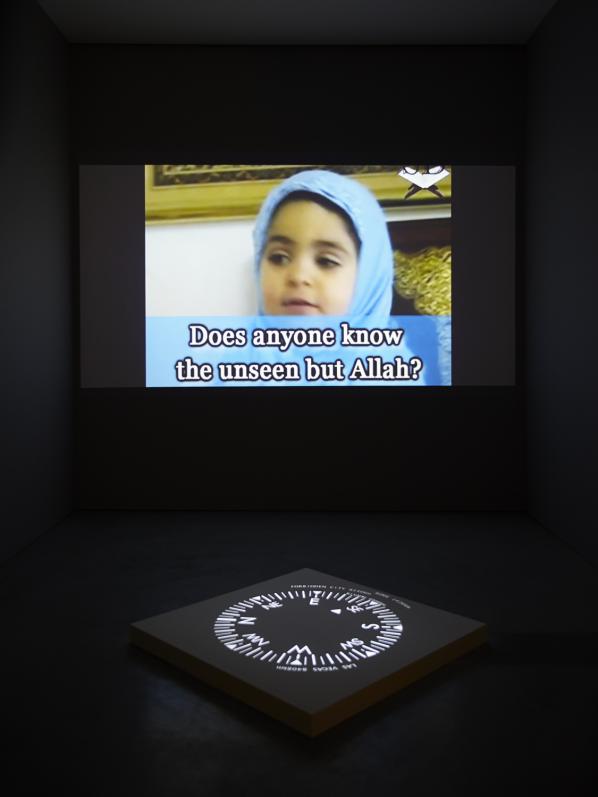

Another work, Belief (2012), depicts the human race as a vast interlinked, self-reflexive system. Its out-stretched nodes ending at webcams pointing to religious mediators, spiritual soliloquists and adamant materialists, all of them searching to define what it means to be in existence. Projected on the floor of the gallery alongside the video a compass points to the location each monologue and interview was filmed, spiralling wildly each time the footage dissolves. Each clip zooms out of a specific house, a town, a city and a continent to a blue Google Earth™ marble haloed by an opaque interface. Far from suggesting a utopian collectivity spawned by the Google machine, Belief once again highlights the mutable structures each of us formalise ourselves through. As David Auerbach suggests, the work intimates the possibility of seeing all human kind at once; a world where all beliefs are represented by the increasingly clever patterns wrought through information technology. Instead, culture, language and information technology are exposed as negligible variables in the human algorithm: the thing we share is that we all believe in something.

Never Odd Or Even features a series of works that play more explicitly with the internet, including London Wall W1W (2013), a regularly updated wall of tweets sent from within a mile of the gallery. This vision of the “quotidian” out of the “global” suffers once you realise that twitter monikers have been replaced with each tweeter’s real name. Far from rooting the ethereal tweets to ‘real’ people and their geographic vicinity the work paradoxically distances Thomson and Craighead from the very thing twitter already has in abundance: personality. In a most appropriate coincidence I found myself confronted with my own tweet, sent some weeks earlier from a nearby library. My moment of procrastination was now a heavily stylised, neutralised interjection into Carroll / Fletcher gallery. Set against a sea of thoughts about the death of Margaret Thatcher, how brilliant cannabis is, or what someone deserved for lunch I felt the opposite of integration in a work. In past instances of London Wall, including one at Furtherfield gallery, tweeters have been contacted directly, allowing them to visit their tweet in its new context. A gesture which as well as bringing to light the personal reality of twitter and tweeters no doubt created a further flux of geotagged internet traffic. Another work, shown in tandem with London Wall W1W, is More Songs of Innocence and of Experience (2012). Here the kitsch backdrop of karaoke is offered as a way to poetically engage with SPAM emails. But rather than invite me in the work felt sculptural, cold and imposing. Blowing carefully on the attached microphone evoked no response.

The perception and technical malleability of time is a central theme of the show. Both, Flipped Clock (2009), a digital wall clock reprogrammed to display alternate configurations of a liquid crystal display, and Trooper (1998), a single channel news report of a violent arrest, looped with increasing rapidity, uproot the viewer from a state of temporal nonchalance. A switch between time and synchronicity, between actual meaning and the human impetus for meaning, plays out in a multi-channel video work Several Interruptions (2009). A series of disparate videos, no doubt gleaned from YouTube, show people holding their breath underwater. Facial expressions blossom from calm to palpable terror as each series of underwater portraits are held in synchrony. As the divers all finally pull up for breath the sequence switches.

According to David Auerbach, and with echoes from Thomson and Craighead themselves, Never Odd Or Even offers a series of Oulipo inspired experiments, realised with constrained technical, rather than literary, techniques. For my own reading I was drawn to the figure of The Time Traveller, caused so splendidly to judder through time over and over again, whilst never having to repeat the self-same word twice. Mid-way through H.G.Wells’ original novel the protagonist stumbles into a crumbling museum. Sweeping the dust off abandoned relics he ponders his machine’s ability to hasten their decay. It is at this point that the Time Traveller has a revelation. The museum entombs the history of his own future: an ocean of artefacts whose potential to speak died with the civilisation that created them. [2] In Thomson and Craighead’s work the present moment we take for granted becomes malleable in the networks their artworks play with. That moment of arising, that archaeological instant is called into question, because like the Time Traveller, the narratives we tell ourselves are worth nothing if the past and the present arising from it are capable of swapping places. Thomson and Craighead’s work, like the digital present it converses with, begins now, and then again now, and then again now. The arche of our networked society erupting as the simulation of a present that has always already slipped into the past. Of course, as my meditation on The Time Traveller and archaeology suggests, this state of constant renewal is something that art as a form of communication has always been intimately intertwined with. What I was fascinated to read in the works of Never Odd Or Even was a suggestion that the kind of world we are invested in right now is one which, perhaps for the first time, begs us to simulate it anew.

DIWO (Do-It-With-Others): Origin, Art & Social Context, is an update on Furtherfield’s artistic and cultural practice of DIWO. In light of the emergence of DIWO in other fields of creative practices, and its ever growing popularity. We reconnect to the original reasons of why Furtherfield introduced and shared the concept of DIWO to the world in the first place.

We revisit early historical influences from 60s and 70s Mail Art, Fluxus, Situationism, Activism and D.I.Y culture; early adventures/projects with pirate radio, a mass networked email art, and (snail mail) mail art’, street art project by Furtherfield back in 1999; to what DIWO is now today, part of a more extensive, and networked grass roots movement around the world.

It also draws upon links to P2P (peer to peer) culture, the free and open source movement. Each of these cultural activities are seen as equal, peer relations, and re-hacks an intuitive space away from traditional hegemonies and their established hierarchies.

It re-emphasize it’s core motives, as a critique against mainstream media and the traditional art establishment’s control over our art history and contemporary art imaginations. It challenges the non-critical nature of artists’ complicit desire in conforming to celebrity status and fitting into stereotypical behaviours informed by hegemony, and cultural dominance. Furthefield’s intention for DIWO has always been a about individual and collective emancipation, and this story is about what this means now…

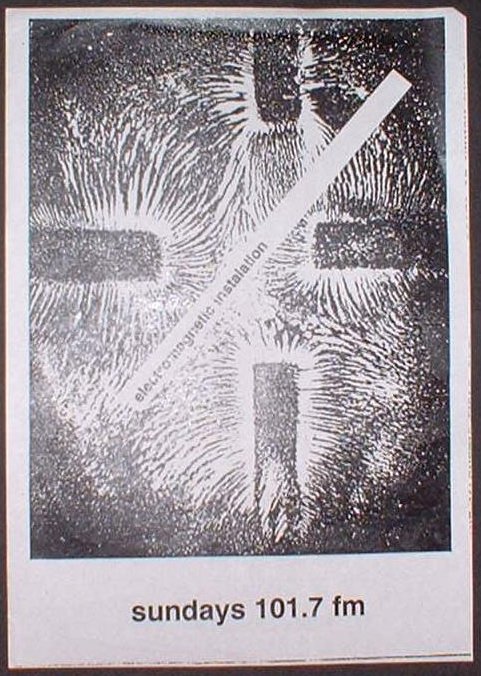

Before we jump into Furtherfield’s first DIWO project it’s worth mentioning an earlier historical reference to Bristol city (UK) and pirate radio. I, and a dedicated group of individuals were interested in finding alternative avenues for community and collective expression. We set up various pirate radio stations in Bristol, the longest running was ‘Electro Magnetic Installation (EMI)’ pirate radio station, which ran for over 18 months, broadcasting to greater Bristol every weekend ending in 1991. We changed our location for each broadcast and disseminated disinformation to confuse the authorities. We used a home built 20 Watt stereo FM transmitter and antenna. All submitted material was provided on audio tape for broadcast, the quality or quantity was not edited and everyone interested had their sound art, cut up mixes, music and words heard by many. We had to close down after a while due to surveillance stress. We did re-emerge with other pirate radio broadcasts briefly, under various different names. An even earlier one, which we took over for a while was called ‘savage but tender’ in 1989.

Bristol in the late 80s and early 90s was a dynamic and exciting place to be. Especially if one was creative and also interested in alternative ways of thinking and living. Independent culture was thriving. It was back in the 70s when Bristol’s radical spirit of creative and political autonomy was first forged. Post punk bands such as the Pop Group, Rip Rig & Panic, spread their own influential ethos of being creative and activist as a way of life. Advocating everyday people could be different, be independent thinkers and question the validity of the established norm. This flexible blueprint of being socially conscious in an imaginative way influenced a huge mixture of genres for years to come. Breaking down the borders between the audience and the musicians playing was a legacy handed on down from punk. This includes building your own record label, setting up your own pirate radio station, self publishing and other ventures.

Furtherfield’s first collective (yet unofficial) DIWO experience was at the Watermans Art Centre, London in 1999. We were asked to present a project which reflected the free and liberated spirit of our networked on-line community and its creative culture. The name of the project was called “Pasteups@Watermans Art Centre”, not DIWO. It had all the features of DIWO, such as using email as art, and the traditional postal services (snail mail) as part of its distribtion process. From all over the world people were invited to send images and texts which were then enlarged into a mass of photocopied posters.

On Sunday 10th October 1999 all the hoardings and wall spaces in the streets around the Watermans Art Centre were blitzed with Pasteups. There was no selection of what should be taken out or left in, everything was shown. They were put up by the Furtherfield crew and who ever wished to help out. Some of those whom took part were also local to the area. The people working in the centre reacted as if they were being over taken from a dark external force, and the passing public were expressing a mixture of emotions – enjoyment, surprise, interest, confusion, distaste and annoyance. It challenged the ideal of art having to be a rigid divide and rule of amateur vs professional, using the Internet and the physicalness of the Watermans Art Centre’s building, inside and outside. The streets were used as a shared canvas to fill our collective, imaginative expressions at that time.

“”… the role of the artist today has to be to push back at existing infrastructures, claim agency and share the tools with others to reclaim, shape and hack these contexts in which culture is created.” [1] (Catlow 2010)

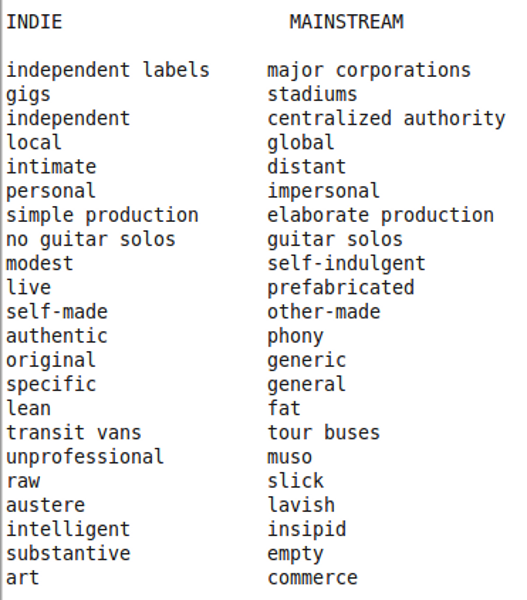

In her study ‘Empire of Dirt: The Aesthetics and Rituals of British Indie Music (Music Culture)’, Dr. Wendy Fonarow [2] investigated the UK’s indie music scene and its culture from the early 1990s to present. Below Fonarow presents the differences between mainstream and independent music culture. Contrasts are mapped out in Lévi-Straussian fashion: