While archaeology has often understood cultures through excavations of hoards and coins, what will today’s digital currencies tell future archaeologists about the way we live and trade?

This co-commission with NEoN Digital Arts Festival forms part of Furtherfield’s ongoing investigations into the politics of the blockchain, smart contracts, and cryptocurrency systems like Ethereum. It invites artists to imagine themselves as future media archaeologists, as recorders of our current information-based society, and as time-travelers highlighting the continued relevance of our long past. Will you dig for the digital, brush the dirt off the non-material, or excavate the internet?

In an era that threatens to be a digital dark age for future historians [1], blockchains may prove to be rare digital artefacts valuable enough to preserve into the future. There are already dozens of dead chains from abandoned cryptocurrencies [2], but with billions of dollars of value tied up in Bitcoin, Ethereum and other leading coins, the incentives to maintain their public ledgers are strong. Culture and knowledge have already been hidden in the blockchain – from images of Nelson Mandela to WikiLeaks cables [3] – but it is the blockchain as a record of our economic activity that concerns us here. This already has its history; on these public digital ledgers we can find everything from the ten thousand Bitcoins that were used to buy two pizzas [4] to the fifty million dollars of Ether that were stolen [5] in a hack on code running on the Ethereum blockchain. We just don’t have the best tools to visualise them yet.

We invite proposals for a new artistic online commission that takes the blockchain as the site of its manifestation. For example, artworks that are:

Whatever it is, it should work as a future media archeological artefact of blockchain finance and it has to be exhibitable online.

Hailed as both emancipatory opportunity for creative autonomy, and a driver of inequality and corporate opacity, the blockchain [10] is widely described as the Internet of Money. The blockchain is overtaking the WWW as the next big network technology for speculation and disruption. Investors recognise its potential in numerous ways: for high level authentication of identity [11] and matter [12]; for more efficient and secure financial transactions and distribution of digital assets; for communications so secure as to facilitate voting; and as a coordinating technology for the billions of devices connected to the Internet [13]

50 years ago this year, the world’s first ATM was designed, built and shipped from Dundee and installed in Enfield, less than 10 miles from Furtherfield. With this commission Furtherfield and NEoN recognise the role that the city of Dundee has played in the history of the development of smart technologies for financial transactions, through it being home to the R&D wing of The National Cash Register Corporation – NCR. [14]

NEoN Digital Arts Festival 2017 will expand on it being Scotland’s Year of History, Heritage and Archaeology, and seek to use its arts programme to unveil hidden histories through the practice of ‘media archaeology’. Media archaeologists uncover and reconsider the obsolete, persistent, and hidden material cultures of the technological age – from big data software algorithms to tiny silicon chips. With support from the National Lottery through Creative Scotland’s Open Project Fund, and Creative Europe Programme of the European Union, NEoN and Furtherfield invite artists to consider how the blockchain is the new ATM of the future.

The commission will be launched online and at NEoN Digital Arts Festival, and presented at the Digital Futures programme at V&A Museum and MoneyLab both in London in Spring 2018 as part of the European collaboration, State Machines which investigates the new relationships between states, citizens and the stateless made possible by emerging technologies.

Open Call announced 11th August

Deadline 4th September

6-9 September – follow up conversations where necessary (by email/phone)

13th September – decision made, artists informed and announced

19th September – public debate about cryptocurrencies in Dundee (organised by Scotcoin https://www.meetup.com/scotland-and-digital-currency/events/242087813/)

9th October – selected artist give progress report

9th November – Work installed for opening of NEoN Festival, Dundee. Artist presents work

Spring 2018 – Work re-presented with MoneyLab and V&A Digital Futures

(Note an additional £500 is available for accommodation and expenses for attendance at events in Dundee and London)

Submissions must include a proposal:

Documents should be submitted as PDFs or as links to a Google Doc, a GitHub Repo, or another easily read and easily accessed format.

If you have questions or enquiries about this commission please email alison.furtherfield[AT]Gmail.com

Notice of submissions via the Bitcoin blockchain should be sent via an OP_RETURN message starting with the word FField followed by a single space and the url of the proposal. E.g.:

FField https://docs.google.com/document/d/2oGsmli7Mlm-M_CZkL8WTKM3oUU3a

OP_RETURN messages can be created using the Crypto Grafitti service:

http://www.cryptograffiti.info/

Notice of submissions via Keybase messaging, or submissions of documents via KeybaseFS should be sent to:

(Note: Keybase does require registration but is free to join.)

Notice of submissions, or submissions of documents via email can be sent to ruth.catlow[AT]furtherfield.org

Please use the subject line “Furtherfield NEoN Proposal”.

Furtherfield

Through artworks, labs and debate around arts and technology, people from all walks of life explore today’s important questions. The urban green space of London’s Finsbury Park, where Furtherfield’s Gallery and Lab are located, is now a platform for fieldwork in human and machine imagination – addressing the value of public realm in our fast-changing, globally connected and uniquely superdiverse context. An international network of associates use artistic methods to interrogate emerging technologies to extend access and grasp their wider potential. In this way new cultural, social and economic value is developed in partnership with arts, research, business and public sectors.

NEoN

NEoN (North East of North) based in Dundee, Scotland aims to advance the understanding and accessibility of digital and technology driven art forms and to encourage high quality within the production of this medium. NEoN has organised 7 annual festivals to date including exhibitions, workshops, talks, conferences, live performances and public discussions. It is a platform to showcase national and international digital art forms. By bringing together emerging talent and well-established artists, NEoN aims to influence and reshape the genre. We are committed to helping our fabulous city of Dundee, well known for its digital culture and innovation, to become better connected through experiencing great art, networking and celebrating what our wee corner of Scotland has to offer in the field of digital arts.

State Machines: Art, Work and Identity in an Age of Planetary-Scale Computation

Focusing on how such technologies impact identity and citizenship, digital labour and finance, the project joins five experienced partners Aksioma (SI), Drugo More (HR), Furtherfield (UK),Institute of Network Cultures (NL) and NeMe (CY) together with a range of artists, curators, theorists and audiences. State Machines insists on the need for new forms of expression and new artistic practices to address the most urgent questions of our time, and seeks to educate and empower the digital subjects of today to become active, engaged, and effective digital citizens of tomorrow.

V&A Digital Futures: Digital Futures

V&A Digital Futures: Digital Futures is a monthly meetup and open platform for displaying and discussing of work by professionals working with art, technology, design, science and beyond. It is also a networking event, bringing together people from different backgrounds and disciplines with a view to generating future collaborations.

Creative Scotland

Creative Scotland is the public body that supports the arts, screen and creative industries across all parts of Scotland on behalf of everyone who lives, works or visits here. It enables people and organisations to work in and experience the arts, screen and creative industries in Scotland by helping others to develop great ideas and bring them to life. It distributes funding from the Scottish Government and The National Lottery.

This project has been funded with the support from the European Commission. This communication reflects the views only of the author, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein.

The Gathering Cloud makes slow reading. Let’s start with the title. It trips off the tongue, doesn’t it? Rolls around in the mind like a marble you’ve had since childhood. But there’s something unfamiliar about it, too. ‘The gathering cloud’ evokes a threat – the gathering crowd, perhaps; words haunted by expectation; a riot just about to begin. The gathering cloud sounds material and immaterial at the same time. It could signal rain, or warmth, or happiness for shepherds and fishermen, if only you knew how to read it. Could the ancients interpret celestial data? Can Google analysts do it now?

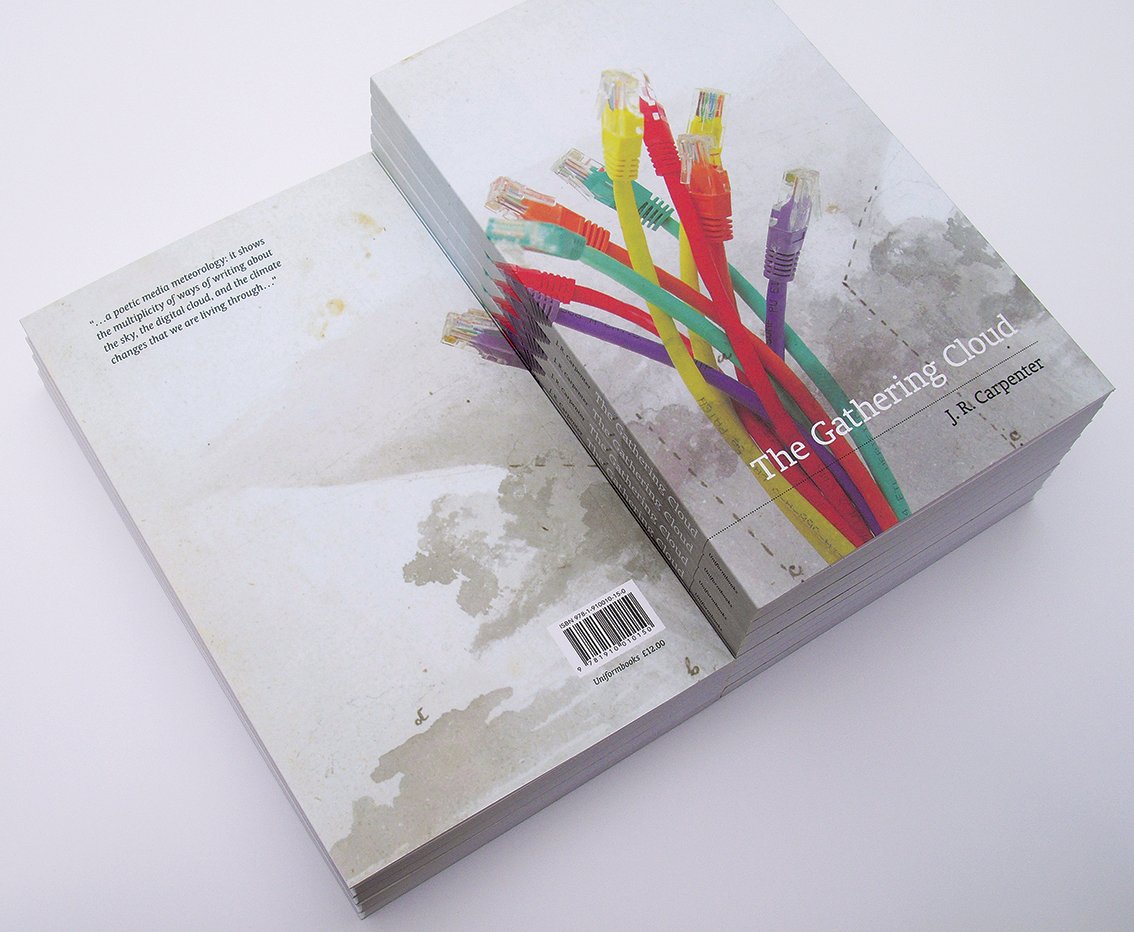

Every sentence in JR Carpenter’s literary artwork, The Gathering Cloud, is as resonant and expansive as its title. The work is so full of meaning, in fact, that it pushes beyond its own borders. Both a piece of digital literature commissioned by Neon Digital Arts Festival, and a book published by Uniform Press, The Gathering Cloud hovers, as an aesthetic experience, in between (it also exists as a printed A3 zine, distributed in more informal ways).

Its theme is climate change. Or, more precisely, the material effects of technologies euphemistically named ‘cloud computing’ on the health of the planet. Or the systems of knowledge that reveal and obscure our relationships to our world. Or the impossible responsibility of human actions that have a global impact. Or, in Carpenter’s characteristically succinct language in the afterword (‘Modifications on The Gathering Cloud’):

The Gathering Cloud aims to address the environmental impact of so-called ‘cloud’ computing and storage through the overtly oblique strategy of calling attention to the materiality of the clouds in the sky.

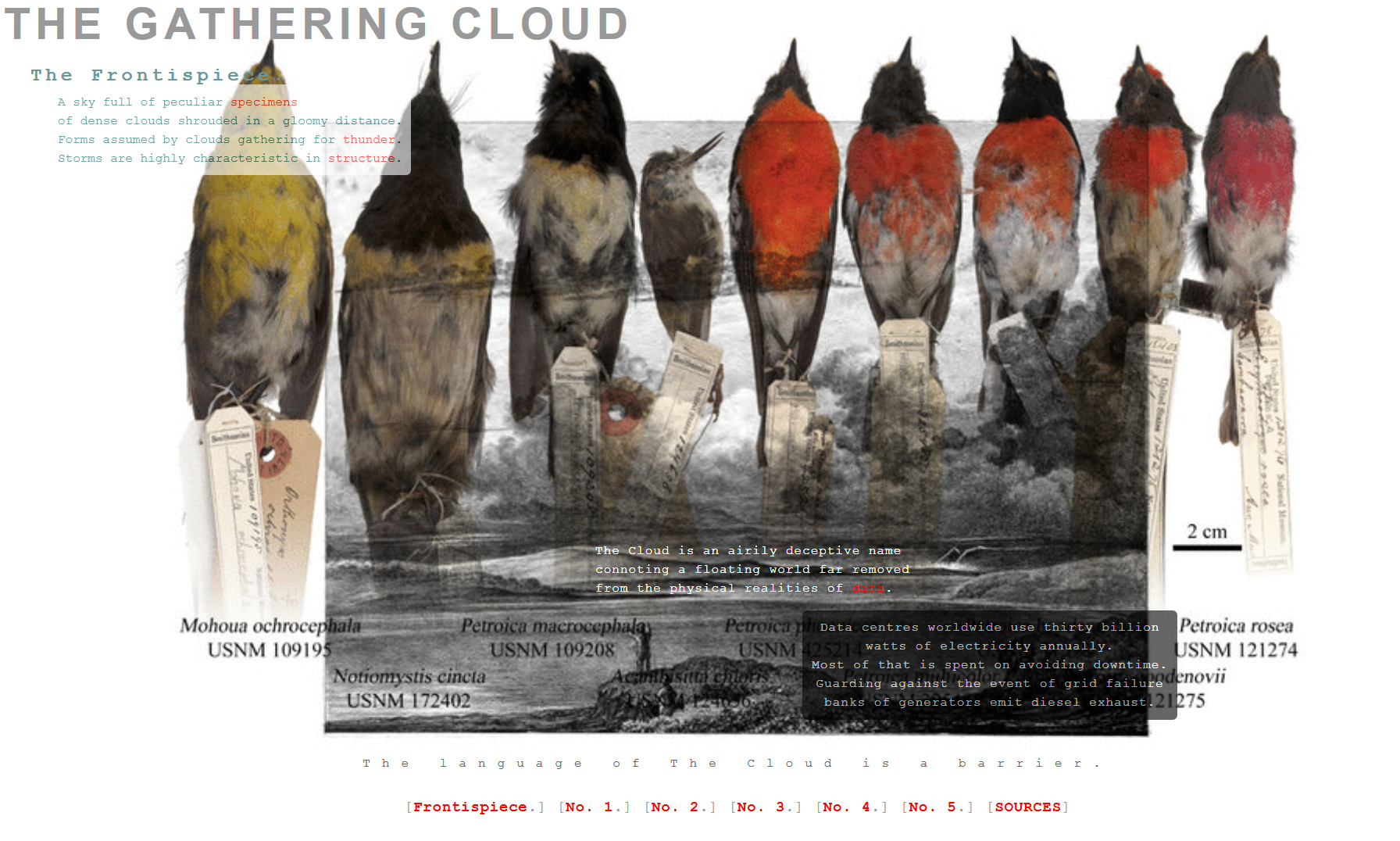

Online, The Gathering Cloud appears as a palimpsest of moving images, interacting as a series of animated gifs. To read this work is to move with it. Fragments of text respond to the hover of your mouse. Symbols march across the screen and align in multiple combinations. The experience, in other words, is just like using the internet. There is more here than you will ever be able to discover, and yet the format entices you to keep looking. The world of the browser is both (seemingly) infinite, and controlled by your gaze.

The first images you see are cloudscapes taken from Luke Howard’s Essay on the Modifications of Clouds (1803). Howard was the first person to devise a popular and scientific naming system for the clouds in the sky. His process was based on natural history classifications, Latin naming principles and the fact that clouds are subject to endless change. His project was such a success that we still use his cloud nomenclature today. But, as Carpenter points out, ‘The language of The Cloud is a barrier.’ Here, she is talking of the language of cloud computing, and how its association with the mutable territory of the sky fails to communicate its dirty, real-world effects. But the language of the clouds is also, always, a reference to Howard’s system and its structuring aim: a grand attempt to explain the (previously) unexplainable, to box in the search for knowledge, to capture what is not still there.

The illustrations that accompanied Howard’s published text were minutely detailed etchings based on his own watercolours. In the book, Carpenter describes the journey of the images as technological as well as scientific artefacts, ‘Translated into cross hatching,’ she writes,

Howard’s studies

lost subtlety, but gained fixity, moving

them toward the diagrammatic scientific.

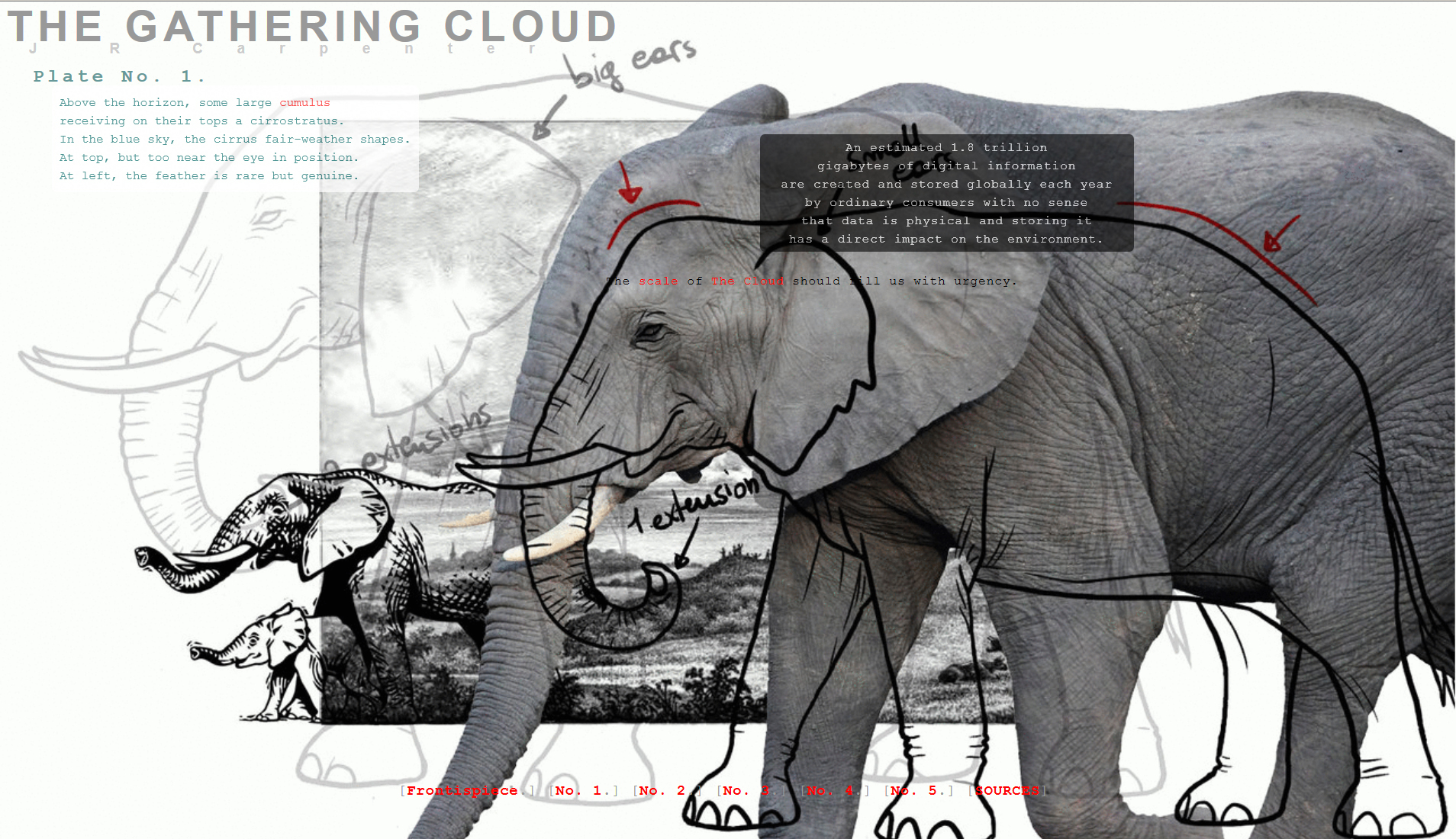

Carpenter uses these pictures, then, to draw attention to how we understand the world as well as what we (try to) understand. Onscreen, she overlays them with photographs and illustrations of animals – elephants, birds, beetles – which echo metaphors evoked in fragments of her poetic text (‘A cloud the weight of one hundred elephants’, for example, ‘How many more birds/ have been captured and tagged and stored in The Cloud?’). Like the etchings, these animal images bear the time-stamp of specific systems of thought. Some are scientific and precise, for example, and belong, stylistically, to a process of classification: illustration as pedagogic tool.

In a final conceptual twist, each of these interwoven, visual elements has been ‘materially appropriated’ (Carpenter writes), ‘from publicly accessible cloud storage services.’ These, then, are pictures of weather clouds, and of the ways we think about weather clouds, and of the technological border patrols that control the ways we think. These are images preserved in the hardware of server farms, which means they are also images of the billow of fossil fuels, the gasp of countless lives and minerals, ground into the earth over geological time, as unimaginable in scale as the size of the data stores themselves, or the climate change precipitated by the energy they need.

Tech giants Apple, Amazon and Microsoft

power their twenty-first century clouds with

dirty nineteenth-century coal energy.

And here is the context for Carpenter’s words: lines of hendecasyllabic (eleven-syllable) verse arising inside, on top of or behind the images, borrowing and interpreting found texts from Howard’s nomenclature and contemporary media studies. All of this, finally, is the context for you: the reader/user, dragging your finger across your mouse pad as you enact the dynamic complexity The Gathering Cloud represents:

To miniscule cumulus water droplets

air is an upwelling thermal below them

is as dense as honey is to a pebble

five thousandths of a millimetre across.

As a work of digital literature, then The Gathering Cloud is an extraordinary marriage of concept and content. By which I mean literally extra-ordinary: representing and exceeding the ordinary functions of its source images and texts. While the work is hosted online, however, its rhizomatic affect has less to do with technology than with attention. In an interview in 2010 Carpenter said, ‘I imagine my target audience being people sitting at desks pretending to do other things. Like work, for example. Or writing. Because they are already pretending, their minds are wide open. [1]’ The Gathering Cloud is a lucid dream space for people not entirely in charge of their dreams.

*

The most obvious difference between the printed and online versions of The Gathering Cloud is that the book feels primarily textual. Featuring an extended prologue, the book showcases Carpenter’s writing on spacious pages, interspersed with occasional black and white ‘plates’ taken from the digital piece. Simply framed in this way, the power and precision of her words come to the fore. The hendecasyllable format produces a bare, pared down kind of language that sounds natural and restrained, like a conversation with someone who has much more to say. Describing the ancient Roman philosopher Lucretius’ theory of clouds, for example, Carpenter writes:

Nothing can be created out of nothing.

The whole earth exhales a vaporous steam.

Meaning hangs like a lifetime between these lines. The gap between ‘nothing’ and the exhalations of the earth is as big and as small as a breath being held.

Like the skeleton of a bird’s wing, each line in Carpenter’s perfectly crafted, fragile text takes the body of the work in a new direction. And yet, the most thrilling element of the book is not textual, but visual.

In print, some of the words appear greyed out. Twenty-first century readers recognise this allusion, immediately, as a hyperlink; but of course, there is nothing to click on a printed page. A book is an emblem of past decisions in a way that online experiences pretend not to be. These un-links, then, are uncanny. They promise potential, in the same moment as they fatally disappoint. They wave to the future but they are, literally, pulped emulsions of the past. They call to a space beyond the page, ripe with forbidden fruit, humming with endless desire: more knowledge, more dreaming, more distraction.

An estimated 1.8 trillion

gigabytes of digital information

are created and stored globally each year

by ordinary consumers with no sense

that data is physical and storing it

has a direct impact on the environment.

These un-links represent everything you want and everything you can’t have. They are the spaces for you to dream in and the alarm that stops you dreaming. They are the endless potential of the internet, and the finite resource that will shut it down. In other words, just as the online version of The Gathering Cloud performs the limits and aspirations of older systems of thought – the acid hatch of etchings, the earnest naivety of visual or linguistic classification – so the printed work performs the futile urgency of lives lived online. In each case, the performer on centre stage is the reader/viewer, forced to confront her own ambitions and her impotence as she navigates through mutable worlds.

This, in a nutshell, is our relationship with climate change: it is about us, but bigger than we can comprehend; we are compelled to act, but crave direction; we want to dream, but we are afraid to lose. Crucially, Carpenter asks us to inhabit this relationship, not the climate itself: her work is emotional, not didactic. Instead of explaining climate change, Carpenter explores the extent to which it can possibly be imagined. Then, gently but firmly, she pushes the borders of our thoughts, and gets us to imagine some more.

‘Like a muzzled creature’, Carpenter writes, ‘the cloud strains to be/more than it is.’ The same could be said for her work, of course, and for the people who move through it. In a perfect echo of the systems of weather and data that are its subject, different iterations of the The Gathering Cloud (whether real or imagined) are held, within the reader, as memory, as action, and as technology of thought. The Gathering Cloud could signal rain, or warmth, or happiness for idle browsers,if only you could trace your finger along each acid scratched line. Could the ancients sculpt the hubris of the searching gaze? Can the Google server farms do it now?

By Mary Paterson

Review of The Gathering Cloud, JR Carpenter

http://luckysoap.com/thegatheringcloud/

Uniform Books, 2017