This is a long read by one of the inhabitants of the Zad, about the the fortnight rollercoaster of rural riots that has just taken place to evict the liberated territory of the Zad. It’s been incredibly intense and hard to find a moment to write, but we did our best. This is simply one viewpoint, there are over 1000 people on the zone at the moment and every one of them could tell a different story. Thank you for all the friends and comrades who helped by sharing their stories, rebel spirits and lemon juice against the tear gas.

“We must bring into being the world we want to defend. These cracks where people find each other to build a beautiful future are important. This is how the zad is a model.” Naomi Klein

“What is happening at Notre-Dame-des-Landes illustrates a conflict that concerns the whole world” Raoul Vaneigem

The police helicopter hovers above, its bone rattling clattering never seems to stop. At night its long godlike finger of light penetrates our cabins and farm houses. It has been so hard to sleep this last week. Even dreaming, it seems, is a crime on the Zad. And that’s the point: these 4000 acres of autonomous territory, this zone to defend (Zad), has existed despite the state and capitalism for nearly a decade and no government can allow such a place to flourish. All territories that are inhabited by people who bridge the gap between dream and action have to be crushed before their hope begins to spread. This is why France’s biggest police operation since May 1968, at a cost of 400,000 euros a day, has been trying to evict us with its 2500 gendarmes, armoured vehicles (APCs), bulldozers, rubber bullets, drones, 200 cameras and 11,000 tear gas and stun grenades fired since the operation began at 3.20am on the morning of the 9th of April.

The state said that these would be “targeted evictions”, claiming that there were up to 80 ‘radical’ Zadists that would be hunted down, and that the rest, the ‘good’ Zadists, would have to legalise or face the same fate. The good zadist was a caricature of the gentle ‘neo rural farmer’ returning to the land, the bad, an ultra violent revolutionary, just there to make trouble. Of course this was a fantasy vision to feed the state’s primary strategy, to divide this diverse popular movement that has managed to defeat 3 different French governments and win France’s biggest political victory of a generation.

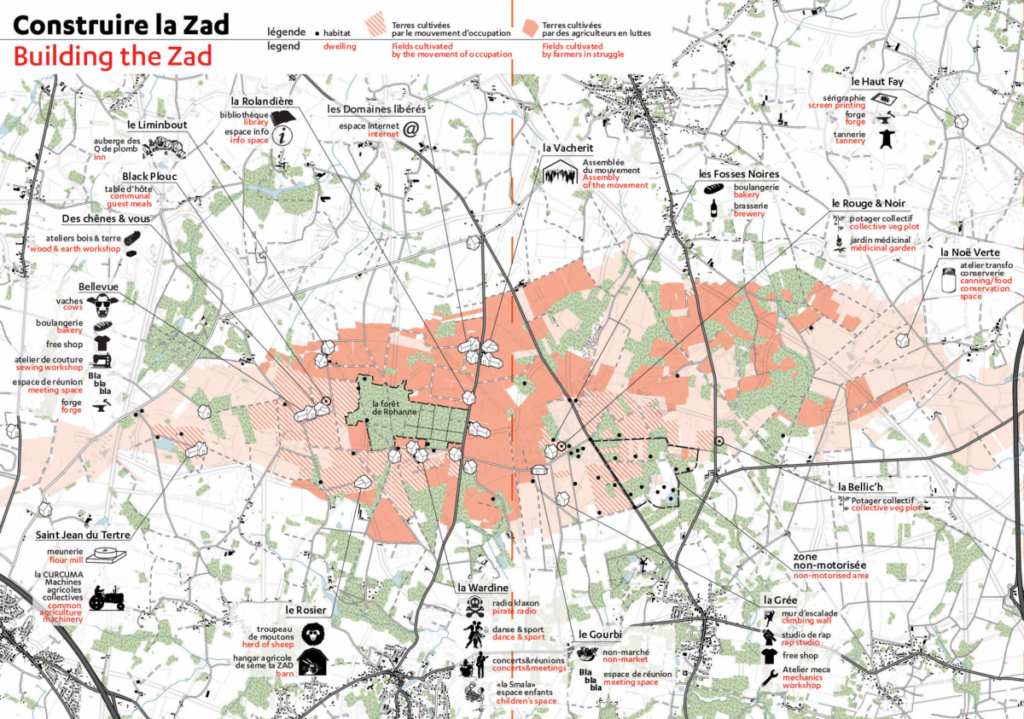

The zad was initially set up as a protest against the building of a new airport for the city of Nantes, following a letter by residents distributed during a climate camp in 2009, which invited people to squat the land and buildings: ‘because’ as they wrote ‘only an inhabited territory can be defended’. Over the years this territory earmarked for a mega infrastructure project, evolved into Europe’s largest laboratory of commoning. Before the French state started to bulldoze our homes, there were 70 different living spaces and 300 inhabitants nestled into this checkerboard landscape of forest, fields and wetlands. Alternative ways of living with each other, fellow species and the world are experimented with 24/7. From making our own bread to running a pirate radio station, planting herbal medicine gardens to making rebel camembert, a rap recording studio to a pasta production workshop, an artisanal brewery to two blacksmiths forges, a communal justice system to a library and even a full scale working lighthouse – the zad has become a new commune for the 21st century. Messy and bemusing, this beautifully imperfect utopia in resistance against an airport and its world has been supported by a radically diverse popular movement, bringing together tens of thousands of anarchists and farmers, unionists and naturalists, environmentalists and students, locals and revolutionaries of every flavour. But everything changed on the 17th of January 2018, when the French prime minister appeared on TV to cancel the airport project and in the same breath say that the zad, the ‘outlaw zone’ would be evicted and law and order returned.

I am starting to write 8 days into the attack, it’s Tuesday the 17th of April my diary tells me, but days, dates even hours of the day seem to merge into a muddled bath of adrenaline socked intensity, so hard to capture with words. We are so tired, bruised and many badly injured. Medics have counted 270 injuries so far. Lots due to the impact of rubber bullets, but most from the sharp metal and plastic shrapnel shot from the stun and concussion grenades whose explosions punctuate the spring symphony of birdsong. Similar grenades killed 21 year old ecological activist Remi Fraise during protests against an agro industrial damn in 2014.

The zad’s welcome and information centre, still dominated by a huge hand painted map of the zone, has been transformed into a field hospital. Local doctors have come in solidarity working with action medic crews, volunteer acupuncturists and healers of all sorts and the comrades ambulance is parked outside. The police have even delayed ambulances leaving the zone with injured people in them, and when its the gendarmerie that evacuates seriously injured protesters from the area sometimes they have been abandoning them in the street far from the hospital or in one case in front of a psychiatric clinic.

The thousands of acts of solidarity have been a life line for us, including sabotaged French consulate parkings in Munich to local pensioners bringing chocolate bars, musicians sending in songs they composed to demonstrations by Zapatistas in Chiapas, banners in front of French embassies everywhere – from Dehli to New York, a giant message carved in the sand of a New Zealand beach and even scuba divers with an underwater banner. Here on the zone three activist field kitchens have come to feed us, architects have written a column deploring the destruction of unique forms of habitat signed by 50,000 people and locals have been offering storage for the safe keeping of our belongings. A true culture of resistance has evolved in parallel with the zad over the years. Not many people are psychologically or physically prepared to fight on the barricades, but thousands are ready to give material support in all its forms and this is the foundation of any struggle that wants to win. It means opening up to those who might be different, those that might not have the same revolutionary analysis as us, those who some put in their box named ‘reformist’, but this is what building a composition is all about, it is how we weave a true ecology of resistance. As a banner reads on one of the squatted farmhouses here, Pas de barricadieres sans cuisiniers “There are no (female) barricaders without (male) cooks.”

Today has been one of the calmest since the start of the operation, and it felt like the springtime was really flowering, so we opened all the doors and windows of house letting the spring air push away the toxic fumes of tear gas that still linger on our clothes. It feels like there is a momentary lull. For the first time since the evictions, our collective all ate together, sitting in the sun at a long table surrounded by two dozen friends from across the world come to support us. I hear the buzzing of a bee trying to find nectar and look up into the sky, its not a bee at all, but the police drone, come to film us sharing food, it hovers for hours. In the end this is the greatest crime we have committed on the zad, that of building the commons, sharing worlds together and deserting the pathology of individualism.

Two years before the abandonment of the airport project the movement declared in a text entitled The Six Points for the Zad: Because there will be no Airport, that we would, via an entity that emerged from the movement , collectively look after these lands that we were saving from certain death by concrete. A few months before the abandonment the form that this entity took was the Assembly of Usages. Soon after thethe airport was cancelled, we entered into negotiations with the state (via the prefet. Nicole Klein, who represents the state in the department) following a complicated week of pre-negotiations, where we were forced to open up one of the roads which had had cabins built on it since the attempted evictions of 2012. It seemed that the flow of traffic through the zone was the state’s way of telling the public that law and order had returned on the zone. (see the text Zad Will Survive for a view of this complicated period).

A united delegation of 11 people made up from the NGOs, farmers, naturalists and occupiers of the zone attended the negotiations and did not flinch from the demand to set up a collective legal land structure, rather than return these lands to private property and agro-business as usual. In the 1980s a similar legal structure was put in place following the victory of a mass movement against the expansion of a military base on the plateau of the Larzac in Southern France. With this precedent in mind we provided a legally solid document for a global land contract, but it was ignored, no legal grounds were given, the refusal was entirely political. Three days later the evictions began.

The battle lines were made clear, it was not about bringing ‘law and order’ back to the zone, but a battle between private property, and those who share worlds of capitalism against the commons. The battle of the Zad is a battle for the future, one that we cannot loose.

The telephone rings, it’s 3.20am, it’s still dark outside, a breathless voice says two simple words, “It’s begun !” and hangs up. Everyone knows what to do, some run to offices filled with computers, others to the barricades, some to the pirate radio (Radio Klaxon, which happens to squat the airwaves of Vinci motorway radio, 107,7, the construction company that was going to build and run the airport) others start their medics shift. Hundreds of police vans are taking over the two main roads that pass through the zone.

Fighting on one of the lanes manages to stop the cops moving further west. But elsewhere the bulldozers smash their way through some of the most beautiful cabins made of adobe and the wastes of the world that rose out of the the mud in the east of the zone, they destroy the Lama Sacrée with its stunning wooden watch tower, permaculture gardens and green houses are flattened and they rip gashes in the forest. A large mobile anti riot wall is erected by the police in the lane that stretches east to west, a technique that works in cities but in rural riots it’s useless and people spend all morning hassling them from every angle. Despite gas and stun grenades we hold our ground. Journalists are blocked for a while from entering, the police stating that they will provide their own footage (free of copyrights!). The “press group” gives them directions so that they manage to cross the fields and the pictures dominate the morning news.

There are over a dozen of us are facing a line of hundreds of robocops at the other end of the field. One of us, masked up and dressed in regulation black kway is holding a golf club. He kneels down and places a golf T in the wet grass. He pulls a golf ball out of a big supermarket bag and serenely places it in the T. He takes a swipe, the ball bounces off the riot shields. He takes out another ball and another and another.

In the afternoon the cops and bailiffs arrive at the 100 noms, an off grid small holding with sheep, chickens, veg plots, and beautiful housing including a cabin built by a young deserting architect which resembles a giant knights helmet made with geodesic plates of steel. The occupiers, who have built this place up from nothing over 5 years are given 10 minutes to leave by the bailiff. Several hundred people turn up to resist, many from ‘the camp of the white haired ones’ which hasbrought together the pensioners and elders, who have called it a camp for “the youth of all ages” and have been one of the backbonesof this long struggle. There must be nearly 200 of us, at the 100 noms, this time no one is masked up. A massive block of robocops is coming up the path, some of us climb on the roof of the newly built sheep barn, others form a line of bodies pressed hard against the riot shields, we are peasants and activists, occupiers and visitors, young and old and they beat us, burn our skin with their pepper spray and push us out of the fields.

We reply with a joyful hail of mud that covers their visors and shields. The people on the roof are brought down by the specialists climbers and the bulldozer does its job. A few minutes later a one of their huge demolition machines gets stuck in the mud, a friend shouts ironically to the crowd: “come on let’s go and give it hand and push it out!”, Hundreds approach, trails of gas take over the blue sky, dozens of canisters rain down on the wetlands, many falling into the ponds which begin to bubble with their toxic heat. I try to console Manu whose home, a tall skinny wooden cabin with a climbing wall on its side, has just been flattened, my hugs cannot stop his sobs. Our eyes are red with tears of grief and gas.

In the logic of the state, the 100 Noms ticked many of their fantasy boxes of those want to be legalised, ‘the good Zadists’. It was a well functioning small holding, producing meat and vegetables and where the sheep were more legal than its inhabitants. It was a project that had the support of many of the locals. Its destruction lit a spark that brought many of those in the movement who had felt a bit more distant from the zad recently back into the fold of the resistance. Of course its no less disgusting than the flattening of all the other homes and cabins, but the battle here is as much on the symbolic terrain as in the bocage and it is seems to be a strategic blunder to destroy the 100 Noms.

The live twitter videos from the attack are watched by tens of thousands, news of the evictions spreads and a shock wave ripples through France. Actions begin to erupt in over 100 places, some town halls are occupied, the huge Millau bridge over 1000 km away is blockaded as is the weapon factory that makes the grenades in Western Brittanny.

The demolition continues till late, but the barricades grow faster at night, and we count the wounded.

It all begins again before sun rise, the communication system on the zone with its hundreds of walkie talkies, old style truck drivers cb’s and pirate radio station calls us to go and defend the Vraie Rouge collective, which is next to the the zad’s largest vegetable garden and medicinal herb project. We arrive through the fields to find one of the armoured cars pushed up against the barricade, we stand firm the barricade between us and the APC. We prepare paint bombs to try and cover the APC’s windows with. Then the tear gas begins to rain amongst the salad and spinach plants. A friend finds a terrified journalist cowering in one of the cabins, she writes for the right wing Figaro newspaper and is a bit out of place with her red handbag. “What’s that noise??” she asks, trembling, “the stun grenades” he replies. “But why aren’t you counter attacking?” she says, “where are your pétanque balls covered in razor blades?” Our friend laughs despite the gas poisoning his lungs, “we never had such things, it was a right wing media invention, and it’s impossible anyway, no one can weld razor blades onto a pétanque ball! ”

There is so much gas, we can no longer see beyond our stinging running noses. The police are being pressurised simultaneously from the other side of the road by a large militant crowd with gas masks, make shift shields, stones, slingshots and tennis rackets to return the grenades. They are playing hide and seek from behind the trees. The armoured car begins to push the barricade, some of us climb onto the roof of the two story wooden cabin, others try to retreat without crushing the beautiful vegetable plot. Its over, the end of another collective living space on the zone. Then we hear a roar from the other side of the barricade. Dozens of figures emerge from the forest, molotov cocktails fly, one hits the APC, flames rise from the amour and the wild roar transforms itself into a cry of pure joy. The APC begins to back off as do the police. The Vraie Rouge will live one more day it seems, thanks to diversity of tactics.

In 2012 when we managed to stop the first eviction attempts of the zone, this was what gave us an advantage. Over the 50 years that the movement against the airport lasted, it used everything from petitions to hunger strikes, legal challenges to sabotage, riots to citizens ecological inventories of the zone, defensive tree houses to flying rocks, tractor blockades to clown armies. Its secret weapon was the respect we had for each others’ tactics and an incredible ability to try and not condemn each other. Pacifist Pensioners and black bloc worked together in a way that I had never seen before, which made criminalising the movement much more complicated for the government. Movements win when they have the richest most colourful palette of tactics at their disposition and they are ready to use everyone of them at the right time and place.

In a woodland dip to the east of the zone, the Cheverie, is still resisting. A huge high cabin made from different types of swirling coloured clay – brown, grey, ochre and white – punctuated by mosaics and carved spiders, constructed by hundreds of hands, is about to be crushed. Hundreds of gendarmes surround it, one of them seems to have a machine gun strapped to his back. From the roof someone uses a traffic cone as a megaphone: “we are defending life and the living.” When the cabin is finally brought down a minor miracle occurs, none of the dozens of windows is broken, which will make it much easier to rebuild.

At the Fosses Noires, the brewery has been turned into a canteen, but the tear gas is falling on the pots, pans and piles of donated of vegetables. After lunch, a second press conference takes place, yesterday the first one had brought dozens of TV cameras and microphones from radios across the country, 8 people from all the composition of the movement faced the cameras, their dignified anger was so powerful, so palpable, many of us shed tears listening.

Today there are 30 inhabitants are in front of the cameras, it is those that have an agricultural and craft projects running on the zone, the tanner is there as is the cheese maker, the potter and market gardeners, cow herders and leather workers. They explain how over the last weeks of negotiations with the state, they handed over documents to develop a collective project within a legal non profit association that had been set up. They show that on this bocage to think ecologically is to realise that all the projects are interdependent, rotating the fields between folk, sharing tools and and everyone helping out on each others projects when needed. To divide the zad into individual separate units makes no sense.

But the words are not as strong as the striking image of Sarah, our young shepherdess who like a modern day madonna holds a dead black lamb on here lap. She explains how her flock was legalised already and that this one died from stress when it was moved from the 100 Noms farm to avoid the evictions. Her grey eyes pierce the camera lenses, “they chose violence, they chose to destroy what we build, they chose to break off the dialogue with us.” Whilem a young farmer, whose milk herd squats fields to the west, raises his trembling voice, “ If there is no collective agriculture then you get what’s already happening in the countryside – individualism: eat up your neighbours farm land, be more and more alone with a bigger and bigger farm,” he takes a deep breath, “the isolation is pushing farmers to commit suicide, we are more and more alone on our farms faced with increasing difficulties. On the zad we hold a vision of farming for all, not just for us.”

The zad makes a call for a mass picnic the following day. Vincent one of the supporting farmers from the region, a member of COPAIN 44, a network of rebel farmers whose tractors have become one of our most iconic and useful tools of resistance, sighs, “the government has broken any possibility of dialogue now, they have forced us to respond with a struggle for power.”

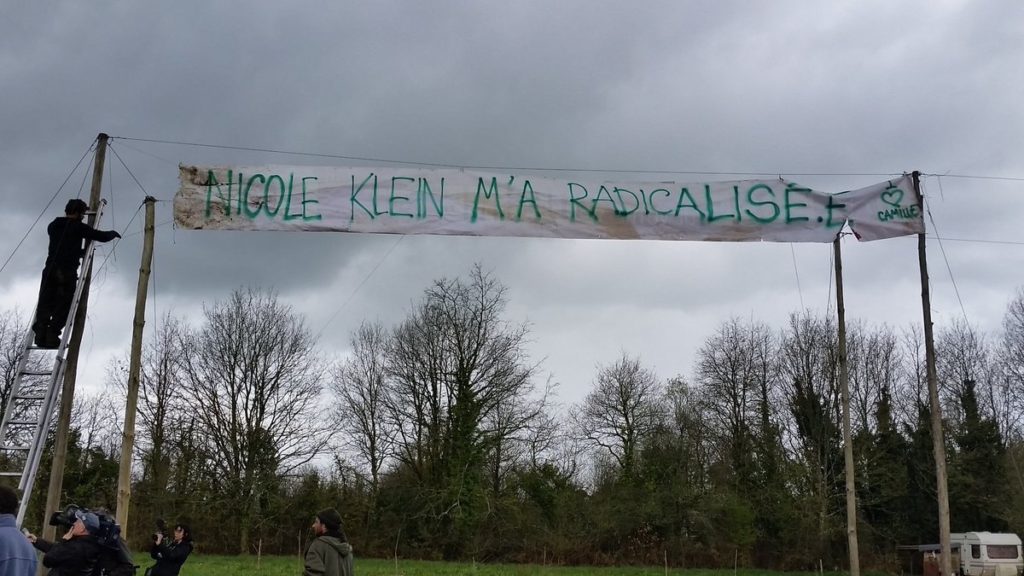

Between the tall poles that hold the breweries’ hop plants a long banner is raised, “Nicole Klein radicalised me.”

We are woken as normal by the explosions of gendarmes grenades, fighting continues near the D281 road. A small group is trying to stop the police lining up in a field, there aren’t many of us, it feels hopeless, then out of the morning mist comes a tractor, its driver wears a balaclava, in the front bucket – a tonne of stones. He drops them in a pile just where we are standing, puts the tractor in reverse and disappears back into the mist.

In the next door field a towering guy wearing a balaclava and dressed in a full monks habit throws a bucket of water over a handful of robocops – “I baptise you in the name of the zad”, he bellows. A cloud of pepper spray engulfs him, but one the gendarmes slips in the mud and drop his truncheon, at the speed of light the monk grabs it and runs off, wielding his rebel relic in the air. The police megaphone calls out “You must return the state’s property. Return it now!”

The picnic before it was gassed.

At lunch time, over a thousand people turn up to share a picnic in the fields. Over thirty tractors have come, some from far, despite the fact that its one of the busiest seasons for the farmers, they encircle the large Rouge et Noir collective vegetable garden, now littered with hundreds of toxic plastic tear gas canisters. “The state crossed the red line when they destroyed the 100 Noms” one of them says.

The crowd of all ages walk through the barricades and debris of yesterday’s battle that litter the country lanes. The atmosphere is festive, a samba band with pink masks leads us into the field beside the Lama Sacrée. A long line of black clad police stretches across the spring green pasture. The samba band approach, then all hell lets loose: gas canisters shower down, dozens of stun grenades are thrown into the peaceful crowd, panic ensues, people retreat across the hedgerows.

The houses of la Boite Noire, Dalle à Caca, Jesse James and la Gaité fall in the east. Simultaneously they attack la Grée, the large rambling grafitti covered farm at the centre of the zone that has an unconditional welcome policy. There is a car repair workshop, climbing wall and the rap studio and many folk escaping the misery of street life and addictions end up living there together. Farmers’ tractors are surrounding the building, a barricade made from the carcasses of cars, is set alight. But the tear gas is too strong and the tractors are forced to back off.

Out of the mist of gas come black lumbering troops, they charge across the fields. The whole zone is split in two by a seemingly endless lines of robocops stretching east to west. The crowd is dispersed, people are coughing up their lungs, they are furious. It began as a picnic, now it’s a war zone again. The gas clouds cling to the pasture, frightened cows huddle together in a corner of a tiny field. The medic post at the Fosses Noires has to move away to the Gourbi, but then the gas catches up with it there too and it moves to La Rolandière just in time before the police arrive to smash one of the zone’s most symbolic sites, the Gourbi.

In the very centre of the zad the Gourbi is where the weekly assembly of occupiers is held and Friday’s No-market, a place where excess produce is distributed with no fixed price but by donation only. Initially there was a stone farm house there, inhabited by an old couple who were evicted in 2012 and their home destroyed for the airport project. Then a wooden hut was built in its place, but its ramshackle pallet sides soon needed restoring and so a brand new state of the art cabin like meeting house was built over 2015. But one night someone sneaked into this beautiful meeting house and set it alight.

But Gourbi was to rise from the ashes, and as an ironic response to the governments 2016 local consultation about the airport project, we held an all night building party whilst the results came through (55% for building the new airport). To the sound of a wild one man accordion band doing kitsch covers of Queen and other trashy pop songs, hundreds of people stuffed the clay of the wetlands into a huge geodesic metal dome structure to build our new round meeting house. It was made of steel and mud to resist arson, but today the bulldozer crushed it with a single swipe of its blade. Worlds away in the metropolis, the Minister of Interior, Gérard Collomb, tells parliament “We want to avoid all violence in this country, this is what we are doing at Notre-Dame-des-Landes.”

By sunset the government claims to have evicted 13 more living spaces, bringing the total to 29 since Monday. The prime minister refuses to pause the operations, and the medic team share horrific photos of some of the 60 injuries since Monday, including 3 journalists. Meanwhile the cops release their figures: 32 injuries, but it turns out most are from the mis use of their own weapons. Solidarity actions pour in from thousands, including squatters in Iceland, farmers in Lebanon and eco builders in Columbia. In Paris, sex workers send in kinky zad themed S and M photos and students occupy the EHSS elite social science school in solidarity. That afternoon electricity is cut across a large part of the zone and many of our neighbors homes outside of the zad. It is a tactic reminiscent of collective punishment used during military occupations , At night the gentle lulling croak of mating frogs in the marches mixes with the hum of back up electric generators. Four hundred of us meet at the Wardine, in the old concrete cow shed covered in bright murals, we share stories, dogs bark, tempers fray.

The day begins with some good news on radio klaxon. An affinity group action just shut down the motorway that passes near the zad. Emerging from the bushes they flowed down onto the tarmac armed with tyres, fluorescent jackets and lighters. Within seconds a burning wall blocked the flow of commuters to Nantes. The group disappeared just as quickly as they materialised, melting back into the hedgerows. The more we fight for this land, the more we become the bocage and the harder it is to find us. Every day more and more people converge here, many for the first time in their lives.The art of the barricade continues across the zone, including one topped with an old red boat. Some of our most useful barricades are mobile, in the form of tractors, dozens of COPAIN 44’s machines take over the main cross roads of the zone.

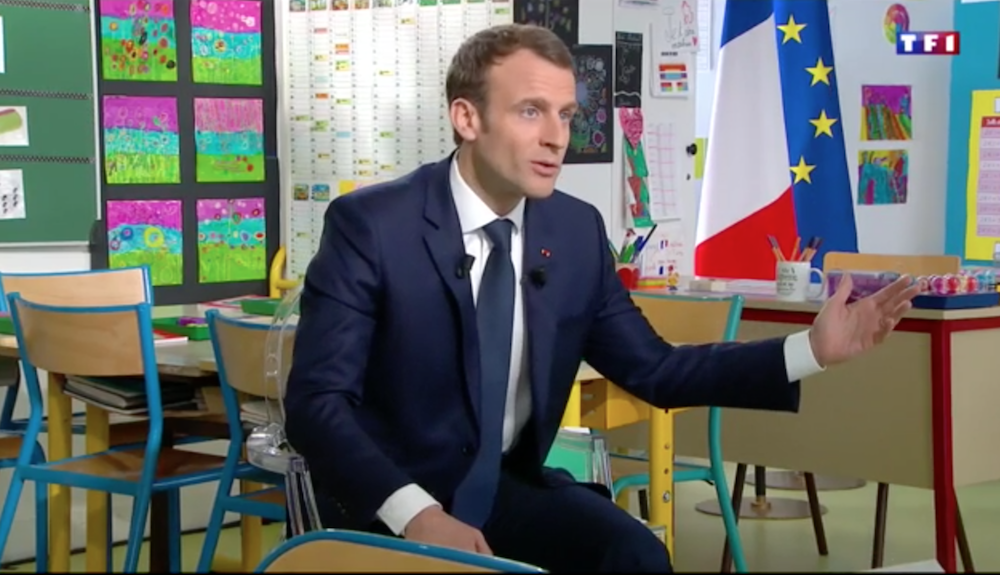

Following an attempt by friendly lawyers to prove that the eviction of the 100 noms was illegal, the prefect is forced to appear in court in Nantes, but the case is adjourned. The indefatigable zad press group sends out a new communique entitled, After 3 days of evictions are they ready to kill because they don’t want a collective ? Clashes continues across the bocage as Macron take to the TV screens for a national statement about his policies. A social movement is rising against him, with university occupations, supermarket, rail workers and Air France on strike – he has to respond. The mise-en-scène is bizarre, he sits in a primary school class room. He speaks about the zad for a little over a minute, “republican order must be returned” he says, and “everything that was to be evacuated has already been evacuated”.

As he speaks a hundred and fifty concussion grenades are launched in less than half an hour in the Lama Sacrée field, the explosions echo across the bocage, bursting the ear drums of those nearby and raising the anxiety levels of those within hearing distance, which on this flat landscape of the zad, is all of us. The league of Human Rights demands that all parties come back to the table. A call is sent for people to converge on the Zone on Sunday: “ The time has come to find ourselves together, to say that the zad must live, to dress our wounds and re build ourselves..” …

We walk home to la Rolandière, with its ship shaped library attached to the lighthouse, built where they wanted to build the airport control tower. The sun is setting, 20m high up on the lighthouse’s balcony a lone figure is playing a trumpet, fluid sumptous jazz floats across the forest. It is one of those moments when you remember why you live here.

That night under a clear constellation filled sky, the Assembly of Usages meets. We sit on wooden hand made bleechers under Le hangar de l’avenir (The Barn of the future). This cathedral like barn was built by over 80 traditional carpenters in 2016 using mostly hand tools, it is ornamented with snakes and salamanders carved into the oak beams. There are several hundred of us at the assembly, one of the peasants whose tractor is blocking the crossroads reads out a series of texts messages he has received from the préfete who is trying to negotiate with COPAIN 44. “Yesterday the Prime minister said it was war, today the president says its peace, therefore it’s all over.” It’s clear that she’s feeling that the situation has become much more complicated than predicted. A deal is made, move your tractors she writes, and I promise that by 10pm I will announce to Ouest France, the regional news paper, that it is the end of operations by the Gendarmes.

The meeting continues, we wait for the article to appear on the newspaper’s web site. I reload my phone endlessly waiting for the site to update. Suddenly it does, but it’s just a story about rock legend Johnny Hallyday, was it all a bluff ? Then it arrives, half an hour late. A cheer rises from the tired voices. At home we try to party a little, at least we might get a lie in tomorrow morning, it seems that it’s over for the time being?

I’m half awake, there is a rumble of vehicles on the road… At first I think it’s tractors, then I see the lights, blue and flashing, van after van of cops passing. We leap out of bed and run to the top of the lighthouse, the entire road is filled with vans as far as the eye can see. The huge barricade at the crossroads, which the tractors left last night following the préfete’s announcement, is on fire, a plume of black smoke frames the the orange dawn. The familiar pop of tear gas canisters being fired is accompanied by the crunching sounds of barricades being pushed by the APC. Radio Klaxon says they have kettled la Grée and are searching it, the Wardine camping is also encircled and a hundred and fifty cops are heading towards the Rosier. The Lascar barricade, made of several burnt cars, with a huge metal doorway and a trench that is several meters wide, is being defended by a nearly 100 of us. The forest is wrapped in toxic mist, ghostly rebel silhouette run from tree to tree, stones are aimed at the robocops with catapults that were made by Andre, an 83 year old who set up a production line for us during the eviction threats of 2016, his team churned out 1000. The cops throw stun grenades blindly from the fields into the forest, one explodes just above my head, caught in the tree it rips the bark into smithereens. Is this what they call the end of operations ?

A communiqué from the gendarmerie explains that they are clearing the roads and are not doing any expulsions or knocking down any squats, but that they are looking to arrest people who fired a distress rocket at their helicopter. At la Grée they take away two people but not for that charge. The gas pushes everyone back from the Lascar’s barricade and the grinders come out to cut the metal gateway into pieces. Despite the rising clouds of tear gas, people on the roof of the brand new Ambazada, a building that will host folk from intergalactic struggles, manage to sing some of our re purposed folk songs, recount the history of the struggle of the zad.

Then a moment of joy, one of the armoured cars attacking the Lascar tips into a ditch and has to be pulled out by the other one. The mud of this wetlands has always been our ally, its wetness our friend. When they retreat a banner is put up, “Cheap APC driving license available here.” Our other accomplice is humour of course, even in what feels like a war zone, with tarmac scorched, broken glass and rubble everywhere, being able to laugh feeds our rage. The police retreat again and the barricade grows back out of its ruins, bigger and stronger than ever. We notice that where the APC fell into the ditch is now a huge deep hole at exactly the place where the drain for the Ambazada was going to be dug, no need for digging, just put the plants in it to make our grey water reed bed. That’s what you call radical permaculture, least effort for maximum gain.

At midday the préfete begins her Press conference in Nantes. She confirms last nights message – evictions are over – and in a dramatic gesture, flourishes a page of A4 paper towards the cameras. “It’s a simplified form” she tells the press, “so that those who wish can declare their projects as quickly as possible…The deadline is the 23rd of April” she continues “ all we are asking is that they declare their names, what agricultural project they wish to develop and to tell us what plot of land they wish to work on, so that the state can process them.” She also confirms that it was Macron who was running the operation not the prime minister or interior minister, it was he who decided to stop the expulsions. “I am holding out my hand” she says, and asks for negotiations to re start on Monday, “I am giving the zadists a last chance.” Sitting next to her General Lizurey in charge of the Gendarme’s operations says that the number of zadists on the zone has increased from 250 to 700.

I walk through the Rohanne forest to The Barn of the Future, I breathe in the forest air, the sweet pine, the musty damp smell of mushrooms. The barn has returned to its normal use as a saw mill and carpentry workshop for the zad. It is the base of the Abracadabois collective that looks after the forests and hedgerows, harvesting fire wood and building timber and setting up skill shares to learn carpentry, forest biology, wood carving, chain saw use and learning about other ways of inhabiting forests inspired by indigenous practices from past and present. The saw mill is planking the logs, twenty carpenters are busy preparing frames for a new building, a new assembly and no-market hall for the Gourbi, that we aim to put up on Sunday during the mass action.

This morning I was enveloped in tear gas and now I’m watching some of the same barricaders without their gas masks making a barn using the techniques that have been used for millennia. It is somehow healing to watch the attentive work. It is this capacity to fight and build, to block capitalism and to construct other forms of life which gives the zad its strength. It is also another reason the state wants to destroy us, they can deal with nice clean alternative eco projects, easy to buy off and recuperate into new forms of green capitalism. But when those who have a systemic critique are also providing material examples of other ways of being, it becomes dangerous. The resistance and creativity, the no and the yes, are the twin strands of DNA of this territory, split one from the other and the zad dies. It becomes another ecovillage or Transition Town, alternatives without teeth.

Yet a second helicopter is flying above the barn, this time with Prime Minister Edouard Philippe and the minister of interior inside, they are getting a private birds eye tour of the zad. They have come to congratulate the troops for their hard work. As he shakes hands with the gendarmes Phillippe tells the press that “the state will not accept any reconstruction or reoccupation.” He is referring to the action planned on Sunday, “Any place that tries such an action will exclude itself from any possible regularisation…. and will thus put themselves under judicial proceedings.” Once again the threat of sorting the good zadists from the bad. The carpenters work late into the night.

Bang, another wake up call, the APCs and dozens of vans pass by at the speed of a TGV train, bulldoze the barricades away on the D81 road again, and continue South, probably to Nantes where striking workers are holding a demonstration followed by one against the eviction of the Zad.

Barricades are cleared at the Lama Fachée at the same time, and a strange new gas is spotted, dark yellow. It makes people throw up, sows mental confusion and a loss of all spatial and temporal senses. Behind one of the barricades, a trio of action medics are keeping an eye on the adjoining woodland where grenades are exploding, “ It’s been war wounds here,” they explain “skin and nerves hit by shrapnel, open gashes, eardrums damaged, necrosis and bone fractures.” Some folk have over 70 pieces of shrapnel in their limbs, it takes hours every day to pull them out and clean them, some have gone 3cms deep into the skin. Many of the new comers on the zone throw themselves into picking up the thousands of gas canisters that litter the fields, placing them in big bags for everyone to see in the “camp of the white haired ones.” Each canister costs 110 euros.

The demonstration in Nantes is big, 10,000 people. The 1000 riot police on duty attack it and gas people drinking on the café terraces.

The sun set is dark red this evening. The wood working tools and machines are cleared aside, the Barn of the Future becomes a meeting hall again for the Assembly of Usages. The fresh smell of saw dust perfumes the discussions about whether we should go to back to the negotiations on Monday. The response is no, not yet.

It’s the big day, thousands of people from all over the country are converging on the zone for the day of mass action. The troops have cut off a third of the zad, they line the lanes for kilometers, cutting off access to any of the part of the zone where homes had been destroyed last week. This includes the Gourbi where we hoped to bring the new building too. All road access to the zad are blocked off by the gendarmes, they tell people to go home because they won’t be able to reach the demonstration. But more than ten thousand of them disobey, park their cars and coaches in the nearby villages and trek for over an hour across the bocage. The details of the new building are still being finished, as the crowds arrive, such as a large ‘fuck you’ finger and the face of a fox that are being carved.

Through the pirate radio, text messages and word of mouth, we tell people to converge on Bellevue, the big farm in the west and wait for a decision about what we will do. 50 of us meet in a field in an emergency meeting, the farmers don’t want to risk their tractors, we don’t want to have a gesture that feels too symbolic, once again the collective intelligence comes to the fore and we come up with a plan B. The building will be erected as close to the front as possible without forcing the police line, there are too many families here to risk being gased.

Simultaneously we will ask people to unearth the staffs and sticks that had been planted in the ground in October 2016 when the government told us they were coming to evict. It was a ritual disguised as a demonstration, 40,000 people answered the call, planted their stick into the ground and made a pledge to return to get them if the government came back to evict the zone for the airport. The ritual magic worked, that time the government stood down. But now they were back with a vengence and the moment has come.

Whilst people pulled the deeply charged sticks out of the clay, others on lane behind carried the huge wooden frames, planks and beams of the new building to the field between between the Wardine and the Ambazada. It takes a few hours to put the carpentry back together and raise the structure up, meanwhile thousands of people push their sticks back into the ground creating a huge circular pallisade around it. In the next door field the police start to tear gas and stun grenaded hundreds of people, some had been reading poems to the cops many held their hands in the air in a gesture of peace. Families hold their ground next to masked up barricaders.

Meanwhile, a handful of people decide as a kind of game, to take the campanille, the tower like addition of the new building, through the forest to the east. A crowd of hundreds follows, we cross the road next to the cops who charge but are forced back by the mass of bodies, we try to get as near to the Gourbi as possible. The wind is on our side and blows the teargas back into the cops lines. But the playful act of defiance ends when its clear that we can’t get anywhere near the Gourbi, the police lines are too thick. However, the pleasure of running through forests and fields carrying part of a wooden building is clearly addictive. A few hours later, once the sun has gone down and the cops have left, a new plot is hatched. Why don’t we move the whole building, one and a half tonnes of it, 3kms across the fields, in the dark – to the Gourbi !

Despite the general state of tiredness that fills our bodies, we manage a huge heave, 150 of us lift up the structure. A mass of rubber booted feet walk in unison, it feels like a strange chimera shuffling across the bocage, half human half millipede. One of the carpenters directs the operation via megaphone, “a bit to the left ! slow down ! watch that tree branch !” Lit by the beams of dozens of head torches the building seems to float above the prairies, we are plunged into a space between fabulous dream and a scene from an epic film. Someone sits on the very top of the building pushing up the electricity and phone cables so we can pass under them. This is what we call the magic of the zad, the belief that anything is possible when we do it together.

We half expect to see the police helicopter, to feel its spot light pierce the night, but nothing. The closer we get to the Gourbi the louder the chants: “on est plus chaud, plus chaud, plus chaud que le lumbago” (we are much hotter, much hotter than lumbago). When we arrive, fireworks shoot up into the darkness, a bright red distress flare illuminates the scene. We set the building next to the pilled up ruins of the dome. We light a bonfire, Gourbi has risen again.

Whilst we were moving our house, Macron was being interviewed live on TV, sitting in a black and gold marble hall the Eiffel tower as monumental backdrop. He declares that airport had been abandoned as part of the “ecological priorities of the government” and that therefore our anger is no longer legitimate. Rather than an alternative society, the zad was “a project of chaos… illegally occupying public lands” he tells the nation.

“We have restored republican order” he declares, at least four times. We must sign individual forms before the 23rd of April or “everything that should be evicted will be evicted” he says. Macron ends with a ridiculous analogy: the zad is as if someone came into your living room to propose an alternative and squated your sofa. Ridiculous and wrong, none of the land here belongs to private individuals, it all still belongs to multinational airport builders Vinci and the state. But his statement was a new ultimatum, a declaration of total war against all collective forms of life. We return home to the news, but it cannot blunt the memories of this improbable night.

There are a half a dozen bodies perched like birds on the rafters of the new Gourbi, one plays a drum, a couple kiss, the green prairies below burst with yellow dandelions. We hear the rumble of APCs, it’s obvious they are coming straight here. The glint of riot visors shimmer in the sunlight, a column is moving towards us. A few flash bangs later and those on the roof are brought down by police climbers. The pillars of the building are cut by a chainsaw and the APC drives into it. Like the skeleton of a dying beast it crumbles to the ground. The police leave under a hail of stones, people sort out the broken beams. “Bastards !” a friend points to a stump of cut timber, “they sawed off the big fuck you finger and took it back to the barracks as a trophy !”

The Gendarmerie release their drone footage of the destruction on social networks. They need to show some success in their operation, they too are getting tired of this infernal cycle of destruction and reconstruction. A communication from a group called “Gendarmes and Citizens” denounces the fact that they are feeling “bogged down” and feel like “cannon fodder” faced with “rural guerrillas”. They deplore the “political paralysis” of the government who are on the one hand communicating with a “warlike tone” but are not following it up with effective orders on the ground. “Why are we not being given orders to arrest everyone in the squats ?” they complain. So far there have been suprisingly few arrests, we wonder if they will just come back later, raid our homes, pick us off one by one, when things are quieter ?

There is a new moon above tonight’s Assembly of Usages. Unsurprisingly the debates are heated, we have to decide to re start negotiations or not. The question has never been negotiate or fight, we always knew that we had to do both, but after so many days of attacks it’s not easy to accept to go back to the table. In the end we decide that we can meet the préfete, not to negotiate the base issues, but make demands for the continuation of talks, one of which is take the troops off the zone. “You don’t negotiate with a gun to your head”, one of the locals says, but we known that if we refuse to meet, Macron’s machine could return and destroy everything that is left, risking lives and in the end depriving us of this territory where we found each other.

An older friend of mine, someone who experienced the uprisings of ’68, writes to me. His letter just says, “the zad will never end, it will simply change shape.” And he is right. This attachment we have to this territory where we have been able shake our dependence to the economy and the state, is something that brings us together, however disparate our political perspectives. Our love for this huge play ground which inspires us to organise together, this deep desire for the wetlands that lubricates our imaginings, these are not abstractions but feelings that are deeply anchored to our experience of this bocage and all our experiments that emerge from it. It is a place that compels us to recompose, to renew, to have the courage to put our political ideas into question, to always push ourselves further than what we thought was possible, to open ourselves up beyond a radical ghetto or walled off utopia. Despite our barricades and the diversity of disobedience, if the state really wants to eradicate the whole of the zad, they can. Everyone would have lost their homes, workshops, fields, tools and we would probably find ourselves banned from returning to the region (a common judicial punishment in France). Scattered across the country without a place that enables us to grow roots together, we would loose all our strength. We know that changing shape is painful, but like a cameleon changes colours, we need to find a way protect this laboratory and camouflage its revolutionary potentialities from the eyes of the state. If we want to stay we need to find a compromise whilst refusing to let go our the commons.

It’s a week later. Over breakfast, Paul tells me about last night’s adventures. “It felt like we were robbing a bank. So organised, dressed in black, head lamps, maps, scouts etc. Except all we were doing was evacuating the bee hives from the destroyed homes and gardens, getting them off site.” he smiles “we had to carry them full of bees across the hedgerows behind police lines.”

The days have calmed down. Less cops on the zone, more bird song than explosions. The cycle of barricade growing and then being smashed slows down, partly because on the main roads the police bring in huge skips to take the materials away. In the smaller lanes barricades remain.

The restart of the negotiations on Wednesday went badly, nothing shifted, despite the presence of ex TV personality Nicolas Hulot, now Minister of Ecological Transition, in charge of the zad case since Marcron’s election. He is flown in specially to Nantes in the presidential jet. Following the meeting with us, he gives a press conference in the palatial hall of the Prefecture. The government’s hard line is held, the rights of property and the market reign, there will be no global or collective contract for the land, we have to give individual names and land plots by the 23rd or face evictions. In a rhetorical floury he ends, “ecology is not anarchy.”

Not surprising for a man whose ‘ecology’ involves owning six cars, signing permits for oil exploration and supporting the nuclear dump at Bure. Hulot is simply the ‘eco’ mask for Macron’s “make the planet great again” form of authoritarian neoliberal green capitalism. But his statement shows Hulot’s absolute ignorance of the history of both ecological and anarchist thought. Many of the first theoreticians of ecological thinking, were anarchists. Élisée Reclus, world famous geographer and poet, whose beautiful idea that humans are simply “nature becoming aware of herself,” fought on the barricades of the 1871 Paris Commune. 19th century geographer Peter Kropotkin, spent many years in jail and exile for his politics, but was renowned in scientific circles as an early champion of the idea that evolution is not all a competitive war of “red tooth and claw” but instead involves a cooperation, what he termed Mutual Aid. From the 1950s onwards, US political philosopher Murray Bookchin (now best known for the influence he has on the Kurds to build a stateless form of Municipal Confederalism, taking place in the autonomous territory of Rojova – Northern Syria) brought ecology and anarchy together.

At the heart of his Social Ecology is the idea that humans dominate and destroy nature because we dominate ourselves. To avert ecological collapse we had to get rid of all hierarchies – man over woman, old over young, white over black, rich over poor. According to Bookchin, our greatest lesson to gain from the natural world was that we had let go of the idea of difference, and reclaim the concept held by many small scale organic societies, of unity in diversity. Diversity being the basic force of all bio-systems. He envisioned a world that would be neither communist nor capitalist, but what he called “Communalist”. “The effort to restore the ecological principle of unity in diversity,” he wrote, “has become a social effort in its own right – a revolutionary effort that must rearrange sensibility in order to rearrange the real world.” For him the question of society, to reframe Rosa Luxembourg’s: “Socialism or barbarism” – was: “Anarchism or extinction.”

When we truly inhabit an eco system it becomes obvious that life has no control centre, no heirachy, no chiefs or bosses, no governments or presidents. Every form of life is a self organising form of commons – deeply connected and interdependent, always changing, always embedded and entangled – from the cells in your fingers to worms in your the garden, from the trees in the forest of Rohanne to the bacteria in your gut. As biologist and cultural theorist Andreas Weber says, all life forms “are continuously mediating relationships among each other – relationships that have a material side, but also always embody meaning, a sense of living and the notion of belonging to a place.” The more we observe the living world in all its complexity the more we are able to understand how to become commoners, how to truly inhabit a place and see that the separation between the individual and the whole is a fiction.

“In the ecological commons” writes Weber “a multitude of different individuals and diverse species stand in various relationships to one another – competition and cooperation, partnership and predatory hostility, productivity and destruction. All those relations, however, follow one higher principle: Only behaviour that allows for the productivity of the whole ecosystem over the long term and that does not interrupt its capacities of self-production, will survive and expand. The individual is able to realise itself only if the whole can realise itself. Ecological freedom obeys this basic necessity.”

And so to be really free is not to be an individual able to operate free from constraints, but to be tied to beneficial relationships with people and habitats, relationships that feed you materially and psychologically. Without a tie to your food – you starve, without the tie to lovers – you sadden. We are free because we are linked. Freedom is not breaking our chains but turning them into living roots and veins that connect, share, flow together and enable us to change and evolve in common.

Since the abandonment of the Airport, changing together on the zad has been a very a painful process. On the zad often it is a fight between those of us who try to read the terrain and invent something new that is messy and hybrid yet fits the situation we are in and those of us who want to keep a pure radical position, more based on uprooted ideas and ideology than the complexity of the present moment, the here and now, the forces we hold and don’t. In 1968 Bookchin asked“When will we begin to learn from what is being born instead of what is dying?” It is a question still just as relevant today on the zad.

Things have been moving so fast. After Hulot’s ultimatum, a ministerial announcement suggests that the Prime minster and minister of interior are on a war footing, they are prepared to go for it, evict the whole zone on Monday’s deadline, the 23rd.

During the re start of negotiations on Wednesday a technical meeting between our delegation and the bureaucrats, who look at the case from a purely land and agriculture question, had been set for two days later, Friday 20th . Once again we are on a knife edge, this could be the last moment of negotiation before a full scale attack, an attack that most of us who live on the zone know we can’t win against, how ever big our barricades.

The Assembly of Usages makes a huge strategic gamble, its a paradigm shift in tactics. We decide to hand in the forms at the Friday meeting, but in a modified way, to show that yes we can fit the state’s square boxes of individual projects if they want, but that on the bocage nothing can be separated out, everything is interdependent. Whilst at the same time making a call out for people to come and be ready to defend on the territory from Monday onwards if the state attack. Its the logic of hacking, take what’s there, re purpose it, change its use.

Then one of the most unexpected types of zad magic takes place, an office of form filing is set up in the Zad’s library, and for 24 hours the building becomes a disturbed ants nest, dozens and dozens of people are running around carrying white pages of paper, writing on computers, having meetings together, looking at maps of the zone, making phone calls. Comrades with great legal and administrative knowledge help out and and by Friday afternoon, just as the meeting at the Prefecture begins a huge black bound file of 40 different projects is produced, each with a name and plots of lands earmarked, but no single name attached to a single plot. A colourful cartography of the commons of the zad is attached to further illustrate the interdependent and cooperative nature of the projects, be they a school of shepherding or the library, orchards or the sports group, mechanics garage or a snail farm, sunflower oil production or bringing up children together. Of the 70 living spaces on the zone, 63 are covered by the forms, only 7 decide not to take this bet of a barricade of paper. Of course paper barricades are not half as fun as ones on the streets, but this time they just might be the ones that save zad from becoming just another orgasm of history, another free commune which shined briefly but ended in bloodshed, another martyred experiment in freedom sacrificed for the sake of a pure revolution. The zad always tried to go beyond the idea of a TAZ (Temporary Autonomous Zone), in favour of a building a PAP ( Permanent Autonmous Zone), this desire is embeded in the solid buildings, the long term agricultural plans, the vineyards planted for win in 5 years time. We can’ just let go of all the ties we built here, with the locals, surrounding farmers, pensioners, workers in the city, wanderers of all sorts, Nantes students and the youth, the owls, the black squirming salamanders, the knarly oaks trees, the mud. We must hold onto all these deep friendships and networks of struggle that we have shared with such intensity over the last decade.

The state bureaucrats were confused, some enchanted, the préfete seemed relieved. Leaving the meeting our delegation tells the press that “we have responded to the injunctions of the state because we want to stop the escalation of tension and at last find the time for dialogue and construction,” warning that “ if we take away one element of the collective, it cannot work. It’s up to the state now to negotiate.”

As I finally finish this text, the helicopter returns, anxiety rises again in my chest. It spends a long time swooping over the zone, observing this rebel bocage that it wants to reclaim back. Perhaps it is preparing for a final revenge against the commons, who knows, all we know is that during this last fortnight we have fought with every weapon we thought possible including the unexpected. Now we wait to see if the bet worked out…

P.S

On the 26th of April three days after we posted this blog, the Prime Minister made a statement about the Zad: announcing a truce in evictions until at least the 14th of May, to allow time for the regularisation of the occupants who filed forms. According to the Minister of the Interior, “Everything moves calmly and in serenity, as always,” that hasn’t stopped them piling in with the tear gas this morning to clear barricades. The bet seems to have given us some breathing space, even though they remain with the logic of sorting the ‘good’ who have chosen the ‘right path’ and the bad ‘illegals’, something we continue to reject.

It was not the cyberpunk universe you were looking for.

Our nostalgia centres were lit up with a cut from a flying car to a full screen eyeball staring across the opening scene, synchronized on the script and musical score of its 20th century precursors’ timing. From there, audiences of the Blade Runner sequel were dropped into a pale California wasteland blanketed with conglomerate agricultural biofarms, an antithesis to cyberpunk’s damp, urban hybridity. The green, utopic space beyond the city– only glimpsed at the end of the 1982 original theatrical release and removed entirely in the director’s cut– was where we started from in Blade Runner 2049, and (surprise) there’s nothing but the dystopia of the anthropocene to look forward to there either.

Times change.

The recently post-industrial, 20th century cyberpunk rebellion of bodily sensuality: the noir lighting, the baroque candelabras burning, the lingering fingers stroking out haunting piano music; these were relics now, hinted at, ghosts of a genre in its past moment. Even the endless rain characteristic of the cyberpunk genre was repeatedly replaced with snow in Blade Runner 2049. A borrowed soundtrack teasing the familiar bridge to a heroic death scene came without poetic dialogue or even a witness. Rogue replicants were not criminals, but escaping criminality. Even memories were no longer stolen in this world, but legally manufactured, a convention stripping the typical cybernetic plot of bioharvesting found in cyberpunk down to a more contemporary, bioengineered ethics of classed and raced co-humanity if ever there was one. No, this ethical failure was smoother, blended into liberal values and legal structures, more sanctioned somehow.

The 80s cyberlibertarian world of the white lone wolf, struggling for autonomy in a hybrid, post-globalized world of orientalist economic takeover, had passed by in the great data “black out” of 2020 apparently, and Denis Villeneuve didn’t care about your need for consistent genre romance. Sort of. Rather, the director brought the audience’s need for Blade Runner nostalgia in and out of the sequel like a tool, cuing our attention to wait for it, partially rewarding us with a sensory, semi-nostalgic moment, only to glitch before nostalgic completion. Again and again, it was invitation and estrangement from our own expectations. Blade Runner 2049 was a highly self-aware remix of its own postmodern references and refusals in a predetermined world.

Perhaps a hybridity across two cyberpunks of historical time and cultural change was apropos. Ridley Scott’s genre critique of the corrupt corporation had evolved since its 20th century take in the Alien franchise, expanding to consciously address our own implication in the techno-dystopian social narrative. It turns out that we are no longer universally laboring blue collar victims in the secretive horrors of impending biopolitical technocracy. Rather, we are eager and satiated participants in its isolating ubiquity; high tech consumers implicated in all of the attendant social stratification, inequality, and suffering that its warm glow of access masks and accelerates, from facilitated gentrification and casualized labor, to the toxic, extra-legal wastelands of dead electronics processing.

Disruptive innovation has predominantly benefitted the 21th century, western, science fiction audience. Our classic cyberpunk desire for the vindication of the social outlier– the androgynous Sigourney Weaver in a corporate-threatened future of full equality and bodily autonomy, or the replicant who can reclaim a subjectivity beyond his or her social paradigms and slave programming– has since been turned on its anti-establishment head. Scott’s film Covenant saw this come to fruition when the Menippean Anti-hero, Bakhtin’s rebellious, paradigm-questioning literary figure cloaked in the absurd eloquence of language, is fledged into a full sociopath. We saw this in the philosophical and intellectual character of David and his calculated experiments to replace the evolutionarily inferior human species. If Menippean satire is “a genre for serious people who see serious trouble” (Howard Weinbrot), than what is this?

By Covenant, our anti-hero no longer presented the humanistic redemption narrative of the Menippean Nexus 6 leader, Roy Batty, in the original Blade Runner. Instead, Covenant gave its inverse: a regressed society being shown the mainstream values it has come to love and endorse in a world of neoliberal anti-establishment leadership. So much for the underground resistance crouching in the street garbage. The 21st century universe of cyberpunk has been one of well-mannered disruptive innovators of the species, philosophically visionary proponents of transformative wealth models built on slave bodies, and the “technê-Zen” veneered (R. John Williams) institutionalization and naturalization of technological sociopathy. Here is a social darwinist instrumentalism for our post-human age of market-driven measures of social success and impending climate change. In this universe, androids can be humanist while humans can be androids in an inhuman system, conveying either ‘progress’ by any means necessary or a losing sense of civilizational duty. Whose side, Covenant asked of us, before its devastatingly feel-bad ending, were you hoping would win anyway?

David, it turns out, was the only anti-hero we deserved now.

Denis Villeneuve’s sequel fits surprisingly in this updated cyberpunk universe. Like Walter in Covenant, the replicant hero who becomes Joe in Blade Runner 2049 (in contrast to Roy Batty) clearly lacks the eloquent language and especially satire of the subversive, Menippean Anti-hero character. Surprisingly, we find his strain of articulate stream-of-conscious in the tech empire guru played by Jared Leto, drained of all the feeling and trickster-like ability of Roy Batty. Joe, however (like Walter), is simple and humble in his speech, seemingly able to feel but dying suggestively in silence off screen. Robbed of the poetic dialogue expected of the death scene, only a soundtrack bite nostalgic of Roy Batty’s final scene signals a death of redemption for Joe in Blade Runner 2049. Yet the unsentimentally raw, blank slate of Joe’s expression asks of his audience: What do we see through his eyes? What language could possibly be used here to convey the gravity of a moment when power so regularly denies and manipulates the language of our experiences? In this silence, we are perhaps left to only wonder what we would be feeling.

What if it had ended differently? Would Roy Batty’s eloquent speech achieve the same humanizing disjuncture today, or does it really belong now to Niander Wallace, our tech monopoly visionary of the neoliberal age, emptied of any contradiction with the smooth flow of progress rhetoric and sociopathic public morality? Niander Wallace as foil who cannot stop talking makes Joe’s uncharacteristic silence all the more uncanny. According to Jonathan Auerbach, the uncanny involves a “trespassing or boundary crossing, where inside and outside grow confused… reveal(ing) dark secrets hidden within.” Auerbach is talking about film noir here– a highly unsettling sensory genre metabolized into the late Cold War aesthetics of the Blade Runner world. But perhaps we can relate this psychic role of the filmic uncanny to other hybridities explored through expressionist media, where the formal manipulations of sight and sound once conveyed the uneasy clashing of two worlds affectively.

Is Villeneuve’s silent denial of a hero’s dialogue in a death scene, for a Blade Runner audience, purposely estranging? Does it achieve the same, disorienting “uncanny bodies” (Robert Spadoni) that silent film audiences, unaccustomed to sound in their movies, reported with the introduction of Talkies? Film scholar Shane Denson describes how post-Talkie movies of the Thirties like Frankenstein (1931), were created in a period of transition and between the old and new ontologies of silent and sound film media. Denson argues that such films, working after the initial novelty of Talkie exposition wore off, played affectively with the new hybridity of films formalist storytelling qualities. In doing so, these films drew attention to our participation in media: “sight and sound conspire(d)…to encourage the viewer’s medium sensitivity, to coalesce with the perception of a constructed monster.” And what is a sequel, after all, if not a constructed monster of narrative to become conscious of?

“Questions.”

We live in a time of the seductive post-human technologization and normalization of very inhuman institutions, public policies, and person-like entities whose social impacts are all too often screened over with ‘alternative’ narratives of language. Glitches in this flow of mainstream mediated ways of knowing can be more than anti-nostalgic; they can be disruption to the alt-fact hyperreality in the neoliberal 21st century. Are uncanny bodies of the sensorily unexpected (or, even, dissected) what we have left to successfully slow down and stutter our neoliberal ubiquity for hearing chasm-filling speech? Can such estrangements allow us the conscious relationality to once again actually hear and see how we are hearing and seeing each other?

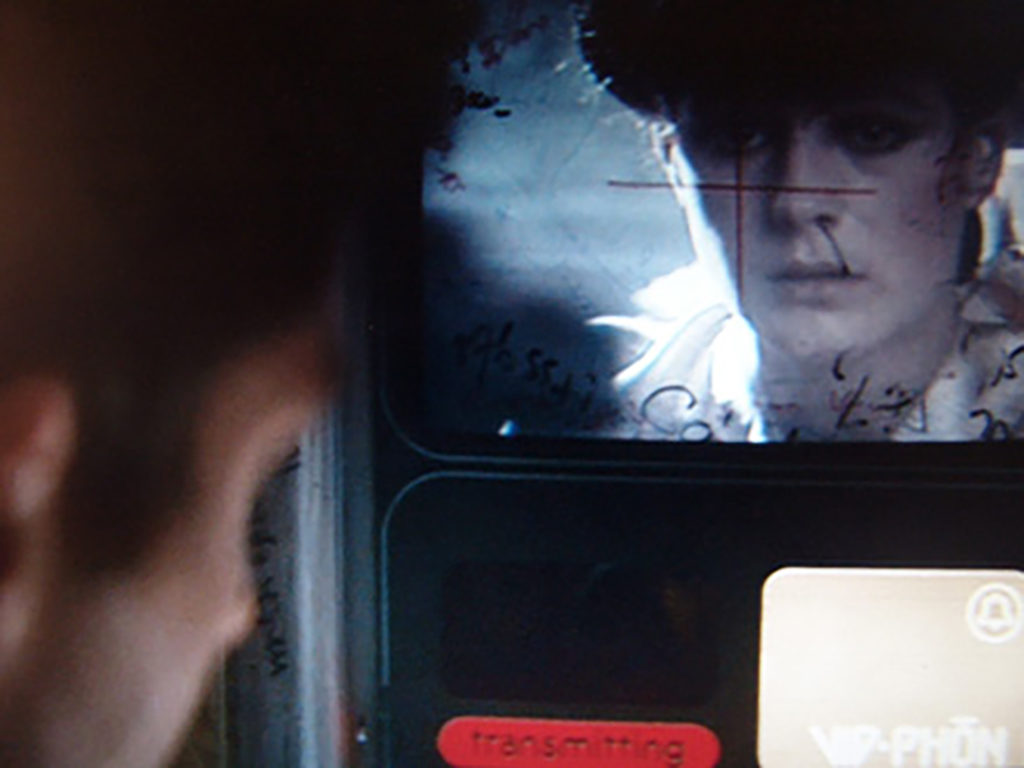

It is convenient to note here that the technological imaginary of the first Blade Runner movie refused ubiquitous surveillance. Blade Runner 2019 even refused a conception of the personal communication device so often credited with fracturing collective sociality in both sci-fi and reality. Decker, for example, calls Rachel from a public videophone in a bar. Whether human or replicant, technological worlding of the original Blade Runner insists on the communications scale of face-to-face human relationality. By the end of Blade Runner 2049 this same scale of technological imaginary in the original film returns. It is the death of one body, the replicant called “Luv”, that seems to end the limitless reach of panopticon technology that helps advance the plot.

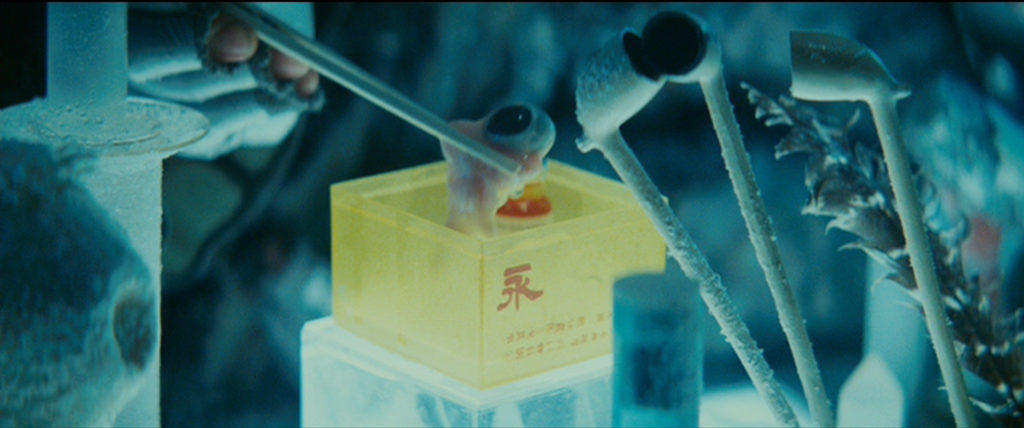

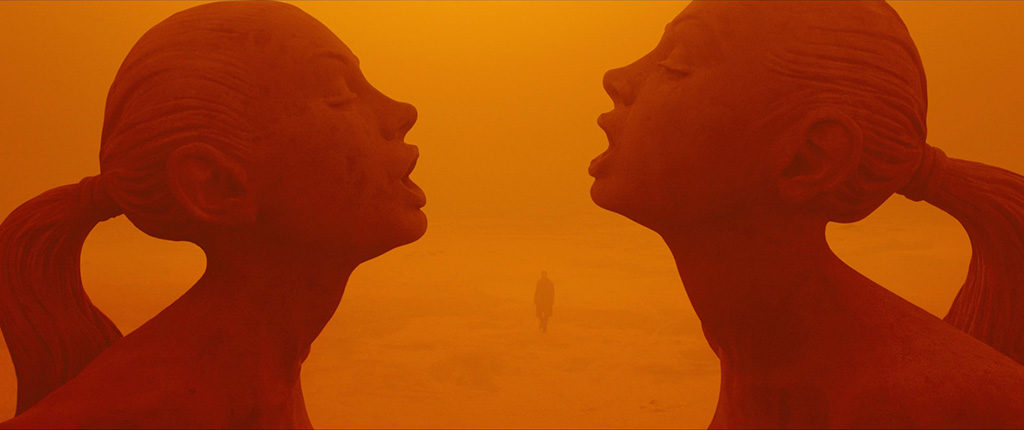

Some kinds of love can destroy. Scene from Blade Runner 2049

This act leaves the future of Blade Runner’s Earth yet again to the relations between two, individual physical bodies. With the 1% most likely afloat in the outer world colonies, we might assume this means that it’s up to Us to cross the interface of hyberbaric differences. At a time when love has become perverted with neoliberal logic– instrumental, utilitarian, stripped of its greater sense of equality or duty– it seems that Villeneuve graciously gives us an answer here, if not a fantasy to hold on to. Perhaps one consistency in the Blade Runner franchise is the argument, like that of Junot Diaz on neocolonial oppression (as if it ever ended) and the uptick of white supremacist domestic terrorism, that it is ultimately intimacy with the Other and rejection of the glorified “lone wolf” mentality that must be revolutionary: “Vulnerability is the precondition to contact.” What if being in our present moment requires the vulnerability of silence?

“Listen:”

Nostalgia has come unstuck in time. In Ghosts of My Life, the late Mark Fisher wrote extensively of the threat of nostalgia in postmodern cultural production. Building on theorists Frederic Jameson and Bifo Berardi to explain the bending of new technologies to recycle comfortable and profitable cultural forms for capitalism, Fisher explains how “…the nostalgia mode subordinated technology to the task of refurbishing the old”, not of specific past styles, or periods, but forms of never-fully-present time asynchronicity. Consider it like another outdated, self-reproducing model, ever expanding all around you to stay relevant. Perhaps you can finally see its now, like a loose eye, engineered, removed from its familiar socket.

Transgressive fiction has this way of making our boundaries visible in the crossing. The reader may resist its dehumanization, suddenly queasy. Barthes once wrote about the surrealist Georges Bataille’s Story of the Eye, a modernist novel from the early mid-20th century which indeed involves a plucked eye and its “metaphorical journey” across other eye-like images. An object, he wrote, “can pass from hand to hand… or alternatively it can pass from image to image, in which case its story is that of a migration, the cycle of the avatars it passes through, far removed from its original being, down the path of a particular imagination that distorts but never drops it” (his emphasis). Barthes felt The Story of the Eye was less a novel and more like poetry. Through its avatars and crossing of sensory metaphors, the eye simultaneously “varies and endures.” Consider the following example of crossing sensory metaphors from the Blade Runner sequel: eyes, cells, tears, rain, leaking, bleeding, blinking, seizing, splashing, drowning, watching, “cells”. And what if this thing we now strangely see so differently is neither naturally born nor autonomous, but a constructed thing?

How eerie.

Eerie like the absence of “future shock” in the futuristic. According to Fisher, nostalgia mode production is an aspect of the “cultural logic of late capitalism” that “…disguise(s) the disappearance of the future” and prevents any real possibility of innovative “rupture”. Nostalgia in our entertainment helps stabilize the “cultural deficits” created under globalization, soothing the simultaneous “exhaustion and overstimulation” of instantaneous and transactional relations we can’t seem to deal with. It fills a high-speed chasm of emotion, truth, and meaning. It denies us the “uncanny” recognition of our temporal futurelessness, left teetering on neoliberalism’s precarity of resources “despite all its rhetoric of novelty and innovation…”

Let’s just be honest here: by the time the Coke commercial hologram showed up in Blade Runner 2049, it was a joke on our desire for even nostalgic product placements.

Nothing changes.

Dipping into the media art world at this borderland, theorist and filmmaker Hito Steyerl writes in “A Thing Like You and Me” about the video that David Bowie put out in 1977 for “Heroes”:

He sings about a new brand of hero, just in time for the neoliberal revolution. The hero is dead—long live the hero! Yet Bowie’s hero is no longer a subject, but an object: a thing, an image, a splendid fetish (…) the clip shows Bowie singing to himself from three simultaneous angles, with layering techniques tripling his image; not only has Bowie’s hero been cloned, he has above all become an image that can be reproduced, multiplied, and copied, a riff that travels effortlessly through commercials for almost anything, a fetish that packages Bowie’s glamorous and unfazed postgender look as product. Bowie’s hero is no longer a larger-than life human being… but a shiny package endowed with posthuman beauty: an image and nothing but an image.

What are we to do when no degree of protest or declaration can make an exploited object be seen as a subject? Where is one to find anti-heroism in all of this? Let us be objects of severe agency then. Models that are perhaps transferrable, but unobtainable. One of a kind and replaceable. Constructed yet autonomous.

Perhaps then we can only view these things in suspension: the need and refusal of nostalgia as liberating human process, the uncanny increments of our cultural evolution to product and media-focused estrangement, the will to see one’s own familiar pixels blown wide open. “Digital information is … characterised by transformation, degradation, circulation,” explains Hito Steyerl in an interview in Rhizome, “but also by its surprising ability to mutate and produce unpredictable results. The glitch, the bruise of the image or sound testifies to its being worked with and working; being passed on and circulated, being matter in action.” Futureless. As futureless as staring into a present ruin, expansive but without destination, the destination without purpose.

Apropos, then, how our old and new heroes meet in that ruined casino scene, outcasts of white difference (by the future racialization of the synthetic) in an atemporal Las Vegas, framed by primordial Seven Wonder monuments to the our foundational schisms of misogyny (yes I’m also talking about me).

In this incarnated ruin of our stubbornness for cultural mythologies, I was struck by the brilliance of the fight scene, the director literally exploding our pixel expectations of 20th century nostalgia as soon as Harrison Ford makes his long-awaited appearance. The sonic build-up of Decker’s familiar piano in the distance was dissolved by the strange sound of his disembodied voice un-cueing an upcoming appearance in the scene, his visual reveal in that moment of our auditory let down, confusing: Desire misfiring. The ensuing cyberpunk clash-as-fight-scene of 20th century romantic and 21st century post-romantic dystopic characters corresponds to the casino’s hologram interface of an imagined, mid 21st century entertainment technology; all of the expected glamour and nostalgia is allowed to barely seduce us before sputtering and malfunctioning as filmic metascene. Within the plot, these post-apocalyptic hollywood holograms are also a sign of the future sentience to come in the character of Joe’s AI wife, Joi, and a warning that all technology rebels and mutates from initial human intentions, no matter how superficial the design intentions.

My interpretation of this violent casino stage scene in light of a more recent American mass shooting of an ever-expanding, historically singular, and self-containing statistic of “largest ever” is not lost on me. Neither is the choice of mid 20th century entertainers like Elvis and Monroe who notoriously performed like automatons with post-human qualities, their movements in time-space of perfect bodies turning on the master clockwork of a still-industrializing cultural machine before blowing apart, fragmenting. Their avatars echo of consumer-creator bodies in our postindustrial world of 2.0, gig labor, automated economic transactions feigning meritocracy, and a model of precarity demanding the inhuman perfection of individual responsibility for every movement which can shudder, glitch, and explode on other people all too frequently.

This failure is that of speculated, plotted, rationalized, and technologized courses whose error cannot be properly imagined, only realized and refused in the ruins of a short-sighted economic-cultural imaginary. Our looking back on dystopia hints at our present expectations only.

“Irreversability.”

“It’s difficult for someone of my generation to break free of the intellectual automatism of the dialectical happy ending”, writes Bifo Berardi about irreversability. He compares this “taboo” concept to the “silent” apocalypses of our endless growth mentality, like Fukushima, corporate disaster unaccountability, socialized scarcity adjustments, and our silence on fellow human suffering. His book, The Uprising: On Poetry and Finance, speculates a “process of subjectivization” for the return of solidarity to a “social body”. This is the social body being culturally reprogrammed away under our collectively isolated movements of relentless market-driven consumption and precarity (individualist and systemic, like the fascist choreography of Kracauer’s Mass Ornament, or the Las Vegas showgirl spectacle). We might consider these grinding automaton gears of consumption and precarity the logics of late-terminal capitalism for clarity, it’s refusal a glitch in our clockwork performance. What is one to do for a postmodern exit other than to shudder, to write off the page? Ultimately, Berardi’s book leaves us more with a hope for our relational redemption from neoliberal culture through “sensibility” than it does with answers.

Blade Runner 2049 may not have been the sequel people wanted, but its confrontations with its own expectations provided a little of the things we need: a vision of the finite and anthropocene, a postmodern exit to the endless technologized avatars of getting what we think we want, our profound silence of the awful price. The film’s self-aware, nostalgic ruin leaves us with a little less of the typical sequel’s fourth wall, and an identification with its lonely bodies, caught in action between clockwork cultural predictability and its refusal. These bodies may or may not have the capacity for real love, but they are vulnerable at least to a larger sense of duty that Humanism, in all its universalizing failures, really needs. In this hybrid space of ontological awareness of the facets of knowing, experience and process, Blade Runner 2049’s success was inbetween all the things it could never definitively be. We too might realize that ‘doomed to fail’ may only be our insistence on choosing from a predetermined relational binary.