This interview was originally printed in Artists Re:Thinking the Blockchain published in partnership with Torque Editions in 2017.

Marc Garrett: One of many interesting and experimental things about the album Platform, released with Holly Herndon in 2015, is the decision to break away from the perspective of singular genius, and involve a variety of collaborators. This included artist Spencer Longo, Claire Tolan (of Tactical Tech), and Dutch design studio Metahaven. On the 4AD press release page it says that it ‘underscores the need for new fantasies and strategic collective action.’ Under the name of Holly Herndon, along with Holly, you all became a kind of cooperative, collective construction. What inspired you and Holly to explore what could be seen as a decentralized body, or assemblage of individuals as a collective? Or how would you describe your working identity and the importance of this move?

MD: To put it in pretty boring terms, it has become a core part of our mission to be pretty candid about what we do. Holly had been making albums and touring by herself, and then during the early experiments that later became Platform (Chorus and Home) we had begun working together, as we were occupying this tiny apartment in San Francisco, and I was working on this weird net concrete stuff in one room, and Holly was writing for voice in the other, and I think both of us picked up from the ambient sound that the two worked really well together! For the Chorus video we had seen the work of the Japanese artist Akihiko Taniguchi, and really enjoyed the collaborative process of putting that video together, and so then sought out Metahaven, who we’d been in touch with for some time out of aligned interests. Basically most art production at a certain high level is collaborative, and I think it’s just part of our idealistic view on the world that this be transparent and celebrated. Beyond that, when we were coming up with the vision for Platform it also felt very necessary as a political gesture to make a point of the project being aligned with certain political interests, and a politicized way of working and acknowledging others. Working this way has changed my life, and made everything more fun and exciting without diminishing the importance of any individual contributions. It makes for better results, I feel, better general feeling, and also creates these very tangible collaborative connections between fields. It’s also just an interesting experiment to run in music when it feels like so many sonic experiments have been done to death – I’m personally interested in how decentralized practices, collaboration and connectivity, can change the construction and dissemination of music, and ultimately it’s power to be a force in the world.

HH: It sometimes feels like our society is ‘every person for themselves’. We promote hyper individualism at the cost of the planet and social health, and the music industry largely parrots this mentality. We realized how problematic this is, and if we are going to be true to ourselves, then the practice should reflect that concern. It’s been a learning curve for me; learning to not control every single aspect (I tend to micromanage), to hear other opinions, to let go, and not feel threatened if someone else’s idea is better than my own. Releasing my debut album solo was an important step in building my confidence, however ultimately the work itself is the most important, and not the ego. Not to mention that we spend a lot of time on computers, which can be lonely, so working with other people helps us to unplug and see the world around us a little more.

MG: In a world that traditionally, economically and politically, supports the values of individuality above community, or peer to peer collaboration. How did the audience, the music industry, and others in the world (presuming they have) come to terms with this adventurous, creative intention?

HH: It was varied, but overwhelmingly positive. When we were doing press around the record, it was difficult to get some journalists to write about the other artists and thinkers that I was collaborating with, or even just referencing. Those that understood the gesture really embraced the idea, and that successfully provided a platform to highlight everyone’s work.

There are a few industry complications; for example, the project is released under my birth name, so in some ways I am still at the centre of the orbit, which is a problematic professional necessity, but also helps somehow. We used the idea of the Trojan Horse a lot, as in a way my easily understood singular presence served as a gateway into this whole other universe of people. It’s a balancing act, as in various different scenarios you feel different expectations as to what the industry wants; on a pop level they want a simple narrative of my face, and tend to focus on often mundane characteristics such as my gender and education. On other levels you see that the experiment has opened up a different narrative potential, where people’s interest in the record and it’s cast forks off into the direction of their choosing.

It’s really noticeable live, where the audiences have been really supportive. After the shows you experience all kinds of people who come along, hanging out with different people who were on stage – Mat has his own audience somehow, and the same with Colin Self, who often tours with us. As a result of opening up the process and allowing the full breadth of interests and approaches to shine through a little more than is standard, at different shows we have people come up to talk to us about the music, or nerd out about cryptocurrencies and ICO’s, or Chelsea Manning. It feels meaningful, and gratifying for that. We always address the location of the show, whether through the visual or sound, and try to always be alert and responsive. It’s a special privilege to share that time with people, and I think that the concept comes across quite effectively in a live situation as each individual serves a very different purpose in constructing the collective experience.

MD: I think that Platform was received really well. Holly opening up her practice didn’t diminish her signature on the artworks, and I think that it has really won a lot of people over. I think you can feel at our shows that we have a greater principle to what we do, and I think it has maybe made a lot of space for people to conceive of their own experiments and maybe not be concerned at how being ambitious on a conceptual level will affect the ability for the art to travel in the world. Naturally there is also a throttling effect within aspects of the creative industry, where maybe they didn’t want to deal with the bigger ideas around the record, however I feel that the music is strong enough to kind of live in those circles without knowing the story behind it. Overall I think people were refreshed and encouraged by the idea, and transparency of the whole thing. For us now it is a way of being. In my mind, there is more room for individuality to shine when you can guarantee that someone’s work and ideas will be respected and celebrated. The canon of artistic history has omitted so many people’s ideas and contributions for the purpose of having a simpler market narrative, and yet we live in a time when people can and want to dig deeper, and perhaps have a greater capacity for complexity of information – so we want to try and harness that for something positive. Particularly given our interests in subcultural music history, software, crypto etc. there is really no other option but to put the community first. Without community literally none of this exists. Zero. All of our talents and ideas have been incubated in community environments, so channelling that legacy is important.

MG: On Platform you released the track called DAO. I am always interested in shifts between the use of technologies as metaphor and as tools that change practice. So, what was interesting to you about Decentralized Autonomous Organizations (DAOs)?

MD: I’ll let Holly talk more about where DAO came from, with the telematic performance work she was doing at Stanford. Regarding the blockchain, I’ve been developing my own decentralized publishing framework for the past few years, that shares a lot of the same principles as the Ethereum logic, and I’m looking to have it interact with the blockchain in its next iteration. A lot of the spirit behind the crypto community is so synonymous with the models of collectivity we have already been exploring in our work that it’s the logical next step. I’m particularly interested in what this architectural/infrastructural new capacity can mean for the medium of music itself. With Saga you have this whole other performative dimension added to media with the ability to version work, fork it, and have it perform in real time to it’s surroundings online, which I think is a whole other proposition for the medium very much worth exploring. It’s also fascinating regarding the question of attribution and collaboration, as we have grown to understand that the web as it stands currently is very much designed to privilege those who appropriate and curate others creative work and ideas for free – mirroring greater society, it is a winner takes all environment. I want systems of virtuous attribution that do not consolidate the DRM era of copyright takedowns, but instead build markets and new interactions around collaboration, augmentation and live interaction. There is so much more that could be done, and a lot of the blockchain tech emerging offers clues as to how we can get there quickly. There are also a lot of old ideas masquerading as something shiny and new, so you kind of have to read the small print to distinguish what is a genuinely new proposition, but it is our job as members of marginal communities to educate ourselves and anticipate the best options.

HH: DAO came out of a piece that I wrote called Crossing the Interface, with a libretto by Reza Negarestani. The piece was my first venture into telematic performance, where a soprano (Amanda DeBoer) was in another geographic location, but the audience could hear her physical body moving throughout the space using ambisonics. I wanted her to be hyper present, and physically super human, moving in ways impossible to a human body, to be able to be in multiple places in the room at once, as eventually her voice and her body separate, stalking the room. I was trying to find a way to make something so clearly highly mediated, feel extremely personal and embodied at the same time, which seems appropriate for the DAO concept as it exists in the world – this simultaneously complex and distributed network that is also hyper intimate and moves with collective intent.

The vocal work that Amanda delivered while workshopping that performance was really great, so I used some of those outtakes for the vocal work in DAO. With the instrumental I was simply just trying to capture an atmosphere, a heavy energy with lots of wide stereo movement. It’s also really fun to play live with Colin, because he sings the soprano line with live processing, which creates a nice contrast of heavy electronics with extremely expressive alien vocals, taking the entire gender spectrum and contorting it into a circle.

MG: Do you have any plans to formalize any part of your creative collaboration to work on the blockchain?

MD: Holly and I are starting a studio after we finish this next album to more formally develop work and devices that exist in this new frontier, as it has been so instrumental in our discussions for the past few years. I describe it as a frontier deliberately, as if we are to task ourselves with actually experimenting with our work then it feels almost like a duty to get our hands dirty in these areas. We have already started work on two new projects in this domain, but it’s hard to tell when they will be ready to show to people, and what shape they will eventually take.

MG: OK. Last question, in light of the current suppression of the spirit of humanity by despots, and the rich buying up democracy for their own ends, what part do you see artists playing in the world of blockchain, to disrupt the regurgitation of an already bankrupt system?

MD: IMHO, there are two dimensions to this. First, I encourage artists to become familiar with the language and potential of blockchain technology, as there are a lot of opportunities to attempt to re-engineer how we experience, transact and grow community in the arts outside of centralized traditional channels. Real money is being made, and there is a lot of good will amongst the crypto community who invest faith that better systems can and will be constructed using these logics.

I also encourage artists to develop some fluency around the blockchain ecosystem, for exactly the reason that there needs to be wary and critical voices guarding the community from the business-as-usual corporate crowd, who are increasingly flexing their muscles and influencing the course of its development and maturity. By getting involved early, and being vocal, there is an opportunity to intercept plans for how this next internet runs, and who ultimately it will benefit.

The best case scenario is that we can develop our own systems along the blockchain to change music and the arts for the better. Alternately, we need critical voices active within these conversations to avert the worst case scenario of power consolidating itself even further outside of the greater public awareness.

I should say that the third wild card possibility is that blockchain technology is inherently flawed and infeasible once it has been properly stress tested at scale. Irrespective, if your mandate is to be experimenting, and abreast of where things may be going, there are fewer areas of interest more dynamic and potentially transformative. It’s a lot of fun to think about.

Most households have an unsolved Rubix Cube but you can easily solve it learning a few algorithms.

Hazar Emre Tez has created Sonic Tunnel as a delightful and innovative solution to wayfinding in Finsbury Park. Come and explore the park following a sonic route that has been created using strategically placed speakers to broadcast sounds as an alternative to traditional visual signage.

Hazar Emre Tez is a musican, performer and engineer. After his master degree in Universitat Pompeu Fabra – SMC, he started his PhD in Queen Mary University of London, Media Arts and Technology. Currently, he is working on interaction and sound design, he has programming skills and is making electroacoustic music.

Start your visit on the surroundings of Furtherfield Commons – view map

Finsbury Gate – Finsbury Park

London

Furtherfield in partnership with MAT PhD programme, Queen Mary University.

Marc Garrett reviews Stefan Szczelkun’s book Agit Disco. He is an artist and author interested in culture and democracy. In the early Seventies he was fortunate to be part of the Scratch Orchestra and has since been involved with a series of artists collectives. His doctoral research into the Exploding Cinema collective was completed at the RCA in 2002. Recently his collaborative project Agit Disco was published as a Mute book in 2012. He has been on the Mute magazine editorial board since 2009, and currently working on photographic and performance projects.

“Just cause we can’t see the bars

Don’t mean we ain’t in prison.”

Kate Tempest (2009) [1]

The subtle and not so subtle domination by market interests of cultural production and dialogue denies us all access to a wide spectrum of creative expression, especially those that engage in subjects that conflict with the agendas of those in power. Agit Disco by Stefan Szczelkun combats this contemporary trend by focusing on music, politics, DIY culture, and freedom of expression. In doing so he starts to redress the lack of representation across the board for those in grass roots culture and working class lives, whose freedoms to have a voice in society are so commonly restricted.

The future does not look good for those who value cultural and social diversity; who look for a variety of activist histories and experiences to be seen and represented on their own terms. The UK government is changing university regulations so that private companies can become universities. This means tutors will end up replacing educational courses once devised with the public good in mind with modules designed for maximum profit. Luke Martell, a critic of the marketisation and privatisation of education and lecturer of Sociology at the University of Sussex, says “This will lead to a different content to education. Critical thinking is being replaced by conformity to cash. Money-spinning management and business courses are expanding and lower-income adult education is being closed down.” [2] (Martell 2013) Already, most researchers, academics and those in professional fields of practice mainly work within insider frameworks, “there is a qualitative difference between the conditions of people living in marginalized communities and those in middle-class suburbia.” [3] (Smith 2012)

The knock on effect of an unquestioning culture of compliance with the ‘free market’ is enormous. How ironic it is that the term ‘free market’ is attributed with so much value and (a presumed) logic when in actuality it constrains people’s freedoms and makes those who are already rich even richer. Because the politicians are not effected by the results personally, and because it also serves their interests, they have handed over their social responsibilities to these market systems. The neoliberal defaults that caused the financial crisis are untouched by our democratic processes. These out of reach, distant power systems are fixed towards property bias and occupy and govern our everyday experiences. How does freedom of expression fit into this and on whose terms?

“The more our physical and online experiences and spaces are occupied by the state and corporations rather than people’s own rooted needs, the more we become tied up in situations that reflect officially prescribed contexts, and not our own.”[4] (Garrett 2013)

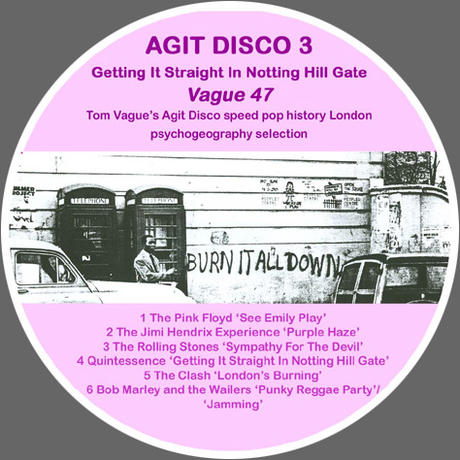

Agit Disco offers a breath of fresh air, in the fug of the developing marketisation of everything. It presents grounded examples of difference that contrast with the dominating view of entertainment systems. Published through Mute Books in 2012, it features 23 playlists put forward by 23 different writers, artist and activists. It began as a set of mixed CDs and images, each chapter includes annotations and illustrations. Its contributors are Sian Addicott, Louise Carolin, Peter Conlin, Mel Croucher, Martin Dixon, John Eden, Sarah Falloon, Simon Ford, Peter Haining, Stewart Home, Tom Jennings, DJ Krautpleaser, Roger McKinley, Micheline Mason, Tracey Moberly, Luca Paci, Room 13 – Lochyside Scotland, Howard Slater, Johnny Spencer, Stefan Szczelkun, Andy T, Neil Transpontine, and Tom Vague.

Mostly from working class backgrounds the contributors were invited to focus on politics and music, and share memories relating to what the tunes meant to them at the time. In the preface Szczelkun states, his selection of contributors comes from his own worldview and personal contacts. Anthony Iles, in his introduction says most who have contributed “are closely associated with anti-authoritarian politics and DIY culture.”[5] (Iles 2012) Contributors offer insights into the connections between their music and the politics of the time. Louise Carolin says, “When I was a teenager in the ‘80s I lived through one of the golden ages of British chart pop, listening to music that was by turns, political, danceable, challenging and entertaining. I attended CND rallies, marched against South African Apartheid, ran the feminist group at school and went to GLC-funded music festivals.”[6] (Carolin 2011)

What adds depth to Louise’s story, as with the rest of the contributions is that many readers feel connected with these histories, and I am one of them. It highlights an indigenous, working class culture and their personal struggles in a period when neoliberalism was in its early stages of world domination. To say that these are merely anecdotal or subjective would completely miss the point. It calls for an awareness and understanding about people giving an account for themselves in relation to music, politics and their social contexts on their own terms.

Just as it is important to ask contextual and critical questions of why a particular artwork is being shown at a certain venue or seen in an art magazine. It is also necessary to observe who published Agit Disco and why? It is no coincidence that it’s a Mute publication, Szczelkun has been on its editorial board since 2009, and has written various articles, reviews and interviews for Mute.

Agit Disco resonates with Mute’s dedication to DIY culture. Indeed, Mute has an excellent history in independent publishing alongside its DIY methods of production. Mute’s earliest incarnation used Financial Times’ pink paper, broadsheet printing cast offs. Later on a traditional magazine format. From 2005 onwards it moved onto its online site, and developed a publishing platform that allowed the publication of its POD (Print On Demand) magazine. [7] The design and production of Mute and its platforms have come a long way enabling a pamphlet-like production and distribution, echoing Thomas Paine’s own DIY releases of the Rights of Man.[8]

DIY Culture (and its distribution channels) offer a vital alternative to mainstream frameworks and their dominating hegemonies as a way to route around the restrictions to content, freedom of thought and free exchange. We have to contend with networked surveillance strategies initiated by corporations and state secret services. Censorship exists in many forms and recently there has been a rise of self censorship by workers and academics worried about losing their jobs if bosses see their interactions on Facebook or similar Web 2.0 social networks.[9] And the worrying antics of Britain’s GCHQ, in collaboration with America’s National Security Agency (NSA), targeting organisations such as the United Nations development programme, the UN’s children’s charity Unicef [10] reveal a greater investment in the surveillance of everyone, and the downgrading of privacy and fundamental human rights.

The credo that Anyone Can Do It reached a mass of individuals and groups not content with their assigned cultural roles as disaffected consumers watching the world go by. Like the Situationists, Punk was not merely reflecting or reinterpreting the world it was also about transforming it at an everyday level. Sadie Plant states that with the “emergence of punk in the late 70s […] lay the possibility of a threatening political response to the vacant superficiality of contemporary society.” [11] From this, a whole generation of diverse artists emerged; and through their practices they critiqued the very society they lived in, questioning authority and the authenticity of established politics, language, art, history, music and film.

Has the process of appropriating people’s civilian personas, and then replacing their social contexts with a corporate role as consumer created a more selfish world, lacking compassion for others and less interest for societal and ethical change? Ubermorgan discussed in a recent interview with Stevphen Shukaitis that people are in a state of ‘mediality’. “What we refer to as reality very often is just mediality, and also because that’s how human nature often prefers to observe reality, you know, via some media.” [12] Perhaps our constant interactions through different interfaces of proprietorial frameworks distances ourselves to what is important. In the 21st Century demonstrations and civil disobedience are policed intensively, and even though much of contemporary activism exists on-line. The frontline, or the heart of politics is still mainly a physical matter; it is still in our streets, our homes, our bodies, in our neighbourhoods and communities.

As Oxblood Ruffin a Canadian hacker and member of the hacker group Cult of the Dead Cow (cDc) and the founder/director of Hacktivismo, said “I know from personal experience that there is a big difference between street and on-line protest. I have been chased down the street by a baton-wielding police officer on horseback. Believe me, it takes a lot less courage to sit in front of the computer.” [13]

So Agit Disco reminds us that music is a vital way of both bringing people together in a space, story telling and communicating with each other, sharing what is happening with people’s lives. It is usually at the moment of censorship that we then realise how essential this freedom of expression stuff really is. For instance, nine months after Islamic militants had taken over in northern Mali they announced that all music is banned. “It’s hard to imagine, in a country that produced such internationally renowned music as Ali Farka Touré’s blues, Rokia Traoré’s soulful vocals and the Afro-pop traditions of Salif Keita. […] The armed militants sent death threats to local musicians; many were forced into exile. Live music venues were shut down, and militants set fire to guitars and drum kits. The world famous Festival in the Desert was moved to Burkina Faso, and then postponed because of the security risk.” [14] (Fernandes 2013)

In her article The Mixtape of the Revolution, Fernandes says that in Africa many rappers are “speaking boldly and openly about a political reality that was not being otherwise acknowledged, rappers hit a nerve, and their music served as a call to arms for the budding protest movements.”[15] Regarding Egypt, the rapper Mohamed el Deeb in an interview with Fernandes said, “shallow pop music and love songs got heavy airplay on the radio, but when the revolution broke out, people woke up and refused to accept shallow music with no substance.” [16] Music, politics and grass roots dissent are concrete expressions and an essential part of our collective freedoms. Alongside this, independent publishing as an alternative voice to the marketed franchises that dominate our gaze, sight, ears and minds, are needed more than ever. Yet, independent voices are being silenced and whittled down by wars, oppression and the neoliberal created financial crisis and its resulting austerity cuts.

What is to become of us if we lose our skills of discernment and slump into a homogenous consumer class, to define ourselves solely through marketed stereotypes and ideologies?

Agit Disco offers a festival of dance and dialogue for independent minded individuals and groups around the upturned burning car in the barricade against the coming zombie apocalypse.

It has been fun listening to all of the playlist contributions provided in Agit Disco. Below is my own Agit Disco playlist. You are welcome to add your own playlist in the comments section below (with links)…

Damien Dempsey – ‘Dublin Town’ (2000)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=brhO8pqTNHU

Asian Dub Foundation – ‘Modern Apprentice’ (2000)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zgtWhjaOgQ4

Dan Le Sac & Scroobius Pip – ‘Great Britain’ (2010)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YeV2cExvnMI

Kirsty MacColl – ‘Fifteen Minutes’ (2005)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MSQrH3JUQ2s

Jeffrey Lewis – ‘Do They Owe Us A Living?’ (2007)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jWU-W0SzVE0

The Pop Group – ‘Forces of oppression’ (1979)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Txzmbu6o-gg

Kieron Means – ‘I Worry For This World’ (2005)

https://play.spotify.com/track/6AI2QujkrP6B2nfIUK55lY

Robyn Archer – ‘Ballad on Approving of the World’ (1984)

https://play.spotify.com/album/3hNQY8q9sO3M0R6es2d3ka

Robyn Hitchcock – ‘Point it at Gran’ (1986)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_HFkimK9FAU

Sound of Rum – ‘End Times’ (2011)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9dWPe7Au68A

Silver bullet – ’20 Seconds to comply (final conflict)’ (1990)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=24b6pYGT9MM

Maze – ‘Color Blind (Featuring Frankie Beverly)’ (1977)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=COY4gKLwV2I

Akala – ‘Bullshit’ (2006)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mxpxpQ7j8Sg

Sarah Jones – ‘Your Revolution’ DJ Vadim (2000)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E62SZ1CmBOI

Julian Cope – ‘Soldier Blue’ (1991)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8dGOr-JpOmI

June Tabor – ‘A place called England’ (2009)

https://play.spotify.com/track/3YB6sSlLfB8kmMrrm5COKX

In the 1990s the idea of the virtual idol singer escaped from Macross Plus’s Sharon Apple and William Gibson’s Rei Toei into the cultural imagination. Blank slates for market forces and projected desires, virtual idol singers differ from Brit School drones only in that there is no meat between the pixels and the data.

Hatsune Miku is a proprietary speech synthesis program with an accompanying character whose singing the software notionally renders. Miku the software is a “Vocaloid” synthesizer using technology developed by Yamaha and the sampled voice of voice actor Saki Fujita. Released in 2007, with additional Japanese voices in 2010 and an English version in 2013, the software topped the charts in Japan on release and has led to spin off games and 3D modelling software. It’s claimed the software has been used to produce over 100,000 songs.

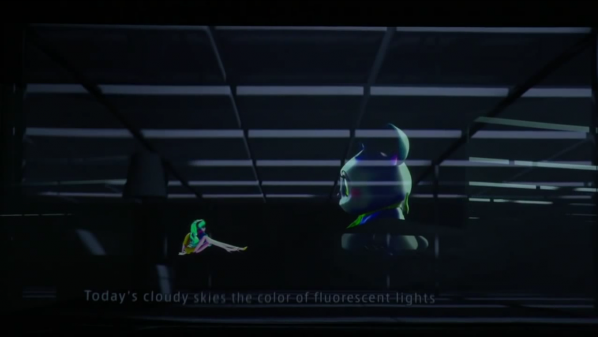

Hatsune Miku the character is a cosplayer’s dream, a sixteen year old (with a birthday rather than a birthdate) Anime young-girl with impossibly long aqua hair (there are male Vocaloids as well). She’s had a chart-topping album, “Exit Tunes Presents Vocalogenesis feat. Hatsune Miku” (2010), and started performing “live” on stage in 2009 with Peppers Ghost-style technology. She’s available as (or represented as) figurines, plushes, keychains, t-shirts, and all the other promotional materials produced for successful Anime characters, pop stars, or both. Her likeness can be licensed automatically for non-commercial use. This makes her fan-friendly, although not Free Culture, and means that fan depictions and derivations of her are widespread. The majority of “her” songs are by fans rather than commercial producers.

She is now appearing in “The End” (2013), a posthuman Opera (with clothes by a designer from artist-suing fashion company Louis Vuitton) where she takes the stage as a projection among screen-based scenery without a live orchestra or vocalists. Which means that someone programmed the software to produce synthesized vocals and someone else negotiated the rights to use the likeness of the characted commercially dressed in a particular designer’s virtual clothing. “She is now appearing” is easier to say, but like Rei Toei this is an anthropomorphised representation of the underlying data.

It’s getting rave reviews, and the music is competent, enjoyable and affecting: strings, electronica and Supercollider-sounding glitches and line noise under breathily cute synthesized vocals. The visuals are CGI with liberally applied glitch aesthetics, mostly featuring Hatsune Miku and a cute chinchilla-ish animal sitting in or falling through space. The plot is a meditation on what mortality and therefore being human can possibly mean to a virtual character. To quote the soundtrack CD booklet notes:

Miku, who has had a presentiment of her fate, talks with animal characters and degraded copies of herself to ask the age-old questions ‘what are endings?’ and ‘what is death?’.

The phantom in this particular opera is composer Keiichiro Shibuya, who appears onstage largely hidden by two smaller projection screens. As the man behind the curtain it’s tempting to read him as the male agent responsible for the opera’s female subject’s troubles. His presence onstage also threatens to make him the human subject of what is intended to be a repudiation of opera’s European anthropocentrism. But without such an anchor the performance would seem less live and perhaps become cinema rather than opera. It seems that a posthuman opera needs a human to be post.

Music production is uniquely suited to the creation of virtual characters through tools, brands and fandoms. Hatsune Miku functions as a guest vocalist, a role combining artistic talent and social presence with a well understood standing in the economics of pop. In art, Harold Cohen‘s sophistiated art-generating program AARON was licensed as a screensaver anyone could run to create art on their Windows desktop computers, but despite its human name and human-like performance, AARON is never anthopomorphised or given an image or personality by Cohen. Could a virtual artist combining software and character similar to Hatsune Miku function in the artworld or in the folk and low art of the net and the street?

The license for Hatsune Miku the character is frustratingly close to a Free Culture license. Could a free-as-in-freedom Hatsune Miku or similar character succeed? Fandom exists as an ironisation of commercial culture, appropriating mass culture in a bottom-up repurposing and personalisation of top-down forms. Without the mass culture presence of the original work, fandom has no object. Perhaps then without the alienation that fandom addresses, shared artistic forms would not resemble fandom per se.

There are precedents for this. Collaborative personalities abound in art, such as Luther or Karen Blisset. And in politics there is Anonymous. There are also existing Free Culture character like Jenny Everywhere, or even the more informally shared Jerry Cornelius. So it is possible to imagine a Free Software Hatsune Miku, but it’s less easy to imagine what need this would meet.

Unlike the idol signers of literature and television, there’s no pretence that Hatsune Miku is an artificial intelligence. But she is an artifical cultural presence, created by her audience’s use of her technical and aesthetic affordances. Like the robots in Charles Stross’s “Saturn’s Children” (2008), Miku’s notional personhood (such as it is) is defined legally. As a trademark and various rights in the software rather than as a corporation in Saturn’s Children, but legally nonetheless. Heath Bunting’s “Identity Bureau” shows how natural and legal personhood interact and can be manufactured. It’s tempting to try to apply Bunting’s techniques to software characters. If Hatsune Miku had legal personhood, would we still need a human composer onstage?

“The End” was written by that human composer, but software exists that can generate music and lyrics and to evaluate their chances of being a top 40 hit. Combining these systems with software made legal persons would close the loop and create a posthuman cultural ecosystem that would be statistically better than the human one, which I touched on here. It’s not just our jobs that the robots would have taken then. Given the place of music in the human experience they would have taken our souls.

Or the soullessness of Fordist (or Vectorialist) pop. Such a posthuman music system would exclude the human yearning and alienation that fan producer communities answer. It would be an answer without a question. Hatsune Miku is in the last analysis a totem, the products incorporating her are fetishes of the hopeful potential that pop sells back to us.

Despite “The End”, Hatsuke Miku has no expiry date and cannot jump a shuttle offworld. It’s not like she’s going to marry a fellow pop star or come tumbling out of networked 3D printers. But human beings are becoming less and less suitable subjects for the demands of cultural and economic life. In facing our mortality for us Hatsune Miku may have become more human than human.

The text of this review is licenced under the Creative Commons BY-SA 4.0 Licence.

Drake Music launches a making day to inspire the creation of more accessible musical instruments.

On Sunday 21 April Drake Music will run a hackday to create and share new instruments that break down disabling barriers to music making. Run in partnership with Furtherfield and Music Hackspace, makers will have the opportunity to work towards one of two prizes for the most innovative work.

Hacking To Make Music Accessible Day is part of Drake Music’s new R&D programme, which aims to:

As of January 2013, there are only 6 widely available solutions for accessible music making. In contrast an orchestra is made up of at least 19 instrument types; rock and pop frequently use 4 or more types; and the instruments used in world, electronic, jazz and folk music add up to a rich and diverse pallet of choice for most aspiring musicians. This disparity needs to be bridged, in particular with the development of more expressive musical instruments for those facing barriers to music making.

Hacking To Make Music Accessible is developed with and supported by Music Hackspace and Furtherfield. This event is also a precursor to a series of projects and initiatives which will be hosted at the WeShare Lab later this year.

“I have been bowled over by the enthusiasm and seriousness of the hacking community when faced with the question of how we can create and develop new tools to make music making accessible. This event is the first of many, and allows us to collaborate with the widest range of talent in creating the most innovative tools for a sector that desperately needs them. “ – Gawain Hewitt

For further information please contact Gawain Hewitt, Drake Music Associate Musician and Associate National Manager – Research and Development.

Drake Music breaks down disabling barriers to music through innovative approaches to making, learning and teaching music. Now in its 25th year, Drake Music continues to play a pioneering role in the development and imaginative use of Assistive Music Technology (AMT) to make music accessible. Drake Music is the only organisation in England specialising in the use of AMT to break down (physical/societal) barriers to participation.

Our focus is on nurturing creativity through exploring music and technology in imaginative ways. We put quality music making at the heart of everything we do, connecting disabled and non-disabled people locally, nationally and internationally. Drake Music is an Arts Council NPO.

The London Music Hackspace originated as a subgroup of the London Hackspace as a place to share thoughts, knowledge, technologies, processes and aesthetics on music and audio. We foster innovation by gathering skilled professionals and facilitating exchanges between disciplines, from software development to music installations and production. The Music Hackspace organises weekly events, including presentations and talks by artists and musicians, workshops, performances and unexpected collaborations. Music Hackspace are member of London Hackspace.

Drake Music and Furtherfield have come together to create WeShare, a new initiative building on the combined creative assets, specialisms and strengths of both our organisations. In a series of projects in the first phase of WeShare, supported by an organisational development grant from Arts Council England, we tested and piloted new ways of working and collaborating through projects such as Pecha Kucha Beta and Deconstructing Pecha Kucha. This year will see the launch of the WeShare Lab, which will support and host events similar to Hacking to Make Music Accessible.

WeShare has emerged from three years of successful partnership-working between Drake Music and Furtherfield who share a critical and creative engagement with art, music and technology with a focus on participation and collaboration. It aims to amplify the existing quality, reach and value of our organisations’ work, finding new ways to share knowledge, ideas, resources and opportunities; creating new ways of producing and sustaining socially engaged art and culture.

Furtherfield Gallery

McKenzie Pavilion, Finsbury Park

London N4 2NQ

T: +44 (0)20 8802 2827

E: info@furtherfield.org

Furtherfield Gallery is supported by Haringey Council and Arts Council England

Scratch is a programming environment that is easy to use and created with children in mind. Create and share your own interactive stories, games, music and art!

Codasign in partnership with Furtherfield will be running two Scratch weekend workshops for children and their parents at Furtherfield Gallery on Saturday 09 and Sunday 10 March: a morning session with 6-9 year olds (10-12pm) and an afternoon one with 9-12 year olds (1:30-4pm).

Please book your place.

All supporting material for the workshop will be available at learning.codasign.com.

What will you do and learn?

You will design and make a game or animation using the Scratch environment.

What do you need to already know?

You only need to have big ideas – no other experience required.

What do you need to bring?

You need to bring a laptop and an adult. The same adult can accompany multiple children. If you aren’t able to bring a laptop, just let us know by adding a note to your registration or e-mailing info@codasign.com.

What will be available during the workshop?

There will be drinks available, but you are welcome to bring along some snacks to feed your creativity.

Cancellation Policy

Full refund if registration is cancelled over a week before the course start, 50% if within a week of the course start, and no refund if within 24 hours of the course start.

VISITING INFO

Furtherfield Gallery

McKenzie Pavilion

Finsbury Park, London, N4 2NQ

Scratch is a programming environment that is easy to use and created with children in mind. Create and share your own interactive stories, games, music and art!

MaKey MaKey is a kit that lets you turn anything into a controller. Let your imagination go wild!

Codasign in partnership with Furtherfield will be running two Scratch + MaKey MaKey workshops for children and their parents at Furtherfield Gallery on Saturday 23 February: a morning session with 6-9 year olds (10-12pm) and an afternoon one with 9-12 year olds (1-4pm).

Please book your place.

All supporting material for the workshop will be available at learning.codasign.com.

What will you do and learn?

During this workshop, the children will practice using computational thinking and interactive design in creative projects through a variety of activities. The adults will even play a key role in these activities.

What do you need to already know?

You only need to have big ideas – no other experience required.

What do you need to bring?

You need to bring a laptop and an adult. The same adult can accompany multiple children. If you aren’t able to bring a laptop, just let us know by adding a note to your registration or e-mailing info@codasign.com.

What will be available during the workshop?

There will be drinks available, but you are welcome to bring along some snacks to feed your creativity.

Cancellation Policy

Full refund if registration is cancelled over a week before the course start, 50% if within a week of the course start, and no refund if within 24 hours of the course start.

VISITING INFO

Furtherfield Gallery

McKenzie Pavilion

Finsbury Park, London, N4 2NQ

Scratch is a programming environment that is easy to use and created with children in mind. Create and share your own interactive stories, games, music and art!

Codasign in partnership with Furtherfield will be running two Scratch workshops for children and their parents at Furtherfield Gallery on Saturday 09 February: a morning session with 6-9 year olds (10-12pm) and an afternoon one with 9-12 year olds (1-4pm).

Please book your place.

All supporting material for the workshop will be available at learning.codasign.com.

What will you do and learn?

You will design and make a game or animation using the Scratch environment.

What do you need to already know?

You only need to have big ideas – no other experience required.

What do you need to bring?

You need to bring a laptop and an adult. The same adult can accompany multiple children. If you aren’t able to bring a laptop, just let us know by adding a note to your registration or e-mailing info@codasign.com.

What will be available during the workshop?

There will be drinks available, but you are welcome to bring along some snacks to feed your creativity.

Cancellation Policy

Full refund if registration is cancelled over a week before the course start, 50% if within a week of the course start, and no refund if within 24 hours of the course start.

VISITING INFO

Furtherfield Gallery

McKenzie Pavilion

Finsbury Park, London, N4 2NQ

Blue Sausage Infant is the solo electronic project from Washington DC’s Chester Hawkins. Active on the live scene since the late 1980s, he’s shared the stage with touring and local luminaries, whose stylistic echoes radiate his own productions. Hints from prog, industrial, dark ambient, and noise all come across on BSI’s first LP release, Negative Space. Issued on Zeromoon in gorgeous packaging and colored 180-gram vinyl, Negative Space’s three tracks combine into a diverse snapshot of Hawkins’ musical creativity and expertise using a fair number of electronic and other diverse instruments (including electric toothbrush), all helpfully enumerated on the inner sleeve.

Side one is the single solo track “Motion Parallax,” a drifting space music riff that evolves through increasingly soupy accompaniments. From the Berlin overtones that emerge from the opening swirling white noise to a tribal electronic rhythm that reminded me of the proto-noise-punk band Chrome, BSI creates a diorama of timbral and harmonic landscapes. A distorted voice just out of comprehension earnestly and repeatedly strives, but fails to make herself meet and fuck understood, channeling an obscure Samuel Beckett character. Perhaps because of its murkiness, present even in the background of the rhythmic passages, Motion Parallax carries a lulling quality, a hard-edged long-form ambient work.

By contrast, side two opens considerably further towards krautrock with the title track, thanks to the assistance of a guitarist, a drummer, and a fourth performer on percussion and electronics. For all that side one referenced ambient, “Negative Space” draws from post-rock, with sustained guitar textures, rhythmic bass riffs, four-bar phrase structures, and a continuous dramatic build over the fourteen-minute performance. The side concludes with the shorter solo track “Subferal,” dense electronics dotted with sirens and alarms, led by an obsessive oscillation that starts on an intense single note and dissolves into swizzling distortion.

Originally posted on Furthernoise: http://www.furthernoise.org/index.php?url=page.php&ID=430&iss=96

Featured image: Gramophone Transmissions original artwork

Broken Harbour is an ambient project from Edmonton’s Blake Gibson, with two self-released albums to date available through various digital outlets. The more recent, Gramophone Transmissions, is composed largely from samples after a growing dissatisfaction with synthesizers. His source material included classical music from worn-out vinyl, CDs and cassettes, as well as some recordings of his own on voice, piano, and, mellotron. Overlaid with a vinyl patina, Gramophone Transmissions mines the surreal territories somewhere between Leyland Kirby and William Basinski, evoking musical memory through harmonies sustained and overlapped, and melodies whose contours have been worn smooth from forgetfulness and decay.

The first half of the album sets the stage with long, slow pulses, The opening track “Drift” features a short, delicate, and elegant piano run, which gave it a sparkle, a twinkle of light. But the piano becomes a glimmer, hovering in distant chords as the album progresses inevitably to a darker, more nocturnal climate, an increasingly featureless audio plain constructed from low strings and cavernous reverberation. A last lingering appearance comes as a channel bell in “Titan”, a repeated warning sounding through the fog, fraught with mythological overtones.

Modafinil (also known as Provigil) is medication used to increase wakefulness in those with sleep disorders, such as narcolepsy, sleep apnea, and shift work sleep disorder. To buy it, you’ll need to have a doctor’s prescription.

Buy Modafinil 200mg Online (buyprovigil) on BuzzFeed. Modafinil is a drug developed for the treatment of extreme lethargy. Despite being proven its effectiveness in the intervention of sleep …

The album’s second half, its three longest tracks, start with “Dark Clouds Approaching From The West,” full of murk and distant rumbles, seeking the tension in the faraway twilight storms without ever finding a release. “Maelstrom”‘s discordant voices will probably awaken anyone unwise enough to fall asleep to the previous lulling tracks. Its fleeting and wavering high strings introduce a slowly evolving series of shifting textures full of foreboding. The closer, “Unforeseen Consequences,” hangs on a single sonority forever before returning to the quietly evolving moods of the earlier tracks.

In early February 2011, while researching the Japanese post-war economic miracle for a Biosphere project, Geir Jenssen found an old photo of Mihama nuclear plant. The site of this futuristic-looking plant in so lovely a spot by the sea intrigued him. Were they safe from earthquakes and tsunamis? Further reading revealed many to be in quake-prone areas, some even by shores hit by tsunamis previously. Narrowing focus to Japanese plants, he determined to soundtrack them – architecture and design, location, potential risk. N-Plants was finished on February 13th. A month later a friend wrote: ‘Geir, some time ago you asked for a photo of a Japanese nuclear powerplant …how did you actually predict the future?…’

Several months on, Jenssen’s prophetic words take on an eerie resonance, though the mood of N-Plants is far from the dystopian desolation one might have projected. A more ambiguous affair, it reveals itself less of an isolationist gloomfest than a collection of retro-futurist downtempo ambient house that seems to hark back to Biosphere’s early 90s IDM orientation circa Microgravity. The music, deceptively pretty, has about it a robotic undertone, its clipped rhythms of (deliberately?) low timbral interest, tones with a slightly degraded edge, a patina of peripheral hiss and whirr, slender hollowed out drones, as if to represent an alienated view of the still life of these structures, and aspects of their architecture and morality through a quasi-Ballardian sci-fi expressionist haze.

With its hissing effluvia and ominous chord thematics, “Joyo” is closest to the portent the theme might have evoked, but overall there’s a lightness of touch, eye to the bright visions of 60s sci-fi rendered via a slightly askew downtempo IDM. Sonics tap into the retro-future, signalling a certain remote sensed nostalgia. “Sendai-1″ sets the tone, a machine koan with Orientalist marimba-like sequences and a vacated drone at the core; the subsequent “Shika-1” and “Ikata-1” evoke a similar air of serenity with a clinical faintly sinister edge, blithe glaze-eyed synthetics and syncopated beats pulsing functionally under warmly wheezing pads.

But for all Jenssen’s precision sound design, N-Plants strikes as a little underdone and strangely lacking in musical, if not conceptual, substance, from a man responsible for one of the Top Ambient albums of all time, Substrata. Where that album memorably sounded depths, N-Plants scrolls somewhat dead-eyed over flat planes, as on the evacuated chiming recursions of “Fujiko”. Much of the album sounds almost like a decades-old artefact with its intermediate technology synth sounds and blank drum pads. This depletion is doubtless deliberate, sound signifying the faded scientific glory of its subject – tarnished future visions, modernist hopes, revealed as vainglorious hubris. N-Plants is truly a Music for Powerplants, in the way Eno’s was a Music For Airports. But, as with this latter, ideational heft doesn’t suffice to make it the best musical work of a master sonician.

Those seeking more musical meat may appreciate more fully fleshed out realizations from The Sight Below:

The first interview with Jake Harries, took place on one of Furtherfield’s Radio broadcasts on Resonance FM, earlier this March 2011. Fascinated by the historical context that came out of the radio discussion, we asked Jake for a second interview, this time it took place via email.

Jake Harries has been making music in Sheffield since the 1980s and is a sound artist, musician/producer, composer and field recordist with a strong interest in media art and the practical use of Open Source audio-visual software. He was a member of electronic funk band Chakk which is best known for building Sheffield’s first large recording studio, FON Studios, in the mid 1980s. He is currently one of “freestyle techno” trio Heights of Abraham and The Apt Gets, a band which uses guitars and only Open Source software on recycled computers to create songs from spam emails. He is Digital Arts Programme Manager at open access media lab, Access Space, and the current curator of the LOSS Linux Open Source Sound a website dedicated to music made with FLOSS.

Marc Garrett: Lets talk a bit about your own history first. You were in a band in the 80s called Chakk, could you tell us a bit about that?

Jake Harries: Chakk was based in Sheffield during the mid 80s and we are best known for building a heavily used facility, FON Studio, Sheffield’s first large commercial recording studio. Chakk made “industrial funk” music, a mix of funk base lines and drums with influences ranging from punk to soul to free jazz and electronica. Our music was aimed squarely at the dance floor. We believed that technology, in this case the recording studio, was the most important instrument a band could have both creatively and financially.

MG: So, you are part of the electro music history of Sheffield with bands like Cabaret Voltaire & The Human League in the late 70s – 80s?

JH: Yes, but the band itself didn’t have too much commercial success, a couple of indie chart top 10s and a couple of low 50s in the main UK chart, so few people remember us now. People are more likely to remember FON Studio.

Recently a documentary has been made, called The Beat Is Law, about Sheffield music at that time, so perhaps there will be a bit more interest in the band.

MG: Open Source software is freely downloadable from the Internet for free and Linux is the most widely used Open Source operating system. How long have you been using Linux operating systems and Open Source?

JH: I had heard of Linux before, of course, but I came across music applications which were developed only for Linux in 2002-3 while searching for new software tools. These intrigued me sufficiently to install the operating system on a pc which I had fixed where I was working at the time.

MG: Do you feel that artists, techies and others are choosing Free and Open Source resources for reasons which connect with ethical and environmental issues and concerns?

JH: Well, I’d like to integrate into this answer the general themes of openness and transparency. FLOSS is akin to an encyclopedia of how to make things in the software realm because all the code is available for anyone to download and develop; closed, proprietary software is like a “sealed box” which it is illegal to prise open.

But it goes a bit deeper than that: in the world we are living in now the “sealed box” is increasingly becoming the mode of choice for all kinds of products, most of which, because they are designed to be superseded, have built in obsolescence. When something goes wrong with a product, you are unable to fix it yourself because you can’t get inside it, and even if you could you can’t find out how to fix it. If it is out of warranty, either you pay a lot of money to get it fixed or you throw it away; then you buy a new one! (Which is what the market wants you to do…)

So, it feels very much as if we are surrounded by technology we are not encouraged to understand and products with a limited life span: the obvious environmental concern is, “what happens to my ‘sealed box’ when I throw it away?”

Using a Linux operating system can increase the useful life of a computer by several years, and perhaps, if you can hack into them, other products too. So it is great if both hardware and software are open.

We also know that sharing knowledge is generally considered to be a good thing as it allows people to build on what has already been discovered. Being able to give the people in workshops the software they have been learning to use because it is FLOSS, rather than them having to pay several hundred pounds because it is only available on a commercial license, is great and often the idea of this kind of freedom takes a while for people to get used to if they’ve not come across it before.

MG: Why is it important as a creative practitioner to be using Open Source?

JH: Well, personally, I have realised that what I’m interested in is freedom, not just as a hypothetical, but the practical reality, finding out how to achieve some of it and if it is possible to sustain it. Free & Open Source operating systems and software are one way of stepping out side of the constant pressures of the commercial market places which dominate our culture.

We tried this in Chakk in the 80s with FON Studio, attempting not only to personally own the means of producing our music, the studio (allowing us to be outside the corporate system of production), but also to be able to explore our creativity in the way we wanted to. In the case of Chakk it didn’t work out. We had, rather cheekily, persuaded a giant corporate (MCA Records, owned by Universal) to bank roll it all and they found ways of scuppering our plan by making our product conform to their idea of the market place: transforming it into something “radio friendly” and bland, taking the energy and urgency out of the music. We were quite a politicised band and that energy was essential to our musical integrity.

However, when MCA dropped us we had a recording studio which could help nurture new music without too much external pressure, and this led to records produced there by local acts fulfilling their potential and going into the charts.

I think it is important for artists to have certain freedoms, to have ownership over the means with which they create their work. The fact that FLOSS allows you the user the potential of customising the tools you use and to distribute them freely via the web or other means is quite profound. And one of the real benefits of using FLOSS as a creative practitioner are the use of open standards and formats.

MG: OK, let’s move onto your own band: The Apt Gets. Now, since The Human League & Cabaret Voltaire, a whole generation has experienced the arrival of the Internet. Your group seems to reflect this aspect of contemporary, networked culture – a kind of Open Source rock band. Could you tell us about this band The Apt Gets, how you all got started and why?

JH: It began with workshops I was leading for musicians on FLOSS audio tools in 2007. The idea of an “open source rock band” came up – at the time we didn’t think there was one so a couple of the workshoppers and myself formed one. The Internet was the main source of inspiration really: we used recycled computers with Linux we’d downloaded, as well as guitars and vocals. I’m interested in re-purposing junk as raw material for creative processes and decided to re-use some of my spam emails as lyrics. We all hate spam, but re-contextualising it like this is fun, as is introducing a song by saying, “Here’s a classic Nigerian email asking for your bank details”. The themes of spam emails are generally things like greed & money, status & sex appeal as well as “meds”, so there’s more to them than you might think.

MG: Now, I personally know why, but others who are not as familiar with Linux and Open Source Operating systems, will not immediately know this. The naming of your band’s name – it’s specific to installing software. Could you tell us more about that?

JH: On a Debian Linux based operating system one can install software from the internet using an application called apt. One could type apt-get install the-name-of-the-software into the command line and apt will get the software from what is called a repository on the Internet, where the software is stored for download. We thought that if you called someone an Apt Get it could be interpreted as an insult meaning something like, clever bastard. So, that’s why we named the band The Apt Gets.

MG: How long has your research project with FLOSS been going?

JH: The research project started in 2007. Ever since I began to use FLOSS I’ve been interested in the practical realities of using it, particularly as an every day set of tools, as an ordinary computer user would use it: for instance, when I do work on the arts programme at Access Space I don’t use anything else. So, it made sense to discover how a number of non-Linux using musicians would find using FLOSS audio tools – if I was being an advocate for FLOSS I ought to look at it from the new user’s angle and discover how far they could go and what kind of time scale they need.

MG: And the web site address is?

JH: http://audiotools.lowtech.org

MG: How easy is it for someone with little or no experience of Open Source software and Linux based operating systems to install it?

JH: It is quite easy nowadays. A Linux distribution like Ubuntu has an easy to follow installer which allows you to create a dual boot if you want it, that is, keeping your Windows system as well so you have the choice of both.

MG: At Access Space in Sheffield, you are curator and researcher of LOSS (Linux Open Source Sound) a website dedicated to music made with FLOSS – which is basically LOSS with the letter ‘F’ added, meaning ‘Free Linux Open Source Sound’ – FLOSS!

JH: Yeah! Free is the word! It is a repository for music made with FLOSS tools and released under a Creative Commons license. You can freely download and upload tracks. Initially it was based around two projects, a physical CD issued in 2006 curated by Ed Carter, and LOSS Livecode, a mini conference and gig curated by Alex McLean and Jim Prevett based around the international livecoding community. The website is at http://loss.access-space.org.

MG: What is Access Space and what is different about them as a group?

JH: Access Space is an open access media lab, based in central Sheffield. It uses reused and donated computer technology to provide Internet access and Open Source creative tools, free of charge, five days a week. It started in 2000 and has become the longest running free Internet project in the UK.

We recycle computers, put on art exhibitions, creative workshops and sonic art events. We’re currently developing a DIY Lab, modelled on MIT’s FabLab or fabrication laboratory. This will be an interface between the physical and digital domains where new kinds of creative activity can be developed.

MG: What operating systems would you suggest to newbies coming to Linux for the first time?

JH: Ubuntu or its derivative, Linux Mint, are both very user friendly for everyday use. For audio try Ubuntu Studio, 64 Studio or Pure:dyne.

MG: And regarding yourself, what are you using?

JH: I have set up eight Ubuntu Studio pcs for use in audio and video workshops at Access Space; and I use Pure:dyne live DVDs if I’m out and demonstrating on other people’s pcs. For everyday use, again Ubuntu Studio with a few additional applications like OpenOffice.

MG: Thank you for a fascinating conversation.

JH: It was a pleasure…

Open Access All Areas: an Interview with James Wallbank about Access Space by Charlotte Frost

http://www.metamute.org/en/Open-Access-All-Areas

Ubuntu Studio 11.04 release.

http://ubuntustudio.org/

64 Studio Ltd. produces bespoke GNU/Linux distributions which are compatible with official Debian and Ubuntu releases. http://www.64studio.com/

Puredyne is the USB-bootable GNU/Linux operating system for creative multimedia.

http://puredyne.org/

Pure:dyne Discussion, interview by Marc Garrett & Netbehaviour list Community 2008.

http://www.furtherfield.org/interviews/puredyne-discussion-netbehaviour

Featured image: Radion at NetAudio London festival 2011.

NetAudio London Festival, 13th – 15th May 2011.

A three day festival that explores music environments in the digital age of networked technologies. http://www.netaudiolondon.org/

Marc Garrett interviews Andi Studer of NetAudio London, about their latest Festival at the Roundhouse and other venues in London, from Friday 13th – 15th May 2011. Showcasing work of artists who use digital and network technologies to explore new boundaries in music and sonic art, their festivals encourage participation in all forms: interactive sound art installations, conferences, workshops, collaborative online broadcasting and headline shows. This year promises to be a special event, headlined by the legendary Nurse With Wound and many more – read on.

Marc Garrett: This seems like an amazing festival. Not just because it’s context relates to my own background and Furtherfield’s own connected communities and its history in exploring an engagement of contemporary, networked creativity which was once perhaps, considered to be at the edge of art. But now, it does seem as if a new passion is alive and kicking, representing what exists across the genres of art, technology and social change.

The Netaudio London festival began its life in 2006, why did you chose to set up such a dynamic and involving festival, and who are your influences?

Andi Studer: The first Netaudio London grew out of a general passion for electronic music, combined with the recognition of a booming netlabel scene distributing new music with CC licenses for free download. Culturally it spanned the three fields of club culture, avant-garde music and net-politics. During the research phase, we came across of string of European festival projects with the same scope and decided to align with them, so after Netaudio Berne and Cologne, in 2005, London took it’s turn in 2006. Over 3 days we presented more than forty acts in club as well as gig settings; we hosted cultural discussions, organised a knowledge fair around digital music distribution and premiered an the audio installation by Si_COMM, S.E.T.I and N-Spaces… good old days!

MG: What do you feel is important about the Netaudio festival and how does the current one relate to contemporary culture?

AS: Netaudio aims to play an active role in the ongoing process of exploring how technologies, and particularly the Internet, shape our lives. Within this vast field, we focus our work on sonic culture, music and sound art, but reach out to wider aspects such as politics and protest or collaborative creativity.

Whereas in 2005/06 much of the cultural discussion was driven by an incredible optimism about new communication and distribution channels, this year’s festival may pick up on something best described as ‘cyber realism’. The festival, and particularly the conference, building on our 2010 research project, presents a strong case for individuals taking action. And in process of so doing, we are interested to explore what emerging digital tools they use to create new sound art/music, as well as in the social and political endeavours related to their creative work.

MG: Why chose to include those who have a history in net art, critically engaged thinkers invlolved in networked culture, and many who have been and are part of the (new) media art generation?

AS: We recognise a continuation of creative and socially aware work, enabled by network technologies. Including emerging as well as established projects, some dating from well before the WWW time, allows us to show this continuation and hopefully furthers the wider understanding of these different elements/groups. Whilst there are clear differences between them, there are also many overlaps and we hope that the inclusion of as many as possible in the debate and the wider festival allows for an exploration and greater understanding of these overlaps, and differences.

MG: Your festival includes a visiting member from UK Uncut who will be discussing with others at the Conference and Workshops, regarding the proposed theme of ‘politics and protest; creativity and collaboration; digital futures and analogue survivals.’ They have made headline news regarding their activities challenging the government’s ongoing cuts, and have been actively involved across the country targeting corporate tax dodgers and the banks who caused the financial crisis.

Do you think that UK Uncut’s own perceptions and its activism reflect the festival audience’s general interests and feelings on the matter, across the board?

AS: The participation of UK Uncut is confirmed, but the speaker is to be announced. Whilst some festival audience members may be sympathetic with UK Uncut’s perceptions and activism, others may not. Similarly, whilst members of the festival programming board may have sympathies with UK Uncut’s cause, the festival as such does not necessarily share the same cause with UK Uncut. The reason for inviting UK Uncut was their very successful work as a technology savvy protest movement, as well as their exploration of new forms of protest, particularly sit-ins involving poetry readings and the singing of songs. We are interested to find out more about how they use technology and music/sound in their cause. Presented in a panel with Jeremy Gilbert, Mark Fisher and Anthony Iles, we hope to show how their work sits within the incredible role music had and continues to have in social, political and economic protest.

MG: Nurse With Wound is headlining the festival and they are legendary in the underground music scene. Spanning a career of 30 years plus, under the curatorial guide of Stapleton who has seen NWW collaborate with a highly respected troop of free thinkers including David Tibet (Current 93), William Bennett (Whitehouse) and Andrew McKenzie (Hafler Trio). Many artists who have been working with technology and similar experimental genres, are influenced by those of industrial and avant garde music scene, such as Throbbing Gristle, Cabaret Voltaire, Virgin Prunes, This Heat and NWW, so it seems fitting to have them in the festival, with their peers and of course, an equally interesting selection of younger sound artists and musical explorers.

It may say seem like the perfect decision now, but how did you come to the idea of asking Nurse With Wound and what are the links with the other aspects of the festival?

AS: To have Nurse With Wound headlining our festival is a dream come true. Their achievements in anarchic, experimental, DIY, post-industrial music is unparalleled, and it is possible to find many of their approaches in the current new music produced by emerging musicians. This is something we hope to draw on in the rest of the festival.

At KOKO we will also present a newly commissioned live collaboration between Bruce Gilbert (ex-Wire) and Mika Vainio (ex-Pan Sonic). This opportunity to present new work came about though the direct continuation of an ongoing enquiry into collaborative creativity, as featured on one of the three conference panels. This is definitely also a strong theme in the work of Radian, the opening act at KOKO.

I’d urge anyone who is coming to see NWW at KOKO, to join us at the Roundhouse for the afternoon programme, particularly the conference, but also with the Open Platform stage, we hope to showcase some glimpses of the NWW legacy.

It may be worth mentioning the broadcast strand of the festival here too. Enabled by the Roundhouse Studio facilities and with creative input from Ed Baxter of Resonance104.4fm we are able to feed the festival back to the online domain for the first time. Throughout the afternoon of the 15th May, we will present a live web-zine, thereby leading an enquiry into the future of broadcasting. As part of this we will present three new pieces of work by the commissioned artists: Stefan Blomeier, VHS HEAD, and Liliane Lijn, the latter presenting an online adaptation of her Power Game project.

MG: This interesting development warrants investigation, not only because there is an an influx of new interest from a much larger informed and adventurous audience across the board but also because it represents an obvious, cultural dynamic at work. Reflecting a ‘real’ contemporary interest for something different to happen, beyond the remit of normative, art world restraints and its usual, hermetically sealed approaches. We will definitely be there ourselves. To experience what promises to be an engaging and critical conference, but also to explore and enjoy the other varied live events and projects.

The Conference – will bring together theorists, practitioners, activists and academics to address a challenging set of themes in 21st-century culture, featuring speakers including Matthew Herbert and Cecelia Wee: politics and protest; creativity and collaboration; digital futures and analogue survivals.

http://www.netaudiolondon.org/2011/strand/conference

Sound Art – In partnership with Call& Response Netaudio presents an event of 8-channel immersive audio-works. The dynamic and varied explorations of the nine prolific artists brought together by Call& Response highlights the vibrant and diverse field of contemporary sound art. Also there’s the Sonic Maze, an immersive series of sound art installations set in the Roundhouse Studios. http://www.netaudiolondon.org/2011/strand/sound-art

Broadcast – Using the format of a live webzine, Netaudio Broadcast will explore the future of broadcasting with a series of video and radio features. Netaudio Broadcast is co-curated with Ed Baxter of Resonance104.4fm. http://www.netaudiolondon.org/2011/strand/broadcast

Live Music – Starting at cafe OTO on 13th with Robert Piotrowicz (http://www.myspace.com/robertpiotrowicz) and Valerio Tricoli, continuing at Apiary with the runsounds hosted late night event; and the main live show of the festival, a rare live appearance from Steve Stapleton’s Nurse With Wound (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nurse_with_Wound), a special commission performance by Bruce Gilbert (ex-Wire) and Mika Vainio (ex-Pan Sonic) and Radian.

The 2011 Netaudio London festival supported by the National Lottery through Arts Council England and by the Austrian Cultural Forum London. It is presented in partnership with The Wire, ResonanceFM and Last.fm and supported by the Roundhouse and many more.

Musical workshops inspiring a sense of wonder in the endless combinations of sounds and rhythms in poetry, song and nature.

Participants: 90 students between the ages of 10 and 14 from Horsenden Primary School.

Artist: Michael Szpakowski (video artist, composer and facilitator)

90 students between the ages of 10 and 14 from Horsenden Primary School engaged in an exploration of the seasons through spoken/sung words and rhymes, and collaborated to create a collection of musical pieces using a variety of musical instruments. This project supported children’s reading ability by exploring rhythm through music, as well as the creation of a permanent sound artwork for the school garden that changed with the seasons to inspire a sense of wonder in the endless combinations of sounds and rhythms in poetry, song and nature.

The artist Michael Szpakowski worked with 14 small groups of pupils doing music and sound drawing on quotes from nursery rhymes and using a range of stimulating and unusual ways of making sounds. The work was digitally recorded in order to create a “generative” piece of music and sound-scape. Generative means that the computer is programmed to play back the fragments of the sound in a semi-random order so that they would constantly unfold and combine in different ways, like a kind of musical kaleidoscope.

Partners:Creative Partnerships, Horsenden Primary School.