Between July 27th and August 29th, 2010, the eleventh edition of the FILE festival is taking place in Sao Paulo (Brazil), at several locations along the popular Paulista Avenue. After a decade of existence, this veteran festival, which spreads over several cities in Brazil (including Rio de Janeiro and Porto Alegre) as well as other international locations, has introduced for the first time its own award: the FILE PRIX LUX. With a total amount of approximately 120,000 euros, distributed in three categories, the prize is unprecedented in the continent and has received, on this first edition, 1,235 registrations from 44 countries.

Yet this award is not the only remarkable aspect of this year’s festival, which stands out for being particularly accessible to the general public. On the one hand, the exhibitions, performances and workshops as well as the symposium have no entrance fees, and therefore there have been many visitors, most of all young people who line up every day to experience the interactive installations at the FIESP-Ruth Cardoso Cultural Centre. On the other hand, the festival organizers, Ricardo Barreto and Paula Perissinotto, have developed this year a project that takes digital art to the Paulista Avenue by placing several interactive artworks at different locations in the public space. Finally, even the FILE PRIX LUX has been open to the interaction with the public by introducing a popular vote category and an online voting system which was accessible between May and June. This openness sets a good example of how media art festivals can engage the general public to approach this somewhat ignored form of art.

In general terms, the award categories at media art festivals have been subject to change as the creative uses of technology evolved during the last decades. The FILE PRIX LUX has the advantage of being created at a time in which it can be relatively safe to set up a few broad categories that cover most of the forms of combining art and technology. Only three categories have been established: Interactive Art (which usually refers to objects and installations that respond to inputs from the viewer/s), Digital Language (related to the festival’s title and which embraces any artwork that deals with language, narrative, code or text in a generative or interactive manner) and Electronic Sonority (the category assigned to any artwork in which the production or manipulation of sound is a key element). These three categories prove to be comprehensive, as shown by the diversity of the projects distinguished with a prize or an honorary mention: immersive interactive installations, musical performances, urban interventions, bioart pieces, a collectively created machinima movie and even an iPhone app are among this year’s FILE PRIX LUX awardees.

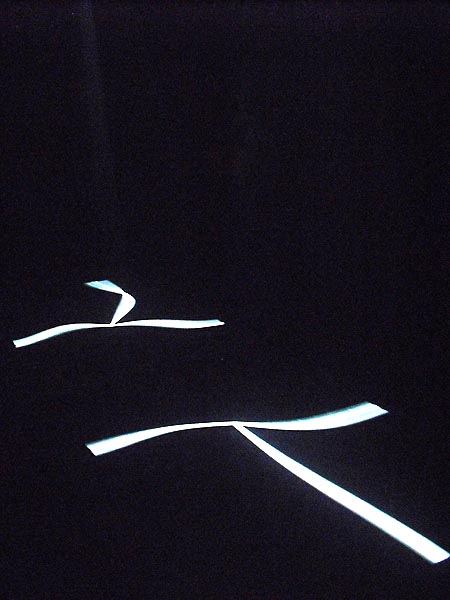

In the Interactive Art category, the winners are Ernesto Klar for Relational Lights (1st prize) and Kurt Henschläger for Zee (2nd prize). Both present immersive environments in which light and space are key elements, although the interaction is totally different. Klar’s work invites the viewer to interact with two projected geometric drawings inspired by the work of Lygia Clark. In a hazy dark room, the viewer sees two T-shaped projections of white light on the ground, which form a three-dimensional space which reacts to the visitor’s presence. The interaction is playful and really beautiful in its simplicity, whilst also limited in time: after a few minutes, the projections suddenly stop reacting to the user’s movements and reconfigure themselves in a new shape. This abrupt interruption is consciously introduced by the artist in order to remind the viewer that the artwork has a life of its own. In contrast, Henschläger’s Zee takes place mostly in the mind of an audience exposed to an overdose of audiovisual stimuli in a foggy room. Continuing the experience of his acclaimed performance FEED, this time the artist allows the viewer to walk around the space and have a more meditative sensory experience.

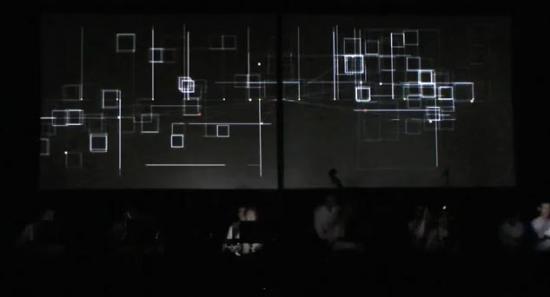

The Electronic Sonority category has brought together several outstanding works, among which Jaime E. Oliver’s Silent Percussion Project and TERMINALBEACH’s Heartchamber Orchestra have been distinguished with the 1st and 2nd prize, respectively. In both projects the human body is incorporated in a novel form in the creation of music, the sound being produced, moreover, not simply by direct inputs but by complex interactions in a constant flow of data. Oliver’s instruments convert the shapes created by the performer’s hands into streams of data that generate, in turn, different sounds. These sounds are not always the same, as could be the case in a traditional instrument, but are changed by the variables established in previous interactions. Thus, Oliver does not simply create a new form of interacting with an instrument but rather a new form of creating music. In a similar way, the [i]Heartchamber Orchestra[/i] project developed by TERMINALBEACH (Erich Berger and Peter Votava) explores a form of creating music based on a feedback loop in which the performers are writing and following the score at the same time. As the artists state, in their project “the music literally comes from the heart”: a network of 12 independent sensors record the heartbeats of the musicians in an orchestra and sends the data to a software that generates a musical score in real time. The musicians play the score as it is displayed on the laptops in front of them, while their heartbeats set the notes in a continuous cycle in which music and performer constantly influence each other.

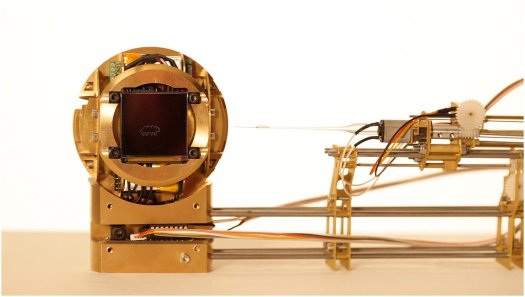

Digital Language is certainly the broadest category of this FILE PRIX LUX, its awardees being quite dissimilar in the formats they use and the objectives of their respective projects. The organizers define this category as including “all research and experiments in the ambit of the multiple disciplines that use digital media”, and the winners exemplify how diverse these disciplines can be. The 1st prize winner, Tardigotchi by the artists collective SWAMP (Douglas Easterly, Matt Kenyon and Tiago Rorke) is a bioart project that sets a critical comparison between artificial and real life. A nicely designed, steam punk-inspired device hosts, on the one hand, a tardigrade, a microorganism measuring half a millimeter in length, along with a robot arm that injects a substance that feeds the creature and a heating lamp that provides warmth. On the other hand, a digital display shows the virtual avatar of this tardigrade, with which the user can interact. Humorously referencing the popular Tamagotchi toy, the artists create a link between the avatar and the real creature: when the user presses the button to feed the avatar, the device inserts real food in the environment of the tardigrade; when an email is sent to the digital creature, a heating lamp gives warmth to the microorganism. Thus, interacting with the virtual pet has consequences in a real living being. This brings our attention into what we can consider alive and how we emotionally attach to artificial creatures while at the same time we undervalue the existence of other living beings. On a different approach, the 2nd prize winner, Hi! A Real Human Interface, by the collective Multitouch Barcelona (Dani Armengol, Roger Pujol, Xavier Vilar and Pol Pla), proposes a more human relationship with technology. A video presents the concept developed by this interaction design group of a different GUI in which a real person is displayed as impersonating the computer. Common interface elements are replaced by handmade physical objects which remind the aesthetics of a video by Michel Gondry. The result is a playful form of interaction in which simple operations such as checking email or upgrading the operating system are shown as actions carried on with real objects by a person inside a box. The proposal is engaging and certainly sets a departure from the old desktop concept, yet it remains unsure to what extend this type of interaction can be applied in a real operating system.

The works that obtained a Vesper statuette (symbol of the FILE PRIX LUX award) along with the also outstanding Honorary Mentions are exhibited at the FIESP-Ruth Cardoso Cultural Centre in a group show that also includes FILE Media Art, a selection of more than 70 works that can be accessed on several computers, as well as a selection of videogames and machinima films. The exhibition is thus richer in content than it would seem at first sight, as the space is divided in numerous sections that conceal several installations which demand (as usual) almost total obscurity. The artworks are well presented, although at times the sound from one installation invades the others, and there are no wall labels that inform the viewer about the concept of the piece or the way to interact with it. The latter, much-discussed issue is quite important, since the info-trainers cannot explain the artworks to every visitor, and quite often this entails that some people may not interact with the pieces or worse, start smashing buttons or interfering projections blindly in the hope of modifying them. Despite this fact, the exhibition has proven to be very successful during the first week of the festival, with a steady flow of visitors who showed a profound interest in the artworks.

A part of the exhibition is devoted to the FILE MACHINIMA section, curated by Fernanda Alburquerque, who selected over 40 works. Among these is the award winner in the Popular Vote category, War of Internet Addiction, by Corndog and the Oil Tiger Machinima Team from China, a 64-minute movie collectively created by players in the MMORPG War of Warcraft. More than mere entertainment, this film has been created as a form of protest against the Chinese authorities’ attempt to control the access and commercial benefits derived from the WoW game, which is extremely popular in the country. The film has had 10 million views since January 2010 and despite being available only in Chinese, it has been the favorite work of those who participated in the online voting system of the FILE PRIX LUX. Besides this feature film, other short films explore the possibilities of building narratives in virtual environments such as Second Life and videogames such as Half Life 2, Eve Online or Shadow of the Colossus.

In addition to the main exhibition, the FIESP Cultural Centre hosts a series of performances and screenings. Under the title Hypersonica, the festival presented a series of digital music performances, among which where the two winners of the FILE PRIX LUX in the Electronic Sonority category. FILE DOCUMENTA, curated by Eric Marke, offers in its 5th edition a selection of “rare and new” documentary films, among which Andreas Johnsen’s Good Copy Bad Copy, an interesting exploration of the conflicts between remix artists and copyright owners, or Robert Baca’s Welcome to Macintosh, which records the first years of the history of Apple Computers.

The symposium, hosted by the Instituto Cervantes in Sao Paulo, gathered several experts and artists who presented their explorations in the theory and practice of media art. Among the most interesting contributions were the presentation of Prof. Espen Aarseth on the aesthetics of ludo-narrative software, and the colloquy of South American digital art, in which Raquel Renno (Brazil), Jorge Hernandez, Ricardo Vega (Chile) and Vicky Messi (Argentina) discussed the current developments in the media art scene in the South Cone.

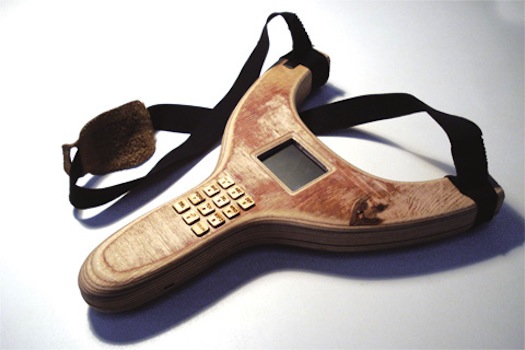

Alongside the FILE PRIX LUX, the most outstanding feature of the present edition of the festival is FILE PAI (Paulista Avenida Interactiva), which takes several interactive artworks to the public spaces in the Paulista Avenue. Interactive art offers the possibility of bringing art to the public space in a more efficient and dynamic form than what is usually known as “public art”. As Ricardo Barreto states: “the public environment is not something empty, aseptic and dead, as is the old white cube; on the contrary, it is an environment teeming with life, with multiple interests and multiple behaviors”. Interactive art integrates itself into this environment and is much more apt to relate to a public that is now willing to take an active role. The organizers of the FILE festival have distributed twelve interactive artworks along the Paulista Avenue, at subway stations, inside shopping malls, and even in a bus. The selected artworks include, among others, videogames such as Patrick Smith’s Windosill or the celebrated games of That Game Company, Flower and Flow; VR/Urban’s SMSlingshot, an urban intervention project that allows users to write a message in a custom-made slingshot that incorporates a screen and a keyboard and then send the message to a wall, where it is displayed as a virtual graffiti; Karolina Sobecka’s Sniff, an interactive projection in which a virtual dog reacts to the presence of passersby; the installations of Rejane Cantoni and Leonardo Crescenti Piso and Infinito ao Cubo, which attracted a large number of people, and the sound piece Omnibusonia Paulista by Vanderlei Lucentini, which is played in a bus as it moves along the avenue, interacting with several points in the itinerary and thus generating a new set of sounds in every trip. These works reveal the possibilities of integrating interactive art in the public space, to the point that, as Ricardo Barreto indicates, “the new paradigm of public art will be the interactive city”. The busy Paulista Avenue is certainly a good location for the creation of an emerging, interactive city.

In this 11th edition, the FILE festival has achieved a state of maturity. The FILE PRIX LUX, FILE PAI and an estimated 25,000 visitors to date support its claim of being the largest festival of its kind in Latin America, and a steady event that places Brazil in the map of the international digital art scene. In a tightly interconnected world, each region is a node: there isn’t a center and a periphery anymore, there are no colonies. FILE exemplifies how a region can become a powerful node in this network by promoting the most recent developments in art and technology, avoiding obsolete distinctions between North and South and becoming a point of development for the future stages of our digital culture.

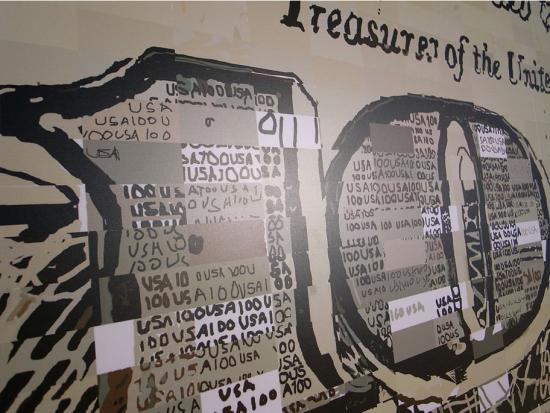

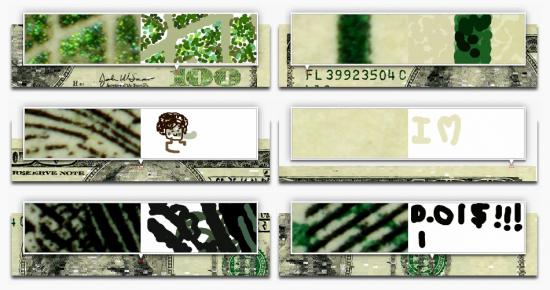

Arriving at the homepage of Ten Thousand Cents, an Internet artwork by Aaron Koblin and Takashi Kawashima, a mottled image of a one hundred dollar bill slowly fades into view. Ben Franklin looks out sedately. Mousing over the large image, the cursor is replaced with a small red rectangle. And here lays the beauty of the project; with the click of each rectangle, a zoomed in portion of the one hundred dollar bill is revealed. On the left side is a high-resolution photograph of that tiny portion of the bill. On the right side, a real-time moving image plays, revealing how the image was drawn by a human hand in a drawing program created by Koblin and Kawashima. There are, in fact, 10,000 such rectangles and each was created by a Turker through Amazon’s Mechanical Turk marketplace.

Over the course of five months (from November 2007 to March 2008) Koblin and Kawashima posted tasks, known as HITs, Human Intelligence Tasks, on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk site. Having broken down an image of a one hundred dollar bill into 10,000 sections, Turkers were tasked with redrawing their assigned section. Each Turker was paid $.01 for the task, making the total payment of drawing a one hundred dollar bill one hundred dollars. (Prints of the project can also be bought for one hundred dollars. All proceeds are donated to the One Laptop per Child (OLPC) project) Each Turker worked anonymously, unaware that what they were drawing was a section of a bill or that their work would eventually be combined with other Turkers’ work to create an art project. The variability is endless. Some Turkers methodically draw in the lines and painstakingly shade in boxes. Some quickly slash the paint tool across the page; one imagines they felt they had better things to do with their time. Some are cheeky, using the space for digital graffiti or messages like “I love U.” Most copy the image exactly. Yet, with the differing movements and tempos, every one suggests a different story and different person behind the tool. I suggest you take a few minutes and watch the unfolding scenes. They are oddly, satisfyingly banal and beautiful.

The project and its presentation on the website are undoubtedly elegant. Yet, the conceptual work behind the piece is a bit murkier. The project description states, “The project explores the circumstances we live in, a new and uncharted combination of digital labor markets, ‘crowdsourcing,’ ‘virtual economies,’ and digital reproduction.” Big and important themes. What are the implications of crowd-sourcing for creative work? For any kind of paid work? Where is the distinction between work and play? Creativity and re-presentation? In this deeply networked age, what are the evolving relations between individual and collective action?

The Mechanical Turk, made by Wolfgang de Kempelen in 1769, caused a sensation in 18th and 19th century Europe, first for its existence as a seemingly intelligent chess playing automaton – one who could beat Ben Franklin and even Napoleon in chess – and subsequently, for being an infamous hoax. Inside of the automaton was in fact a man, a skilled chess player. The Mechanical Turk was no thinking machine. It was an elaborate performance of concealment and human skill.

In 2005, in an ironic (and some might say distasteful) turn of events, Jeff Bezos of Amazon named a new business venture, Amazon Mechanical Turk. The idea was to make a digital marketplace that capitalized on the unique intelligence of human agents. Broken down into microtasks, known as HITs, Mechanical Turk provides a means to accomplish those tasks that humans can do quickly but which would take computers much longer to do, for instance, tagging images, taking surveys or transcribing audio recordings. This Mechanical Turk is also a performance of human skill, one that revels in its basis in human intelligence – Bezos calls it “artificial artificial intelligence” – but one that also operates within a mode of concealment and indeed, alienation.

As Katharine Mieszkowski of Salon wrote about Mechanical Turk in 2006, “There is something a little disturbing about a billionaire like Bezos dreaming up new ways to get ordinary folk to do work for him for pennies.” Critics of Mechanical Turk abound, and their objections point to the insidious labor relations that Mechanical Turk enforces, implying that Mechanical Turk approaches a virtual sweatshop. The system was designed for employers, not employees. The earnings of Turkers fall within a gray area of digital labor, officially being classified as contractor work, subject to high self-employment taxes and no option for benefits. Although a rating system protects employers, in so far as employers can choose to reject a work offer from a Turker or refuse to pay a Turker if the work is completed unsatisfactorily, no such system protects Turkers. As advocates of a Turker Bill of Rights have pointed out, there is no effective outlet within Mechanical Turk for Turkers to voice grievances against employers. What does exist is a vibrant community forum, Turker Nation, where Turkers advise each other on known scammers.

Moreover, although anecdotally Mechanical Turk is understood as more game or past-time than employment, a recent study out of University of California, Irvine’s Informatics Department points out that almost a third of Turkers rely on Mechanical Turk as a source of income. Another study found that nearly half of Turkers report their motivation for working as income related. For this population of Turkers, it is troubling to consider the possibilities of exploitation and unfair labor practices.

In this light, I find the artists’ neat appropriation of the mechanisms of Mechanical Turk unsettling. The implications and the stakes of Mechanical Turk as an economic system are left untouched. And considering that the artists chose to create a representation of money and employ Turkers, these dimensions of economy and labor are present but disappointingly unaddressed.

Yet, the moments in the project that remain in my mind’s eye like lovely specters as I glance at the dollar bill that I traded for coffee this morning, are the movements of the individuals who drew each section. On this level, the project is like a fantastic cabinet in which each drawer opens onto a new wonder. Perhaps what Ten Thousand Cents effectively offers is not a statement about labor politics or late capitalism’s continuing ability to provide structures for domination and exploitation. Perhaps Ten Thousand Cents asks us to take a different step toward understanding “the circumstances we live in,” revealing the endless variability of individual expression. In this networked age, we often act collectively, that is, together, parallel, most often without knowledge of the larger directions toward which our actions will lead. Collaboration, laboring together, is notion whose meaning is expanding and changing in the 21st century. What remains, even among protocols and code, is individuality. Though we are subsumed by larger structures, we do have spaces for self-expression and self-formulation. Leave an exploration of the limits of these spaces to others – and I surely believe we must consider the limitations. Yet we must also explore and value the spaces of possibility and the domains where we are active agents. We are called to remember that every artifact is irreducible to its mere instance in the world – it is a sum of processes and individual actions.

Of course, “the circumstances we live in” also requires us to keep in mind the bottom line. It’s all about the Benjamins, as the phrase goes. In response to a HIT, no less, requesting an answer to the question, “Why do you complete tasks in Mechanical Turk” one Turker wrote, “I do it for the money!”