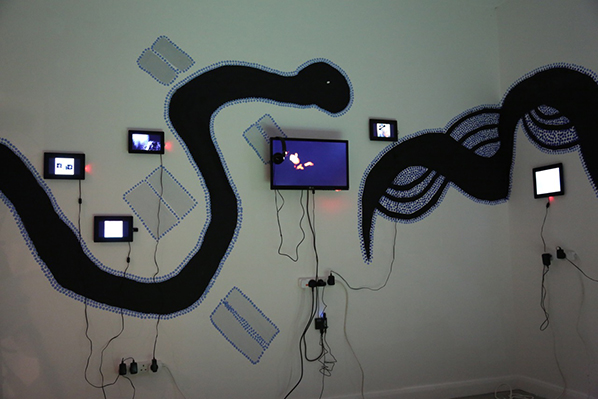

In this special feature Steve Jampijimpa Patrick writes about YAMA, the name given to the installation currently on display as part of the exhibition Networking the Unseen at Furtherfield Gallery.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

I want to tell you about YAMA. This is the Warlpiri word for a shadow, or reflection. It’s also a word that we use to describe a meeting or a meeting-place; we gather under a tree that casts a shadow (a reflection of its shape) onto the ground, and we talk in a group – both men and women together, equally – to make decisions and to reflect on ourselves and our lives. But it’s deeper, too. In yapa (Aboriginal) culture, if someone says “you don’t have a shadow”, it means you don’t exist. All the birds, all the small animals, trees – these things all have a shadow; all of your country and everything in it; this is your universe. How can you reflect your universe? And what about you, reader? Does your homeland reflect you?

I’ve been all over the world, searching for ngurra kurlu (the home within). Each country’s, each people’s ngurra kurlu is different. If you don’t speak your language, if you don’t know your culture, the songlines of the animals in your country, how can you express yourself or where you’re from? This reflection happens through language, through dance, art, even food – that’s ngurra kurlu. There is a universe and we are its shadow.

We yapa say “don’t become Australian, become Australia”.

That’s ngurra kurlu.

I am writing this from Germany, we (Neil Jupurrurla Cooke and I) were in England for a week working on YAMA, a multimedia installation with Napanangka (Gretta Louw) for the Networking the Unseen exhibition at Furtherfield. Every day we walked through Finsbury Park and the people we saw were really alive there, playing, walking, school children running through, watching the birds and the squirrels. But when we go into town, we feel closed up again. We went to the Horse Guard. Where I come from, the horses roam free – they are really alive. We don’t know their skin name , we don’t have a song for them because they’re feral animals, brought into our country by kardiyah (white people) – but they’re free. When we see the horses there in London trained to stand still like that, like they’re stone, we feel sad for them.

Then we look around and see those buildings round there (in Westminster). We’ve seen those buildings before. Even though we’d never been to London. They’re like underwater, you know, that coral when it dies – when it’s bleached – that’s what those buildings are like. Every thing, both living and created by the living, is a reflection of our universe. Imagine you are a little ant and you are walking through tombstones – this is how it feels for us to be in that place. I guess the people that made those towers are trying to express power, they want to have power over other people. They build those bleached towers and statues tall on columns to make the other people feel small. That’s a crazy world, when I’m coming at it from my culture.

Your home is going to reflect you and you’re going to reflect your home. So, think about your home and what it says about you.

For us, the things we look up at are the stars. We’ve always known them and learned from them. They are part of our ngurra kurlu. What about that North star that you have here in the northern hemisphere – they say it doesn’t move. Maybe that’s why you have one leader, one queen, who doesn’t change. Down in Australia, we have five emus (the southern cross) – we live by that law. We call ourselves an emu country. You bear countries reflect your stars, too. I like to think that the queen is the ultimate kurlungu (guardian) for the country, but a kurlungu needs to really look after all their people and their country. Is that what’s happening in your country?

I wonder what would happen if you brought an emu up here and just let it walk around. I’ve never seen it but I think it might start heading south. We have a word for ocean, mangku-rla, even though we’re a desert mob. This shows how ancient our songlines are – they existed before us; they created us. We were supposed to be noble savages, from the settlers’ point of view we weren’t supposed to know about the ocean or what was on the other side, but our Emu Dreaming tells the story of the emu swimming across the ocean. He was a nervous emu because he was being chased into the water by dogs. I think that was when the emu went between the continents to make relations with the ostrich and the rhea bird and the moa. There were big, flightless birds like the emu on each of the continents. In the Jardiwanpa story, the emu comes out of the water and shakes himself like a dog. This is reflected in the stars as well; our emu stars (the English name is the Milky Way) come up after the wet season.

In yapa culture, we know that we didn’t create the body: our universe, our country created us. That’s why I am a black man from Australia – my country made me like this. This is what you call evolution. You can have bears in the north, and we have emus in the south. Our countries created those beings. Yapa have always known that this is how things are created.

You live in the bear countries; even without people knowing it, they are reflecting what the bear is trying to teach them. We live by the emu. I can’t tell you what the bear is teaching you, I’d need to live here a lot longer, but you can learn to hunt the knowledge that the bear is trying to show you.

There are food sources for your stomach and there are some for your mind. Both are equally important. If you are hunting for goanna you bring it home and share it with your family and your community. If you are sitting, talking, learning that’s also hunting – you are hunting knowledge and you bring it home and share it with your people. The mind and the physical reflect each other – that’s yama.

The Australian coat of arms is meaningful to us, even though we weren’t asked to choose it. The emu is our teacher, wise and kind, and the kangaroo is like a warrior or a judge, strong and powerful. The nature of our land, our country, is reflected in this coat of arms. When I look at the English coat of arms, I see a lion and a unicorn. Do these animals come from your country? What does this coat of arms represent and what does it reflect about your country?

When I ask you to help me hunt the unicorn, will you understand what I mean?

Hunting the unicorn is a way to understand its ngurra kurlu, to try to understand the country and therefore to understand the people. After all, if you’re hunting something, you have to learn to think like the animal that you’re hunting. It’s a way to fit into the country and to feed on that country; that country nourishes you. That’s the most important skill you can have. It’s a skill to understand the prey, and to think like the prey. It’s something I never understood before. But now I do.

If you know how to reflect yourself, you can then reflect other people. Don’t try to do it back to front.

Featured image: Journey to Ard al Amal (The Land of Hope). Screenshot box & video installation. Impakt festival & exhibition. Image Pieter Kers

Foundland, Ghalia Elsrakbi (SY) and Lauren Alexander (SA), is a multi-disciplinary art and design practice based in Amsterdam. With backgrounds in graphic design, art and writing Foundland’s approach focuses on research based, critical responses to current issues. While moving around in advertising, printed matter, the Internet, and off line art spaces they dig up interesting stories about Disney, SpongeBob and defected soldiers.

Annet Dekker: Where does the name Foundland come from, or what does it mean?

Lauren Alexander: We started working together in 2009 and at the time we had worked on a project about being stateless, so Foundland seemed fitting. It is quite literally a way of thinking about how to found a land and to create a space that we could use as a platform for thinking about ideas with some kind of visual output. For us, space is related to political scenarios, and also to something virtual, online, all these different places that we inhabit.

Ghalia Elsrakbi: Foundland relates also to finding and discovering something new, looking behind something. We are very interested in speculation, we speculate about images and their meaning, in order to find something unexpected.

AD: What is your focus, what are you trying to find and tell?

LA: We want to tell stories in new ways, because by telling a story in a different way, especially related to subjects which are often seen in the media, you are offering an alternative perspective.

GE: The exhibition we just did for Impakt festival is a good example. With the installation Journey to Ard al Amal (The Land of Hope) we speculated how popular characters and animations, dubbed from Japanese to Arabic, or adapted from Walt Disney, play a valuable role in imagining heroes and villains. We were looking at a history of cartoons. This isn’t obviously political, but when seeing how cartoons are used in Syria and other places, interesting issues came up and we constructed a story that reflected on the current situation. We looked for connections between the way people see cartoon characters now and how they are embedded in childhood memories. In the end what we present is a kind of imagined picture of how things could be, maybe as an alternative to watching the news.

AD: Can you elaborate a bit, what images did you see and how did you (re)use them?

LA: In the installation we focused on this specific case study of the apocalypse scenario which is sketched in a cartoon series called Adnan and Leena in Arabic. In an earlier research essay Simba, the last Prince of Ba’ath country, we extracted images and characters from Arabic websites and speculate on appropriation by showing original images, before they were photoshopped. In a talk we did, we were also drawing connections to the way that Western cartoon characters are suddenly popping up in news footage, and how activists use cartoon identities on the Internet.

GE: Currently there is a full swing of the way Western stories are adapted. For example images of Mickey Mouse or SpongeBob are painted on walls in Syria. In the talk we question whether it is still Mickey Mouse that we see, the one that we remember from our children books, or if it means something else? We compared and related these images to the way such iconography is appropriated and used by both activists and ruling parties. The reuse of symbols and images and how sometimes historical moments are turned into something completely different is very interesting. Such findings are what we are really focusing on.

AD: There is also a long and popular tradition of autonomous animation in middle east, how does that relate to what you’ve been researching?

LA: Cartoons are very differently perceived in Syria, and also in South Africa, unlike in the Netherlands, they pose a huge threat to those in charge. For example the government is continuously suing political cartoonists like Ali Farzat in Syria and Zapiro in South Africa because their cartoons undermine existing power structures.

GE: There are indeed many artists who create political cartoons or satirical statements but with these Disney cartoons it was about finding the hidden story of an image. We recognise the cartoons from a Western perspective and the local one. By making connections and telling a different story we want to give a different perspective and a better understanding of what is really happening. Actually I grew up with Japanese Manga, but today Disney is everywhere. This is also political because in the time that Hafez Al-Assad was running Syria there was no American culture at all, when he died his son opened the country a bit for the Western market and you started to see American programmes. Nevertheless, everything is dubbed to Arabic so children don’t necessarily view it as an American production because it speaks their own language and sometimes stories and words are changed in order to better relate to Arabic countries.

LA: The connection to America is not obvious, what we found is that characters like SpongeBob and Mickey Mouse are simply friendly characters. They are your buddy, they help and like you.

GE: That is why they are used in this process of freedom fighting. ‘Your friends’ carrying the freedom flag and are used to create a kind of identification with the message that they want you to see. I mean, it is difficult to hate or not to trust these images because they are icons of friendliness. Whereas the image of a politician or some other hero who is telling a personal story can easily be damaged, a cartoon image is unbreakable. It appeals to children involved in the revolution. So, these images consist of many layers and bring up interesting questions. We aren’t looking for the true answer, because in the end we create our own story.

AD: Could you speak of a sort of universal populism or at least a continuing iconography?

GE: There are many different images, from the Lion and the Father and the Son, to things you see in public space, or images that people grew up with. These are all reused in a digital form and become part of the revolution. People tend to think of them as new images, but when you compare them to older ones, the original, it reflects very much the ideology of the regime. By putting them in a different context we try to force people to question the images and the stories.

LA: I remember that I was in South Africa when we were working on the fiction interview with a propaganda makers text and I had asked my mother to read it. She commented that ‘This is what the government used to say during apartheid, I recognize this’. I guess this shows quite a universal context. We are so used to advertisement and iconography that we don’t question it and tend to ignore the meaning.

GE: Yes, it’s not so different at all, propaganda still uses the same techniques, they have not changed and people fall for it. I think it’s very good to expose propaganda makers.

AD: What new context are you giving it?

LA: Up till now our work has been presented in a western context within the framework of festivals or art spaces.

GE: We wanted to show it to a Western audience, but now we also want to see how it will work when we go to Syria or the Middle East. This will be a challenge because we need to find a way to make that translation back again. We tried already a few times to publish texts for example, but the expectation is very different, stories are more direct and literal, you say exactly what you mean, not the way that we do it here which is reading between the lines.

AD: Is that also why you work in so many ways, from installations, to print, to presentation, to video?

LA: Yes, a lot of this is about experimentation with how things work. We often start from something that we have found online. We find a lot of information, which can be confusing, and then it is about finding the right moment, time and place to present it. Giving it all your attention to dig into an issue, know more and tell more.

GE: Each time we try to define the best way to present what we want to say. It is interesting to open and use the whole research process, it is not just about an end result that is presented. For example, now we are collecting a lot of defection movies from soldiers who are leaving the official army Syrian and joining the free army. What we notice is that the visibility of this free army is that it is only online, on YouTube. We are interested in how an identity of an army that exists on the ground and performs all kinds of operations, primarily takes place on YouTube. The videos of the defectors are almost like a physical performance of defection. We want to collect the story of it, to help people appreciate this image, why it was made, and think about what this means for us.

AD: Digging up memories and confronting people?

GE: When we started the cartoon project we noticed that people were hiding their identity online behind popular cartoon masks. It was really about how people used the Internet.

LA: We discovered that using the Internet is not always about the technical functions of connectivity, distribution, uploading and liking.

GE: If you look for example at how Syrians use the Internet, it’s really for emotional support. A few months ago there was no Internet in the whole of Syria, which was emotionally a big thing because people abroad couldn’t connect to people online and read their contributions. The revolution is nothing without these contacts. All of a sudden a Facebook campaign started called ‘Here is Damascus’. At first I didn’t understand it, but it turned out to be a reference to an event that happened in the 60’s in Cairo, while at war with Israel, the radios were cut off and there was no communication in the city. At that point the city of Damascus changed the name of their radio to ‘Cairo radio’. A political statement, like a re-enactment, happened now on Facebook. The Internet has all these different kinds of layers, of reflecting on history and bringing events to life.

See more Foundland work and updates at www.foundland.info