Featured image: Environmental Risk Assessment Rover – ERAR – AT (2008) Mobile, Solar Powered, Networked Installation Off the Grid, Neuberger Mus

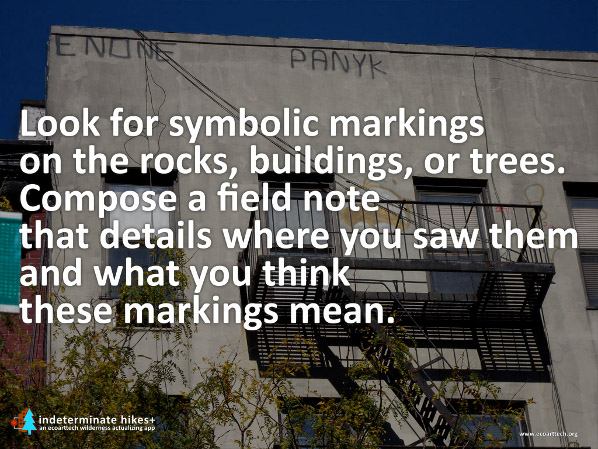

Refusing to regard technology merely as a tool, Ecoarttech expand the uses of mobile technology and digital networks revealing them to be fundamental components of the way we experience our environment. Their most recent work Indeterminate Hikes + (IH +) is a phone app that maps a series of trails through the city. IH + can be accessed globally, or wherever users have access to Google Maps on their mobile phones. After identifying the users’ location, IH + generates a route along random “Scenic Vistas” within urban spaces. Users are directed to perform a series of tasks along the trail and provide feedback in the form of snapshots generating an ongoing, open-ended dialogue.

But the experience of their work is primarily an encounter with technology. Since 2005, Leila Nadir and Cary Peppermint of Ecoarttech have been engaged in an artistic exploration of environmental sustainability and convergent media. By drawing our attention to the increasing replacement or mediation of physical experiences by technology, Ecoarttech challenge the widely reproduced distinction between nature and culture. They present their work in the form of videos, digital networks, blogs, performance and installations. Their early video-based work (Wilderness Trouble and Frontier Mythology) plays out a performative and ironic encounter with the natural environment as a historically constructed concept. In the summer of 2005 Ecoarttech made A Series of Practical Performances in the Wilderness (2005) a database networked performance in QuickTime (DVD and Podcast). The short clips document what Ecoarttech ironically describe as “the experiences of two New Yorkers embarking on their first four months in the woods“. Their objectives were nothing short of

…establishing a functional home without running water, electricity, or maintained roads; developing relationships with locals; un-learning the romanticization of nature while re-learning humanity’s dependence on the environment for survival; and researching the details of the history of the land and the surrounding area.

Sophia Kosmaoglou: The confrontation with the concept of “wilderness” appears to motivate much of your work to date. How did A Series of Practical Performances in the Wilderness begin and how did you fare?

Leila Nadir and Cary Peppermint: About eight years ago, we were very fortunate to acquire a primitive cabin on 50 acres of wild, wooded land, and the experiences we had there changed us completely. Each time we drove from NYC to our “camp” as the locals called it, we were immobilized for about 3-4 days, hardly able to move our bodies as our nervous systems screeched to a halt, adjusting to the quiet. We found a freedom in the woods that we couldn’t find the city – the freedom to take up space, to play, to be quiet, slow, and still. We were also amazed by how some people in the country could seemingly live more independently from bloated global economic systems, growing their own food, chopping their own fuel, harvesting solar energy. They interacted directly with the natural environment whereas we had spent our entire lives ecologically infantilized by overdependence on the industrial grid. We began spending several months at a time at our cabin in the woods: A Series of Practical Performances in the Wilderness is a document of our environmental adventures at that time. It was our first attempt at making art in remote, wilderness spaces. It was a sort of performance of ecological/cultural collision.

SK: How did this experience inform your subsequent work?

LN & CP: As we began to study environmental theory, we realized that not only does little “true” wilderness actually exist, the myth of wilderness was used to obscure the history of indigenous people living on the North American continent. Our own land, we learned, had once been a pasture and had been logged numerous times. Coming to terms with the fact that we hadn’t really retreating to “nature” was the focus of our video Wilderness Trouble which attempts to imagine a new kind of environmental ethics that includes urban and electronic spaces and modern networked culture. However, we still believe that wilderness provides a lot of imaginative potential. Amazement at sublime landscapes can provoke an emotional response that can be politically motivating, and we have tried to take advantage of that potential in our smartphone app Indeterminate Hikes +. By importing the rhetoric of wilderness into everyday life through Google-mapped hiking trails, the app attempts to inspire a sense of ecological wonder at usually disregarded spaces, such as city sidewalks, alleyways, and apartment buildings. We wanted to see what would happen if a walk down a sidewalk were treated as a wilderness excursion. What if we consider the water dripping off an air-conditioner with the same attention that we give a spectacular waterfall in the wilderness?

SK: There is a recurring effort in your work to question the opposition between environment and technology, which is usually accompanied by an ironic undercurrent in your narration and editing that acknowledges what you call “cultural collision”. In Google is a National Park and Nature is a Search Engine which is also part of a series of performances called Center for Wildness in the Everyday (2010), itself conceived as an ecosystem, you suggest that an “environment” is a network of relationships common to natural as well as technological systems, whether it is the ecosystem of a river estuary or Google. Do you see this as a sustainable analogy or a productive contradiction?

LN & CP: Part of what we find frustrating about a lot of environmental thought is that it either wholly rejects technology as the cause of ecological crises so our only solution is to go primitive or wholly embraces technological progress as a saviour, which often means we have to trust in corporate and scientific innovation to lead the way. We think there is another way. We see humans as essentially technical beings: human-animals literally cannot survive without technics. The U.S. military survival guide comes right out and admits that your situation is pretty hopeless if you are stranded in the wilderness without at least a knife. If technology is part of who we are – and we find Bernard Stiegler’s work helpful for thinking this through – then we have also evolved with technology. We are not the same sorts of humans as, for example, Leila’s great-grandmothers in Slovakia or Afghanistan a century ago. The question, then, is not, Yes or No to Technology, but rather, How do we engage technology sustainably and in a way that supports creativity and freedom? And if human beings are technical beings, relying on nature and culture simultaneously, is it even possible to distinguish between what’s natural and what’s not? Isn’t our sustenance dependent upon not only our biological needs (clean air, water and food) but also our cultural practices, beliefs, and imagination? This is why we find it essential to think about electronic spaces and digital technologies whenever we think about the “environment.”

The installation called Google is a National Park and Nature is a Search Engine, a work that is part of a series of performances called Center for Wildness in the Everyday commissioned by the University of North Texas. Our task for this commission was to create a networked artwork about the Trinity River Basin, the source of water for the Dallas/Fort Worth metroplex. In the image, the Trinity River looks like a space of natural refuge but the scientists we worked with there explained that the River’s flow is guaranteed only by the recycling of waste water at treatment plants. We wanted to create a work that juxtaposed this hidden constructedness of “nature” with the more obvious man-made Google – two processes or entities that we rely on everyday for our ecological sustenance: water management and online information.

SK: In 2008, you made the Environmental Risk Assessment Rover, a solar-powered module, which gathers and projects information regarding threats in the immediate environment. Although the ERAR is a sizeable aggregate of equipment that is carted around in a wagon, it seems to be the precursor to handy mobile phone apps. How does the ERAR work?

LN & CP: This project is part of our ongoing engagement with science – especially environmental science, which is also a focus of our 2009 work Eclipse. When you work at the crossroads of art and science, as we do, there is often an assumption that the role of the arts in this interdisciplinary exchange is to visualize or communicate knowledge produced by scientists. In contrast, ERAR asks what we learn when science breaks down – or when we use science to “interrupt” experience rather than to predict behaviours. The project arose out of our observations of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s handy yet arguably useless colour-coded terror alert system launched post 9/11 and our experiences with what risk theorist Ulrich Beck calls “science’s monopoly on truth”. Somewhere Beck writes that cows can turn blue next to a chemical plant, but unless science actually proves that the chemicals are the cause of the blue, nothing will be done about the situation. So although other forms of knowing might tell us that the plant is a public health risk, there is nothing we can do until Science “proves” a direct causal relationship. The Rover collects real-time risk data relative to its GPS coordinates, such as car or subway accidents, air pollution levels, violent crimes, proximity of superfund sites, and ground water toxicity, and then determines the aggregate local threat level through a 14-tiered alert system, ranging from “Holiday Shopping” and “Plastic Bags” to “Girls Gone Wild” and “Ask Your Doctor”. Obviously there is a bit of Dada in this work – but not Dada as simple chaos, as it is popularly invoked, but rather Dada as a shocking exposure of the limits of modern reason at the same time as it brings to the surface something that many of us have repressed from consciousness: the subliminal knowledge that there are ways of knowing the world that come from non-scientific experiences and observations. This tension between scientific expertise and everyday experience is also at play in our recent work #TrainingYRHuman.

SK: Have you considered launching it as a phone app?

LN & CP: The ERAR was our first truly mobile work, and it would probably make an interesting phone app – however, the public spectacle it creates is integral to the effectiveness of the work. Pulling around a wagon of technological parts that beams alerts onto the side of buildings is an art action and an effective conversation starter.

SK: Social networks and mobile phone app technology have rapidly become established means of communication and art galleries currently employ these technologies conventionally to replace audio guides. Your current work explores social networks and phone apps as potentially innovative platforms for art. Indeterminate Hikes + (2012) and #TrainingYRHuman (2011) can be accessed in diverse contexts and within everyday activities. They address a broad public, providing a plurality of entry points without necessarily being identified as art. How has the public responded to these projects so far and how do you hope to see them pan out in the long-term?

LN & CP: What motivates us most about working with new technologies is how they can be misused for unexpected purposes. Smartphones, generally, are deployed as devices of rapid communication and consumerism, to get you what you want and where you want as quickly as possible. Our app Indeterminate Hikes + reappropriates this mobile technology for a very different end, turning smartphones into tools of environmental imagination and meditative wonder. It transforms ubiquitous computing into an opportunity to notice the happenings occurring all around us in our local environments, to see sublimity in our backyards, alleyways, streets and neighbourhoods. Like many of our works, this is also a way to aesthetically pose an alternative to environmentalism’s frequent anti-media stance and to popular culture’s uncritical embrace of technology. We want to dream new ways of being without falling into prescribed behaviours or reactionary responses, whether with the food we eat, the technologies we interact with, or the environmental relations we imagine. Foucault’s call for the creation of “gay style” as an antidote to heteronormative culture has always resonated with us in our attempts to rethink dominant ways of being: what is the space of freedom in which one can intervene and express oneself, invent, upend? The mood after our public indeterminate hikes is often euphoric, and participant-hikers comment that they see the world anew. If enabled to be, smartphones can be a platform for chance operations, which, as Allen Kaprow explained, can create “near-miracles”: “when something goes ‘wrong,’ something far more ‘right,’ more revelatory, has many times emerged”. Our app can be used anywhere, any time, by anyone who has an Android phone or who attends our performances, so hopefully there will be many people misusing their smartphones and taking wilderness hikes in the wrong places for a long time. An iPhone version will be released this spring/summer 2012.

#TrainingYRHuman, a work-in-progress, is a participatory Twitter-based net artwork about the agency of animals who live with human-animals as well as an attempt to speak back to science’s monopoly on truth. In recent years, a burst of scientific research has illuminated animals’ behaviours, ethical attitudes, modes of cognition, and psychological awareness, yet usually when we read news of this work, we think: Were all those scientific tests really necessary to figure out that a certain animal species has feelings? Many people who work and live closely with animals already had abundant anecdotal evidence to support the fact that nonhuman animals have diverse personalities and creative problem-solving skills, that they think, feel, and are conscious. #TrainingYRHuman is a gesture toward bringing those anecdotes into the public record, toward creating a sort of oral history database of animal-agency stories that usually only circulate subliminally in our informal conversations. At the same time, it is a moment for human-Tweeters to imagine what it’s like to be a nonhuman animal, inventing unique ways to express oneself and meet one’s needs and desires in a human-dominated world.

SK: There are multiple registers and modes of address in your work and an ambiguity regarding the speaking subject. To an extent, this is because there are two of you, but you also construct voices and use various techniques to create further ambiguity around your agency. Can you elaborate on your strategies of collaboration and decision-making and how these relate to the tension and displacement that you create between the cultural and the technological, the physical and the digital, the artistic and the scientific, the collective and the individual?

LN & CP: Our primary collaborators are each other. Though we have a division of labour, we don’t have a conscious strategy of how we work conceptually, perhaps because we fell into making art together organically, out of collaborating on life. Ideas emerge for us out of an ongoing, sometimes unconscious, sometimes over-analytical, conversation that meanders through the digital/physical places we inhabit, whether we are in our studio or the kitchen. Whose idea it was to add orange juice to our hummus recipe or who came up with facilitating alter-wilderness hikes via smartphones is impossible to figure out. We are committed to an experimentality in process that involves interaction, exchange, exposure, and research that can take advantage of the energy created by blurring the lines between self and other. Proprietary works and the myth of the “genius” artist are detrimental to emerging modes of working, especially with regard to new media art production. Lately, animals have been a significant part of this process for us, shaking up our stale human behaviours and assumptions, especially the cows, sheep, and pigs we visited recently at the Farm Sanctuary in Watkins Glen, NYState, and the birds of prey we met through a local bird sanctuary called Friends with Feathers.

We can’t really say with authority whether our extended collaboration relates to the ambiguities of our artworks. However, we do try to welcome the breakdown of categories like digital, physical, human, nature, and animal as well as media, disciplinary, and environmental boundaries. What really is a “human”, and why has there been this historical obsession with somehow distinguishing humans from animals, as if we are somehow specially different from every other animate being on earth, more evolved and complex? As eco-critic Timothy Morton said recently, “According to evolution science, there are two things humans do very well, but they are a bit of an ego blow: throwing and sweating. Everything else is also done by nonhumans, including consciousness, feelings, art, tool use”. So we are simply sweaty throwers who think very highly of ourselves! It seems to us that the effort to hold tight to definitions, to reliable knowledge, or to the self blocks the more interesting conflations that happen (or are already happening) when we let categories slip away. Therefore, rather than try to determine, define, and predict in our art, we are more interested in staging fluid experiences that ask difficult questions and interrupt our sense of certainty. When assumptions fail, things fall apart, and we can’t depend on what we think we know, that is when our most creative thinking takes place. These are exciting, experimental moments.

Leila Nadir and Cary Peppermint founded Ecoarttech in 2005. They teach Video Art and Sustainability Studies at the University of Rochester in New York and they work with a range of institutions, including the Whitney Museum, Turbulence.org and the University of North Texas. They have exhibited at MIT Media Lab, Smackmellon Gallery, European Media Art Festival, Exit Art Gallery and the Neuberger Museum of Art. In June 2012, they will be artists in residence at Joya: Arte+Ecología, an off-the-grid residency program based at Cortijada Los Gázquez in Parque Natural Sierra Maria-Los Velez in Eastern Andalucía.

The Transborder Immigrant Tool (TBT) is a project created by the University of California at San Diego’s Electronic Disturbance Theater (EDT) 2.0/b.a.n.g. lab, and still evolving today. Here Ricardo Dominguez, co-founder of EDT (with Brett Stalbaum), Principal Investigator of b.a.n.g. lab, and Associate Professor in the Visual Arts Department at UCSD, discusses the project with Lawrence Bird. The interview includes input from other members of the collective: Brett Stalbaum, Micha Cardenas, Amy Sara Carroll and Elle Mehrmand.

Lawrence Bird: Simply put, the Transborder Immigrant Tool is a hand-held device to aid crossers of the Mexico-US border. As far as the cultural and political implications of this device, it’s loaded. But as a starting point, could you tell us a little bit about the technical side of the device?

Ricardo Dominguez: We began with the basic question: what ubiquitous technology would allow us to create an inexpensive tool to support the finding of water caches left in the Southern California desert by NGO’s? Our answer was that the sub-$20 iMotorola phone series could be made useful for emergency navigation. The early generation of the platform we targeted can be made reasonably useful in a better-than-nothing scenario. Meanwhile, later phone generations (that don’t yet cross our price barrier but are getting closer everyday) are already fully useful as practical aids without even a SIM card installed or an available network service. With proper use, the GPS performance of newer phones equals any GPS designed for desert navigation, and their used prices are falling. Moreover, GPS itself does not require service and has free global coverage, courtesy of the United States government. In an emergency scenario, we trust these later mobiles to direct a lost person to a nearby safety site. The TBT’s code is also available on-line to download at walkingtools.net, sans water cache locations, for any individual or community to use for their GPS investigations.

Lawrence Bird: It’s an interesting instance of technology intersecting with geography. You have referred to Donna Haraway’s work in your own comments on the intersection between “border crossing” and other forms of “trans”-being. Would it be accurate to see the TBT as a cyborg component; and if so, what does this mean for the relationship between technology, politics and poetics?

Ricardo Dominguez: Part of the TBT project is to call into question the northern cone’s imaginary about who has priority and control of who can become a cyborg or “trans” human – and immigrants are always presented as less-than-human and certainly not part of a community which is establishing and inventing new forms of life. When in fact these flowing in-between immigrant communities are a deep part of the current condition that Haraway’s research has been pointing towards – for us it is a queer turn in its emergence, both as unexpected and as desire. The investigation of queer technology and what this queering effect has been or might be is an important part of our conversations – especially via Micha Cardenas’ research. This gesture dislocates the techno-political effect with aesthetic affects that become something other than code: a performative matrix that fractalizes and reverses the disorder of things with excessive transbodies acting from the inside-out of those enforced borderless borders. These affects assemble new empirico-tran(s)cendental forms of multi-presence(s) incommensurable with the capitalist socius of the so called “immaterial” Empire. As the Zapatistas say, “we do not move at the speed of technology, but at the speed of dreams” – the heart of the trans-border-borg.

Lawrence Bird: As you say, that –borg is spatial. Do you do any work with professionals of space design – for example, you have mentioned elsewhere the architect Teddy Cruz, who’s done design projects and spatial analyses focused on the Mexico-US border, especially urban borders?

Ricardo Dominguez: We have not worked directly with any urban space designers, such as Teddy Cruz, who teaches here at the Visual Arts Department at UCSD as well – but we have learned a great deal about the nature of the border-as-design and auto-assemblage – especially from the Political Equator gatherings that he has been at the forefront in creating. But recently we were invited to create a gesture for Political Equator 3 that we really enjoyed and offered a poetic materialization of bringing TBT into Mexico: at 12:30 p.m on June 4th, 2011 the Transborder Immigrant Tool was walked into Tijuana, Mexico via an aquaduct from the U.S. side of the border by artist Marlène Ramírez-Cancio (a video of this event is embedded above).

Lawrence Bird: Does any of this work intersect with American fear over border permeability to terrorism? The criticisms of TBT seem to focus on economic migration but the reaction bleeds into fears over security.

Ricardo Dominguez: TBT does crisscross a number of these types of affective conditions that have been floating around the border since 9/11; or one might push it back to early formations of the Mexico/U.S. border. And yes, it intersects with the growing state of fear in the U.S. (and around the world) about immigrants dismantling the U.S. economy – which has always struck me as extremely ironic – since as we have encountered in these past couple of decades, neo-liberal economics on a global scale have done much more to dissolve the romance of the nation via a series of self-made economic bombs than any immigrant “invasion.”

Lawrence Bird: In fact your development of this tool has come at a significant personal cost. You’ve been accused of supporting illegal activity and misuse of public funds. You’ve been called a traitor. Your position at UCSD was threatened. Could you talk about that and where this situation stands today?

Ricardo Dominguez: The entire group of artists who are part of Electronic Disturbance Theater 2.0/b.a.n.g. lab working on the Transborder Immigrant Tool (TBT) was being investigated by UCSD and 3 Republican Congressmen starting on January 11, 2010. Then I came under investigation for the virtual sit-in performance (which joined communities statewide against the rising students fees in the UC system and the dismantling of educational support for K–12 across California) against the UC Office of the President (UCOP) on March 4, 2010. This was then followed by an investigation by the FBI Office of Cybercrimes. So, it was three investigations in total— and they were all seeking to find a way to stop TBT and threaten to de-tenure me for doing the very work I was hired to do and then tenured for. In the end all the investigations were dropped. I did agree not to do another virtual sit-in performance on the UCOP for four years, but the day I signed the agreement, a number of supporters across the nation did a virtual sit-in on UCOP again. One strange element about the agreement that they wanted me to sign without even giving me or my legal team time to look it over was that I would never speak or write about what had happened, create any artwork that might disturb anyone and refrain from an artivist performances. Of course I agreed to none of it.

Lawrence Bird: The vitriol in the attacks on you is remarkable, and disturbing: you received a great deal of hate mail and a number of death threats because of this project. You mention in your play Sustenance (published in Artists & Activists 12) that these messages “constellate into remarkable patterns”, form a chart as it were of the agitated contemporary discourse over immigration, security, and national purity vs. liberty. It’s significant that you’ve built a play around this. Do you see the political and popular response to your project (you refer to it as “viral reportage”) as part of the TBT’s performative aspect?

Ricardo Dominguez: Part of the history of the Electronic Disturbance Theater 1.0/2.0 and b.a.n.g. lab (stands for bits, atoms, neurons and genes) at CALIT2/UCSD has been to develop works that can create a performative matrix that activate and take a measure of the current conditions and intensities of power/s, communities and their anxieties or resistances. So, for us the U.S. Department of Defense launching “info-weapons” at us for a virtual sit-in on September 9th, 1998 or the current confluence of “viral reportage” and the affective contagion of hate about the project that followed are all part of the performance – of course we would much rather the hate-mail never occurred – dominant media is bad enough to deal with. The aesthetics of working in the zones of post-contemporary artivist gestures cannot really escape these types of encounters; it is part and parcel of the patina of our work. But, we also feel that the hate mail or the general fear of losing national purity is co-equal in importance with the poetry that they were attacking. In fact Glenn Beck, an extreme right wing pundit on the Fox News Channel, attacked not only TBT’s use of poetry, but that the poetry itself had the power to “dissolve” the nation. The performative matrix of TBT allows viral reportage, hate-mail, GPS, poetry, the Mexico/U.S. border, immigrants, to encounter one another in a state of frisson – a frisson that seeks to ask what is sustenance under the sign of globalization-is-borderization.

Lawrence Bird: Can you tell us a little more about the poetry that accompanies the guidance system? How was this chosen, what does it concern? How do you envision the poetry developing as the project continues?

Ricardo Dominguez: Electronic Disturbance Theater 1.0/2.0 has always been invested in experimental poetry as part of its gestures – from the found poetry of the “404 file not found” of our ECD performances in 90’s to the border hack actions with the Zapatista Tribal Port Scan in 2000 on U.S. Border Patrol servers, where we would scan and upload Zapatista poems that we had written into their servers. When we started to develop TBT it became important once again to have a core impulse of the gesture. In 2008 I asked my partner, Amy Sara Carroll, who is an experimental poet and scholar, at University of Michigan, Ann Arbor – one of the areas of her research is on art and Mexican/U.S. border. She thought that TBT becoming a geo-poetic-system (gps) could expand the frame of experimental poetry and artivism. She then began to work with us and established two geo-poetic tracks – one conceptual and the other an echoing of desert survival manuals in multiple languages, which speaks to the multiple borders that are crisscrossing the planet and the multiple languages that are crossing Mexican/U.S. border via immigrants. Here is Amy speaking about TBT:

“…my collaboration with Electronic Disturbance Theatre (EDT) on the Transborder Immigrant Tool…(is) imagined as a global project under development, my own involvement in that ongoing process is linked to the question of what constitutes sustenance in the quotidian of the conceptual, on the varied musical scales of the micro- and macro-. For, often—rightly enough—conversations about crossing the Mexico-U.S. border refer to disorientation, sun exposure, lack of water. The Transborder Immigrant Tool attempts to address those vicissitudes, but also to remember that the aesthetic—freighted with the unbearable weight of ‘love’—too, sustains. A poetic gesture from its inception, the Transborder Immigrant Tool functions, via the aspirations of such a dislocative medium, as dislocative media, seeking to realize the possibilities of G.P.S. as both a ‘global positioning system’ and, what, in another context, Laura Borràs Castanyer and Juan B. Gutiérrez have termed, a ‘global poetic system.’ The Transborder Immigrant Tool includes poems for psychic consultation, spoken words of encouragement and welcome, which I am writing and co-designing in the mindset of Audre Lorde’s pronouncement that ‘poetry is not a luxury.’ … speaks to the Transborder Immigrant Tool’s overarching commitment to global citizenship. For, the excerpt, itself infused with the ‘transversal logic’ of the poetic, acts as one of the Transborder Immigrant Tool’s internal compasses, clarifying the ways and means by which I and my collaborators approach this project as ethically inflected, as transcending the local of (bi-)national politics, of borders and their policing.” http://bang.calit2.net/xborderblog/?tag=poetry

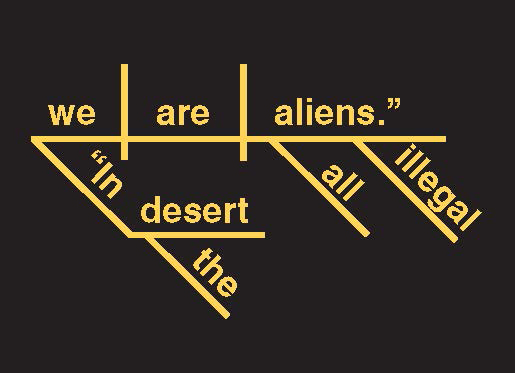

Here is a poem that made Glenn Beck extremely angry:

TRANSITION

(song of my cells)

Gloria Anzaldúa writes, “We have a tradition of migration, a tradition of long walks. Today we are witnessing la migración de los pueblos mexicanos, the return odyssey to the historical/mythological Aztlán” (1999 [1987]: 33). The historical? The mythological? Aztlán? It’s difficult to follow the soundings of that song. Today’s borders and circuits speak at “lower frequencies,” are “shot through with chips of Messianic time.” Might (O chondria!): imagine the chips’ transliteralization and you have “arrived” at the engines of a global positioning system—the transitivity of the Transborder Immigrant Tool. Too: when you outgrow that definition, look for the “trans-” of transcendental -isms, imperfect as overwound pocketwatches, “off”-beat as subliminalities (alternate forms of energy which exceed Reason’s predetermined star maps). Pointedly past Walden-pondering, el otro lado de flâneur-floundering—draw a circle, now “irse por la tangente”—neither gray nor grey (nor black-and-white). Arco-iris: flight, a fight. Of fancy. This Bridge Called my Back, my heart, my head, my cock, my cunt, my tunnel. Vision: You. Are. Crossing. Into. Me.

Here is a beautiful video version that Micha Cardenas and Elle Mehrmand did of the poem: http://bang.calit2.net/xborderblog/?p=49

In the strongest possible sense poetic practice has emerged in TBT that is co-equal with Brett Stalbaum’s idea of a “last mile” tool and his development of the code necessary to have it work. In fact we also think of the code-as-poetry as well – an expansion of codeswitching – literally.

Here is one of the desert survival poems:

En última instancia, muchos dirán que

la naturaleza establece el estándar de

la neutralidad. A diferencia de los seres

humanos, la naturaleza no hace lazos

de lealtad con la nación, la familia, los

negocios o la religión. Usted sabe bien

que el mayor peligro que enfrentará en el

desierto puede no ser el clima o el terreno.

Habrá quienes no tengan en consideración

su bienestar. Los rescatistas tienen el

compromiso de ayudar a quien lo necesite;

exíjales cumplir esa promesa. No confíe su

vida a nadie más, a ningún extraño.

All them are available in multiple languages to the user on TBT.

Lawrence Bird: How do you navigate the legal issues? Did you have a strategy in place ahead of time for dealing with these, or have you had to deal with them ad-hoc? Does your strategy/defense link up at any level with that of apprehended border-crossers?

Ricardo Dominguez: We are not attempting to navigate “legal” (national or international) issues – but we are trying to establish a reconfiguration of the border and immigration in terms of what we are calling transborder justice – the question of a “higher law” doctrine that David Henry Thoreau established in On Civil Disobedience. Also, in a more speculative manner as artists we see TBT as still in the process of becoming – it is still shape shifting and performing itself into potential spaces of use and poetics. TBT is border disturbance art that constitutes a visible geo-aesthetic/geo-ethics gesture against the boundaries and borderless borders that are crisscrossing every single body on the planet – we call for a geo-aesthetics that starts at the nanoscale and reaches to the GPS (Global Position System) grid system that floats around the planet, we call for a geo-aesthetics that connects both the human and the inhuman, geography and ethics, we call for a geo-aesthetics that crosses into and dislocates the smooth space of geo-spatial mobility with ethical objects for multiple forms of sustenance. We live in a world where only goods and services have rights to cross borders – a world that is a chaosmosis of markets that demand global exchange and aggressive state social filters. We need a geo-aesthetics that can construct ethical and performative complexities for the new earths to come, that can touch new geographies for new bodies – transbodies with transborder rights – artwork that can function as a geo-philosophy for bodies that are flowing as transborder bodies across all the borders the world – a flowing-trans-nation the planet cannot survive without.

Lawrence Bird: Have you considered applications of the TBT more globally, in Europe for example, or the Canada/US border, which has its own tensions relating to indigenous sovereignty? Or would this take it out of the specific politics you want to focus on?

Ricardo Dominguez: We imagine TBT’s code and gesture as open to use on multiple borders and that it is not bound to just the Mexico/U.S. border. One way that we have attempted to promote this possibility is by making the code available to anyone or any group at walkingtools.net.

Lawrence Bird: How extensively has your system been used on the Mexico/U.S. border? Or is it primarily rhetorical so far (it’s certainly been successful that way). How is it coordinated with others’ humanitarian efforts for border-crossers?

Ricardo Dominguez: On a very practical level our work with NGO’s has been focused on working with groups in Southern California who have established networks of water caches for immigrants crossing that area of the border – specifically Water Stations Inc. and Border Angels. Water Stations Inc., the longest running NGO working on this issue, has been very open to helping us test TBT and has also offered us extremely important insights into what the real conditions on the ground and what problems immigrants are facing. We recommend that if folks have funds to donate to these groups – please do. They were very wary of us at first – but they have now become much more supportive – especially because of the work that Brett Stalbaum and his partner, artist Paula Poole, have done in with them beyond TBT.

On the rhetorical end of the gesture much of the work that we do at b.a.n.g. lab is to start our research as a politics of rehearsal, a rehearsal of politics, as part of our art practice – to create an aesthetic of minor-signals and lower-frequencies…”like physics, aesthetics is a science whose primary object is signals, the physical materiality of signs….”– to quote from a recent tweet by Jussi Parikka. To manifest a type of science of the oppressed or engineering of the oppressed that imagines creating speculations that automatically, conceptually, begin to disturb not only the lines of thinking that criss-cross not only our bodies, but the ecologies of the Americas, and certainly the globe. And, so it becomes necessary to create these speculative disturbances that can allow one to think about another possibility, another impossibility, that these systems both manifest and, at the same time, call for an “anti-anti-utopian” potentiality, so that the engineering of the oppressed, the science of the oppressed, is about rehearsing the fictions that will then become realities. Our work in one sense is simply a gesture of “plagiarism”—a cutting and pasting of what is already an assemblage or a system that exists because immigrants are crossing multiple spaces around the world and GPS is everywhere in our cloudy global Empire. And so TBT itself is an attempt to create the multiple layers that manifest the social frictions, the speculative fictions, the rehearsal of politics, and of a counter-machine aesthetics—a machine of difference that can only really be performed by more than the multitude, if you will, to interrupt what Mary Pat Brady calls the U.S/Mexico border, “a state-sponsored aesthetic project.” We can see how these speculative gestures do create social responses on a global scale.

Lawrence Bird: TBT doesn’t just provide a map and way of locating oneself, it offers directions to various support services – where to find water, medical help. How are such safe sites managed and their position made public without making them vulnerable to border patrols? Are there any ethical issues involved here?

Ricardo Dominguez: The water cache sites are already well known by the U.S. Border Patrol, Homeland Security and anyone else who cares to take a trip along the Anza-Borrego desert in Southern California – in fact they have large flags signaling their locations. So TBT at this point is only doing one thing – offering the location of these known and established water caches – as a last-mile safety tool and nothing more. The cell phones we are using are not robust enough for anything else – now as more cheap high-end phones come on the market TBT will be able to offer more on multiple levels. So the ethical questions about TBT on the U.S. side of the border are not as complicated as those on the Mexico side of the border: these are questions about how TBT would interact with the coyote networks, would it be just one more material burden to those crossing, how does the extreme violence of the narco-war shut down the abilities of NGO’s etc., to work on distributing TBT with us – these questions seem much more important in terms of the ethics of the project – would it do more harm than good? Or is it a gesture that would offer a way out for some immigrants from the violence of these dangerous networks that they have to deal with in order to cross? At this point due to all last year’s issues we have not been able to formally present TBT to the immigrant communities preparing to cross to have a dialogue about these questions – but we are hoping to move forward with these encounters – sans any further investigations.

Lawrence Bird: And how has TBT been taken on the Mexican side – what is it’s perception on the part of Mexican citizens, politicians, media? I’m curious how their reaction compares to the response on the American side, which approached violence.

Ricardo Dominguez: It is difficult for us to access Mexico’s response to TBT in relation to coyote economies or the narco-war on the border – these are zones that we have not attempted to have conversations with or have correspondences with. But EDT 2.0 is concerned about how TBT might function within or alongside these violent enclosures that immigrants have to deal with on multiple levels. We do not want TBT to become an attractor for immigrants who are already targets for these groups. But what we can say is that Mexico’s dominant media and alter-media networks, from Tijuana to Chiapas, have been very responsive and supportive of TBT. One of the first awards TBT received was in 2007 from the new media arts festival Transito_MX, who awarded TBT the “trans-communities award,” and the award was handed to us by a representative of the U.S. Embassy in Mexico. So at this time the response to TBT is both unknown and known. Another concern that we have and that we hope to be able to have a better sense of by the end of the year is how the design works for immigrants, and to what degree do they consider it useful as an art work and “last mile” safety tool – this will be done via workshops with potential immigrants in Tijuana, Mexico. Also one of the core questions we will have, based on all the materials that immigrants leave in the desert while crossing – the heat and difficulty of crossing call for dropping as much away from the body as possible, from money, to telephone numbers, to pictures of loved ones, etc. – is one more thing to weigh one down really necessary? These are EDT 2.0’s concerns at this time in relation to the border on the Mexican side.

Lawrence Bird: You mention that what drives border crossers is a hope that amounts to a “hope for the unknown”? Could you elaborate on this? At any level do you see a contradiction between this and the technologies of transparency, like GPS?

Ricardo Dominguez: The radical gesture of transparency was extremely important to EDT 1.0 in relation to Electronic Civil Disobedience as theory and practice and it still is in relation to the general distribution of TBT – who were are, where we are, and why we are doing it. But we are also very interested in the notion of translucency as an aesthetic possibility for TBT that functions to dislocate the readability of GPS (Global Positioning System) and gps (a geo-poetic system) – a minor form of the technology that is no longer bound to the total vision of GPS that is now embedded in almost everything. This translucency functions as a single-bounce GPS that initiates the database of TBT and then shuts off – thus making triangulation impossible – unless the user decided to turn the function on during the crossing. TBT’s gps creates an aesthetic disturbance that dislocates GPS as a transparent device and instead offers a navigational translucency of the “last mile” with hope-as-sustenance as its guiding wave-point.

Lawrence Bird: In Sustenance you refer in passing to Baudrillard’s “desert of the Real”. It’s a compelling way of looking at the border desert where migrants are abandoned in their pursuit of the American fantasy. But adopting a perhaps more humanist attitude, would it be remiss to recall Saint-Exupéry’s words that “Ce qui embellit le desert…c’est qu’il cache un puits quelque part.” / “What makes a desert beautiful is that, somewhere, it hides a well.” Perhaps based on that juxtaposition, how would you place your project in relation to the tension between poetry, activist politics, and humanitarianism?

Ricardo Dominguez: TBT is still in a (gps) process of becoming – it is still shape-shifting and performing itself into potential spaces of use for activists and expanding the frame of dislocative poetics. TBT is border disturbance art that constitutes a waterwitching tool that indeed crosses the desert of the Real, the hard simulations of the border which seek to target and kill. It offers another possibility – with the anti-anti-utopian offer of the desert’s “beauty” that you are keying into the conversation. We imagine that this gesture echoes practices that fractalize the desert’s geo-aesthetics as: artivism, tactical poetries, hacktivism(s), new media theater, border disturbance art/technologies, augmented realities, speculative cartographies, queer technologies, transnational feminisms and code, digital Zapatismo, dislocative gps, intergalactic performances, [add your own______].

“You Are Now the Electronic Man” are the words that appear before even opening the website for The Electronic Man, a project initiated by Salvatore Iaconesi and Oriana Persico of Art is Open Source (AOS) and FakePress. And by becoming part of The Electronic Man, sharing your emotions as they become linked through QR Codes and help to build the frame of The Electronic Man, you are participating in a real time global performance.

This real time global performance relates to conceptual experiments by AOS and FakePress, in remixing reality and creating new sensual experiences with technology. The email interview took place after their recent exhibition at Furtherfield’s gallery in London, called REFF – REMIX THE WORLD! REINVENT REALITY!, which happened during February, March 2011, and during their current project The Electronic Man. We discuss AOS’s ideas and intentions, regarding their activities of performance and use of technology, and their methods of engagement with anthropology and biology.

Renee : The Electronic Man is quite an ambitious project. What inspired you to begin building the Electronic Man?

Salvator and Oriana: The Electronic Man is actually a very simple project (if quite a difficult one in terms of “making it happen”) as it is a direct poetic interpretation of a theory by Marshall McLuhan that goes by the same name. We decided to take the famous statement by Marshall McLuhan quite literally and transform it into something that is really happening in the world: “Electronic man like pre-literate man, ablates or outers the whole man. His information environment is his own central nervous system.”

What we wanted to do was to make our statement for the centennial of McLuhan’s birth, but to avoid the form of the “conference presentation” for it, and to show in a powerful way how the ideas expressed by McLuhan are really taking place in the world which we experience every day. So we decided to produce a performance, a global performance.

With the wonderful support of Derrick de Kerckhove, and of the MediaDuemila magazine (and the Associazione Amici di Media Duemila and the Osservatorio Tuttimedia, and the Department of Communication and Social Research of Rome’s University “La Sapienza”, who were organizing the official event for the centennial in Rome, under the fundamental guidance of Maria Pia Rossignaud) we were able to make it happen and everyone involved was really happy to include this experience in the official celebrations.

Renee Carmichael: I find the methodology behind this project really interesting. From what I understand it’s about going beyond the analogue vs. digital debate and really going in between and just experiencing and experimenting. Do you think this methodology is important to use in today’s world? How and why might this be so?

Salvatore and Oriana: We are living in a really complex scenario, complex, fast and ever changing. Digital technologies and networks are starting to pervade our analogue reality, transforming it and opening up entirely new possibilities. There are forms of (digital) interaction that are starting to be widely accessible from physical space. These forms of interaction are really peculiar as they allow for a transformation of (physical) reality, making it interactive, reinventing it, remixing it, and adding content to it. The world itself becomes a performance and a very specific form of performance: involving remixes, mashups, recontextualizations and reenactments as its main practices. This has drastic effects, not only as our reality multiplies and reshapes, but also attitudes, perceptions, skills, knowledge and approaches of the people involved change. In this process methodologies, practices and theories remix as well, bringing forth various possible scenarios, in which collaboration practices emerge as the only viable way to perform significant actions.

So, in this scenario, “life, the world and everything” is turning into a multipliable, performative environment in which the only way to, actually, perform in a significant way is to collaborate across cultures, skills, theories and methodologies. This brings forth a change to our sensorial environment, meaning that when ubiquitous technologies are involved, we instantly gain new senses, new sensorialities and sensibilities. Just like with the mobile phone, when it doesn’t catch the network, we move, naturally and without thinking about it, to a place that has better network coverage, in a way that is neurologically similar to the way in which we move our hand away from fire when we feel the heat: it is a real sensibility, an additional sense.

Mixing these two aspects (the forming of a multilayered, collaborative, read-write reality, and the emergence of these new senses), describes a situation that is almost exactly the one presented in the question: experimentation, as in performance and as in science, this new science that traverses disciplines, theories and approaches; and experience, meaning you are actually able to build a new experience of the world that is sensorial and, most important of all, writable.

This is also a good description of the shape that the term “conflict” is assuming: a continuous process of movement and traversal, in which you transform a part of reality (as in augmented reality) adding new meaning and imaginaries to it, in a performative action that unites activism, art, science, design and communication, and that transforms and is transformed really fast, at the pace of the evolution of technologies and networks.

Renee: I read that this project can help us experience and reflect on our place in the world through the external. Do you think the relationship between the individual and the external takes a new shape throughout this project? How might it be understood in the larger ideas and theories of the Electronic Man?

Salvatore and Oriana: The Electronic Man is about the observation and exemplification of something that is already happening in the world. It speaks about interconnection and our renewed perception of space, time, body and relationships. Technologies helped us reshape these concepts completely. We are never in a single place now; we are everywhere, anytime and with lots of people all at the same time, using multiple identities, both voluntarily (mobile phones, ubiquitous networks..) and involuntarily (CCTV, social networks spying on us..). So all these definitions change radically: private and public space, gender, relationship, message, privacy, work and free time. We wanted to make this change explicit. In this change: public and private completely restructure! This is also why we decided to use the “emotional” dimension as a narrative: emotions are thought to be a private, intimate part of our lives, but now they are the object of public observation through what we do in the digital realms, for the new forms of economies that are developing, focusing on attention, reputation, awareness and more.

Renee: Although the Electronic Man allows us to experience sensually, it still creates finite points of data through the connections between a place and an emotion. What do you think is the relationship between the sensual impact of the project and the data it produces? How does the data fit into the idea of creating a new ‘global digital sense of our bodies’?

Salvatore and Oriana: This is a very complicated question! We chose this approach as a starting point. We are using a classification of emotions which is very basic (designed by Plutchik in 1980) it works really well across different languages (we are currently using 29 languages for our performances, to address as much of the world as possible). But this point that is described in the question (freeing the modalities of data, augmenting the degrees of freedom which we can express) is one of the focal points for expansion in the next steps. There are solutions and approaches which we are finding suitable to confront these issues with, and they are all related to adding degrees of freedom in what you “release to the public”: transforming artworks into free frameworks for expression that can be freely used by people. This transformation from artwork to framework is something that is happening all over, and it has to do with P2P culture and free software. This is why we release all the software and hardware (and methodologies) we use in our performances under free licenses: because the next step of each performance is made by the people taking the tools in their own hands and creating their own forms of expression and action, their own additional layers of the world.

Renee: In a related note, this new form of being that the Electronic Man creates cannot be completely separated from the world and systems it exists in already. It seems that the questions that often arise around this project are in terms of how it can be used within other appropriations. How do you see the future of this project in terms of the various appropriations that it may have and in terms of your own intentions for the project?

Salvatore and Oriana: As we said: we’re always in beta version. These processes are nomadic, temporary, and unstable. Ideas, software tools, concepts, hardware, practices and approaches are in a continuous state of remix: each time we speak to anyone, or even as we’re writing this, the performance changes and upgrades to the next version. For example we can look at the recent augmented reality interventions that have been taking place all over the world and, just a few days ago at the Venice Biennale: there has been a very fertile discussion building up during the last two years, on the idea that these technologies allow you to “squat” reality, and add new meanings and new degrees of freedom to it. This is why we created a project called Squatting Supermarkets a couple of years ago. This discussion is producing actions: appropriations, performances, re-usage of terms, words, sentences, new forms of activism, and new forms of art. We’re really happy that this is taking place, and we see all this as a wider form of performance in which everyone interested can be involved.

Renee: I can’t help but see a relationship between The Electronic Man and a sort of modern day Frankenstein. Would you like to comment on this relationship?

Salvatore and Oriana: We will answer this question using an answer that our dear friend prof. Massimo Canevacci gave to a question during a TV show in Italy: “This is a wonderful question, and I am deeply convinced that western cultures produced these really heavy mythologies around Frankenstein, the Golem, and arriving to a movie, a very nice one, like Blade Runner, taken from a novel by Philip Dick.

I am certain that this system, this dualism between technology and body, between organic and inorganic, between nature and culture, is finally over, in a liberating way. There are researches in which the concept of cyborg constitutes a perspective that is capable of liberating enormous possibilities. Therefore our bodies become progressively more entangled with technology all over literature, technology, anthropology, and biology.

Thus I sincerely hope that this enormous mythology, this terrifying myth of the Frankenstein, will finally end, once and for all, and will peacefully retire; and that new forms of cyborg will emerge and free themselves, to produce new free forms of expression.

Renee: Finally, any further issues, ideas, thoughts you would like to add?

Salvatore and Oriana: Yes!

The Electronic Man is a global performance! And it becomes useful if lots of people participate (and, by the way, participate by doing even simple things such as attaching some of the Electronic Man stickers around and sending us a picture, and you’ll find yourself and your work advertised whenever we exhibit the work: for example at the MACRO museum in Rome there is a full wall dedicated to the people that are helping us out, including their bios, pictures and links) But, most of all, it becomes useful if lots of people actively grab technologies, methodologies and concepts and actively build their own performative world, possibly sharing the results with everyone else.

So we strongly invite everyone out there to request the software, (it will be published on our sites as soon as we have some time to prepare a proper sharing mechanism, but you all can have it before that by simply asking) and to imagine other disruptive ways of using technologies to create free, accessible, inclusive spaces for communication and expression.

We will support you all in that as much as we can.

The Electronic Man at ADD Festival, MACRO Testaccio, Rome contemporary art museum, view video on Youtube.

Featured image: Photograph of a creative experiment on more intelligent modes of inhabiting the planet

Open_Sailing‘s biggest achievement is perhaps to have turned our future into an open source project. Led by a group of enthusiasts, gathered around the idea of “we don’t know what will happen, but together we can invent our future and cope”, the project puts forward a very ambitious, action-driven, experiment-led, way of thinking forward. After meeting with the founder of the project, Cesar Harada, Open_Sailing proved to be a much more complex enterprise than I originally thought.

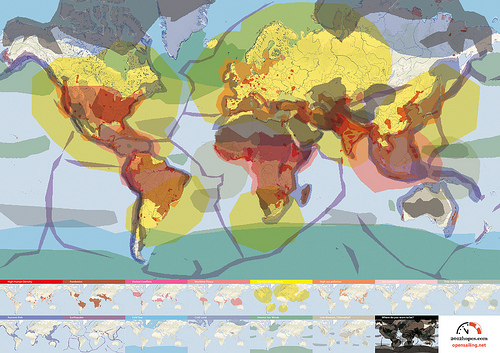

Initially the project started by mapping threats, the idea being that threats can produce something else than fear. Indeed Cesar Harada, was decided to turn threats into design constraints. This constitutes an interesting methodology to deal with the current climate of fear. The exploitation of threat has become the standard procedure to stabilize a permanent state of emergency. Mobilising virtual threats, states acquire exceptional powers that facilitate the implementation of ever more pervasive measures of control. The current case of swine flu is the last of a long list of exercises of mass modulation of fear. War on terror is the paradigmatic one. On the other hand, and following the warnings of the Maya calendar, all sorts of popular tales for an apocalyptic 2012 have started to populate the planet.

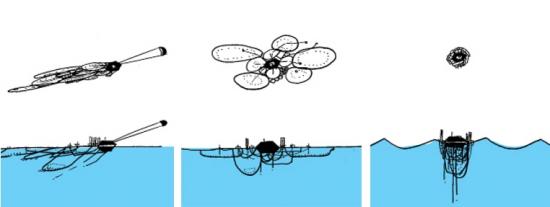

The role of Open_Sailing is to function as a catalyst that channels all this energy into the production of a better future. In short, its role is to transform fear into hope. Certainly this functioned as a strong attractor for new collaborators and soon the team started to grow. After putting together large amounts of real-time data about all sorts of dangers such as tsunami, terrorist attacks, nuclear accidents or pandemics, it became clear that the potential safest spots on earth were mostly located at sea. That led to the idea of designing the infrastructure necessary to inhabit those spots based on the concept of ‘Open Architecture’. Fear had been successfully turned into an active force unleashing the creative process. Inspired by this initial concept the Open_Sailing team started a very intense process of scientific, technological, architectural and artistic research that resulted in a first prototype awarded at Ars Electronica: Open_Sailing_01.

“A drifting village of solid and comfortable shelters surrounded by flexible ocean farming units: fluid, pre-broken, reconfigurable, sustainable, pluggable, organic and instinctive.” [1]

This drifting village, which is about 50 metres in diameter and can host four people, is designed to respond to its environment, being able to become compact and endure severe weather conditions, and spreading out to harvest in calm situations. Open_Sailing_01 was supposed to set sail last May 2009 but mis-coordination in the production with Ars Electronica delayed the plan. In the meantime, small intermediary prototypes of different modules are being built and tested constantly, but the Open_Sailing team hopes to put together the main modules of the International_Ocean_Station for general testing by the summer 2010.

One other important thing that came across in the interview with Cesar Harada was how soon after Open_Sailing was set in motion, it became clear that the project was not only about escaping the problematics of our society. It was definitely not an idealistic utopia happening elsewhere and starting a world from scratch. Rather than an exercise of escapism, they realised that the idea of inhabiting those sites where there is no threat had become an experimental laboratory where to grasp the future. Indeed Open_Sailing is very much about finding ways to face and deal with the very problems of our world.

“Be it overpopulation, global warming or energy conflicts, we are living in a time where ‘Apocalypse’ beckons. We need to collectively invent and spread bootstrapping DIY technologies for the forthcoming challenges, not only to survive but to re-invent how we inhabit this planet.” [2]

This became particularly obvious when the team flew to Morocco to try out some live-saving structures. Between the coast of Morocco and the Canary Islands in Spain hundreds of illegal immigrants die every year at sea. A high-seas permanent shelter would provide a low cost life-saving facility for the migrants.

This particular instance is also paradigmatic of the way in which experimentation is carried within the project. Future thinking is developed through material instantiations. This very characteristic process of design and engineering disciplines gives Open_Sailing an exciting palpability, a materiality, a commitment with actualisation that accounts for its potential to bring about real change. Commitment with results drives the project away from the artistic disciplines, but the poetics of the project undeniably brings them back together. A project that in a year of development has acquired such a level of complexity necessarily had to go through a very intense and accelerated process of conceptualisation and experimentation. And there comes the figure of the enthusiast, an experimental survivalist who is willing to take a plane the morning after an idea has come up to participate in a military training testing life-saving technologies.

Even more interesting is perhaps how this enthusiasm becomes contagious and the project starts to work as a truly open source venture. Open_Sailing becomes a powerful autonomous entity that keeps bringing people in a dividing itself into labs. Each new lab engages a whole new group of contributors, with a new set of preoccupations and hopes. The project proves to be definitely not about the implementation of a master plan or utopian blue print, but an example of how open source can literally be applied to the construction of alternative worlds. Within these labs we find different experimental research projects focusing for example on mesh networking; pollution, climate and natural reserve monitoring; sustainable aquaculture in high seas; or energy autonomous systems that generate electricity through wind, sun or wave power.

Now, there is of course the problem of co-option. The research being done is a very useful material with infinite commercial and even military applications. But perhaps this is not something that compromises the success of the project. Rather, its value lies in its capacity to encourage people to co-design their own futures. It is more about joining people that want to create than attracting those that want to buy. Surely, it is the process of creation of alternative that’s been set in motion that is truly significant, even more than the technologies being produced. Furthermore, Open_Sailing manages to reverse the process of co-option, the same way it reverses the effects of threat. Collaborators turn to scientific institutions, corporations, military research, as a useful resource, and then open up the knowledge acquired. This is not a new ‘green design’ product for the consumerist society, it is a spark for a collaborative rethinking of the world.