Featured image: Image from When Drones Fall From the Sky, by Craig Whitlock, Washington Post. [link]

At 0213 ZULU on the 2 March 2013, a Predator drone, tail number 04-3133, impacted the ground 7 nautical miles southwest of Kandahar Air Base, Afghanistan, and was destroyed with a loss valued at $4,688,557.[1]

On the 27th March 2007, a crashed spy plane was discovered by Yemeni military officials in the southern province of Hadramaut, along the country’s Arabian Sea coastline. The following day, Yemen’s state media identified the plane as being of Iranian origin, and that it was yet another example of an Iranian provocation at a time of high diplomatic tensions between the two countries. It was three years later, upon Wikileaks’ release of the so-called Cablegate archive, that a US Embassy cable revealed the “Iranian spy plane” was in fact a “Scan Eagle” drone. The drone was remotely piloted from the US Navy’s USS Ashland which was patrolling the Arabian Sea as part of an international counterterror task force. The United States Military was not “officially” conducting military operations in Yemeni territory at the time, and had not sought permission to conduct operations in the country’s airspace.

The discovery of the crashed drone could have posed a difficult political problem for the US to solve. However, in the cable, the official makes it clear that Yemen’s President Saleh had been keen to reach an agreeable deal with the Americans and apportion blame on a convenient third party — Iran. The cable states:

“He could have taken the opportunity to score political points by appearing tough in public against the United States, but chose instead to blame Iran. No doubt focused on the unrest in Saada and our support for the transfer of excess armored personnel carriers from neighboring countries (reftel), Saleh decided he would benefit more from painting Iran as the bad guy in this case.” [2]

By 2007, aside from occasional reporting in the media and among some activist circles, there was little public awareness of the US drone program. In fact, the program was not officially acknowledged on-the-record by a US government official until 2012. This official was John O. Brennan, then Counterterror Advisor to Barack Obama, and the momentous occasion was a speech at Washington DC’s Wilson Centre—a “key non-partisan policy forum for tackling global issues through independent research and open dialogue”.[3] Brennan states:

“So let me say it as simply as I can. Yes, in full accordance with the law—and in order to prevent terrorist attacks on the United States and to save American lives—the United States Government conducts targeted strikes against specific al-Qa’ida terrorists, sometimes using remotely piloted aircraft, often referred to publicly as drones.”[4]

While the use of unmanned aircraft in warfare goes back to the early 20th Century[5], the distinctive image of the drone has come to characterise the ambiguous geopolitics of The Global War on Terror. Their hubristic names—Reapers, Predators — evoke visions of carnivorous animals carefully and selectively stalking their prey. With their stealth and capacity to observe targets for hours on end before striking, the drone selectively adopts the tactics of the insurgency: it is an emergent weapon directed onto an emergent threat. Drones, like their intended targets, are not necessarily contained by borderlines, or to territories on which the US has declared war. They are in a suspended state of exception, and are decried both as being outright illegal by experts in international law, and simultaneously, as Brennan contests, strictly adherent to the doctrine of Just War.

In Brennan’s Wilson Centre speech, he draws on medical analogies to justify the “wisdom” of drone warfare, emphasising its “surgical precision—the ability, with laser-like focus, to eliminate the cancerous tumor called an al-Qa’ida terrorist while limiting damage to the tissue around it—that makes this counterterrorism tool so essential.”[6] But are drones as precise as Brennan’s rhetoric implies? Drones are often said to be heard, and not seen—their whirring noise inspiring local derisive colloquialisms[7]. But it is especially in the drone crash that the drone can be seen, and what’s more, subjected to inspection. It alerts us to a vital consideration: the failure of so-called precision military technology.

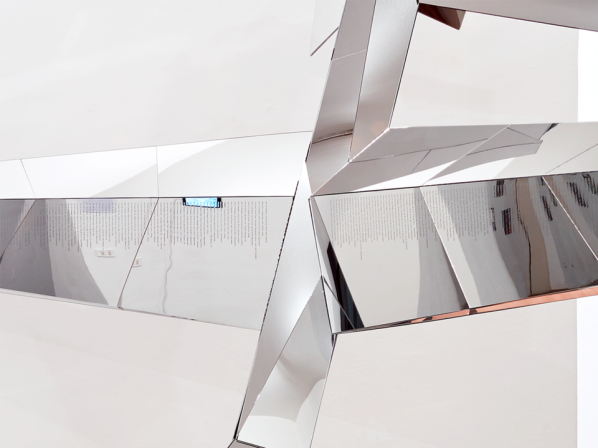

In IOCOSE‘s Drone Memorial, our attention is drawn to the fact that these complex systems are precarious, that the drone is indeed a fallible technology. The memorial, a sculpture of a fallen Predator drone driven into a copper plinth like a blade, subverts the surgical metaphor proposed by John O. Brennan. The drone’s mirrored surfaces create a fractured, tesselated reflection of its surroundings, its form almost vanishing in a specular camouflage. Inscribed on its wings are the memorial’s “fallen comrades”, the hundreds of other drones that have crashed, listed by location and date. This list can only be considered a selection, however, such is the secrecy around the use of drones in the War on Terror. As such, it should also be considered a monument to the journalists who manage to report on the discrete events of drone warfare in incredibly challenging circumstances.

A GPS beacon embedded in Drone Memorial broadcasts the location of the sculpture on the project website, hinting to us that this seemingly trivial technology in our smartphones has more nefarious uses. Global Positioning Systems have their roots in Cold War ballistics research, specifically in a program by DARPA codenamed TRANSIT, developed to direct the US Navy submarine missiles to “within tens of meters of a target”[8]. Today, GPS is one of many components in the assemblage of technologies used in the drone, and a key enabler of its apparent “precision”. Nevertheless, GPS can of course fail—it can be “jammed” inadvertently, or indeed tactically manipulated by malicious third parties. When the satellite link is lost with a drone, the aircraft goes into a holding pattern, flying autonomously until control is regained. In the Washington Post‘s story “When Drones Fall From the Sky”, they note that in order to keep its weight at a minimum there is little redundancy built into the drone’s on-board systems. Without backup power supplies, transponders and GPS links fail, and in several cases “drones simply disappeared and were never found.”[9]

IOCOSE’s positioning of the memorial as existing in a hypothetical, post-war scenario poses some interesting questions, but this temporal dissociation is perhaps unnecessary, for this is an issue very much of the present. It is certainly a topic more than worthy of critical investigation—the spectacle and the political consequences of failure have largely been left out of typical artistic engagement with drone warfare. In their press release accompanying the work[10], the artists suggest that the sculpture has an absurd quality. To me, it is not absurd as much as it works as an apt memorial to the violence of failure. In reading the long list of drone crash locations, the viewer might begin to probe the question of what information should be open to public scrutiny. IOCOSE pose the following question to us: “Does a drone crash count as a technological failure, or as a casualty?” This question would appear to have a clear answer: we must see the drone crash as a technological failure, so as not to make a false equivalence with the real casualties of drone warfare—the civilians who are subjected to it, the very same people who might also counter Brennan’s claims that the drone is a surgical, precise weapon of war.

Drone Memorial is the third work in a series titled In Times of Peace. This most recent work is the most astute in challenging the legally and ethically disruptive paradigm of drone warfare: it pierces the reflective rhetoric of US defense officials, and directs our attention to the high-stakes violence of its technological failure. The memorial, of course, ordinarily comes after the historical moment. This ‘moment’ is very much still unfolding 15 years later, and as the Trump administration takes form, it seems that the way in which drones will be deployed in the future is an ‘unknown unknown’. Thus, Drone Memorial is a temporal snapshot, an aesthetic pause on an ongoing, mutable war that seems to operate on a parallel continuum, only occasionally visible. More drones will continue to fail, as the drone war inevitably continues. These failures present a moment for critical analysis, a flash of visibility that should be seized upon.