These days, drones are everywhere: conducting military strikes across Pakistan, Yemen, Somalia and Afghanistan; as the underpinning technology for public health infrastructure; for sale to delighted kids in Hamleys toyshop; or as D.I.Y kits and readymades from the Internet. Amazon has proposed to sell fleets of drones, offering super-fast deliveries to its customers.[1] In Haiti, Bhutan, Papua New Guinea and the Philippines, drones have helped rescue natural disaster victims – and transport medical samples and supplies[2] and the Aerial Robotics Laboratory at Imperial College London is developing networks of drones to deliver blood supplies to rural health clinics in Africa[3]. The new ubiquity of drones in these contexts means that we need to think carefully about the personal and political impacts of the emerging drone culture?

Drones: Eyes From A Distance will be the first gathering in Berlin- April 17-18 2015 – of the Disruption Network Lab. This two day symposium presents keynote presentations, panels, round tables, and a film screening held in cooperation with Kunstraum Kreuzberg /Bethanien, with the support of the Free Chelsea Manning Initiative. The event is being held at the Sudio 1 of Kunstquartier Bethanien. And this conference would not be happening if it wasn’t for the tireless dedication of Tatiana Bazzichelli, founder of the Disruption Lab.

As part of Furtherfield’s partnership with the Disruption Network Lab I will chair a panel with Tonje Hessen Schei (filmmaker, NO), Jack Serle (investigative journalist, UK), Dave Young (artist, musician and researcher, IE).This interview with Dave Young is the first of three, in the lead up to the Berlin event.

Dave Young is an artist and researcher based in Edinburgh. His practice follows critical research into digital culture, manifested through workshops, website development, and talks on subjects varying from cybernetics and the Cold War history of network technologies, to issues around copyright and open source/free culture. He is founder of Localhost, a forum for discussing, dismantling and disrupting network technologies. Past events have focused on Google’s entry into media art curation, and the role of analogue radio as a potential commons in the digital age.

Marc Garrett: Hello Dave, I first met you in London when you hosted the Movable Borders: The Reposition Matrix Workshop’s at Furtherfield Gallery in 2013 as part of a larger exhibition called Movable Borders: Here Come the Drones! I remember it well, because the exhibition and your workshops were very well attended and a cross section of the local community came along and got involved. Could you tell us what your workshops consisted of and why you did them?

Dave Young: The workshop series came out of my own research into the history of cybernetics and networked military technologies while I was studying at the Piet Zwart Institute in Rotterdam. The US Military’s use of drones in the War on Terror had been officially acknowledged by the Obama administration by this time, and I was becoming increasingly curious about the apparent division of labour and accountability involved in the so-called ‘kill chain’ – that is, the structure and protocols that lead from identification of a potential target to a ‘kinetic strike’. As the use of drones was still largely a covert effort, there was much speculation in the media about where and how they were being used, so the idea of exploring these issues in a workshop format seemed to be a good way to create a public space for considered discussion and debate.

The workshops had quite an open format, with outcomes largely dependent on the interests and knowledge of the participants. The central task of each workshop was to collectively research a particular aspect of the military use of drones, and through the process of charting this research on a world map, we could then begin to discuss various geopolitical patterns and trends as they emerged. Rooting the workshop in this act of collaborative mapping provided an interface for discussing drones in specific terms, and helped situate their use within the reality of an incredibly complex historical and geopolitical narrative. To me, this provided a useful alternative to the mainstream media reporting styles that seemed to often rely on the same metaphors and controversies in the absence of real information coming through official sources.

MG: What are the specific concerns you have regarding the development of drones and how do you think these conditions can be changed for the better?

DY: This is a question I was more sure of before I started the workshop series – I feel the more I’ve gained an understanding of the way they’re used, the less sure I am of what needs to change. I see the drone as a symbol for the way conflict is understood post 9-11. It is part of the language, aesthetics, and transnational politics of the War on Terror. What is most concerning to me is the idea that the drone allows a state to fight a war while apparently sidestepping the otherwise necessary apparatuses of legality and oversight. As a covert weapon, it can be implemented in exceptional, extra-judicial ways that have not been legislated for as yet. The “targeted strike” and “signature strike”, while distinct from each other in protocol and circumstance, are particularly problematic – the former amounts to what many journalists describe as an assassination, although this word is rejected by the US government.

The CIA Torture Report released at the end of last year was an important acknowledgement of institutional subversions of legal and moral codes. I’d expect that a similar report into the use and effects of military drones would create space for an informed public debate about how they might be used in the future.

MG: Regarding you own relation and interests around drone and military culture, what are your plans in the near future?

DY: The outcomes of The Reposition Matrix have led me to approach this issue in a different way, looking for alternative ways of instigating conversations around this difficult subject. I’m still quite occupied with issues around the collection and presentation of data – during the workshops we covered a lot of diverse subjects, but always situating research outcomes on the surface of a world map. The question for me right now is what information is important to work with, and how can it be usefully represented? I’m looking at alternative methods of “mapping”, perhaps based in mapping technologies/software but using them in more disruptive non-geographic ways. I’ve been quite inspired by Metahaven’s ‘Sunshine Unfinished’ and the recently published book ‘Cartographies of the Absolute’ – both works have brought me back to some possibilities that went unexplored in the initial run of workshops back in 2013.

MG: What other projects are you involved in?

DY: Aside from this research, I’m currently collaborating on a project titled “Cursor” with Jake Watts and Kirsty Hendry as part of New Media Scotland’s Alt-W fund. We’re investigating current trends in fitness tracking technologies, and attempting to uncover and critique the way such intimate personal data is produced, distributed, and commodified. You can follow our research as it evolves on http://cursorware.me

I’m also running a space here in Edinburgh called Localhost, with the aim of stimulating discussions around the political aspects of digital art/culture. I run regular workshops and more occasionally special events, but I’m also very happy to provide a platform for others who wish to share their thoughts & skills on related subjects. Check http://l-o-c-a-l-h-o-s-t.com/ for more information and how to get involved.

Thank you very much 🙂

Featured image: Screen capture of Joseph DeLappe’s intervention in America’s Army

The Fresno Art Museum, in collaboration with the Fresno State Center for Creativity and the Arts, is exhibiting “Social Tactics,” a mini-retrospective of the work of Joseph DeLappe, a new media artist and director of the Digital Media Program at the University of Nevada, Reno. The exhibit has been running alongside the construction of a to-scale sculptural reproduction of an MQ1 Predator Drone on the campus of Fresno State, coordinated by DeLappe and executed by students and volunteers. I had the opportunity to interview DeLappe about his work, and the way it connects to militarism, memorialization, and embodiment. His work has been an ongoing critique of games that look like war, and warfare that looks like gaming – insisting that, within the hall of mirrors that forms “simulation culture,” reality still must be accounted for, and attended to.

The earliest work in the show is a series of riffs on the computer mouse. The “Mouse Mandala” (2006) splits the difference between a trash heap and an object of meditation – a small sargasso of computer mice is ringed by a circle of yet more mice. The outer radius, tethered to the central mass by extended mouse cords, makes the whole sculpture resemble a dingy grey sun – one that has been pawed by innumerable, invisible fingers. His “Artist’s Mice,” first begun in 1998, are a series of mice that have drawing implements attached to them, so that the mice can draw while being utilized for their normal activities. The drawing attachments resemble braces, as though the mice are being rehabilitated from an injury – the drawings produced by them are beautiful abstractions, circular or square scribblings that give the illusion that, while working or gaming or goofing off, we could also be making art – skimmed off the surface of our interface with our machines.

All these mice, removed from the context of their guiding hands, inevitably – if ambiguously – echo with a pair of outsized sculptural hands, titled “Taliban Hands” (2011). Modeled from white plastic polygons, the left hand in particular looks as if it could be cradling an invisible, equally outsized mouse. The right hand has its pointer finger extended, as if it were about to press a button. The fact that the hands are upturned short-circuits those prosaic possibilities of gesture, turning them into gestures of supplication. The hands were constructed from 3D data extracted from the model of a Taliban fighter in the game “Medal of Honor,” and once you learn that, it’s easy to imagine the right hand gripping a gun, the extended finger wrapped around the trigger. The disembodied nature of the hands is discomfortable – it feels like a dismemberment, a pair of hacked war trophies offered up for display.

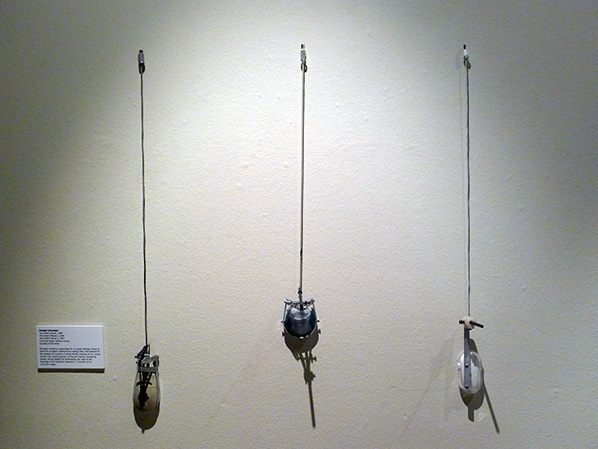

DeLappe also used polygon modeling for a small replica of a US military Drone that hangs in the gallery, which served as a prototype for the life-size drone constructed as a memorial on the grounds of Fresno State. Where the “Taliban Hands” and drone prototype are white and pristine, the Drone Memorial was designed to be inscribed upon. In a public ceremony, volunteers wrote the names of 334 civilian casualties of drones on the faceted surface of the sculpture.

DeLappe’s years-long project “dead-in-iraq” (2006-2011) is represented by a machinima video and a large-scale digital print modeled after his fallen avatar in the US Army recruitment game America’s Army. Over the course of the American war with Iraq, DeLappe entered the multiplayer first person shooter game, and at the start of each mission threw down his weapon and began typing in the names of US military personnel who had been killed in Iraq. His avatar was invariably shot, either by the opposing team or by members of his own team. In the latter case, it’s as though his killers are trying to gun down an itch of conscience – or the nuisance of reality itself. In the machinima of this intervention, when Delappe positions his camera above his virtual corpse, there is sometimes a very profound effect of quietude. The body occasionally twitches, in a gruesome effluvium of game physics, or puffs of smoke are kicked up by stray bullets – but those filigrees of activity only heighten the feeling that the game has moved on. It brings to mind bodies left on real battlefields, unattended to, abandoned to the weather and the birds and the insects while the important business of fighting continues.

“Project 929: Mapping the Solar” (2013) echoes the circularity of the Mouse Mandala. For the project, DeLappe rode a bicycle 460 miles in a circuit around Nellis Air Force Base in Southern Nevada. The bicycle was outfitted with an apparatus that held a series of pieces of chalk to the road – DeLappe was both marking a chalk outline around the base, and mapping out the dimensions of a solar farm that could power the entire United States, based on a size estimate from the Union of Concerned Scientists. The project is shown through a series of photographs, a video, and the modified bike itself, with a circle of chalk stubs positioned under the frame. In some ways, the piece expands the logic of the “Artist’s Mice” to a different scale. Instead of the hand being the driving force, the whole body is the recorded object, and rather than being confined to the top of a desk, the drawing itself is allowed to range across hundreds of miles. In this case, the drawing is the opposite of accidental – it’s utopian.

Not represented in the show – but a point of discussion in our interview – was the “Salt Satyagraha Online” (2008), a 26-day durational performance which used a customized treadmill to control the movement of a Second Life avatar modeled after Mahatma Gandhi. On the treadmill, installed at Eyebeam Art and Technology in New York, DeLappe walked the 240 miles Gandhi marched in protest of a British Salt tax – driving his avatar, step by step, across the territory of Second Life. That project was yet another of DeLappe’s exploratory reconfigurations of the relationship between protest, performance, and physicality.

Chris Lanier: With the mouse-derived work, from the “Mouse Mandala” to “The Artist’s Mouse” and the drawings that are made as you’re playing a game – what was it like putting those things together at this time, when it’s possible to imagine the disappearance of the mouse? Right now there is eye-controlled software , and even thought-controlled software…

Joseph DeLappe: Part of my thought process when doing the mouse pieces was doing a sort of reverse engineering, and trying to figure out what that thing is, because it really is a useless little object otherwise. It’s not a hammer, it’s not a screwdriver, it doesn’t have a function beyond plugging into a computer to allow you to move around this detached marker on a screen. There’s already something separate happening, and so attaching a pencil to it was a way of perhaps returning it to its roots. It’s sort of a drawing device, a pointer, all these things that a pencil might be, but I was intrigued by the possibilities of extracting some kind of meaning out of it.

CL: It’s funny because it’s an extension from the computer to the human, like an organ that extends itself to us, and I wonder what you think of that interface becoming even more disembodied. If the hand is taken out of that circuit, what do you think that says about our relationship to the screen?

JD: I think it will change it. I can really only speak from my experience, not having played the wii, or things like that. I messed around with the kinect a little bit. When you’re putting the body into works like what I did in the Gandhi project (which is something that’s not in the exhibition) – I placed myself on a treadmill to actually interact with Gandhi, walking him through Second Life. My body became the game controller in a kind of way, the mouse – or however you want to refer to it. I didn’t realize it at first but there was an intrinsic alteration of my relationship to the experience going on, on the screen. I wonder if that deterioration of that awkward physical thing you have to do with the mouse or track ball, if that’s going to bring us closer to our machines. As it becomes gestural and everyday, I suspect it will become more naturalistic.

CL: Listening to you talk about the Gandhi project, it seemed to bring you more directly and somatically into that virtual world.

JD: Which was very unexpected. I went into that project from a conceptual durational performance ideation – this would be an examination of “performance,” in quotes. Performance and protest. It was done at Eyebeam in New York, and I was thinking about the many durational performances that had taken place in New York, from Tehching Hsieh, to Linda Montano, to Joseph Beuys. I had done performance works online for almost a decade prior to that piece, but that action that the body involves, that was just transformative. It was amazing and intriguing and kind of disconcerting in a way, because I found myself completely drawn into that experience, and connected to my avatar in a way that I never had previously. I was walking in Second Life, which you’re really not supposed to do – you’re supposed to teleport – so I was navigating over mountains and in places people don’t generally walk. And Gandhi would fall off a mountain-side into the next region, and I’d find myself almost falling off the treadmill. Or, after finishing the performance for the day, walking to the subway and thinking I could click on someone to get information. It became this mixed reality in my head.

CL: Embodiment seems to be a crucial part of your practice. With “Taliban Hands,” you extracted hands from Medal of Honor, and brought them into physical space. In the “dead-in-iraq” project you brought the names of the dead soldiers into the game space of America’s Army. It seems that bringing bodies into that space, or extracting bodies out of that virtual world, is important to you.

JD: Well, each of those pieces had different but connected intents. With the America’s Army project, “dead-in-iraq,” the intent was to embody the reality of the war, to bring it to this virtual space. So when you’re dying and or you’re killing in that virtual space, and you see these names go across the screen, you realize that this is an actual person that died in that conflict. That might change another player’s thought process about what they’re doing, and about that visualization – when you get shot you end up hovering over your fallen avatar. So there is this attempt to change how one considers that experience.

CL: It’s interesting, with the self-portrait as dead soldier – the way of marking yourself as dead is to show the body within the game. Moving you from a first-person space, a first-person-shooter space, into a third-person space. The body becomes a marker of death.

JD: That is certainly a problematic aspect of that game. I think the vast majority of the people playing the game – certainly there are some veterans and active military – but there are more people who aren’t in that situation. So there is this kind of temporary inhabiting of the US military. Bringing this out into real space is an attempt to drive home the connection of that fantasy pretend space to a very real space. It’s like bringing it to a sort of mid-ground. The America’s Army game is in fact official US military virtual space. I mean they own it. It is federal space – it’s part of the system of hundreds of bases around the world.

With the Taliban hands, it’s a similar attempt, but with a different thought process. With the America’s Army game, one of the most devilish things they did with that game is that they’ve created a system where everybody gets to be a good guy. There are two teams, and you see your team of 2 to 12 cohorts playing against 2 to 12 other cohorts. You always see yourself as Americans. They always see themselves as Americans, but you see each other as terrorist enemies. So there’s this digital switching, where they see your avatar as a Middle Eastern terrorist and vice versa.

CL: The strange thing that happens is that you’re inhabiting two bodies.

JD: Yeah, at the same time, exactly. But in the Medal of Honor game it’s not like that. That was a controversial game when it came out in 2010 because you could play as a Taliban killing American soldiers. It was the only game that was actually banned from military bases. They ended up changing it before they released it – they weren’t called “Taliban,” they were called OP 4, which stands for opposition forces. But you’re still Taliban. So anytime that game is being played as an online match, 50% of the players are being American and 50% are being Taliban.

I found that really curious. I started extracting these maps from that particular game, and then diving into this incredible morass of 3-D data. I would have to dig through all of this wireframe stuff to find these objects, and I found the Taliban and started deleting everything else, and landed at one point with the hands. It was just so intriguing – these hands were gorgeous. When they became disembodied from their source and I started visualizing them in the 3-D software, they took on a kind of Da Vinci-esque quality – like the hand of God or something.

CL: There is a gestural quality to it.

JD: Yeah, exactly.

CL: I’m curious if this work has brought you more into contact with the idea of simulation. Simulation can be useful, obviously – it allows you to think through a situation before it’s actually encountered. But then it can actually introduce errors into the actual [situation], because the simulation doesn’t correspond absolutely to reality.

JD: I don’t know if this connects to your question at all, but if you die in America’s Army – this is standard in most shooter games – they have something called the ragdoll effect. It’s a simulation of your body going limp. It’s meant to give a naturalistic [simulation of] you collapsing, and you’re dead. But the effect is actually quite different – there are points where your avatar, in that space – it can be almost comical, like you’re going to do a somersault. And every time you actually die, your body – because of that ragdoll effect – you watch the video and the avatars do this kind of shaking thing, that’s part of this ragdoll effect. When I first saw it I thought it was this macabre death spasm, but it’s just part of the simulation. It’s not meaningful in the context of the game, but it becomes meaningful in the work that I did and in the recording of it.

CL: It’s funny that a simulation can have these unintentional, almost poetic, effects – if you are attuned to it.

JD: And that’s a good metaphor for the whole project, right? It’s taking this simulated wargame – this recruiting tool – and re-branding it, remaking it. It’s a way to say: “No, let’s see if we can make this game be about this, not about that.” I appropriated the space – I took it over in a simple way, and I think it was quite effective.

CL: You frame yourself as an activist as well as an artist.

JD: Yeah, and sometimes uncomfortably. I drift in and out of that. There’s a difference between being an artist and activist. And right now I’m feeling rather reticent [about the “activist” label] – but I’m an artist at base. It’s a little bit more symbolic I guess…

CL: Making a political act in a virtual space – is that inherently symbolic?

JD: That’s a really interesting question because in the progression of my work, I think my work has slowly emerged towards existing in a real space – with the bike-riding around the Air Force base, and now building a life-sized predator drone down in Fresno.

As an artist you do deal with a kind of symbolic reality – metaphor and symbolism, and things that communicate ideas through form. As an activist it seems there would always be a goal of actually fostering change, making change happen in the world. Whether activism is effective at doing that – that’s a really big question too, right? I’m not sure sure if that’s the case these days. That’s one of the reasons I was interested in going into the America’s Army project. It was seeing the – I wouldn’t say the complete failure – but the invisibility of traditional forms of protest. You had the world’s largest worldwide gatherings of protest, a year before we started that war, which was totally under-reported…

CL: And under-counted.

JD: Right. And I’m not saying that I never want you to go protest in these places, but you do have to push that envelope into places where people would not expect it, to actually reach people. And that was a surprise actually, that that piece resonated so powerfully with others – and became a viral thing that, by accident, was disseminated to a huge audience. That was good. But I’m not sure how I feel about it as a kind of permanent venue for trying to do that kind of thing.

With the “dead-in-iraq” project, there were some people who were criticizing it, saying, “Well, you’re just sitting there at your keyboard.” It’s like: “Yeah? Right. I know that – that’s part of the point. Everybody playing that game is sitting at their keyboard.”

CL: And the people who are manning drones are sitting at their keyboards.

JD: Precisely, and that’s exactly one of the reasons I’m so interested in drones. Speaking of embodiment, the drones –it’s like a perfect synthesis of computer gaming culture, and our militarism, and our love for the latest possibilities of technology. It’s like somebody bashed those things together and out came this perfect system for blowing shit up on the other side of the planet – sitting in your comfortable gamer’s chair.

CL: The way you’re activating the Drone Memorial as an extension of your art activism – I’m wondering if part of the appeal is doing it within an educational institution, where you’re enlisting students to help you out, so it actually becomes part of an educative process. How much do they know about the drone policy?

JD: What’s interesting with that project is that they brought up these different groups – art students, design students, and there has been a group of activists from Fresno called Peace Fresno who’ve come out to work. There have been some TV interviews, and there’s a journalism class – they’re taking turns, every day there’s a different crew and they’re documenting the process and interviewing the people that are involved. And it’s been interesting talking to some students because there have been a number of students that are like: “What, drones? We can blow stuff up in Pakistan, from sitting in Las Vegas at Creech Air Force Base?” They don’t know about it, so there is a kind of basic informational aspect of the project.

But what I’m finding most interesting is that the students and volunteers – and myself – at this stage of the work we’re so absorbed in the embodiment, if you will, of the physical sculpture. It’s a building process and there’s a kind of pleasure in that. There’s the hands-on aspect of building, and seeing this form come into being. What I’m waiting for is that realization when we get the whole thing together, and it has this 48 foot wing span and 27 foot fuselage, sitting on the ground at the campus – and then we write the names [of the civilian casualties on the sculpture] – we have 334 names in English and Urdu.

I think that’s going to have a powerful impact, that’s going to completely flip the equation. Not just to give them a sense of their making something as a community build – but that we own these drones – we are this policy. These victims that are on the drone are connected to us, right? There’s a direct lineage from that pilot sitting in Creech Air Force Base, from the missile that rained down on that village and killed a 12-year-old girl, to you and me. It may be tentative, but it’s our government – it’s us.

Conclusion.

The interview was conducted several days before the completion of the Drone Memorial. After the sculpture was assembled and installed, there was a public ceremony at the site. Afterward, I asked Joseph if the effect of the ceremony was in fact what he envisioned, and he sent me the following reply via email:

We finished the drone just as the ceremony was scheduled to commence. There was a crowd of about 75 people – I made some brief comments thanking the volunteers and the CCA. The actual ceremony was being coordinated by a wonderful group, “Peace Fresno”, who coordinated the creation of individual, hand written index cards, each with the name, date of death and age (if available), of each of the 334 Pakistani drone victims. These were read aloud by individuals from Peace Fresno of Pakistani or Indian descent to ensure that the names were correctly pronounced. Those gathered for the event stood in line to take possession of a name after it was read aloud – walking towards the drone where they were given a pen. Each name was written with the associate dated of death and age of the victim when available. Several volunteers followed this process by filling in the names translated into Urdu.

I personally completed the process of standing in line, taking a pen and writing names on the drone 7-10 times, I lost count. The most memorable was that of an 8 year old girl – I don’t recall her name but after writing on the drone the realization of the death of a child was quite overwhelming. Others had similar experiences – there were several walking away from the drone after writing their name who were in tears. This cycle of writing, standing in line and continuing the process went on for perhaps 45 minutes until all 334 names were written upon the drone. All the while there were passersby stopping, asking what we were doing, some joined us. I recall a father on a bicycle have a discussion with his young son about drones, “are you ok with being surveilled 24/7?”, that kind of thing.

In my exhaustion after working 2 weeks followed by an additional weekend of 11 hour work days, the experience was moving and quite overwhelming. There was indeed a palpable realization of the nature of the project. The camaraderie established among the workers and volunteers evolved into a collaborative process of memorialization.

“Social Tactics” runs through April 27, and the Drone Memorial will be on display through May 31.

Joseph DeLappe’s website: http://www.delappe.net

A previous furtherfield interview on another drone-related project by DeLappe:

The 1,000 Drones Project, by Marc Garrett – 05/02/2014, furtherfield.org

http://furtherfield.org/features/interviews/1000-drones-project-interview-joseph-delappe

News story on US Military objections to ‘Medal of Honor’:

Sales of new ‘Medal of Honor’ video game banned on military bases, by Anne Flaherty – 09/09/2010, Washington Post

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2010/09/08/AR2010090807219.html

News story and video on the Drone Memorial:

Drone project at Fresno State a call for ‘contemplation’ (video), by Carmen George – 03/26/2014, The Fresno Bee

http://www.fresnobee.com/2014/03/26/3845089/drone-project-at-fresno-state.html

Fresno College Newspaper story on the Drone Memorial:

Drone sculpture construction begins, by Collegian Staff – 03/18/2014, The Collegian at Fresno State

Drone sculpture construction begins

Essay on the visualization of the “Enemy” in military games, with a focus on “America’s Army”:

The Unreal Enemy of America’s Army, by Robertson Allen – 01/2011, Games and Culture 6(1):38–60

http://www.academia.edu/231295/The_Unreal_Enemy_of_Americas_Army

Featured image: Cardboard Soldier, 2009 exhibition T-Space Gallery Beijing. Joseph DeLappe.

Joseph DeLappe’s art projects have received much interest ranging from the art world, New York Times, Wired magazine, and publications such as Joystick Soldiers The Politics of Play in Military Video Games, the first anthology to examine the reciprocal relationship between militarism and video games. DeLappe is considered a pioneer of online gaming performance art. His art examines the conditions and processes of cultural information to provoke and critique the state of military influences on everyday culture and people’s lives.

DeLappe’s work includes the controversial game based, performance and intervention, Dead in Iraq 2006-2011. This involved him frequently visiting the US Army’s online recruitment game and propaganda tool America’s Army. Using the login name dead-in-iraq, he methodically typed in all of the names of U.S. service personnel killed in Iraq, co-opting the Army’s own technology challenging the official figures as a reminder to its players of the real consequences of war. He also directs the iraqimemorial.org project, an “ongoing web based exhibition and open call for proposed memorials to the many thousand of civilian casualties from the war in Iraq.”

Joseph DeLappe, “dead…whats your point?” dead-in-iraq screenshot 2006-2011.

“The players ask DeLappe to stop what he’s doing, but when he continues they shoot him or simply kick him out of the game. You can see the strong reactions from the other players as a proof that DeLappe’s performance are successful. He succeeds to break the game illusion, in the same way as Brecht “Verfremdungseffekt” breaks the illusion in drama.” [1] (Jansson)

Much of DeLappe’s work is known for challenging his own nation’s involvement with war. However, if we look at The Salt Satyagraha Online: Gandhi’s March to Dandi in Second Life 2008, his work reflects a wider context introducing his concerns on the human condition. Over the course of 26 days, from March 12 – April 6, 2008, using a treadmill customized for cyberspace, DeLappe reenacted Mahatma Gandhi’s famous 1930 Salt March. “The original 240-mile walk was made in protest of the British salt tax; my update of this seminal protest march took place at Eyebeam Art and Technology, NYC and in Second Life, the Internet-based virtual world.” [2]

On hearing about DeLappe’s The 1,000 Drones Project – A Participatory Memorial, I was immediately intrigued. I wanted to find out more and discuss his approach as well as how he intends to bring to light the lives lost by these unmanned Arial predators as an art project, and what this would look like.

Marc Garrett: Could you tell us why you felt it was necessary to do this project even though there is already much media attention out there relating to the use of drones in domestic, military and commercial culture?

Joseph DeLappe: There has indeed been much media attention surrounding the use of militarized drones as a part of US foreign policy. Our drone policies have received much attention yet, as with the coverage of civilian casualties from the Iraq war, the actual human costs of our drone strikes remains rather illusive. Through the work I am doing regarding drones that specifically focuses on memorializing civilian deaths I hope to actualize the estimates of civilian deaths and to call into question the moral issues surrounding such remote killings. You might say that drones have struck a nerve with me. There is something different about drones. They seem to perfectly combine aspects of our worst fantasies of digital technologies, interactivity, computer gaming and war. One might consider them a bit of a “gateway” weapon (the drug reference is of course intentional here). I suspect we have indeed opened a Pandora’s box leading to the further utilization of remote and robotized weaponry that will make our current drone usage seem quaint.

The above is “An ongoing series of image interventions downloading images of UAV’s (unmanned arial vehicles) in use by the United States Military, including: General Atomics MQ1-Predator Drone, MQ9 Reaper Drones and Global Hawk Drones from the top results of Google image searches. Each image is slightly adjusted to include the marking “COWARDLY” upon it’s fuselage. The saved images are uploaded to my website with basic titling information “Predator Drone”, “Reaper Drone”, “Global Hawk Drone” – with the intention of having these images begin to appear in searches for information and images on drones occurs online. The works are intended as a subtle intervention into the media stream of US military power.” DeLappe

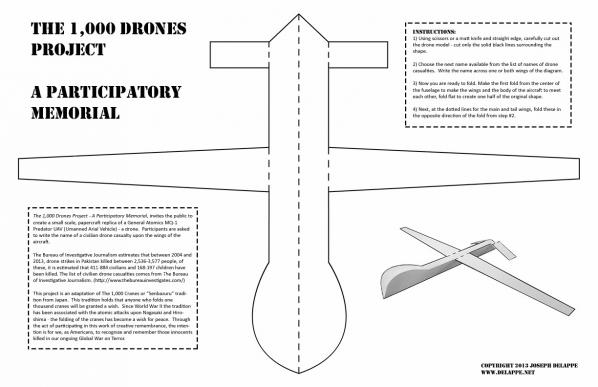

I am working on several drone projects at the moment, including The “1,000 Drones Project – A Participatory Memorial”, and seek to draw attention to and creatively memorialize those innocents killed by drones. It invites the public to create a small scale, papercraft replica of a General Atomics MQ-1 Predator UAV (Unmanned Arial Vehicle) – a drone. Participants are asked to write the name of a civilian drone casualty upon the wings of the aircraft.

This project is an adaptation of The 1,000 Cranes or “Senbazuru” tradition from Japan. This tradition holds that anyone who folds one thousand cranes will be granted a wish. Since World War II the tradition has been associated with the atomic attacks upon Nagasaki and Hiroshima – the folding of the cranes has become a wish for peace. [3]

MG: You are inviting participants to be a part of the project. In what capacity will they be taking part?

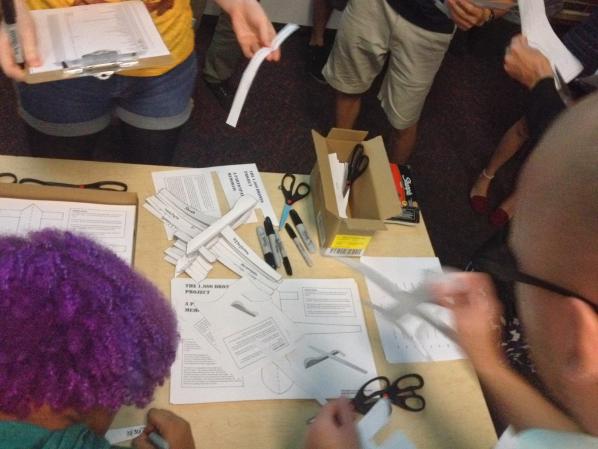

JD: The 1,000 Drones Project has been commissioned by the FSU Art Museum of the exhibition “Making Now – Art in Exchange”. The FSU Department for Art has for the past few months conducted a series of workshop events where the public is invited to make a small, paper drone from a provided template. The form is made directly from MQ1 Predator Drone plans found online. The drone shape is cut out, there are then five dotted lines denoting where to fold the paper – the result is a simple paper facsimile of a drone. Once the drone is created, the participant is invited to write the name of a civilian drone casualty along with their age at the time of death, upon the wings of the drone. The Bureau of Investigative Journalism estimates that between 2004 and 2013, drone strikes in Pakistan killed between 2,536-3,577 people, of these, it is estimated that 411-884 civilians and 168-197 children have been killed. The list of civilian drone casualties comes from The Bureau of Investigative Journalism. We are also using a list of drone casualties from Yemen found here: http://en.alkarama.org/documents/ALK_USA-Yemen_Drones_SRCTwHR_4June2013_Final_EN.pdf

At present we have a total of 464 persons identified as civilian drone casualties from Pakistan and Afghanistan. To complete the 1,000 drones, the remainder will be marked “unknown”.

The paper drones are to be strung together in groups of 18 per string, 55 strands will be hung in the center of the gallery to create an installation that will be triangular in shape. The making of the drones will continue with the opening of the exhibition in February until 1,000 are complete and installed.

MG: What will others learn or gain from this participation?

JD: This is difficult to pin down. My intention is that through the act of making a drone, followed by writing a name or “unknown” upon their creation that individual participants will in some small way actualize the loss of individual lives due to our drone attacks. The intent is to perhaps for some brief moment make real these deaths taking place in our name on the other side of the globe. The actions are decidedly low-tech as well – there is something important in this – the deaths become physical, perhaps drawn from the digital media stream, the digital process of the killings to a direct, physical act of making and remembering. I am very interested as well in the overall effect of the piece – to see 1,000 white paper drones hanging in space as a memorial will likely have a powerful impact. Numbers of civilians killed as reported through our media are all too often numbing and abstract – this piece will hopefully make real this abstract process of digitally remote killings.

MG: What is the lineage of this project?

JD: I’ve been working intensively over the past decade to creatively shed light on civilian and military casualties as a result of our ongoing “war on terror”. This includes “dead-in-iraq”, my intervention as a memorial and protest taking place within the America’s Army computer game and iraqimemorial.org, a crowd sourced project launched in 2007 inviting anyone to post concepts, imagined memorials to the many thousands of civilian casualties from the Iraq conflict.

Looking at DeLappe’s breadth of work informs us how detailed and complicated the subject is, and it equally reminds us how distant we all are from any quality debate about war and drone technology and the impacts these militarised technologies have on citizen’s lives. Thankfully, on the subject of drones the Internet is supplying us with different view points that mainstream news media fails to seriously investigate. Russia Today, reported that classified documents from the CIA could not “confirm the identity of about a quarter of the people killed by drone strikes in Pakistan during a period spanning from 2010 to 2011.” [4]

Kate Rich and Natalie Jeremijenko in 1997 as part of the then, anonymous Bureau of Inverse Technology were pioneers of the first art drone ‘The BIT Plane’. This work was featured in a group show at Furtherfield’s gallery, Movable Borders: Here Come the Drones! in May 2013. [5] In an article in Mute magazine Rich wrote, “The morally disgusting asymmetry of drones relates not only to their deployment by the powerful against the weak, but also to the radical disparity of risk entailed in exposing the defenceless living to pilotless killing machines.” [6] This brings to mind how vulnerable we all are to the whims of the powerful. This feeling of fear will strike at the heart of any humanist not on the ‘right’ side of those wielding such awsome destruction without challenge, until its too late.

DeLappe’s art not only reflects the militaristic world we are living in he is directly engaged with it. His focus on his nation’s obsession with war echoes what James Hillman wrote in A Terrible Love of War, “Hypocrisy in America is not a sin but a necessity and a way of life. It makes possible armories of mass destruction side by side with the proliferation of churches, cults and charities. Hypocrisy holds the nation together so that it can preach, and practice what it does not preach.” [7] (Hillman 2004)

Many contemporary artists are working with and critiquing Bio-Technology, Nano-technology, engineering, issues on Climate Change, border controls, data-mining, surveillance, economic and political fluctuations, and the military. This is in line with the expansion of the networked society. Controversies and battles are taking place in a time of uncertainty, where the very technology and systems that have supported progress, through its worldwide channels of production and prosperity; are now the very same tools threatening the survival of our species, contributing to climate change and the emergence of the economic, global crisis, as well as a threat to our civil liberties. Art and critical thinking examining this complex and strange territory and its impacts on us and the planet are right up there in pushing forward a new kind of radical investigation as an art practice.

Joseph DeLappe’s next exhibition ‘Social Tactics’ will be from January 24 to April 27, 2014 Fresno State Center for Creativity and the Arts, in the US.