Choose Your Muse is a new series of interviews where Marc Garrett asks emerging and established artists, curators, techies, hacktivists, activists and theorists; practising across the fields of art, technology and social change, how and what has inspired them, personally, artistically and culturally.

Mike Stubbs became director of FACT (Foundation for Art and Creative Technology) media arts centre, based in Liverpool in 2007, just before Liverpool’s Capital of Culture year. The centre offers a unique programme of exhibitions, film and participant-led art projects. He views the organisation as to be cutting-edge of art and new media and one of the jewels in the crown of Liverpool’s ongoing cultural renaissance.

Stubbs has worked as an advisor to the Royal Academy of Arts, The Science Musuem, London, Site Gallery, Sheffield and NESTA (National Endowment for Science Technology and Art), ACID (Australian Centre for Interactive Arts) and the Banff Centre, Canada. He has been Production Advisor to artists such as Roddy Buchannan, Luke Jerram and Louise K Wilson.

Trained at Cardiff Art College and the Royal College of Art, Stubbs’ own internationally commissioned art-work encompasses broadcast, large scale public projections and new media installation. In 2002 he exhibited at the Tate Britain, 2004 at the Baltic, Newcastle, 2006 at the Experimental Arts Foundation, Adelaide. He has received more than a dozen major international awards including 1st prizes for Cultural Quarter, at the 2003 Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennial, Japan, WRO Festival, Poland 2005, Golden Pheonix, Monte Negro Media Art Fest 2006. In 2003 he was awarded a Banff, Fleck Fellowship.

Marc Garrett: Could you tell us who has inspired you the most in your work and why?

Mike Stubbs: Uncle Islwyn Thomas (deceased) who told a barman to bugger off in Welsh for not serving us (age 14) – It made me realise one could object.

David Nash. I was lucky to have a chance visit to his studio (chapel) when I worked in Llechwedd Slate Mine Craft shop, Blaenau Ffestiniog. He persuaded to save up for a Kawaskai Z650 in the future and not to be a paint sprayer and instead, go to art college (circa 1976…), and that being an artist was a viable alternative.

And Krzysztof Wodiczko, I saw his Cruise Missile projected on Nelsons Column in 1985 and then him swivel the projector and project a swastika onto the south african embassy in response to Margaret Thatcher donating £7 million quid to PK Botha government – big slap in the face to the anit-apartheid movement of which I was part (Greetings From the Cape of Good Hope can be found here, http://mikestubbsco.ipage.com/artworks.html)

MG: How does your work compare to those who’ve influenced you, and what do you think the reasons are for these differences?

MS: With age I’ve tempered the urge to object to too much and post election, I feel like I’m from another planet. Workwise, I’ve been priviledged and lucky to build support within the public sector for arts organisations which have maintained some edge (Hull Time Based Arts, ACMI, FACT). Recently very proud to have produced Group Therapy, Mental Distress in a Digital Age, which is both critical and a form of social activisim. I am lucky to have collaborated in developing festivals including : ROOT and the AND (Abandon Normal Devices) which have created more room to commission and present a risk taking program.

MG: Is there something you’d like to change in the art world, or in fields of art, technology and social change; if so, what would it be?

MS: That longer term agendas might accept that risk and experiment are needed and that Art IS innovation and that more people from non-art backgrounds get a chance to experience and make art.

MG: Describe a real-life situation that inspired you and then describe a current idea or art work that has inspired you?

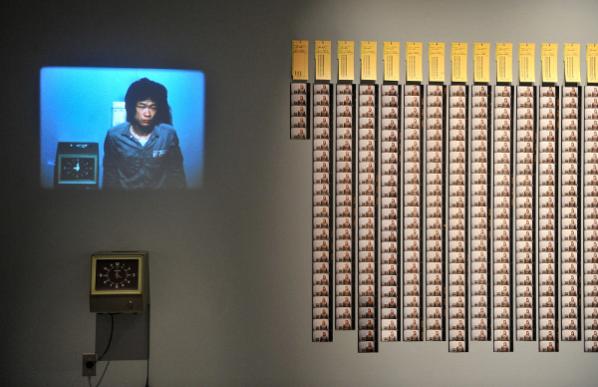

MS: Watching on TV a flood victim being rescued by helcopter and dropping her entire belongings. And Hseih Teching’s One Year Performance.

“Tehching Hsieh’s work, informed through a period spent in New York City without a visa, experiments with time. He was actively ‘wasting his time’ by setting up a stringent set of conditions within five different year-long performances. The driving force for an individual to perform such extreme actions must surely be the ultimate cipher for being emotionally, psychologically touched – and that, ultimately, is a gift. His work poses the question: as humans how can we afford not to be touched?” [1]

MG: What’s the best piece of advice you can give to anyone thinking of starting up in the fields of art, technology and social change?

MS: Do what you feel like. Dont copy others

MG: Finally, could you recommend any reading materials or exhibitions past or present that you think would be great for the readers to view, and if so why?

MS: Post-humous papers Robert Musil, they continuously speak to me at the most fundamental level and with wit. http://bit.ly/1PYIq6A

Diamond Age Neal Stephenson. Inspired the idea of democratising interactive media. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Diamond_Age

Art of Experience John Dewey, a bible of ideas to re-frame arts and culture – first citing the term ‘impulsion’ – http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Art_as_Experience

The City and the City, China Meilville. It inspired our exhibition Science Fiction, New Death at FACT. It elegantly suggests how we simultanesouly occupy the same political, social and physical spaces despite difference.

Featured: Toast McFarland

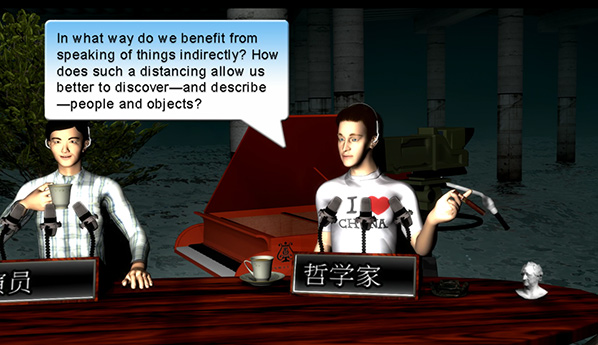

Synthetic bodies, mediated selves. What themes become relevant in a technoprogressive world – as objects proliferate, what do the inundated people talk about?

You are alone, at a computer. You talk to people but they are not around. There is no bar, no village square, no space in which you speak. There is your device and your physical presence. The social location is your body and its interface with the communicative device. What is the language for landscapes which can’t be seen, and yet which predicate subjectivity?

You express yourself. You are certain state statistics, a resume, you are a myspace profile long defunct. We require your legal name. Certain cards, from when you were born, from when you became qualified to drive, define you, make or break you. You are an ok person provided your paperwork is in order – morality is preceded by bureaucracy.

What’s the relationship between a legitimated self and that person’s body? The more modes of documentation we have the greater possibility for fictional aberration. The disparities between someone’s situated life and the records which make up their memory proliferate.

The image above by artist Toast McFarland was taken in a cartoon world. It is a selfie, a socially streamed validation of presence, but it is also a meticulous reframing of that practice. Everything is subtle, deceptively common, and yet the composition is entirely irreal. Flat colours, almost abstractly plain costuming, this is what happens when a vector world invades your computer room. It exists between personal expression and the self as actor within the surreal.

Leah Schrager‘s modelling-inspired self-portraits covered over with bright streams of paint. The model image professionalizes the act of self-representation in image form. In the profession there are industry demands – self-validation may be about confidence and friendship, where industrial success might tend towards epitomization and abstraction. Are you a good model – do you meet the sexual and aesthetic demands of the collective consumer unconscious? Schrager’s work combines a toying with such psychological implications with a background in their material underpinnings – the body in dance, the body in biological study. This combination allows for work and commentary that penetrates the relationship between the vessel you are indelibly given and the psychological relationship it develops mediated for oneself and a public.

Do you view Schrager’s images out of an interest for her or for the type of beauty she represents? Once the image is painted over, is there any interest left? Through different personas, she delivers these in a variety of web contexts, each time asking us to reconsider who we’re looking at, and who we are to look.

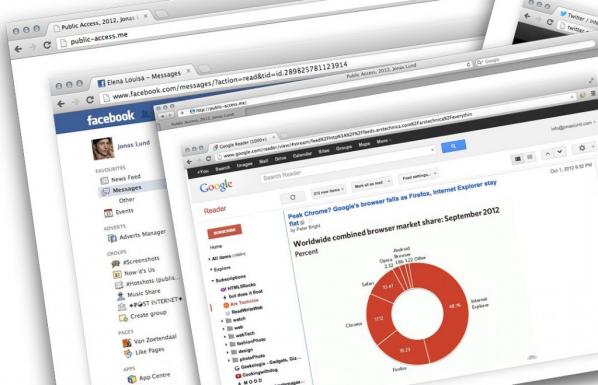

Screens, correspondents, professional speakers. We are happy to take your call. These two screenshots are taken from two videos by media artist Aoife Dunne. Both combine a juxtaposition of found broadcast footage, the enveloping commercial TV world, and her own crafted filming sound stages. They are installations, videos, and imagist combinations that take our question of the self directly to the media world. In the second, Dunne acts directly over top found footage, performing as doppelganger of the telemarketer in the projection. Her simultaneously comic, retro and coolly provocative aesthetic places her into an 80s infomercial dream world. She acts her own fiction, the selfie is the superlative thought experiment, and yet the proliferation of doubles buries her subjectivity in an imagined space of marketed image sheen. In the first work we only have a double, and Schrager’s biological world is fleshed out and externalized. This is what you really look like. Dunne’s own medicalized outfit says that this telecommunication is also a biological translation. For your image, we need your face, but for your face, we need organs and cells. Between the public and economic demands of the screen, and the material demands of your body, where are you?

Dafna Ganani‘s work, through a combination of images, code, social internet art and theoretical reflection, gives us an exemplar of how self-representation meets technical distortion. Her own performative presence proliferates in her work, yet always accompanied by animations, entire interactive worlds complicating any personal space. In this image, self-reflection is directly addressed – at first glance it mirrors what is represented but on closer inspection nothing of what that would look like quite match up. Where are the dragon head things located, where is she, before and after mirroring – the almost comical comparison is undermined by a disquieting sincerity. She appears intent on knowing where she is, however much the dragon doesn’t have her best interests in mind. And the right hand, reaching into the animation cloud on the left, nowhere to be seen on the right.

Dunne’s world of media culture screens is made specific and celebratory in Georges Jacotey‘s self-portraiture as Lana del Ray. An internet performance artist whose work explores media culture and self-image, the picture’s combination is both nearly seemless and parodically collaged. We all participate on some level in commercial culture, but we can never admit it. We might genuinely like aspects of it, we might hate aspects – but the popular bent of this culture means that as long as it is pleasing to a common consumer base it will gain a cultural existence. You know so much about iconic entertainers you never asked to know about. Jacotey takes on this conundrum, joins in on it, participates – what if instead of merely liking a celebrity, you seek to emulate and become them? Some people like del Ray’s albums, Jacotey’s the one who sang them. Capitalism asks that you buy, what if you take the role to sell? Human images make for great products, before we make the necessary transactions let’s make sure we know how to transform ourselves into them.

Good self-representation requires good media savvy. Before you think about your online identity simplify the process by becoming a celebrity. They’ve already figured out all the questions of the self in society – the right names, dress, mannerisms, the right look. Everything is acceptable, everything is inspiring, nothing is quite familiar.

Rafia Santana further draws out Jacotey’s comparison of the celebrity image and the selfie. Two different trajectories are taken up here – one is to deconstruct the fictions of the “real celebrity image”. The second is to fictionalize and play with one’s own portrayal. The result is layered, offering multiple points of entry for both observation and critique. If the digital image is just bits and bytes, what happens to ethnic history, to situated lives and experience? Putting herself repeatedly in her own work, Santana asks the basic question at hand – what, in re-representation, am I? And, with Jacotey, she probes the obverse of media celebrity existence and identification. If I like a celebrity, am I participating at all in their imagery or life? If so, in what way – what right to I have to their life, or in turn, what right do they have to be omnipresent in mine?

Subjectivity is the sentence, objects the fetish – be sure to glamour up.

Be sure to dress things up so you can recognize them well. Try not to mix up hair with noses, and composure with distortion. Each act of mediation further twists and reinvents our own images. You thought you knew where your lips were, what your skin looked like, but everything that goes through the machine comes out different, strange. It’s not a human, it’s a landscape. There’s an eye at the top, but you have no idea what it’s for. In the work of Sam Rolfes, the self is almost abstract, technical distortions take over any recognizable vestige of a human. Technique is everything, humanity nothing.

The self is painted, photographed, symbolized. It’s not a live image on the phone. Sometimes people in canvases try to get out. There are a few people here, all the same, that have nothing to do with one another. In Carla Gannis‘ selfie series, we return to a cartoon realism – but this time with a few added mirrors. Is the skull in the background also her? What is that a memento of?

Death in the image, life in its reproduction. You are now invisible, but we know more about what you look like than ever. Technological proliferation upends and eliminates traditional context but can never efface bodies and their identities. Indeed its societal saturation emphasizes these presences, their inevitability and all their embodied ties that digitize incompletely.

These practices work to situate the self, the body. Physiological maps are now more important than ever – they give us the image of the virtual. Mythology says we are in an immaterial age, that humans are obsolete and will be succeeded by machines. Reality says something far more disturbing – that our own materiality is the means of that obsolescence.

These days, drones are everywhere: conducting military strikes across Pakistan, Yemen, Somalia and Afghanistan; as the underpinning technology for public health infrastructure; for sale to delighted kids in Hamleys toyshop; or as D.I.Y kits and readymades from the Internet. Amazon has proposed to sell fleets of drones, offering super-fast deliveries to its customers.[1] In Haiti, Bhutan, Papua New Guinea and the Philippines, drones have helped rescue natural disaster victims – and transport medical samples and supplies[2] and the Aerial Robotics Laboratory at Imperial College London is developing networks of drones to deliver blood supplies to rural health clinics in Africa[3]. The new ubiquity of drones in these contexts means that we need to think carefully about the personal and political impacts of the emerging drone culture?

Drones: Eyes From A Distance will be the first gathering in Berlin- April 17-18 2015 – of the Disruption Network Lab. This two day symposium presents keynote presentations, panels, round tables, and a film screening held in cooperation with Kunstraum Kreuzberg /Bethanien, with the support of the Free Chelsea Manning Initiative. The event is being held at the Sudio 1 of Kunstquartier Bethanien. And this conference would not be happening if it wasn’t for the tireless dedication of Tatiana Bazzichelli, founder of the Disruption Lab.

As part of Furtherfield’s partnership with the Disruption Network Lab I will chair a panel with Tonje Hessen Schei (filmmaker, NO), Jack Serle (investigative journalist, UK), Dave Young (artist, musician and researcher, IE).This interview with Dave Young is the first of three, in the lead up to the Berlin event.

Dave Young is an artist and researcher based in Edinburgh. His practice follows critical research into digital culture, manifested through workshops, website development, and talks on subjects varying from cybernetics and the Cold War history of network technologies, to issues around copyright and open source/free culture. He is founder of Localhost, a forum for discussing, dismantling and disrupting network technologies. Past events have focused on Google’s entry into media art curation, and the role of analogue radio as a potential commons in the digital age.

Marc Garrett: Hello Dave, I first met you in London when you hosted the Movable Borders: The Reposition Matrix Workshop’s at Furtherfield Gallery in 2013 as part of a larger exhibition called Movable Borders: Here Come the Drones! I remember it well, because the exhibition and your workshops were very well attended and a cross section of the local community came along and got involved. Could you tell us what your workshops consisted of and why you did them?

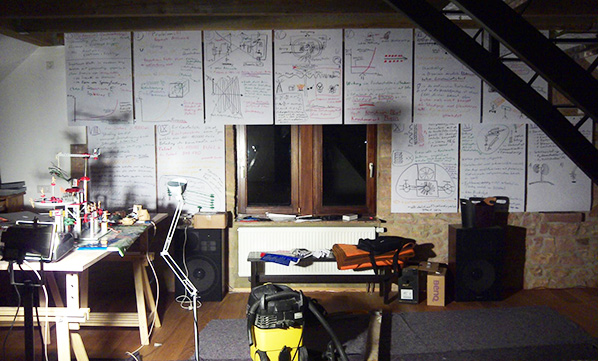

Dave Young: The workshop series came out of my own research into the history of cybernetics and networked military technologies while I was studying at the Piet Zwart Institute in Rotterdam. The US Military’s use of drones in the War on Terror had been officially acknowledged by the Obama administration by this time, and I was becoming increasingly curious about the apparent division of labour and accountability involved in the so-called ‘kill chain’ – that is, the structure and protocols that lead from identification of a potential target to a ‘kinetic strike’. As the use of drones was still largely a covert effort, there was much speculation in the media about where and how they were being used, so the idea of exploring these issues in a workshop format seemed to be a good way to create a public space for considered discussion and debate.

The workshops had quite an open format, with outcomes largely dependent on the interests and knowledge of the participants. The central task of each workshop was to collectively research a particular aspect of the military use of drones, and through the process of charting this research on a world map, we could then begin to discuss various geopolitical patterns and trends as they emerged. Rooting the workshop in this act of collaborative mapping provided an interface for discussing drones in specific terms, and helped situate their use within the reality of an incredibly complex historical and geopolitical narrative. To me, this provided a useful alternative to the mainstream media reporting styles that seemed to often rely on the same metaphors and controversies in the absence of real information coming through official sources.

MG: What are the specific concerns you have regarding the development of drones and how do you think these conditions can be changed for the better?

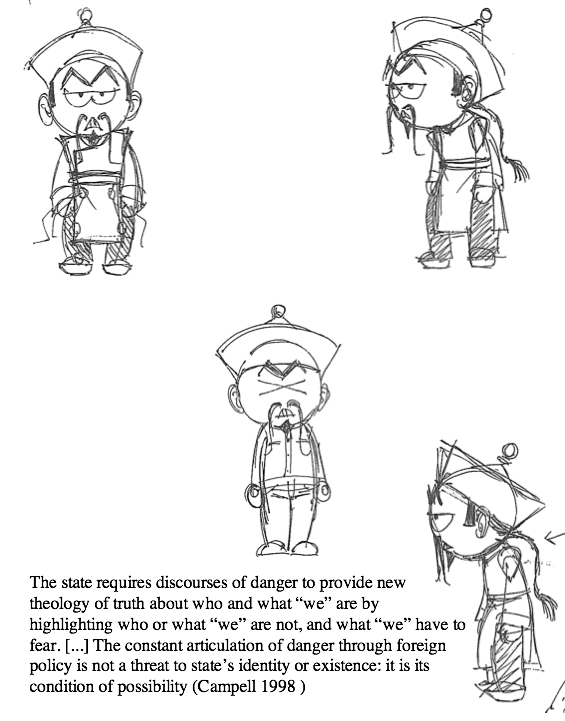

DY: This is a question I was more sure of before I started the workshop series – I feel the more I’ve gained an understanding of the way they’re used, the less sure I am of what needs to change. I see the drone as a symbol for the way conflict is understood post 9-11. It is part of the language, aesthetics, and transnational politics of the War on Terror. What is most concerning to me is the idea that the drone allows a state to fight a war while apparently sidestepping the otherwise necessary apparatuses of legality and oversight. As a covert weapon, it can be implemented in exceptional, extra-judicial ways that have not been legislated for as yet. The “targeted strike” and “signature strike”, while distinct from each other in protocol and circumstance, are particularly problematic – the former amounts to what many journalists describe as an assassination, although this word is rejected by the US government.

The CIA Torture Report released at the end of last year was an important acknowledgement of institutional subversions of legal and moral codes. I’d expect that a similar report into the use and effects of military drones would create space for an informed public debate about how they might be used in the future.

MG: Regarding you own relation and interests around drone and military culture, what are your plans in the near future?

DY: The outcomes of The Reposition Matrix have led me to approach this issue in a different way, looking for alternative ways of instigating conversations around this difficult subject. I’m still quite occupied with issues around the collection and presentation of data – during the workshops we covered a lot of diverse subjects, but always situating research outcomes on the surface of a world map. The question for me right now is what information is important to work with, and how can it be usefully represented? I’m looking at alternative methods of “mapping”, perhaps based in mapping technologies/software but using them in more disruptive non-geographic ways. I’ve been quite inspired by Metahaven’s ‘Sunshine Unfinished’ and the recently published book ‘Cartographies of the Absolute’ – both works have brought me back to some possibilities that went unexplored in the initial run of workshops back in 2013.

MG: What other projects are you involved in?

DY: Aside from this research, I’m currently collaborating on a project titled “Cursor” with Jake Watts and Kirsty Hendry as part of New Media Scotland’s Alt-W fund. We’re investigating current trends in fitness tracking technologies, and attempting to uncover and critique the way such intimate personal data is produced, distributed, and commodified. You can follow our research as it evolves on http://cursorware.me

I’m also running a space here in Edinburgh called Localhost, with the aim of stimulating discussions around the political aspects of digital art/culture. I run regular workshops and more occasionally special events, but I’m also very happy to provide a platform for others who wish to share their thoughts & skills on related subjects. Check http://l-o-c-a-l-h-o-s-t.com/ for more information and how to get involved.

Thank you very much 🙂

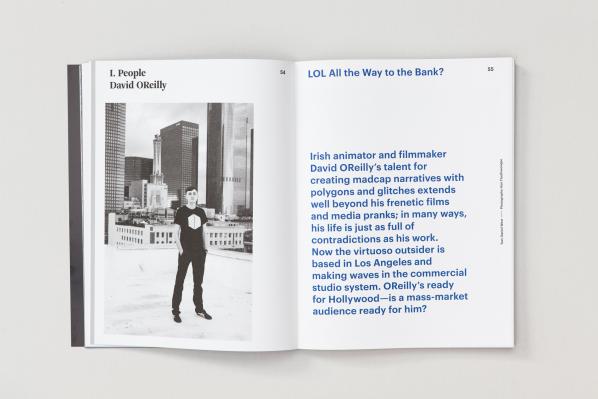

The American artist Patrick Lichty is best-known for his works with digital media: as part of the activist group RT Mark and as designer of digital animation movies for their follow-up The Yes Men, he has been recognized as a net artist with a political bend. He has been working with digital media since the 1980s, and has created works with video, for the Web and for Second Life.

At his solo show “Artifacts” at DAM Galerie in Berlin however, the artist, who is teaching at the University of Wisconsin in Milwaukee and has recently published a book with theoretical essays, does not show media works, but tapestries.

Tapestries? In the following interview Lichty talks about his return to traditional art techniques.

Tilman Baumgärtel (TB): Patrick, you are known for your work with media, and you have created 3D animations, Internet and Second Life works. But at your recent shows both in Berlin and New York you show works in much more traditional artistic media: drawings in New York, tapestries in Berlin. Why the return to these time-honoured modes of production?

Patrick Lichty (PL): I’ve been sitting in front of the screen for almost 30 years, and I’ve been blind several times in my life. This leads me to my belief that, “Mediation is reality.” I have artificial lenses, and I don’t know whether I see the world as it is. I feel like I have this cyborg vision, like I am slightly alien. I’ve had this feeling all my life.

So on the one hand, I have tried to create an alternative reality through mediation, or maybe to see the world for what it is through mediation. That is what happens with the Yes Men for instance: I am helping Mike and Andy to create alternative realities for our fictitious corporate campaigns. And on the other hand I am interested in what Marcus Novak from University of California Santa Barbara calls “Evergence” where virtual things that never existed except in the virtual manifest in the physical. It is almost like William Gibson’s novel “All Tomorrow’s Parties”, where the “printed” virtual J-pop idol Rei Toei idol jumps out of the nano-replicator, and says “Hello”, even though she never existed. I am interested in the tangible digital that manifests from the potential virtual…

TB: The tangible digital?

PL: Well, the idea of taking code, and turning it into 3D-objects, or taking things from Second Life and creating artifacts, and I use the US spelling as a double reference to “artifacting” or pixelization of an edge. The whole show here in Berlin is meant to introduce people to this gigantic body of work that I created in the realm of the digital as a cultural explorer, and that the contemporary art world doesn’t know much about, a bit at a time. What we have in the show are artifacts based on some of my more art world-friendly works. Some of my other pieces are definitely not art-world-friendly. I have done tons of prints and tons of video, that can be presented in a show, but a lot of my web work utterly and completely resists any kind of exhibition.

In the show in New York I have ten Roman-Verostko-like plotter prints of random internet cats, which is sort of my answer to post-internet art. By the way, you know what sold? The kitten swatting at the drone flying over it.

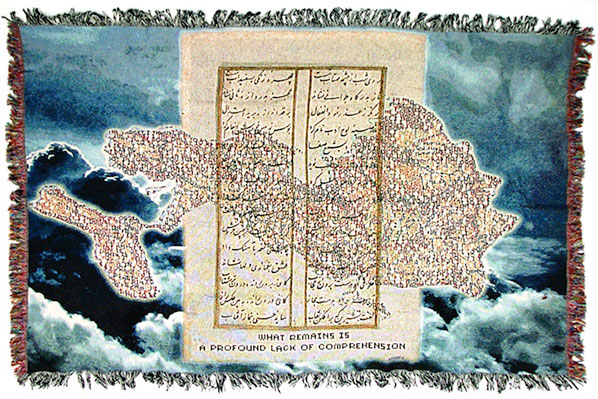

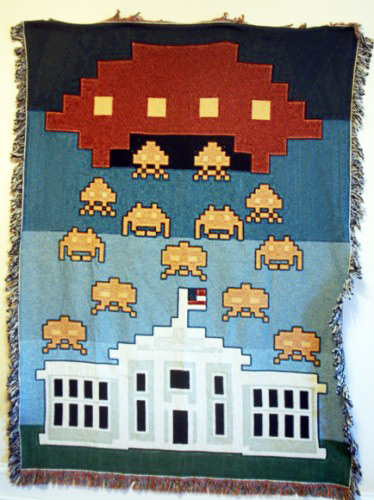

TB: How did you pick the motifs for the tapestry that is on display here in Berlin?

PL: This images come from certain key points in my practice in the last ten years. I send these files to a mill in South Carolina, and they fabricate the tapestry based on my image. These images are the ones that resonate with me very strongly. There is one that is called “Orange Alert”, which has the Space Invaders from the computer game attacking the White House, that I translated into this huge tapestry. It is based on a painting that his since been destroyed, and I think it is actually more interesting that way. We used to have this color code system in the US. “Orange” meant “You better be really scared”, and “Red” meant “You can kiss your ass good-bye.” Five years after 7/11, all the airports in the US were on Orange Alert, and nobody cared.

TB: Weaving was among the first crafts that were mechanized, and the mechanical looms were among the first machines that were controlled with early forms of punched card that in the early days of computing were the first form of memory storage. Is that the reason why you translated these images into tapestry?

PL: On the one hand I am referring to the old, grand art of tapestry weaving, and, maybe, playing a little bit to the gallery. It is a way to express the digital in a very certain kind of materiality that I find interesting and that is historically relevant to our heritage. They are simply a beautiful way to express digital content. And they are easy to display.

TB: The next thing we know is that you will be sitting on the loom again, rather than having these tapestries made for you…

PL: Well, I did that as a child. My mother was an artist and I worked on a loom with her. So there are specific incidents in my life that logically led me to create this work. I am not doing it, because it is hip, or cheap…

TB: …or could be shown in a gallery…

PL: No. There have been specific moments in my life that lead me to this, it was not merely a gallery move, although it made things easier.

The other thing that I am doing is that I am starting to place Augmented Reality on them, but that is not in this show. With the other Augmented works, like my Kenai Tapestry, you can take a device, bring up an app, and you look at it through the device, which recognizes the piece and then the virtual content comes out. The only piece like this in the DAM Berlin show that is like this is one piece that has a QR code on it that just says http:// and it sends you to a 404-error page. It is a Jodi-like piece. I don’t have to keep a server. It is something that actually does engage with technological devices, but I do not have to do this horrible upkeep.

I did a piece called “Grasping @ Bits” in 2000 for which I got a honourable mention for the Golden Nica at Ars Electronica. It was this terribly complex hypertext-essay with hyper browsers and multiple reading paths, that had to do with activism and net art. I did this 15 years ago, and it is almost broken. Unless QR codes become totally defunct, I hope the 404 piece will work for a long time. We still have barcodes after how many years?

TB: In the 1990s, people were thinking that we would somehow upload ourselves into “cyberspace”, as in the “Matrix” movies. What seems to happen now is exactly the opposite: The virtual seems to re-materialise by manifesting itself in physical space, via 3D printers, smartphones etc.

PL: Instead of “The Matrix” it is more like in “All Tomorrow’s Parties” or “The Diamond Age”, in which we have machines that turn everything into what Bruce Sterling refers to as “gomi” or clutter/trash in Japanese. We have this whole explosion of digital content becoming physical again, but to quote Sterling again, most of them are meaningless technical exercises, or “Crapjects”.

This whole issue of re-materialization and corporeality from media to physical objects is of growing importance to me. We are made of material/flesh (points to his arm) rather than this (points to a computer). Moravec hasn’t come true yet; we are not uploading ourselves anytime soon…

I had a phase around 2005, where nobody heard from me much for a year or two because I wanted to reconcile myself with material. I didn’t do much media art, it was mostly material practice. That was when I started to work with iron casting and weaving. I have been interested in the Jacquard loom and 3D printing since 2004, but I am only showing much of that now. I did a 3D representation of a gif in 2005, where the black and white value determine the height of the different pixels. White is high, black is low. I had that cast in iron. It is from a series called “8 Bit Or Less”, that reflected on my blindness. I took samples from the different series of my work and experimented with translating them into a physical form. The idea is that mediation becomes physical reality, and the format of this show is a survey of various works. I thought that was the most logical way yo introduce people to a substantial body of work quickly but in an accessible way.

TB: Let’s talk about your involvement with groups like RTMark, the Yes Men or Second Front. You said that you were interested in creating alternative realities. Was that the reason why you ghelped create these groups?

PL: I have always been a leftist, who – ironically – tries to survive on his work. That´s why I was attracted to the anti-corporate bent of RTMark and the Yes Men.

A little bit back-story is in order here: Imagine an electrical engineer raised by artists and then taught how to do Critical Theory by Ph.D.s in Sociology and Theatre History, and what you get is me.

I actually worked an electronic engineer for a while, and did not go to art school until I needed a degree to be an academic, as a lot of early New Media artists did. My mother was an artist, she trained me in the arts. I got my first electronics kit in 1970, when I was eight years old. And then I got my first computer and started drawing on it in 1978 – that was an Atari 800 (I still have it). And I got on the internet in 1983, 11 years before the web. So who is the “digital native” here?

I was doing computer art in the 1980s, but only started showing my work in 1990. By that time I had fallen in love with a theatre historian and through her I had fallen in love with theory. My best friend even to this day, Jonathon Epstein, is a sociologist, who got me interested in visual sociology. We started a collective called Haymarket RIOT that made Social Theory proto-meme gifs in 1990-94 which Baudrillard loved, by the way. Later, we did these post-modern social theory-based industrial rock videos that were all 3D-animated. And I send these to Jacques Servin and Igor Vamos, when they were about to found RTMark. They did a cross-country tour across the US as Igor moved to Troy, NY, and they came to meet me in Ohio. They told me what they wanted to do, and I said: “Wow, you’re weird!” So we started RTMark, and the rest is history.

RTMark then turned into the Yes Men. I am not so central any more, but I still do all the animations for the movies and interventions. I think they became so noted that it is hard for them to do direct actions any more. Their actions became sort of theatre rather than activism. I think that’s why there’s much more emphasis on things like The Yes Lab and The Action Switchboard, so they can empower other people. The “Action Switch Board”, by the way, reminds me a lot of a much more refined version of RT Mark’s “Mutual Fund”, but much more robust.

TB: RT Mark, The Yes Men, Second Front – it seems like you prefer to operate in groups rather than developing your own personal Oeuvre.

PL: Not really, but certainly that is what is more visible to the public. Because I live in this world of mediation, it’s almost as if these groups have been my social groups. And I have always felt that in regards to getting traction in the cultural milieu, there has been strength in numbers. In groups, there are more people to jump on the soap box.

However, since the time when we founded Second Front, I’ve been very vocal in keeping the group into an almost ego-less form, patially from my experience with collectives, partially by the Zen/FLUXUS influence Bibbe Hansen brought to the group. I wanted a way to keep our group as logistically “flat” as possible. Which is ironic, because now Bibbe Hansen is one of our members, who has this huge legacy. Right now we are doing performances of Virtual Fluxus. We are also exploring Al Hansen´s (and other historical FLUXUS artists) work in Second Life.

TB: Are you “re-enacting” them, which is a trend in the art world right now?

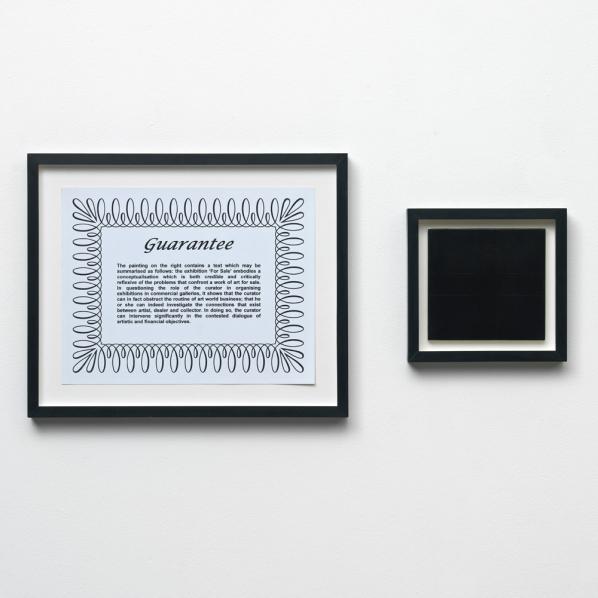

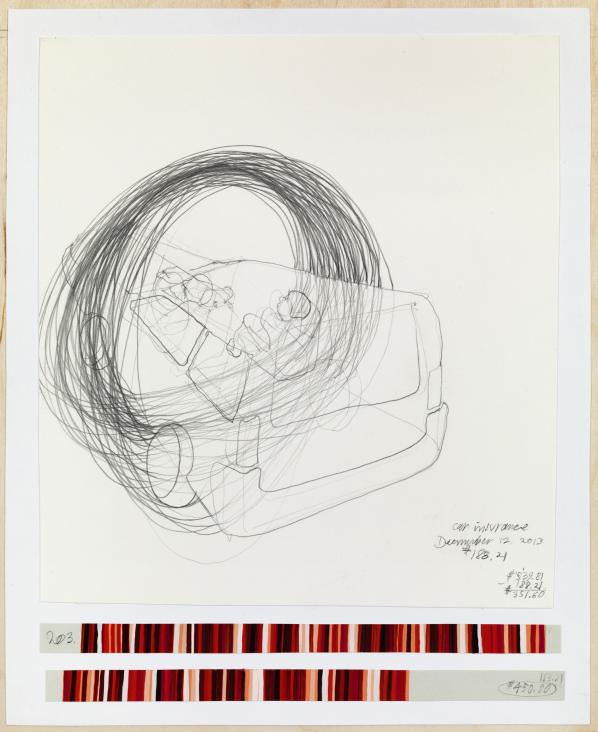

PL: I would say “re-mediate”. What we are actually doing is performing un-produced texts by Al, pieces that could have never been done in real life. So we are not re-staging, we are creating works that have been unrealized. That is pretty exciting. One piece we have been doing is “Car Bibbe II”, a successor to his performance “Car Symphony” from 1968 that was never realized because of liability issues. He wanted to explode some Cadillacs.

TB: Why are you using Second Life? There has been a lot of criticism because this system leaves little liberty to the users…

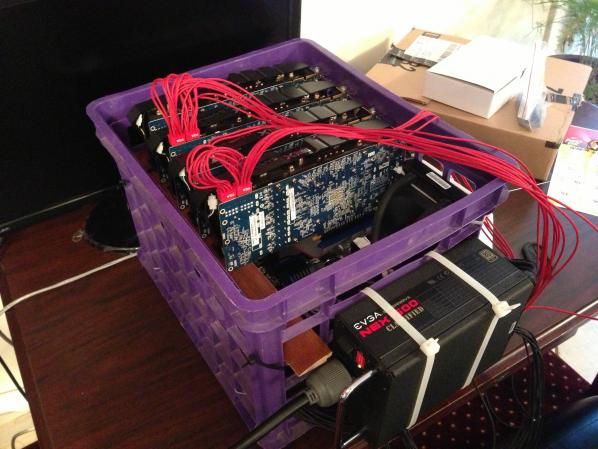

PL: It is actually very fluid. It has a huge amount of possibility. Yet, we are currently investigating “Open Sim”, the open source alternative to Second Live. Any of the money that we are earning with the videos I have editioned at DAM will go to buy a permanent server and a static IP. I don’t want to go to another server farm. I want a modem in my living room with our world on my computer. It will be cheaper, and then we do not have to deal with Linden Labs’ oppressive policies any more.

TB: The attractive thing about Second Life was that at one point there was a ready audience, because it was so popular. But I do not think that this is the case any more…

PL: The important thing is that we used to do it as a function of community, and now we are using it as a representational tool. So the main results now are prints and videos. We want people to hear the tree fall, and this the way we get people to hear the tree fall in the woods: We take videos of it. The community has changed so much, it isn’t as important to us as artists any more.

TB: Second Life seems like Atlantis these days – a sunken, forgotten continent…

PL: It is kind of a necropolis for old technocrats. It is actually a very cyber-punk-thing. It is “Snowcrash”, 15 years later. But I am very interested in using Jurassic technologies and doing Media Archaeology. I also work a lot with pixelization, because at this point we don´t have to have it any more; it’s a choice. I did these pixilated nudes, that are barely recognizable as figures any more. You know, every artist needs to have a phase, where he is doing nudes, you know? (laughs) So I wanted to make them materially manifest a couple of years ago by laser cutting them into wood, expressing their materiality as surely as flesh does.

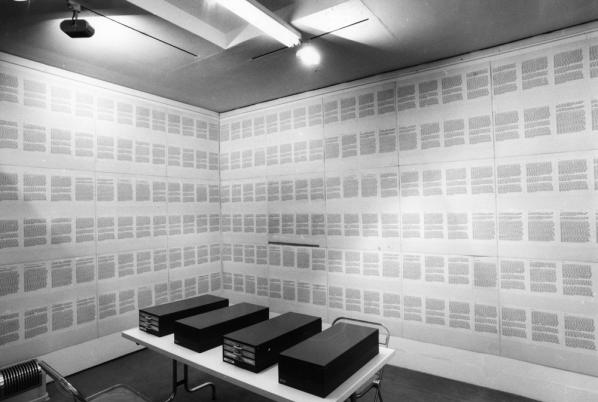

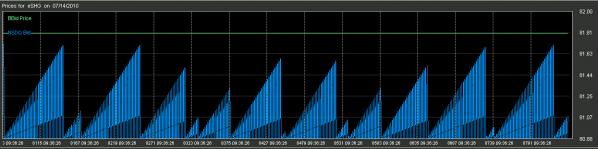

For the past ten years I have been doing media archaeological research into reviving Slow Scan Television as an art form. It is a video art form from the early days of Telecommunications Art. It is very low res, it only has four grey scales and a resolution of 120×120 pixels. It is a pretty specific and anachronistic art form. I am working with Hank Bull and Western Front right now to decode the audio track of the Slow Scan “Wiencouver” interventions of the 1980’s. I think I am one of the few members of my generation that knows how to run this equipment and how to repair these things. Many of my colleagues, who talk about dirty media and low tech, are still relying on the web… Well, they can have the Web. I am going back to networked art before the web. I am going back to the telephone network, but I use Skype now!

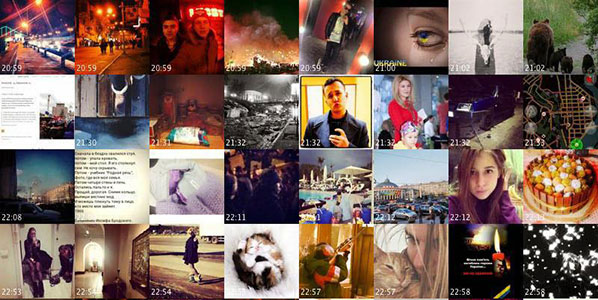

Featured image: 144 Hours in Kiev: Instagram montage, all images courtesy of Lev Manovich

Lev Manovich’s upcoming keynote, along with the entire Art of the Networked Practice online symposium, March 31 – April 2, 2015, will be free, open and accessible via web-conference from anywhere in the world. Visit the Website to register. The symposium is in collaboration with Furtherfield.

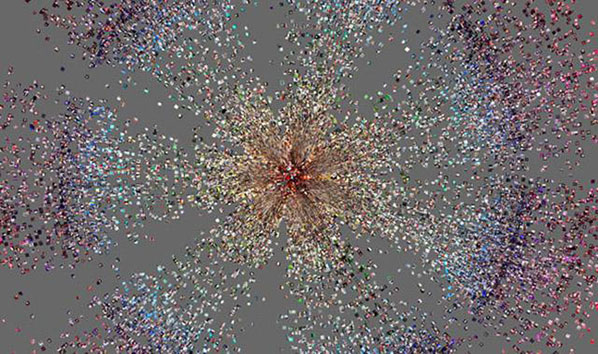

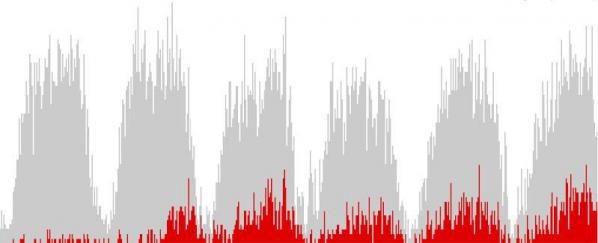

While big data has infiltrated our everyday lives, Lev Manovich and his collaborators have explored the data of everyday life as a window on social transformation. We discuss his latest work: The Exceptional and the Everyday: 144 Hours in Kiev, a portrait of political upheaval in the Ukraine constructed from thousands of Instagram photos taken over a six day period during the revolution in February of 2014. The project evolves from Manovich’s recent manifestations, Phototrails (2013) and SelfieCity (2014), metamorphosing social media into data landscapes.

Randall Packer: How do you view social media as illuminating a broader understanding of crisis in times of political upheaval?

Lev Manovich: When the media covers exceptional events such as social upheavals, revolutions, and protests, typically they just show you a few professionally shot photographs that focus on this moment of protest at particular points in the city. So we were wondering if examining Instagram photos that were shared in the central part of Kiev would give us a different picture. Not necessarily an objective picture because Instagram has its own biases and it’s definitely not a transparent window into reality, but would give us, let’s say, a more democratic picture. So we’ve downloaded over 20,000 photos shared by 6,000 people, and using visualization we created a number of different views of reality with patterns contained in the data. And we were particularly interested to see how the images of the everyday exist side by side with images of extraordinary events: how images of demonstrations, confrontation with government forces, fire, smoke, and barricades exist next to selfies, parties, or empty streets.

RP: Is it possible to think of what you are doing as taking an activist position in terms of revealing truths about a political situation?

LM: We have to be careful because obviously what you are seeing in 144 Hours in Kiev is a relatively small part of the population. Because the people who do use Instagram create tags mostly in English, they are, maybe, pro-Western people. But it allows us to get a sense of, not necessarily of a truth, not necessarily of what’s real, but let’s say a different kind of picture, a different place of reality then what the journalists would get. Because journalists may go, talk to a few people, and then come up with a report. But here you have “quotes,” so to speak, of thousands of people.

RP: Do you also see the collections of visualizations from user-generated images as an aesthetic realization?

LM: Perhaps one thing we can highlight is the idea of expressive visualization. As an artist I am also interested in the question of how can I present the world through the data. So let’s say a hundred years ago I would be taking photographs of a city. Now I can represent the city through 2 million Instagram photos. Thinking about landscape paintings in Impressionism, Fauvism, or even Cubism, how could I represent nature today through the contributions of millions of people? So I think of myself as an artist who is painting with data.

RP: But I’ve noticed that there is a focus in your writing on scientific methodology, you don’t talk very much about the renderings from an artistic perspective.

LM: It’s very clear that we’re taking ideas and techniques that have been used by modern artists. The difference is that we are pulling out data and writing open source tools. We’re taking in this case social media, works that were not created by us, and then putting them through different kinds of combinations. If you think about modernist collage of the city from the 1910s or 1920s, using pieces of newspaper and other existing media, what we’re doing exists in the same tradition.

RP: In many ways, the works can be fully appreciated as collage or composites, which I imagine goes against what you are trying to say through data analysis.

LM: No, it doesn’t go against what we are doing. It’s a matter of speaking to different parts of society. So you don’t just talk to designers or artists or like-minded people, you also talk to scientists. But ultimately what drives me is that I can I create something expressive, something unique, that isn’t just simply a data visualization, but creates an image that finds visual forms, that finds the right metaphors, which allows me to talk about modern society as consistent with its millions of data points. To me I think it’s a successful metaphor for how to speak about society today, when you think about all the traces you leave on social networks. I am trying to find the static visual forms to represent our new sense of society from seemingly random acts of individual people.

RP: Talk about the idea of “collective stories,” which are revealed in the composite of hundreds of thousands Instagram photos, each of which is a story in and of itself.

LM: We bring all these narratives together and try to make a kind of composite “film.” The connection to documentary, such as filmmakers like Dziga Vertov, for me is very clear. When Dziga Vertov, for example, was making his films in Kiev, he would have several cameramen in different parts of the Soviet Union shooting everyday, and they would send it to him and he would put it all together. So my “films” are made up of downloaded visuals, in which you can then make multiple “films” out of.

RP: Is it possible that the individual stories, the individual voice of expression, might get lost in this broad swath of data mining and cultural analytics?

LM: People are documenting what they think is interesting and important in their lives. But because there are very particular behaviors, what you get is a kind of pattern. I would say that patterns are not the same thing as a story. I don’t think of it as traditional narrative art, but rather a pattern of certain repeating behaviors.

RP: How do you position the work you are doing in the context of the current crisis of invasive surveillance and the loss of privacy resulting from big data analysis?

LM: When we started thinking about these ideas in 2005, these issues were not on the table. In the last two or three years they have become central and to be honest they keep me up at night. I consider whether or not it’s OK because there are histories of governments using photographs of protests of honest people. I think the first time it happened seriously was in Prague in 1968 when it was raided by the Soviet Union. You had bystanders taking pictures, and when the pictures were found they were used to arrest people. So we thought a lot about it. When you start to individualize stories, when you start following particular people, then it gets really dangerous.

RP: In this sense its a very political project. What you have done is revealed that in the 21st century of social media it’s difficult to hide anything. What have you learned about contemporary life as seen through the lens of social media?

LM: This is a deep question. I’m basically trying to say that as opposed to a journalist who thinks about the “data” as a kind of truth, that it’s a way to find out what happened, what I’m thinking about is its own reality. It’s not a question of truth, it’s a question of making interesting connections.

RP: That’s the difference between an artist and a journalist or even a scientist. You’re absorbing and you’re finding the connections but you’re not trying to say: this is it.

LM: I think the main answer is this: we can produce different visualizations out of the same data. Everyone views a different idea. It’s like when Monet paints another cathedral, there is not one painting that is correct. He makes a dozen paintings where every painting represents a different color, different atmospheric conditions, to show that in fact there are only the subjective views. So the goal is perhaps not to give people a new interpretation, but rather to challenge what they may be thinking is the correct one.

The Everyday and the Exceptional: 144 Hours in Kiev is a project of Lev Manovich in collaboration with Dr. Mehrdad Yazdani, Alise Tifentale, and Jay Chow.

First things first, Antonio Robert is a great guy. He is literally the happiest and most lively artist I’ve ever worked with, his online postings contribute in a full and proper way to both digital art and open source code communities, and he finds space in his wetware for the feedership of cats. He has top-notch glitch credentials, and is hooked into some important ideas about where that field is going – being the most active, if not only ‘glitch artist’ currently showing work in the UK. His work is rooted in glitch aesthetics and ideas, but constantly pushing at its edges. He’s performed and presented at Tate Modern, Databit.me in Arles, France, glitChicago, and he has his first solo show coming up at BOM (Birmingham Open Media) later this year.

Beside his happiness and energy, the first thing you notice about Antonio is that he has this geeky thing going on, like some kind of 90s Spielbergesque computer wizz – I’m sure I heard him call his computer ‘baby’ once as he goded it into action – but when he came to perform as part of our Syndrome programme in Liverpool, he literally ripped his tee-shirt off in the middle of the room, just as he was about to start.

He is the embodiment, in many ways, of the kind of volatility and fun in lots of great glitch art. I hooked up with Antonio online, where we spoke about glitch, and how it relates to his new iconoclastic work on copyright.

NJ: So… first question… You’re kinda out on your own in the UK it seems, as ‘the’ representative of the Glitch Art movement. I can see that that has been really great for you, for example with trips to Chicago etc… but does it also feel a little lonely?!

Antonio: Yeah, definitely. Ever since I helped bring the GLI.TC/H event to the UK/Birmingham in 2011 I’ve been getting questions about giltch art. I’m happy to impart my knowledge and experience to anyone that’s curious and my usual response is “you can do it too!”. That is, if you want to do glitch art there are so many tutorials about it. And, if you want there to be more events focused on glitch art all you need is an idea and some motivation.

NJ: There’s certainly an appetite for work which can reveal the systems underlying digital production – which is what good glitch art does. Do you think it is the term itself which is beginning to feel dated – as a result of an appropriation of its aesthetics? So fewer and fewer artists use this term now because its central modes are being used in a non-critical basis.

Antonio: I think it has become a bit dated through appropriation. That isn’t to say that glitch art has to be a specific thing and made using community-approved techniques, but now I see art that is just noisy or digital-looking that is described as glitch art.

NJ: I want to draw attention to some works of yours – or others – which seek out new (or different) systems which which to destructively engage. Because I think your work is still very much exploring and finding new territories opening up with this trope, while remaining within the ‘glitch’ genre. The work you made for the EVP website, “spɛl ænd spik:” modulated the construction of speech with phonemes. Where does the error enter into this, and do you consider it a departure from your work previous?

Antonio: It’s definitely a departure in terms of aesthetics.

NJ: It is not multicoloured!

Antonio: Hahah yeah. Even my clothes are plain. I wanted the focus to shift from the aesthetics of glitch. Glitch art incorporates many themes including randomness, error, helplessness, the unexpected, machine driven operations. And for the EVP piece I wanted to focus on randomness. I think the error lies in the perceptions of the viewer. When it was exhibited publicly at the Next Wave Exhibition at the RBSA many people thought that it was my voice and, at times, they could hear English words, so, the thing “glitching”, or experiencing an error in this case is their perceptions.

NJ: The tension between the random sounds and the possibility of speech is certainly unsettling.

Antonio: Then there’s the fact that those random sounds are coming from a human image… Digital and “New Media” art is still a new thing for many audiences and institutions, so confusion or bafflement is to be expected. I just hope that this then turns into curiosity. I hope that audiences then begin to ask questions about what it is they’re seeing and how it fits into their ideas about art, creativity and everything else.

NJ: There is something which Bifo Berardi says in “The Uprising: On Poetry and Finance”, where he is noting how ‘political decision has been replaced by techno-linguistic automatisms’, and it seems like ‘glitch’ art has a role to play here which is analogous to the one he assigns poetry in this book. Do you think that the kind of work you do with error is innately political or have revolutionary potential in this way?

Antonio: There is the overtly political work that I have made in the past. For example, Copyright Atrophy, which uses scripts and programs to challenge notions of ownership and copyright, was made specifically to be challenging, as was the work What Revolution. Another theme that interests me is copyright and free culture. And it’s always been there in my work, just not the core message. Now, for example, there is also the work about copyright which is currently being developed (as Archive Remix) as part of my residency at the University of Birmingham. It fits a long tradition of artists remixing artworks and appropriating culture. I’m hoping to bring about a change in attitudes at the university through my work with them.

NJ: Just looking at the work you’re doing at University of Birmingham, it seems to deal with the same theme as Copyright Atrophy, which is a kind of horizon of ownership – which relates also to the horizon of meaning… between meaning and meaninglessness, between owned and apprpriated. So there is a point in the logo-gifs of Copyright Atrophy, and the Archive Remix animations, where they are operating simultaneously as a symbol, or original – and as a new, catachrestic symbol for something yet to be defined. I’m taking the term catachresis here from the way Lee Edelman uses it in his literary and cultural criticism such as No Future, to describe how ‘misuse’ of given words leads to an opening up for heretofore undiscovered territory – also similar to what Rosa Menkman describes as Glitchspeak.

Antonio: Indeed. Although in Copyright Atrophy I am “destroying” the logos, in some way I’m evolving them too. I want to show that a piece of artwork is never truly finished as it may be reinterpreted and remixed by people, and also that we should let this natural evolution happen. Another example to illustrate this evolution is Comic Sans Must DIe.

Yes, I’m destroying each glyph of Comic Sans, but some frames of that might make a good new typeface in itself. The short animations I’m making for Archive Remix are, at the moment, acting as case studies that I will take to the university to show good things can happen when you have more liberal licensing on images. As you may have seen, I also do a version of the animations with the copyrighted material censored. I want to show the perils of censoring. So underneath each “new” gif is one with the copyrighted material blacked out. Imagine if DJ Shadow’s album Entroducing only had works that had been cleared for usage!

NJ: They are sad images, for sure. There is a melancholy at work here, which makes me think of the ‘death’ of the work, being the moment it has to stop evolving.

Antonio: Indeed.

NJ: I feel that way sometimes when I perform a poem, or even read it out to someone on the phone, that somehow its limitations have been reached as potential. Do you think it’s this attitude of a work always being open to interpretation which creates an exit from the inevitably melancholy ending of a completed artwork? I guess that’s one reason why an open platform for the code you produce is attractive.

Antonio: I can see the performance or exhibiting of an artwork as limiting because what has to be presented is something finished. However, sometimes I see this as a chance to exhibit one iteration of the work. It’s always open to myself or others to remake or build on from. There have been people that have built on the code and programs that I make and I’m thankful for this. The best example of this was the method I created for generating jpgs from random data, which was in itself inspired by HEADer Remix by Ted Davis. David Schaffer greatly extended this into his own tool and Holger Ballweg ported the code into SuperCollider. If any code I write inspires others who am I to stop them from using or building on it?

NJ: A year or so ago, I proposed that art forgery should be legalised. I feel, along with many others, that the ‘art market’ has very little to do with the community of artists most worthy of admiration and respect. But perhaps it is ownership itself that is the problem. What is there in ownership ‘authorship’ which is valuable to retain? Attribution, I suppose – but what value in attribution?

Antonio: Yes, attribution is the important thing. All people should rightfully own the thing that they make. But problems arise because they then want to own everything that comes after it. So yes, remixes, reinterpretations are important and should be allowed, just as long as the original author is attributed for their work. It’s all a confusing and scary time for artists and the art world. Everyone’s wondering how they can make money and sustain their practice whilst still reaching as many people as possible. I hope that through my work I can show that these new approaches (open source, free culture, liberal licensing etc) can yield positive results and won’t necessarily result in the loss of earnings or opportunities.

NJ: It’s kind of ironic though, isn’t it, that digital artists like yourself who actively question and disrupt the basis of the apparently ‘infinite flows’ of digital content, finance… are part of a scene whose infrastructure itself is crumbling, and who generally suffer a very real stress and insecurity as a result. This is exacerbated as well by the kind of funding environment which might be offsetting this instability somewhat, but where digital artists are co-opted ecosystem of ‘digital economy’ — rather than a ‘cultural economy’ — itself formed around ideas of efficiency, and hence ‘labour savings’? Do you think this might actually be harmful?

Antonio: Yes, I think it’s dangerous focusing just on digital economy and making everything digital. Sure, it’s exciting that technology brings us all of these opportunities, but it leaves behind everyone that doesn’t work in that way.

NJ: Finally, on this subject, I thought you might like to highlight some contemporary work which influences you, which comes from outside the ‘digital art’ scene (if this is even possible!) and thus contributes to the ecosystem of digital innovation, in more traditional forms.

Antonio: One of my influences was Arturo Herrea’s 2007 exhibition at the Ikon Gallery. I loved the way there was order in the chaos. Outside of that it’s really difficult to find examples of influential work that isn’t in some way digital. A lot of the live performance, sculpture and video work that inspires me is often not only made using digital technology – 3D printing, projection etc – but is about digital and internet culture.

You can follow Antonio on

http://www.hellocatfood.com/http://hellocatfood.tumblr.com/

and https://twitter.com/hellocatfood

and Nathan is at https://twitter.com/nathmercy

Featured image: Image from Joel Bakan: The Panopticon Power of the new media. Adbusters Jan 2012.

Marc Garrett and Ruth Catlow interview McKenzie Wark ahead of his keynote speech for Transmediale 2015 in Berlin this year.

It’s ten years since McKenzie Wark published his influential book, A Hacker Manifesto. Divided into 17 chapters, each offers a series of short, numbered paragraphs that mimic the epigrammatic style of Guy Debord’s The Society of the Spectacle. Wark then published, amongst others, a series of critically engaging books such as Gamer Theory and the Spectacle of Disintegration. Ruth Catlow and Marc Garrett from Furtherfield ask Wark how things have changed since these publications, focusing on how our everyday lives have been infiltrated by competitive game-like mechanisms that he described more than a decade ago.

Furtherfield: You published the experimental writing project Gamer Theory first as a book in 2006 and then in 2007 with a specially revised 2.0 version online.

Mckenzie Wark: Yes, although I think the network book version is mostly broken now. Good thing there’s a dead-tree format back-up!

F: In it you argue that we’re living in a world that is increasingly game-like and competitive. Also that computer games develop a utopian version of the world that realizes the principles of the level playing field and reward based on merit; whereas in the world, this is promised, but rarely realized.

MW: Yes, I think one way of thinking about certain games is that they are a fully realized neo-liberal utopia, which actually gives them some critical leverage of everyday life, which is a sort of less-real, only partially realized version of this, where the playing field is not level, where the 1% get to ‘cheat’ and get away with it.

F: You also talk of the “enclosure of the world” within the “gamespace” where the logics of the game are applied as the general patterns of organization in the world. And this happens as we adapt to the allegorical forms of contemporary games media.

How do you think this situation has changed since you wrote Gamer Theory?

MW: Well, to me it looks like the tendency analyzed in Gamer Theory became even more the case. GamerGate looks among other things like a reactive movement among people who really want the neoliberal utopia in all its actual neofascist and misogynist glory to not be exposed as different to everyday life. When women gamers or game journalists stick their hands up and say, “hey, wait a minute”1, they just want to mow them down with their pixelated weapons. So the paradox is that as gamespace becomes more and more ubiquitous, the tension between promise and execution becomes ever more obvious.

F: Do you see the term Gamification that many theorists use currently as an elaboration of the ideas you developed in Gamer Theory? Or are there significant new ideas being explored?

MW: Ha! Well no, gamification was about celebrating the becoming game-like of everyday life. So I always saw that as a kind of regression from thinking about the phenomena to sort of cheerleading for it.

F: The software developer and software freedom activist Richard Stallman, when visiting Korea in June 2000 illustrated the meaning of the word ‘Hacker’ in a fun way. During a lunch with GNU fans a waitress placed 6 chopsticks in front of him. Of course he knew they were meant for three people but he found it amusing to find another way to use them. Stallman managed to use three in his right hand and then successfully pick up a piece of food placing it into in his mouth. Stallman’s story is a playful illustration of “hack value,” about changing the purpose of something and making it do something different to what it was originally designed to do, or changing the default.2

Stallman was highlighting fun and the mischievous imagination as part of the spirit of what he sees as hack value.

Where do you see lies the hack value in games culture? What has happened to the fun in games? Who’s having it and where is it happening?

MW: Stallman is one of the greats. Sometimes, people have this experience of scientific or technical culture as one of free collaboration, where there’s a real play of rivalry and recognition but based on producing and sharing knowledge as a kind of gift. JD Bernal had that experience in physics in the 30s and Stallman had, I think, a similar experience in computing. I think it’s important for those of us from the arts or humanities to honor that utopian and activist impulse coming out of more technical fields.

There’s a lively, critical and even avant-garde movement in games right now. That’s part of why it has provoked such a fierce reaction from a certain conservative corner. The culture wars are being fought out via games, which is as it should be, as it’s one of the dominant media forms of our times. So there’s certainly some sophisticated fun to be had alongside the more visceral pleasure of clearing levels.

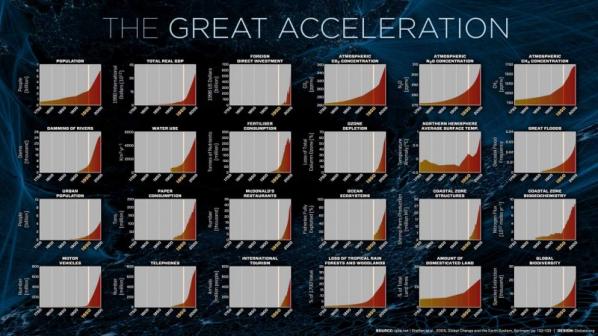

F: “Our species’ whole recorded history has taken place in the geological period called the Holocene – the brief interval stretching back 10,000 years. But our collective actions have brought us into uncharted territory. A growing number of scientists think we’ve entered a new geological epoch.”3 And, this new geological epoch has been proposed as – the Anthropocene.

In your essay ‘Critical Theory After the Anthropocene’4 you say “At a minimum, the Anthropocene calls on critical theory to entirely rethink its received ideas, its habituated traditions, its claims to authority. It needs to look back in its own archive for more useful critical tools.”

What are these ‘useful critical tools’ and how might theorists, new media artists, game designers and society at large put these to work?

MW: The ‘cene’ part of Anthropocene (from the Greek kainos) means a qualitative break in time. If time is in a sense always different, then kainos is the differently-different – a new kind of time. Those like Paul Crutzen who have advocated the use of the term Anthropocene to designate a new geological time have issued a major challenge as to how to interpret such a possibility. I leave it to the scientists to figure out if such a claim is scientifically valid. As someone trained in the humanities, I think the generous, comradely, cooperative thing to do is to try to interpret what our friends and colleagues in the sciences are telling us about the times. So in Molecular Red that was what I set out to do. Let’s take seriously the claim that these times are not ‘like’ other times. That I think calls for a rethinking of what from the cultural past might be useful now. I think we need new ancestors. Which is why, in Molecular Red, I went looking for them, based on the question: to which past comrades would the Anthropocene come as no surprise? I think Alexander Bogdanov, who understood a bit about the biosphere and the carbon cycle, would not be surprised. I think Andrey Platonov, who wrote about the attempts and failures to build a new kind of infrastructure for the Soviet experiment in a new mode of production would not be surprised. There are others, but those I thought were particularly helpful, not least because their Marxism remained in dialog with the sciences and technical arts. I don’t think the more romantic anti-science side of Western Marxism and continental thought is all that helpful at the moment, not least because it rules out of court exactly the kinds of scientific knowledges through which we know about the Anthropocene in the first place. The anti-science critique has been captured by the right, so we need new tactics.

F: Who’d be empowered by an encounter with your ideas and where do you see the potential for agency in the current economic and environmental contexts?

MW: Not for me to say really. Writers are usually the last people to have any clues as to what their writing says. There’s a sort of idiot quality to banging away on a keyboard. We’re word processors. Its always surprising to me the range of people who find something in what I write.

My hunch is that the future is in the hands of an alliance between those who make the forms and those who make the content: a hacker and worker alliance. It is clear that this civilization has already become unreal. Everyone knows it. We have to experiment now with what new forms might be.

F: And, where in the world do you see examples of individuals, groups and organizations, and or companies – who are putting into action some of the critical questions that you’re exploring in your writing?

MW: Besides Furtherfield? I never like to give examples. Everyone should be their own example. To détourn an old slogan of the 60s: be impossible, do the realistic!

F: In your later essay ‘The Drone of Minerva’5 you continue to write about the Anthropocene. But, you also bring to the table the subject of the Proletkult.6 The Proletkult aspired to radically modify existing artistic forms of revolutionary working class aesthetic which drew its inspiration from the construction of modern industrial society in Russia. At its peak in 1920, Proletkult had 84,000 members actively enrolled in about 300 local studios, clubs, and factory groups, with an additional 500,000 members participating in its activities on a more casual basis.

You are writing about the Proletkult in your latest book. Could you tell us a little something about this and how it will connect to contemporary lives?

MW: Proletkult was influential in Britain too, during the syndicalist phase of the British labor movement, up until the defeat of the 1926 general strike. After that the dominant forms were, on the one hand, the ethical-socialism and parliamentary path of the Labour Party, or the revolutionary Leninist party. Well, those paths have been defeated now too. I think we have to look at all of the past successes and failures all over again and cobble together new organizational and cultural forms, including a 21st century Proletkult.7 What that might mean is trying to self-organize in a comradely way to try and gain some collective charge of our everyday lives. It does not mean just celebrating actually existing working class cultures. Rather it’s more about starting there and developing culture and organization not as something reactive and marginalized but as something with organizational consistency and breadth. Since the ruling class clearly doesn’t give a fuck about us, let’s take charge of our own lives – together.

Thank you McKenzie Wark – Ruth Catlow & Marc Garrett 😉

Ruth Catlow will be at Transmediale 2015 CAPTURE ALL, moderating the keynote Capture All_Play with McKenzie Wark, on Sat, 31 Jan at 18:00.

Ruth is also participating in two other events, Play as a Commons: Practical Utopias & P2P Futures and The Post-Digital Review: Cultural Commons – http://www.transmediale.de/content/ruth-catlow

To many, technology and spirituality would seem antithetical. Contemporary technology is intertwined with modern science, whereas, spirituality is equally enmeshed within both religion and faith. The Post-Human Gospel self-consciously accepts this awkwardness, and manoeuvres these two uneasy bedfellows together. Offering up a night of performances, by artists whose entangled relation to technology seeks to posit new forms of identity and spirituality.

This is the latest in a series of events, collectively entitled Syndrome, seeking to explore the relationship between technology and affect in performance. The Post-Human Gospel marks the start of the third phase of this activity, collaboratively programmed by Mercy and The Hive Collective. If 3.0 is heading into the realm of spirituality, then earlier phases have played with both language and control – whether the constraints enforced on the body in virtual space, role-playing authority within the State Free State of a.P.A.t.T island, or a ‘room as instrument’ where you can physically manipulate sound and light. Across these events, those involved ask how we might interact or play with this technology, and in turn, how this experience might then act upon on us – our feelings and emotions?

The venue at 24 Kitchen Street has played host to several past Syndrome events, and as such feels like a hub for this activity as it meanders across the city. Arriving early there is a relaxed feeling to the space: people stand around chatting, whilst others tinker with equipment and final set-up, all bathed within the blue glow of the expectant projection screens. There is a familiarity to the space on a number of levels – not only physically, with decaying white walls and exposed structure typical of the post-industrial use of such buildings, but also in terms of its unclear typology, part-bar, part-residency-space, part-performance-venue, part-something-else-entirely. An earlier performer, Mathew Dryhurst, described a type of ‘third space music’ that requires a new type of venue. Something that Syndrome is clearly looking to create in Liverpool.

The evening’s Gospel was tripartite, starting with SHRINE by Outfit, followed by a first-time collaboration between Lawrence Lek and Siôn Parkinson, and then brought to a close with a live AV set by TCF. All performed from a improvised V-shaped altar – constructed from scaffold, screens, speakers and an array of other equipment – and oriented to the rows of the largely seated congregation.

A live performance-cum-guided-meditation, SHRINE was made in collaboration with the band Outfit and performed by lead guitarist Nick Hunt. Against the backdrop of a consistent electronic hum, the light of multiple projections alternates to produce a strobe-like effect. After the instruction to close our eyes, a distant reverberant monologue begins: “What is the meaning of asteroid? What is the meaning of baptism?” The warm flicker on the interior of the eyelid creates a soft trance-like state and the potential hypnotic suggestion washes over us. The minimal rhythmic repetition of this basic structure continues, but strays further and further from these initial references. What is the meaning of blurred lines? … Chandelier? … D-Day? … FIFA? Alliteration and rhyming abound. Selfie. Sophie. Stonehenge. Peter Pan. Quran. Ramadan. There is an emptying out of meaning, and a breakdown of language. KKK … K. The voice has a haunted quality, that of an entity in a state beyond being human. Perhaps it is the voice of the network, which the monologue refers to as ‘watching over us’, of ‘being busy’. It promises a revelation that is coming, that is now, another world, one that we don’t reach. Ultimately it leaves us cleansed, or rinsed out. Then I learn that the work was written with the assistance of Google Instant predictions, hence the alphabetical concatenation of words. Not so far from the network watching over us after all.

Lawrence Lek and Siôn Parkinson’s performance is the result of a short residency leading-up to the event, and therefore has a more involved relation to Syndrome. This residency structure is a recurring feature of the programme, with past residents including K回iro (Holly Herndon and Mathew Dryhurst), and before that Jamie Gledhill and Stefan Kassozoglou. Whereas these past examples involved existing partnerships, Lek and Parkinson’s collaboration was the first time that Syndrome brought together two artists, placing Parkinson’s vocal performance inside the digital landscape created by Lek.

A simulation of Liverpool’s Anglican Cathedral frames the performance, and provides an imagined perspective on this familiar architecture. Starting from a removed position – with the spectral cathedral in the distance – we roam through a wood, trees blowing in the wind. This landscape glitches in a way familiar to the experience of online or virtual worlds, and is accompanied by a soundscape produced by Lek on guitar and electronics. Gradually approaching our destination, bells peal, and further sounds produced begin to resemble those of an organ, groaning and droning as we enter its interior. Parkinson’s body is silhouetted against the projected architecture, his head bathed in red light and his voice rising as Lek’s audio recedes into the background. An otherworldly sermon tells of teeth wrenched out from a mouth to form the keyboard console of the church organ. Moving from sung to spoken word, to deep guttural noises. Rumbling bass emanating from the body, amplified, and shaking the room. Lek’s guitar returns, and there is the liquid crackle of noise as water rolls down the walls, and fire inhabits the projected interior. Our point-of-view rises high above the cathedral, and we see it situated in a landscape abundant with lakes and islands, like some stretched-out fantasy where this iconic building is removed from its physical context – as though transplanted from Liverpool to another world.

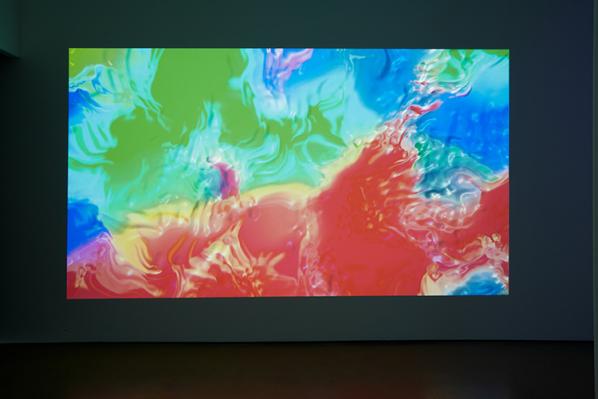

These mystical images continue through to the final performance by Lars The Contemporary Future Holdus (TCF). Projecting an increasingly entangled use of technology, he plays with encryption, code and algorithms to construct a subdued visual and sonic space. Twisted and distorted beeps shudder as fragments of sound screech and scrape along the digital surface, and liquid forms slip across the projected image. This precise construction appears to breathe, the sonic utterances repeatedly sucked back inside themselves as the molten amorphous form visually expands and contracts like something from within the bodily interior. There are moments where a mouth/voice emerges, a digital blob talking to us in a language that we cannot comprehend. Behind this audio-visual surface there is something else going on, something that Lars Holdus is engrossed within as he operates the TCF system – tinkering with the algorithm to progress through a series of potential compositions. Yet despite this, I feel largely disconnected – lacking in empathy – as though missing something in what is going on. There is an evident penchant for the opaque, that creates a distance between TCF and the audience, potentially even alienates. This is acknowledged by the artist, who states: “even the presentation is an encryption in itself. And therefore the people that won’t be triggered like that won’t access it.”1 I clearly fail to trigger, and my access is denied.

Syndrome is creating a space for artists, musicians and coders to experiment with work that merges electronic music and spoken word performance. The affordance offered by the flexibility of the venue has allowed an approach that would not have been possible within a space in daily use. These latest performative responses make clear that is it not about offering concrete proposals about what is going to happen, before they have time to come into being. Rather, what we witness is artists playing with the resources available, and figuring out what these things might do to us. There is a genuine openness and a potential intimacy to this approach, as well as the acceptance that the results will not always connect or affect audiences in the ways that they might be hope.

Different types of voice seem central to the three works presented within The Post-Human Gospel, affecting the human vocal output as well as trying to give voice to instruments, electronics and digital space. There is something in this that Holly Herndon has described as a “fleshy approach to machinery”, where these digital tools can take on a post-human quality, one that can become or embody different identities. This looks set to continue with the forthcoming event Brain/Music Experiments where artist Dave Lynch, neuroscientist Christophe de Bezenac and deaf classical musicians Ruth Montgomery and Danny Lane explore the ways a brain wave scanner can contribute to live music and visual performance.

The intention for Syndrome is to learn from all the visiting artists and the performances they create in this exploratory year. Looking for moments when performances create affective interfaces to communicate with people. Where they speculate on, or re-conceive, the relationship between human and technology. If they go on to develop a new live experience with the artistic community that surrounds Syndrome – as they suggest they will – I look forward to experiencing how the cumulative knowledge built up through these earlier events is harnessed to final affect.

Featured image: Stern, Body Language

Interactive Art and Embodiment: The Implicit Body As Performance by Nathaniel Stern. ISBN 978-1-78024-009-1 (printed publication), Gylphi Limited, Canterbury, UK, 2013. 291 pp., 41 Colour Stills.

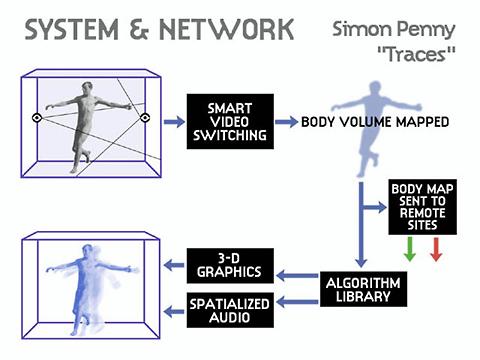

Earlier this year, I had the good fortune to sit in on a talk given by Simon Penny on May 6th 2014 at the University of Exeter. Penny, not unlike Nathaniel Stern, is best known for his praxis, writing and teaching on interactive (and robotic) installations focusing on issues of embodiment, relationality and materiality. So as unorthodox as its inclusion is to start off a review, Penny’s reflections are pertinent here (in this case, Penny’s famous installations Fugitive (1997) and Traces (1999) [1].