In the second part of this two-part interview series Carleigh Morgan interviews Jussi Parikka about Burak Arikan’s work, discussing the way data and networks condition and construct the way we view and interact with the world. The first part of the series, an interview with Burak Arikan, can be read here.

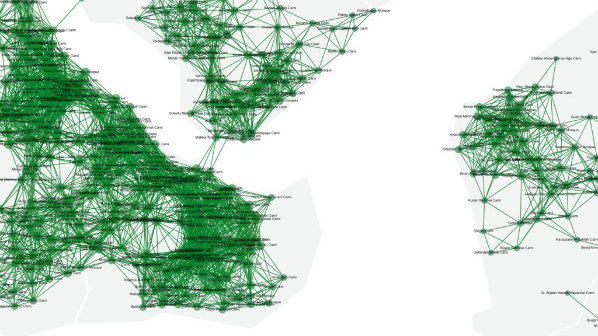

Burak Arikan is one of Turkey’s leading media artists. Through his practice he maps relations of power and invisible infrastructures using network mapping tools. Arikan’s Graph Commons, an online network mapping tool, is an open platform for the creation of networks that encourages its users to explore the functional limits of network architectures as a mechanism for storytelling, data visualization, and modelling our contemporary moment, from graphing financial microtransactions to mapping superstructures splayed across a continent.

Arikan’s most recent body of work, Data Asymmetry, was hosted at the Winchester School of Art from November 10-24, 2016. The exhibition was curated by new media theorist Jussi Parikka (Professor in Technological Culture & Aesthetics at Winchester School of Art) who comments on the themes, provocations, and challenges that this show invites its audience to consider.

CM: In your essay New Materialism as Media Theory, you conclude: “I propose a multiplicity of materialisms, and the task of new materialism is to address how to think materialisms in a multiplicity in such a methodological way that enables a grounded analysis of contemporary culture. Such methodologies and vocabularies need to be able to talk not only of objects, but also as much about nonsolids and the processual…so we can understand what might be the specificity of this brand of materialism that we encounter (but do not always perceive) in contemporary media culture.”

Are network visualizations like those in Burak Arikan’s art practice—for example, Islam Republic Neoliberalism, which organises data collected about the urban infrastructure—one way to capture the materialism that “we encounter but do not always perceive”? Are networks as a vocabulary sufficient to do this, and are these limitations to Burak’s methodologies that alert us to this kind of multiplicity of materialisms that cannot conform to the network graph?

JP: The network is one form of seeing the world; it gives one form to things we might sense around us as intuitively present even when we are not sure how to express that. The network is not necessarily an end in itself but one particular frame through which to map things – such as urban transformations, architectures as they pertain to our lived experience – and allows you to put yourself on that map. I don’t see networks as an overarching ontology but as a methodological entry to those relations that then scale on other levels too: experiences, narratives, etc. What’s interesting is how Burak’s work plays out this network relationality not only as a visual reality to be looked at, but as a collective form of doing: how to build a network through workshops, or how to express things that we feel crucial to our existence, especially in some of the more politically oriented activist works.

CM: Networking mapping seems to cover a range of modes: cultural epitome, critical methodology, data visualisation tool, a kind mediation narrative etc. Is there a danger to the multiplicities and modalities of representation that networks capture, namely a danger of being misused or misunderstood?

JP: I remember earlier discussions with Benjamin Bratton where we discussed “big data apophenia”: a particular sort of disorder that is conditioned by data: namely, to see relations and to establish them, even if they are not necessarily as real as one can infer from data. The same thing pertains to network methods: you could use it as a pataphysical tool as well to create imaginary worlds of relations, to offer causalities across logical relations, and to create as such a speculative alternative world. Oddly enough, this is exactly something that speaks to the now hot topic of “post truth politics”: how to manipulate and cater data and “information” in ways that becomes effective whether true or not. We are in any case talking of such methods than can be mobilized for multiple uses.

CM: “To produce maps is a method of mapping power, addressing by visual means the asymmetry that defines our situation. Not only asking where we are, but inquiring: where is our data and who owns your data trail? This exhibition maps the shift from information asymmetry to data asymmetry, where aggregation of data is where contemporary power lies.”

Do you see network mapping as inherently emancipatory? Is the need to orient oneself via networking mapping also an exercise in self-reflexive targeting, one that uses modes of surveillance and data capture in an attempt to evade those same modes of capture executed at the level of the corporate-state nexus–is this a contradiction and a risk worth taking in order to achieve an orientation within our own data?

JP: It’s a great point—and demonstrates the paradoxes in this sort of activist work. It’s pretty much a necessity to engage head on and inside such techniques to understand their work: the critical distance often required in institutional or political critique is not really sufficient if we want to understand data culture. We need to be able to work inside such techniques and data, also institutions, in order to be able to shift, transform and manipulate those tools to other ends.

CM: Any other comments on the Furtherfield show and Burak’s body of work?

JP: For us it was a really pleasurable opportunity to bring an internationally known artist’s work to Winchester Gallery, and exhibit work that is at that interesting triangle of activism, contemporary media arts and issues that we discuss in media and network studies. Hence while the exhibition was on in the gallery, we also wanted to expand it into other forms of work that build on our earlier collaborations, like at transmediale where we also had Burak as our guest. We also introduced his work into workshops we organised in Winchester and London. It’s this sort of dynamic exchange that also make his works alive: his practice does not merely look at maps and visual relations of data, but also engages, understands, and uses them.

—

Burak’s visit was part of our AHRC funded project Internet of Cultural Things but also our new research group, or office “AMT”: Archaeologies of Media and Technology.

Burak Arikan’s most recent body of work, Data Asymmetries, was hosted at the Winchester School of Art from November 10-24, 2016. His network mapping tool, Graph Commons, is viewable here.

*Inline image photo credits: Olcay Öztürk

Feature image: Winchester School of Art Exhibition of Data Asymmetries. Image Credit: Olcay Öztürk

Burak Arikan is one of Turkey’s leading media artists, a figure who straddles the lines between technologist and practitioner. He explores relations between data and transactions, the regimes of datafication and identification as control, and maps relations of power and invisible infrastructures with network mapping tools. According to new media theorist Jussi Parikka, Burak’s pieces “raise questions of the predictability of ordinary human behavior with MyPocket(2008); reveal insights into the infrastructure of megacities like Istanbul as a network of mosques, republican monuments and shopping malls (Islam, Republic, Neoliberalism, 2012); remap and organise recurring patterns in the official tourism commercials of governments with Monovacation (2012); explore the growth of networks via visual and kinetic abstraction with Tense (2007-2012); and showcase collective production of network maps from the Graph Commons platform.”

Burak’s creation of the Graph Commons, an online network mapping tool, is an open platform for the creation of networks that encourages its users to explore the functional limits of network architectures as a mechanism for storytelling, data visualization, and modelling our contemporary moment, from graphing financial microtransactions to mapping superstructures splayed across a continent.

Burak Arikan’s most recent body of work, Data Asymmetry, was hosted at the Winchester School of Art from November 10-24, 2016. His network mapping tool, Graph Commons, is viewable here.

In the first of this two part interview series, Carleigh Morgan speaks to Burak Arikan about his practice. In the second part of the series Morgan interviews Jussi Parikka about Arikan’s work and the way data and networks condition and build the way we view and interact within the world.

CM: The aim of the Graph Commons is to “empower people and projects through using network mapping, and collectively experiment with mapping as an ongoing practice.” But every visualising methodology has its hermeneutical blindspots and invisible shortcomings.

With those boundary constraints and affordances in mind: What are networks in art, and how are they are extensions of or departures from the networks that they attempt to depict?

BA: I use network as a map vs network as an event separately in my work.

Network as a map is simply using dots and lines to represent observed or measured relationships in order to explore the structures of rather complex systems in life. For example, I am interested in revealing the institutionalization without walls in the world of art, so I look at relationships of artists exhibiting together with other artists, art institutions related by the artists they show, influence of collector-artist relations etc. Such network mapping reveals central actors, indirect connections, organic clusters, structural holes, bridging actors, outliers etc. Network mapping provides a view of such qualities about that particular art world that you wouldn’t see otherwise.

A network map is both a visual and a mathematical language, that you can visually follow dots and lines with your eyes, as well as apply calculations on this data diagram. When you simply record and measure activities as data points, then you can link them to generate more insight and value from the linked whole than the sum of its parts. This is typical data linking method is commonly employed in security, marketing, finance, and social media industries by governments and corporations. One position I have in my art is to use such data mapping and analysis capacity on power relationships, mapping the ones who are mapping us. No need to say, my work is not necessarily about the internet of art things, but I’ve been interested in revealing the relations at scale in variety of fields ranging from juridical systems to cinematic languages.

Network as an event is a living substrate, it is people hanging out together, machines transmitting data packages, neurons firing signals, online platforms for social networking, physical ecosystems of humans and animals where widespread infectious disease can occur. These are physical, digital, hybrid living and multilayered systems maintained by diverse interactions between independent agents, where their small interactions governed by certain protocols together constitute an ever changing larger whole. Building a living network, or network as an event is another line of effort I’ve been pursuing in my work. For example, in 2007 I’ve built Meta-Markets, an experimental online stock market for trading social media profiles, where users did IPO (Initial Public Offering) their profiles and traded with others, with a goal to evaluate the value of a social media profile, the information you cannot get from the service provider company. It ran for 2 years and a community of members formed a dynamic trade network among a couple of thousand social media profiles.

CM: What types of agencies do network maps engender their makers with, and what kinds of constraints to they bring to bear on their creators? As an artist who works with the form of networks, have you witnessed a formal re-alignment of your thinking to reflect these structures? Through ongoing interrogations with and construction of networks as an aesthetic model, would you consider yourself more alert to the networks that condition our contemporary moment?

BA: As with any research, network maps are subjective too. Because by just measuring a reality you claim a subjective position. Thus, data points are always generated, rather than collected. Furthermore, network diagrams are usually totalizing and contemplative. As McKenzie Wark writes criticizing Frederic Jameson’s cognitive mapping: network maps freeze into a contemplative totality that prescribes an ideal form of action that never comes.

My network mapping work starts with raising new questions on critical relations that scale. Then I conduct research to generate data about a “particular world”, which enables many stories, interpretations, and use cases.

As a response to the lack of the “dialectical” in the frozen totality of static diagrams, I started using algorithmic interfaces in my installations. Such interactive network maps let you touch and change the positions of the dots on a map, yet browse the names without losing their relationality to each other as the software simulation continuously organizes the network layout. This way, normally invisible relations not just become visible, but also touchable, which enables us to effectively explore the chain of influences and relationality at scale. Touching the nodes also displays information cards, where you can get richer information about individual data points. By using an algorithmic interface you navigate back and forth between an abstract large picture and concrete juicy details of a complex issue. I think such encounters help the viewer to effectively interrogate the particular issue at hand and develop better insight. This aesthetic and pedagogical experience of interactive cartography is very different from a static diagram, that still lacks criticism.

CM: There’s a resounding common thread in your work [the mapping of the urban infrastructure of Istanbul in terms of its mosques, malls and national monuments in Islam, Republic, Neoliberalism demonstrates this clearly] that seeks to articulate the imbricated matrices of politics, art, and the practices of everyday life that are often not apprehensible to the individual occupied with the attention-consuming projects of being and living.

How does your work position the actor within the network, and what kinds of political commitments do you see expressed from your position as the authoritative designer/person who captures these networks in artistic form?

BA: Since a network map provides a world rather than a story and is thus a nonlinear medium, there is no flow of introduction, development, and finalization, neither a single story. So you start exploring a network map from a “you are here” point, a familiar name or an interesting image, which may be different for every other viewer. Then you do an unplanned journey through a topology of connected information points, navigate from one connection to another. You experience a traversal, a situationist dérive on a data network.

In my workshops and lectures I tell people not to use network mapping against themselves. Network mapping is a powerful tool, it makes structures transparent. Keep the maps about yourself to yourself. Turn it around and map the ones who map you.

In fact, when you click on a follow button, swipe a metrocard, or use your credit card your data is being captured and mapped by data-driven oligarchies. Obviously, this is not just a concern of privacy violation, in this day and age, data capturing is about ownership and control, thus capital and power.

CM: MyPocket generates data from bank transactions, Monovacation from tourism commercials, Islam Republic Neoliberalism organises data collected about the urban infrastructure, Tense Series generates semi-random numbers and uses it as data.

How does your work foreground how data–as algorithmic material that exists at the level of computation, below the thresholds of human apprehension– conditions and structures the world we live in?

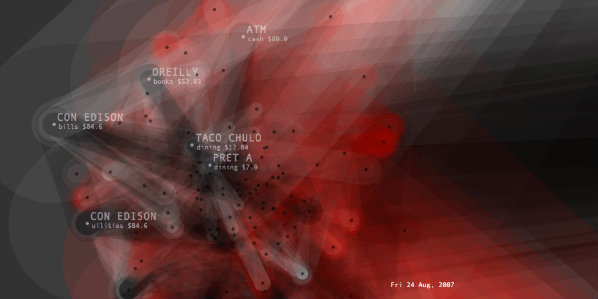

BA: Data about us, metadata, make our everyday behaviour more predictable. No one wants to live such a boring predictable life. In MyPocket (2008), by predicting and publishing what I will buy every other day, I demonstrated how easy it is to algorithmically predict our mundane behavior. With this work, in a way I sacrificed myself by making my data no more exclusive to a bank but available to anyone else, so that you can start thinking what corporations can predict about yourself and what it might mean to you.

By turning data around, we can reveal systematic yet invisible power structures. For example in 2012, I mapped a network of Istanbul’s 3000 mosques based on their overlapping call to prayer sounds. Most people living in Istanbul are born into this and take it for granted. However, the mosque network constitutes a subtle power structure, which became quite apparent to many as the government used this network to make calls to city squares in the days following the coup d’etat attempt on July 15th, 2016.

In most of my mapping work, I simply investigate data about one critical relation that connects many agents and constitutes more power as it scales. When completed, a data network is formed and I put that particular world to use.

CM: MyPocket discloses your personal financial records to the internet public by exploring essential patterns in your transactions and deploying software to analyse those transactions. The software, which predicts future spending, sometimes determines your future spending choices. Mark B Hansen calls this a “feed-forward” relationship—one where statistical forecasting, future prediction, and probability calculation can code user behaviour “ahead of time,” framing the future-oriented choices of a subject.

What is an example of a consumer choice you’ve exercised that you were directly influenced to make by this software prediction? Did knowing that your personal financial data was being tracked impact your financial management or change your spending behaviors at all?

BA: MyPocket software was able to successfully predict when and where am I going to buy coffee. It predicts ordinary futures. Our lives have such repetitive patterns, which are not so hard to guess right for a supervised algorithm. With MyPocket, I put myself in an experiment of living under excessive forecast about my everyday purchasing behavior. Would I change my habits, would I abide by the predictions, would I care, would I notice, would I ignore? All of these applied at various stages as I lived with this software system for 2 years.

Today, protecting your privacy is akin to quitting smoking or exercising a vegan lifestyle. Changing habits is clearly hard, but once it starts rolling, it causes a big positive change. I believe, in a society of control that monitors, simulates and pre-mediates individual identities in relation to their data trails, behavioural dissidence is superior to reactionary resistance.

CM: You are an artist and technologist. Does one of these identities emerge more frequently in your work? Did your programming skills drive you to explore the aesthetic possibilities of networking mapping? Was there a sequential logic to your artwork as a secondary and subsequent extension of your work in the computational sphere? How do you situate your artistic practice—one that is reliant on a high degree of technological literacy—to the tools of computer technologies?

BA: My art making is a subjective exploration raising questions, whereas my tool making always wants to be objective, tapping an issue with a solution. I practice them in parallel and they feed each other. Making tools helps me examine all kinds of infrastructures closely thus provides lenses for new questions in my artwork. Artistic inquiries help me change my beliefs about the world.

In the first class of an introduction to computer programming course at MIT, students are told that programming is unrelated to computers in a way that geometry is unrelated to geography. Mastering programming takes years. In fact, in my very early work, technology and algorithms had authority on the outcome, whereas later works have been freed from technological capacities.

BA: Do you find that the procedures for mapping with non-digital tools change your artistic strategies and the types of networks you produce? In a similar vein, is the medium of Graph Commons as a digital interface important to the co-collaborative possibilities that this online platform enables? Would you describe the network mapping that Graph Commons enables as an act that is inherently political, or aligned with activist models of representation?

BA: I always start modeling an idea by sketching on a paper, by discussing with people, by taking notes here and there. It is often a contemplative process that I don’t find possible in a digital tool. As the idea gets mature, the amount of related material might not be manageable on paper – then I start organizing it using digital tools, write some code to scale it and observe its extents.

Obviously, digital tools on the Internet are best for asynchronous communication. The Graph Commons data mapping and publishing platform is great for internet-scale data mapping collaborations. Network mapping particularly is a powerful tool, it makes things more transparent. So activists, journalists, researchers, and civil society organizations around the world use it to untangle complex relations that impact them and their communities.

CM: Do you see networks as maps? Monovacation seems to deploy features of both in its networked parody of the commodity forms and repeated images that characterize the tourism commercial as a typology. What are some key distinctions that might separate these two forms from one another in their attempts to frame, visualize, and enclose data?

BA: As I mentioned earlier, I use network as a map vs network as an event separately in my work.

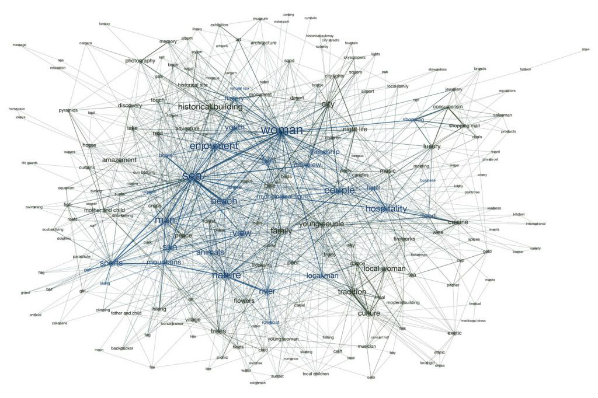

Monovacation introduced network traversal as a method to deconstruct and explore movies as databases. The official tourism commercials of countries in competition with each other have been selected and each film has been divided into the possible tiniest clips. The 3-4 second long clips have been coded with tags. Tags with shared clips are connected to each other (weighted with number of clips) on a network diagram, which runs as a self-organizing software simulation. A new movie has been algorithmically generated through a traversal on this network map, a program navigating from one node to another, following the weighted path among the tags. Seashores from Egypt to Portugal, women from Israel to India, mythological figures from Thailand to Turkey formed an extracted fantasy of “vacation”.

CM: The Graph Commons platform contains an additional axis that static graphics do not: time. How does working within digital media open up new models for orienting the user within data collections, particularly where the ability to represent change-over-time is at play?

BA: Networks are inherently dynamic, undergoing constant changes, both within the composition of nodes, and in the relations between nodes. To help you understand how the network changes and behaves over time, Graph Commons provides a timeline interface. It animates your network map as nodes leave and enter the network and the map expands or contracts in time. The network shape, radius, density, intensity, and emergence of clusters, central and peripheral actors all become observable and comparable using the timeline feature.

CM: Networks are the predominant and paradigmatic episteme of the information age. What kinds of relationalities, phenomena, data collections, or texts do they fail to capture? In other words:

a. What the network is NOT suited to do/perform

b. On speculating through an accelerated lens, what will the predominant formal and organisational structure of the next century look like? Will networks continue to play a role, or will they be completely surpassed by new organisational and structural logics?

BA: Bare network mapping may not be sufficient in studying multilayered diverse network dynamics where actors (nodes) and relations (edges) is not clearly distinguishable from one another as in swarms of species or molecular activity. Moreover, at the heart of capturing data lies the question of measurability. If something analogue can be measured it becomes digital, then it can be linked to other data points and become a subject of a network analysis. I think in this day and age, even emotions, intentions, and desires could be measured to a degree, if not socially reproduced.

In a world where every atom can be addressable with an IP address (IP6), discussion of the possibility of capturing analogue things is increasingly less relevant. What becomes critical is the question of who captures and controls what data owned by whom. Do you own a self-driving car’s data captured from your neighbourhood? Are you in control of your data captured by the network medicine? Are you paid rent for the use of data that belongs to you? Data oligarchies will only continue to grow, and this situation of data dispossession will increasingly constitute what I call data asymmetry for many years to come, until we move from connectivity to collectivity, build purposeful exploitation-free autonomous zones, and reroute our life activities in solidarity.

Regarding the future of organizational structures as imagined to be constituted by cryptocurrencies, something clear from today is that decentralization is not necessarily democratic. It should be deliberately discussed that ones who design the protocols have power and network effects can generate inequality. A blind belief in decentralization would not be so different than a belief in free market ideology. When Poland, Chile, and Turkey opened their markets to the world in the 80s, globally networked corporations penetrated into these markets completely within the laws and yet left the small locally connected actors stagnant, this is one example how network effects could generate inequality.

Featured image: “Binoculars” at CHB in Berlin (2013)

Varvara Guljajeva & Mar Canet have been working together as an artist duo since 2009. They have exhibited their art pieces in a number of international shows and festivals. As an artist duo they locate thermselves in the fields of art and technology, and are interested in new forms of art and innovation, which includes the application of knitting digital fabrication. They use and challenge technology in order to explore novel concepts in art and design. Hence, research is an integral part of their creative practice. In addition to kinetic and interactive installations, the artists have also experience with working in public spaces and with urban media.

Varvara is originally from Estonia, and gained her bachelor degree in IT from Estonian IT College, and a masters degree in digital media from ISNM in Germany and currently is a PhD candidate at the Estonian Art Academy in the department of Art and Design. Mar (born in Barcelona) has two degrees: in art and design from ESDI in Barcelona and in computer game development from University Central Lancashire in UK. He is also a co-founder of Derivart and Lummo.

Filippo Lorenzin: Open culture is one of the main points of your research and activity. Could you describe how this influences your art practice?

Varvara & Mar: We are living in very exciting times. Open source has introduced democratization of production and creation. Now you can build your own 3D printer, laser cutter, knitting machine, make a light dimmer circuit or develop a body tracking system. Some years ago we couldn’t even imagine this and now we have access to this knowledge. People share their creations and these process, which is incredibly inspiring for us and many more people. Thus, knowledge is built on top of knowledge. We make use of open source marterial in our work and we try also to contribute back. This is the whole point of open source in our mind. And if one looks in the perspective of art to open source projects, then really many open source projects have artists on board, for example, OpenFrameworks, Processing, and more.

Open source also has an educational aspec. We do many workshops with people and teach what we know and how we work. We think open source culture is largely based on the spirit being open to sharing knowledge with many others.

FL: I’m really fascinated by your interest in textile fabrication. it reminds me the early industrial developments that were deeply connected to in the textiles industry. How and why would knitting be integrated these days as part of a makers’ culture?

V&M: The process of integration is well under way. There has been a good number of makerspaces who have dedicated areas for textile production, like WeMake in Milan and STPLN in Malmö. And believe it or not this simple thing helps to introduce gender balance in these kind of places. We’re not just talking about innovation, which can boost gender equality when you introduce knitting to hacking. We’re also talking about the democratisation of production, when thinking about clothing too. This area is quite vital and commonly understood. 3D printing toys is a cool activity for a weekend, but then it becomes boring. Knitting a sweater or a scarf has real value and the quality is always higher than a typical mass produced factory product.

For 3D printing we cannot say the same. Don’t get us wrong, we are not against the 3D printing. We love it and have six printers in our studio. Our point is that the areas of concern for digital fabrication are not complete, and the founders of FabLab have overlooked the whole area of textiles.

FL: You’ve run many workshops taking in account various topics such as 3D printing, solar energy and knitting, of course. How do these activities connect with your research?

V&M: First of all, we like to teach and interact with our students. Second, preparing a workshop, allows us to research more about the field, and organise and share our accumulated knowledge and experience.

And finally, workshops are one part of our income. We don’t have any other jobs on the side, and exhibitions and commissions are not regular and do not always pay well, and yet the bills keep coming in. Hence, workshops help us to pay our bills.

FL: One of your works which most fascinate me is “Sonima” (2010). It’s a project that takes in account questions that have become quite recurrent in last months, mostly linked to Anthropocene discussions. The soft coexistence of technology and nature which is organic and artifical. Which is one of the main topics of your research: why are you so interested in this question? It looks like you’re trying to develop experiments for an utopistic future in which humans and nature live in symbiosis. Am I wrong?

V&M: Yes, many of our works express our futuristic thoughts or imagination where the digital age will lead us and our planet to. It is nice that you have noticed this. I would say this kind of concept in 2010 was quite subconscious. I (Varvara) was very interested in organic form but with mutational origins but still adapted by nature.

More conscious approach towards anthropocene epoch can be seen and felt in “Tree of Hands” (2015), which is one of our recent works. However, it looks like we have touched quite a taboo topic. For instance, “Tree of Hands” was rejected by jury of PAD London fair because of its depressive concept.

FL: “Shopping in 1 Minute” (2011) is another project I would like to ask you about. This work is about consumerism at its finest (or worst), turning one of the most typical capitalistic places (supermarkets) into ludic spaces. It’s a piece of social art that presents itself without informing the public what is right and what is wrong, but it rather suggests in a more subtle way the perversion at the base of that system. What do you think?

V&M: Yes. What we are doing is the absurd exaggeration of the same action (buying) to a maximum with one but: not buying and playing instead. There is a saying that shopping is 5 min happiness. The artwork tries to create a synthetic feeling of satisfaction of the ability to buy. The shopping centers are doing everything to stimulate our consumption needs, and our artwork manages to get inside their ecosystem and playfully releases that artificial desire to buy.

FL: With at least a couple of projects, you’ve also worked to the redefine hurban landscapes by looking at the invisble while at the same time taking on rather specific forces such as mass use of Wi-Fi networks becoming part of the everyday. I can’t help thinking that this is somehow related to privacy questions, probably because one of the most notorious scandals some years ago was Google’s secret recording of Wi-Fi networks with their Street View cars. Am I wrong?

V&M: Not really. But definitely Google has played a role in feeing our concerns about being watched, spied, hacked, scanned, etc. For example, the last scan for WiFi router names we did last summer in Tallinn some people were quite freaked out seeing a person on a bike with a camera on its head and tablet in front. I was even once asked if I worked for Google. 🙂 Anyways, the project was great fun for us, and we got to explore the city and discover the whole invisible communications networks and the self expressive layers of it all. After the Tallinn scan we even changed our minds about the 32-character local Twitter that the WiFi router SSID could be used for. The Tallinn experience showed us the new tendency: where people would use radio waves for semi-anonymous graffiti, communicating sometimes silly, protective, racist or political messages.

Talking about inspiration for this project, we got our interest for WiFi names from one article talking about the ability to track down pro- and contra-Obama communities by just looking at WiFi names in the neighborhood. This was before the US president election. Then we started to thinking of an art project on this topic.

FL: “The Rythm of City” (2011) is another project which is also ‘subtly’ related to control issues. The idea that someone can depict the state of a city by looking at data deducted from social media and web platforms. This type of thing is real now isn’t it – what do you think?

V&M: Definitely it is. However, the work’s main intention is not to talk about control issues rather about big data and its applications. Perhaps the main intention of this work is to offer to the viewer(s) a birds eye view on different cities in real time. In other words, The Rhythm of City allows you to zoom out and witness the larger picture on the current situation. And this larger picture is formed by everybody’s activity on social media, which is tracked down every minute. We call this action ‘unaware participation’ by digital inhabitants. The urban studies of Bornstein & Bornstein from early 1970s served as an inspiration for this artwork. They had discovered a positive correlation between the walking speed of pedestrians and the size of a city. Simply put: the bigger a city, the faster people move. The artwork demonstrates our interpretation of a city’s tempo through in its digital form or life. Hence, The artwork talks about pace of life in different cities at the same moment when the piece is viewed.

FL: What have you been working on these last few months and what plans do you have for 2016?

V&M: We are working on a series of new works talking about money. When we have completed “Wishing Wall” in London in 2014, since then we have noticed that the majority of people, especially a younger audience, wish for money. This really caught our attention. The ongoing hard economical situation in Europe pushes forward the need for money and also introduces a growing gap between the economical classes. So we’re investigating people’s desire for money and its connection with happiness. Making use of interactive technology we are aiming to approach playfully and magically the desire for becoming rich. At the same time, we cannot let go of knitting. At present, we are working on an open source flat knitting machine, which will be able to knit patterns also. Besides the new productions, we are showing our existing works in various exhibitions. For the confirmed ones, “The Rhythm of City” will be part of “REAL-TIME” a group show curated by Pau Waelder in Santa Monica museum in Barcelona from the 28th January. In February “Digital Revolution” (the touring exhibition by Barbican), which “Wishing Wall” is part of, moves from Onassis Cultural Center in Athens to Zorlu Center in Istanbul. And hopefully we get couple of other shows and new productions that are in the air at the moment and still to be confirmed soon.

Featured image: XRay by Claude Chuzel

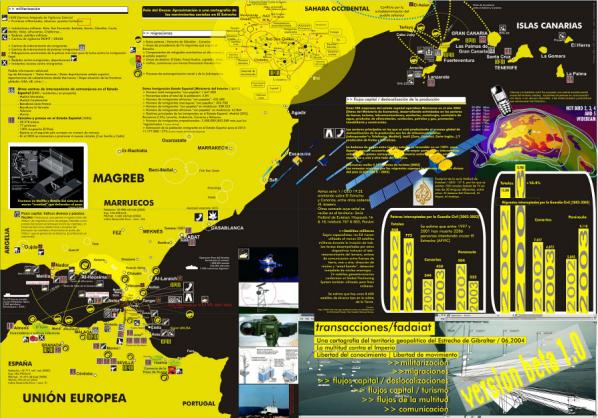

“One of the most consequential outcomes of this ubiquitous mode of organization of social life is that we have become so accustomed to relating to space in “either/or” and “here/there” terms that we have become mentally trapped inside this binary border-based model, making it difficult to imagine alternative ways of territorial organization.” Popescu [1a]

Maps inform us where things are situated. The borders depicted in each map propose a different view on the social conditions, attitudes, and interactions with others in the world. The AntiAtlas of borders project shows us different approaches for understanding “the mutations of control systems along land, sea, air and virtual states” and their borders. It has done this through the combined contributions of social and ‘hard’ science researchers and artists, all engaged in creative practices including Internet art, tactical geography, filmmakers, performers and hackers. The project also includes other relevant actors such as people working as professionals for customs agencies, surveillance industries and the military.

This is the first of two interviews with Isabelle Arvers who has collaborated with the IMERA team (the Mediterranean Institute for Advanced Research of Aix-Marseille University), to curate this expansive and dynamic project. The first interview discusses the operational side of the project and the next interview examines selected writings, artworks, projects and ideas featured as part of the project.

Marc Garrett: Before we begin the interview it would great if you could tell us when and where the exhibitions, events, publications and other parts of the project begin?

Isabelle Arvers: The AntiAtlas programme will run from 30 September 2013 to 1 March 2014 and will be composed of five initiatives: an inaugural international symposium, two exhibitions, a website and the publication of a book. The International Conference will be held from 30 September – 2 October 2013 at the New Conservatory of Aix en Provence. The main aim of this conference is to present the results of the interdisciplinary workshops that took place in the last two years at IMéRA et at the Higher School of Art of Aix-en-Provence.

The AntiAtlas of borders will present two interlinked exhibitions. The first will take place in Aix-en-Provence at the Musée des Tapisseries from 1 October to 3 November 2013. The second will take place in Marseille at La Compagnie creative arts centre from 13 December 2013 to 1 March 2014. The two exhibitions will present works developed in collaboration with social scientists, researchers in the hard sciences and artists. They will offer several levels of reading and forms of participation. Visitors will discover new works, engage with transmedia documentation and participate in experiments. They will interact directly with robots, drones, video games, walls and systems. The aim is to encourage everyone to reflect on how we are directly and personally affected by the transformations of borders in the 21st century.

The final version of the website www.antiatlas.net/eng is an online extension of the exhibitions. Most importantly, the website provides access to works of net.art and artistic interventions in the form of an online gallery of works. This website and its documentation will extend the progress and reach achieved by the project. It will act as an archive and documentation site for the general public, artists, researchers and institutions.

In 2014, an AntiAtlas of border publication will be produced, gathering publications of researchers and artists on different and selected themes of the international conference and the two exhibitions.

MG: What has been your involvement with AntiAtlas?

IA: When I met the IMERA team (the Mediterranean Institute for Advanced Research of Aix-Marseille University), they were looking for a curator in order to disseminate the outcomes of the past three years of seminars they conducted on borders. I saw this project as a great opportunity as there was a political dimension within it that attracted me. Also, I am deeply interested in tactical media and tactical geography and by new forms of visualisation and new aesthetics related to systems of control like drones, robots, satellites or surveillance cameras.

I wanted to create a participatory event that would allow people to follow our work online and offline. I also wanted to mix different kinds of works from research in the hard and social sciences to artistic installations, websites, games and videos. To do so, we decided to create a website www.antiatlas.net that would gather artworks, research articles and interviews, an online gallery and also all the presentations given during the different seminars conducted by IMERA on borders during the last three years. Thanks to the website, we were able to launch a call for proposals as I wanted to get the testimonies and the voice of migrants about their vision on borders.

Very quickly we understood that we needed to get more funding and partners, so I offered to seek media, private and institutional partnerships as well as to manage the communication of the entire event. This fundraising was needed to promote a global vision of the antiAtlas of borders and to link all the parts of the event: from the website, to the call for proposal, till the international seminar and the two exhibitions. Because of my multiple engagements in the project, I became one of the 5 co-producers of the programme.

MG: This is a complex project. It is noticeable that there is a diverse and dynamic, cross section of different practices being bridged to make it all happen. Has it been difficult to combine all of these practices so they can relate to each other coherently?

IS: Combining all these different practices was a wonderful and exciting adventure. During one year and a half, we worked very closely with the scientific and artistic committee and tried to exchange as much as possible between different visions and ways of working. I learned a lot from researchers and was amazed by the deep understanding and knowledge they have on the subject of borders. Thanks to their research and to their approaches to this issue, I was able to get a very diverse understanding of this complex subject. From me, they discovered the online communication and the power of the web and social networks to diffuse and share the information. They also got a better understanding of the tactical media field and we learned so much from each other that this experience is already a beautiful success in sharing and learning from passionate human beings. I come from media art world and I tried to respond to a scenario that the committee conceived with artists’ works, which is a very different way for me to work. This time I had a script to follow; the way I did it was to try to find some ludic interactive installations, as well as documentary projects or games, in order to allow the experimentation of the subject by the audience. They trusted me even if it wasn’t a field they knew well.

MG: Do you feel that it has de-compartmentalised these varied fields of knowledge successfully?

IS: What was particularly positive in the last seminars on borders we organised was that they allowed plenty of time to discuss and facilitate the exchange between the different perspectives. A specific example is a game project resulting from the collaboration between an anthropologist – Cédric Parizot – and a interactive laboratory from the Superior art School of Aix-en-Provence, which is led by the artist and game designer Douglas Edric Stanley. The idea is to create a “crossing industry game” drawing on the data collected by Cédric Parizot on trafficking. The collaboration addressed the visualisation, contextualisation and re-appropriation of a field of knowledge through game mechanics. I think that this experience really enriched all the team. The anthropologist was able to analyse his data in a different way, while the interactive students got closer to the reality of trafficking as they were experiencing through a game.

There are many other cross-disciplinary projects made in the framework of the AntiAtlas. I would say that what we want is to multiply different experiences and forms of knowledge on borders across and between the separate but intersecting fields of art and science. The exhibition is conceived to mix everything: research through the documentation space, researchers’ interviews, counter cartographies, interactive installations on biometrics and surveillance technologies, applications to divert control systems and documentaries providing a wider point of view on multiple dimensions of borders and their representations. Artists and researchers meet three times per year, some of them collaborate on trans-disciplinary projects, so that the conditions to meet and de-compartmentalise these fields are created. This is only the beginning. The process still needs to be pushed and facilitated as the antiAtlas is an attempt to create a new kind of cross-disciplinary encounter, let’s see how it will evolve!

This first interview with Arvers attended to organisational and operational aspects of the inter-disciplinary border-crossing within AntiAtlas project. The complex task of collating, sharing and collaborating to make it all happen at all could use its own map. The processes and engagements that evolved as the project took shape involved a collaboration of many different fields and practices, individuals, groups, organisations and cross cultural relations. This transdisciplinary approach helps us to unpack the deep levels of the meanings and value of crossing borders, in an organisational sense. Their dedication to transcend the seemingly ‘scripted’ blockages and restraints echoes a strong feeling that we need to re-assess the maps given to us, and what this means.

“What is needed to escape the modern mental “territorial trap” are ways of seeing and drawing that reveal what the geographical abstraction of the borderline obscures. It is only in this way, then, that we will acquire the necessary tools to think through a technologically enabled world of border flows and portals” Popescu.[1b]

Isabelle Arvers is an independent author, critic and exhibition curator. She specializes in the immaterial, bringing together art, video games, Internet and new forms of images by using networks and digital imagery. She has organized a large number of exhibitions in France and overseas (Australia, Canada, Brazil, Norway, Italy, Germany) and collaborates regularly with the Centre Pompidou and French and international festivals. http://www.isabellearvers.com/

Roger Malina is a physicist and astronomer, Executive Editor of Leonardo Publications (The M.I.T. Press), and Distinguished Chair of Arts and Technology at the University of Texas at Dallas. Dr. Malina helped found IMéRA (Institut méditerranéen de recherches avancées), a Marseille-based institution nurturing collaboration between the arts and sciences.

Mariateresa Sartori and Bryan Connell are two artists recently based at IMéRA. Their work connects with human movement through the city, and addresses the intersection between technology and perception. Recent work by Venice-based Mariateresa Sartori has encompassed drawing and video. Bryan Connell, Exhibit/Project Developer at San Francisco’s Exploratorium, works especially with landscape observation devices and mapping.

Lawrence Bird interviewed Roger Malina, Mariateresa Sartori, and Bryan Connell about the intersection of their work with the city. Images above courtesy: Roger Malina, Rita Gambardella, Bryan Connell.

Lawrence Bird: Roger Malina, in your recent writing you make the case that science is no longer just a field of positive knowledge. Scientists are increasingly open to engagement with the arts — for example artists’ residencies at CERN. You’ve even argued that we’re in a crisis of representation as profound as that of the Renaissance or the 19th century, and this is “driving a new theatricalisation of science.”

Urban life has often been understood as performative – display, performance of social roles, presentation of oneself before others are all part of the public life in cities. How would you say that crisis of representation plays out with regards to this performative dimension of urban life? How is science implicated alongside art in the city, in these conditions?

Roger Malina: One of my arguments for the ‘crisis of representation’ really looks at Renaissance systems of representation — first driven by what the eye could see, and then the eye extended by microscopes and telescopes. These systems of representation were developed that led to a deep contextualising of the viewer in the world.

Today we are in a new situation because so much of our perception of the world comes not through extended senses but, in a real way, through new senses. This has been happening over a number of decades; the first wave of this was at the end of the 19th century when there was a cultural shock with the introduction of x-ray images, infra-red and later radio — which didn’t extend existing senses but augmented them.The most recent series of triggers maybe comes from the nano-sciences and synthetic biology — we now perceive phenomena of which we have no daily experience of (eg quantum phenomena). Field emission microsopy or MRI or some of the other new forms of imaging really don’t build on our existing experience — there are discontinuities and dislocations. Another element is of course the hand held device that leads to techniques for ‘augmented reality’ — I have a phone app that I can point at an aeroplane overhead and it tells me what the plane is, where it came from, and where it is going.

Coming to your question about the city — there is clearly a shift in map construction and reading — from the Cartesian map that we have been acculturated to. The ability to toggle between the bird’s eye view and the “street view”, and the ability to view maps that have multiple layers simultaneously are driving artists and others to develop new forms of representation.

Someone whose work is interesting in this regard is Bryan Connell in San Francisco, he just finished an art science residency at IMéRA in Marseille. He was working on a large urban trail project called GR13 — 300 miles through industrial, urban, sub urban, and wild landscapes (the city had a hell of a time getting right of way through these areas). Bryan is currently working on a web site for the Marseille European City of Culture events, where he’s working on some of these questions of representation. The project involves a collective of ‘artist-walkers’ that I think fits right into this question of performativity.

LB: There’s currently a great deal of interest in the connections between representation, digital technology, and politics, for example the current Hybrid City II conference in Athens. As you’ve pointed out, these often underline the connections between what digital media mean for artists and what they can contribute to citizens — what’s emancipatory about them. What can art offer civil life in this context? Are there any conflicts or contradictions in that relationship?

RM: One pertinent example is the work of Bruno Giorgini, a physicist, and Mariateresa Sartori (visual artist) who work on the “physics of the city.” They were recently in residence in the IMéRA Mediterranean Institute of Advanced Study which hosts artists and scientists in residence who want to work with each other. We now have access to incredible amounts of data on human mobility (pedestrian and various forms of transportation) so it is now possible to study human behaviour quantitatively. Sartori discovered that she could tell many things about a person just through the morphology or topology of their movements through the city. Girogini discovered that people’s movements could be predicted at the 80% level, but 20% of the time he had to introduce what he called ‘social temperature’; in discussions he also referred to this as a ‘free will’ parameter. Barabasi has found similar results analysing cell phone GPS data of individuals. So its interesting to think of the development of cities as 80% predictable and 20% serendipitous. This of course then highlights the role of the arts and culture in making cities part of the cultural imaginary that drives people to make choices. Recently Max Schich here at the University of Texas has analysed very large data bases looking at where prominent people are born and where they die over the last 500 years. Immediately you can see how suddenly certain cities become cultural ‘attractors,’ say the way Berlin or Hong Kong are now. And of course cities are now trying to ‘design’ this into the development of cities. Here in Dallas there has been a huge investment in the ‘arts district’ and in institutions of higher learning in the belief that healthy cities require such investments. See for instance the US National Endowment for the Arts Program; there are many similar programs in Europe.

This doesn’t yet address your ’emancipation’ question. One of the things that is happening is that we are becoming a data taking culture (see the recent literature on ‘big data”). The cell phone has transformed every citizen (that has one) into a data taker. Of course much of this data is used by companies for marketing objectives. But many citizen groups are now able to take data for their social objectives. Some of this is captured by the ‘citizen science’ movement ( one example is here). There have been good examples of citizen’s taking data (on pollution, on illegal activities etc.) and then being in a position to challenge ‘authorities’ of various kinds whether scientific, political or economic (see for instance the way citizen groups have mobilised to collect data after man-made disasters such as oil spills, or illegal logging in forests).

A few years ago I wrote an open data manifesto which argued that I would like to advance a new human right and a human obligation:

1. Each of us has the right to the data that has been collected about ourselves and our own environment.

2. Each of must contribute to the knowledge construction by collecting and interpreting data about our own world.

Most scientific data collection is funded by public tax payer funding. The public has a fundamental right to all data collected and funded by public tax money.

LB: How do you imagine an artist’s training will change as these conditions evolve? And a scientist’s — could we foresee any kind of convergence?

RM: One interesting development is a cohort of hybrids, who have one degree in science or engineering and one in art and design ( for example J.F. Lapointe, a researcher at the National Research Council of Canada with degrees in molecular biology and dance) or degrees in Science or engineering and employment in art or design (like myself or Paul Fishwick, a key figure in the field of aesthetic computing). There’s been an emergence of art/science Ph. D. programs that take students from art or design or science or engineering. I suspect this cohort will grow over the coming years.

LB: Mariateresa Sartori, your IMéRA research project with Bruno Giorgini focused on mobility in the city. Can you tell us a little bit about how your work and Dr. Giorgini’s work complemented each other? What kind of evidence did you bring to the table as an artist?

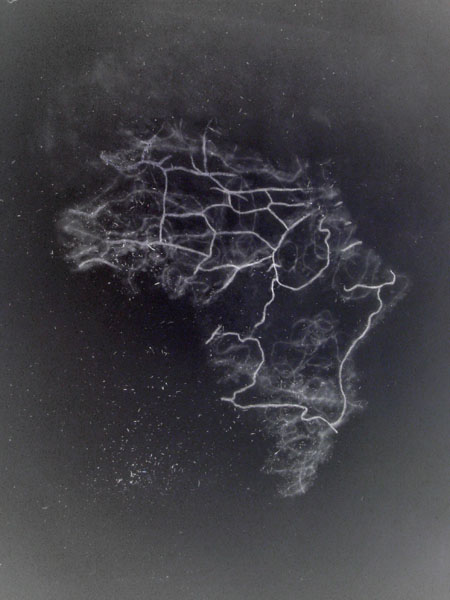

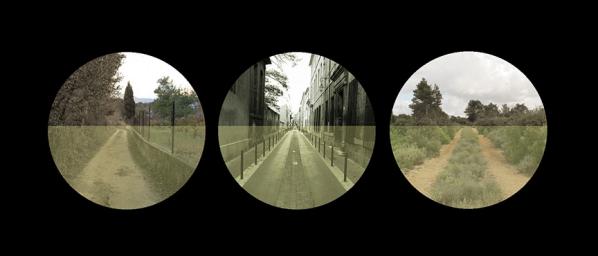

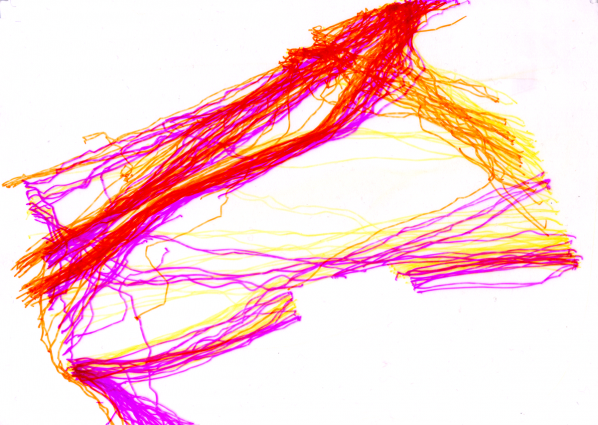

MS: The project I worked on with Bruno Giorgini developed an exploration that began with earlier work in Venice. There I created a series of drawings using a rudimentary, even crude procedure: I traced out the movements of each pedestrian in the Piazza San Marco, drawing their paths with a felt-tipped pen on a transparent sheet placed over the computer monitor. I then faithfully transferred the results onto ordinary large sheets of white paper. The lines thus drawn in different directions created a space, drawing a St. Mark’s Square that is actually not there. As well as the actual physical space, it is also a drawing of our individual and collective manner of relating to space. Each single path determines the route of others, in a continuous and reciprocal game of influences that makes our collective progress.

At IMERA we developed this method for a new environment, a city more ethnically and culturally plural than Venice. Together we set up procedures and tools for collecting data about mobility networks there: nodes, links, chronotopi. These drew on the work of Bruno Giogini’s Laboratorio di Fisica della Città of the University of Bologna. We shot videos focusing on specific behavioural patterns where strategies of shifting, approaching and distancing play a decisive role; and we were also attracted by the places and situations of pedestrian congestion. Using the same technique as in Venice, I translated these into drawings of movement. These again created a space that marks out squares and places which are actually not there, each synthesizing space, time and humanity in a single image.

LB: Is there an emancipatory or governance-related dimension to this work? Degrees of mobility have human rights implications. How does your work as an artist connect with these rights, especially the notion of the right to the city?

MS: The first goal when I work as an artist observing reality is observation, i.e. a way of observing that implies a new attention. The result is always instructive because I do not have particular expectations. After lines have been traced following my process, something always emerges and what emerges can be a useful and indicative element for the emancipatory dimension of the urban condition. I would say that Bruno Giorgini is more involved in that dimension than me, especially in the notion of the right to the city.

LB: There’s a current preoccupation among researchers in a number of fields with the relationship between representation, often engaged with/through technology, and urban life. How has your latest work connected with this relationship?

MS: My way of working with technological instruments such as computers is very particular and limited. I use the computer as a technical tool strongly mediated by the senses, i.e. by human perception. I am very interested in modalities of perception: they are so imperfect, yet sufficiently perfect to make our existence possible.

LB: You described the way you work with technological instruments as “particular and limited.” Another way to look at this is that you make the technological system slow down by inserting yourself into the process… and the result is your drawings, which still movement. Might this be one role for art — to insert the human into the machine? Much net art focuses on flows of information, virtual movement, and representing that. While not quite glitch art, do your representations of movement in some sense intentionally put a brake on the machinery?

MS: I find your words enlightening, you describe my way of working better than me….. Actually I insert myself into the technological process…..but this is not a statement of a position against technology.

I can say that what interests me the most (and art’s relation to science is just one instance of this) is the thread of connection between specific cases and general theory, between subjective and objective. Between, on the one hand, the singularity of events and, on the other, general theory. The individual’s experience is singular, unique; but there is always a thread, even if fine, that leads each individual case to a wider generalisation. What interests me is this incessant – indispensable as much as concealed – mental activity that every day leads us to search for generalisations and regulating principles. What interests me is the human tendency to comprehend phenomena, even the most complex, via schematic representation, via a generalisation that leads to the identification of organising principles. I mean “Comprehension” in very wide sense, where emotions and feelings participate too in embracing reality, including reality. Maybe in this sense I put the human in the machine…

There is a discrepancy between how we perceive reality, mediated by our senses, and the truth decreed by science. On a rational level we recognize the truth, but we cannot internalize in a deep way this knowledge; this is beyond our human capabilities. I think that in my artistic research I find myself in this deep discrepancy.

LB: Bryan Connell, your work in Marseille addresses, among other concerns, technology and its relationship to nature. Do you see the urban environment as playing any particular role in that relationship — of having a particular status in our negotiation of it?

Bryan Connell: One of the things that intrigued me about the metropolitan hiking trail in Marseille is the way it plays with our sense of meaning and value in the exploration of contemporary landscapes. Most long distance hiking trails are designed to lead out of urban environments, not into them. We don’t usually think of carrying a field guide that illustrates the taxonomy of fire hydrants, electrical pylons, or urban weeds on an extended city or suburban walk. That kind of engaged, systematic attention is usually reserved for wild natural terrains. From a traditional environmental perspective, the less altered a place is by human technology, the more scientifically interesting, ecologically exemplary, and aesthetically rich it’s going to be. Without undermining the validity of ever-present environmental concerns, the trail functions as an invitation into a more challenging and complex relationship to the emerging para-wilds and novel ecosystems that are arising at the intersection of the natural world and the technological infrastructure of the built environment.

Similarly, the Marseille trail doesn’t really focus on the kinds of urban sites that are traditionally thought of as having significant historic, architectural, or cultural interest. Instead, the trail route incites visitors into an exploration of the everyday environments and working landscapes of the contemporary urban transect – a world of parking lots, freeway overpasses, suburban developments, abandoned railways, and semi-rural wildlands.

Landscape ecologist Earl Ellis argues that to better navigate our way through the current geohistorical epoch, the Anthropocence, we must expand the traditional ecological concept of regional biomes into the parallel notion of “anthromes” – biomes that are complex interconnected melds of human technology and natural systems. In a sense, the GR 2013 Marseille trail is a sketch or system of exploratory paths into what a publically accessible, anthrome based urban ecology observatory might look like.

LB: A similar question is in relation to the image, especially sequential images. What does it mean for our negotiation of the relationship between nature and technology? Between science and art?

BC: We increasingly live in a networked digital metropolis with an image and information density that both mirrors and exceeds the high population densities of the physical metropolis. One topic of particular interest to me is the role these images play in transfiguring the quality of our desire. To what extent do scientific or aesthetic images that increase our ability to find meaning and satisfaction in observing and understanding urban landscape phenomena mitigate our need to physically alter the landscape to conform to an idealized image of what it should or shouldn’t be?

For example, the Marseille metropolitan trail didn’t require much physical alteration of the terrain – it’s a conceptually designated network of pre-existing roads, paths, streets and highways. The trail’s function is not to alter place, but alter the cognitive landscape of trail users so they have a richer sense of place. If you are fascinated by the diversity of ways a para-wild plant population has adapted to a technologically modified environment, do you need to engage in an energy and material intensive re-landscaping of that environment with a palette of conventional horticultural plantings to make it more “beautiful”? In this sense, constructing interpretive images of landscape is more than a way of augmenting a recreational hiking experience, it’s a way of shifting and re-configuring what we think we have to consume and alter to find meaning and vitality in contemporary landscapes.

http://uranus.media.uoa.gr/hc2/

Hybrid City is an international biennial event dedicated to exploring the emergent character of the city and the potential transformative shift of the urban condition, as a result of ongoing developments in information and communication technologies (ICTs) and of their integration in the urban physical context. After the successful homonymous symposium in 2011, the second edition of Hybrid City has grown into a peer reviewed conference, aiming to promote dialogue and knowledge exchange among experts drawn from academia, as well as artists, designers, researchers, advocates, stakeholders and decision makers, actively involved in addressing questions on the nature of the technologically mediated urban activity and experience.

The Hybrid City 2013 events also include an online exhibition and workshops, relevant to the theme

Hybrid City Conference 2013: Subtle rEvolutions will take place on 23-25 of May 2013.

The Hybrid City II events will take place at the central building of the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens.

This document was edited with the instant web content composer. Use the online HTML editor tools to convert the documents for your website.

Sign up: ale[at]furtherfield.org

See images of the walk on Flickr.

Public exploratory radiation walk around Finsbury Park, measuring mobile phone radiation levels and discovering what type of radiations we are exposed to on a daily basis. As we walk, we will unravel a parallel, hidden story of the local area along with technical data and possible medical effects of the radiation. Participants will measure radiation levels, GPS positions and marked levels on a large map of the area, creating a collaborative artwork (poster sized map of local radiation) to be made available for display as part of the exhibition after the event.

Participants are encouraged to listen to the sounds we will be hunting for (GSM, 3G, Tetra) here.

Dave Miller

Dave Miller is a South London based artist and currently a Research Fellow in Augmented Reality at the University of Bedfordshire. Through his art practice Dave draws out the invisible forces that make life difficult. His work is about caring and being angry, as an artist. His art enables him to express feelings about the world, to attempt to explain things in a meaningful, yet subjective way, and make complexed information accessible. Recurrent themes in his work are: human stories, injustices, contentious issues and campaigning. Recently he’s been very bothered by the financial crisis.

+ Finsbury Park Radiation Walk is part of Invisible Forces at Furtherfield Gallery.

+ More Invisible Forces events.