Dave Young writes within the context of Localhost: RWX, a symposium and worksession at Edinburgh Sculpture Workshop from 29-31 October 2015. For more information about RWX, visit the Localhost website. RWX is funded by Creative Scotland, with support from New Media Scotland, Furtherfield, and Edinburgh Sculpture Workshop.

As smart devices shape the near future of personal computing, we – as users – are experiencing a shift in the way digital data is represented and accessed. For the last five years, Apple, Google and the other tech giants have desperately attempted to position themselves as market innovators and patent holders in the next generation of consumer tech. Over this period, we have seen more companies dropping desktop PC production in favour of novel gadgets such as smart phones, tablets, watches, fitness bands – and even contact lenses, glasses, and so on. A noticeable side-effect of this shift is that the ‘traditional’ filesystem interface, familiar to us as a visually traversable hierarchical structure of files and folders, is replaced by an app-centric interface. With its primary objective of being more user-friendly, this kind of interface limits as much as possible the tedious and touchscreen-hostile tasks of file management and directory navigation. It’s certainly worth reviewing how data should be represented in the modern Operating System – “tradition” is not enough reason to purposefully stick to an old system of files/folders, created by Xerox for their Alto/Star OS in the 1970s. That said, any radical change in the interface design of the filesystem needs to be critiqued, as it is acts as the mediator between us, our data, and our tools.

It’s worth emphasising that the aforementioned Xerox system is also a metaphor – it does not necessarily offer us a truer insight into the raw data on our devices than an app would. In the case of wanting to open a .txt file, whether we do this by selecting files via OSX’s Finder/Windows Explorer/one of the myriad File Managers in the world of Linux, or by opening an app on a “smart OS” such as iOS/Windows Phone/Android, we still achieve the same end goal: while the rudiments of the interface might change from one system to another, the .txt file is still utimately accessed and displayed to the screen. But between the traditional Xerox system and newer mobile interfaces, there is an interesting divergence. In the former instance, we navigate to the information, the precise location of the particular file /within/the/hierarchy/of/directories, then choose to open it with a tool of our selection. In the latter case, we select the tool, which then prescribes what information can be accessed with it. This simple inversion of intent does fundamentally alter our experience of the filesystem, but what’s at stake when we prioritise the choice of tool over the choice of file?

In the case of the former interface, we are provided with a visual map of our data. We can see where something is stored, how it relates to the other data we have saved, and also its related metadata. We are presented with an open scope, an indexical view of the files stored in our device’s memory. By default, we have the option of surveying data saved to our hard drive, and we can choose to ‘explore’ this should we so desire.

In the case of the typical smart OS interface, where the selection of a tool is prioritised over the selection of a given file, our vision of the filesystem is closed down by a “helpful” framework that only displays data that can be opened with a particular app. The messages app allows you to read your messages, the note-taking app allows you to speedily write notes, yet ne’er the twain shall meet – unless through a closed black-box framework, often labelled as ‘share’, which again guides you to an app that mediates your selection of file. As if peering through a keyhole, the user sees their filesystem in discreet parts and at particular moments, mediated by a given app’s functionality and filetype preferences.

It must also be said that, increasingly, much in-app data is often not even locally hosted on the device. It occupys no discernible, indexed space on its hard disk – at least no space that is visible and open to the user. Instead, it sits in a dynamic, transient “app cache”, where information is stored temporarily, to be frequently written, updated, and wiped without the user’s explicit knowledge or conscious intervention.

But this problem has a simple solution: why not just download a file manager from an app store?! It is of course an easy task to download a third-party file manager, but why was the filesystem manager done away with in the first place? Default configurations are rarely inert gestures. The omission of a stock file manager should be understood as a deliberate design decision intended to influence or shape the way we engage with the device. Is its omission, for instance, a desire to shake up what is seen as an antiquated interface? Is it a victim of contemporary design obsession about UI friction and clutter?

Searching for a file in a directory tree and not being able to find it can be seen as an example of friction. It is a moment where the ‘user’ becomes aware that they are ‘using’, activated by frustration or self-reflexive concentration and the necessity to make decisions, to search, to solve a problem. Finding the lost file is a terribly banale puzzle, but one that at least self-conciously engages the user. The app interface, which always tries to guess what you want to do next under its chief design objective of smooth simplicity, aims to remove friction. The smart OS is not free from friction though: when it guesses wrong, a manual solution can be more complex to rectify than the traditional filesystem interface, and perhaps at this point, the user realises they may not be as free to ‘use’ their technology as they expect.

Recently, we can see how some features of the smart OS are invading the desktop Windows, Mac and (to a lesser extent) Linux Operating Systems. Ubuntu, the most popular desktop Linux OS, raised controversy when its new Unity interface was unveiled in 2012, with a noticeably touch-friendly design aesthetic featuring large app tiles and fancy but pointless UI features. Was this part of the wider trend as demonstrated by Apple and Windows, where an ecosystem of multiple devices share smart and responsive interfaces, homogenous no matter the screen size, format, or method of interaction? Since then, Canonical (the parent company that develops Ubuntu) have attempted to venture into the smartphone market, working on both software and hardware, with an OS that neatly ties into the Ubuntu desktop experience. This approach to smart OS design is not simply a matter of convenience for the user, but good business sense too, especially as it becomes increasingly common for a technically adept individual to have a computer at home, a tablet in their bag, a phone in their pocket and a smartwatch on their wrist. Interface and brand go hand in hand: a suite of devices that play nicely together, share files conveniently over fancy wireless protocols, and look good when sitting side-by-side on a coffee table further encourages brand loyalty.

Despite its somewhat unforgiving text-based interface, it is the Terminal that perhaps offers the least mediation of all filesystem interfaces. Commands are taken as commands, presumed to be intentional and subsequently applied, whatever the consequences. When developed according to the UNIX philosophy of “do one thing and do it well”, command-line tools have the ability to “pipe” a standard output to an input of another tool – that is, each tool can share its output with the input of the next tool. Tools and files are thus recombinant, and in their purest form, are not hidden from one another. A basic example, featuring an ASCII cow:

ls -a #lists all files in the current directory.

. .. My_Computer.gif .shhh_super-secret.file

ls -a | cowsay #the standard output of 'ls -a' is piped into the standard input of cowsay. Hence, an ASCII cow lists out files for us.

_____

< . .. My_Computer.gif .shhh_super-secret.file>

-----

\ ^__^

\ (oo)\_______

(__)\ )\/\

||----w |

|| ||

Or for example, the ‘cat’ command dumps the contents of any file into the terminal. It does not really matter what you try to ‘cat’ – it could be an image, or whatever is in the RAM of your computer – if you have Read permission it will duly carry out your command.

cat My_Computer.gif #prints file contents to standard output

GIF87a+#)#� ######�##�#�##�����#�#���#�����������������������,####+#)###�0�I��8�ͻ�`(��X�h���T#p,�GR#m#�8��@#��[#�7b�#h:�Ndϴ##���U�d##P+��~u#�v9,{ ��`.#��o#Zbg'�bM{ }#mxjp#��"?�ak�xG+~S�K#��;KAA<'&��#'L"a����#����#���#?��0(���������##4�MŹ#�##��3�#����#�I�8�68��#z�����<���7���)��-l��ڼ�#� ����C##*�###;

sudo cat /dev/mem #prints the contents of a device's Random Access Memory to standard output

Yet, despite its direct and explicit interpretation of user input , we must return to the fact that the command line is a simulation – or more appropriately, an emulation – of a interface that mediates our relationship with the digital information stored on disk. Its commands recursively refer to lower-level frameworks and architectures, until it reaches the level of bits and electrical pulses.

Ultimately, when we discuss these issues about interface and access to information , we come to much greater issues surrounding the essence of memory and access to knowledge itself. As with any indexical system of information management (whether we speak of the archive, the library, the museum, or indeed the filesystem), there are inherent biases in the structures of representation that mediate and inform how we relate to the information contained within. There is a strong history of theorists (Jacques Derrida’s writing in Archive Fever being the obvious one) who attack the politics of the archive and our habits of designing biased frameworks for the storage of memory – certainly useful in these times, when we shift from one interface whose biases are familiar to another whose biases still somewhat elusive and in flux .

In the present though, it has become increasingly clear that the interface bias of the smart OS prioritises data-access and content-delivery, focusing on consumption rather than production. Maybe a filesystem manager is surplus to requirement for many, yet the ommission of such a perspective on our filesystem creates some issues for us as users. The phenomenon of ‘black-boxing’ – whereby complex activity is cloaked and opaque, incomprehensible and impenetrable to the user – becomes normalised. As a consequence, we can’t easily understand the behaviour of an app and the data it produces/accesses, we can’t explore what logs exist on our devices, and what personal data is potentially exposed to typical threats such as viruses, malware, hacks, and thieves. The perspective we have is simplified, and in this case, to simplify is to remove options, alternatives, and user-agency. The use-possibilities of our devices are parametrised, governed, and constrained by the overarching system of app-centricity, while opportunities for subversive intervention and creative misuse are reduced as we are obliged to act and respond within the increasingly powerful context of app store regimes.

Those orphaned config files, scripts, metadata, caches, loggers and logs: they will continue to reside in our most obscure, exotic directories, unseen, but saved.

—-

Also Read

* Turing Complete User – Olia Lialina

* Preface to FLOSS+Art – Aymeric Mansoux and Marloes de Valk

* McKenzie Wark – A Hacker Manifesto

* The Interface Effect – Alexander Galloway

The first interview with Jake Harries, took place on one of Furtherfield’s Radio broadcasts on Resonance FM, earlier this March 2011. Fascinated by the historical context that came out of the radio discussion, we asked Jake for a second interview, this time it took place via email.

Jake Harries has been making music in Sheffield since the 1980s and is a sound artist, musician/producer, composer and field recordist with a strong interest in media art and the practical use of Open Source audio-visual software. He was a member of electronic funk band Chakk which is best known for building Sheffield’s first large recording studio, FON Studios, in the mid 1980s. He is currently one of “freestyle techno” trio Heights of Abraham and The Apt Gets, a band which uses guitars and only Open Source software on recycled computers to create songs from spam emails. He is Digital Arts Programme Manager at open access media lab, Access Space, and the current curator of the LOSS Linux Open Source Sound a website dedicated to music made with FLOSS.

Marc Garrett: Lets talk a bit about your own history first. You were in a band in the 80s called Chakk, could you tell us a bit about that?

Jake Harries: Chakk was based in Sheffield during the mid 80s and we are best known for building a heavily used facility, FON Studio, Sheffield’s first large commercial recording studio. Chakk made “industrial funk” music, a mix of funk base lines and drums with influences ranging from punk to soul to free jazz and electronica. Our music was aimed squarely at the dance floor. We believed that technology, in this case the recording studio, was the most important instrument a band could have both creatively and financially.

MG: So, you are part of the electro music history of Sheffield with bands like Cabaret Voltaire & The Human League in the late 70s – 80s?

JH: Yes, but the band itself didn’t have too much commercial success, a couple of indie chart top 10s and a couple of low 50s in the main UK chart, so few people remember us now. People are more likely to remember FON Studio.

Recently a documentary has been made, called The Beat Is Law, about Sheffield music at that time, so perhaps there will be a bit more interest in the band.

MG: Open Source software is freely downloadable from the Internet for free and Linux is the most widely used Open Source operating system. How long have you been using Linux operating systems and Open Source?

JH: I had heard of Linux before, of course, but I came across music applications which were developed only for Linux in 2002-3 while searching for new software tools. These intrigued me sufficiently to install the operating system on a pc which I had fixed where I was working at the time.

MG: Do you feel that artists, techies and others are choosing Free and Open Source resources for reasons which connect with ethical and environmental issues and concerns?

JH: Well, I’d like to integrate into this answer the general themes of openness and transparency. FLOSS is akin to an encyclopedia of how to make things in the software realm because all the code is available for anyone to download and develop; closed, proprietary software is like a “sealed box” which it is illegal to prise open.

But it goes a bit deeper than that: in the world we are living in now the “sealed box” is increasingly becoming the mode of choice for all kinds of products, most of which, because they are designed to be superseded, have built in obsolescence. When something goes wrong with a product, you are unable to fix it yourself because you can’t get inside it, and even if you could you can’t find out how to fix it. If it is out of warranty, either you pay a lot of money to get it fixed or you throw it away; then you buy a new one! (Which is what the market wants you to do…)

So, it feels very much as if we are surrounded by technology we are not encouraged to understand and products with a limited life span: the obvious environmental concern is, “what happens to my ‘sealed box’ when I throw it away?”

Using a Linux operating system can increase the useful life of a computer by several years, and perhaps, if you can hack into them, other products too. So it is great if both hardware and software are open.

We also know that sharing knowledge is generally considered to be a good thing as it allows people to build on what has already been discovered. Being able to give the people in workshops the software they have been learning to use because it is FLOSS, rather than them having to pay several hundred pounds because it is only available on a commercial license, is great and often the idea of this kind of freedom takes a while for people to get used to if they’ve not come across it before.

MG: Why is it important as a creative practitioner to be using Open Source?

JH: Well, personally, I have realised that what I’m interested in is freedom, not just as a hypothetical, but the practical reality, finding out how to achieve some of it and if it is possible to sustain it. Free & Open Source operating systems and software are one way of stepping out side of the constant pressures of the commercial market places which dominate our culture.

We tried this in Chakk in the 80s with FON Studio, attempting not only to personally own the means of producing our music, the studio (allowing us to be outside the corporate system of production), but also to be able to explore our creativity in the way we wanted to. In the case of Chakk it didn’t work out. We had, rather cheekily, persuaded a giant corporate (MCA Records, owned by Universal) to bank roll it all and they found ways of scuppering our plan by making our product conform to their idea of the market place: transforming it into something “radio friendly” and bland, taking the energy and urgency out of the music. We were quite a politicised band and that energy was essential to our musical integrity.

However, when MCA dropped us we had a recording studio which could help nurture new music without too much external pressure, and this led to records produced there by local acts fulfilling their potential and going into the charts.

I think it is important for artists to have certain freedoms, to have ownership over the means with which they create their work. The fact that FLOSS allows you the user the potential of customising the tools you use and to distribute them freely via the web or other means is quite profound. And one of the real benefits of using FLOSS as a creative practitioner are the use of open standards and formats.

MG: OK, let’s move onto your own band: The Apt Gets. Now, since The Human League & Cabaret Voltaire, a whole generation has experienced the arrival of the Internet. Your group seems to reflect this aspect of contemporary, networked culture – a kind of Open Source rock band. Could you tell us about this band The Apt Gets, how you all got started and why?

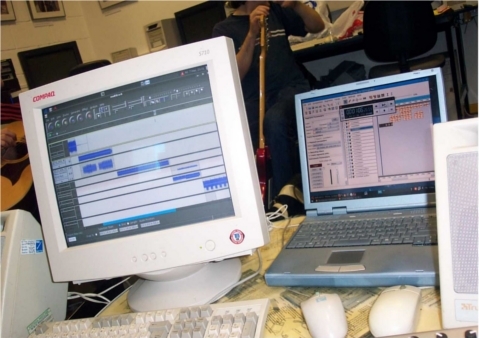

JH: It began with workshops I was leading for musicians on FLOSS audio tools in 2007. The idea of an “open source rock band” came up – at the time we didn’t think there was one so a couple of the workshoppers and myself formed one. The Internet was the main source of inspiration really: we used recycled computers with Linux we’d downloaded, as well as guitars and vocals. I’m interested in re-purposing junk as raw material for creative processes and decided to re-use some of my spam emails as lyrics. We all hate spam, but re-contextualising it like this is fun, as is introducing a song by saying, “Here’s a classic Nigerian email asking for your bank details”. The themes of spam emails are generally things like greed & money, status & sex appeal as well as “meds”, so there’s more to them than you might think.

MG: Now, I personally know why, but others who are not as familiar with Linux and Open Source Operating systems, will not immediately know this. The naming of your band’s name – it’s specific to installing software. Could you tell us more about that?

JH: On a Debian Linux based operating system one can install software from the internet using an application called apt. One could type apt-get install the-name-of-the-software into the command line and apt will get the software from what is called a repository on the Internet, where the software is stored for download. We thought that if you called someone an Apt Get it could be interpreted as an insult meaning something like, clever bastard. So, that’s why we named the band The Apt Gets.

MG: How long has your research project with FLOSS been going?

JH: The research project started in 2007. Ever since I began to use FLOSS I’ve been interested in the practical realities of using it, particularly as an every day set of tools, as an ordinary computer user would use it: for instance, when I do work on the arts programme at Access Space I don’t use anything else. So, it made sense to discover how a number of non-Linux using musicians would find using FLOSS audio tools – if I was being an advocate for FLOSS I ought to look at it from the new user’s angle and discover how far they could go and what kind of time scale they need.

MG: And the web site address is?

JH: http://audiotools.lowtech.org

MG: How easy is it for someone with little or no experience of Open Source software and Linux based operating systems to install it?

JH: It is quite easy nowadays. A Linux distribution like Ubuntu has an easy to follow installer which allows you to create a dual boot if you want it, that is, keeping your Windows system as well so you have the choice of both.

MG: At Access Space in Sheffield, you are curator and researcher of LOSS (Linux Open Source Sound) a website dedicated to music made with FLOSS – which is basically LOSS with the letter ‘F’ added, meaning ‘Free Linux Open Source Sound’ – FLOSS!

JH: Yeah! Free is the word! It is a repository for music made with FLOSS tools and released under a Creative Commons license. You can freely download and upload tracks. Initially it was based around two projects, a physical CD issued in 2006 curated by Ed Carter, and LOSS Livecode, a mini conference and gig curated by Alex McLean and Jim Prevett based around the international livecoding community. The website is at http://loss.access-space.org.

MG: What is Access Space and what is different about them as a group?

JH: Access Space is an open access media lab, based in central Sheffield. It uses reused and donated computer technology to provide Internet access and Open Source creative tools, free of charge, five days a week. It started in 2000 and has become the longest running free Internet project in the UK.

We recycle computers, put on art exhibitions, creative workshops and sonic art events. We’re currently developing a DIY Lab, modelled on MIT’s FabLab or fabrication laboratory. This will be an interface between the physical and digital domains where new kinds of creative activity can be developed.

MG: What operating systems would you suggest to newbies coming to Linux for the first time?

JH: Ubuntu or its derivative, Linux Mint, are both very user friendly for everyday use. For audio try Ubuntu Studio, 64 Studio or Pure:dyne.

MG: And regarding yourself, what are you using?

JH: I have set up eight Ubuntu Studio pcs for use in audio and video workshops at Access Space; and I use Pure:dyne live DVDs if I’m out and demonstrating on other people’s pcs. For everyday use, again Ubuntu Studio with a few additional applications like OpenOffice.

MG: Thank you for a fascinating conversation.

JH: It was a pleasure…

Open Access All Areas: an Interview with James Wallbank about Access Space by Charlotte Frost

http://www.metamute.org/en/Open-Access-All-Areas

Ubuntu Studio 11.04 release.

http://ubuntustudio.org/

64 Studio Ltd. produces bespoke GNU/Linux distributions which are compatible with official Debian and Ubuntu releases. http://www.64studio.com/

Puredyne is the USB-bootable GNU/Linux operating system for creative multimedia.

http://puredyne.org/

Pure:dyne Discussion, interview by Marc Garrett & Netbehaviour list Community 2008.

http://www.furtherfield.org/interviews/puredyne-discussion-netbehaviour