Featured image: Image from Fab Lab (fabrication laboratory), small-scale workshop offering digital fabrication

There is currently a significant amount of interest in the relationship between free and Open Source practices in art and the aim of this report is to map out some of these shifting relationships in contemporary models of education both online and offline. The recent expansion of so-called ‘free culture’ has contributed to placing the debate over authorship, ownership and licensing of the artwork at the centre of artistic production. Crucially, the transformation of art in the age of global culture and the consequent move from autonomous art objects into cultural artworks and services, has resulted in the emergence of three visible tendencies: 1) free/Open/Source software as artistic-pedagogical method, 2) the critical emancipation of the self-education movement and 3) the digitisation of art education practices into Open Source packages of cognitive labour.

One possible way to navigate this complex ideological terrain is the conciliatory term free/libre/Open Source software (floss), seeing it as “part of an emerging transdisciplinary field that deals with different forms of openness.” [1] At the heart of the debate is the political distinction between the Free Software Foundation[2] and the Open Source Initiative.[3] The ‘copyleft’ attitude (free software movement) asserts four freedoms for software: free from restriction, free to share and copy, free to learn and adapt, free to work with others.[4] The Open Source definition,[5] on the other hand, in spite of apparent similarities, has developed into flexible arrangements such as the Creative Commons licenses[vi][6], some of which restrict these freedoms when applied to media/cultural works and publications, not allowing for derivative artwork or its commercial use under specific license combinations.[7]

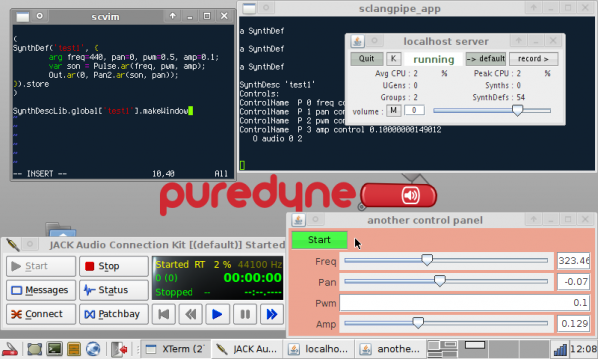

A number of projects, such as the pure:dyne[8] – GNU/Linux operating system for live audio visual processing and teaching – are, however, fully identified with the principles of free software. They have emerged from artists’ collectives whose relationship to art education is informally associated with sharing spaces, the hacklabs and free media labs where they run workshops and introduce participants to the use of free digital art tools. [9] Their mode of production is centred on ‘live code’ and feature two essential characteristics: 1) collaborative- relying on large-scale public participation and 2) distributive- offering the tools and the process notes (notation) to empower the others to carry on the work on their own.[10] This philosophy implies that the artistic performance of the work is complemented by a set of pedagogical approaches associated with the enabling of production by others. [11]

The movement for free education has gained greater relevance as a result of the global financial crisis and the battle for control of university fees.[12] In this context, art education has been developing into an artistic project while also providing an emancipatory movement reacting against dominant forms of institutionalised knowledge production. Within this movement, the role of free/open technology has been central in the mediation of self-education as a social movement.

On the one hand, artists –freelancers, sometimes temporarily/precariously plugged into educational institutions whilst working as teachers, others times as workshop facilitators in free access spaces– have opened up their classrooms to the environment of the read/write web, and with their students-collaborators, have produced and shared in wikis, blogs and Second Life, art and education resources that make an increasingly significant contribution to a larger body of knowledge that is the web. [13] Wikiversity is a model of this confluence of self-education movements and open online education.[14]

In parallel with the above-mentioned tendencies of online systems, numerous critical projects have appeared that are associated with the reclamation of space that occurs as artists have found themselves at the forefront of self-organised and self-managed self-education projects.[15] Some have happened side-by-side with the reclamation and occupation of spaces such as the Temporary School of Thought[16] and the Really Free School.[17] Part of these groups activity is the establishment of a free programme of workshops on topics that can range from free software tools to Ivan Illich and Deschooling Society.[18] Others that make opportunistic incursions into the artworld such as the Bruce High Quality Foundation University,[19] the Future Academy[20] or Unitednationsplaza,[21] are platforms for experimental art as research, investigating the production of knowledge that occurs when art education itself becomes artwork or exhibition.[22]

While the debate on free education has been enjoying significant visibility, the Higher Education sector has also joined in. A few recent initiatives have supported universities of the arts developing virtual learning environments and providing access to open education resources (OERs). This is the case with the JISC Practising Open Education Project (2010-2011)[23] with six art, design and media departments in UK universities. A number of these OERs include art work (photographs, drawings and videos), but the majority are art theory, mostly research papers, dissertations and art education research documents produced by artists-teachers-researchers as part of their continuing professional development. These are distributed with Creative Commons licenses with varying degrees of freedom, but rarely have the ‘copyleft’ attitude that has been associated with the free software.

Such an enterprise can be interpreted in the light of current debates in the fields of immaterial labour and cognitive capitalism revealing that whilst (digital) art becomes postproduction, art education is being packaged into open resources that circulate as part of the capitalist system, and become central to the new eLearning/networked economies. In addition to filling a gap in subject-specific open resources, this raises the question: why is the free and the open so popular in contemporary art education? A cynical hypothesis is that art education, by declaring itself as a type of production of knowledge, attempts to gain a new legitimacy, in the bureaucratised global knowledge market. The other possibility is that in the face of such a doomed scenario, art education searches for new possibilities beyond pure commercialism, reclaiming access through “contingencies of opening and mobility of cognitive packages beyond confines of ownership.” [24]

1. Floss as artistic –pedagogical method

The Digital Artists Handbook

The digital handbook, published by the arts organisation folly and artists’ collective GOTO10 in 2008, aims to give artists information about the available tools and the practicalities related to Free/Libre Open Source Software and Content such as collaborative development and licenses.

FLOSS+Art

This book edited by Aymeric Mansoux and Marloes de Valk in 2008 reflects critically on the growing relationship between Free Software ideology, open content and digital art. With contributions by: Fabianne Balvedi, Florian Cramer, Sher Doruff, Nancy Mauro Flude, Olga Goriunova, Dave Griffiths, Ross Harley, Martin Howse, Shahee Ilyas, Ricardo Lafuente, Ivan Monroy Lopez, Thor Magnusson, Alex McLean, Rhea Myers, Alejandra Maria Perez Nuñez, Eleonora Oreggia, oRx-qX, Julien Ottavi, Michael van Schaik, Femke Snelting, Pedro Soler, Hans Christoph Steiner, Prodromos Tsiavos, Simon Yuill. Available both in print and as torrent download

Technology Will Save Us

The project by Daniel Hirschman & Bethany Koby is a haberdashery for technology and alternative education space dedicated to helping people to produce and not just consume technology.

Openlab

Openlab Workshops was started by artist and educator Evan Raskob in mid-2009 to fulfil the need for practical education about digital art and technology. Floss workshops are developed and taught by working artists and media practitioners, giving participants direct access to practical experience.

GOTO10

GOTO10 is an artists’ collective that organises floss workshops on subjects such as Pure Data, Linux audio tools, physical computing, SuperCollider, puredyne, RFID, Audio Signal Processing, and other related areas of practice.

UpStage

UpStage is an Open Source platform for cyberformance and education: remote performers combine images, animations, audio, web cams, text and drawing in real-time for an online audience. Initiated by the globally dispersed performance troupe Avatar Body Collision, it runs the annual Upstage festival, open to proposals.

2. Self-organised and self-managed art education

Really Free School

Free school based in a squatted London pub. “Amidst the rising fees and mounting pressure for ‘success’, we value knowledge in a different currency; one that everyone can afford to trade. In this school, skills are swapped and information shared, culture cannot be bought or sold. Here is an autonomous space to find each other, to gain momentum, to cross-pollinate ideas and actions.” (Communiqué #1)

Bruce High Quality Foundation University

A free university project set up by NY-based artists’ collective The Bruce High Quality Foundation. “We believe in the artistically educational possibilities of collaboration. Collaboration, as we mean it, means a group of concerned people come together to hash out ideas, try to figure out the world around them, and try to take some agency within its future. That’s the why and how of The Bruce High Quality Foundation. BHQFU is an attempt to extend the benefits of this collaborative model to a wider number of people.”

Unitednationsplaza

A temporary, experimental school in Berlin, initiated by Anton Vidokle following the cancellation of Manifesta 6 on Cyprus, in 2006. Developed in collaboration with Boris Groys, Liam Gillick, Hatasha Sadr Haghighian, Nikolaus Hirsch, Martha Rosler, Walid Raad, Jalal Toufic and Tirdad Zolghadr, the project travelled to Mexico City (2008) and, eventually, to New York City under the name Night School (2008-2009) at the New Museum. Its program was organized around a number of public seminars, most of which are now available in their entirety online.

FOSSter creative Learning

Lesson plans that can be used in the art classroom, developed by The FOSSter Creativity Team, a group of students of the University of the Arts (USA)

3. Open Source Repositories

University of the Arts institutional OER repository

University for the Creative Arts institutional OER repository

VADS (Visual Arts Data Service) A collection of over 100,000 art and design images that are freely available and copyright cleared for use in learning, teaching and research in the UK.

OER Commons A repository of materials about teaching, technology, research in the emerging field of Open Education. Art materials at OER commons.

You can find paula’s original article on Collaboration and Freedom – The World of Free and Open Source Art http://p2pfoundation.net/World_of_Free_and_Open_Source_Art

This article is part of the Furtherfield collection commissioned by Arts Council England for Thinking Digital. 2011

How can designers and programmers work more harmoniously? How can the tools being created better meet the needs of users? There is a need for designers to have a greater role in the production of the tools that they use, aside from just reporting bugs, requesting features or designing logos for open source projects. This is where the Libre Graphics Research Unit comes in. The Libre Graphics Research Unit (LGRU) is a traveling lab where new ideas for creative tools are developed. The unit has grand aims, looking to bring aspects of open source software development to artistic practices. The programme, sponsored by many organisations in Europe, is split into four interconnected threads:

The first meeting, Networked Graphics, took place in Rotterdam from 7-10 December, 2011 and was Hosted by WORM. This second meeting, Co-Position, for which I was present, took place at venues across Brussels from 22-25 February 2012. Co-Position is described by LGRU as:

[…] an attempt to re-imagine lay-out from scratch. We will analyse the history of lay-out (from moveable type to compositing engines) in order to better understand how relations between workflow, material and media have been coded into our tools. We will look at emerging software for doing lay-out differently, but most importantly we want to sketch ideas for tools that combine elements of canvas editing, dynamic lay-out, networked lay-out, web-to-print and Print on Demand.

The meeting saw the coming together of many international artists, theorists and developers for four days of work around this subject. As some of the sessions of the meeting took place simultaneously I’m unable to give a full synopsis of the event. Instead, what is presented below are some of the key issues raised at the meeting.

The subject of copyright cannot be avoided when discussing digital art and collaborative practices. There is a definite need to foster a safe and welcoming environment for artists and designers to produce, share and remix their work. Licensing of artwork under Copyleft licences – such as Creative Commons – helps to create this environment.

In his presentation, entitled “Libre Workflows – A Tragedy In 3 Acts”, Aymeric Mansoux was quick to point out that Creative Commons licences do not cover the source of the artwork. To put it into context, a JPG is covered by a Creative Commons licence but is the XCF/PSD file? Mansoux also considered what is actually a finished piece of artwork? In a remix culture is an artwork ever finished? Mansoux refers to this quote from Michael Szpakowski for further elaboration:

I’ve found it helpful to think of any artwork, be it literary, visual art or music as a kind of fuzzy four dimensional manifold. So the “complete” artwork is the sum of all its instances in time, and all epiphenomena. The entire artwork, seen this way, is a real and precisely enumerable sum, a concrete, not imaginary, set, which could be knowable in its entirety by something long lived and far seeing enough.

From their home town of Porto, Portugal, Ana Carvalho and Ricardo Lafuente produce Libre Graphics Magazine with ginger coons who is based in Toronto, Canada. For the production of the magazine they use Git, with their repository being hosted on Gitorious. As a tool for sharing files between collaborators Git is very useful. However, they explained that they feel they are not making effective use of all that Git has to offer. Part of this comes from the complexity of using Git. There are more than 140 commands in Git, each with their own unique function. These are usually entered via the command-line, but there are a number of programs with a Graphical User Interface (GUI) available. Programs with a GUI are usually favoured over command-line programs as they remove some of the complexity. Carvalho and Lafuente have found, however, that many of of these GUI programs simply replace commands with buttons, which doesn’t remove any of the complexity in using Git. What is needed is an easy to use specialised tool for the production of art.

In this work session, presented by Ana Carvalho and Eric Schrijver, the work group imagined how to adapt existing version control tools to meet the needs of artists and designers. The session began by taking a look at how people currently implement version control. A common practice is to manually make backups, renaming files to differentiate between stages. This can be an effective way of making different versions, but it doesn’t address other issues such as making comparisons or merging changes. The ineffectiveness of these manual methods is soon very apparent. The work group was introduced to the Open Source Publishing (OSP) Visual Repository viewer, which begins to respond to some problems with current version control systems by providing thumbnails of files in a repository.

Using this as a basis we began to look at other functions that the OSP Visual Repository viewer should have, such as the ability to compare graphical files in different ways and to revert back to previous versions or merge versions. Although there was no time to produce working code we did seek to address the complex task of merging and comparing not only the ouput file but also the working files (svg/xcf/psd).

Every good work of software starts by scratching a developer’s personal itch.

This quote from The Cathedral and the Bazaar by Eric Steve Raymond could not be more accurate in describing the motivations behind the development of Laidout, developed by Tom Lechner, a comic artist from Portland, Oregon. Perhaps one of the most impressive software demonstrations of LGRU, Laidout is a program for laying out artwork on pages with any number of folds, which don’t even have to be rectangular.

In an attempt to devise new tags that can be added to the SVG specification, Michael Murtaugh and Stephanie Villayphiou presented a work session that looked at the different ways language is interpreted by both humans and computers. To address this the work group took part in a task that saw them act as an interpreter of commands. With nothing more than a list of tags used in SVG files the work group would attempt to construct shapes.

The results varied from person to person and highlighted an important question: How can computers interpret ambiguity

Using the Richard A Bolt “Put that there” demonstration, Murtaugh showed how human-computer interaction is still based around using very clear, unambiguous commands that can be easily interpreted by computers. In SVG only the most basic of shapes – rectangles, circles and lines – are represented. But, as the work group participants asked, could there be tags to represent more complex shapes, such as a horse?

On the final day of the meeting I took part in a roundtable discussion, chaired by Angela Plohman and featuring myself, Stephanie Vilayphiou, Camille Bissuel and Ana Carvalho. The discussion first went over all that we had achieved over the four days at the meeting, and then the discussion focused on how and why we share our artwork. Expanding on the earlier quote from Szpakowski, how can we make sharing all of our artwork – including the early stages and inspirations behind it – an easier and integrated part of making artwork? In addition to sharing our final, “finished” artworks do we want to also share our processes and ideas behind the artwork? More importantly, can software easily aid this?

Other topics debated in the discussion revolved around opening up our artwork and processes to others. By opening up the development process of our artwork do we do so to invite collaborators and contributions or just observers? The Blender Open projects, for example, are highly regarded as an example of the work that can be made using open source software. The files used to make these projects are are released upon completion of the project, but the development process remains closed to the team of artists and developers. Would opening up this process to contributors add any value or could having too many ideas dilute the original vision of the project.

Although no conclusions around these topics were made, it was nonetheless important for everyone at the meeting to think critically about their practice

A concern of mine is that research is not always acted up on and exciting possibilities exist only as theory. However, I feel that the approach of Libre Graphics Research Unit, which combines research and practice, will ensure that the work undertaken at the meetings is implemented. It is actively working with developers and users to try and create solutions.

At the Co-Poistion meeting not one final product was made, but the initial vision for the future of layout was formed.

The next meeting, Piksels and Lines, takes place in Bergen, Norway and is organised by Piksel.