Featured image: Pandora’s Dropbox by Matt Bower

The Disruption Network Lab (DNL) has been presenting in Berlin some of the finest platforms for the discussion of art, hacktivism and disruption, presenting academic debates on not-so-conventional forms of thought. In their event IGNORANCE: The Power of Non-Knowledge, the second in the series Art and Evidence, various scientists and researchers discussed ignorance, not merely as a subaltern issue but as a central tool in knowledge production.

In previous events, DNL debated how ignorance is deployed as a mechanism of truth and power negotiation, mainly through the omission of the known by the means of secrecy, obfuscation and military classification. There are many forms of understanding ignorance, and this program intended to elucidate the potentialities and pitfalls within the concept. According to DNL, the first step towards approaching ignorance is to recognise it and become aware of it. As co-curator of DNL Daniela Silvestrin said (despite the paradox) that it is necessary to render the “unknown unknown into a known unknown.” The field of ignorance studies investigates the spread of ignorance, what kind of forms it takes depending on the context, how science “converts” it into probabilistic calculations of risk, and even how it can be used to push certain political, economical or religious agendas.

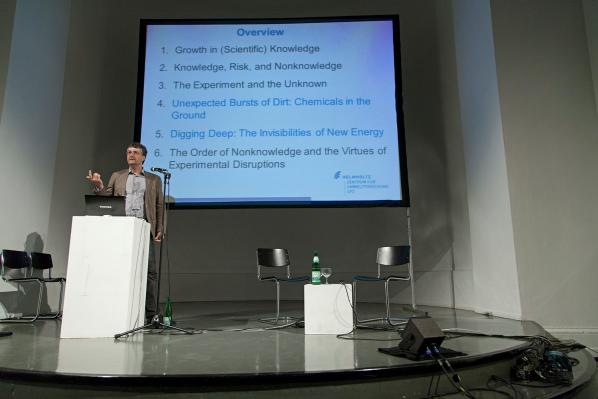

In the opening keynote, Matthias Gross, a sociologist and science studies scholar who has written extensively on ignorance studies, co-editing with Linsey McGoey the “Handbook of Ignorance Studies,” starts by stating that “new knowledge always creates new ignorance” and that throughout history humans have been in constant relation – acceptance, denial, resignation – with the unknown. Gross has covered how ignorance operates in different scientific milieus, namely, how risk is widely used in natural sciences as an attempt to project an idea of the future, as demonstrated in weather forecasting, but also how not knowing operates in everyday life; through secrets, the spread of false knowledge, feigning ignorance, or even through actively not wanting to know.

Gross presented a compelling body of research, exposing numerous examples in which ignorance serves the purpose as a tool to acknowledge what we don’t know in science (important in fields such as Epidemiology) or how positions of power use ignorance to manipulate public opinion within our social structures. However, the debate felt somehow stranded in an optimistic loop, where ignorance was seen mostly as a catalyst to search for further knowledge. Yet, I believe, while duelling with the binary knowledge vs ignorance, one should never forget to tackle the universalistic shape that ‘knowledge’ tends to adopt. In the end, the discussion felt insufficient, failing to examine knowledge/ ignorance from a non-hegemonic perspective when it would have been interesting to borrow criticism from postcolonial or feminist thought.

The first panel, moderated by Teresa Dillon, was deemed to shake the consensus in the room by joining the moralistic perspectives in science, the forbidden and undesired, the paranormal and the apocryphal together. Sociologist Joanna Kempner presented astonishing research focused on ‘negative knowledge,’ described as taboo, dangerous or threatening to the status quo. In an attempt to demystify the neutrality of knowledge production in sciences, Kempner interviewed various scientists to discover forbidden areas in their fields. The outcome of this research revealed that due to a fear of loss of funding and/ or sullying their reputation, scientists restrain themselves from researching illegitimate topics. For example, in Psychology one is expected not to study extra-sensory/ paranormal senses as these studies are usually associated to parasciences, a term that is in itself revealing of the hierarchies of knowledge. Kempner also exemplified how knowledge production is pressured by political interests and recalled the research-bans during the G.W.Bush government that cut funds to research related to sex and drugs under the assumption that remaining ignorant about any possible positive aspects (of recreational drug consumption) guarantees the maintenance of conservative moral values.

On the maintenance of moral values, the philosopher Jan Wieland presented an interesting experiment: “What would you do if you wouldn’t know? And what would you do if you’d know?” Giving the example of a social experiment by Fashion Revolution, a movement that calls for “greater transparency in the fashion industry”, Wieland examined consumers’ choices as they acknowledged the conditions in which clothing is actually produced. The project invokes a sentimental story with an excerpt from the daily life of a young girl living in Dhaka, Bangladesh, who works in a garment factory. Coming to terms with the girl’s story, the reactions differed — from not buying and empathically connecting with her situation to total indifference and still buying. Wieland attempts to analytically evaluate their intentions, good or bad, and how ignorance affects choices, stating that some of us might willfully remain ignorant (willful ignorance) as a way to better cope with our habits of consumption. However, I find it difficult to extrapolate these findings to a moralistic and individualistic criticism of people’s consumerist choices, since we know there is a structure that keeps consumers far from well-informed. A good example of how economy capitalises on ignorance, we know that the international division of labour is intentionally built to alienate the consumers from the “dirty” phases of production.

Jamie Allen, artist and researcher, also analyses at the economy of non-knowledge that is in the genesis of apocryphal technologies. “Do pedestrian’s crossroads’ buttons actually work?” We have all thought about this, yet has it stopped us from pressing the buttons? As long as we do not know whether a certain technology actually works, it “works”. Such an economy is boosted by acknowledging that some things remain as common ignorance. If we are not sure whether a lie detector works or not, then it can be used to incriminate — amidst ignorance, it shall produce the truth.

Informative and somewhat frightening, “Merchants of Doubt”, directed by Robert Kenner (2014), reveals how bendable ‘truth’ is in the interests of big corporations. The documentary investigates how the tobacco industry spread false information among firefighters, leading the world to believe that the domestic fires caused by cigarettes were the fault of the furniture rather than the cigarettes. This is where it goes from uncannily funny to scary. While interviewing scientists, whistleblowers and activists, the film unveils the dreadful story of corporate campaigns designed to unleash confusion and scientific scepticism among the masses, putting the life and security of millions at stake. This scepticism is not passive, thus it turns into a cynical endeavour. As corporations claim that there is no consensus surrounding issues such as global warming, conferences and books are forged to sustain their statement, while scientists who defend the existence of greenhouse gases are accused of ceding to their political biases in order to get funding for their research. What about facts? They seem to become irrelevant in the face of expensive lies.

Watch Merchants of Doubt’s trailer here.

Karen Douglas, a social psychologist, presented an empirical study of conspiracy theories whilst trying to trace a particular psychological profile of those more prone to elaborate and believe in them. Douglas used widely known conspiracy theories as examples, such as the infamous car crash that killed Princess Diana (which became a true “Schrödinger’s cat” case, instigated by the media-produced hyperreality in which Diana was both alive and dead — along with Elvis Presley) and the theory that 9/11 was orchestrated by the United States government to instigate and justify the “war on terror”. Douglas believes we are naturally hardwired to believe in conspiracy theories and sees them as a way to cope with things we are unable to answer. A socio-analytical view on conspiracy theories also seems to fail the complexity of forces that make us consider why certain theories are conspiracies and other perspectives are just theories. The issue with Douglas’ approach lies within its socio-psychological analysis, which tries to find a pathological pattern in people who believe in conspiracy theories, such as describing these people as being intentionally biased, or stating that those who tend to perceive patterns in things or believe in more than one conspiracy theory all show the “symptoms” of a conspiracy theorist. Yet, as pointed out by a member of the audience, this approach seems to lack a sensibility to the entire concept of “conspiracy theory” as a political tool to dismiss and undermine other narratives, such as narratives from an undesired other (e.g. how Russia’s government agenda is seen by the USA). Nevertheless, it is interesting to understand how these bodies of “disbelief”, should you wish to call them conspiracy theories or not, have a huge impact on our lives and inevitably our deaths (e.g. global warming, vaccination). As with apocryphal technologies, certain forms of unknown seem to crystallise as forms of knowledge – we know that we do not know and that is the way it is.

The closing panel, moderated by Tatiana Bazzichelli, has overseen our entanglement on social media and its algorithms, promising to be oracles of truth while their complex structures grow beyond our understanding. Ippolita, a group of activists and writers, warned how social media promotes emotional pornography, where our feelings are exploited by click baits in exchange for our personal data. By establishing clear metrics of interaction, like the number of likes and comments, social media creates an addictive game of forged interactivity, while we are scrutinised by biometric evaluation resultant from the same data we produce. Also analysing the manipulation of data and its weight in political agendas, Hannah Parkison, a journalist focused on digital culture, analysed Trump’s run for presidency propaganda in digital media. By using mostly social networks, such as Facebook and Twitter, Trump has kept control of his narrative without entering into risky interviews broadcast on TV. This is an effective way to get away with lies, regardless of the constant warnings from fact checkers – according to Politict 78% of what Trump said on the run for the election is not factually true. These lies spread across the internet, rendering their own truth.

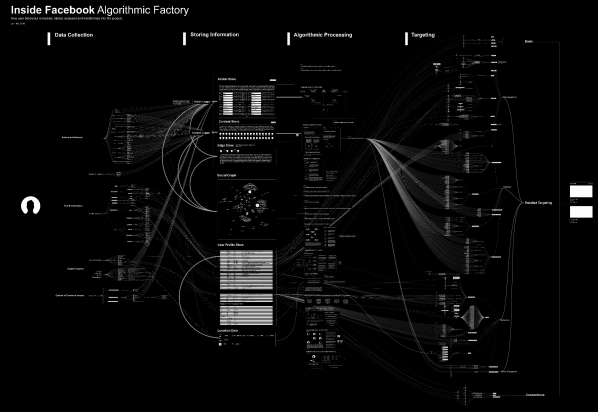

Vladan Joler, chair of New Media Department at the University of Novi Sad, presented his project in which he tries to map the tentacular structure of the Facebook algorithm, an expansive database incorporating individuals’ personal information that implies the fabrication of assumptions about potential consumers’ habits, wants and needs. Facebook was thus framed as an immaterial factory of information, the functioning of its assembly line still unknown, constantly mutating and growing. A speculative visual image of Facebook’s processes was rendered as Vladan tried to map something unknown; this mapping has similarities to the work of early cartographers. And much like early anthropological stances, the nodes of information produced have the potential to define thoughts and discussions about what we are and how we are supposed to behave. As Vladan ironically concluded, these are the tools used by the cybernet dominators – the digital monarchies that will accentuate asymmetries.

Ideas such as ‘knowledge’ find resistance and defiance from other epistemes that fall out from the western-centric productions of knowledge, such as the Amerindian ‘perspectivism’ defended by Viveiros de Castro or even the Alien phenomenologies (see Ian Bogost) that instigate the thought of non-anthropocentric ontologies. Bearing those in mind, I found that talking about the ‘dark’ side of knowledge is an invitation to dismantle and boycott its mechanisms of production, sustained in frail ideas of “truth”, “reality”, or “science”. In addition to the initial concept of ignorance, the conference provided a fertile ground for questioning the multiple ways in which humans deal with intangible phenomena, try to bypass obscurity and profit from that same obscurity. It provided insight on the relevance of knowledge to map and create reality, while bodies of power render webs of mystification of the tangible – corporations forging lies, politics of manipulation, cultural colonisation – reproducing ad nauseam epistemic violence.

The third edition of the Art and Evidence series from Disruption Network Lab, which took place on the 25th and 26th of November, wrapped up with the event TRUTH-TELLERS: The Impact of Speaking Out. TRUTH-TELLERS asks a question that could not be more crucial at the moment: “Can we trust the sources and can the sources trust us?” We have recently experienced a presidential battle between Clinton and Trump in which one of the most divisive topics were the thousands of emails sent to and from Hillary Clinton’s private email server while she was Secretary of State. A battle from which Trump left victorious despite having failed almost every fact-checking test. While Assange is forbidden to use the Internet for fear of him interfering with the presidential run in the USA, Chelsea Manning remains convicted, sentenced to 35 years of imprisonment due to her 2013 accusations of violating the Espionage Act. DNL gathered hacktivists, privacy advocates, investigative journalists, artists and researchers to “reflect on the consequences of leaking and whistleblowing from a political, cultural and technological perspective”. Unfortunately, due to a lack of funding, this could have been the very last DNL event. Let’s hope not, as these are vital, particularly in times of political despair.

Co-published by Furtherfield and The Hyperliterature Exchange.

Last October I received an e-mail headed “Introducing Vook”:

The Vook Team is pleased to announce the launch of our first vooks, all published in partnership with Atria, an imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc. These four titles… elegantly realize Vook’s mission: to blend a book with videos into one complete, instructive and entertaining story.

The e-mail also included a link to an article about Vooks in the New York Times:

Some publishers say this kind of multimedia hybrid is necessary to lure modern readers who crave something different. But reading experts question whether fiddling with the parameters of books ultimately degrades the act of reading…

Note the rather loaded use of the words “lure”, “crave”, “fiddling” and “degrades”. The phraseology seems to suggest that modern readers are decadent and listless thrill-seekers who can scarcely summon the energy to glance at a line of text, let alone plough their way through an entire book. If an artistic medium doesn’t offer them some form of instant gratification – glamour, violence, excitement, pounding beats, lurid colours, instant melodrama – then it simply won’t get their attention. But publishers have a moral duty not to pander to their readers’ base appetites: the New York Times article ends by quoting a sceptical “traditional” author called Walter Mosley –

“Reading is one of the few experiences we have outside of relationships in which our cognitive abilities grow,” Mr. Mosley said. “And our cognitive abilities actually go backwards when we’re watching television or doing stuff on computers.”

In other words, reading from the printed page is better for your mental health than watching moving pictures on a screen: an argument which has been resurfacing in one form or another at least since television-watching started to dominate everyday life in the USA and Europe back in the 1950s. To some extent this is the self-defence of a book-loving and academically-inclined intelligensia against the indifference or hostility of popular culture – but in the context of a discussion of Vooks, it can also be interpreted as a cry of irritation from a publishing industry which is increasingly finding the ground being scooped from under its feet by younger, sexier, more attention-grabbing forms of entertainment.

The fact that the Vook publicity-email links to an article which is generally rather sniffy and unfavourable about the idea of combining video with print no doubt reflects a belief that all publicity is good publicity – but it is also indicative of the publishing industry’s mixed attitudes towards the digital revolution. On the whole, up until recently, they have tended to simply wish it would just go away; but they have also wished, sporadically, that they could grab themselves a piece of the action. But those publishers who have attempted to ride the digital surf rather than defy the tide have generally put their efforts and resources into re-packaging literature instead of re-thinking it: and the evidence of this is that the recent history of the publishing industry is littered with ebooks and e-readers, whereas attempts to exploit the digital environment by combining text with other media in new ways have generally been ignored by the publishing mainstream, and have therefore remained confined to the academic and experimental fringes.

The publishing industry’s determination to make the digital revolution go away by ignoring it has been even more evident in the UK than in the US. The 1997 edition of The Writers’ and Artists’ Yearbook, for example, contains no references to ebooks or digital publishing whatsoever, although it does contain items about word-processing and dot-matrix printers. On the other hand, Wired magazine was already publishing an in-depth article about ebooks in 1998 (“Ex Libris” by Steve Silberman, http://www.wired.com/wired/archive/6.07/es_ebooks.html) which describes the genesis of the SoftBook, the RocketBook and the EveryBook, as well as alluding to their predecessor, the Sony BookMan (launched in 1991). Even in the USA, however, enthusiasm for ebooks took a tremendous knock from the dot-com crash of 2000. Stephen Cole, writing about ebooks in the 2010 edition of The Writers’ and Artists’ Yearbook, summarises their history as follows:

Ebook devices first appeared as reading gadgets in science fiction novels and television series… But it was not until the late 1990s that dedicated ebook devices were marketed commercially in the USA… A stock market correction in 2000, combined with the generally poor adoption of downloadable books, sapped all available investment capital away from internet technology companies, leaving a wasteland of broken dreams in its wake. Over the next two years, over a billion dollars was written off the value of ebook companies, large and small.

After 2000, there was a widely-held view (which I shared) that the ebook experiment had been tried and failed: paper books were a superb piece of technology, and perhaps a digital replacement for them was simply never going to happen. There were numerous problems with ebooks: too many different and incompatible formats, too difficult to bookmark, screens hard to read in direct sunlight, couldn’t be taken into the bath, etc. But ebooks have always had a couple of big points in their favour – you can store hundreds on a computer, whereas the same books in paper form demand both physical space and shelving, you can find them quickly once you’ve got them, and they’re cheap to produce and deliver. Despite the dot-com crash and general indifference of the reading public, publishers continued to bring out electronic editions of books, and a small but growing number of people continued to download them.

Things really started to change with the launch of Amazon’s Kindle First Generation in 2007. It sold out in five and a half hours. With the Kindle, the e-reader went wireless. Instead of having to buy books on CDs or cartridges and slot them into hand-helds, or download them onto computers and then transfer them, readers using the Kindle could go right online using a dedicated network called the Whispernet, and get themselves content from the Kindle store.

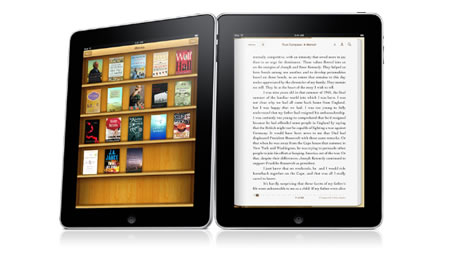

Despite this big step forward, the Kindle was still an old-school e-reader in some respects: it had a black and white display, and very limited multimedia capabilities. The Apple iPad changed the rules again when it was launched in April 2010. The iPad isn’t just an e-reader – it’s “a tablet computer… particularly marketed for consumption of media such as books and periodicals, movies, music, and games, and for general web and e-mail access” (Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/I-pad). Its display screen is in colour, and it can play MP3s and videos or browse the Web as well as displaying text. For another thing, it goes a long way towards scrapping the rule that each e-reader can only display books in its own proprietary format. The iPad has its own bookstore – iBooks – but it also runs a Kindle app, meaning that iPad owners can buy and display Kindle content if they wish.

It seems we may finally be reaching the point where ebooks are going to pose a genuine challenge to print-and-paper. Amazon have just announced that Stieg Larsson’s The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo has become the first ebook to sell more than a million copies; and also that they are now selling more copies of ebooks than books in hardcover.

It is certainly also significant that the past couple of years have seen a sudden upsurge of interest in the question of who owns the rights over digitised book content, and whether ordinary copyright laws apply to online text – a debate which has been brought to the boil by a court case brought against Google in 2005 by the Authors Guild of America.

In 2002, under the title of “The Google Books Library Project”, Google began to digitise the collections of a number of university libraries in the USA (with the libraries’ agreement). Google describes this project as being “like a card catalogue” – in other words, primarily displaying bibliographic information about books rather than their actual contents. “The Library Project’s aim is simple”, says Google: “make it easier for people to find relevant books – specifically, books they wouldn’t find any other way such as those that are out of print – while carefully respecting authors’ and publishers’ copyrights.” They do concede, however, that the project includes more than bibliographic information in some instances: “If the book is out of copyright, you’ll be able to view and download the entire book.” (http://books.google.com/googlebooks/library.html)

In 2004 Google launched Book Search, which is described as “a book marketing program”, but structured in a very similar way to the Library Project: displaying “basic bibliographic information about the book plus a few snippets”; or a “limited preview” if the copyright holder has given permission, or full texts for books which are out of copyright – in all cases with links to places online where the books can be bought. Interestingly, my own book Outcasts from Eden is viewable online in its entirety, although it is neither out of copyright nor out of print, which casts a certain amount of doubt on Google’s claim to be “carefully respecting authors’ and publishers’ copyrights”.

In 2005 the Authors Guild of America, closely followed by the Association of American Publishers, took Google to court on the basis that books in copyright were being digitised – and short extracts shown – without the agreement of the rightsholders. Google suspended its digitisation programme but responded that displaying “snippets” of copyright text was “fair use” under American copyright law. In October 2008 Google agreed to pay $125 million to settle the lawsuit – $45.5 million in legal fees, $45 million to “rightsholders” whose rights had already been infringed, and “$34.5 million to create a Book Rights Registry, a form of copyright collective to collect revenues from Google and dispense them to the rightsholders. In exchange, the agreement released Google and its library partners from liability for its book digitization.” (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Google_Book_Search_Settlement_Agreement). The settlement was queried by the Department of Justice, and a revised version was published in November 2009, which is still awaiting approval at the time of writing.

The settlement is a complex one, but its most important provision as regards the future of publishing seems to be that “Google is authorised to sell online access to books (but only to users in the USA). For example, it can sell subscriptions to its database of digitised books to institutions and can sell online access to individual books.” 63% of the revenue thus generated must be passed on to “rightsholders” via the new Registry. “The settlement does not allow Google or its licensees to print copies of books in copyright.” (“The Google Settlement” by Mark Le Fanu, The Writers’ and Artists’ Yearbook 2010, pp. 631-635).

Google, it will be noted, are now legally within their rights to continue their digitisation programme. This means they don’t have to ask anyone’s permission before they digitise work. If authors or publishers would prefer not to be listed by Google it is up to them to lodge an objection online. Google would argue that in launching their Library Project and Books Search they have merely been seeking to make their search facilities more complete, and thus to “make it easier for people to find relevant books” – but whether or not they have been deliberately plotting their course with wider strategic issues in mind, the end result has been to make them the biggest single player – almost the monopoly-holder – where digital book rights are concerned. As a reflection of this, an organisation called the Open Book Alliance has been set up to oppose the settlement, supported by the likes of Amazon and Yahoo: “In short,” their website claims, “Google’s book digitization strategy in the U.S. has focused on creating an impenetrable content monopoly that violates copyright laws and builds an unfair and legally insurmountable lead over competitors.” (http://www.openbookalliance.org/)

Whatever the pros and cons of the Google Settlement, it has undoubtedly helped to focus the minds of writers and publishers alike on the question of digital rights. Copyright laws and publishers’ contracts were designed to deal with print and paper, and until very recently there has been almost no reference at all to electronic publication. Writers who have agreed terms with a publisher for reproduction of their work in print have theoretically been at liberty to re-publish the same work on their own websites, or perhaps even to collect another fee for it from a digital publisher; and conversely, publishers who have signed a contract to bring out an author’s work in print have sometimes felt free to reproduce it electronically as well, without asking the writer’s permission or paying any extra money.

But things are beginning to change. A June 2010 article in The Bookseller notes that Andrew Wylie, one of the most prestigious of UK literary agents, “is threatening to bypass publishers and license his authors’ ebook rights directly to Google, Amazon or Apple because he is unhappy with publishers’ terms.” This is partly because he believes electronic rights are being sold too cheaply to the likes of Apple: “The music industry did itself in by taking its profitability and allocating it to device holders… Why should someone who makes a machine – the iPod, which is the contemporary equivalent of a jukebox – take all the profit?” Clearly, electronic rights are going to be taken much more seriously from now on.

Further indications that authors, publishers and agents are beginning to wake up and smell the digital coffee can be found in the latest editions of The Writers’ and Artists’ Yearbook and The Writers’ Handbook. For those who are unfamiliar with them, these annual publications are the UK’s two main guides to the writing industry. The 2010 edition of The Writer’s Handbook opens with a keynote article from the editor, Barry Turner, entitled “And Then There was Google”. As the title indicates, its main subject is the Google settlement and its implications – but its broader theme is that the book trade has been ignoring the digital revolution for too long, and can afford to do so no longer:

In the States… sales of e-books are increasing by 50 per cent per year while conventional book sales are static. An indication of what is in store was provided at last year’s Frankfurt Book Fair where a survey of book-buying professionals found that 40 per cent believe that digital sales, regardless of format, will surpass ink on paper within a decade.

The Writers’ and Artists’ Yearbook is more conservative in tone, but if anything its coverage is more in-depth. It has an entire section titled “Writers and Artists Online”, which leads with an article about the Google settlement. In addition there are articles on “Marketing Yourself Online”, “E-publishing” and “Ebooks”. Even in the more general sections of the Yearbook there is a widespread awareness of how digital developments are affecting the book trade. For example, there is a review (by Tom Tivnan) of the previous twelve months in the publishing industry, which acknowledges the importance not just of ebooks but print-on-demand:

Amazon’s increasing power underscores how crucial the digital arena is for publishing… Ebooks remain a miniscule part of the market,… yet publishers and booksellers say they are pleasantly surprised at the amount of sales… And it is not all ebooks. The rise of print-on-demand (POD) technology (basically keeping digital files of books to be printed only when a customer orders it) means that the so-called “long tail” has lengthened, with books rarely going out of print… POD may soon be coming to your local bookshop. In April 2009, academic chain Blackwell had the UK launch of the snazzy in-store Espresso POD machine, which can print a book in about four minutes…

There is also an article about “Books Published from Blogs” (by Scott Pack):

Agents are proving quite proactive when it comes to bloggers. Some of the more savvy ones are identifying blogs with a buzz behind them and approaching the authors with the lure of a possible book deal… Many bestsellers in the years to come will have started out online.

Most of the emphasis in these articles falls on the impact which digital developments are having on the marketing of books rather than the practice of writing itself. But now and again there are signs of a creeping awareness that digitisation may actually change the ways in which our literature is created and consumed. In The Writer’s Handbook, Barry Turner attempts to predict how the digital environment may affect the practice of writing in the coming years:

Those of us who make any sort of livng from writing will have to get used to a whole new way of reaching out to readers. Start with the novel. Most fiction comes in king-sized packages… Publishers demand a product that looks value for money… But all will be different when we get into e-books. There will be no obvious advantage in stretching out a novel because size will not be immediately apparent… Expect the short story to make a comeback… The two categories of books in the forefront of change are reference and travel. Their survival… is tied to a combination of online and print. Any reference or travel book without a website is in trouble, maybe not now, but soon.

Scott Pack’s article on “Books Published from Blogs” tends to focus on those aspects of a blog which may need remoulding to suit publication in book form; but an article by Isabella Pereira entitled “Writing a blog” is more enthusiastic about the blog as a form in its own right:

The glory of blogging lies not just in its immediacy but in its lack of rules… The best bloggers can open a window into private worlds and passions, or provide a blast of fresh air in an era when corporate giants control most of our media… Use lots of links – links uniquely enrich writing for the web and readers expect them… What about pictures? You can get away without them but it would be a shame not to use photos to make the most of the web’s all-singing, all-dancing capacities.

Even here, however, the advice stops short of videos, sound-effects or animations. Another article in The Writers’ and Artists’ Handbook (“Setting up a Website”, by Jane Dorner) specifically forbids the use of animations:

Bullet points or graphic elements help pick out key words but animations should be avoided. Studies show that the message is lost when television images fail to reinforce spoken words. The same is true of the web.

It’s a little difficult to fathom exactly what point Dorner is trying to make here, but it seems to be something along the lines that using more than one medium may have a distracting rather than enhancing effect. If the spoken words on your television are telling you one thing, but the pictures are telling you another, then “the message is lost”. Perhaps a more interesting point, however, is where Dorner draws her dividing-line between acceptable and unacceptable practice. “Bullet points or graphic elements” are all right, because they “help pick out key words”, but “animations should be avoided”. In other words visual aids are all very well as long as they remain to subservient to text. They minute they threaten to replace it as the focus of attention, they become undesireable.

Clearly this point of view continues to enjoy a lot of support, particularly from traditionalists in the writing and publishing industries. All the same, combinations of text with other media may be about to enjoy some kind of vogue; and the development of the Vook brand since its launch last October is an instructive case-history in this regard.

When Vooks were first launched it seems fair to say that they were broadly greeted with a mixture of indifference and scorn. Reviews which appeared in the first couple of months after the launch were usually either lukewarm of downright unfavourable. Here, for example, is one from Janet Cloninger, writing in The Gadgeteer, November 2009:

So how were the video clips? Have you ever seen any of those old 60s TV shows where they were trying to show a bad acid trip? You know the crazy camera work, the weird color changes, the really bad acting?… I don’t think they added anything to the story at all… I found they were very distracting while trying to read.

Here is another from the Institute for the Future of the Book:

In terms of form the result is ho-hum in the extreme, particularly as there doesn’t seem to be much attempt to integrate the text and the banal video, which seems to exist simply to pretty-up the pages.

Following on from this generally unenthusiastic reception for the first Vooks, news about the brand over the next few months seemed to suggest that it was struggling to establish itself. In January 2010 Vook announced that they were publishing a range of “classic” titles, mostly for children – since “classic” normally means “out of copyright”, this seemed to imply that they were trying to boost their titles-list on the cheap. In February there was an announcement that Vook had raised an extra $2.5 million in “seed-financing” from a number of Silicon Valley and New York investors, suggesting that perhaps initial sales had been disappointing, Simon & Schuster had been reluctant to put up more money, and new sources of finance had therefore been sought.

With the launch of the iPad, however, it became obvious that Vook was making another throw of the dice. In April they launched 19 titles specially adapted for the iPad: In a statement, Bradley Inman, Vook CEO and founder said, “We will remember the iPad launch as the day that the publishing industry officially made the leap to mixed-media digital formats and never looked back…” The Vook blog makes this pinning-of-hopes on the iPad even more apparent:

The release of the iPad this Saturday was not just a red letter moment for Silicon Valley, it marked a turning point for the publishing and film industries, and a great opportunity for those invested in the future of media. The team at Vook has been working hard for months to prepare apps for submission to Apple… In many ways, it seems like the iPad was literally made for us…

And it seems their hopes may not have been misplaced. In May they launched a title about Guns’n’Roses (Reckless Road, documenting the creation of the Appetite for Destruction album), and lo and behold it was favourably greeted:

…unprecedented photos and memorabilia from the early years of one of the great rock bands from the 1980s and 1990s… If you are a true hard rock fan, and Guns ‘N’ Roses was one of your favorite bands, this app is worth the try. (PadGadget)

Now that I’ve had some time to read through Reckless Road and watch many of the videos included in it I can see the value of the Vook approach. It lends itself well to a product like this… This is an app any Guns N’ Roses fan would greatly appreciate. (Joe Wickert)

In June, the Vook version of Brad Meltzer’s bestseller Heroes for my Son was also favourably received:

It is easy to see the tremendous possibilities in the Vook format, especially when tied to a tablet device like the iPad. I very much enjoyed my first experience with a Vook mainly because I rapidly dropped my attempt to think of it as a Book with video plug ins. A Vook is really a multimedia platform that centers around text, rather than a traditional book. (MobilitySite)

Both these books are non-fiction – a genre in which the relationship between video footage and text seems far less problematic. It is interesting to note, however, that in both cases the non-linear structure of the Vook is singled out as a positive feature, compared to the sequential organisation of a traditional book:

It is charmingly non-linear and can be approached from many different angles. More a chocolate box than a book, especially if you are like me and enjoy really digging down into a subject while reading. (MobilitySite)

Remember that old VH1 series, Behind the Music? Canter’s Vook app feels like a modern version of that approach, with the added benefit that you can hop around the story to your heart’s content… (Joe Wickert)

There are hints here of a realisation that digital media can sometimes offer kinds of reading which are unavailable to, or hampered by, traditional print-and-paper.

Further recognition that ebooks with multimedia in them might actually have market appeal came at the end of June from none other than Amazon, who announced that they were adding audio and video to the Kindle iPhone/iPad app. The irony of this move is, of course, that Kindle ebooks are now multimedia-capable on the iPhone and iPad but not on the Kindle itself – an irony which can hardly be allowed to continue, and which therefore doubtless presages the launch of a multimedia Kindle some time in the near future.

Of course, the story of multimedia innovation in literature goes back much further than Vooks and the iPad. The British writer Andy Campbell, for example, has been publishing his own new media fiction online for years – most recently on the Dreaming Methods website. Most of his work has been designed in Flash, which the iPad unfortunately does not support. He therefore finds himself in the one-step-forward-and-two-steps-back position where new media literature is finally starting to make some headway in the marketplace, but thanks to a whim of the Apple corporation his own work in the field, developed over more than a decade, been landed with a big disadvantage. Understandably, his feelings are mixed:

It does indeed seem like there is a shift going on with digital fiction, although there are still a large number of stumbling blocks from a development point of view… Whilst the potential of the iPhone and iPad is undoubtedly exciting, a lot of authors – including myself – do not work with Macs or have the programming experience required to produce Apple-happy content…. However that’s from the point of view of Apple dominating the market and forcing everyone to use their SDK, whilst in actual fact Android holds considerable promise… I wouldn’t say digital fiction is breaking through into the mainstream – although perhaps it depends what you mean by digital fiction… Whether anything has been produced that really takes reading as an experience to a new level, I’m not sure.

Since Flash has hitherto been one of the main tools used by new media writers and artists, many of them will now find themselves in the same predicament as Campbell – and many of them will doubtless be hoping, like him, that alternative platforms such as Android are going to make some headway in the coming months. But leaving the question of platforms on one side, another difficulty for existing new media writers seems to be that although publishers are suddenly discovering a new enthusiasm for the form, they have very little knowledge or understanding of the work which has already been done, and very few links with those who have been doing it. Nor is this entirely the publishers’ fault, because there seems to be a genuine cultural divide between those who work in the publishing industry and those who take an interest in new media literature. Emily Williams of Digital Book World alludes to this divide in her article about this year’s London Book Fair (“Old London vs. New Media”, April 2010):

In most [publishing] houses, the digital innovators are still operating on a parallel plane, touching on but not fully integrated into the publishers’ core business centers. This segregation is so complete that much of the digital crowd is liable to skip the traditional fairs altogether, gravitating instead to their own tech confabs (which are in turn often boycotted by, or unknown to, the bookish folk).

Michael Bhaskar, a publisher and one of the judges of the Poole Literary Festival’s New Media Writing Prize, makes a similar point in his blog:

There has been no real conversation between the two [publishers and new media writers]. Why? It seems like we should have hit the meeting point where there could and should be a productive alliance, when in fact the gulf seems as wide as ever… Publishers have to sell books – or something – to keep going… [whereas] much new media writing is not designed to be commercial, being associated with a more recondite and experimental mindset.

In other words, publishers and new media writers have failed to come together, not simply because publishers have been hoping for the digital revolution to go away, nor because new media writers have been go-it-alone experimentalists, but because culturally they have belonged to different worlds, moved in different circles and spoken different languages.

Even assuming that these difficulties can be overcome, it is open to doubt whether new media writers will necessarily want to throw themselves headlong into the commercial mainstream. Many of them, like Andy Campbell, have been going it alone for so long that the habit of independence may be difficult to shake. Undoubtedly a bit of money would be very welcome, but advice from marketing men about how to make their work more commercial might be less well-received. On the publishing side of the equasion, however, there are definite signs that things are starting to change. Experimentation was the buzzword of the 2010 London Book Fair:

The publishing industry must move at speed to adopt new business models and new ways of working if it is to seize the opportunities of the digital revolution, delegates were told at London Book Fair… Industry figures focused on the need to experiment and to get a real understanding of what consumers want from the new technologies in a fast-changing environment. (The Bookseller)

There are also signs that the influence of digital technology on writing now extends beyond the software-savvy fringe, and is starting to affect the ways in which less specialised writers create their work. One of the surprize best-sellers of last year was a book called Important Artifacts and Personal Property from the Collection of Lenore Doolan and Harold Morris, Including Books, Street Fashion and Jewellery, by Leanne Shapton, which (as the title suggests) takes the form of an auction catalogue, selling off the belongings of a fictional couple. As befits an auction catalogue, the book consists of photographs of the articles for sale, accompanied by snippets of text –

Lot 1231: Two pairs of white shoes. Two pairs of white bucks. The label inside the men’s pair reads “Prada”, the women’s reads “Toast”. Sizes men’s 11, women’s 9. Well worn. $40-60.

The artefacts in the catalogue are arranged in chronological order, which makes it easier for them to tell the story of the couple’s love-affair; but despite this concession to linearity what is striking about the novel, to anyone who has had very much to do with new media literature, is how like a piece of new media literature it is. Experimental it may be as a novel in print, but as a piece of digital writing it would be fairly conventional, albeit unusually well-put-together. It was obviously composed as collection of objects and pictures as much as a a piece of written text; there is no conventional dialogue or storytelling; despite its chronological sequence there is a strong non-linear element to the book, a feeling that it is as much designed to be dipped and skimmed as to be read from one end to the other; it makes a knowing reference to Raymond Queneau, the Oulipo writer; and in many ways it would be more at home on the Web, where the pictures could be in full colour and zoomable at no extra expense.

Another example of the influence of digital technology on “ordinary” literature comes from the small-scale end of the publishing industry – Martha Deed’s poetry chapbook The Lost Shoe, which was published earlier this year by Dan Waber at Naissance Chapbooks (about whom, more in a moment). The first point to note about this collection is that in order to publicise it Martha made a video, also called “The Lost Shoe” (http://www.sporkworld.org/Deed/lostshoe.mov), which deserves to be thought of as a companion-piece rather than a “trailer”. The poems in the collection are based on Martha’s experiences as a psychologist specialising in family law – more specifically, they deal with cases in which family members have done violence to each other, and some of them are harrowingly raw:

Upstairs, he tried twice to change his clothes

his fingers slippery with your blood…

You were looking at him

the last person you saw before your death

It bothered him, that lifeless stare,

so he stepped over your mother

your dying baby sister

and tried to close your eyes…

The video has the same combination of near-documentary authenticity and artistic control. It starts with a 911 telephone call from a man who has harmed his own children. There is a terrible moment when he is asked what has happened and he breaks into hysterical tears and says “They got stabbed”, as if somebody else might have done it. It ends with Martha reading aloud from one of her own poems, “Practice Tips”, which is based on the Center for Criminal Justice Advocacy‘s “Criminal Pre-Trial and Trial Practice”:

Play the tape 10 times at trial.

The jury will become accustomed to the carnage…

Obfuscate. Whine. Grandstand.

Fumble with your papers.

The fact that Martha feels equally at home working with both the written word and the camera, and therefore feels able to shoot her own video as a means of publicising her collection of poems, is an indication of the way in which digital technology is beginning to influence literary practice at grass-roots level. But the influence goes further. As well as conventional verse, her collection contains a number of visual poems – you could almost call them diagram poems – combining text with graphic design. “Jury Pool”, for example, shows a number of black stick-figures in and around the jury pool, labelled with reasons why they have been disqualified from the jury, or factors which will influence their outlook on the case: “Have to go back to school”, “Ate lunch with defendant’s mother”, “Crime victim”, “Don’t understand English”, and so forth. Including a diagram-poem such as this in a collection of poetry would not have been impossible before digital technology came along, but the fact that software packages such as Microsoft Word and Open Office Writer can handle images as easily as text, and make it simple to customise page-design without incurring any extra cost, means that poets now have an enormous range of experimental possibilities constantly at their fingertips.

Furthermore a lot of writers haven’t just moved beyond the pen or the portable typewriter to computers and word processing software; they have moved on to such things as blogs and web-pages, which have built-in multimedia capabilities. Sound-files and videos are rapidly becoming a normal part of the amateur writer’s working environment, and as a result the combination of text with other media is becoming a grassroots staple rather than a specialists-only field.

The Lost Shoeis published by Naissance Chapbooks, run by Dan Waber. A glance through Waber’s catalogue is enough to confirm the effect which digital technology is starting to have on poetic style. Amongst more formally conventional poetry he publishes, for example, Psychosis by Steve Giasson, which is based on comments collected by a YouTube posting of the shower scene from Psycho:

kthevsd Lame movies ? Kid I like all movies, old films, new films, etc. How is this classic lame ? Have you even ever watched it ? What would some 16 year old teenybopper know about cinema ? You probably have never even heard of Kurosawa and I bet you have never even seen a Daniel Day Lewis or Meryl Streep movie in your life. No wonder everyone laughs at your generations taste…

Or there is a collection by Jenny Hill called Regular Expressions: the Facebook status update poems –

Ron: I delivered a fucking BABY tonight! Yep, a fucking BABY!!!!!!!!! what did

u do today? Nursing school is AWESOME!!!!!!!

Someone asks if it was slimy, another wants

the placenta, most are stumped

at how to comment

on all your exclamation marks.

Then there is Watching the Windows Sleep by Tantra Bensko, which combines “fiction, poetry, and photographs”; or Open your I by endwar, which is “at times concrete, at times typoem, at times visual poem, at times conceptual poem, at times typewriter poem”. It is clear that the digital revolution has affected all of these collections in one way or another – either by making a wider range of experimental options available, or by providing them with their inspiration and subject-matter.

Of course, these are atypical exhibits, because Dan Waber, the publisher, is clearly interested in adventurous and experimental kinds of poetry. He also publishes a series called “This is Visual Poetry“, which now runs to about fifty full-colour booklets of visual poems, “answering the question [What is visual poetry?] one full-color chapbook at a time”, and answering it extremely variously. All the same, even allowing for Waber’s adventurous tastes, the fact that within a couple of years he has managed to put together fifty chapbooks of visual poetry, plus nineteen “conventional” poetry collections which often show clear signs of technological influence, is strongly suggestive of the directon in which things are moving.

Just as noteworthy is the business-model behind Waber’s publishing ventures. Basically, his operation relies on three key elements. The first is print-on-demand technology, which has almost completely done away with the printing expertise on which book production used to rely. These days, as long as writers can produce a competently-laid-out electronic original it can be turned into a book at the touch of a button. Colour reproduction is slightly more expensive than black-and-white, but not prohibitively so. Standards of reproduction are undoubtedly lower than they would be in the hands of a specialist printer, but most people never notice the difference. Self-publishing ventures such as Lulu (www.lulu.com) rely on this kind of print-on-demand process, and although Waber sends his electronic originals to the local print shop rather than using a completely automated online process, the technology is the same.

However, whereas the Lulu publishing process involves quite a bit of donkeywork (and usually a crash course in book-design and pagination) on the part of the author, the second key element of Waber’s publishing model is a drastically simplified and stringent set of layout criteria. Submissions to the visual poetry series must be “17 color images of visual poems of yours that are 600 pixels wide by 800 pixels tall”; and submissions to the Naissance chapbook series must be a maximum of 48 pages, in A4 portrait layout, with specified page-margins. Waber has designed a macro which takes Word files laid out according to these specifications and converts them instantaneously into print-ready book originals. This means that responsibility for the page layout is left squarely with the author – as Waber’s guidelines say, “all you need to do is make each page look how you want it to look… and we’ll convert it” – with the added effect that as long as authors stay within the guidelines, they are free to experiment as much as they like.

This combination of strict limitations and artistic freedom has undoubtedly helped to foster some of the adventurous design his chapbook series displays. At the same time, however, Waber has eliminated so much complexity from the publishing process that the third key element of the business model looks after itself: his costs (including time-costs) have come right down, to the point where he can show a modest profit on print-runs as low as ten units. All he has to do is decide whether he wants to publish something: if he does, he runs his macro, sends his print-ready file to the printer, and has ten copies of the chapbook in his hands within 24 hours. As he writes with understandable pride:

The beauty in all of this is no cash outlay. No huge print runs. No wondering if there’s grant money to support it, no worrying if it’ll actually sell enough to cover costs. It’s all profit after one copy sells… I am in a situation where because I make money off of every book I publish, all I need to do is find more books to publish. Because I de-complexified the process so completely.

Waber believes that his kind of venture represents the way forward for literary publishing in the era of digital technology, and he also believes that it is the kind of solution which can probably only come from outside the existing print industry, not from inside, because, as he puts it, “Big Publishing has a model that is blockbuster-based”. To explain this more fully, he cites an article by Clay Shirkey called “The Collapse of Complex Business Models“, which argues that big and complex businesses become unable to adapt to new circumstances, because their ideas about how they should operate become culturally embedded. If the new circumstances are sufficiently challenging then the only way forward will be for big organisations to collapse, and for new small ones, without the same culturally embedded assumptions, to take their place.

When ecosystems change and inflexible institutions collapse, their members disperse, abandoning old beliefs, trying new things, making their living in different ways than they used to… when the ecosystem stops rewarding complexity, it is the people who figure out how to work simply in the present, rather than the people who mastered the complexities of the past, who get to say what happens in the future.

This, argues Waber, is likely to be the ultimate effect of the digital revolution on the publishing industry; not simply dramatic changes in publishing formats and marketing methods, but a complete collapse of “Big Publishing”, and a multitude of small-scale, dynamic new ventures like his own, growing up out of the wreckage.

Clearly this is something that publishers themselves are worried about. As Michael Bhaskar writes in his blog for The Poole Literary Festival’s New Media Writing Prize,

On the writing side I often hear that people feel ignored by publishers.Essentially the world of commercial publishing is a closed shop unwilling to listen to the maverick, the outsider and the original, and will ultimately pay for this as audiences gravitate to newer and amorphous forms… This might be an argument for by-passing publishers or intermediaries altogether… [but] what I would like is mediation.

Clay Shirkey quotes the example of the “Charley bit my finger” video on YouTube to illustrate how production values have changed:

The most watched minute of video made in the last five years shows baby Charlie biting his brother’s finger… made by amateurs, in one take, with a lousy camera… Not one dime changed hands anywhere between creator, host, and viewers. A world where that is the kind of thing that just happens from time to time is a world where complexity is neither an absolute requirement nor an automatic advantage.

The “not one dime changed hands anywhere” line is perhaps a bit of an oversimplification. Wikipedia notes that “According to The Times, web experts believe the Davies-Carr family could earn £100,000 from ‘Charlie Bit My Finger’, mostly from advertisements shown during the video.” (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charlie_Bit_My_Finger) But the Davies-Carrs didn’t make or post the video with the intention of becoming celebrities or making money. They posted it so that it could be viewed by the boys’ godfather. The success of the video, in other words, owes nothing to its production values or to any marketing strategy, and everything to the environment created by YouTube and its viewers.

An alternative to the Big Publishing model is already with us, and despite odd viral phenomena like “Charlie Bit My Finger”, it consists in the main of very large numbers of small-scale products reaching small audiences, rather than small numbers of very high-profile products reaching huge audiences. This alternative model is enabled by digital technology, and it replaces high production values and market-minded editorial controls with the principle that people’s desire to publish themselves and to look at each other’s efforts is itself a profit motor. No single book published by Lulu, for example, has to sell a lot of copies for Lulu itself to make a profit – it’s the volume which counts. The same is true of YouTube, and it’s also true, on a much smaller scale, of Dan Waber’s enterprise.

YouTube is now crawling with people hoping to become the next viral phenomenon – and there are also a number of talented individuals who have built up sizeable audiences on YouTube and who are making decent amounts of money out of those audiences – but the really big money is being made not by the people who contribute material, but by YouTube itself. The same is true of print-and-paper publishing via Lulu. The removal of editorial constraint has greatly freed up and democratised the creative side of the publishing process, but on the other hand, a system where most writers made relatively small amounts of money compared to publishers and agents is being increasingly shoved aside by a new system where most creators make no money at all, while the publishers do very nicely.

Add to this the fact that YouTube is now in the hands of Google – the same Google which has been “creating an impenetrable content monopoly” over digitised books through the Google Books programme – and the future of publishing starts to look less like an open field for small enterprises, created by the collapse of big corporations, and more like a battleground where a few monster Web 2 corporations – Amazon/Kindle, YouTube/Google and Apple – are carving up the territory as fast as they can, much as the major European countries carved up Africa during the nineteenth century.

What the future really holds for the publishing industry is probably a mixture of these two scenarios. It’s unlikely that conventional publishing is going to disappear any time soon, but in a shrinking market publishers are going to be more and more reluctant to publish untried material, more and more inclined to go with material which seems to tap into an already-established audience. The celebrity biography or autobiography; the book of the comedy series; the first novel by a TV personality; these are already familiar. The book version of a popular blog and the “global distribution” edition of something which has already sold very well via the Web are going to become increasingly familiar in the near future. Add to this books with associated websites, increasing emphasis on ebooks, and a cautious trial of ebooks with interactive elements, and you have a pretty good picture of how the conventional publishing industry is shaping up to deal with the digital revolution.

In the meantime, entrepreneurs like Dan Waber are taking fuller advantage of the new possiblities offered by digital technology, and perhaps planting the seeds for a whole new generation of publishing houses; while writers like Martha Deed and Leanne Shapton, under the influence of the digital revolution, are redefining literary genres.

But one consideration which should not be overlooked in all this is the importance of open standards. The digital revolution itself is predicated not only on technical advances – such as broadband, print-on-demand, digital video and multimedia handheld devices – but on the Web itself, and in particular on the fact that the Web is non-commercial and belongs to all its users. Material which appears on the Web doesn’t have to comply with a proprietary format laid down by any one corporation: it has to comply with standards laid down by the World Wide Web Consortium. It is this open structure which has enabled the Web to develop so rapidly and to serve as a framework within which so many enterprises have been able to flourish. For the field of publishing to flourish in the same way, open standards need to prevail here as well – open standards for ebooks, for example, so that standards-complaint work will be viewable on a whole range of different devices. Only under those circumstances can small enterprises and individual artists stand some kind of chance against the big corporations.

http://www.hyperex.co.uk/reviewdigitalpublishing.php

© Edward Picot, August 2010

© The Hyperliterature Exchange

Image: SMartCAMP logo, all images courtesy of SMartCAMP

Part of New York’s Art Week, SMartCAMP, or social media art camp, took place on March 5th and 6th, at the Roger Smith Hotel in New York, a slightly unusual kind of place in that it’s a hotel with its own production company. That company’s artistic director, Matt Semler, who is also the director of The LAB Gallery, became interested in the ways Roger Smith marketers Adam Wallace and Brian Simpson were using platforms like Facebook and Twitter to build an online community. According to Semler, his curiosity “ultimately led to more questions than answers and we found ourselves wanting to bring the leaders in the social media (SM) art world together to talk about their process, goals and best practices. Once we came up with the name SMartCAMP we were pretty much off and running.” Conference organizer Julia Kaganskiy of New York’s Arts, Culture, and Technology Meet Up curated SMartCAMP’s program and a former actor, Danika Druttman, handled communications for the event.

In other words, from the beginning SMartCAMP was about people, people who post, blog, tag, add, and tweet, but above all, people who meet and link up through quirky, often unpredictable, circumstances to pursue a shared idea. According to the speakers in SMartCAMP’s program, this is the kind of easy serendipity that gives social networks their authenticity and value. While these qualities can’t quite be summoned, they can be encouraged and directed. For artists and administrators, the question is how to sustain these connections to build audience and patron loyalty. Whether you like the idea of artists taking on their own distribution, or whether you find it somehow uncomfortable, social media is influential and growing. As more than one person pointed out, social networking has surpassed pornography as the number one activity on the web.

Mark Schiller’s keynote opened the Saturday session. Well-known in the New York arts community, Schiller is the founder of The Wooster Collective, a public arts site that documents street art from around the world. Like many successful online projects, Wooster Collective began accidentally. Out walking his dog in his downtown neighborhood, Schiller began photographing street art, which he then posted online, forwarding the link to friends, and asking for their reactions. Soon his web page was managing hundreds of photos, receiving thousands of hits per day, and turning artists into online celebrities. Two Wooster Collective discoveries that have gone viral are Josh Harris, famous for his subway grate inflatable dog, and Jan Vorman, an artist who uses Lego bricks to patch crumbling city walls. Today, after eight years of posts, The Wooster Collective is the online authority on street art. Schiller receives a self-sustaining five hundred emails a day from artists who have done work, or have seen work, and would like to contribute. Wooster Collective also has a YouTube channel and a Twitter feed.

In many ways Wooster’s success seems unpredictable and non-reproducible, a fad, some kind of dumb luck. Yet, in retrospect, Schiller is able to point out specific qualities that made the site popular. First, there was page rank. Since no one was writing about street art in any other media, Wooster Collective’s art tags quickly went to the top of the search engine indexes. This kind of self-reinforcing rank allowed Schiller’s blog to get more traffic and, consequently, to pull more traffic from user searches. Second, ninety percent of the content on The Wooster Collective was original, making Schiller’s blog a feeder for other arts pages, increasing its incoming links and, again, boosting its reputation and its rank. Third, there are no ads at all on the Wooster site per se, mostly, Schiller says, because ads would be distracting both for him and his followers. Free from ads, Wooster Collective has no traffic stats to maintain, meaning Schiller is free to indulge himself in what his readers like best, Wooster’s own weird personality. On most days the site wavers slightly between media outlet and community bulletin board.

However, as important as his community may be, Schiller explained that Wooster readers are actually heavily restricted. The community is largely passive. Readers can email, but they can’t comment, upload, or see who else is online. Although some of site is user generated content, sites built on user content are notoriously second-hand and boring, so reader contributions are very heavily curated. The result is a blog that remains personal and interesting to all. Schiller also says audience building on the Wooster site has always been secondary to his main mission of sharing a passion for street art. According to Schiller, that passion is what works online and the effort to express it means a willingness to try anything. After all, Schiller reasons, “if you don’t like it, you can always stop. If a projects takes more than ten minutes to finish, stop. If it’s not fun, stop. If it’s not inspiring, stop.” Finding podcasts “not fun”, The Wooster Collective recently quit making them. They quit making mobile apps too. Schiller suspects that it is the resulting cheerfulness, lack of strain, exuberance, or even silliness, that connects an audience to a blog, a pursuit, or to an artist.

For Etsy, an online site where artists sell their work directly, community came first, web presence second. Anda Corrie, manager of Etsy’s Twitter feed, explains that Etsy was started at a time when the DIY arts culture was strong and growing, but artists still had few outlets for what they made. Etsy was one of the first sites to give them that outlet and, for a small commission, the site benefited greatly from its fortunate timing. Still, there is a balance between artist and audience that sustains Etsy and makes it work. In addition to responding to community needs, Corrie notes that the governance of sites like Etsy should be as transparent as possible. She reminds media managers rushing to reach out to remember to build a way for their readers and followers to reach in. Etsy uses a community council model. Councils change monthly, giving suggestions for improvements to the site and its forums. This is a time consuming model to attempt but, like Schiller, Corrie feels media planners who go through the motions without really getting involved are unlikely to succeed.

Michelle Shildkret, who represented Cake Group would say that you can’t fake what you are online, just as you can’t hire someone to “make you go viral”. She advises artists to slow down, figure out who to reach out to, where they are online, what they do when they’re online, and how someone might get their attention. When you can answer those questions, you’re ready to approach a social media plan. Shildkret also believes that a small, engaged community may be better than thousands and thousands of disinterested friends. Choose to introduce yourself and your work to places you like, make a difference there first, then advance slowly. John Birdsong of Panman Productions says artists often need to open up in exchange for popular attention. Birdsong endorses the strategy of a behind the scenes look at a studio or art process by posting “making of” videos to UStream or YouTube. These sentiments were echoed by others. Natasha Wescoat, a writer for EBSQ, the self-represented artist’s blog, became obsessed with eBay auctions as a community college student. Wescoat noticed that what honestly attracted her to an artist’s online profile was not necessarily the work. As an audience member, she also wanted personality, a connection, and some sense that there was a real person behind the presentation. Where Schiller describes a community that grows out of a shared passion, Wescoat sees community as a group centered on personality. Like Schiller, she encourages artists to try all ideas, continue with what feels right, and allow a web identity to evolve over time. For example, Wescoat describes her own online identity as an arc with three phases: experimentation, where she tried different approaches to making and selling work; narcissism, where she spent a good deal of time showing how the work was made; and establishment, where the size of her online audience is large enough to attract commissions from corporations and collectors.

Sharpie sketch queen and self-described “art school drop out” Molly Crabapple credits her web personality as fundamental to a full-time practice that draws commissions from the New York Times and Marvel Comics. Founder of Dr. Sketchy’s Anti-Art School, Crabapple introduced her online persona by compulsively posting to LiveJournal. Today, her favorite platform is Twitter and her media tool of choice is the one hundred and forty character tweet. Crabapple likes Twitter’s immediacy and tweets to get illustration suggestions from her followers, to find emergency crash spaces, and to “manifest” anything. She advises underrepresented artists to do whatever it takes to build a following online: friend friends of friends, promise to perform humiliating stunts for your followers, tweet about everything you do, reward your one hundredth or one thousandth follower with some kind of gift, a sketch or drawing, for instance. When the earthquake struck Haiti, Crabapple tweeted for drawing suggestions, drew those suggestions live online, then auctioned those drawings off in a benefit for Doctors without Borders. Yancey Strickler who co-founded the microfunding platform Kickstarter goes a step further. Kickstarter allows artists to post projects online and request small funding pledges from their followers. These pledges remain virtual until the project pledges reach full funding. At that point, sponsors pay up, the project is funded, and Kickstarter receives five percent of the amount raised. But pledge money is not always a reflection of your project pitch, Strickler points out, saying that what succeeds online is a good narrative and a connection with the audience that feels authentic. According to Strickler, people on Kickstarter are only somewhat concerned with the quality or originality of the work in front of them. More often, their decision to contribute to an artist’s goal proceeds along the lines of questions like “Do I like this person?” or “Could I be friends with this person?”.

If all this sounds a bit disingenuous or self-serving, remember that social media connects artists and audiences directly and that this connection now has its own considerations. There are some dangers in its manipulation, but the benefits need to be recognized. Adam Smith of Dance Theater Workshop’s and the New York branch of the Neo-Futurists uses blogging and community choreography as forms of outreach. While there are no hard numbers for increases in audience through the blog, DTW’s paid audience has gone from sixty to eighty percent of the house. Working on getting the tools right isn’t necessarily a negative and will probably take some work. Dancer Lisa Niedermeyer says: “You can’t just be clever, you have to be smart, and that none of this has been around long enough for any of us to be wise (yet). That any one experiment can be clever, and with speed and easy access can go live, but it takes being smart for it to be sustainable.”

Niedermeyer works on Virtual Pillow, the tech initiative of Jacob’s Pillow Dance. In some ways Niedermeyer considers the company’s online presence a fourth stage: “A global, interactive space serving a virtual community that might not ever be able to physically visit us in the Berkshires of Massachusetts, but highly value our archives, performances, professional school, creative development residency programs, etc.”

A second part of Virtual Pillow’s mission is to bring the work of the company, including its history, to a wider audience via social media, streaming sites, or any other online platform. Niedermeyer attended SMartCAMP for the chance to hear other institutions and artists discuss what worked and what did not. She says the conference gave her more perspective on the strategies available to Virtual Pillow: “I felt that the conference speakers and participants were really talking about the big picture, big ideas. Gravity Rail, for example, with their passion to explode open and transform eCommerce models for artists.”

Performers are not alone in the need to link up. According to Nancy Proctor, the museum is a distributed network whether curators accept that idea or not, and agile use of social media is essential to responsive curation. Proctor heads New Media at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, a museum which now gets more visitors online than in person. Are those online visitors any less real? Should their visit be any less satisfying? Should their use of the museum be any less respected? Noting that desktop activities are increasingly moving to the mobile web, Proctor urges curators to meet visitors where they are through sms, tweets, and mobile applications.

Examples of another kind of user centered curation came from Titus Bicknell, founder of pinkink, who believes audiences and their questions now lie at the center of any program strategy. Bicknell’s examples of user centered curation included a podcast that asks visitors to enter a space, look at the art, and record any questions they might have. In this curation model, socially aware programmers ask audiences what they would like to know, rather than telling audiences what it is believed they should know. Allegra Burnette, Creative Director of Digital Media at MoMA, pointed out excellence in web presence like the Indianapolis Museum of Art’s fine arts blog ArtBabble, but added that MoMA uses Twitter feeds specifically to talk about current exhibitions at home and elsewhere. MOMA also offers podcasts on iTunesU where, Burnette says, downloads have increased about ten times this year. More and more, curation extends beyond the exhibit to the conversation about that exhibition, a conversation that defines your institution on the social web through bookmarking, favoriting, collecting, sharing, recommending, and searching. Like the Wooster Collective’s Schiller, Burnett advises media managers to avoid blatant marketing and to discuss events of interest to readers whether those events are part of a home exhibition or are occurring elsewhere.

Even in competition with Arts Week, SMartCAMP sold out. In addition to a long list of good speakers, there was a great deal of conversation and connection going on across the seats, in the halls, throughout the lobby and meeting rooms, and at the bar. Absolutely no one was asked to turn off a cell phone. Executive producer Matt Semler says: “We trended on Twitter both days and ended up with 120,000 individual views on UStream. The audience was very nicely mixed. While we don’t have any specific data on demographics my impression was that the room was evenly split between art executives and artists.”

In April, Semler and Roger Smith Arts will present a cello performance by Peter Gregson from within a Morgan O’Hara installation inside The LAB gallery space in New York. As Gregson plays, O’Hara will perform one of her “Live Transmissions” of Peter’s performance. The event will be streamed live over UStream and, as with all LAB performances, will be viewable from the street as well.

Data Soliloquies

Richard Hamblyn and Martin John Callanan

London: Slade Press, 2009

112 pages

ISBN 978-0903305044

Featured image: Data Soliloquies is a book about the extraordinary cultural fluidity of scientific data