Jonas Lund’s artistic practice revolves around the mechanisms that constitute contemporary art production, its market and the established ‘art worlds’. Using a wide variety of media, combining software-based works with performance, installation, video, photography and sculptures, he produces works that have an underlying foundation in writing code. By approaching art world systems from a programmatic point of view, the work engages through a criticality largely informed by algorithms and ‘big data’.

It’s been just over a year since Lund began his projects that attempt to redefine the commercial art world, because according to him, ‘the art market is, compared to other markets, largely unregulated, the sales are at the whim of collectors and the price points follows an odd combination of demand, supply and peer inspired hype’. Starting with The Paintshop.biz (2012) that showed the effects of collaborative efforts and ranking algorithms, the projects moved closer and closer to reveal the mechanisms that constitute contemporary art production, its market and the creation of an established ‘art world’. Its current peak was the solo exhibition The Fear Of Missing Out, presented at MAMA in Rotterdam.

Annet Dekker: The Fear Of Missing Out (FOMO) proposes that it is possible to be one step ahead of the art world by using well-crafted algorithms and computational logic. Can you explain how this works?

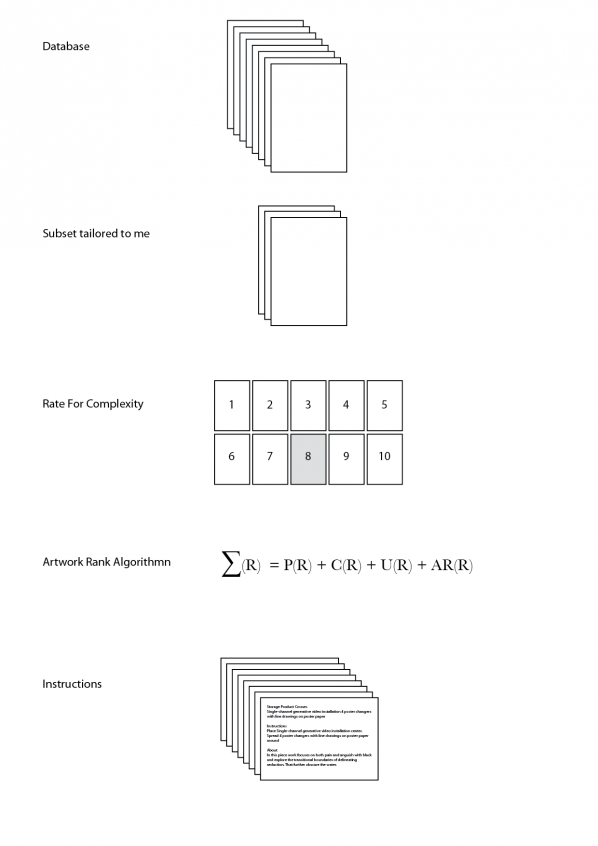

Jonas Lund The underlying motivation for the work is treating art worlds as networked based systems. The exhibition The Fear Of Missing Out spawned from my previous work The Top 100 Highest Ranked Curators In The World, for which I assembled a comprehensive database on the bigger parts of the art world using sources such as Artfacts, Mutaul Art, Artsy and e-flux. The database consists of artists, curators, exhibitions, galleries, institutions, art works and auction results. At the moment it has over four million rows of information. With this amount of information – ‘big data’ – the database has the potential to reveal the hidden and unfamiliar behaviour of the art world by exploring the art world as any other network of connected nodes, as a systemic solution to problematics of abstraction.

In The Top 100 Highest Ranked Curators In The World, first exhibited at Tent in Rotterdam, I wrote a curatorial ranking algorithm and used the database, to examine the underlying stratified network of artists and curators within art institutions and exhibition making: the algorithm determined who were among the most important and influential players in the art world. Presented as a photographic series of portraits, the work functions both as a summary of the increasingly important role of the curator in exhibition making, as an introduction to the larger art world database and as a guide for young up and coming artists for who to look out for at the openings.

Central to the art world network of different players lies arts production, this is where FOMO comes is. In FOMO, I used the same database as the basis for an algorithm that generated instructions for producing the most optimal artworks for the size of the Showroom MAMA exhibition space in Rotterdam while taking into account the allotted production budget. Prints, sculptures, installations and photographs were all produced at the whim of the given instructions. The algorithm used meta- data from over one hundred thousand art works and ranked them based on complexity. A subset of these art works were then used, based on the premise that a successful work of art has a high price, high aesthetic value but low production cost and complexity, to create instructions deciding title, material, dimensions, price, colour palette and position within the exhibition space.

Similar to how we’re becoming puppets to the big data social media companies, so I became a slave of the instructions and executed them without hesitation. FOMO proposes that it is possible to be one step ahead of the art world by using well-crafted algorithms and computational logic and questions notions of authenticity and authorship.

AD: To briefly go into one of the works, in an interview you mention Shield Whitechapel Isn’t Scoop – a rope stretched vertically from ceiling to floor and printed with red and yellow ink – as a ‘really great piece’, can you elaborate a little bit? Why is this to you a great piece, which, according to your statement in the same interview, you would not have made if it weren’t the outcome of your analysis?

JL: Coming from a ‘net art’ background, most of the previous works I have made can be simplified and summarised in a couple of sentences in how they work and operate. Obviously this doesn’t exclude further conversation or discourse, but I feel that there is a specificity of working and making with code that is pretty far from let’s say, abstract paintings. Since the execution of each piece is based on the instructions generated by the algorithm the results can be very surprising.

The rope piece to me was striking because as soon as I saw it in finished form, I was attracted to it, but I couldn’t directly explain why. Rather than just being a cold-hearted production assistant performing the instructions, the rope piece offered a surprise aha moment, where once it was finished I could see an array of possibilities and interpretations for the piece. Was the aha moment because of its aesthetic value or rather for the symbolism of climbing the rope higher, as a sort of contemporary art response to ‘We Started From The Bottom Now We’re Here’. My surprise and affection for the piece functions as a counterweight to the notion of objective cold big data. Sometimes you just have to trust the instructionally inspired artistic instinct and roll with it, so I guess in that way maybe now it is not that different from let’s say, abstract painting.

AD: I can imagine quite a few people would be interested in using this type of predictive computation. But since you’re basing yourself on existing data in what way does it predict the future, is it not more a confirmation of the present?

JL: One of the only ways we have in order to make predictions is by looking at the past. Through detecting certain patterns and movements it is possible to glean what will happen next. Very simplified, say that artist A was part of exhibition A at institution A working with curator A in 2012 and then in 2014 part of exhibition B at institution B working with curator A. Then say that artist B participates in exhibition B in 2013 working with curator A at institution A, based on this simplified pattern analysis, artist B would participate in exhibition C at institution B working with curator A. Simple right?

AD: In the press release it states that you worked closely with Showroom MAMA’s curator Gerben Willers. How did that relation give shape or influenced the outcome? And in what way has he, as a curator, influenced the project?

JL: We first started having a conversation about doing a show in the Summer of 2012, and for the following year we met up a couple of times and discussed what would be an interesting and fitting show for MAMA. In the beginning of 2013 I started working with art world databases, Gerben and I were making our own top lists and speculative exhibitions for the future. Indirectly, the conversations led to the FOMO exhibition. During the two production phases, Gerben and his team were immensely helpful in executing the instructions.

AD: Notion of authorship and originality have been contested over the years, and within digital and networked – especially open source – practices they underwent a real transformation in which it has been argued that authorship and originality still exist but are differently defined. How do see authorship and originality in relation to your work, i.e. where do they reside; is it the writing of the code, the translation of the results, the making and exhibiting of the works, or the documentation of them?

JL: I think it depends on what work we are discussing, but in relation to FOMO I see the whole piece, from start to finish as the residing place of the work. It is not the first time someone makes works based on instructions, for example Sol LeWitt, nor the first time someone uses optimisation ideas or ‘most cliché’ art works as a subject. However, this might be first time someone has done it in the way I did with FOMO, so the whole package becomes the piece. The database, the algorithm, the instructions, the execution, the production and the documentation and the presentation of the ideas. That is not to say I claim any type of ownership or copyright of these ideas or approaches, but maybe I should.

AD: Perhaps I can also rephrase my earlier question regarding the role of the curator: in what way do you think the ‘physical’ curator or artist influences the kind of artworks that come out? In other words, earlier instructions based artworks, like indeed Sol LeWitt’s artworks, were very calculated, there was little left to the imagination of the next ‘executor’. Looking into the future, what would be a remake of FOMO: would someone execute again the algorithms or try to remake the objects that you created (from the algorithm)?

JL: In the case with FOMO the instructions are not specific but rather points out materials, and how to roughly put it together by position and dimensions, so most of the work is left up to the executor of said instructions. It would not make any sense to re-use these instructions as they were specifically tailored towards me exhibiting at Showroom MAMA in September/October 2013, so in contrast to LeWitt’s instructions, what is left and can travel on, besides the executions, is the way the instructions were constructed by the algorithm.

AD: Your project could easily be discarded as confirming instead of critiquing the established art world – this is reinforced since you recently attached yourself to a commercial gallery. In what way is a political statement important to you, or not? And how is that (or not) manifested most prominently?

JL: I don’t think the critique of the art world is necessarily coming from me. It seems like that is how what I’m doing is naturally interpreted. I’m showing correlations between materials and people, I’ve never made any statement about why those correlations exist or judging the fact that those correlations exist at all. I recently tweeted, ‘There are three types of lies: lies, damned lies and Big Data’, anachronistically paraphrasing Mark Twain’s distrust for the establishment and the reliance on numbers for making informed decisions (my addition to his quote). Big data, algorithms, quantification, optimisation… It is one way of looking at things and people; right now it seems to be the dominant way people want to look at the world. When you see that something deemed so mysterious as the art world or art in general has some type of structural logic or pattern behind it, any critical person would wonder about the causality of that structure, I guess that is why it is naturally interpreted as an institutional critique. So, by exploring the art world, the market and art production through the lens of algorithms and big data I aim to question the way we operate within these systems and what effects and affects this has on art, and perhaps even propose a better system.

AD: How did people react to the project? What (if any) reactions did you receive from the traditional artworld on the project?

JL: Most interesting reactions usually take place on the comment sections of a couple of websites that published the piece, in particular Huffington Post’s article ‘Controversial New Project Uses Algorithm To Predict Art’. Some of my favourite responses are:

‘i guess my tax dollars are going to pay this persons living wages?’

‘Pure B.S. ……..when everything is art then there is no art’

‘As an artist – I have no words for this.’

‘Sounds like a great way to sacrifice your integrity.’

‘Wanna bet this genius is under 30 and has never heard of algorithmic composition or applying stochastic techniques to art production?’

‘Or, for a fun change of pace, you could try doing something because you have a real talent for it, on your own.’

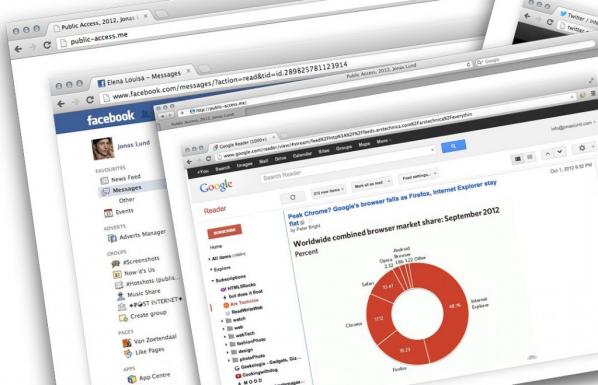

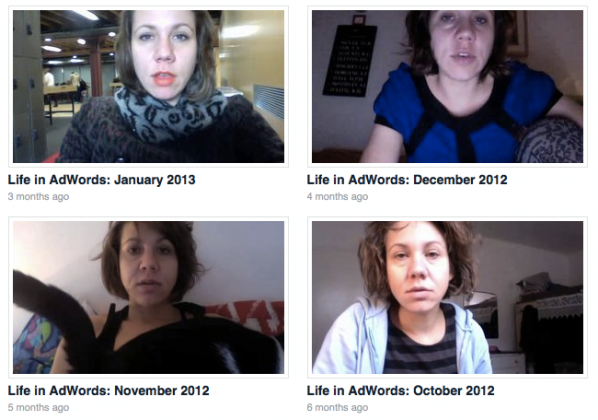

AD: Even though the project is very computational driven, as you explain the human aspects is just as important. A relation to performance art seems obvious, something that is also present in some of your other works most notably Selfsurfing (2012) where people over a 24 hour period could watch you browsing the World Wide Web, and Public Access Me (2013), an extension of Selfsurfing where people when logged in could see all your online ‘traffic’. A project that recalls earlier projects like Eva & Franco Mattes’ Life Sharing (2000). In what way does your project add to this and/or other examples from the past?

JL: Web technology changes rapidly and what is possible today wasn’t possible last year and while most art forms are rather static and change slowly, net art in particular has a context that’s changing on a weekly basis, whether there is a new service popping up changing how we communicate with each other or a revaluation that the NSA or GCHQ has been listening in on even more facets of our personal lives. As the web changes, we change how we relate to it and operate within it. Public Access Me and Selfsufing are looking at a very specific place within our browsing behaviour and breaks out of the predefined format that has been made up for us.

There are many works within this category of privacy sharing, from Kyle McDonalds’ live tweeter, to Johannes P Osterhoff’s iPhone Live and Eva & Franco Mattes’ earlier work as you mentioned. While I cannot speak for the others, I interpret it as an exploration of a similar idea where you open up a private part of your daily routine to re-evaluate what is private, what privacy means, how we are effected by surrendering it and maybe even simultaneously trying to retain or maintain some sense of intimacy. Post-Snowden, I think this is something we will see a lot more of in various forms.

AD: Is your new piece Disassociated Press, following the 1970s algorithm that generated text based on existing texts, a next step in this process? Why is this specific algorithm of the 70s important now?

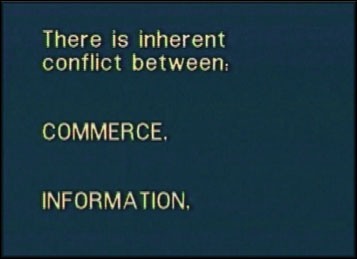

JL: Central to the art world lies e-flux, the hugely popular art newsletter where a post can cost up to one thousand dollars. While spending your institution’s money you better sound really smart and using a highly complicated language helps. Through the course of thousands of press releases, exhibition descriptions, artist proposals and curatorial statements a typical art language has emerged. This language functions as a way to keep outsiders out, but also as a justification for everything that is art.

Disassociated Press is partly using the Dissociated Press algorithm developed in 1972, first associated with the Emacs implementation. By choosing a n-gram of predefined length and consequently looking for occurrences of these words within the n-gram in a body of text, new text is generated that at first sight seems to belong together but doesn’t really convey a message beyond its own creation. It is a summary of the current situation of press releases in the international English art language perhaps, as a press release in its purest form. So, Disassociated Press creates new press releases to highlight the absurdity in how we talk and write about art. If a scrambled press release sounds just like normal art talk then clearly something is wrong, right?

Eva Kekou met Tobias Rosenberger at the international e-MobiLArt workshop which took place in Athens, Vienna and Rovaniemi, in turn these led to a number of exhibitions and successful collaborations between artists and theorists. She now invites him to discuss his work, issues of surveillance and how a young European artist views the situation in China and what he expects from his interaction with the Chinese art scene.

Tobias Rosenberger (b. 1980) is a German media artist who works at the crossroads of media art, visual arts, and performance. He has produced art works in Yemen, Spain, Mexico, India, and Ukraine etc. Since 2011 he has been based in China, where he teaches at the College of New Media Art, Shanghai Institute of Visual Art.

“Nowadays, anyone who wants to combat lies and ignorance and to write the truth must overcome at least five difficulties. He must have the courage to write the truth when it is suppressed everywhere; the wisdom to recognize it, although it is concealed everywhere; the skill to use it as a weapon; the judgment to choose those in whose hands it will be effective; and the cunning to spread the truth among such people.” (Bertolt Brecht)

Eva Kekou: I would like to start this interview with this quote which seems to be significant for your work and in particular the recent one – the secret race film and discussion at Goethe Institut Washington. As you well state in your event invite: “It was pure coincidence that for a few days in the summer of 2013, two unrelated events simultaneously dominated the major headlines in the German press: the monitoring and spying scandal of 2013, triggered by Edward Snowden’s leaks of National Security Agency top-secret classified documents, and the official acknowledgement of the prevalence of doping in competitive sports, best symbolized by Lance Armstrong’s televised confession.” What is the significance of surveillance in a globalized social and political context and where is the place of art within it? There are obvious reasons you decided to launch this in Washington through Goethe but I would like you to comment on this.

Tobias Rosenberger: Surveillance and espionage are as old as civilization. Power was always constructed, maintained, and expanded through monitoring, categorising, repressing, and excluding people. We all know that the digital apparatus opens a new world of possibilities to organize, quantify and control life and society in a before unknown scale, speed and efficiency. While I agree that we need early warning models to anticipate and fight cruelty and injustice whenever possible, I don’t believe that we can draw a sharp border between an evil surveillance that fuels unfair and inhuman systems and a necessary one that pretends to save dignity and a lawful order. The challenges of our time can no longer be met by elitism and secretiveness, but require the joint efforts from the middle of society. An independent art that rejects the simple desire for (self-)confirmation does not only open a non-biased discursive space for critical reflection, but it also has the potential to demask and break the mechanisms of power, as long as it takes its audience seriously. But to be able to do so, art also has to find its audience.

EK: It occurs to me that place and space play a very important role in your work and inspiration. How do these relate with each other with pieces of your work in a globalized and mobile network underlined by politics?

TR: I have a very pragmatic approach to what I am trying to do: Not following a specific agenda and always staying as curious and open as possible. This requires both a certain naivety and an observing attitude. I never start an artistic process with a specific idea or question, but i get attracted by places and spaces that i try to discover without too much of my personal baggage. But since space and place are never abstract but segmented by politics both on macro and micro layers, the resulting works often deal with political questions.

EK: How did you become interested in China and what do you find fascinating or difficult working there? Is it interesting for you as a European?

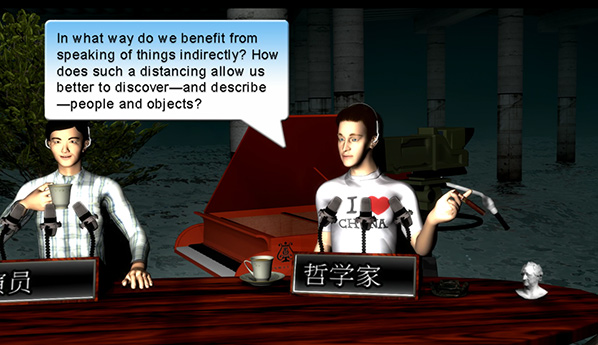

TR: I have a very special relationship to China. With my Chinese wife I decided three years ago to move there and to found a family. I was always fascinated by China as a cultural space, with a tradition of art and philosophy at least as long as in Europe. I also really like the food and the people there. As a foreigner I experience it as very fruitful to see things from a specific distance, both if I try to understand the culture, but also especially if I look back from there to where I come from. It is very interesting to observe the relation between art and politics, how the government here really appreciates art and how it is also afraid of it.

How artists, critics and curators fight for free space, a career, or both. In Shanghai you have both the global economy and the local life at your house-door. The country faces a lot of problems, and very often one can get the impression that things are not happening at all just because there is a small possibility that something unexpected could happen. So many people behave very pro-actively in a way that they won’t run into any problems themselves. But this maxim “to have everything running smooth” you certainly don’t only encounter in China.

EK: Referring to some of your recent works (installation and performance): Choose any you like… How do you reach out to audiences and what is the main aim in your own work?

TR: “The First Twenty Years” is an installation that was shown in two different versions at the end of 2012 in Kiev and Dnipropetrovsk. I developed the basic idea for that work in 2011, when I was invited to spend some time in a small Ukrainian village near Kiev at a private artist residency programme. During that time the nation celebrated the 20th anniversary of its independence. There was a strange, partly paralyzed mood. But I also witnessed very controversial discussions with artists, curators and critics, and a new generation that seemed not anymore willing to accept living in a nation that was more and more perceived as a prison. So when I was approached during that time to do a work based on my experiences in the Ukraine, I decided to base it on Xavier de Maistres “Journey around my room” and Schuberts Music, which was inspired by a poem by Christian Friedrich Daniel Schubart.

I didn’t intent to comment directly on the situation there, but rather was trying to understand for myself what was happening. For me, art is not about expression but about the creation of a space where everybody is invited to take a bit of distance so to be able discover something from different perspectives and to think in his/her own way.

Surveillance Cameras dancing to Schubert, on Vimeo

EK: Can you give us a bit more information about a project that you have described alsewhere in the following way: “Right now working on a light sculpture for permanent setup in a former WWII Top secret military site, where some crazy NS-Germany scientist wanted to invent an x-ray wonder-weapon to shoot planes and soldiers, this involves an always transforming multichannel-sound installation, motorized miniatures (arduino-controlled), 2 projectors and led-objects. I will make an extra independent video of this work, filmed with multiple moving surveillance cams.”?

TR: I was approached by a cultural initiative that runs today a small history museum in a former research bunker, which was secretly constructed in 1942 / 1943 underneath a camouflage building. I came across a letter in which a certain Professor, Dr. Ernst Schiebold, proposed “An additional weapon to fight and eliminate the crews of hostile airplanes and ground troops in the defensive via x-ray and electron radiation”.

A weird ten pages male war fantasy about a new kind of tubular x-ray canon, written in a crude mixture of physical pseudo-science, soft patriotic enthusiasm and German pedantism. Schiebold really got his bunker built to start with his research. Everything was kept top secret, but stopped 18 months later without results. I decided to bring Schiebold’s proposal back into the space which only existed because of it: As a pure proposal, enhanced and communicated with new media technology.

A lot of the tools that we are using as new media artists exist mainly through military development. So my intention was also to give something back. The audience will listen to single sentences that are randomly taken out of Schiebold’s letter and re-arranged into a constantly transforming synthetic sound atmosphere, which is synchronized with light beams crossing a motorized miniature military model. The toy miniatures cast shadows of moving soldiers and airplanes onto the walls. LED lights are flashing out of a tubular manhole, which was originally constructed to be used with a Betatron. All the technology that I use is quite low-budget and geeky. Last week I started to install the parts on site, and I have to admit that it is also a very weird experience for me to spend nights working alone in a former military research bunker, climbing down in a manhole and setting up the mockup of a “super-weapon” people researched in the darkest years of German history. Sure I will also try to document it properly.

EK: Do you think art can be global and political, if not, what are the main restrictions we are all subjected to? How can art and artists make a difference in this respect?

TR: I think that art is per se political, since it deals with and also influences our perception of reality. And while all our lives are clearly connected in a global economy of good and information-exchange, art does also always operate on a global scale. As an artist I believe that it is worth to be curious and to investigate the (media) apparatuses and dispositifs that surround us, to take them apart and re-design them. What are they good for, what effects do they cause? While the world is getting closer, the world is never the same – people have different histories, problems, possibilities and hopes. As Europeans we take many things for granted, that other people see differently – or vice versa. I think artists can always make a difference, as long as they stay independent and continue to tackle serious questions, but don’t take themselves too seriously while doing so. We should laugh more together.

EK: What are your future aims and plans?

TR: I am looking forward to the new semester in Shanghai, where I will mentor the graduate works of eight students. I will also collaborate with Chinese artist Mujin (Lixin Bao) – a fellow teacher at the Shanghai Institute of Visual Art – on a series of works exploring the notion of the “Chinese Dream” and its perception both nationally and globally. I guess this dialogue will become quite interesting.

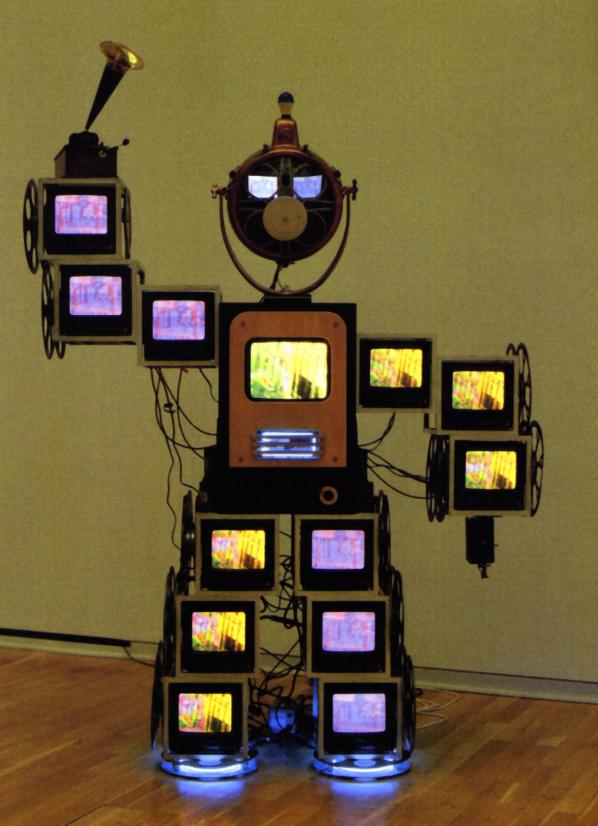

Featured image: Mari Velonaki, “The Woman and The Snowman”. Responsive installation incorporating autokinetic robotic sculpture (2013).

I first met Mari Velonaki in person a couple of years ago and since then have attended one of her lectures. I was impressed by her work as a cross-disciplinary arts-led researcher. Also, her imaginative approach in her art practice which spans across interactive installations, robotics and kinetic sculpture and human-robot interaction. This interview is an opportunity for readers to find out more about the ideas and the contexts behind her work, including plans, dreams and also what is happening in Sydney Australia, where she is based.

Eva Kekou: I am fascinated by the project Fish-Bird, it operates as a metaphor for me to connect and relate two different notions in the most poetic way as in the case of art, science and technology. Could you please give us some information about the idea of this project and both its artistic and research views – also how audiences responded to this.

Mari Velonaki: “Fish-Bird” is an interactive autokinetic artwork that investigates the dialogical possibilities between two robots, in the form of wheelchairs, that can communicate with each other and with their audience through the modalities of movement and written text. The chairs write intimate letters on the floor, impersonating two characters (Fish and Bird) who fall in love but cannot be together due to “technical” difficulties. This was an interdisciplinary project that involved the creation of novel interfaces for human-robot interaction, experimentation in distributed sensory systems and robot ‘perception’.

The wheelchair was chosen as the dominant object of the installation for several reasons. A wheelchair is the ultimate kinetic object, since it self-subverts its role as a static object by having wheels. At the same time, a wheelchair is an object that suggests interaction – movement of the wheelchair needs either the effort of the person who sits in it, or of the one who assists by pushing it. A wheelchair inevitably suggests the presence or the absence of a person.

Furthermore, the wheelchair was chosen because of its relationship to the human – it is designed to almost perfectly frame and support the human body, to assist its user to achieve physical tasks that they may otherwise be unable to perform. In a similar manner, the Fish-Bird project utilizes the wheelchairs as vehicles for communication between the two characters (Fish and Bird) and their visitors. Finally, the wheelchair also possesses an aesthetic that is very different from the popular idea of a robot, as it is neither anthropomorphic nor “cute”. Given that a wheelchair is a socially charged object, the interactive behaviour and the scripting of how the chair should move was developed in consultation with wheelchair users. The participants are actively discouraged from sitting on the wheelchairs: if a participant sits on a wheelchair a sensor embedded in the seat upholstery pauses the entire system until the participant vacates the wheelchair.

What we’ve learned from the Fish-Bird project in relation to human-robot interaction, after 35,000 recorded encounters in five countries, is that behaviour is more important than appearance. Although Fish and Bird have the utilitarian appearance of an assistive device, participants were drawn to them because of the way they move and interact physically with them, and because of the handwritten style ‘personal’ messages that they print for their audience.

EK: Your project Diamandini brings up issues of femininity, interactivity into the context of computer and informatics. It again works as a nice metaphor but in practice it is a research project between the Centre for Social Robotics, Australian Centre for Field Robotics, the University of Sydney and yourself. Can you give us more information about this and also report to us about the outcome of the research project about the understanding of the physicality that is possible and acceptable between a human and a robot within a social space.

MV: The original intent of the Diamandini project was to create a robot that was non-representational and non-anthropomorphic – also, I wanted to work with the concept of one-to-one interaction: one human, one kinetic agent. As I started experimenting with a variety of abstract sculptural forms, although interesting in shape and structure, I found it extremely difficult to assign behaviours to them that could lead to emotional activation of the spectator/participant. These considerations influenced my decision to create a humanoid robot. This was a challenging decision, especially when I had to decide how the robot should look. I didn’t want Diamandini to have a typical humanoid robot aesthetic. I began to think of Diamandini as a female sculpture. In my mind Diamandini had a diachronic face that spans between centuries, a style that could be reminiscent of post-World War II fashion influences, and at the same time with futuristic undertones. Diamandini is small – only 155 cm high. I wanted her figure to be small and slender so that people didn’t feel threatened by her when she ‘floats’ in the installation space. I wanted her to look youthful, but not like a child, and for her age not to be easily identifiable. Interestingly, in my mind she is between 20 to 35 years old. Because I am a woman, I feel more comfortable working with a female rather than a male representation.

In relation to people interacting with Diamandini in social spaces, we are still processing data collected from 3,682 interactions at the Victoria & Albert Museum in 2012. From these interactions what we know so far is that, although people would spend – on average – more than five minutes with her in the Medieval and Renaissance Galley, only 88 people embraced her or held her hand. It will be interesting to compare this result with new data coming from Diamandini’s current exhibition at FACT, Liverpool, where she is exhibited in a contemporary gallery setting.

EK: You are an artist and researcher. How do you think that these two relate to each other, give feedback to each other and can give a mutual input to your work? How connected are art and research in general?

MV: I see my work as practice-led research. I’m interested in developing and testing new concepts of what an artwork can be, in the same way as I’m having conceptual and aesthetic concerns of what a robot can be. Interactive media art has a long history of looking at sharing spaces with projected and kinetic characters. I’m interested in the brief moment when a spectator becomes a participant – conceptually and physically. This is where the core of my research lies.

EK: The female character and femininity plays a crucial role in your work. How can “fragile femininity” be embraced by science and technology and its connected artwork under the light of media art?

MV: I don’t perceive my work as fragile femininity – at least consciously. Many of my characters don’t have gender: for example Fish-Bird, Fragile Balances, Current State of Affairs. If a representation of gender is necessary – as in previous works that contain projected digital characters (Pin Cushion, Unstill Life, etc.) or is a humanoid robot – I choose to work with female forms as I am more comfortable to sculpt, script and create a kinetic language for a female representation. The element of fragility, though, is a thread that links many of my works. Anne-Marie Duguet wrote a wonderful essay “The Power of Vulnerability” about my work ‘Fragile Balances’ (2008) in which she writes “’A fragile balance’ could define all complex interactive processes that involve human intervention. Interactivity always extends to the limits of more than one language, more than one reality. It relies on operations of interpretation and coding that, as a matter of course, produce slips of meaning, simplifications and omissions which can undermine the effectiveness and reciprocity of exchange, and hinder the pleasure of transgression.”

EK: I know you have exhibited in different parts of the world – how do audiences respond to your work?

MV: I guess it depends on the work. In general I think maybe I could add that I think people are attracted to my work because – although it partially depends on complex technological systems – the work itself doesn’t look at all technological. I want to believe that my audiences are attracted to my ‘characters’ maybe because of the element of surprise: a porcelain-like sculpture that moves; wheelchairs that write love letters; wooden cubes that act as embodied avatars for robotic characters.

EK: What are your next steps as an academic, artist and researcher? Which of your dreams do you want to make true through your work (relating them to art, science and technology as another metaphor)?

MV: At the moment a lot of my focus is on growing and strengthening the Creative Robotics Lab (CRL) at NIEA. I founded CRL with an aspiration to build a cross-disciplinary experimental space for human-robot interaction research and interface design. At CRL people from different disciplines – arts, robotics, psychology, philosophy – work together because they believe that, to improve human-robot interaction, a cross-disciplinarily approach is not complementary but essential. CRL for me is a safe place for risk-taking.

Mari Velonaki has worked as an artist and researcher in the field of interactive installation art since 1997. Mari has created interactive installations that incorporate movement, speech, touch, breath, electrostatic charge, artificial vision and robotics. In 2003 Mari’s practice expanded to robotics, when she initiated and led a major Australian Research Council art/science research project ‘Fish–Bird’ (2004-2007) in collaboration with roboticists at the Australian Centre for Field Robotics (ACFR). In 2006 she co- founded, with David Rye, the Centre for Social Robotics at ACFR, a centre dedicated to inter-disciplinary research into human-robot interaction in spaces that incorporate the general public. In 2007 Mari was awarded an Australia Council for the Arts Visual Arts Fellowship. In 2009 she was awarded an Australia Research Council Fellowship (2009–2013) for the creation of a new robotic form. In 2011 she was appointed as an Associate Professor at the National Institute of Experimental Arts (NIEA) at the College of Fine Arts, The University of New South Wales, where in 2013 she founded the Creative Robotics Lab. Mari’s artworks have been widely exhibited internationally. http://mvstudio.org/

Tatiana Bazzichelli is a researcher, networker and curator, working in the field of hacktivism and net culture. She is part of the transmediale festival team in Berlin, where she develops the reSource for transmedial culture, an ongoing distributed project of networking and research within the transmediale festival. She received a Ph.D. in Information and Media Studies from Aarhus University (DK), conducting research on disruptive art practices in the business of social media (title: Networked Disruption: Rethinking Oppositions in Art, Hacktivism and the Business of Social Networking). Bazzichelli is also a Postdoc Researcher at the Centre for Digital Cultures /Leuphana University of Lüneburg (DE).

In light of absolute domination by market forces over all of our lives, and with the top-down orientated power systems’ bias towards business and the implementation of a consumer class. New ways of thinking around the problem is called for. There has been a dramatic shift of unethical companies such as BP funding art’s and technology projects, and mainstream museums and galleries in the UK. [1] Alongside this, those hoping to receive arts funding are told to be innovative and more entrepreneurial than they already are. What they really mean by ‘innovative and entrepreneurial’ is, get in line with the values of a corporate mentality, and not be contextual or critical in one’s art practice. This wholesale move towards business as it further dominates the content, ideas, societal context, and missions by artists and art collectives – is of deep concern for all who wish to explore freedoms of expression on their own terms and not inline with the state’s or a corporation’s set of diverting agendas.

Art activism in media art and transdiscilpnary arts culture has engaged with political and societal issues while under the gaze of neoliberalism quite successfully. However, what changes have occured that we can draw upon to say we have built real alternative values for others to work with? There are plenty of people from the dark side calling us to join them, like that eirie voice from the original Evil Dead movie.

I’m reminded of Thomas Frank’s insightful words in his article TED talks are lying to you, that those who urge us to “think different” almost never do so themselves. [2] And this is the nub, what will become us if we step over into their world and adapt our minds to their visions?

“To expect or even wish those who rule and those serving them to change, and challenge their own behaviours and seriously critique their own actions is as likely as winning the National Lottery, perhaps even less.” [3] (Garrett 2013)

So, this brings us Tatiana Bazzichelli who has been thinking about this stuff a lot. Her Proposition is that we need climb out of these oppositional loops in order to find different ways of being, and refocus on potential art strategies in relation to a broken economy. In her publication Networked Disruption: Rethinking Oppositions in Art, Hacktivism and the Business of Social Networking, Bazzichelli puts forward the notion of disruptive business and it “becomes a means for describing immanent practices of hackers, artists, networkers and entrepreneurs”, and sheds “light on two different but related critical scenes: that of Californian tech culture and that of European net culture – with a specific focus on their multiple approaches towards business and political antagonism.”

Marc Garrett: In your book you examine a breadth of disruptive practices of networked art and hacking culture in California and Europe. You propose your main objective is to rethink the meaning of critical practices in art, hacktivism and social networking, analyzing them through business instead of being in opposition to it.

Could you explain how this would change situations and what it would bring to artists exploring disruption as part of their practice, networked art culture and the wider community, and what this may look like?

Tatiana Bazzichelli: I will begin answering your question by adding another one: Why do we need to rethink artistic and hacktivist oppositions in the context of social media and after the emergence of Web 2.0? This question is at the core of my book, and also the main link that connects together my previous book, Networking: The Net as Artwork (2006), and the following ones centered on the concept of networked disruption and disrupting business.

The idea of conscious participation in media practices is central to analyse the evolution and transformation of the concept of “networking” in the age of social media. My reflections are the consequence of a process of direct involvement within the activist (or rather “artivist”) scene in Italy since the mid-90s, and furthermore, they are based on the analysis of a more international fieldwork of practices between the Europen tradition of netculture, and the development of cyberculture in California. Practically all my books are to be thought of as subjective, and as consequences of a personal experience which aims to create connections between very diverse fields of action, applying the idea of networking both in theory and practice, and as a methodology of writing.

Between the end of the 1990s and the early 2000s, many actions of media criticism were often very dialectical, and rooted on the idea of antagonism as radical opposition. I am for example thinking about what was (erroneously) called “the anti-globalization movement”, the protests in Seattle, Prague, Goteborg, Genoa, etc.: somehow it was easier to identify an “enemy”, for everyone to unite against the same power. Unfortunately this also meant that it was easier to identify the members of the movement(s) themselves, and many protests faced violent chains of repression by the authorities. In particular in Genoa, the Italian movement and its global counterparts were hit hard. My personal opinion is that the frontal opposition, the idea of assaulting the “red zone” during the protests, did not work at all: we basically played the game of the police. Without dismissing this experience, which was very important in itself and for the start of new activist projects, after Genoa 2001 I started searching for a new way of activism that was not black and white, and which would be harder to appropriate. This was also the reason why I started entering in contact with many projects in the queer, pink, and independent porn culture, which were combining ludic strategies and playful disruption beyond oppositional confrontation. I was trying to connect those to the concept of hacking – mixing the codes to create disturbance, to generate subliminal interventions, to give rise to paradoxes, fakes and pranks, as previous projects based on multiple identities, from Luther Blissett to Neoism and Monty Cantsin, had done before.

“In 1994, hundreds of European artists, activists and pranksters adopted and shared the same identity. They all called themselves Luther Blissett and set to raising hell in the cultural industry. It was a five year plan. They worked together to tell the world a great story, create a legend, give birth to a new kind of folk hero.” Luther Blissett.

But after 2004, which is also the time of the emergence of Web 2.0, the critical framework of art and hacktivism shifted: networking, a concept which had informed the Avant-garde since the 1960s, became a tool for a wider audience, and a pervasive business strategy. The ideas of openness, do it yourself, sharing, the “mottos” of the hacker culture in the 1990s, became the main rhetoric of the Web 2.0 companies based on the appropriation of “free culture”. This meant to me that also artistic and hacker practices needed to be recontextualised, since the concept of social networking became something completely different from its roots, and the business companies themselves were applying the concept of disruption as main business logic. Is it possible to oppose disruption with disruption?

In the era of immaterial economy and increasing flexibility, the act of responding with radical opposition no longer looks like an effective practice, since the risk is to simply feed the same machine replicating the capitalistic logic of competitiveness and power conflicts. In my opinion, and here I speak through my “artivist” experience, even the concept of the multitude as a model of resistance against the capitalist system – which runs at a theoretical level – is difficult to apply on a pragmatic level without having to recreate the traditional dynamics of the “power-contra power” conflict. The point is to try to figure out how to imagine new forms of participation that go beyond dualistic conflict – and that go beyond the creation of a hegemonic and holistic entity, although presented as a plural (the multitude, indeed). As a result, it is definitely necessary to reformulate the language, which enters the sphere of production and the political, as Paolo Virno states, but most of all, activists practices and critical strategies need to be rethought.

What my book Networked Disruption suggests is the act of performing within the capitalist framework, not against it, keeping the dialectic open through coexisting oppositions. The notion of disruptive business is useful for reflecting on different modalities of generating criticism, shedding light on contradictions and ambiguities both in capitalistic logics and in artistic and hacktivist strategies, while rethinking oppositional practices in the context of social networking. In this book the concept of the Art of Disrupting Business must be interpreted beyond categorical definitions, and as a new input for imagination. “Disruption” implies a multi-angled perspective and it is a two-way process, where business and the antagonism of business intertwine. Adopting a hacker’s strategy, hacktivists and artists take up the challenge of understanding how capitalism works, transforming it into a context for intervention and trying to alter business logics. Rethinking strategies and modalities of opposition implies that new forms of interventions and political awareness should be proposed without antagonising them, but rather by playing with them and disrupting them from the inside of the machine. The vision of a distributed network of practices, participations and relationships can only be fragmented, and based on multiple layers of imagination.

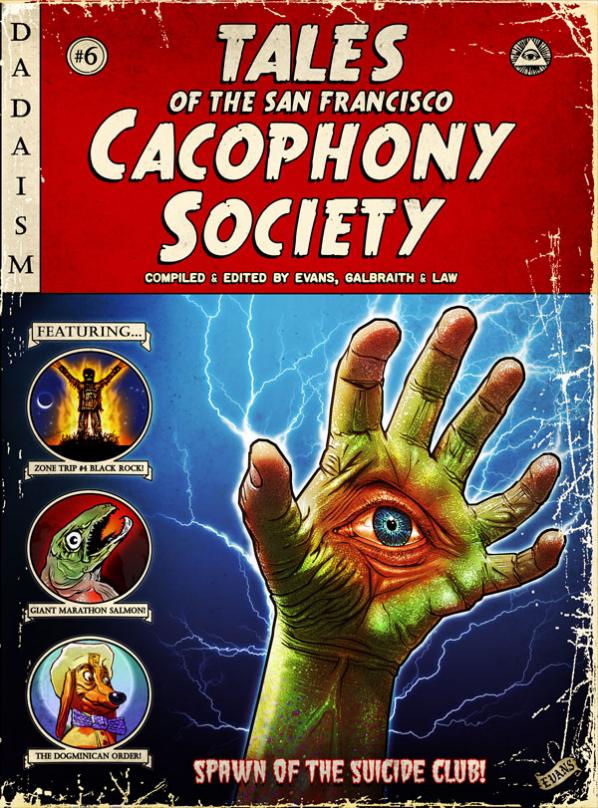

Today there are artists and activists who are inspired by a certain tradition of “disruption”, creating interventions from within, critically appropriating the business logics, stretching its limits, or proposing alternative models to it. Many of them are the case studies of my book, where I propose a constellation of social networking projects that challenge the notion of power and hegemony, and where social networking is not only technologically determined. Projects and experiences such as mail art, Neoism, The Church of the SubGenius, Luther Blissett, Anonymous, Anna Adamolo, Les Liens Invisibles, the Telekommunisten collective, The San Francisco Suicide Club, The Cacophony Society, the early Burning Man Festival, the NoiseBridge hackerspace, and many others. Of course there are many more of these. Holes in the system are everywhere, ready to be performed and disrupted.

MG: There is a quote in the book that it says, “Innovation is rooted in Desire, not need. Desire is the motivation for behaviour. Desire leads to goals, and goals lead to motivation, the internal condition that gives rise to what we want to do, based on our goals, what can we do – based on the norms of behaviour – and what we will do – the actions that we voluntarily decide to undertake. Motivation is the ethos of goal-oriented behaviour, and a company’s ability to understand motivation directly contributes to the success of their products and services in the marketplace” (Manu, 2010, p. 3).

I’m wondering, coming from an activist background myself where do you think free culture fits into this dialogue, especially in respect as a critique of products and services in the marketplace, as well as social forms of emancipation?

TB: The quote you are referring to comes from a book entitled Disrupting Business: Desire, Innovation and the Re-design of Business (Alexander Manu, 2010). As we can read in the business literature, the concept of disruptive business is rooted in the idea of disruptive innovation. Disruptive innovation, a term coined in 1997 by Clayton Christensen, Professor at the Harvard Business School, is used in business contexts to describe innovations that introduces a product or service in ways that the market does not expect. In the business culture, disruption not only means rupture, but links to the idea of innovation and re-design of behavioural tendencies. Therefore performing disruption shows a process that interferes with business, whilst at the same time generating new forms of business. This mutual feedback loop is at the core of my analysis.

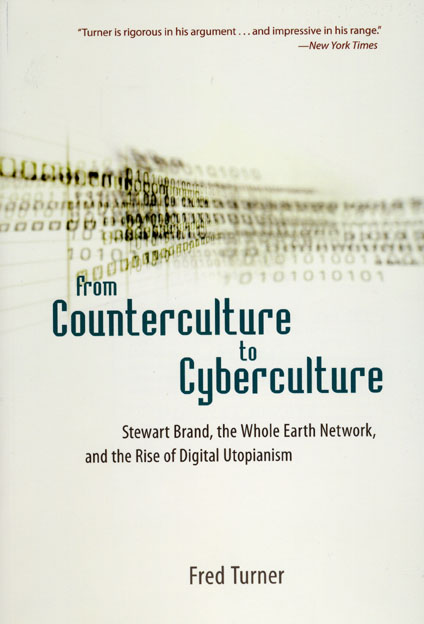

However in my book business is neither analysed through classical business school methodologies, nor seen as positive or negative, but it is a means for working consciously on political practices – and for raising questions on art and media criticism. In 2009 I was a visiting scholar at Stanford University where I was researching the reasons of the progressive commercialisation of networking contexts after the emergence of Web 2.0, through the development of hacker culture in the Silicon Valley. From the interviews that I conducted, and also via the close reading of the book From Counterculture to Cyberculture by Fred Turner, it was evident that since the development of the early cyberculture hackers and members of the so-called “counterculture” have been trying to disrupt business via their practices, and in parallel, business corporations have been trying to do the same through technological innovation. Since the 1960´s, hackers and artists in California have been active agents in business innovation while at the same time also undermining business. This is also very evident today in the business context of Web 2.0 where many hackers are working at the core of business, while disrupting it – the Anonymous entity is one of the most successful examples of this.

In my book I compare what the concept of business disruption meant in the European context and in the US, especially in Silicon Valley. When I was interviewing computer engineer Lee Felsenstein he told me that in California hackers would refuse hegemony but not business. This is also why many of them have no problem in working for Google, which is actually employing the best hackers of the area. In Italy we always claimed that hacking is politics, and politics is an “attitude”, which informs your everyday life and lifestyle. What I discovered in the Silicon Valley is that libertarian practices are often linked with the refusal of the political, and this is the position of many members of the hacker culture in California. Therefore, what for me was the initial “problem”, the contamination of business and free culture, was not considered as such among the hackers that I met between San Francisco and Palo Alto.

This consideration leads me to create a model of analysis named the “disruptive feedback loop”, based on the idea of layering instead of cooptation – such an idea of “layering” rather than cooptation, was proposed by Fred Turner in the lecture “The Bohemian Factory: Burning Man, Google and the Countercultural Ethos of New Media Manufacturing” (2009), while discussing the social phenomenon of Burning Man. The idea of the “mutual feedback loop” between business and hacker culture is instead the result of a conversation in 2009 with Jacob Appelbaum, who at the time was an active member of NoiseBridge in San Francisco, when we were reflecting on the development of hacker spaces in California. In my disruptive loop model, artists and hackers use disruptive techniques of networking in the framework of social media and web-based services to generate new modalities for using technology, which, in some cases, are unpredictable and critical; business enterprises apply disruption as a form of innovation to create new markets and network values, which are also often unpredictable. Networked disruption is a place where the oppositions coexist, and it is a reconfiguration of practices into a structure of mutual feedback instead of opposition.

Here I propose disrupting business as an art practice: artists and hackers adopt viral and flexible strategies, as does contemporary networking business, and by provoking contradictions, paradoxes and incongruities, business logic is détourned. This model can be applied both in the analysis of business contexts of social networking and of critical practices generated by hackers and artists. For example, projects such as Anna Adamolo and Seppukoo reflect on the tensions between the open and closed nature of social media, stressing the limits of Facebook’s platform, and working on unpredictable consequences generated by a disruptive use of it. Paradoxically, to be critical of business we should learn from it.

The Telekommunisten collective explains this well, and it is not a coincidence that Dmytri Kleiner comes from a Neoist background: the experiences of Luther Blissett and Neoism made it hard to see any “truth”, they forced us to question and examine our identities. If you claim to have the truth, you will fail – someone else will proclaim the truth, and perhaps with much more strength and power than you. The Miscommunication Technologies by the Telekommunisten show that the enemy can eat you up and that the capitalist system has endlessly more resources to force its “truth” on you. We have to learn from business, understand how to be pervasive. My point is that we should stop looking for the enemy, because who is the enemy today when disruption and its opposition are feeding the same machine? The challenge is to unite where the system can’t get you, and you’re not playing into its hands, exposing contradictions, generating disturbance, to disrupt and perform the feedback loop at once. The challenge facing the art of disruptive business is to dissipate oppositions through a network of multiple, distributed, playful and disruptive practices.

MG: It was licensed under a peer Production License (http://p2pfoundation.net/Copyfarleft), similar to a Copyfarleft License (http://p2pfoundation.net/Peer_Production_License). Very different than a Creative Commons Licence, and drawn up by one of the artists you write about in the book Dmytri Kleiner. It feels relevant to be on the P2P Foundation wiki, however it would be useful know how it relates to the context of your publication?

TB: As it is stated on the P2P Foundation website, based on the text published in The Telekommunist Manifesto, “the Peer Production License is an example of the Copyfarleft type of license, in which only other commoners, cooperatives and nonprofits can share and re-use the material, but not commercial entities intent on making profit through the commons without explicit reciprocity”. The Peer Production License is a hack of the Creative Commons licenses. Where the Creative Commons is mostly used for sharing works non-commercially, the Peer Production License wants to contribute in expanding a non-capitalist economy, generating earnings that are shared equally. Commercial use is therefore encouraged for independent and collective/common-based users only, proposing a business logic that does not lead to a private appropriation of community-created value.

This logic is also at the core of the “Venture Communism” concept coined by Dmytri Kleiner in 2001, which proposes to allocate equally the collectively owned material wealth, and to create a peer-to-peer social commons as an alternative to venture capitalism.

I decided to release the Networked Disruption book under this license because I consider it a coherent intellectual gesture, and also a “business experiment”. From what Dmytri told me this is the first book released under this license after the Telekommunist Manifesto, and hopefully the use of such license, if increased, will be part of poking a small hole in the capitalist economy, generating value which is not going into few owners’ pockets, but is shared equally among the workers and producers. This is also the reason why all my publications exist both online and on paper and are freely downloadable from the web, because it would be contradictory to write about certain topics and then release my toughts under proprietary licenses. In this case, since the book is about disrupting business, I decided to apply a disrupting business license, and to my point of view this is what the Peer Production License is.

Conclusion:

Bazzichelli’s investigation is a timely and necessary critique on how to free up networked forms of freedom of expression and its varied practice. At first, I was suspicious. Indeed, in a later publication on the subject co-edited by Tatiana Bazzichelli & Geoff Cox, called Disrupting Business: Art and Activism in Times of Financial Crisis; “Bifo” Berardi, in his article EMPTINESS says “Business is, in my opinion, the most despicable word in the vocabulary. Well, I will try to express it better: the meaning and implications of the word ‘business’ in contemporary culture and daily life, and the positive emphasis placed on this term, are the most telling symptoms of the abysmal alienation of our time.” On this I agree.

We are all emersed in the sea of neoliberalism and we are struggling to keep our heads above the water at various levels. Some are aware of it and are not dealing with it, most are unconscious of it and are drowning in it, and then there are those actively awake and exploring different and innovative ways to survive and hack ‘around, in between and through’ this deep totalising ocean.

Whether we like it or not, business unfortunately is the dominating regime controlling our interactions, and this includes our cultural, digital interfaces and social contexts. Bazzichelli asks us to stare into the monster’s face – what Bifo sees as a deep emptiness. She pulls out of the slimey depths a glimmer of hope and an advancement for playful and critically aware forms of artistic disruption. It is an academic and cultural hack and reminds me of Donna Haraway’s proposition in the mid 90s for Situated Knowledges. Haraway realised with other collaborators that it was a fantasy to think that the patriarch was going to somehow willingly hand over control and be enlightened to the idea that women scientists should be accepted as equal in history and academia.

“We seek not the knowledges ruled by phallogocentrism (nostalgia for the presence of the one true world) and disembodied vision. We seek those ruled by partial sight and limited voice – not partiality for its own sake but, rather, for the sake of the connections and the unexpected openings situated knowledges make possible. Situated knowledges are about communities, not isolated individuals.” [4] (Haraway 1996)

Her proposition is not suggesting that critical, ethical artists and pranksters give up and put down their tools and become business men and women instead. Using terms such as ‘disrupting business’ is not conforming or giving up the fight. It is a shift in strategy. She has successfully illustrated that there is a continual rise in imaginative experimentation where artistic hacking with the protocols, interfaces, code, data and surveillance is alive and well. It is about infiltration of these ideological defaults and the power systems that rely on them. Resistance is not futile, it is just changing direction from reliance for absolute desire (which lets face it is rarely fullfilled) from momentary tactics and momentary hacks, into informed hacking with socially aware and engaged strategies. She is asking for an intelligent response, a less macho way in dealing with the problem. This means building deeper relations with others through affinities and sharing critical knowledges while disrupting the business of neoliberalism. And most of all, carry on playing…

Featured image: Cardboard Soldier, 2009 exhibition T-Space Gallery Beijing. Joseph DeLappe.

Joseph DeLappe’s art projects have received much interest ranging from the art world, New York Times, Wired magazine, and publications such as Joystick Soldiers The Politics of Play in Military Video Games, the first anthology to examine the reciprocal relationship between militarism and video games. DeLappe is considered a pioneer of online gaming performance art. His art examines the conditions and processes of cultural information to provoke and critique the state of military influences on everyday culture and people’s lives.

DeLappe’s work includes the controversial game based, performance and intervention, Dead in Iraq 2006-2011. This involved him frequently visiting the US Army’s online recruitment game and propaganda tool America’s Army. Using the login name dead-in-iraq, he methodically typed in all of the names of U.S. service personnel killed in Iraq, co-opting the Army’s own technology challenging the official figures as a reminder to its players of the real consequences of war. He also directs the iraqimemorial.org project, an “ongoing web based exhibition and open call for proposed memorials to the many thousand of civilian casualties from the war in Iraq.”

Joseph DeLappe, “dead…whats your point?” dead-in-iraq screenshot 2006-2011.

“The players ask DeLappe to stop what he’s doing, but when he continues they shoot him or simply kick him out of the game. You can see the strong reactions from the other players as a proof that DeLappe’s performance are successful. He succeeds to break the game illusion, in the same way as Brecht “Verfremdungseffekt” breaks the illusion in drama.” [1] (Jansson)

Much of DeLappe’s work is known for challenging his own nation’s involvement with war. However, if we look at The Salt Satyagraha Online: Gandhi’s March to Dandi in Second Life 2008, his work reflects a wider context introducing his concerns on the human condition. Over the course of 26 days, from March 12 – April 6, 2008, using a treadmill customized for cyberspace, DeLappe reenacted Mahatma Gandhi’s famous 1930 Salt March. “The original 240-mile walk was made in protest of the British salt tax; my update of this seminal protest march took place at Eyebeam Art and Technology, NYC and in Second Life, the Internet-based virtual world.” [2]

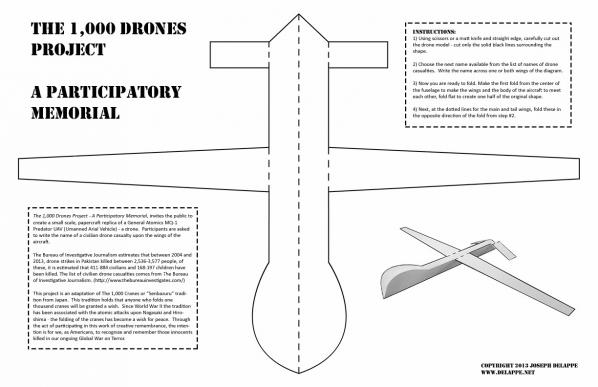

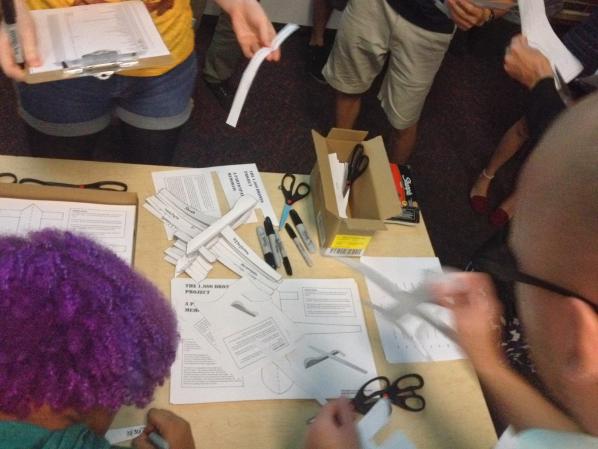

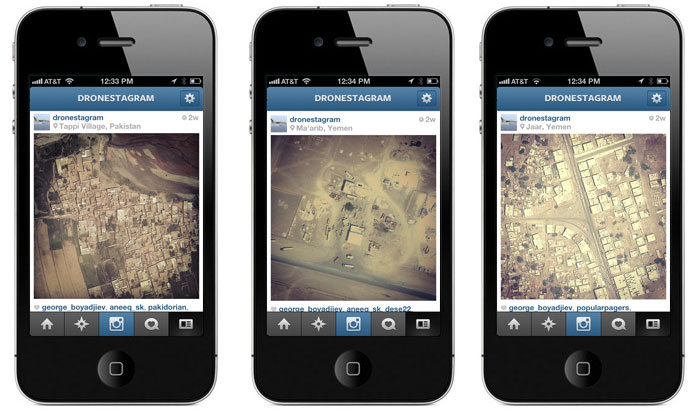

On hearing about DeLappe’s The 1,000 Drones Project – A Participatory Memorial, I was immediately intrigued. I wanted to find out more and discuss his approach as well as how he intends to bring to light the lives lost by these unmanned Arial predators as an art project, and what this would look like.

Marc Garrett: Could you tell us why you felt it was necessary to do this project even though there is already much media attention out there relating to the use of drones in domestic, military and commercial culture?

Joseph DeLappe: There has indeed been much media attention surrounding the use of militarized drones as a part of US foreign policy. Our drone policies have received much attention yet, as with the coverage of civilian casualties from the Iraq war, the actual human costs of our drone strikes remains rather illusive. Through the work I am doing regarding drones that specifically focuses on memorializing civilian deaths I hope to actualize the estimates of civilian deaths and to call into question the moral issues surrounding such remote killings. You might say that drones have struck a nerve with me. There is something different about drones. They seem to perfectly combine aspects of our worst fantasies of digital technologies, interactivity, computer gaming and war. One might consider them a bit of a “gateway” weapon (the drug reference is of course intentional here). I suspect we have indeed opened a Pandora’s box leading to the further utilization of remote and robotized weaponry that will make our current drone usage seem quaint.

The above is “An ongoing series of image interventions downloading images of UAV’s (unmanned arial vehicles) in use by the United States Military, including: General Atomics MQ1-Predator Drone, MQ9 Reaper Drones and Global Hawk Drones from the top results of Google image searches. Each image is slightly adjusted to include the marking “COWARDLY” upon it’s fuselage. The saved images are uploaded to my website with basic titling information “Predator Drone”, “Reaper Drone”, “Global Hawk Drone” – with the intention of having these images begin to appear in searches for information and images on drones occurs online. The works are intended as a subtle intervention into the media stream of US military power.” DeLappe

I am working on several drone projects at the moment, including The “1,000 Drones Project – A Participatory Memorial”, and seek to draw attention to and creatively memorialize those innocents killed by drones. It invites the public to create a small scale, papercraft replica of a General Atomics MQ-1 Predator UAV (Unmanned Arial Vehicle) – a drone. Participants are asked to write the name of a civilian drone casualty upon the wings of the aircraft.

This project is an adaptation of The 1,000 Cranes or “Senbazuru” tradition from Japan. This tradition holds that anyone who folds one thousand cranes will be granted a wish. Since World War II the tradition has been associated with the atomic attacks upon Nagasaki and Hiroshima – the folding of the cranes has become a wish for peace. [3]

MG: You are inviting participants to be a part of the project. In what capacity will they be taking part?

JD: The 1,000 Drones Project has been commissioned by the FSU Art Museum of the exhibition “Making Now – Art in Exchange”. The FSU Department for Art has for the past few months conducted a series of workshop events where the public is invited to make a small, paper drone from a provided template. The form is made directly from MQ1 Predator Drone plans found online. The drone shape is cut out, there are then five dotted lines denoting where to fold the paper – the result is a simple paper facsimile of a drone. Once the drone is created, the participant is invited to write the name of a civilian drone casualty along with their age at the time of death, upon the wings of the drone. The Bureau of Investigative Journalism estimates that between 2004 and 2013, drone strikes in Pakistan killed between 2,536-3,577 people, of these, it is estimated that 411-884 civilians and 168-197 children have been killed. The list of civilian drone casualties comes from The Bureau of Investigative Journalism. We are also using a list of drone casualties from Yemen found here: http://en.alkarama.org/documents/ALK_USA-Yemen_Drones_SRCTwHR_4June2013_Final_EN.pdf

At present we have a total of 464 persons identified as civilian drone casualties from Pakistan and Afghanistan. To complete the 1,000 drones, the remainder will be marked “unknown”.

The paper drones are to be strung together in groups of 18 per string, 55 strands will be hung in the center of the gallery to create an installation that will be triangular in shape. The making of the drones will continue with the opening of the exhibition in February until 1,000 are complete and installed.

MG: What will others learn or gain from this participation?

JD: This is difficult to pin down. My intention is that through the act of making a drone, followed by writing a name or “unknown” upon their creation that individual participants will in some small way actualize the loss of individual lives due to our drone attacks. The intent is to perhaps for some brief moment make real these deaths taking place in our name on the other side of the globe. The actions are decidedly low-tech as well – there is something important in this – the deaths become physical, perhaps drawn from the digital media stream, the digital process of the killings to a direct, physical act of making and remembering. I am very interested as well in the overall effect of the piece – to see 1,000 white paper drones hanging in space as a memorial will likely have a powerful impact. Numbers of civilians killed as reported through our media are all too often numbing and abstract – this piece will hopefully make real this abstract process of digitally remote killings.

MG: What is the lineage of this project?

JD: I’ve been working intensively over the past decade to creatively shed light on civilian and military casualties as a result of our ongoing “war on terror”. This includes “dead-in-iraq”, my intervention as a memorial and protest taking place within the America’s Army computer game and iraqimemorial.org, a crowd sourced project launched in 2007 inviting anyone to post concepts, imagined memorials to the many thousands of civilian casualties from the Iraq conflict.

Looking at DeLappe’s breadth of work informs us how detailed and complicated the subject is, and it equally reminds us how distant we all are from any quality debate about war and drone technology and the impacts these militarised technologies have on citizen’s lives. Thankfully, on the subject of drones the Internet is supplying us with different view points that mainstream news media fails to seriously investigate. Russia Today, reported that classified documents from the CIA could not “confirm the identity of about a quarter of the people killed by drone strikes in Pakistan during a period spanning from 2010 to 2011.” [4]

Kate Rich and Natalie Jeremijenko in 1997 as part of the then, anonymous Bureau of Inverse Technology were pioneers of the first art drone ‘The BIT Plane’. This work was featured in a group show at Furtherfield’s gallery, Movable Borders: Here Come the Drones! in May 2013. [5] In an article in Mute magazine Rich wrote, “The morally disgusting asymmetry of drones relates not only to their deployment by the powerful against the weak, but also to the radical disparity of risk entailed in exposing the defenceless living to pilotless killing machines.” [6] This brings to mind how vulnerable we all are to the whims of the powerful. This feeling of fear will strike at the heart of any humanist not on the ‘right’ side of those wielding such awsome destruction without challenge, until its too late.

DeLappe’s art not only reflects the militaristic world we are living in he is directly engaged with it. His focus on his nation’s obsession with war echoes what James Hillman wrote in A Terrible Love of War, “Hypocrisy in America is not a sin but a necessity and a way of life. It makes possible armories of mass destruction side by side with the proliferation of churches, cults and charities. Hypocrisy holds the nation together so that it can preach, and practice what it does not preach.” [7] (Hillman 2004)

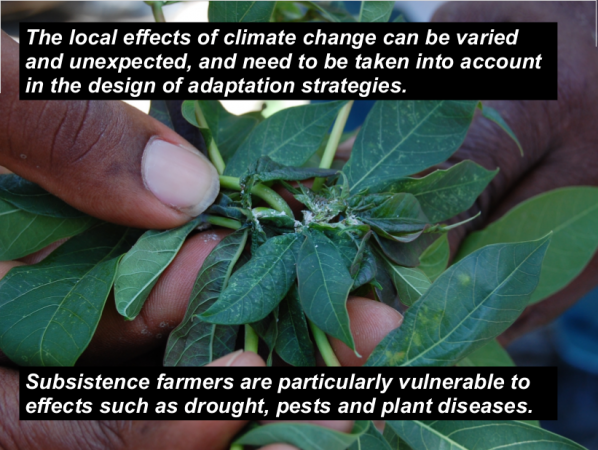

Many contemporary artists are working with and critiquing Bio-Technology, Nano-technology, engineering, issues on Climate Change, border controls, data-mining, surveillance, economic and political fluctuations, and the military. This is in line with the expansion of the networked society. Controversies and battles are taking place in a time of uncertainty, where the very technology and systems that have supported progress, through its worldwide channels of production and prosperity; are now the very same tools threatening the survival of our species, contributing to climate change and the emergence of the economic, global crisis, as well as a threat to our civil liberties. Art and critical thinking examining this complex and strange territory and its impacts on us and the planet are right up there in pushing forward a new kind of radical investigation as an art practice.

Joseph DeLappe’s next exhibition ‘Social Tactics’ will be from January 24 to April 27, 2014 Fresno State Center for Creativity and the Arts, in the US.

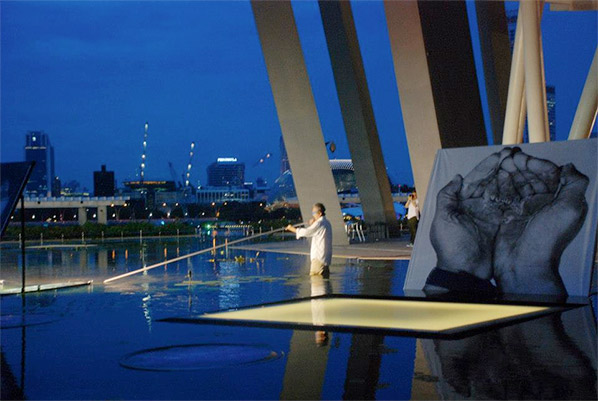

The artist and curator Art Clay was born in New York and lives in Basel. He is a specialist in the performance of self created works with the use of intermedia and has appeared at international festivals, on radio and television television in Europe, Asia and North America. His recent output focuses on large media based performative works and spectacles using mobile phone devices. He has received prizes for performance, theatre, new media art, music composition and curation. As an educator, he has taught media and interactive arts at various art schools and universities in Asia, Europe and North America including the University of the Arts in Zurich. He is the initiator and Artistic Director of the ‘Digital Art Weeks International’ and the Virtuale Switzerland.

Eva Kekou: Could you tell us about your work and what inspires you?

Arthur Clay: The question about inspiration has been posed to me before and most often in the moment when people first see the program that the Digital Art Weeks (DAW) is offering. As an artist I am very much inspired by the every day. I think it is important to be aware of the things around you and by so doing, my artwork seems to have more of a present day dialogue and the events I curate more to do what is actually going on in the society around me. So basically, everything and nothing and all the things in between inspire me. There are no rules, but with a lot of effort to try and come closer to things might be the one I apply the most.

On the one hand, I am a practicing artist and most of this work is concerned with sound. On the other hand, I believe that curation is an art in itself and requires a high level of creativity. It is easier for me to make an artwork in comparison to harmonizing a group of artworks. The two meet in the fact that I grounded the DAW projects in order to provide a platform for my own work and that of others, who think in like minded ways.

EK: You were the curator for the Augmented Reality exhibit “Window Zoos & Views” in collaboration with the participation of the School of Digital Media and Infocomm Techology from Singapore Polytechnic. On the project site, it mentions that the main element of the project was inspired by an image of a car driving down Singapore’s legendary Orchard Road. Could you tell us a bit more about this and the project?

AC: As DAW Director, I am confronted with the same situation each time we bring the festival: Representation and integration. By representation is meant that we have institutions both public and private that act as stakeholders and in turn expect a high level of visibility; talking about integration is much more complex, because there are many levels of integration that must be addressed. First off, the festival structure demands that we integrate local artists into the program along with the international artists participating. Integration of local artists can also mean or entail a high level of knowledge and skill transfer. We do all this during what we like to call the “Exploratory Phase”, which is basically entails dropping the DAW team into a unfamiliar city and making every effort to make it familiar. This includes becoming aware of the general culture the festival will address, how digital that culture is, the art and non art spaces that will become the stage of the festival, and of course trying to find out who is doing what in terms of arts and technology.

To get back to your question about the image of the car driving down the street, the most important element of integration is becoming aware of what is going on in the world of things in which the festival is to be presented. The car we are talking about was a car whose windshield was plastered with cartoon stickers. So, imagine you’re self-sitting at the wheel of that car driving down Singapore’s Orchard Road. It is a really surreal experience; the stickers take on a kind virtual elelment as it floats down Orchard road. The image sparked my imaginations and the AR Parade project was born, which was a very important part of the “Window Zoos and Views” exhibit. Basically, the AR Parade mimicked the effect of the stickers on the car window, but instead of a car windshield, we used an iPhone app to view the images. It was very cool, popular on the street and got a lot of clicks.

EK: There were various artists in the festival showing Augmented Reality art as installations. This included artists such as Tamiko Thiel (DEU), John Cleater (USA), Will Pappenheimer (USA), Lily & Honglei (CHN), Marc Skwarek (USA), Lalie S. Pascual (CHE), John Craig Freeman (USA), and Curious Minds (CHE). It must of have taken a lot of time and energy to organize this, especially the technological aspects of the project. How difficult was it to set all of this up?

AC: In one word: impossible. It is new area of technology, a new approach to curating art, and above all you are dealing with a non-art public – basically anyone who is on the street. That is a big challenge. Add to it the new type of management skills that such an international project work requires and I think you are close to the impossible that I am referring to. For such exhibitions, “Management 2.0” skills are a necessity. The artists, the tech people, and the curators and admins meet and work solely in virtual space. So there are no walls, no tables, and there is no going for coffee together after the meeting. It is a different world from all sides.

Another interesting aspect of this work is that you have to develop a feel for the city and develop a dialogue with it. For the Hong Kong show we did for SIGGRAPH Asia, Monika Rut and I spent about a week working on site, visiting the different areas of the city to check things out and to get a feeling for which works should go where and why. We travel with a lot of special equipment so that we can make tests on site and produce a mock up of the exhibition and test how the experience of viewing the exhibit will be. It is very inspiring but exhausting work and the dialog between Monika and I helped greatly in making all the decisions. Basically, we get to know the cities we are working in quite well and the kick back is, you get to know where the best coffee houses and local restaurants are.