In recent times we have often heard that we’re facing the end of the world as we know it because of factors such as potential nuclear wars, self-sufficient machines, international political crises, and global environmental disaster. However, people in every single age have believed they were heading towards the end of the world. The feeling of being trapped at the end of a road leading nowhere is crucial to understanding why we have needed to apply definitions such as “post-truth” and “alternative facts” to centuries-old rhetorical strategies – creating new terms for the last age of humankind as we know it.

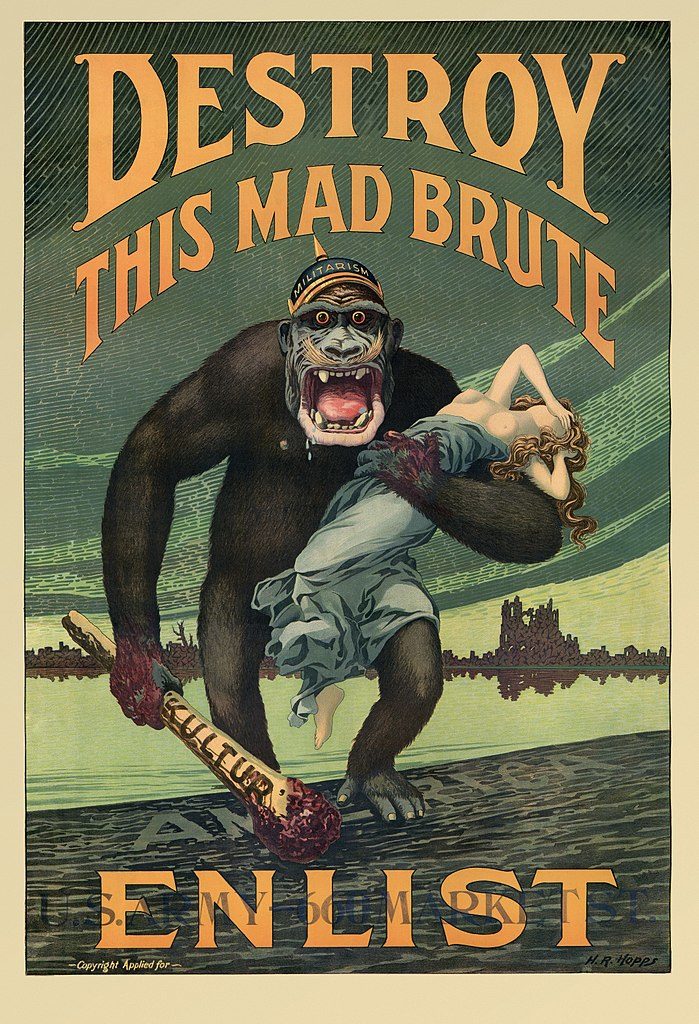

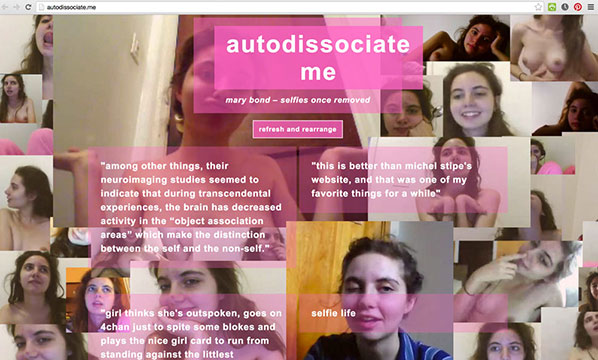

Whilst it may be true that propaganda has been strategically important in shaping opinions since King Darius, the nature of media – from cinematic newsreels created by 1910s national bureaus to today’s social media landscape – plays a crucial role in shaping how strategic messages are created and disseminated. Although we have shifted from the broadcast model of the 20th Century to a mode of prosumption, we are still dealing with the same questions: what effective power does language have? When does a message become propaganda? To what degree can individuals be defined as passive (or active) agents when they share officially approved information? Given these questions, it is no surprise that a number of contemporary artists working with the internet and digital cultures are responding to a perceived crisis of “truthiness” with strategies deriving from the 1910s activity of the Dadaists, a cultural elite who worked in Europe and the U.S. in war times.

Since the 1980s, early artists working with the internet claimed a connection between online art and Dada. It is now important to consider the reasons why, more than two decades later, new generations are still playing in the same field discovered by the Dadaists. The first Dada group was founded in 1915 in Zurich, one of the safest places in Europe, by artists and poets who could afford the journey and the stay. In such a city, anything could be said and written without caring too much about the actual consequences. Broadly speaking, this perceived freedom of expression is analogous to the promises of today’s social media, where everyone purportedly has the same right to share opinions and get involved in discussions as everyone else, without feeling obliged to be politically correct. A sense of detachment is among the features shared by the original Dadaists and contemporary artists with an interest in political questions. Often working in isolated environments, today’s artists use detachment as a strategy by distancing themselves from what’s happening behind the borders and commenting on the daily news, attending to how ‘facts’ have been narrated rather the ‘facts’ themselves.

Another important feature shared both by contemporary artists and the Dadaists is a focus on the ‘flatness’ of communication, which was adopted in strategies of advertising, propaganda and manifesti. This flatness arises since every sentence is an exclamation and the reader’s attention is diverted by unexpected changes and incessant slogans, making the message a discourse without hierarchies. This mechanism makes every part important and urgent, such that, no one part is actually necessary for the economy of the message.

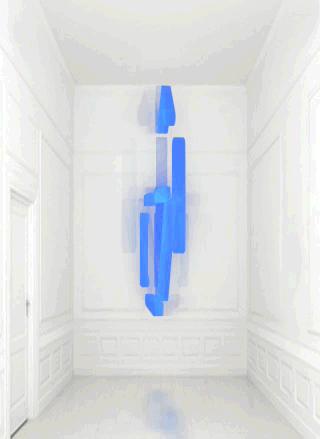

A century ago, a political or artistic group couldn’t be defined as such if it didn’t publish at least a founding manifestoin a newspaper. To write a manifesto meant to impose a vision of the world, to claim the priority of some values in respect to other interpretations. Nowadays people rarely make manifesti, but a spectacular exception is Google’s list of guidelines for Material Design. These aim to spread the word about a “unified system that combines theory, resources, and tools for crafting digital experiences”, a mission recalling those stated by avant-garde and modernist groups to rebuild the world according to a unifying principle embracing all aspects of human beings. Artist Luca Leggero followed the guidelines provided by Google to make #MaterialArt (2017), colourful plastic art sculptures challenging the definitions of artwork and design pieces. Leggero critiques Google’s objective to reconstruct reality under its terms by putting into practice an accelerationist strategy; if everything must become part of the Google-branded world, why not art?

In the 1910s, groups published as many manifesti as possible in order to maintain interest among the public.4 To respond to their dogmatic and flat communication mode, however, Dadaists created countless statements that were not linked with each other whatsoever. For the Zurich group, the goal was to generate noise in the endless stream of commercial and political propaganda; it was a joyful activity that, with its randomness, confirmed the nonsense of all the other official communications. Today, the production of noise, and the disruption of corporate and political communication platforms is the aim of many artists’ practices, but only a few of them are so incisive as Ben Grosser’s. “ScareMail” (2013) is a web browser extension that originated in the midst of the 2013 NSA surveillance scandal. For every new email, it adds an algorithmically generated narrative comprising terms that would likely ring an alarm bell at the NSA.

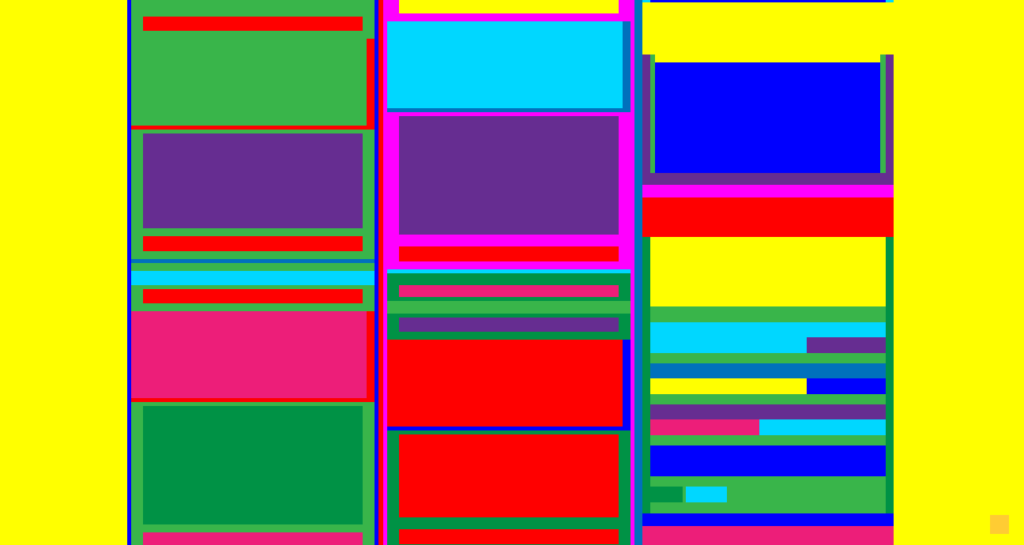

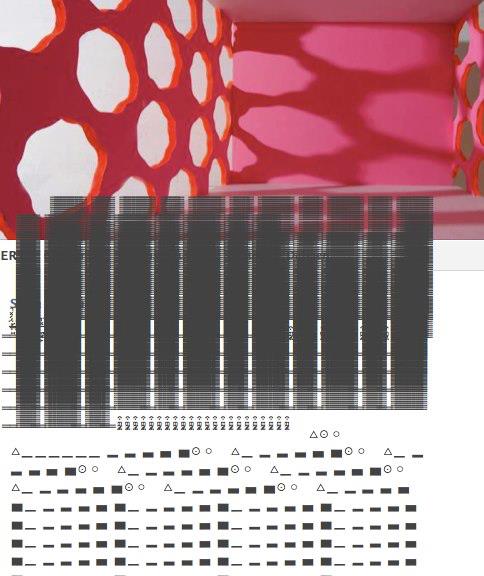

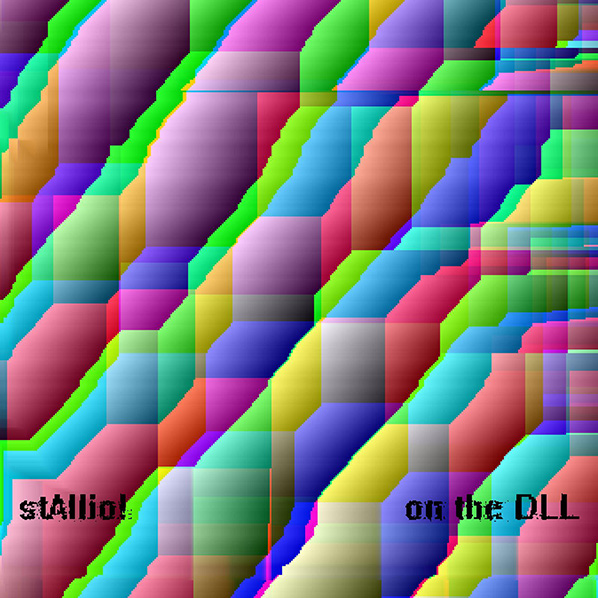

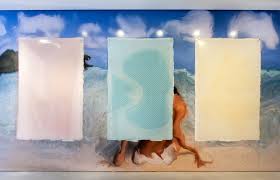

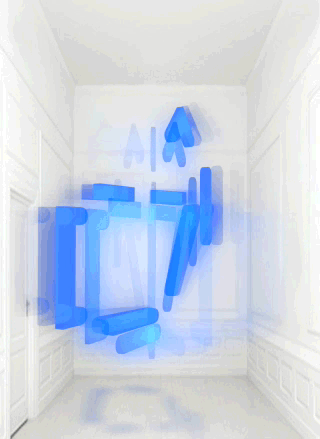

Given the importance of ‘flat’ communicative hierarchies in Dada practice, it’s not surprising how many Dada artists studied the concepts of randomness and entropy as a way of making new realities. There is not just one reality, they seemed to claim, but too many to even imagine; there is not just one imposing point of view, but many – and these may not concur with each other. An exemplary case is a series of collages by Hans Arp arranged according to the Laws of Chance, which didn’t mean they were made without the exercise of any control, but that the artist arranged the pieces automatically, by will. An interest in automatism can be found in many contemporary artists using algorithms as artistic tools, such as Rafaël Rozendaal with Abstract Browsing (2014), a Chrome extension that turns any website into a colourful composition. HTML is a language and as such, it can be read by the browser in many ways, not only the one used by developers and designers. Rozendaal’s work shows the random potential innate in anything, while suggesting there are alternative ways to consume given contents.

“Abstract Browsing” (2014), Rafaël Rozendaal

The production of noise seems to have been the most disruptive response to nationalist propaganda and corporate advertising produced by the original Dada groups. Most of these artists challenged the dogmatic, exclamatory tone used in the official language of war bulletins and newspaper adverts. Taking advantage of this tone and using it in chance-driven messages allowed them to reveal the absurdity of the dogmatic nature of propaganda and advertising.

Many contemporary artists are more or less consciously keeping alive these practices and producing their own kinds of noise in the face of fake news and alternative facts. Nowadays, not only do governments and advertising companies subtly practice dogmatic and exclamatory strategies, but it is even taken for granted they can and indeed do put into practice such disruptive ways to spread messages. When propaganda exploits guerilla strategies, and is generated in the same way art projects disrupt media environments, how should artists respond? This is one of the most challenging issues some artists want to address and the next few years will be a rich (and noisy) testing ground for many of them.

Compiler is an experimental platform organised by curator Alisa Blakeney, artist-curator Tanya Boyarkina, artist Oscar Cass-Darweish and choreographer Eleanor Chownsmith, all currently students of MA Digital Cultures, Goldsmiths. The platform is being built in order to “support collaborative, process-driven projects which connect artists and local communities in networks of knowledge-exchange”.

The organisers of Compiler describe it as a kind of ongoing prototype, a structure constantly negotiating the openness to maintain links to varied practices with the coherence of framing, containing, and describing some of the complicated products of digital-analogue interactions. Their focus is looking at what ‘digital culture’ means and having a productive conversation about it.

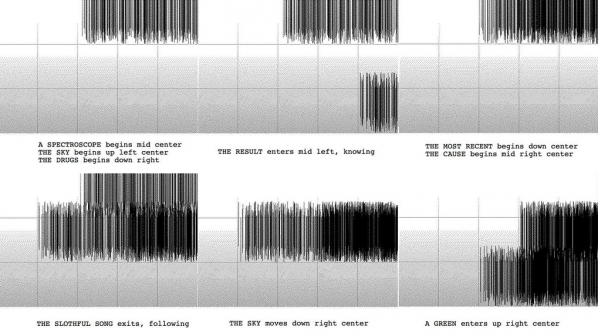

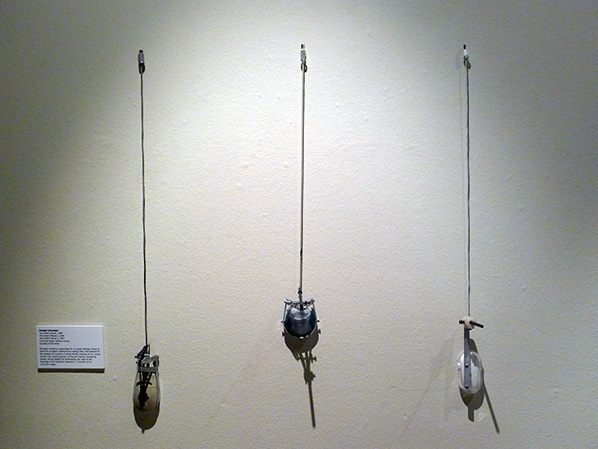

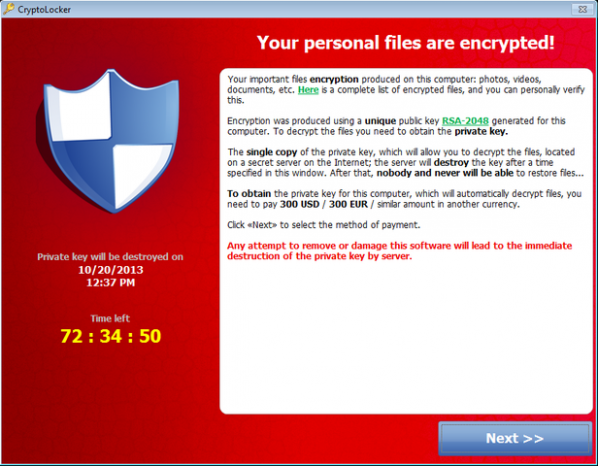

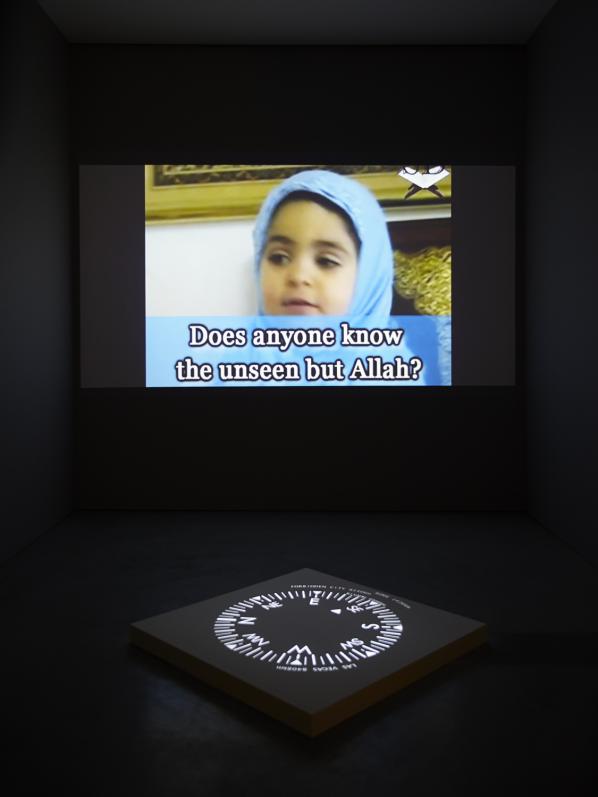

From 6-8 April, the first Compiler, Play Safe took place downstairs at OOTB in New Cross. The exhibition examined practices of surveillance inherent in “states, corporations, technological spaces and the idioms of digital art”. It questioned whether an increasing intensity of surveillance is linked to control, extraction and politics, or can be understood as a pleasurable phenomenon. People were invited to “Dance a website, see through the eyes of a computer, and have our cryptobartender mix you a cocktail to cure your NSA woes”. The work on show, made by students from MA Computational Arts and MA Digital Cultures (both Goldsmiths), included Eleanor Chownsmith’s software and performance which turned website HTML into dance routines, Michela Carmazzi’s photographic project documenting the reactions of Julian Assange and his supporters following the United Nations’ ruling about his case, and Saskia Freeke’s machine which repeatedly and intentionally failed to create a ticker-tape parade using sensors and fans.

An exhibition on the theme of surveillance creates a strange grey area for itself when shown in a building with nine screens of CCTV footage. Oscar Cass-Darweish’s project made a fairly direct link to the CCTV cameras which emphasised this greyness. The project produced a rendering of the exhibition space by using a function usually found in motion detection processes. This function calculates the difference in pixel colour values between frames at a set interval and averages them, creating a visual output of how machines calculate difference over time.

Another work which made links with the room upstairs was Fabio Natali’s Cryptobar, where following an interview with the ‘bartender’ about your data privacy needs you were recommended a cocktail of data-encryption software. Upstairs you could buy, and drink, a cocktail with the same name (the Cryptobar was part of the V&A Friday Late on Pocket Privacy on 28 April).

So far, Compiler has made a variety of spaces for conversation about digital culture through both its artworks and its organisation. Each artwork has a different ‘footprint’ of interactions, linking websites to rooms, success to failure, data privacy to financial transaction via consultation, and making interesting connections between CCTV and code, dance notation and HTML, activism and commerce.

An interesting way to read the Compiler platform is as a series of combinations of human-readable codes and machine-readable codes. The platform ‘compiles’ a different combination each time, and each time the output is different. Through this, the interaction of analogue and digital processes is demystified and muddled, in a distinct way. The platform is in its early days, but it seems likely that new connections and new grey areas will appear over the next few months, as Compiler has its second exhibition (again at OOTB) in May, takes part in the CCS conference at Goldsmiths in June and heads in other directions thereafter.

The exhibition offered plenty to play with, while posing complicated problems in relation to openness and experimentation. When I spoke to Eleanor, Tanya and Alisa about Compiler and its aim to engage local communities in networks of knowledge-exchange , we talked about how it’s an impossible and strange aspiration to have a ‘neutral’ venue. While a cocktail can be delicious and engaging, it’s also expensive. While a cafe is, arguably, a less exclusive space than a gallery, OOTB itself is a cafe which targets a specific audience. Drink prices, decor and a host of other factors mean OOTB, like all spaces, is politicised in a particular way. Their venue choices so far will influence, in subtle and overt ways, their future attempts to engage diverse local communities. The organisers of Compiler acknowledge this; their response is that rather than trying to make an artificial neutrality they are keen to move as the platform develops to new spaces and new and different contexts.

A change of context, message, communication style is not easy; nor does it fit with to an easily recognisable politics or aesthetics. Moving into and out of contexts is something to be done carefully and thoughtfully. It seems to me that the Compiler team will have their work cut out, but if they can direct that work in such a way that the platform is able to communicate in multiple ways at once, ‘networks of knowledge-exchange’ could develop between, and in response to, the markers set by the organisers. The question is, how will they develop?

Choose Your Muse is a new series of interviews where Marc Garrett asks emerging and established artists, curators, techies, hacktivists, activists and theorists; practising across the fields of art, technology and social change, how and what has inspired them, personally, artistically and culturally.

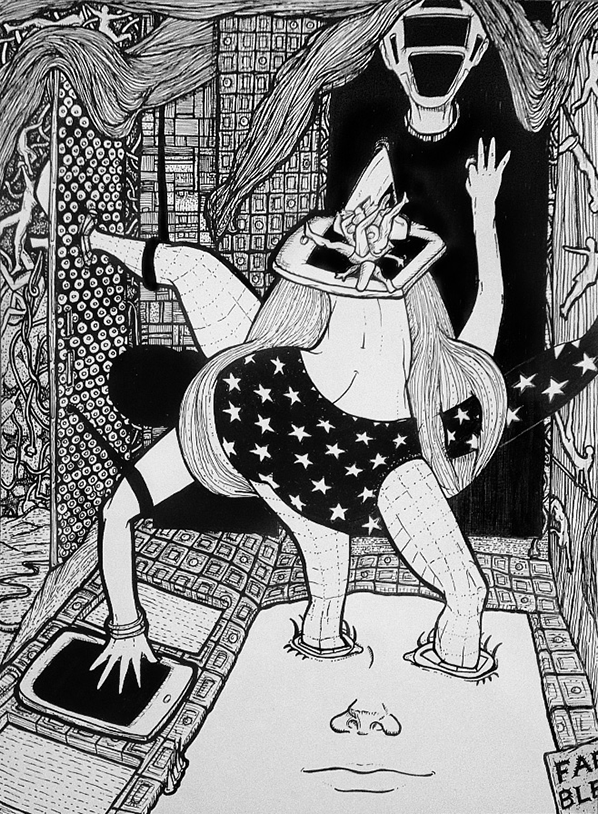

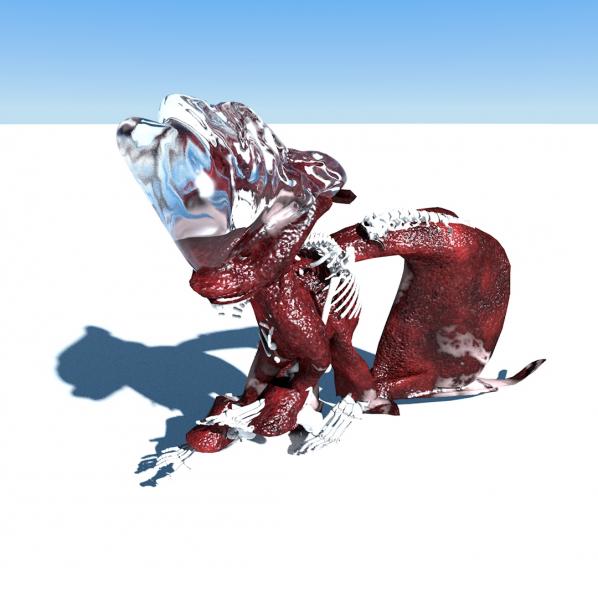

Gannis is informed by art history, technology, theory, cinema, video games, and speculative fiction, expressing her ideas through many mediums, including digital painting, animation, 3D printing, drawing, video projection, interactive installation, performance, and net art. However, Gannis’s core fascinations, with the nature(s) and politics of identity, were established during her childhood in North Carolina. She draws inspiration from her Appalachian grandparents singing dark mountain ballads about human frailty, her future-minded father working in computing, and a politicized Southern Belle of a mother wearing elaborate costumes, performing her prismatic female identity.

“I am fascinated by contemporary modes of digital communication, the power (and sometimes the perversity) of popular iconography, and the situation of identity in the blurring contexts of technological virtuality and biological reality. Humor and absurdity are important elements in building my nonlinear narratives, and layers upon layers of history are embedded in even my most future focused works.” Gannis.

We begin…1. Could you tell us who has inspired you the most in your work and why?

The complete list of people who have inspired me is inordinately long. I’m sharing with you here clusters of some of the “most most” inspiring.

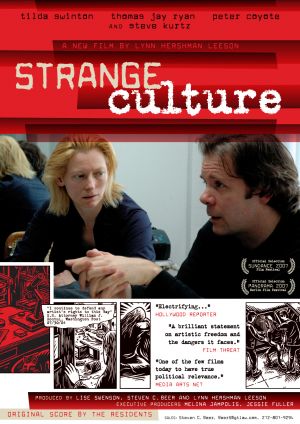

Lynn Hershman Leeson, Maya Deren, Lady Ada Lovelace, Mary Wollstencraft – I saw Lynn Hershman Leeson’s Conceiving Ada in the late 90s. It was my first introduction to her work, and

I have been blown away by her prescience ever since. Deren, Lovelace, and Wollstencraft, like Leeson, have all been groundbreaking in their creative, scientific and intellectual contributions to humankind.

Yael Kanarek, Marge Piercy, Octavia Butler, Sadie Plant, Jonathan Lethem, Harry Crews and Flannery O’Connor – Artist Yael Kanarek’s “World of Awe” was one of the first net art pieces, through its poetry and world building, to inspire me to transition from painting into a new media arts practice. Piercy and Butler are two favorite authors, and they have both written novels where women travel into the past and to the future to reconcile their identities, to come to terms with their present selves — themes that constantly recur throughout my work. Plant opened up broad vistas to me as a woman and feminist working with technology, and the melange of genres Lethem mashes up in his fictional works: sci fi, noir, autobiography, and fantasy, appeals to my own hybrid sensibilities. Crews and O’Connor testify to the absurdity of the human condition, and being a native of the “American South,” their gothic sensibilities resonate with me deeply.

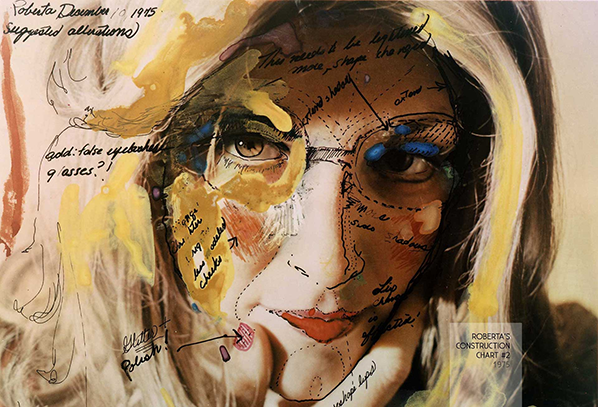

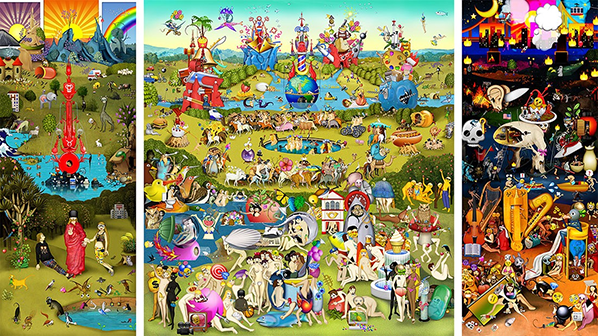

Philip Guston, Suzanne Valadon, Artemisia Gentileschi, Louise Bourgeois, Hieronymus Bosch and Giotto di Bondone – I studied painting at a school where Guston had taught (many years before I arrived there), and coincidentally we share the same birthday. I have always felt a very strong connection to his work, particularly to his late work, where he resisted the art establishment and made pictures that he felt truly represented his time. Valadon, an autodidact, likewise bucked the conventions of 19th century “lady painting” focusing on the female nude throughout her oeuvre. Gentilsechi in the 17th Century established herself as an artist who painted historical and mythological paintings, rendering women with more agency and strength than her male contemporaries. Bourgeois’s work, the rawness of her drawings particularly, were quite significant to me as a young artist. Twice I got to attend her Sunday Salons in New York, sharing my work with her. She was a tough critic by the way. Bosch and Giotto have long been favorites, the enigmatic quality of Bosch’s vision, and the amalgam of Medieval and Renaissance perspectives colliding in Giotto’s paintings.

Charlie White, Laurie Simmons, Gregory Crewdson, Renee Cox & Cindy Sherman – I think of these photographers as important conceptual forerunners of a Post-Photography movement that seems to be reaching its apogee now. They were each essential to me as I searched for a new aesthetic language, after throwing away my oil paints and canvases.

And today there are so many younger artists who I have deep respect for, Gretta Louw, Angela Washko, RAFiA Santana, Jeremy Bailey, Lorna Mills, Andrea Crespo, Clement Valla, Faith Holland, Jacolby Satterwhite, Morehshin Allahyari and Alfredo Salazar-Caro (to name only a few). They all have significant presences online, and I encourage readers to “google them” for glimpses into the contemporary visions that are shaping and predicting our future.”

2. How have they influenced your own practice and could you share with us some examples?

In my teens and 20s I copied much of the work of my sheroes and heroes. There is little I can share with you of that work now, as I’d copy then delete back then. To be more accurate, since it was physical work, I’d copy and destroy. I destroyed more work than I saved until I found a way to absorb and remix through the filter of my own identity.

Today I identify as a visual storyteller who cuts and pastes from the threads of googleable art history, speculative fiction and networked communication in efforts to aggregate some kind of meaningful narrative. Appropriation feels like an authentic artistic response to mediated culture, registering at a different conceptual frequency than simple mimicry. I mean making a painting like Giotto or Bosch doesn’t make sense in the 21st century, well, unless you “emojify” it (wink). Here is one recent work where my quotation is obvious, “The Garden of Emoji Delights.” In the other works below, a collection of influences are embedded, but perhaps less perceptible on first glance.

3. How is your work different from your influences and what are the reasons for this?

It is essential that my work be different semiotically from the historical influences I mentioned above, if I am to actually understand the nature and power of their work — how each of them were incredibly perceptive and responsive to “their time.” They produced authentic images or texts (or code) that were assembled from aspects of their cultural milieu. Their expressions were comprehensible to their contemporaries, even if at times only a few of their peers engaged. Communication is key to every human enterprise. Nonetheless the infinite (and often futureminded) perspectives of these historical figures still reverberate in our contemporary collective consciousness and influence us to “perceive differently” in our own time.

To be different from influences who are of my own time also involves comprehending why they have an impact on me. They avoid any kind of creative and intellectual status quo. Being unique seems improbable in the internet age, but there are still innumerable ways that we can creatively parse our relationships to the past, present and future, both in concert and contrast to one another.

4. Is there something you’d like to change in the art world, or in fields of art, technology and social change; if so, what would it be?

There are many art worlds. In the more mainstream, celebrity-dominated, auctioneer enabled art world, whose market I rarely follow, but when I do, I find it to be bloated by One Percenters consumed by commodities trading, I would advocate for, if I had the power to do so, more economic temperance, less aura fetishization, and yeah, VR headsets that provide clothes for hackneyed metaphors.

It’s demoralizing that I cannot foresee, at least in the short term, a world without radical income inequality. Our world continues to be populated by a majority of “have nots” who are dominated by a tiny dominion of “haves.” It seems in every financial, social, educational, and entertainment sector, including the visual arts, capital obstructs as much as it supports creativity. Still I believe that the “other art worlds” can and will affect, actually currently are affecting change (incremental as it may seem), through social advocacy programs that embrace and foster diversity; through economic and technological models that celebrity the ubiquity instead of the scarcity of contemporary digital art; through independent artists who define their success in terms of cultural, instead of, or in addition to market value.

Positive changes are happening. Compare our cultural landscape to even two decades ago, and we see a much more diverse population represented in the arts. A new generation of artists and technologists are hopeful about their capacity to shape a better future, while being mindful of what’s a stake if they do not.

That said, and to finally answer your question directly, I’d like to see a change — a major turn in the tides of fascism, racism, xenophobia, and misogyny that are flooding countries around the world — so that the various art worlds, the ones that frustrate me, and the ones that inspire me, can survive.

5. Describe a real-life situation that inspired you and then describe a current idea or art work that has inspired you?

Sitting with and drawing digital portraits of my 99 year old Grandma Pansy Mae in January of 2015 inspired me to begin “The Selfie Drawings” project. Being in the presence of someone who has witnessed so much radical social and cultural change, over the course of almost a century, motivated me to interpret, and then stage a series of reinterpretations of myself/selves, within the context of a post-digital age. Pansy Mae was a woman born before women had the right to vote in the United States, a woman with only an 8th grade education who raised my mother, and myself to never let our gender or our class (personally) deter us from pursuing our ambitions. Grandma is now 101 years old, and I wished her Happy Birthday in binary code this past December 31st.

“Nasty Woman” is a current meme that has really struck a chord with me. I have worn a “Nasty Woman” necklace everyday, since November 7th, (the day I picked it up from the studio of artist Yael Kanarek). Embracing the nomenclature that was meant to denigrate a woman has instead empowered and galvanized a collective of women as they face, and resist, the alarming possibilities of increased subjugation under Trump’s leadership.

I recently participated in the NASTY WOMEN exhibition in New York city, (which raised over $42,000 for Planned Parenthood), because I am such a woman, a nasty woman, a bitch, a Jezebel — a complex and empathetic human being who believes change and equality can only occur when we speak up, when we eschew “politeness” in the face of serious threats to our autonomy and personhood.

6. What’s the best piece of advice you can give to anyone thinking of starting up in the fields of art, technology and social change?

I’ve got a few bits of advice. First, as an artist, work; as a technologist, feel; and as an advocate for social change, empathize. Then toss up your FEW cards (feel, empathize and work) and apply them to other aspects of your life as well.

Secondly I suggest losing, if you possess, the sense of what you think you’re entitled to because you are more special and deserving than others. This doesn’t mean you deny the gifts you possess. Nor does it mean you eschew your ambitions or balk at your successes. Brand yourself, or your cause, by all means, if that informs your practice or generates support for your work. But the “I’m a genius, so I have the right to be licentious, egotistical and completely selfserving at the sacrifice of others” trope may (temporarily) get a man into the White House, but generally is tiresome, if not loathsome, to progressive art professionals.

7. Finally, could you recommend any reading materials or exhibitions past or present that you think would be great for the readers to view, and if so why?

What I’ve been reading lately: Object Oriented Feminism edited by Katherine Behar; Artemisia Gentileschi, The Language of Painting by Jesse Locker; Lynn Hershman Leeson Civic Radar edited by Peter Weibel; Hope in the Dark | Untold Histories, Wild Possibilities by Rebecca Solnit; The Year of the Flood by Margaret Atwood

I recommend these books as a resistance to sophomoric twitter threads usurping all of your attention.

Pipilloti Rist : Pixel Forest New Museum, http://www.newmuseum.org/exhibitions/view/pipilotti-rist-pixel-fores

It is okay for art to wash over you, so that you can revel, even relax, in its beauty…for a while.

____________________________________________________________________

Monster of the Machine : Laboral

curated by Marc Garrett http://www.laboralcentrodearte.org/en/exposiciones/monsters-of-the-machine

A timely and provocative exhibition (thrilled to have work included).

__________________________________________________________________

Dreamlands: Immersive Cinema and Art 1905-2016

http://whitney.org/Exhibitions/Dreamlands

A landmark show for moving image works!

__________________________________________________________________

Women’s March On Washington (Saturday, January 21st!) https://www.womensmarch.com/

…or one of the other 386 protests taking place on the same day around the world!

https://www.womensmarch.com/sisters

#notmypresident

Choose Your Muse Interview: Jeremy Bailey | By Marc Garrett – 26/06/2015

http://furtherfield.org/features/interviews/choose-your-muse-interview-jeremy-bailey

Choose Your Muse Interview: Annie Abrahams | By Marc Garrett – 10/09/2015

http://www.furtherfield.org/features/interviews/choose-your-muse-interview-annie-abrahams

Choose Your Muse Interview: Lynn Hershman Leeson | By Marc Garrett – 13/07/2015

http://www.furtherfield.org/features/interviews/choose-your-muse-interview-lynn-hershman-leeson

Choose Your Muse Interview: Stanza | By Marc Garrett – 03/11/2015

http://www.furtherfield.org/features/interviews/choose-your-muse-interview-stanza

Choose Your Muse Interview: Igor Štromajer | By Marc Garrett – 09/06/2015 http://www.furtherfield.org/features/interviews/choose-your-muse-interview-igor-%C5%A1tromajer

Choose Your Muse Interview: Mike Stubbs, Director of Fact in Liverpool, UK | By Marc Garrett – 20/05/2015

http://www.furtherfield.org/features/interviews/choose-your-muse-interview-mike-stubbs-director-fact

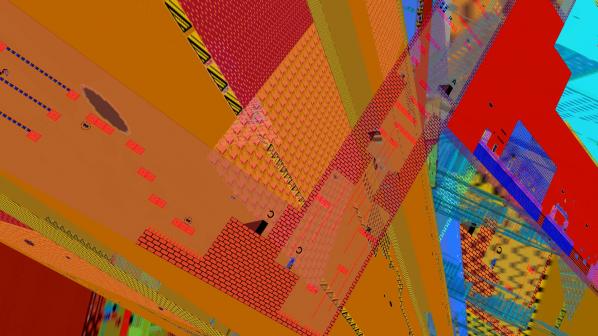

In many of the projects by French Vancouver-based artist Nicolas Sassoon, space and how we perceive it are two of the most inquired questions; it could seem casual that he mostly makes GIFs, but looking at his works you’ll realise the necessity of reflecting on environments, both artificial and spontaneous, using such a specific format. His works ask the viewer to not stop just at the first impressions; sure, most of his GIFs are astounding in terms of animation, use of colours and shapes, but all this technical skill is employed for inquiring our position within environments – not just laptop monitors, but real, concrete buildings and dreamy contexts as well. This is just one of the many introductory points from which we can start talking about INDEX, his latest work which has been featured on the homepage of Rhizome in the first weeks of October and that can be viewed here, on his website.

FL: One of the first things that struck me about this project is the relation between hypnagogic dimensions and the technical features of GIF format. The never ending loop of events and the way in which you can change your perception of the same object are important aspects of both; I wonder what you do think about this, especially from your point of view as an artist.

NS: INDEX is representing a project space/music venue in Vancouver BC where I co-organized electronic music events in 2015. It is depicted in the process of being setup for an event titled Rain Dance which happened in August 2015. When I started working on INDEX I was curious about the process of rendering a detailed scene from memory. I had many memories of the venue during the installation phase, a few days before the event. I began to render these memories and details from the installation period within what I could remember of the overall architecture. In that regard, INDEX is an effort to recollect and fixate details about this particular space at this specific time. Some parts of the work are relatively accurate while some other parts are imaginary. The hypnagogic and effervescent visual aspect of the work is informed by this process. It’s also informed by the nature of the events that took place at this venue.

FL: Speaking of memory, what could be a connection between it and GIFs in your own opinion? What are the technical features of this format that could it make appropriate as mean to show memories? Since you mostly worked with GIFs for many years, I wonder if you started to experience events and places as objects suitable to be translated into this format.

NS: The most tangible connection I can think of between GIFs and memory has to do with the history of the web since GIF is an image format that has survived throughout the evolution of the Internet; it is an ancient species that has survived numerous cataclysms. In my work, the connection between GIFs and memory comes from a desire to reconnect with specific moments and places, to create a form of record of these memories. The representation of these memories is an opportunity to formulate mental images of architectures, landscapes and other elements into visual forms that are minimal, incomplete, and encoded. I also enjoy using the GIF format as a very subjective archive; for example, in opposition to the objectivity of 3D scans from historical artefacts. INDEX contains some historical and factual data but it’s also completely skewed by my own perspective.

FL: This is an interesting reflection; I like the concept of the GIF format behaving as a selfish gene, in terms of adaptability throughout many different contexts and times. In your own opinion, what is the reason behind the fact it has so much importance in the last 20 years (and counting)? I can’t help but think about the relation between the ways we use to connect to the internet (ie the devices we use, the span of time we stay connected, the reasons we’re connected, etc.) and the faster and faster speed of our internet connections. What do you think?

NS: The continuous presence of GIFs online has to do with the format being perfectly adapted to web environments and its relentless user applications. If you look at early HTML pages, GIFs were always a highlight; they allowed users to add dynamic elements throughout their content. Inserting animations in the middle of text, images or diagrams was a novelty. GIFs embodied that novelty; they were a simple and accessible display of something “multi-media” so they became instantly thought after, heavily used, and stored into databases. GIFs are still pervasive today in forums as image profiles or as punctuation in comments; DUMP.FM personified that within the net-art community, but if you look at any forum or social medias platform it’s still present. From a technical standpoint, the GIF format is attractive because it works like simplified video editing; you set up an image sequence, decide on the speed, and loop it forever. Aside from the APNG format – which never really took off – no other image format offers these capabilities. It covers fundamentals, from traditional animation (frame by frame) but also offers flexibility in terms of input since you can make GIFs from literally anything. The looping function has infinite fields of applications and is impactful visually, which is perfect for the attention seeking nature of Internet space.

FL: Yes, GIFs have been very important in the first years of the Web especially because they bring depth to Web environments; the fact that artists like you are bringing this format from the usual contexts (ie laptops’ monitors, smartphones’ screens, etc) to physical spaces totally makes sense to me. In both cases, we’re talking about fixed environments where the never ending GIF’s movement affects their perception. What do you think? What does it change when you work on a project that will be on display on a Web site and another one which will be hosted on the facade of a building? I’m especially thinking in terms of spaces and perception of shapes and colours…

NS: It has been a challenging process to exhibit screen-based works into physical space, mainly because screen space and physical space are so different in terms of experience. Looking at something on a laptop screen feels intimate, but watching the same thing in a gallery or museum is more of a social experience determined by the immediate architecture. I think a lot in terms of experience in my work and I’ve come to adapt this thought process for installations. I determine the scale of my installations based on the architecture in context. I work primarily with projections whose shapes and sizes references windows, doorways, or other architectural features appearing in the space. These referential elements articulate my work in space like an environment adjusted to the architecture; an added layer which plays with the configuration of the space. I often see my installations as projected sets, or giant digital props injecting imaginary scenarios within architecture. It feels like a natural extension of what I’m trying to do with screen-based works, but it also really engages with the architecture in context.

L: Speaking of the importance of GIFs in our daily online routines, I wonder if and how the so-called GIF art has been influential in respect to the broader use of this format by general public; I’m especially thinking to Simple Net Art Diagram (1997) by MTAA, to the way it used the features of this format to add a little magic to what would look like as a diagram – in other terms, do you think the irony, the cleverness and the experimental approach of the first artists working with GIFs have been understood and implemented by non-experts?

NS: I find early GIFs made by artists as influential as the GIFs made by early web designers, scientists, and other random users involved with the format. GIFs are created from pretty much anything and there has been an infinity of cross-overs in terms of influences. So many users have gone beyond the typical level of involvement with this image format, it would be presumptuous to give credit only to the artists. Still it’s amazing to see the format being acknowledged in the recent historical work on Internet Art, and I’m hoping to see many GIFs in the new Rhizome’s NET ART ANTHOLOGY! I also believe the history of GIF is a history of the vernacular which would deserve its own separate study.

FL: When you see the work, you can’t help but think of ’80s computers; in other terms, the black background and the blinking white dots and lines suggest this association. Can I ask you why you did choose this specific aesthetic?

NS: One of my interests for this type of early computer imaging has to do with the formal and optical properties of these graphics; the way they behave on screens and how they produce kinetic experiences. This is visible in works like PATTERNS where I focus on abstracted animations. Working with these out-dated graphics feels similar to working with an engraving technique or a type of craft that belongs to a certain time period. Some crafts and imaging techniques tend to be associated with specific eras. In the case of early computer graphics, their era is the end of the 20th century which I feel strongly connected to. I also look at these graphics for what they generate in terms of aesthetic experience. They are the primary visual language of the display technology we use today, and they’ve generated many revolutions in the way we perceive contemporary images.

FL: You just highlighted one important aspect of your works as whole; This makes your projects, on one hand, to look modernist as they explore how minimum information can create a kinetic effect, rooted in the belief that objects can be reduced to quantifiable patterns and shapes; and on the other, they are nostalgic, reminding us of the times when when creating digital pictures was not so dissimilar from artisanship. What do you think? Am I wrong?

NS: I’ve always been attracted to the idea of developing a craft or skill as far as possible. My focus on early computer graphics was a conscious choice in that sense. It came quite late in my practice when I felt the need to make art for my own sake, without professional incentives. My generation grew up with the first home computers and there is often a generational shift of perception when it comes to early computer graphics. For me, this aesthetic is linked to childhood, fantasy, entertainment, while for other generations it doesn’t have the same emotional input. But no matter the generation, this aesthetic has a definite “time-stamp” and most audiences will associate this aesthetic with that “time-stamp”. The early stages of my practice were very focused on how to appropriate this aesthetic, to turn it into my own visual vocabulary and to articulate it with elements inside and outside of this specific “time-stamp”. I feel many affinities to painting because of this relationship I have with the visual components of my work.

FL: Speaking of painting, the other day I was reading The Social History of Art (1951) by Arnold Hauser and one text passage struck me in relation to INDEX. “[Mannerism] allows spatial values, different standards, different possibilities of movements to predominate in the different sections of the picture. […] The final effect is of real figures moving in an unreal, arbitrarily constructed space, the combination of real details in an imaginary framework, the free manipulation of the spatial coefficients purely according to the purpose of the moment. The nearest analogy to this world of mingled reality is dream.” Now, I’m not suggesting the idea that your project is mannerist, but I can see some shared features; the way you constructed the space makes me feel a set of arbitrary rules working underneath the blinking white lights, the objects you depicted are somehow real but fixed in a non-realistic dimension. What’s your opinion?

NS: When I began this project, I wanted to develop a new direction that I approached with previous works like STUDIO VISIT. I wanted to portray a real space and make it exist within a different dimension. I was picturing an animated relic, completely isolated and playing itself indefinitely. I focused on my memories of the space and on the reasons that led me to render it. Index was a project space which felt important in the cultural landscape of Vancouver, it also had its own personality. I knew the venue would eventually disappear and be forgotten for the most part. I wanted the work to become an expressive record of this, charged with energy and subjectivity. There is also a form of nostalgia expressed in the visual language I use, and I wanted to articulate this sentiment with the work. This is what led most of my formal decisions. I worked with mental images of the space seen through a lens revealing the energy of each object, and how these objects were infused with the activity of the space. For instance, some parts of the floor were made of these very small sections of hardwood flooring, and it was an area where people used to dance. This translated into a very dynamic area in the work, like a multitude of small conveyor belts imbricated into one another.

FL: It seems to me you used isometric projection to depict the objects, a technique employed mostly in technical and engineering drawings; in fact, the scenes look real but not physically reachable, as if they exist on their own – in other terms, they look eternal, recalling the still life paintings by Italian painter Giorgio Morandi. In his case, unlabelled bottles and unrecognisable objects make the scenes unhistorical and closed in themselves; I think it’s interesting the fact you both employed similar devices to depict still life objects – although it’s clear there are many important differences between your works. What do you think?

NS: I’ve always been interested in using screen-based graphics to express the materiality of physical objects or imaginary structures. This is very apparent in early works like FREE CUTS. These works were created as sketches for sculptures, but in the end, they embodied the sculptures on screen. Like paintings, digital images exist on their own plane, and they can develop their own materiality. In my work, this materiality often manifests as a tension between the flatness of the screen and the sculptural properties of the graphics. Sometimes the work feels like it resides in its own plane of existence, like an object stuck between two worlds. This image of something stuck between two worlds is dear to me because it feels so relevant to my experiences on screens. Things can appear so tangible and so distant at the same time, so desirable yet completely unattainable. With isometric perspective, I find a lot of interesting ideas in ancient Japanese works. Isometric perspective is nothing new but it seems to hold a stronger imprint from engineering drawings and video games than from these much earlier art forms. In the case of INDEX, works like The Tale of Genji – a scroll depicting Japanese interiors from the 12th century – were very inspirational. The scroll depicts social scenes with a good level of detail, and it gives the feeling of overlooking the architecture. The vision is fragmented like in INDEX, and you have to unroll – or scroll – to see the rest of the space. These old works feel very contemporary, probably because isometric perspective has been so used in computer graphics.

Featured Image: Obscurity (2016), Paolo Cirio

Obscurity, the latest project of Paolo Cirio, targets american mugshot websites. Mugshots are one of the utmost paradigms of the inexorable logic of today’s online economy and its controversial ethics; they collect and expose photos of people who have been arrested in the U.S., irrespective of the type of offence, and they profit by placing reputation management ads or by charging a removal fee. The owners of these websites are often anonymous or based offshore. As part of his project, Cirio cloned some the most known mugshots, scrambled the data profiles of the listed individuals and obfuscated their identities. In addition, he programmed the algorithm so that it boosts the ranking of the cloned websites in order to interfere with the activity of the original ones and to therefore sabotage their function. Mugshots can have a decisive role in someone’s life, reinforcing a new form of social stigmatisation defined by search engines results. When visiting the mugshot duplicates, users are invited to decide whether the listed profiles should be kept or removed. Obscurity brings to the foreground critical and complicated issues around today’s privacy and transparency, discussing the current legislative system in the U.S. in comparison to Europe and other parts of the world.

I talked with Paolo Cirio about the challenges and difficulties behind his -once again- daring act and artistic work.

DD: Mugshot websites are based on the exploitation of the anxiety and fear of people who have been arrested in the U.S. It addresses a new form of monetisation that takes reputation management to its extreme. Could you tell us how ‘big’ is the issue of mugshots in the U.S. and what made you develop a project about it?

PC: There are probably over 50 million mugshots on the Internet, and perhaps more, considering that every year in the U.S., city and county jails admit between 11 and 13 million people, an average that has been steadily increasing in the last twenty years. I personally met people that had their mugshots published on those websites and had to pay a removal fee. I would say that this is a very common issue for non-white and low-income Americans, who are the majority, although they’re often neglected by public attention.

I was surprised that this issue was being ignored and not addressed seriously. I couldn’t find any privacy organization in the U.S. focusing on this issue or making a major case for the Right to Be Forgotten in the U.S.

In particular, the several contradictions and complexities of the situation offered me an exciting subject to intervening practically and conceptually. It was the saddest and most delicate material I had ever worked with. However, it was important to address how the flow of information today can impact lives so directly and how art can do something with that. In most of my artworks, I highlight our information society’s legal, economic, and social implications. These fields are all tightly interconnected in this work: the economic value of sensitive information with the personal interest and the legal system with the public democratic interest. I would say that this work is about society as a whole.

DD: At the heart of your project lies an obfuscation algorithm. Obfuscation is a strategy against datafication which has been very much discussed in the last few years. How is it used as part of your project, and why?

PC: The obfuscation of information became quite a sophisticated operation in this work. The huge dataset I assembled with such delicate material could not be wasted or mishandled. That’s why I decided to apply different layers of obfuscation to protect the privacy of the individuals and, at the same time, keep the data accurate.

The algorithm shuffles first and last names and mugshots based on common gender, race, age, and location, making their obfuscated identities similar to the original ones. Meanwhile, for the profile of the person arrested, all the data concerning the arrest is maintained accurately. The individual records provide the social context of the arrest for public scrutiny without exposing the individual. For instance, you can still count how many people of colour have been arrested in a specific county, but it would be hard to identify individuals.

I believe there is a need to learn how to handle sensitive information very carefully, case by case, and to deal with complexity to provide simplicity and not make it more overwhelming. The notion of privacy and transparency can’t be polarized between fears and utopias of big data.

In past years, I’ve been working on several projects concerning the circulation, appropriation and exposure of sensitive information over the Internet. In particular, I made artwork by recontextualizing photos of individuals on Facebook, Twitter, Google Street View, and other online platforms. These provocative works were meant as a warning regarding social media companies’ privacy policies and the danger of losing control over one’s pictures posted online. However, I never let search engines index this personal information or expose their names in all cases.

I believe in a need for an ecology of information. I see information as water; it should be safe, accessible, and clear for everyone’s sake. Any form of pollution could damage an entire ecosystem. Therefore, for me, obfuscating a particular flow of information is more of a technique to clean a toxic spill into a reserve of data that can be essential for a democratic society. Like when it allows public scrutiny over law enforcement agencies. Imagine some operations trying to obfuscate open data or inject fake stories into WikiLeaks. Wouldn’t it be as shameful an act as polluting spring water? In the future, it’ll be even more important to fight to keep the oceans of data clean, safe, and navigable.

This is another reason why obfuscation is something that should be done carefully.

DD: As part of your artistic practice, you often deploy participatory formats for the audience. Lately, though, you seem to be more and more interested in having the audience take a stance and become more involved in the decision-making or problem-solving process. What made you turn in this direction for this particular project? How does user participation become an indispensable part of the work?

PC: I follow the natural evolution of the Internet. I started research works involving millions of individuals in early 2009 when I noticed how quickly Facebook was becoming popular, thus offering a huge audience for my work, which became the actual material of it. Many apps let us manage our life and everything around it by tapping buttons on screens. At this point, everyone makes decisions on the Internet that affects someone else as they produce changes in concrete reality. The Internet is the best tool and environment for decision-making and problem-solving today. Therefore, the basic sense of civility we developed in the physical space should be learned in the online environment.

Yet, with the Internet, we are in the Paleolithic Period, almost naked in public, and learning about what we can do with primitive tools while not knowing how to live together peacefully and with respect for one another.

In this project, I examine online judgment. The rating that is taken to its extreme is online shaming. I’m interested in the ethics and aesthetics around it concerning algorithms and individuals who rate and score others.

With the participatory model proposed, everyone can decide to keep or remove an individual criminal record. I like to invent systems of participation, as they can be structured to channel flows of social dynamics for creative forms of society.

It is a preposition, “what if” everyone could judge people online accused of a crime like an open jury and give a verdict on whether they should be forgiven or punished by society. The project also questions the necessary information to make a fair judgment. I’d not be surprised if tribunals were to one day have this type of online public forum.

DD: Through your artwork, you are underlining the urge for the ‘Right to Remove.’ How does this differ from what we know in Europe as the ‘Right to be Forgotten?

PC: The Right to Be Forgotten has been largely contested in both the U.S. and the E.U. for its potential to censure, for its lack of transparency on the decision process, and because it makes search engines the only jury on what the public can find online. Yet, in the E.U., although not perfect, the law offers all European citizens some rights since a few years ago.

In the U.S., it’s more complicated, mainly because the First Amendment protecting the Freedom of Expression is supposed to win over any attempt to curb the publishing of public information and opinions. This is the case made to oppose the Right to Be Forgotten in the U.S., and the one pushed forward by many organizations, like those dedicated to lobbying for freedom of the press or governmental transparency laws, that still defend the publishing of mugshots.

The federal system in the U.S. further complicates this situation. Every state in the U.S. has been approaching issues concerning the online publication of mugshots, revenge porn, and even information on minors differently. In many states, these are still totally unregulated. Talking about the legal and justice system in the U.S. is very hopeless when considering that Google is the company that has spent the most money ever in lobbying the U.S. Congress. Google has always been strongly opposed to the Right to Be Forgotten in both the E.U. and the U.S. They always mention censorship, technical impracticality, and not being accountable for their search results.

However, with copyright and trademark claims, search engine companies can manage huge quantities of takedown requests. Why would they not be able to offer the same for personal information complaints? Ownership rights should not be more important than human rights.

With this project, I made a proposal for a basic list of very specific categories of personal information that ordinary people in the U.S. should be able to remove from search results. With the Right to Remove, I wanted to create a straightforward campaign to inspire a workable form of this right for the U.S. To do so, I researched this legal subject on the campaign’s website. I launched a petition that I plan to have signed by a few key privacy lawyers, academics, and organizations in the U.S. in the coming months, to be finally presented as an open letter to search engine companies and the FTC. However, for me, this proposal is part of the conceptual artwork. I don’t have hopes of being able to effect change as that would require a huge press effort, and so far, I haven’t received any funding or institutional support for this project.

DD: Are you also interested in the aesthetic qualities of obfuscation? Are you planning a physical installation of the artwork?

For me, the aesthetic qualities are mainly conceptual and strategic.

In most of my work, there is also a documentative function, in this case, it’s about bringing attention to mass incarceration and the lack of a privacy policy in the U.S. Because of the research presenting facts with videos, texts, data, and images, the audience can enjoy the artwork as an interactive documentary. I don’t find data visualization an interesting mode of presentation. Still, I did use the database to find gross human rights violations like the mugshots of ten-year-old kids or seniors over ninety-five.

I later realised that the algorithm that manipulates the mugshots created very interesting visual effects. It seems worth it to make prints of them for the installation. The darkness and the blueness recall the obfuscation of data in a visual form. They look scarier or more inoffensive when the colours hide their appearance. This reminds the audience of how difficult it can be to judge someone without having clear and complete information about the individual. In the installation, I would have a paper shredder that destroys mugshots as they are printed based on the audience’s browsing and interactions on the mugshot websites.

With this project, I also suggest a form of Internet social art practice. It’s inspired by many artists I admire that have been doing social practice work in the U.S. In this case, I’m suggesting that artists can make Internet artworks that have a social function for a problematic group of people, communities and the environment.

For instance, with this project, I started to receive an increasing number of emails from people asking me to remove their records because they thought I was behind the real mugshot websites. They are automatically redirected to sign the petition.

What makes an aesthetic difference for me is when artworks live outside the art world and artistic modes of representation. My audience is not really the minority attending the spectacle of art. Instead, it’s real people with real lives and concerns. Even when the artwork is not exhibited, reviewed, or sold, it’s still online, informing, producing reactions, and possibly changing.

project website: https://obscurity.online

cloned websites:

http://Jailbase.us

http://Usinq.us

http://Mug-Shots.us

http://JustMugshots.us

http://MugshotsOnline.us

http://BustedMugshots.us

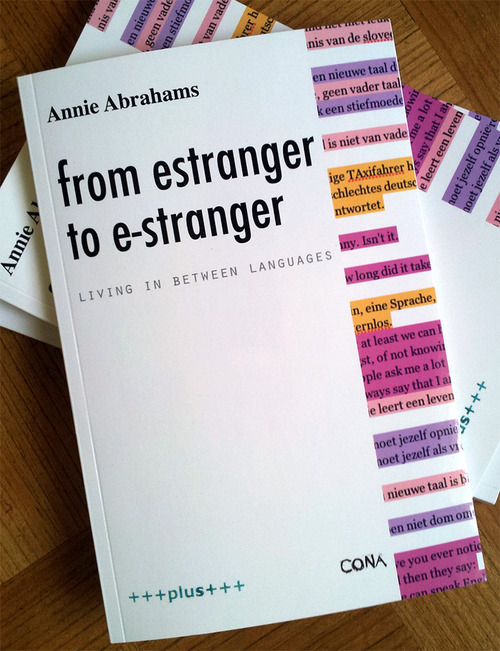

Gretta Louw reviews Abrahams’ book from estranger to e-stranger: Living in between languages, and finds that not only does it demonstrate a brilliant history in performance art, but, it is also a sharp and poetic critique about language and everyday culture.

Annie Abrahams is a widely acknowledged pioneer of the networked performance genre. Landmark telematic works like One the Puppet of the Other (2007), performed with Nicolas Frespech and screened live at the Centre Pompidou in Paris, or her online performance series Angry Women have solidified her position as one of the most innovative net performance artists, who looks not just at the technology itself but digs deeper to discover the ways in which it impacts human behaviour and communication. Even in the present moment, when online performativity is gaining considerable traction (consider the buzz around Amalia Ulman’s recent Instagram project, for example), Abrahams’ work feels rather unique. The strategy is one of contradiction; an intimacy or emotionality of concept and content, juxtaposed against – or, more accurately, mediated through – the technical, the digital, the screen and the network to which it is a portal. Her recent work, however, is shifting towards a more direct interpersonal and internal investigation that is to a great extent nevertheless formed by the forces of digitalisation and cultural globalisation.

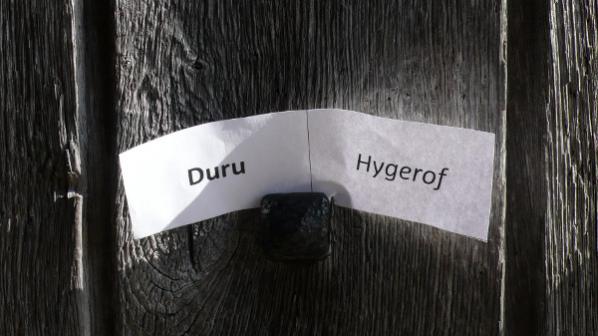

(E)stranger is the title that Abrahams gave to her research project at CONA in Ljubljana, Slovenia, and which led to the subsequent exhibition, Mie Lahkoo Pomagate? (can you help me?) at Axioma. The project is an examination of the shaky, uncertain terrain of being a foreigner in a new land; the unknowingness and helplessness, when one doesn’t speak the language well or at all. Abrahams approaches this topic from an autobiographical perspective, relating this experiment – a residency about language and foreignness in Slovenia. A country with which she was not familiar and a language that she does not speak – regressing with her childhood and young adulthood experiences of suddenly being, linguistically speaking, a fish out of water. This experience took her back to when she went to high school and realised with a shock that, she spoke a dialect but not the standard Dutch of her classmates, and then this situation arose again later when she moved to France and had to learn French as a young adult.

There are emotional and psychological aspects here that are significant and poignant – and ‘extremely’ often overlooked. The way one speaks and articulates oneself is so often equated with intelligence and authority – and thus the foreigner, the newcomer, the language student, is immediately at a disadvantage in the social hierarchy and power distribution. Then, there are the emotional aspects and characteristics requisite for learning a language; one must be willing to make oneself vulnerable, to make mistakes. This is a drain on energy, strength, and confidence that is rarely if ever acknowledged in the current discourse around the EU, migration, asylum seekers, and – that dangerous word – assimilation. Abrahams lays her own experiences, struggles, and frustrations bare in a completely matter-of-fact way, prompting a re-thinking of these commonly held perceptions and exploring the ways that language pervade seemingly all aspects of thought, self, and relationships.

Of course this theme is all the more acute in a world that is increasingly dominated by if not the actual reality of a complete, coherent, and functioning network, then at least the illusion of one. In a world where, supposedly, we can all communicate with one another, there is increasing pressure to do so. Being connected, being ‘influential’ online, representing and presenting oneself online, branding, image – these are factors that are becoming virtues in and of themselves. Silicon Valley moguls like Mark Zuckerberg have spent the last five or six years carefully constructing a language in which online sharing, openness, and connectivity are aligned explicitly with morality. Just one of the many highly problematic issues that this rhetoric tries to disguise is the inherent imperialism of the entire mainstream web 2.0 movement.

Abrahams’ book from estranger to e-stranger: Living in between languages is the analogue pendant to the blog, e-stranger.tumblr.com, that she began working on as a way to gather and present her research, thoughts, and documentation from performances and experiments during her residency at CONA in April 2014 and beyond. Her musings on, for instance, the effect dubbing films and tv programs from English into the local language, or simply screening the English original – how this seems to impact the population’s general fluency in English – raise significant questions about the globalisation of culture. And the internet is arguably even more influential than tv and cinema were/are because of the way it pervades every aspect of contemporary life.

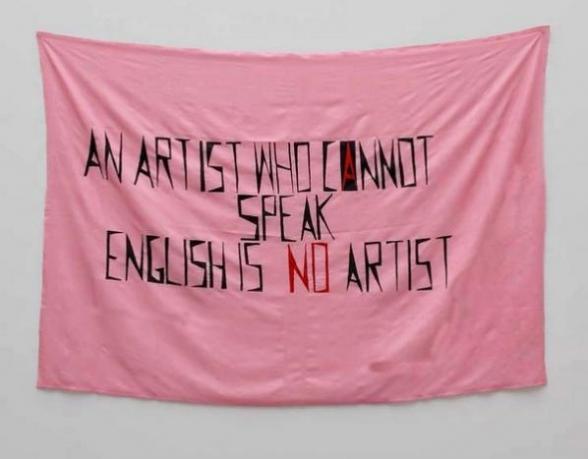

This leads one irrevocably to consider the digital colonialism of today’s internet; the overwhelming dominance of western, northern, mainstream, urban, and mostly english-speaking people/systems/cultural and power structures. [1] Abrahams highlights the way that this bleeds into other areas of work, society, and cultural production, for example, through her citation of Mladen Stilinovic’s piece An Artist Who Cannot Speak English is No Artist (1994). In a recent blog post, Abrahams further reveals the systematic inequity of linguistic imperialism and (usually English speakers’) monolingualism, when she delves into the language politics of the EU and its diplomacy and parliament [http://e-stranger.tumblr.com/post/139842799561/europe-language-politics-policy].

from estranger to e-stranger is an almost dadaist, associative, yet powerful interrogation of the accepted wisdoms, the supposed logic of language, and the power structures that it is routinely co-opted into enforcing. It is a consciously political act that Abrahams publishes her sometimes scattered text snippets – at turns associative or dissociative – in a wild mix of languages, still mostly English, but unfiltered, unedited, imperfect. A rebellion against the lengths to which non-native speakers are expected to go to disguise their linguistic idiosyncrasies (lest these imperfections be perceived as the result of imperfect thinking, logic, intelligence). And yet there is an ambivalence in Abrahams’ intimations about the internet that reflect the true complexity of this cultural and technological phenomena of digitalisation. Reading the book, one feels a keen criticism that is justifiably being levelled at the utopian web 2.0 rhetoric of democratisation, connection etc, but there are also moments of, perhaps, idealism, as when Abrahams asks “Is the internet my mother of tongues? a place where we are all nomads, where being a stranger to the other is the status quo.”

Abrahams’ project is timely, especially now that we are all (supposedly) living in an infinitely connected, post-cultural/post-national, online society, we are literally “living between languages”. The book is an excellent resource, because it is not a coherent, textual presentation of a thesis; of one way of thinking. It is, like the true face of the internet, a collection, a sample, of various thoughts, opinions, ideas, and examples from the past. One can read from estranger to e-stranger cover to cover, but even better is to dip in and out, and or to follow the links and different pages present, and be diverted to read another text that is mentioned, to return, to have an inspiration of one’s own and to follow that. But to keep coming back. There is more than enough food for thought here to sustain repeated readings.

Featured Image: Olia Lialina, My Boyfriend Came Back From The War, at MU. Photo Boudewijn Bollmann

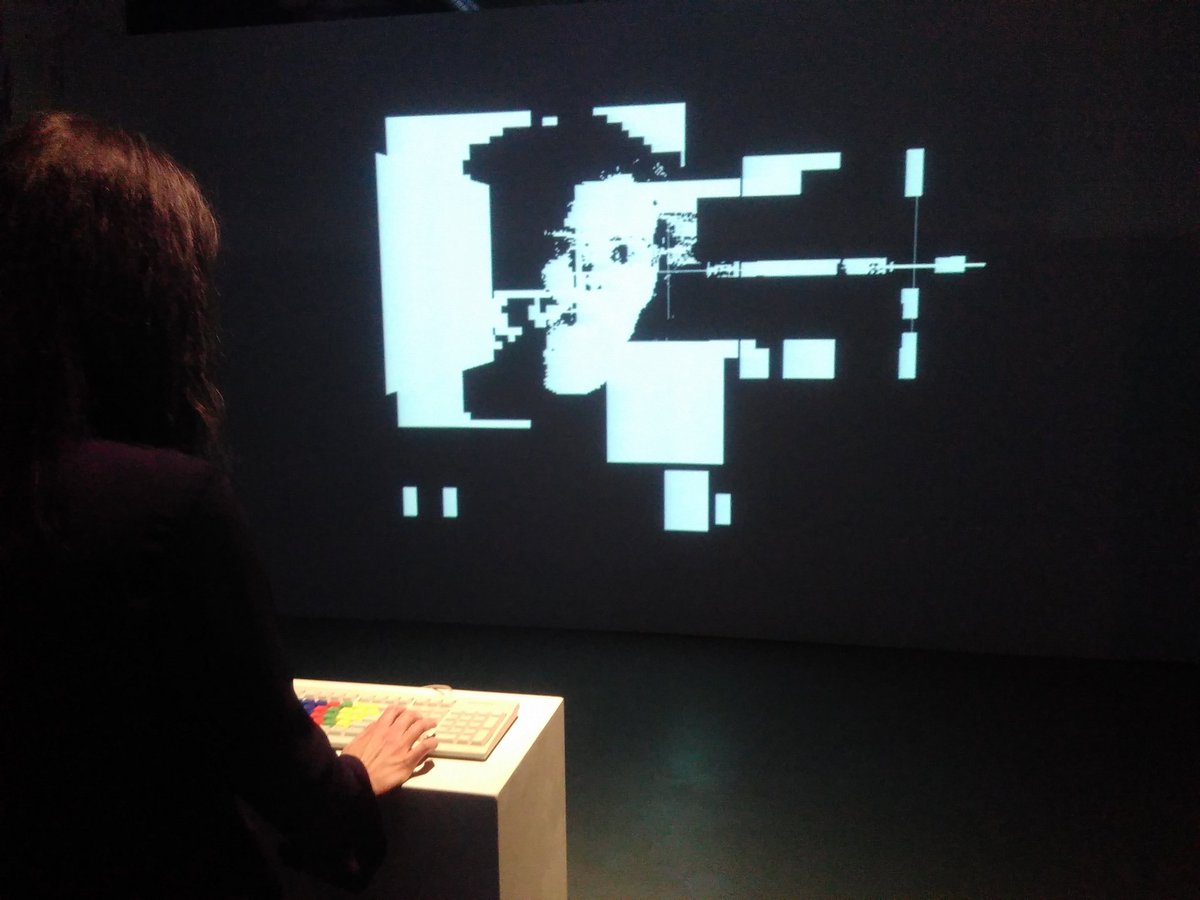

Twenty years ago, in 1996, Russian artist Olia Lialina created My Boyfriend Came Back From The War (MBCBFTW). Using the story of a veteran’s girlfriend who has mixed feelings when he returns, the interactive Web narrative quickly became an iconic work that inspired many artists to create their own interpretations of it. At the moment two exhibitions at HEK in Basel and MU in Eidhoven, pay hommage to MBCBFTW, a tribute to a medium and a new approach to keeping history alive.

Participating artists

Inbal Shirin Anlen, Freya Birren (Jennifer Walshe), Vadim Epstein, Dragan Espenschied, JODI, Olia Lialina, Abe Linkoln, Guthrie Lonergan, Armin Medosch, Ignacio Nieto, Anna Russett, Tale of Tales a.k.a. Entropy8Zuper!, Mark Wirblich. With two new works by Constant Dullaart and Foundland (commissioned by MU).

Educated as a journalist and film critic, and curating experimental film programmes in Moscow, in the mid-1990s Olia Lialina quickly embraced the Web and started experimenting with its unique qualities. She made her first net art piece, My Boyfriend Came Back From The War in 1996. Four years later she set up the Last Real Net Art Museum – an initiative to oppose museums that were presenting the first ‘Internet art exhibitions’, and a place on the Web where she could collect and exhibit the projects that responded to MBCBFTW. Ten years after she made her first net artwork, in 2006, in their popular book New Media Art (Taschen) Mark Tribe and Reena Jana wrote about MBCFTW: ‘One indicator of the historical significance of Olia Lialina’s 1996 Net art project, My Boyfriend Came Back From the War, is the numerous times it has been appropriated and remixed by other New Media artists. (…) Perhaps it resonates with other artists because it is among the earliest works of New Media art to produce the kind of compelling and emotionally powerful experience that we have come to expect from older, more established media, particularly film.’

In the meantime, Lialina had moved on and in addition to her online art practice, wrote about new media, Digital Folklore, the vernacular Web, co-founded the Geocities Research Institute, and became an animated GIF model and a professor at Merz Academy in Stuttgart, whilst the ‘mini-drama in hypertext’ MBCBFTW continued to be of interest to many artists, curators and critics. For its fifteenth anniversary, The Creators Project described MBCBFTW as a ‘charmingly simple yet poignant work’, emphasising its importance for the history of net art and its longevity through its interpretations. At the moment, as Lialina tells me, the project is discussed on Twine – an open source tool for telling interactive, nonlinear stories – where people communicate with each other about this ‘early Twine’. It is therefore not surprising that 2016 starts with two anniversary exhibitions, opening almost at the same time but in different frames, of My Boyfriend Came Back From The War. online since 1996. In what follows I asked Olia Lialina to reflect on the lasting popularity of the work, her intentions for making it, and her ideas about ways to go forward with it.

Can you tell me something about your background, how did you end up being an artist and a professor?

Twenty years ago I was absolutely happy with what I did: writing about films, curating film programmes, trying to make my own films. But as with many who embrace the World Wide Web (or were embraced by it) when it left academia in the mid-1990s – I was lucky to have a sudden new life and career. I became an artist only because MBCBFTW became a piece of net art. And I could become a professor four years later because of it 🙂

Could you briefly describe what the work is about?

In my teens I came up with the sentence ‘My boyfriend came back from the war, after dinner they left us alone.’

Мой парень вернулся с войны

И вот мы остались одни

And I always wanted to complete it as a poem, but the next lines never came. Years later, still confused about the phrase, I made it into an ambivalent dialogue with the browser: dividing it into frames. It was never about a war, but about a difficult conversation that doesn’t lead anywhere, and of course about the browser. I wanted to make something that people would spend time with and look at in the browser. This was also possible back then because the connection was much slower – so it took time to go through it. This has changed a lot now: HTML adapts to faster speeds, and most of us aren’t used to waiting – or loading time – anymore. You cannot click slowly if something is fast. That is also why we artificially slowed down the Internet connection for the exhibition.

When you started working on the Web, you came from a background in journalism and film. What sparked your interest in HTML frames?

They were very new at the time, not every browser supported them and you had to install the Netscape 3 version that had just been released – although in specifications I see now that it also worked in Netscape 2, but I remember that it didn’t back then. So, at the time it was cutting-edge technology – even though there was already a ‘I-hate-frames’ movement on the net, which I only discovered later. For me, it was interesting to see that a browser window could be divided up: you could assign coordinates, partition the screen and have multiple HTML documents within the same window. It sounds naive now, but at the time it was very empowering: I felt like a hacker, I could decide what it looked like and how it functioned.

And it reminded me of celluloid. I used to work with experimental 16mm film: cutting and pasting frames together. The editing was a way to work with the material, not just a concept. So, the connection between film and browser frames was something exciting. At the time I always talked about MBCBFTW as a net film. Someone more familiar with CD-ROM art, programming or interactive art would probably see it differently, but for me using frames inside the browser was a way to edit – it was a direct transition from being a filmmaker to a net artist.

While preparing the inventory table with all the elements of MBCBFW for the exhibition and reviewing the HTML code, I saw so many mistakes that I felt a bit ashamed. Mona Ulrich, one of my students, and I noticed warning after warning while reading through the code. So, it’s not only an old code, it is also very buggy, but despite all that it still works! That is the great thing about HTML, it has a very high tolerance, and it’s very forgiving if you write ‘bad’ code. It allows you to make mistakes: it’s not even that it was easy to learn, but rather that you didn’t really have to learn it at all.

In 2000 you started the Last Real Net Art Museum, as an initiative to collect and present interpretations of MBCBFTW. Could you explain the context and purpose of the Last Real Net Art Museum?

The Last Real Net Art Museum was a provocation to museums who in the late 1990s and early 2000s started making their own online net art exhibitions and collections – and at first they seemed to succeed, but it turned out they didn’t. In my title, ‘Real’ meant that an online collection should be based on links, because the net was about making links to people, information, etc. A good example was äda ’web designed by Vivian Selbo and curated by Benjamin Weil for the Walker Art Centre in Minneapolis between 1995 and 1998. Because this and other projects ended, another phenomenon started with museums like the Guggenheim, Tate and Whitney who acquired copies of Internet art and just kept these somewhere on a floppy or a CD, or showed the work in a pop-up window on their website – for me this was not real, and rather disrespectful of the artworks. And ‘Last’ meant that this previous method was completely disappearing.

The Last Real Net Art Museum was also sort of self-referential because of the First Real Net Art Gallery that I made in 1998, where I sold net art. It wasn’t a gallery selling offline art online, but people could buy online art for the first time. Since the First gallery was still well known in 2000, and to make the connection between the works, the second one became the Last…

Talking about museums and collections, was MBCBFTW ever acquired?

Yes, there is a copy at Telepolis, which was sold for what I thought back then was the amazing sum of 300 German Marks, but it was above all a statement. It’s also in a museum collection, MEIAC (http://www.meiac.es/) in Spain, and has been bought by a private collector, too. There is one more edition left. For this one I think it makes sense to sell the complete package: a computer, a monitor with the right resolution (800 x 600) a slowed-down server connection, an emulator with the old Netscape browser and all the other settings. Everything is emulated, simulated and fake, but the work is alive in its most precious state.

I have also adapted the work at certain times, for example around 2006 I added Google Ads to the website, not to become rich, but to reflect the Web of that time. Without the Ads it seemed old-fashioned and I wanted it to be alive and contemporary. About a year ago I removed them, because they made the work look outdated. It was interesting to see what Google thought suited the site – mostly non-governmental sites. Unfortunately, I never captured this version. That’s the irony – part of me is very much involved in preserving the Web, but when it’s about my own work, I change things immediately and forget how it was before.

The adaptations to the medium are striking in all the different interpretations. Seeing all the works next to each other illustrates a historical technical lineage of online practices: from HTML frames to blogs, games, video and VR. In a sense the Web seems almost to be little more than a constantly changing technical environment. Many have argued that this emphasis on medium specificity is one of the reasons why it took/is taking so long for net art to be taken seriously by the traditional art worlds. How do you view the relationship between the concept and the technical or formal aspects of the work?

For me the main concept and message of the work is the medium specificity. When thinking about the MBCBFTW exhibition we noticed now that it is also about the development of the Web. Yes, it has many technical translations. For example, the work by Auriea Harvey and Michaël Samyn (previously known as Entropy8Zuper!) was made in Flash; it was interactive and had sound, and for that time it was the most obvious software to use. Then Blog and Twitter versions were made, people kept changing it to other realities of the Web. What is interesting though is that the last interpretation, by Inbal Shirin Anlen, brought it back to its original classic HTML structure. The variations are some sort of tribute to the medium: these can range from manifestations of particular elements, to an aesthetic message or a personal statement in the medium.

I strongly believe that there is no contradiction between medium specificity and a mature conceptual message. For that reason I also think that it’s important to always emphasise how the work is made – it just being ‘art’ is not enough; I cannot forget about the Web or the net. In my article ‘Flat against the Wall’ of 2007, I wrote that while it is fine that Web art is part of the art market now, it would be a tragedy if we lost its connection to the Web. It can be a topic of contemporary art but it should stay part of the new media art scene.

For the exhibition you choose specific interpretations. What were your criteria for this selection?

We had to make a selection because some things have been lost. At the time of the Last Real Net Art Museum I thought it was important to just have the links to the works rather than showing copies of the works. So, unfortunately now some works are missing because nobody saved them, the Internet Archive didn’t capture them, and the artists (some of them students at the time) said they didn’t have their work anymore. For example, Web comics were popular at the beginning of the century and someone made a version in that style, which unfortunately didn’t survive either.

In the exhibition we left out works that had a similar structure, but almost all of them are featured in the book that was made for the show by House of Electronic Arts (HeK) in Basel, for example, Don Quichote Came Back From The War (2006) by santo_file group. But we also left some out of the exhibition that – perhaps surprisingly – were just too difficult to show such as the beautiful animated gif by Mike Konstantinov. He made this animated gif in 2000 and it was widely used for and known as a website banner. This work was a typical banner, 468 x 60 in size, and because it doesn’t use any of the images from the original work is also mimicked the cheesiness of banners. In the book it is printed frame-by-frame, but it’s difficult to show the banner phenomenon in an exhibition. We thought of several ways: put it on a random website, or against a black background, but in the end we decided not to present it at all. It just didn’t work.

Another example that isn’t included in the exhibition is Roman Leibov’s work. Leibov is the unofficial father of the Russian Internet. In the mid-1990s the Web in Russia had a strong literary tradition, it was all about games with words and meaningful and innovative hypertexts, including of course many references to Russian literature. I made MBCBFTW in English to intentionally distance myself from this tradition. I wanted to create something very formal because I’m very interested in the structures of the browser, the frames, etc. Had I made it in Russian it would have ended up in a different culture. At the time it was a massive effort, because English wasn’t my language. Then I asked Roman Leibov to make a text version and post it on the Russian Internet, which he did. He took every frame and described it like a film critic, and it ends with a monologue, making it into a piece of literature.

How do you see this type of approach now? To me at times it seems there is much less experimentation with templates or in the browser.

Yes, it’s more difficult to be curious now. The browser is still generous, you can open the source code and look at it, but it’s very complicated to change the code, if you can do it at all. The gap between people looking at and those making the pages has become enormous now. At the time it was easy to copy and modify other people’s pages, but now it is much more difficult to do this.