Featured image: Rosa Menkman, iRD patch, (2015) Black on black embroidered logo [iRD] Encryption key to the institutions RLE 010 0000 – 101 1111

In the lead-up to her solo show, institutions of Resolution Disputes [iRD], at Transfer Gallery, Brooklyn, Daniel Rourke caught up with Rosa Menkman over two gallons of home-brewed coffee. They talked about what the show might become, discussing a series of alternate resolutions and realities that exist parallel to our daily modes of perception.

iRD is open to visitors on Saturdays at Transfer Gallery until April 18th, and will also function as host to Daniel Rourke and Morehshin Allahyari’s 3D Additivist Manifesto, on Thursday April 16th.

Rosa Menkman: The upcoming exhibition at Transfer is an illustration of my practice based PhD research on resolutions. It will be called ‘institutions of Resolution Disputes’, in short iRD and will be about the liminal, alternative modes of data or information representation, that are obfuscated by technological conventions. The title is a bit wonky as I wish for it to reflect that kind of ambiguity that invokes curiosity.

In any case, I always feel that every person, at least once in their grown-up life, wants to start an institution. There are a few of those moments in life, like “Now I am tired of the school system, I want to start my own school!”; and “Now I am ready to become an architect!”, so this is my dream after wanting to become an architect.

Daniel Rourke: To establish your own institution?

RM: First of all, I am multiplexing the term institution here. ‘institutions’ and the whole setting of iRD does mimic a (white box) institute, however the iRD does not just stand for a formal organization that you can just walk into. The institutions also revisit a slightly more compound framework that hails from late 1970s, formulated by Joseph Goguen and Rod Burstall, who dealt with the growing complexities at stake when connecting different logical systems (such as databases and programming languages) within computer sciences. A main result of these non-logical institutions is that different logical systems can be ‘glued’ together at the ‘substrata levels’, the illogical frameworks through which computation also takes place.

Secondly, while the term ’resolution’ generally simply refers to a standard (measurement) embedded in the technological domain, I believe that a resolution indeed functions as a settlement (solution), but at the same time exists as a space of compromise between different actors (languages, objects, materialities) who dispute their stakes (frame rate, number of pixels and colors, etc.), following rules (protocols) within the ever growing digital territories.

So to answer your question; maybe in a way the iRD is sort of an anti-protological institute or institute for anti-utopic, obfuscated or dysfunctional resolutions.

DR: It makes me think of Donna Haraway’s Manifesto for Cyborgs, and especially a line that has been echoing around my head recently:

“No objects, spaces, or bodies are sacred in themselves; any component can be interfaced with any other if the proper standard, the proper code, can be constructed for processing signals in a common language.”

By using the terms ‘obfuscation’ and ‘dysfunction’ you are invoking a will – perhaps on your part, but also on the part of the resolutions themselves – to be recognised. I love that gesture. I can hear the objects in iRD speaking out; making themselves heard, perhaps for the first time. In The 3D Additivist Manifesto we set out to imagine what the existence of Haraway’s ‘common language’ might mean for the unrealised, “the powerless to be born.” Can I take it that your institute has a similar aim in mind? A place for the ‘otherwise’ to be empowered, or at least to be recognised?

RM: The iRD indeed kind of functions as a stage for non-protocological resolutions, or radical digital materialism.

I always feel like I should say here, that generally, I am not against function or efficiency. These are good qualities, they make the world move forward. On the other hand, I do believe that there is a covert, nepotist cartel of protocols that governs the flows and resolutions of data and information just for the sake of functionality and efficiency. The sole aim of this cartel is to uphold the dogma of modern computation, which is about making actors function together (resonate) as efficiently as possible, tweaking out resources to maximum capacity, without bottlenecks, clicks, hicks or cuts, etc.

But this dogma also obfuscates a compromise that we never question. And this is where my problem lies: efficiency and functionality are shaping our objects. Any of these actors could also operate under lower, worse or just different resolutions. Yet we have not been taught to see, think or question any of these resolutions. They are obfuscated and we are blind to them.

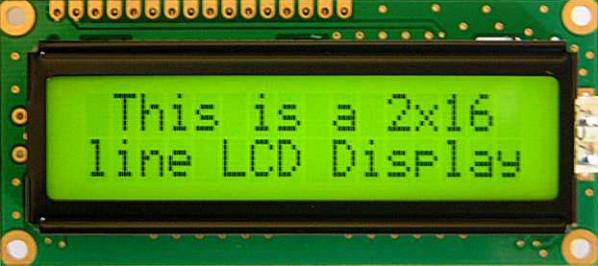

I want to be able to at least entertain the option of round video (strip video from its interface!), to write inside non-quadrilateral, modular text editors (no more linear reading!) or to listen to (sonify) my rainbows (gradients). Right now, the protocols in place simply do not make this possible, or even worse, they have blocked these functionalities.

There is this whole alternate universe of computational objects, ways that our data would look or be used like, if the protocols and their resolutions had been tweaked differently. The iRD reflects on this, and searches, if you will, a computation of many dimensions.

DR: Meaning that a desktop document could have its corners folded back, and odd, non standard tessellations would be possible, with overlapping and intersecting work spaces?

RM: Yes! Exactly!

Right now in the field of imagery, all compressions are quadrilateral, ecology dependent, standard solutions (compromises) following an equation in which data flows are plotted against actors that deal with the efficiency/functionality duality in storage, processing and transmission.

I am interested in creating circles, pentagons and other more organic manifolds! If we would do this, the whole machine would work differently. We could create a modular and syphoning relationships between files, and just as in jon Satroms’ 2011 QTzrk installation, video would have multiple timelines and soundtracks, it could even contain some form of layer-space!

DR: So the iRD is also a place for some of those alternate ‘solutions’ that are in dispute?

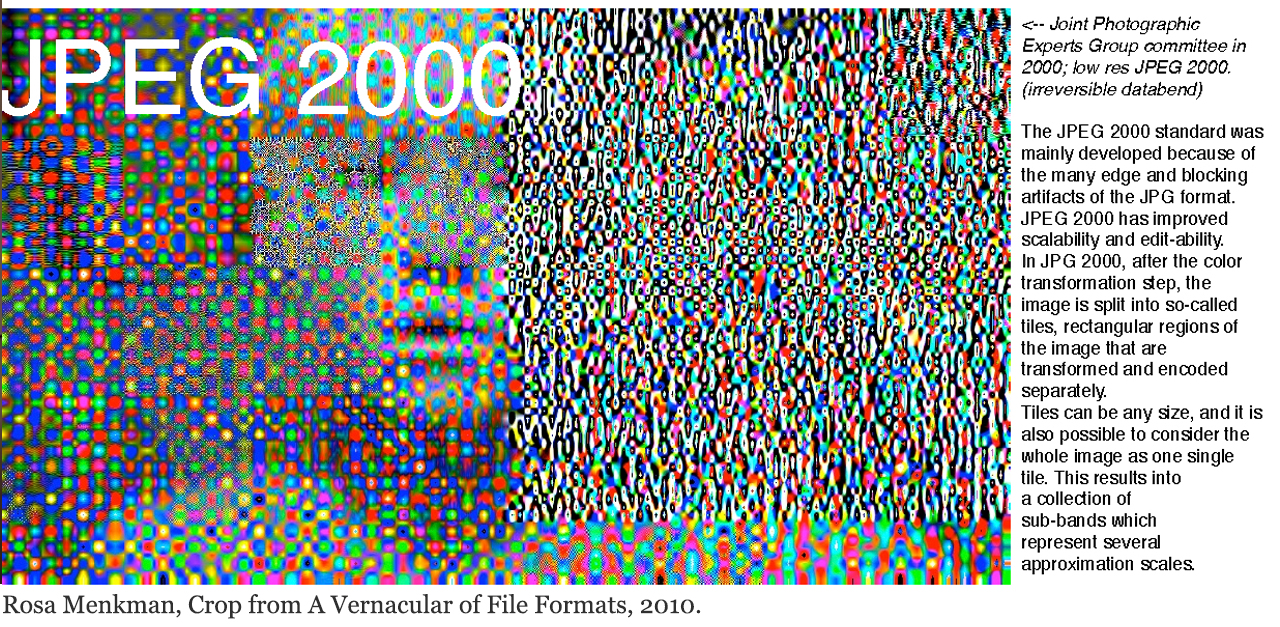

RM: Absolutely. However, while I am not a programmer, I also don’t believe that imagining new resolutions means to absolve of all existing resolutions and their inherent artifacts. History and ecology play a big role in the construction of a resolution, which is why I will also host some of my favorite, classic solutions and their inherent (normally obfuscated) artifacts at the iRD, such as scan lines, DCT blocks, and JPEG2000 wavelets.

The iRD could easily function as a Wunderkammer for artifacts that already exist within our current resolutions. But to me this would be a needles move towards the style of the Evil Media Distribution Center, created by YoHa (Matsuko Yokokoji and Graham Harwood) for the 2013 Transmediale. I love to visit Curiosity Cabinets, but at the same time, these places are kind of dead, celebrating objects that are often shielded behind glass (or plastic). I can imagine the man responsible for such a collection. There he sits, in the corner, smoking a pipe, looking over his conquests.

But this kind of collection does not activate anything! Its just ones own private boutique collection of evil! For a dispute to take place we need action! Objects need to have – or be given – a voice!

DR: …and the alternate possible resolutions can be played out, can be realised, without solidifying them as symbols of something dead and forgotten.

RM: Right! It would be easy and pretty to have those objects in a Wunderkammer type of display. Or as Readymades in a Boîte-en-valise but it just feels so sad. That would not be zombie like but dead-dead. A static capture of hopelessness.

DR: The Wunderkammer had a resurgence a few years ago. Lots of artists used the form as a curatorial paradigm, allowing them to enact their practice as artist and curator. A response, perhaps, to the web, the internet, and the archive. Aggregated objects, documents and other forms placed together to create essayistic exhibitions.

RM: I feel right now, this could be an easy way out. It would be a great way out, however, as I said, I feel the need to do something else, something more active. I will smoke that cigar some other day.

DR: So you wouldn’t want to consider the whole of Transfer Gallery as a Wunderkammer that you were working inside of?

RM: It is one possibility. But it is not my favorite. I would rather make works against the established resolutions, works that are built to break out of a pre-existing mediatic flow. Works that were built to go beyond a specific conventional use.

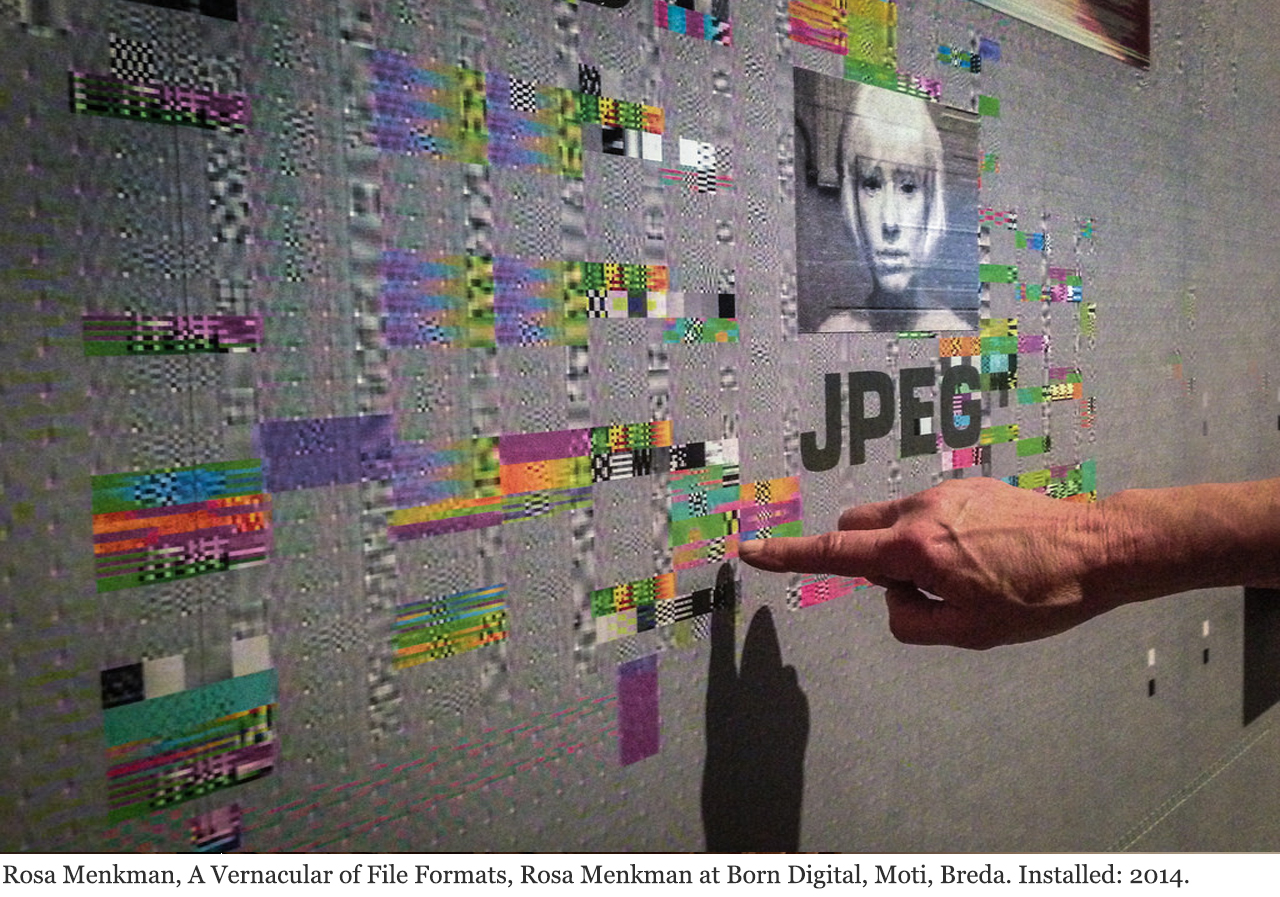

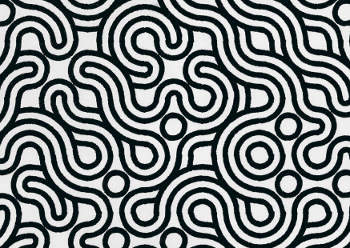

For example, I recently did this exhibition in The Netherlands where I got to install a really big wallpaper, which I think gained me a new, alternative perspectives on digital materiality. I glitched a JPEG and zoomed in on its DCT blocks and it was sooo beautiful, but also so scalable and pokable. It became an alternative level of real to me, somehow.

DR: Does it tesselate and repeat, like conventional wallpaper?

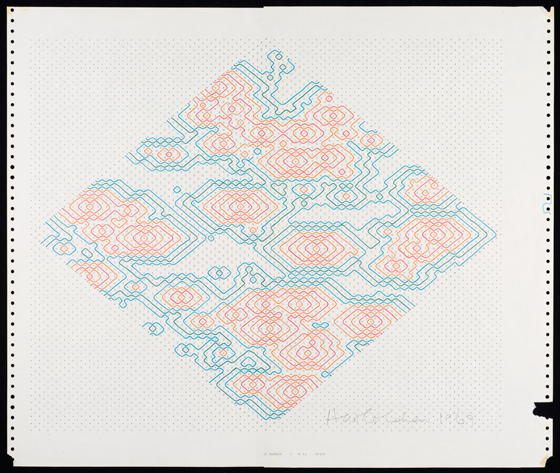

RM: It does repeat in places. I would do it completely differently if I did it again. Actually, for the iRD I am considering to zoom into the JPEG2000 wavelets. I thought it would be interesting to make a psychedelic installation like this. It’s like somebody vomited onto the wall.

DR: [laughs] It does look organic, like bacteria trying to organise.

RM: Yeah. It really feels like something that has its own agency somehow.

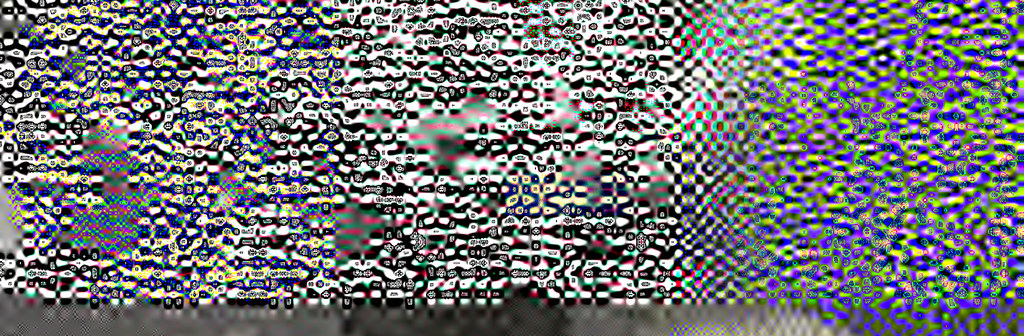

DR: That’s the thing about JPEG2000 – and the only reason I know about that format, by the way, is because of your Vernacular of File Formats – the idea that they had to come up with a non-regular block shape for the image format that didn’t contradict with the artifacts in the bones and bodies that were being imaged. It feels more organic because of that. It doesn’t look like what you expect an image format to look like, it looks like what I expect life to look like, close up.

RM: It looks like ‘Game of Life’.

DR: Yes! Like Game of Life. And I assume that now they don’t need to use JPEG2000 because the imaging resolution is high enough on the machines to supersede bone artifacts. I love that. I love the effect caused when you’ve blown it up here. It looks wonderful. What is the original source for this?

RM: I would blow this image [the one from A Vernacular of File Formats] up to hell. Blow it up until there is no pixel anymore. It shouldn’t be too cute. These structures are built to be bigger. Have you seen the Glitch Timond (2014)? The work itself is about glitches that have gained a folkloric meaning over time, these artifact now refer to hackers, ghosts or AI. They are hung in the shape of a diamond. The images themselves are not square, and I can install them on top of the wallpaper somehow, at different depths. Maybe I could expand on that piece, by putting broken shaped photos, and shadows flying around. It could be beautiful like that.

DR: It makes me think of the spatiality of the gallery. So that the audience would feel like they were inside a broken codec or something. Inside the actual coding mechanism of the image, rather than the standardised image at the point of its visual resolution.

RM: Oh! And I want to have a smoke machine! There should be something that breaks up vision and then reveals something.

DR: I like that as a metaphor for how the gallery functions as well. There are heaps of curatorial standards, like placing works at line of sight, or asking the audience to travel through the space in a particular order and mode of viewing. The gallery space itself is already limited and constructed through a huge, long history of standardisations, by external influences of fashion and tradition, and others enforced by the standards of the printing press, or the screen etc. So how do you make it so that when an audience walks into the gallery they feel as though they are not in a normal, euclidean space anymore? Like they have gone outside normal space?

RM: That’s what I want! Disintegrate the architecture. But now I am like, “Yo guys, I want to dream, and I want it to be real in three weeks…”

DR: “Hey guys, I want to break your reality!” [laughs]

RM: One step is in place, Do you remember Ryan Maguire who is responsible for The Ghost in the MP3? His research is about MP3 compressions and basically what sounds are cut away by this compression algorithm, simply put: it puts shows what sounds the MP3 compression normally cuts out as irrelevant – in a way it inverses the compression and puts the ‘irrelevant’ or deleted data on display. I asked him to rework the soundtrack to ‘Beyond Resolution’, one of the two videowork of the iRD that is accompanied by my remix of professional grin by Knalpot and Ryan said yes! And so it was done! Super exciting.

DR: Yes. I thought that was a fantastic project. I love that as a proposition too… What would the equivalent of that form of ghosting be in terms of these alternate, disputed resolutions? What’s the remainder? I don’t understand technical formats as clearly as you do, so abstract things like ‘the ghost’, ‘the remainder’ are my way into understanding them. An abstract way in to a technical concept. So what is the metaphoric equivalent of that remainder in your work? For instance, I think it depends on what this was originally an image of. I think that is important.

RM: The previous image of JPEG2000 does not deal with the question of lost information. I think what you are after is an inversed Alvin Lucier ‘Sitting in a Room’ experiment, one that only shows the “generation loss” (instead of the generation left over, which is what we usually get to see or hear in art projects). I think that would be a reasonable equivalent to Ryan Maguires MP3 compression work.

Or maybe Supraconductivity.

I can struggle with this for… for at least two more days. In any case I want the iRD to have a soundtrack. Actually, it would like there to be a spatial soundtrack; the ghost soundtrack in the room and the original available only on a wifi access point.

DR: I’m really excited by that idea of ghostly presence and absence, you know. In terms of spatiality, scan lines, euclidean space…

RM: It’s a whole bundle of things! [laughs] “Come on scan lines, come to the institutions, swim with the ghosts!”

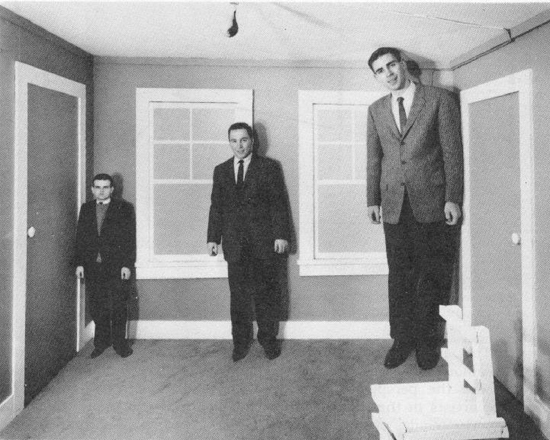

DR: It makes me think of cheesy things you get in a children’s museum. Those illusion rooms, that look normal through a little window, but when you go into them they are slanted in a certain way, so that a child can look bigger than an adult through the window frame. You know what I mean? They play with perspective in a really simple way, it’s all about the framing mechanism, the way the audience’s view has been controlled, regulated and perverted.

RM: I was almost at a point where I was calling people in New York and asked, “Can you produce a huge stained glass window, in 2 weeks?” I think it would be beautiful if the Institute had its own window.

I would take a photo of what you could see out of the real window, and then make the resolution of that photo really crappy, and create a real stained glass window, and install that in the gallery at its original place. If I have time one day I would love to do that, working with real craftspeople on that. I think that in the future the iRD might have a window through which we interface the outside.

Every group of people that share the same ideas and perspectives on obfuscation need to have a secret handshake. So that is what I am actually working on right now. Ha, You didn’t see that coming? [Laughs]

DR: [Laughs] No… that’s a different angle.

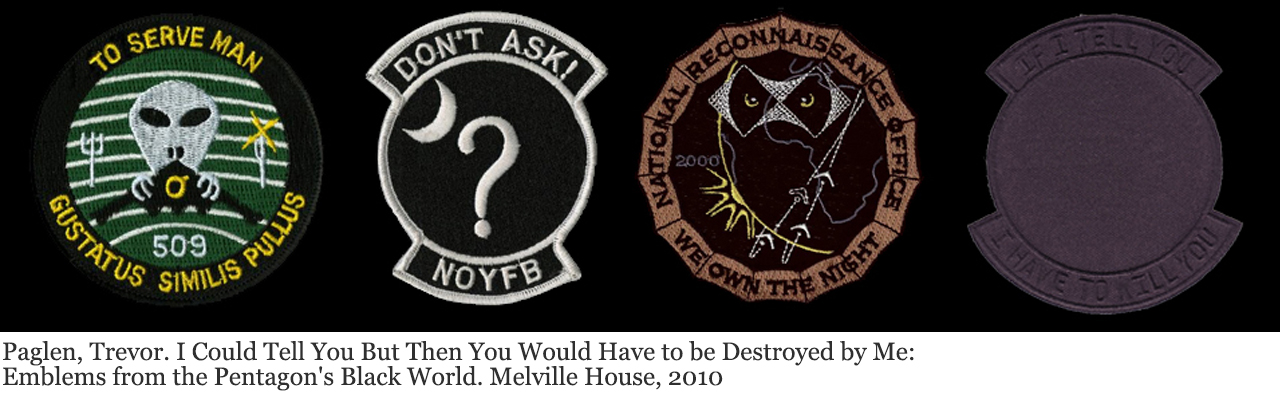

RM: I want people to have a patch! A secret patch. You remember Trevor Paglen’s book on the symbology of military patches?

DR: Oh yeah. Where he tries to decode the military patches? Yes, I love that.

RM: Yeah, I don’t think the world will ever have enough patches. They are such an icon for secret handshakes.

I have been playing around with this DCT image. I want to use it as a key to the institutions, which basically are a manifest to the reasonings behind this whole exhibition, but then encrypted in a macroblock font (I embedded an image of Institution 1 earlier). There was one of Paglen’s patches that really stood out for me; the black on black one. The iRD patch should be inspired by that.

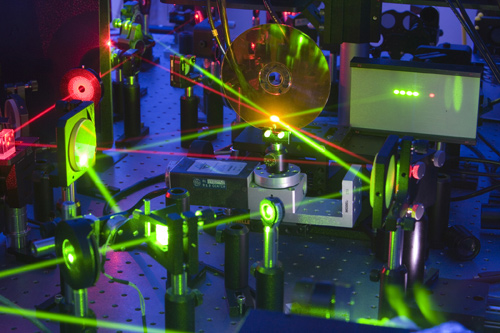

DR: Hito Steyerl’s work How Not to be Seen: A Fucking Didactic Educational .MOV File, centres on the grid used by the military to calibrate their satellites from space. The DCT structure looks a lot like that, but I know the DCT is not about calibration. It contains all the shapes necessary to compose any image?

RM: If you look up close at a badly compressed JPEG, you will notice the image consist of macroblocks. A macroblock is a block organizations, usually consisting of 8×8 pixels, that posses color (chrominance) and light (luminance) values embedded via DCT (discrete cosine transform).

Basically all JPEGs you have ever seen are build out of this finite set of 64 macroblocks. Considering that JPEGs make up the vast majority of images we encounter on a daily basis, I think it is pretty amazing how simple this part of the JPEG compression really is.

But the patch should of course not just be square. Do you know the TV series Battlestar Galactica, where they have the corners cut off all their books? All the paper in that world follows this weird, octagonal shape? Or Borges Library and its crimson hexagon, that holds all knowledge. I love those randomly cryptic geometric forms…

DR: It reminds me of a 1987 anime film, Wings of Honneamise, that had a really wonderfully designed world. Everything is different, from paper sizes and shapes, through to their cutlery. Really detailed design from the ground up, all the standards and traditions.

RM: Like this Minecraft book too. The Blockpedia.

DR: Oh that’s great. I love the Minecraft style

and the mythos that has arisen around it.

RM: So Minecraft and Borges follow a 6 corner resolution, and Battlestar paper has 8 corners… Discrepancy! I want to reference them all!

DR: So these will go into the badges?

RM: I want to have a black on black embroidered patch with corners. Don’t you think this would be so pretty? This black on black. I want to drop a reference to 1984, too, Orwell or Apple, the decoder can decide. These kind of secret, underground references, I like those.

DR: A crypto exhibition.

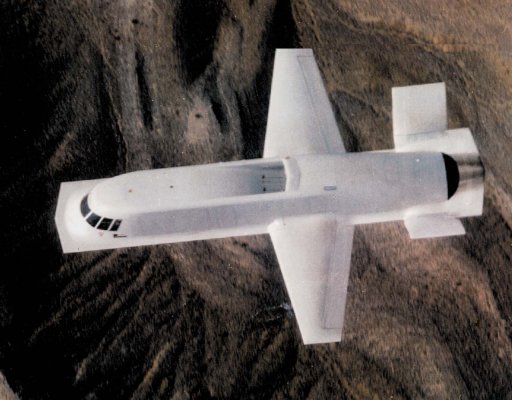

RM: It’s so hot right now (and with hot I do not mean cool). Since the 90s musicians encrypt or transcode things in their sounds, from Aphex Twin, to Goodiepal and now TCF, who allegedly encrypted an image from the police riots in Athens into one of his songs. However, he is a young Scandinavian musician so that makes me wonder if the crypto design in this case is confusingly non-political. Either way, I want to rebel against this apparent new found hotness of crypto-everything, which is why I made Tacit:Blue.

Tacit:Blue uses a very basic form of encryption. Its archaic, dumb and decommissioned. Every flash shows a next line of my ‘secret message’ encrypted in masonic pigpen. When it flickers it gives a little piece of the message which really is just me ranting about secrecy. So if someone is interested in my opinion, they can decode that.

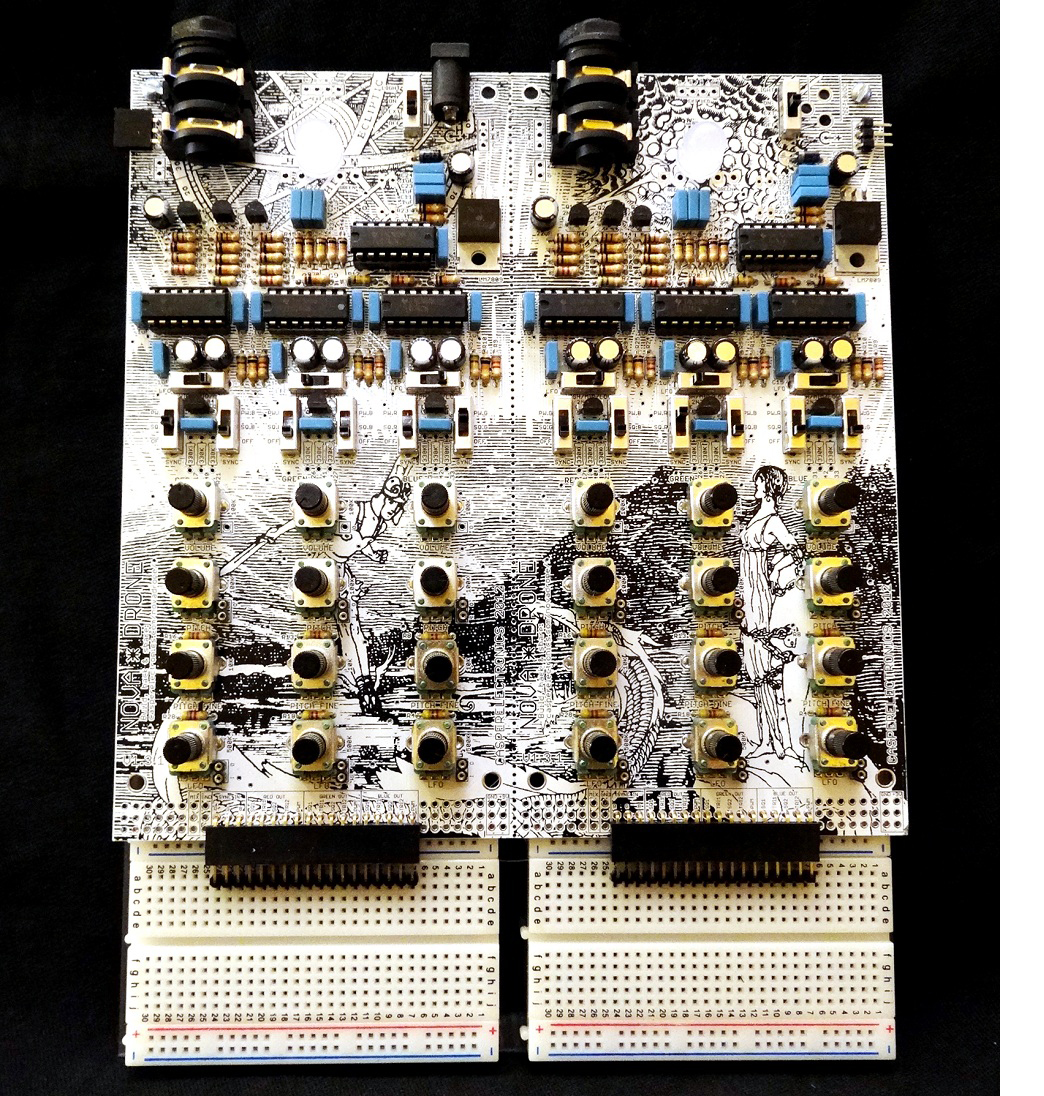

Actually, the technology behind the video is much more interesting. Do you know The Nova Drone? Its a small AV synthesizer designed by Casper Electronics. The the flickr frequency of this military RGB LED on the top of the board can be altered by turning the RGB oscillators. When I come close to the LED with the lens of my iphone, the frequencies of the LED and the iphone camera do not sync up. What happens is a rolling shutter effect. The camera has to interpret the input and something is gone, lost in translation. In fact, a Resolutional Dispute takes place right there.

DR: So the dispute happens because framerate of the camera conflicts with the flicker of the LED?

RM: And the sound is the actual sound of the electronics. In Tacit:Blue I do not use the NovaDrone in a ‘clean’ way, I am actually misusing it (if there is such a thing when it comes to a device of dispute). Some of the sounds and disruptions of flow are created in this patch bay, which is where you can patch the LFOs, etc. Anyway, when you disconnect the patch it flickers, but I never take it out fully so it creates this classic, noisy electric effect.

What do you think about the text? Do you think this works? I like this masonic pigpen, its a very simple, nostalgic old quiff.

DR: It reminds me of the title sequence for Alien. Dave Addey did a close visual, sci-fi etymological, analysis of the typography in Alien. It went viral online recently. Did you see that?

RM: No!

DR: It is fantastic. Everything from the title sequence to the buttons on the control panel in the background. Full of amazing insights.

RM: Wow, inspiring!

So with any cypher you also need a key, which is why I named the video Tacit:Blue, a reference to the old Northrop Tacit Blue stealth surveillance aircraft. The aircraft was used to develop techniques against passive radar detection, but has been decommissioned now, just like the masonic pigpen encryption.

DR: This reminds me of Eyal Weizman. He has written a lot on the Israeli / Palestinian conflict as a spatial phenomena. So we don’t think about territory merely as a series of lines drawn on a globe anymore, but as a stack, including everything from airspace, all the way down beneath the ground, where waste, gas and water are distributed. The mode by which water is delivered underground often cuts across conflicted territories on the surface. A stacked vision of territory brings into question the very notion of a ‘conflict’ and a ‘resolution’.

I recently saw him give a lecture on the Forensic Architecture project, which engages in disputes metered against US Military activities. Military drones are now so advanced that they can target a missile through the roof of a house, and have it plunge several floors before it explodes. It means that individual people can be targeted on a particular floor. The drone strike leaves a mark in the roof which is – and this is Weizman’s terminology – ‘beneath the threshold of detectability’. And that threshold also happens to be the size of a human body: about 1 metre square. Military satellites have a pixel size that effectively translates to 1 metre square at ground level. So to be invisible, or technically undetectable, a strike needs only to fall within a single pixel of a satellite imaging system. These drone strikes are designed to work beneath that threshold.

In terms of what you are talking about in Trevor Paglen’s work, and the Northrop Tacit Blue, those technologies were designed to exist beneath, or parallel to, optic thresholds, but now those thresholds are not optic as much as they are about digital standards and resolution densities. So that shares the same space as the codecs and file formats you are interested in. Your patch seems to bring that together, the analogue pixel calibration that Steyerl refers to is also part of that history. So I wonder whether there are images that cannot possibly be resolved out of DCT blocks. You know what I mean? I think your work asks that question. What images, shapes, and objects exist that are not possible to construct out of this grid? What realities are outside of the threshold of these blocks to resolve? It may even be the case that we are not capable of imagining such things, because of course these blocks have been formed in conjunction with the human visual system. The image is always already a compromise between the human perceptual limit and a separately defined technical limit.

RM: Yes, well I can imagine vector graphics, or mesh based graphics where the lines are not just a connection between two points, but also a value could be what you are after. But I am not sure.

At some point I thought that people entering the iRD could pay a couple of dollars for one of these patches, but if they don’t put the money down, then they would be obliged to go into the exhibition wearing earplugs.

DR: [Laughs] So they’d be allowed in, but they’d have one of their senses dampened?

RM: Yes, wearing earmuffs, or weird glasses or something like that. [Laughs]

DR: Glasses with really fine scan lines on them that conflict with TV images or whatever.

RM: [Laughs] And I was thinking, well, there should be a divide between people. To realise that what you see is just one threshold that has been lifted to only a few. There are always thresholds, you know.

DR: Ways to invite the audience into the spaces and thresholds that are beneath the zones of resolutional detectability?

RM: Or maybe just to show the mechanics behind objects and thresholds.

DR: Absolutely. So to go back to your Tacit:Blue video, in regards the font, I like the aesthetic, but I wonder whether you could play with that zone of detectability a little more.

You could have the video display at a frequency that is hard for people to concentrate on, for instance, and then put the cryptographic message at a different frequency. Having zones that do not match up, so that different elements of the work cut through different disputed spaces. Much harder to detect. And more subliminal, because video adheres to other sets of standards and processes beyond scan lines, the conflict between those standards opens up another space of possibilities.

It makes me think about Takeshi Murata’s Untitled (Pink Dot). I love that work because it uses datamoshing to question more about video codecs than just I and P frames. That’s what sets this work apart, for me, from other datamoshed works. He also plays with layers, and post production in the way the pink dot is realised. As it unfolds you see the pink dot as a layer behind the Rambo footage, and then it gets datamoshed into the footage, and then it is a layer in front of it, and then the datamosh tears into it and the dot become part of the Rambo miasma, and then the dot comes back as a surface again. So all the time he is playing with the layering of the piece, and the framing is not just about one moment to the next, but it also it exposes something about Murata’s super slick production process. He must have datamoshed parts of the video, and then post-produced the dot onto the surface of that, and then exported that and datamoshed that, and then fed it back into the studio again to add more layers. So it is not one video being datamoshed, but a practice unfolding, and the pink dot remains a kind of standard that runs through the whole piece, resonating in the soundtrack, and pushing to all elements of the image. The work is spatialised and temporalised in a really interesting way, because of how Murata uses datamoshing and postproduction to question frames, and layers, by ‘glitching’ between those formal elements. And as a viewer of Pink Dot, your perception is founded by those slips between the spatial surface and the temporal layers.

RM: Yeah, wow. I never looked at that work in terms of layers of editing. The vectors of these blocks that smear over the video, the movement of those macroblocks, which is what this video technologically is about, is also about time and editing. So Murata effectively emulates that datamosh technique back into the editing of the work before and after the actual datamosh. That is genius!

DR: If it wasn’t for Pink Dot I probably wouldn’t sit here with you now. It’s such an important work for me and my thinking.

Working with Morehshin Allahyari on The 3D Additivist Manifesto has brought a lot of these processes into play for me. The compressed labour behind a work can often get lost, because a final digital video is just a surface, just a set of I and P frames. The way Murata uses datamoshing calls that into play. It brings back some of the temporal depth.

Additivism is also about calling those processes and conflicts to account, in the move between digital and material forms. Oil is a compressed form of time, and that time and matter is extruded into plastic, and that plastic has other modes of labour compressed into it, and the layers of time and space are built on top of one another constantly – like the layers of a 3D print. When we rendered our Manifesto video we did it on computers plugged into aging electricity infrastructures that run on burnt coal and oil. Burning off one form of physical compressed time to compress another set of times and labours into a ‘digital work’.

RM: But you can feel that there is more to that video than its surface!

If I remember correctly you and Morehshin wrote an open invitation to digital artists to send in their left over 3D objects. So every object in that dark gooey ocean in The 3D Additivist Manifesto actually represents a piece of artistic digital garbage. It’s like a digital emulation of the North Pacific Gyre, which you also talked about in your lecture at Goldsmiths, but then solely consisting of Ready-Made art trash.

The actual scale and form of the Gyre is hard to catch, it seems to be unimaginable even to the people devoting their research to it; it’s beyond resolution. Which is why it is still such an under acknowledged topic. We don’t really want to know what the Gyre looks or feels like; it’s just like the clutter inside my desktop folder inside my desktop folder, inside the desktop folder. It represents an amalgamation of histories that moved further away from us over time and we don’t necessarily like to revisit, or realise that we are responsible for. I think The 3D Additivist Manifesto captures that resemblance between the way we handle our digital detritus and our physical garbage in a wonderfully grimm manner.

DR: I’m glad you sense the grimness of that image. And yes, as well as sourcing objects from friends and collaborators we also scraped a lot from online 3D object repositories. So the gyre is full of Ready-Mades divorced from their conditions of creation, use, or meaning. Like any discarded plastic bottle floating out in the middle of the pacific ocean.

Eventually Additivist technologies could interface all aspects of material reality, from nanoparticles, to proprietary components, all the way through to DNA, bespoke drugs, and forms of life somewhere between the biological and the synthetic. We hope that our call to submit to The 3D Additivist Cookbook will provoke what you term ‘disputes’. Objects, software, texts and blueprints that gesture to the possibility of new political and ontological realities. It sounds far-fetched, but we need that kind of thinking.

Alternate possibilities often get lost in a particular moment of resolution. A single moment of reception. But your exhibition points to the things beyond our recognition. Or perhaps more importantly, it points to the things we have refused to recognise. So, from inside the iRD technical ‘literacy’ might be considered as a limit, not a strength.

RM: Often the densities of the works we create, in terms of concept, but also collage, technology and source materials move quite far away or even beyond a fold. I suppose that’s why we make our work pretty. To draw in the people that are not technically literate or have no back knowledge. And then perhaps later they wonder about the technical aspects and the meaning behind the composition of the work and want to learn more. To me, the process of creating, but also seeing an interesting digital art work often feels like swimming inside an abyss of increments.

DR: What is that?

RM: I made that up. An abyss is something that goes on and on and on. Modern lines used to go on, postmodern lines are broken up as they go on. Thats how I feel we work on our computers, its a metaphor for scanlines.

DR: In euclidean space two parallel lines will go on forever and not meet. But on the surface of a globe, and other, non-euclidean spaces, those lines can be made to converge or diverge. *

RM: I have been trying to read up on my euclidean geometry.

DR: And I am thinking now about Flatland again, A Romance in Many Dimensions.

RM: Yeah, it’s funny that in the end, it is all about Flatland. That’s where this all started, so thats where it has to end; Flatland seems like an eternal ouroboros inside of digital art.

DR: It makes me think too about holographic theory. You can encode on a 2D surface the information necessary to construct a 3D image. And there are theories that suggest that a black hole has holographic properties. The event horizon of a black hole can be thought of as a flat surface, and contains all the information necessary to construct the black hole. And because a black hole is a singularity, and the universe can be considered as a singularity too – in time and space – some theories suggest that the universe is a hologram encoded on its outer surface. So the future state of the universe encodes all the prior states. Or something like that.

RM: I once went to a lecture by Raphael Bousso, a professor at Department of Physics, UC Berkeley. He was talking about black holes, it was super intense. I was sitting on the end of my seat and nearly felt like I was riding a dark star right towards my own event horizon.

DR: [laughs] Absolutely. I suppose I came to understand art and theory through things I knew before, which is pop science and science fiction. I tend to read everything through those things. Those are my starting points. But yes, holograms are super interesting.

RM: I want to be careful not to go into the wunderkammer, because if there are too many things, then each one of them turns into a fetish object; a gimmick.

DR: There was a lot of talk a few years ago about holographic storage, because basically all our storage – CDs, DVDs, hard drive platters, SSD drives – are 2D. All the information spinning on your screen right now, all those rich polygons or whatever, it all begins from data stored on a two dimensional surface. But you could have a holographic storage medium with three dimensions. They have built these things in the laboratory. There goes my pop science knowledge again.

RM: When I was at Transmediale last year, the Internet Yami-ichi (Internet Black Market) was on. There I sold some custom videos for self cracked LCD screens.

DR: Broken on purpose?

RM: Yes, and you’d be allowed to touch it so the screen would go multidimensional. Liquid crystals are such a beautiful technology.

DR: Yes. And they are a 3D image medium. But they don’t get used much anymore, right? LEDS are the main image format.

RM: People miss LCDS! I saw a beautiful recorded talk from the Torque event, Esther Leslie talking about Walter Benjamin who writes about snow flakes resembling white noise. Liquid crystals and flatness and flatland.

I want to thank you Dan, just to talk through this stuff has been really helpful. You have no idea. Thank you so much!

DR: Putting ideas in words is always helpful.

RM: I never do that, in preparation, to talk about things I am still working on, semi-completed. It’s scary to open up the book of possibilities. When you say things out loud you somehow commit to them. Like, Trevor Paglen, Jon Satrom are huge inspirations, I would like to make work inspired by them, that is a scary thing to say out loud.

DR: That’s good. We don’t work in a vacuum. Trevor Paglen’s stuff is often about photography as a mode of non-resolved vision. I think that does fit with your work here, but you have the understanding and wherewithal to transform these concerns into work about the digital media. Maybe you need to build a tiny model of the gallery and create it all in miniature.

RM: That’s what Alma Alloro said!

DR: I think it would be really helpful. You don’t have to do it in meatspace. You could render a version of the gallery space with software.

RM: Haha great idea, but that would take too much time. iRD needs to open to the public in 3 weeks!

* DR originally stated here that a globe was a euclidean space. This was corrected, with thanks to Matthew Austin.

A Computer in the Art Room: The Origins of British Computer Arts 1950-1980

Catherine Mason

ISBN: 1899163891

JJG Publishing 2008

Computing anywhere else but its history often seems like a carefully guarded secret. This has been alleviated by activity around the resurrected Computer Arts Society in the 2000s, notably the acquisition of CAS’s archives by the V&A and the CaCHE project at Birbeck College which ran from 2002-2005. CaCHE, run by Paul Brown, Charlie Gere, Nick Lambert and Catherine Mason, produced conferences, exhibitions, and publications including the book “A Computer In the Art Room”, by Mason.

The art room of the title is the art department of British educational institutions prior to art becoming a degree-level subject. From the 1950s to the 1970s, when the cost of computing machinery dropped from the level where only major government and corporate organizations could afford them to the level where you only needed a second mortgage to afford one, the best way for artists to get access to the enabling technology of computing machinery was usually in an educational institution.

Mason starts out by describing the artistic and art educational situation in the UK at the time of the Festival Of Britain and the foundation of the ICA in London in the early 1950s. She then explains the structure and significance of the emergence of Basic Design teaching, the impact of the Coldstream report on art education, and the rise of the polytechnic colleges over the next thirty years. This provides vital context for the emergence of art computing teaching in the UK. It is also of more general interest for British art history. Conceptualism, performance, Land Art, the Hornsey Art School occupation, and the educational and media graphics that are currently being used as the basis of “hauntological” art all share this background and can better be understood and critiqued with better knowledge of it.

Basic Design courses started in London but didn’t remain there for long. They spread and matured throughout the UK, becoming entangled with the earliest teaching of art computing in provincial technical colleges. Mason traces the family trees of art computing teaching over time through these institutions and back to London-based institutions. Some of the names are familiar from art history (Richard Hamilton, Stephen Willats), some from art computing history (Harold Cohen, John Latham). Where the people involved cross over with cybernetic art, Conceptualism or other artistic currents Mason shows how their ideas fed into and from their art computing work.

The conceptual content of art computing followed the Bauhaus, cybernetics, systems, sociological and environmental influences on art from the 1950s to the 1970s. Its technological forms likewise followed those of mainstream computing. In the 1960s time was leased on mainframes or computers were built by hand. In the 1970s, minicomputers became available and art domain-specific software frameworks or programming languages were written by their users. In the 1980s, workstations with touch tablets, framebuffers, and increasingly proprietary software brought previously unprecedented power and ease of use at the cost of more fixed forms.

The history that I had to piece together as a student from hearsay and from hints in old publications, of the PICASO graphics language at Middlesex University that I found a print-out of the manual for when I was there in the 1990s, of Art & Language’s use of mainframe computers, of early cross-overs between art computing and dance, of cybernetic systems and games that attracted mass audiences before disappearing, is detailed, illustrated and contextualized in page after page of descriptions of hardware, software, institutions, courses and projects. The detail would be overwhelming where it not for Mason’s ability to bring the human and broader cultural aspect of it all to life.

There’s Jasia Reichardt’s Cybernetic Serendipity show at the ICA, Andy Inakhowitz’s Senster robot, John Latham’s dance notation experiments, The Environment Game, and computer graphics drawn with the languages and environments developed in UK art institutions. There’s pictures of the computer systems at the Slade, the RCA, Wimbledon and other art schools that serve as insights into the artists’ studios. There’s the Computer Arts Society, IRAT, APG. And, crucially, there’s the links between them told in a narrative that is coherent while still presenting the breaks and false starts in the story.

The history of “A Computer In The Art Room” reads all too often as brief moments of individuals triumphing against the odds to produce key works of art computing then fading into obscurity, academia or commerce. But any art history that considers a specific context at such a level of detail will look like this. Mason describes works, institutions and artists that deserve broader recognition, although she is under no illusion about how far the road to that recognition may be, citing the example of how long it has taken for photography to be recognized as art in the culturally conservative UK.

The social and pedagogical changes of the period covered by “A Computer In The Art Room” reflect a time of hope and ambition for education in society that made the academy less remote. Mason provides the social, technological and educational context needed to appreciate the very real achievements of art computing that she describes against this backdrop. As a slice of art history this is richly detailed. It touches on subjects far beyond art computing that will help any art student of history better understand the period covered. And it is both a relief and an inspiration to finally have a public record of this important aspect of the history of art computing in the UK.

The text of this review is licenced under the Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0 Licence.

Decode: Digital Design Sensations

The Victoria and Albert museum, London

8 December 2009 – 11 April 2010

Decode: Digital Design Sensations at the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) brings the state of the art in art computing to a venerable cultural institution. Everything from the posters and banners around town to the hoardings on the entrance to the gallery containing the show makes it clear that Decode is a serious cultural event. It’s a spectacle, a dark space alongside the well-lit galleries of the V&A, drawing you in with points of light and distant sounds. The crowds are reassuring for the popularity of art computing yet disconcerting for the experience of the art at times.

Don’t forget to ask for a catalogue as you hand over your ticket on the way in. The sponsor’s foreword should raise a smile to anyone familiar with the software industry, but the introductory essay (which only occasionally becomes the latest casualty of the confusion that the word “open” shows), the details of works in the show and the interviews with Golan Levin and Daniel Rozin are all very informative. The catalogue also draws attention to Karsten Schmidt’s specially commissioned graphic identity for the show, which can be downloaded and modified as Free Software.

The show is divided into three sections. Generative art, data visualisation, and interactive multimedia (or, as the catalogue puts it – Code, Network and Interactivity).

The generative artworks suffer in comparison to the other pieces by being mostly small-scale screen based pieces. However appealing the images are on the screen (and they are) they cannot compete with the projections and three dimensional installations of the other sections. With the exception of an interactive version of the video to Radiohead’s House of Cards by James Frost and Aaron Koblin, the work does not refer to the human figure or to the viewer, another feature of many of the most popular pieces in the other sections. And apart from Matt Pyke’s typographic totem pole, my other favourite piece of the section, the work is calm. Beautiful, but calm. It would reward prolonged contemplation in a quieter environment and might benefit from presentation on a larger scale to better bring out its aesthetic qualities. But this is not that environment, and that presentation is not given to the work here.

The data visualisation section has more projections and custom hardware, and also has more human interest. The emotion of We Feel Fine by Jonathan Harris and Sep Kamvar, the surveillance state expose of Stanza’s Sensity, CCTV assemblages, Make-Out, the porn-inspired kissing figures of Rafael Lozano-Hemmer and the social data visualizations of Social Collider by Sascha Pohflepp & Karsten Schmidt are sometimes less visually sophisticated than some of the generative pieces, but address current social and technological developments more directly. The world wide web is twenty years old, it has drawn in the mass media and media feeds from the real world, and many of its users produce and encounter gigabytes of data over time. Representing and exploring that technological and cultural environment is something that art can do and that art is particulalry well placed to do given the importance of the aesthetics of interfacing and visualisation to the contemporary web.

The interactive multimedia section contained the real crowd pleasers of the show, although some of the pieces had “out of order” notices on them when I visited. Yoke’s virtual reality Dandelion Clock controlled by a hairdryer, Ross Phillips’s Videogrid, a physically interactive group portrait and Daniel Rozin’s Weave Mirror, a cybernetic sculpture-cum-display-screen. They all give their audience an aesthetic experience that briefly changes their relationship to the world, and in some cases shows them themselves in that new relationship. Interactive multimedia installation is clearly due a resurgence.

The V&A have presented Decode as a design show. I was struck by this framing of the work when I visited the show, and most of the people I have spoken to about the show since have commented on it as well. Many of the participants are graphic designers or work in design as well as art and education, but much of the work would be poorly served by being regarded as design rather than as art. It is not advertising, or presentation of anything other than itself for the most part. Where the work is information design, the information has been chosen by the designer. That said the art computing MA I attended as a student had to be called a “design” course to get funding, so possibly this is a constant. And the V&A have done a great job of presenting the work and letting it speak for itself to the visiting crowds.

This isn’t quite Cybernetic Serendipity 2.0. It excludes the conceptually and performatively, rougher edges of contemporary art computing. But these exclusions are largely practical; there is no livecoding and there are no email or self-contained web browser-based works. Some of the work is strikingly but subtly political in its representation of current social and political trends such as surveillance, online pornography and the death of privacy.

The V&A have done the conventional artworld and the general public a great service by presenting Decode. The show contains enough big and up-and-coming names in art computing and digital design to provide a convincing if necessarily incomplete survey of the contemporary scene. Decode also serves an important role for artists and students with an interest in or a stake in art computing by focussing attention on what others have achieved that can be built on.

Decode shows the achievements of the personal computing and web eras of art computing becoming established with and recognized by the broader arts establishment. The danger is that the story will finish triumphally here. Processing has become the new Shockwave, and particle systems and shape grammars are not enough in themselves for long without an accompanying progressive and deeper deeper engagement with the aesthetics and history of art, technology, wider society, or all three. Art computing is not immune to technical and aethetic conservatism. To avoid this I think that it needs to intensify, to become more like itself; to become more beautiful, to tackle larger datasets, to become more interactive. In other words, it needs to build on the achievements gathered together and presented here.

http://www.vam.ac.uk/exhibitions/future_exhibs/Decode/

The text of this review is licenced under the Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0 Licence.

Digital Pioneers

Victoria And Albert Museum

7 December 2009 – 25 April 2010

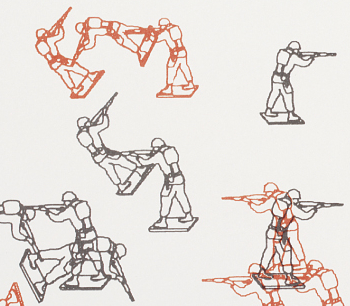

(Illustration – Herbert W. Franke, Squares (Quadrate), screenprint, 1969/70)

Digital Pioneers is a deceptively modest exhibition hidden away in two rooms upstairs at the Victoria and Albert Museum. It contains some of the earliest examples of art produced using electronic devices and computing machinery along with some creative later work.

The bulk of the art in the show was produced between the 1950s and the 1970s. This means that it was produced or recorded as photographs from cathode ray tubes or as print-outs from teletypes and pen plotters. Some of this work will be familiar to students of the history of art computing through reproductions but as with most art reproductions do not tell the whole story.

Seeing the actual work itself is as important for art made using the paraphernalia of early digital computing as it is for art made with linseed oil and cotton duck. What Digital Pioneers drives home is just how deeply and intentionally involved early computer artists were in manipulating the aesthetically limited but socially and ideologically key technology of computing machinery. This leaves both social art historians and code aesthetes with some explaining to do, or at least some catching up.

The show starts in the 1950s with the algorithmic and electronic but non-digital and non-computational photographs of oscilloscope patterns by Ben Laposky and screen-prints of photographs by Herbert W. Franke. Most of the works included in the show are prints of one kind or another, and these are no exception. They record the movement of a beam of light on a cathode ray tube as other prints in the show record the movement of a plotter pen or a laser in a laser printer.

If Constructivism was socially realistic for revolutionary Russia then these works are socially realistic against the backdrop of NATO’s military-industrial-educational complex. They turn the technology of that culture back on itself, using it not to produce weapons or market products but to produce aesthetics. This reclaims a space for perception and contemplation that is not simply militarily or economically exploited. The obsessively quantitative managerial culture of spreadsheets and inventories yields uncomfortably to the qualitative culture of aesthetics, productively so. These strategies continue through the show. Technology is pushed beyond its intended uses to address cultural tasks.

Many of the prints in the show have a similar number of stages of production to Franke’s process of screen, then photograph, then silkscreen prints. His later plotter-drawn work is also screen printed, as are Klee-inspired generative images by Frieder Nake, and Charles Csuri’s random montage of flies. I don’t know what to make of this. It feels like something should have been lost in the move from an original to a print but plotter drawings aren’t particularly originals, being already representations of data structures in the computer’s memory.

Csuri’s lithograph of randomly placed vector outlines of toy soldiers was produced in 1967 during the Vietnam War, a war that ran as long as it did in no small part due to game theory and computer simulation. There are two armies, one plotted in red and one plotted in black. They meet and presumably battle inevitably but only by chance. There’s more of the outside world in art computing than is often assumed.

William Fetter’s wonderful three dimensional vector images of human figures produced for the aircraft manufacturer Boeing, a lithograph from the Cybernetic Serendipity show of 1968, also deal with the human figure within the military-industrial complex. We should not be confused about the status of such images as art by the use and funding of computer graphics by corporations any more than we should be confused about the status of painting as art by the use and funding of oil painting by the Catholic church.

Ken Knowlton’s cheeky nudes and other typographic images of the 1960s and 1980s are an effective escape or release from the constraints of corporate information culture. I’d seen them many times in reproduction but again they are much richer visually as prints.

More detailed systems-based patterns emerge in the 1970s in the work of artists such as Manfred Mohr, Paul Brown, and Vera Molnar. This era that epitomises the approach of rule based serendipity so beloved of later Generative artists. These images are pleasurable to look at but also contain visual or psychological complexity. They also continues to push the performance of computer systems outside of their intended use cases.

By the late 1980s the technical achievements of computerised mass media were exceeding those of art computing. Pen plotters, where they were still used, were no rival to laser printers. Rendered images had to compete with the earliest rumblings of Pixar and Adobe. The increasing availability of digitally designed fashion and entertainment meant that far from being the exception, digital elements in the lived visual environment were becoming the rule.

The reactions to this that art computing in general have made are the subject of the Decode show that is also running at the V&A. Digital Pioneers instead follows the printmaking thread of art computing into the present day where artists such as Roman Verostko, Mark Wilson and Paul Brown have continued with the systems art all-overness of print-based art computing.

To continue in this way marks such work out as something different from the all-pervasive presence of digital imagery in the visual environment. The work has to look different from graphic design and new media rather than from CAD plots or teletype reports, and it does. These works remind us of the history and of the wiring under the board of digital culture. They successfully resist any attempt to reduce them to digital mass media images comparable to the output of the design software that they exist in the same era as.

This switch away from early adoption is necessary to maintain a figure/ground relationship (or a critical distance, or a constructive difference) between the general level of technology in society and the level of technology in art computing. It is not the only solution to this problem, as the Decode show demonstrates, but it is not a retreat.

As a long time fan of Harold Cohen, I found the show’s inclusion of computer generated works from his very earliest 1960s felt-tip-on-teletype-print experiments with generating figure and ground relationships computationally to a recent large-scale full-colour inkjet abstract was a real treat. Plotter drawings of abstract shapes from the 1970s and of human and plant forms from the 1980s show the progress that Cohen made in using computers to rigorously explore how art and images are created and function. Being able to study this work close-up reveals details such as debugging information in the teletype prints and the operation of the collision-detection algorithm in the 1980s images. And it provides the pleasure of seeing detailed, well-composed drawings.

This is a recurring experience in Digital Pioneers. Despite the uniformly dismissive attitude of both popular and academic criticism towards art computing the fact is that when you actually see the work in the flesh it rewards sustained attention. Not as historical or technical curiosities, but as images with cultural and aesthetic content and resonance. To ignore this and to continue to claim that this art is less than the sum of its parts would ironically be to fall prey to a particularly extreme attitude of technological determinism.

The show also contains displays of ephemera including magazines and books such as back issues of the Computer Arts Society’s “PAGE” and William Gibson’s supposedly self-erasing story on a floppy disk “Agrippa”. I’d not seen an actual copy of “Agrippa” before. PAGE back-issues are available online, but their presence here flags an important point.

The revived Computer Arts Society has been key in promoting and deepening understanding of the history of art computing in the UK. The Digital Pioneers show and its excellent accompanying book are a good example of how CAS’s project has spread out into more traditional cultural institutions, and many of the images and exhibits in the show come from the archives that CAS has donated to the V&A.

The “Digital Pioneers” book (by Honor Beddard and Douglas Dodds, V & A Publishing, 2009) serves as a catalogue for the show . It contains an informative introductory essay and printed images of many of the works on display as well as a CD-ROM with 200dpi scans of them. These scans are high-resolution enough to be able to examine the images in some detail, although they are no substitute for seeing the images in the gallery. A slightly excessive copyright licencing notice is the only indication that the book has in fact been produced as one in a series of pattern books from the V&A. It’s a must-have if you enjoy the show or have any interest in early art computing.

Digital Pioneers is an opportunity to really look at the work of early computer artists and to evaluate that work directly rather than through the medium of poor reproductions or through the fog of received critical opinion. As a slice of artistic history that just so happens to have been produced on computer it contains much to reward both the eye and the mind.

Update: Two recently published books provide more extensive background to the period covered by the show, making the history of this fascinating era available to current practitioners –

White Heat, Cold Logic: British Computer Art 1960-1980‘ edited by Charlie Gere et al covers the history of British computer art and the Computer Arts Society.

A Computer in the Art Room by Catherine Mason describes the relationship between British art schools and computing (which is how I became interested in this area in the first place).

The text of this review is licenced under the Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0 Licence.