1 May – 4 August 2019

Featured image: Portrait of Kathy Acker, San Francisco, 1991. Photo: Kathy Brew

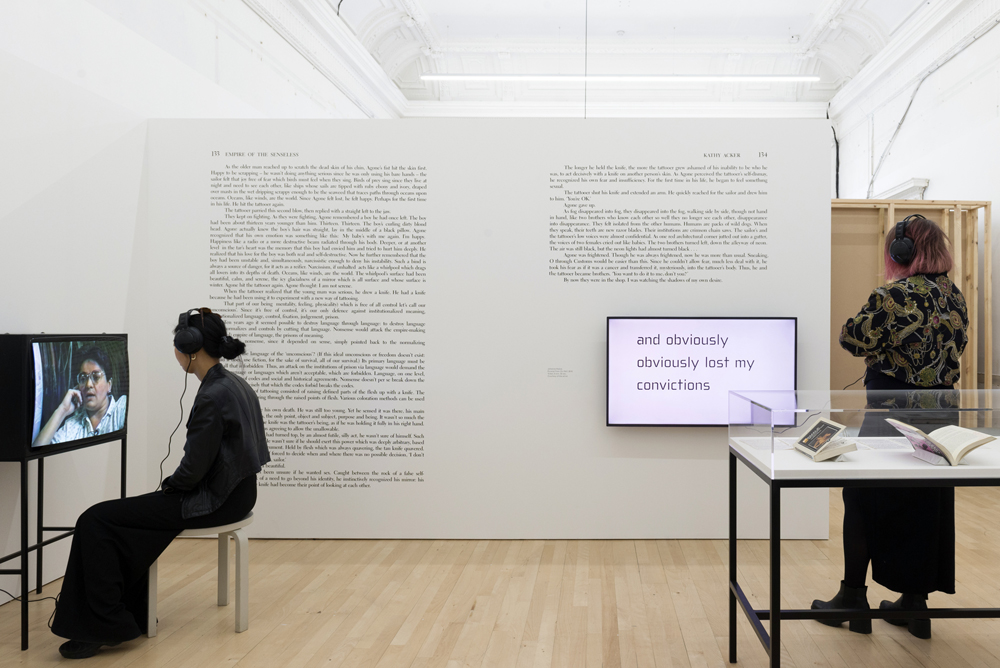

The latest exhibition at the London’s Institute of Contemporary Arts remembers the postmodernist writer Kathy Acker. The many Is in the exhibition title are suggestive of her focus on the exploration of identity and acknowledge the impact she made on the generations of artists following her. Apart from examples of Acker’s practice, such as the documentation of live readings and performances, music and text, this first exhibition dedicated to her in the UK, encompasses works by over 40 artists inspired by her legacy.

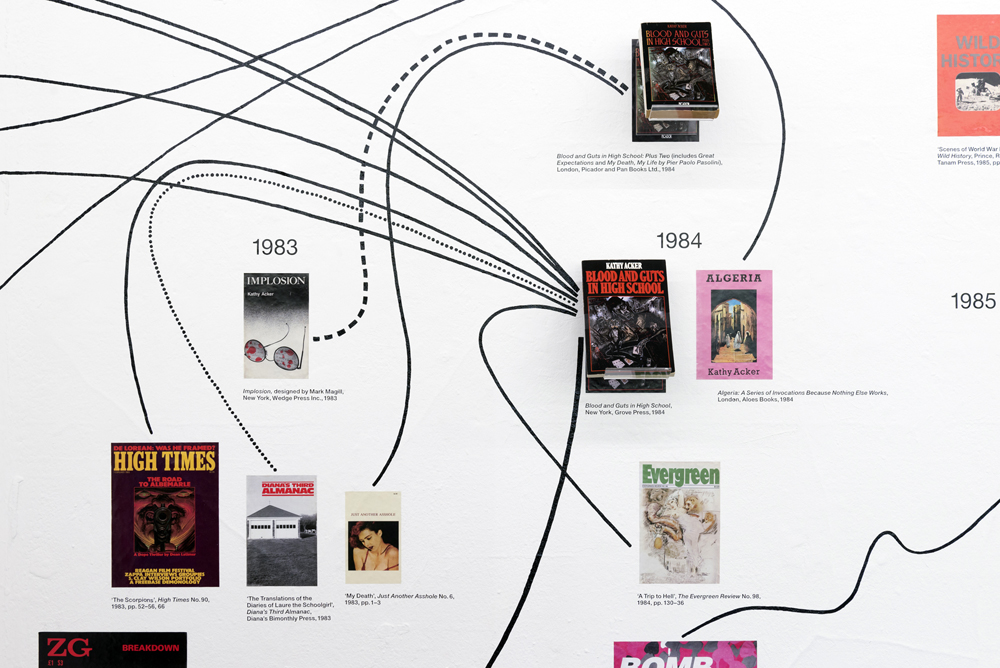

Acker’s relationship with the ICA has begun when she first moved to London, where she lived between 1983 and 1989. At that time, her anti-establishment and anti-patriarchal deconstructive philosophy fit perfectly in time with the atmosphere of the post-punk Tatcher England. She became a significant figure within the cultural landscape and a regular contributor to events at the ICA.

Kathy Acker was a writer who shook the punk art scene in the 70s and 80s New York. She was a lonesome figure in the East Village avant-garde, which at the time was dominated by men. In her prose, Acker often experimented with what being oneself meant. She herself said, “I was splitting the I into false and true I’s and I just wanted to see if this false I was more or less real than the true I, what are the reality levels between false and true and how it works”. Through her practice, she established a performative relationship to one’s identity, a means of exploration into the relationship between sexual desire and violence.

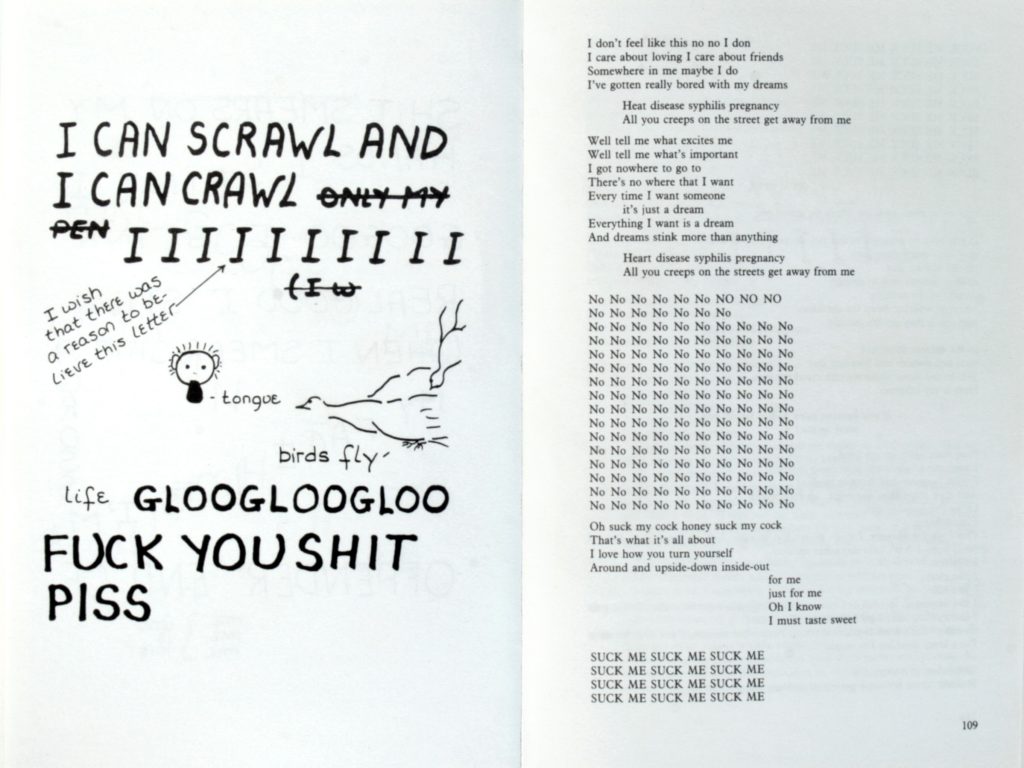

The language was her weapon. She treated it as a means of strong resistance towards patriarchal and heteronormative narratives in the public sphere. Throughout her writings displayed on the walls within the exhibition space, one can see her words from the book Empire of the Senseless (1994), where she declared: “Language, on one level, constitutes a set of codes and social and historical agreements. Nonsense doesn’t per se break down the codes; speaking precisely that which the codes forbid breaks the codes”. The two floors of the ICA are divided into eight sections, each corresponding to one of her books, with appropriate excerpt displayed. Her writing is at the core of the exhibition, on the walls, screens and in glass cases. There is a bit of inconsistency between the ways the literary works are displayed. On the one hand, the exhibition aims at bringing her legacy closer to the public, on the other some of them look hermeneutic when closed off behind a glass, like relics in an ethnographic museum.

However, the other works in the exhibition animate the space and the texts. The binding material between them is the preoccupation with the conflict between personal desires and the domineering narratives in society. Some of the first works to be seen are Jimi DeSana’s Masking Tape (1979) and Refrigerator (1975). The first one depicts a human figure wrapped in masking tape, only genitals exposed and the other shows a woman tied in the refrigerator. These black and white photographs contain suggestive and poetic qualities, also distinctive for Kathy Acker’s work. Further on, Acker’s pictographic “dream maps” which originally existed as large-scale drawings, are juxtaposed with works exploring the female desire in contemporary society, for instance, Reba Maybury’s The Goddess and the Worm (2015), a book telling a story of a dominatrix.

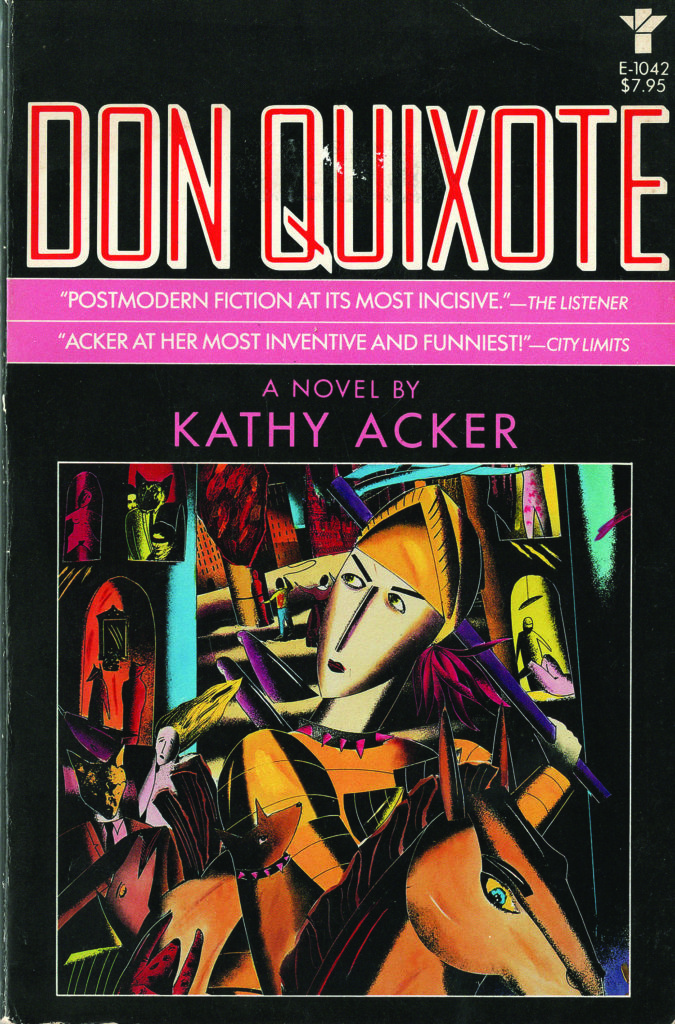

Acker critically assessed the societal norms, declared political relevance of one’s body and focused on marginalised groups. In one of her books presented in the gallery, Don Quixote (1994), the writer transformed the 17th-century canonical protagonist into a female, who becomes a knight by having an abortion and embarks on a journey to address the inequalities of Nixon’s America. Continuing to the second floor, one finds artists addressing the experiences of people who do not confine into the strict gender binary categories and the limitations of our language to describe them. At a back wall of a room, positioned opposite David Wojnarowicz’s works from the Arthur Rimbaud series, are three drawings by Jamie Crewe. Glaire takes Estradiol (2017), Potash takes Spironolactone (2016) and Saltpeter takes Verdigris (2012) show pairs of figures inscribed with the possible side effects of taking steroid hormones, compared with other substances.

The exhibition might leave the viewer in awe and with a head full of ideas. It is an ambitious project, as it addresses the integrative nature of Acker’s practice and evaluates her concepts. It is particularly successful at recognising the writer’s role in the experimental literature scene and the power of her legacy. At times when the society is becoming increasingly politically divisive and the inclusivity comes at a high price for some, it is crucial to remember the pioneers who promoted diversity in the arts. Conceptually speaking, the exhibition structure works well with the aesthetic premise of Acker’s work and creates a dialogue between all the participating artists. However, at times the experience might be overwhelming and becomes an exhibition-goer’s nightmare as it is heavily loaded with text.

I, I, I, I, I, I, I, Kathy Acker finishes with a wall drawing by Linda Stupart, A dead writer exists in words, and language is a type of virus (2019). In it, organic elements, serpents’ eyes and stones are tied to a blueish core resembling a cloud. Around it, there are red tentacles which enliven the virus, which spreads around the wall surface. It is mesmerising, twisted, creating a web of influences. Likewise, it corresponds with the exhibition structure, which is at times challenging to navigate, but ultimately transformative.

Mark Hancock discusses the politics and artistry of Janez Janša’s identity interventions in the context of their recent challenge at the Parliamentary Elections in Slovenia, in June 3rd 2018.

Ideas firmly deduced, tested against all variables and tentatively sent out into the world for appraisal by others, soon betray us as they bend to the whims of anyone they encounter. But that’s the nature of the malleable, post-digital world we live in. Ideas have to adapt and change to suit the warp and weft of the society if they are to survive in some form. How do we lock down our ideas into their final form? And what level of commitment can we expect from our ideas even if we apply intellectual property rights and that centuries-old mark of authenticity, the signature? The art world is particularly vulnerable to the conceit of signed authenticity. A signature often being the only guarantee that you’ll see any return (financial, reputational or otherwise) on your investment. If you really want to play with systems of power and bureaucracy, try altering artist names.

Davide Grassi, Emil Hrvatin and Žiga Kariž all changed their names to Janez Janša in 2007, joining the conservative Slovenian Democratic Party (SDS) at the same time, to explore the bureaucratic and political systems of their home country, Slovenia. The foundation of their actions ever since has been the question: what power exists in a name? And not just the art power system, but what political forces come into play when that name also belongs to the leader of the Slovenian Democratic Party, Janez Janša, (Prime Minister 2004 to 2008 and then again in 2012 to 2013). Incidentally, or perhaps not, Janez Janša, the politician was born Ivan Janša. The renaming of the three artists becomes a sort of double bluff when you also start to ask who the ‘real’ Janez Janša is.

It would be easy to assume that the work of Janez Janša is simply another playful, flaccid baiting of the art world and right-wing political hegemonies. All too often work that challenges the political system might as well be challenging the rules of the Italian Football League, for all the difference in the world it makes beyond the enclosed loop of the art community. There’s only so far that insulting the work of Damien Hirst with another work of art can get you. But the Janez Janša artists have chosen to pierce through the membrane of the art world and make a social difference.

In the Slovenian Parliamentary Elections on the 3rd June 2018, one of them ran as a member of the opposition party, Levica (The Left) in Grosuplje the home district of the ex-Prime Minister, Janez Janša. In a press release, Janez Janša (the artist) said: “Running for parliament is a logical consequence of the view I have towards society. I care about what is happening. I react to things. I want to change them. (…) Society must be organized in such a way that the state begins to serve its citizens, as opposed to serving capital. Capital has no interest either for society or for art or for the individual.”

There is something inherently political in multiple authors using a single name, at least if you cast an eye over recent history. Reference points include Wu Ming, the Italian author collective that produced a number of literary works (they published a best-selling novel, Q, in 1999). They evolved from the Luther Blissett collective, whose playful, socially engaged activities defy the concept of the singular creative voice. This concept seems so alien to much of the mainstream media, particularly in Wu Ming’s home country of Italy, where they have been accused of everything from cybercrime to the less savoury aspects of rave culture. It’s this uncertainty about ownership that seems to bring a nervous lump to the throat of media and political gatekeepers. Perhaps this revolves around two questions so central to capitalism: If you’re doing nothing wrong, why hide behind a nom de plume or a collective? And, who do I send the check to, if I want to buy an Art?

On top of this, copyright issues become complex when the roster of names increases as well. Because we still want ideas to be owned, even when they are expanded through homages and pastiches. Copyright, as the attorney representing the Janez Janšas points out, is a legal construct, protecting, “original artistic (and scientific) creations, which are expressed in any way. A work is protected by copyright only if it was created by a human being (an author) and bears a stamp of author’s personality.” With work by Luther Blissett and Wu Ming, at least the authors can be understood as ‘artists’, even anonymously. Janez Janša, Janez Janša and, last but not least, Janez Janša have layered this authorship of their artwork with another layer of copyright/ownership complexity.

They refer to this work as collateral art, a phrase resonant with the phrase collateral damage, used to describe the acceptable casualties of battles. Collateral art is the acceptable damage on their ideas and projects from engagement with companies and institutions: ID cards, membership cards, the whole panoply of detritus that comes with the work. The artists want this collateral art, often customised by companies on request, to question the relationship between artworks and functional objects, “exploring post-Fordist means of production.” Any art historians still trying to shoehorn the belief of the gifted singular genius crafting his (note the gender pronoun: now discuss) solo masterpiece, probably hasn’t been paying close enough attention. The individual work of art often only becomes such with the signature of the artist attached as providence. When the work of art carries the signature of a non-artist though, can it still be brought into the art world as a valid comment on… anything? Paperwork sent to institutions by Janez Janša, and signed by an official becomes art. But whose art?

The answer, of course, is that it is their art. Whatever bureaucratic grindstone the works have been milled under, they ultimately belong back with the artists. It is they who return the work back to the art world through the exhibition. The exhibition co-produced by Moderna galerija (MG+MSUM) and Aksioma – Institute for Contemporary Art, Ljubljana, and curated by independent curator Domenico Quaranta, in 2017, was a chance to display and reflect back on ten years of work by the artists. Called the Janez Janša® exhibition, on display were works including Signatures (2007 – ongoing) which explored interventions of the Janez Janša name into public spaces, such as the Hollywood Walk of Fame (Signature, 2007), or Signature (Copacabana), in Rio de Janeiro, 2008. Playfully appearing in numerous locations around the world. Or Mount Triglav on Mount Triglav, an action performed in August 2007. This action commemorated “the 80th anniversary of the death of Jakob Aljaž; the 33rd anniversary of the Footpath from Vrhnika to Mount Triglav; the 5th anniversary of the Footpath from the Wörthersee Lake across Mount Triglav to the Bohinj Lake; the 25th anniversary of the publication of Nova Revija magazine and the 20th anniversary of the 57th issue of Nova Revija, the premiere publication of the SLOVENIAN SPRING; this was a re-enactment of Gora Triglav (Mount Triglav), by the OHO group in 1968 and the latest in a chain of re-enactments, as it was also performed by in 2004 by the Irwin Group.

The conference in the same year, Proper and Improper Names: Identity in the Information Society conference, hosted by Aksioma – Institute for Contemporary Art, Ljubljana, and curated by Marco Deseriis in 2017, invited speakers including Natalie Bookchin, Marco Deseriis, Kristin Sue Lucas, Gerald Raunig, Ryan Trecartin, Wu Ming. The subjects under discussion arose from Marco Deseriis’ book Improper Names: Collective Pseudonyms from the Luddites to Anonymous. Deseriis, as keynote speaker, talked about the genealogy of the improper name. This is Deseriis’s term for the use of pseudonyms by artist collectives, including Wu Ming (who presented a talk at the conference) and Ned Ludd, the fictional leader of the English Luddites.

Releasing your ideas out in the wild doesn’t always guarantee they will come back to you unscathed or even return at all. The works of the Janez Janša collective are sent out to corporate systems, being adapted and altered, and returned. Or at the very least offering a challenge to accepted forms of ideological structures. In the Slovenian elections on 3rd June, the Slovenian Democratic Party (SDS) won with 25% of the votes. Levica won 9.0%. The SDS is a far-right, anti-immigration party, reflecting the increasing rise of right-wing parties across Europe right now. The leader of the SDS, Janez Janša, now has the opportunity to form a right-wing government. If this happens, and by the time you read this, it may well have, it would continue the shift in European Councils members towards the right.

There’s nothing new in declaring that everything is in flux. That’s the nature of our hyper-accelerated world. But right now there is a creeping sense that The Other is also to be viewed as The Enemy. The social, political value of art has to change to mean something in what is little short of a battle for a better society for ourselves and others across the globe if it is to have any value whatsoever. Janez Janša, Janez Janša and Janez Janša’s work reflect this evolution by being part of the society around them. Being part of the electoral system reflected this challenge and desire to be part of the real world and to make art mean something more than gallery space and conference papers. If art wants to survive and continue to belong to everyone, then it needs to be part of the world we are living in right now. No one work of art ever changed the world, but it helps us unravel and see through the propaganda of systems. We all need to become Janez Janša®.

The final outcome of the recent Slovenian Elections remains uncertain as Social Democratic Party’s Janez Janša attempts to form a coalition government.

More images at Flickr – https://bit.ly/2yniHYL

More about Janez Janša – http://www.janezjansa.si/about-jj/

This essay is a response to Identity Trouble (on the blockchain), the second in the DAOWO lab series for blockchain and the arts. Rosamond reflects on both ongoing attempts to reliably verify identity, and continuing counter-efforts to evade such verifications.

Online transactions take place in a strange space: one that blurs the distinctions between the immediate and the remote, the intimate and the abstract. Credit card numbers, passing from fingers to keyboards to Amazon payment pages, manage complex relations between personal identity and financial capital that have been shifting for centuries. Flirtations on online dating platforms – loosely tied to embodied selves with a pic or two and a profile – constitute zones of indistinction between the intimate spheres of the super-personal, and hyper-distributed transnational circuits of surveillance-capital. Twitter-bot invectives mix with human tweets, swapping styles – while all the while bot-sniffing Twitter bots try to distinguish the “real” from the “fake” voices[1]. Questions of verification – Who is speaking? Who transacts? – proliferate in such spaces, take on a new shape and a shifted urgency.

How does personal identity interface with the complex and ever-changing technical infrastructures of verification? How is it possible to capture the texture of “identity trouble” in online contexts today? The second in the DAOWO event series, “Identity Trouble (on the blockchain),” addressed these questions, bringing together a range of artists, developers and theorists to address the problems and potentials of identification, using technical apparatuses ranging from blockchain, to online metrics, to ID cards and legal name changes. The day included reflections on both ongoing attempts to reliably verify identity, and continuing counter-efforts to evade such verifications.

Before going into the day in any detail (and at the risk of going over some already well-trodden ground), I want to try to piece together something which might – however partially – address the deeper histories of the problems we discussed. Of course, identity was an elusive concept long before the internet; and the philosophical search to understand it has run parallel to a slow evolution in the technical and semiotic procedures involved in its verification. In fact, seen from one angle, the period from the late nineteenth century to present can be understood as one in which an increasing drive to identify subjects (using photo ID cards, fingerprints, signatures, credit scores, passwords, and, now, algorithmic/psychometric analysis based on remote analysis of IP address activity) has been coupled with a deep questioning of the very concept of identity itself.

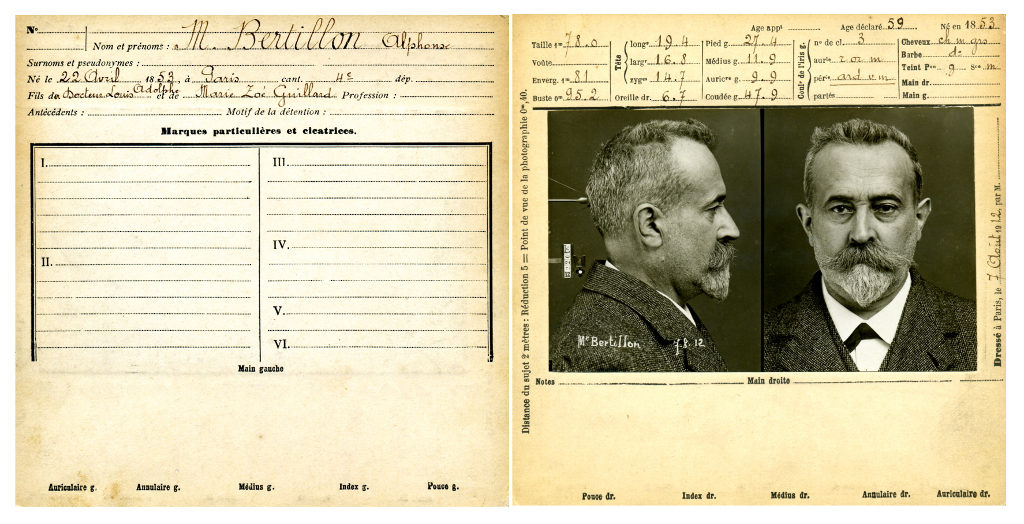

On the one hand, as John Tagg describes, in the second half of the nineteenth century, the restructuring of the nation-state and its disciplinary institutions (“police, prisons, asylums, hospitals, departments of public health, schools and even the modern factory system itself”[2]), depended on creating new procedures for identifying people. This involved, among other things, yoking photography to the evidentiary needs of the state – for instance, through Alphonse Bertillon’s anthropometric identity card system, invented in 1879 and adopted by French police in the 1880s. The identity cards, filed by police, included suspects’ photographs and measurements, and helped them spot repeat offenders.

This impulse to identify, it seems, has only expanded in recent times, given the proliferation of biometric and psychometric techniques designed to pin down persons. On the biometric end of this spectrum, retinal scans, biometric residence permits and gait recognition technologies manage people’s varying levels of freedom of movement, based on relatively immutable bodily identifiers (the retina; the photographic likeness; the fingerprint; the minute particularities of the gait). On the psychometric end of the spectrum, private companies calculate highly speculative characteristics in their customers by analysing their habits – such as “pain points.” The American casino chain Harrah’s, for instance, pioneered in analysing data from loyalty cards in real time, to calculate the hypothetical amount of losses a particular gambler would need to incur in order to leave the casino. The pain point – a hypothetical amount of losses calculated by the company, which may be unknown to the customer herself – then provided the basis for Harrah’s’ real-time micro-management of customer emotion, enabling them to send “luck ambassadors” out onto the floor in real time to boost the spirits of those who had a bad day [3].

On the one hand, then, identification apparatuses have become ever more pervasively intertwined with the practices of daily life in industrialized societies since the latter half of the nineteenth century; this produced new forms of inclusion and exclusion of “exceptional” subjects within various institutional regimes. On the other hand, just as the technical and semiotic procedures associated with verifying identity were proliferating and becoming ever harder to evade, modern and postmodern thinkers were deeply questioning what, exactly, could possibly be identified by such procedures – and why identity had become such a prominent limiting condition in disciplinary societies. James Joyce’s character Stephen Dedalus marvels at the lack of cellular consistency in the body over a lifetime. While an identifying trait, such as a mole on the right breast, persists, the cells of which it is made regenerate repeatedly. (“Five months. Molecules all change. I am other I now.” [4]) How, then, can debts and deeds persist, if the identificatory traits to which they are indexed are intangibly inscribed in an ever-changing substrate of cellular material?

In the mid-twentieth century, Foucault and Barthes deeply questioned the limitations identity imposed on reading and interpretation. Why, for instance, need authorship play such a prominent role in limiting the possible interpretations of a text? “What difference does it make who is speaking?” [5]

In ’nineties identity discourse, theories of difference became particularly pronounced. Cultural theorists such as Stuart Hall radically questioned essentialist notions of cultural identity, while nonetheless acknowledging the political and discursive efficacy of how identities come to be narrated and understood. Hall and others advocated for a critical understanding of identity that emphasized “not ‘who we are’ or ‘where we came from’, so much as what we might become, how we have been represented and how that bears on how we might represent ourselves. Identities are… constituted within, not outside representation.” [6]

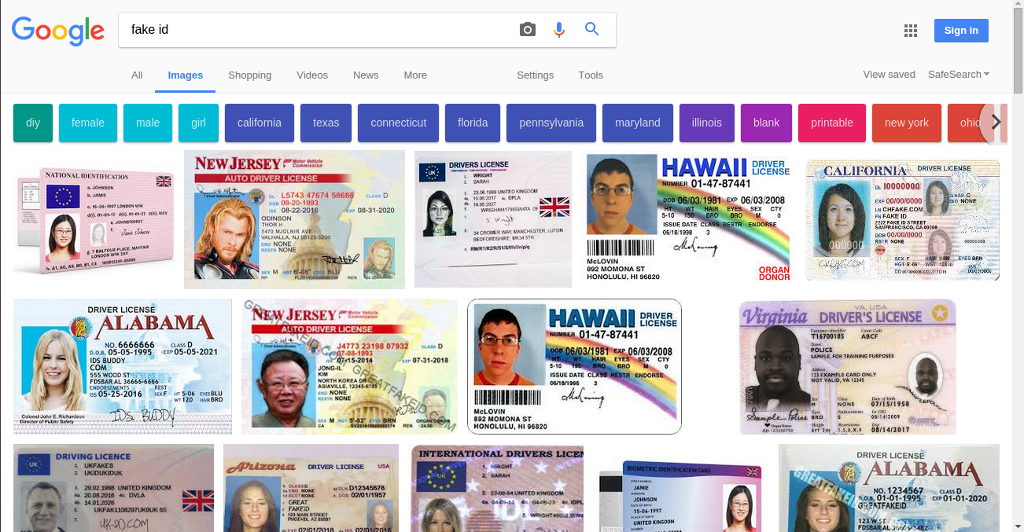

On the one hand – so I have said – myriad technical apparatuses have aimed to ever more reliably capture and verify identity. On the other hand, myriad critical texts have questioned identity’s essentialist underpinnings. But today, these lines have become blurred. The anti-identitarian mood permeates technical landscapes, too – not just theoretical ones. Fake IDs, identity theft, and other obfuscations have grown ever more complex alongside apparatuses for identification; indeed, such fakeries have both emerged in response to, and driven yet further developments in technologies for identity verification as is the case in a Fully-Verified system. The frontiers of identification are ever-changing; each attempt to improve technologies for verifying identity, it seems, eventually provokes the invention of new techniques for evading those verifications.

At the inherently uncertain point of contact between person and online platform, new forms of anti-identifications are practiced – invented or adapted from previous stories. In one bizarre example from 2008, a Craigslist advert posted in Monroe, Washington requested 15-20 men for a bit of well-paid maintenance work. The men were to turn up at 11:15 am in front of the Bank of America, wearing dark blue shirts, a yellow vest, safety goggles and surgical masks. As it turned out, there was no work to be had; instead, the men had been summoned to acts as decoys for a robbery – a squid-ink trail of similarity to help the thief escape. The idea, though inventive, wasn’t entirely original; it was described by police as a possible copycat of the plot in the film The Thomas Crown Affair (1999) [7.

Today, the anti-identitarian mood has spread far beyond small-scale manoeuvers like this. Multiple large-scale data breaches – such as the recent Equifax breach, which compromised the data of over 145 million customers [8] – have put a cloud over the veracity of millions of people’s online identities. The anti-identitarian mood becomes broad, pervasive, and generalized in data-rich, security-compromised environments. It becomes a kind of weather – a storm of mistrust that gathers and subsides on the level of infrastructures and populations.

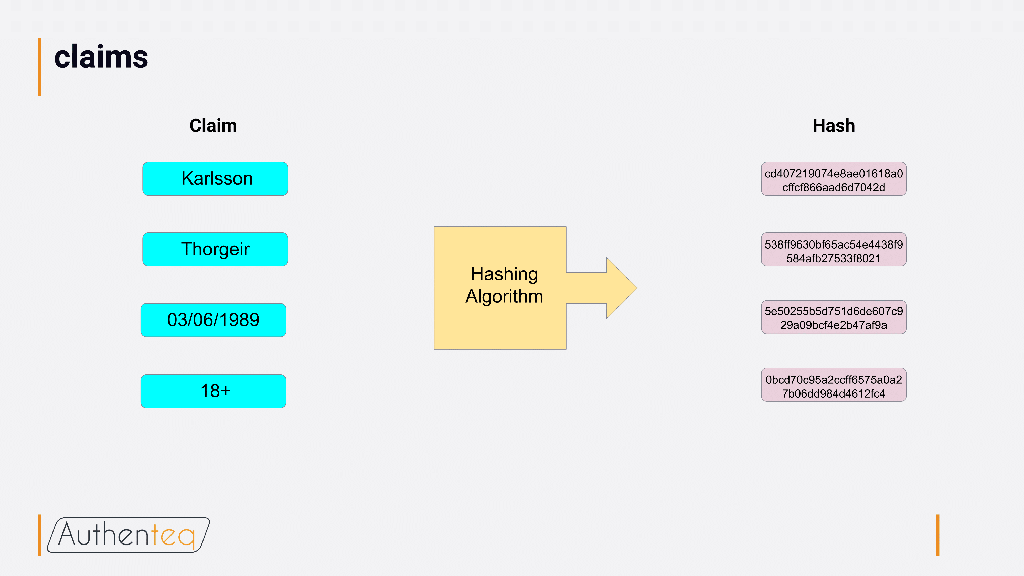

Such are some of the complexities that the DAOWO speakers had to contend with. At the Goethe Institute, we thought through some of the ways in which identities are being newly constituted within representation – ways that might, indeed, answer to the technical and philosophical problems associated with identification. Backend developer Thor Karlsson led us through his company Authenteq’s quest to provide more reliable online identity verification. Citing the ease with which online credit card transactions can be hacked, and with which fake accounts proliferate, Karlsson described Authenteq’s improved ID verification process – a digital biometric passport, using blockchain as its technical basis. Users upload a selfie, which is then analysed to ensure that it is a live image – not a photograph of a photograph, for instance. They also upload their passport. Authenteq record their verification, and return proof of identity to users, on the BigChainDB blockchain.

A hashing algorithm ensures that users can be reliably identified, without a company having to store any personal information about them. Authenteq aims to support both identity claim verifications and KYC (Know Your Customer) implementations, allowing sites to get the information they need about their users (for instance, that they are over 18 for adults-only sites) without collecting or storing any other information about them. Given how much the spate of recent large-scale data breaches has brought the storage of personal data into question, Authenteq’s use of blockchain to circumvent the need to store personal data promises a more secure route to verification without revealing too much of personal identity.

Nonetheless, while Karlsson and Authenteq were optimistic that they can make meaningful improvements in online identification processes, other provocations focused on the potential problems associated with such attempts at identification – on the protological level, on the level of valuation, and on the level of behaviour-as-protocol. Ramon Amaro delivered an insightful critique of blockchain and the problem of protological control. There is no such thing as raw data – inputs are always inflected by social processes. Further, the blockchain protocol relies heavily on consensus (with more focus on consensus than on what, exactly, is being agreed upon) – which reflects a need to protect assets (including identity) and oust enemies that is, ultimately, a capitalist one. Given this, how can identity manoeuver within the blockchain protocol, without always already being part of a system that is based on producing inclusions and exclusions – drawing lines between those who can and cannot participate?

My own contribution focused on systemic uncertainty in the spheres of personal valuation, looking at online reputation. In a world in which online rankings and ratings pervade, it seems that there is a positivist drive to quantify online users’ reputations. Yet such apparent certainty can have unexpected effects, producing overall systemic volatility. At the forefront of what I call “reputation warfare,” strategists such as Steve Bannon invent new ways to see systemic reputational volatility as a source of value itself, producing options for the politicians they represent to capitalize on the reputational violence produced on sites like 4chan and 8chan.

While these contributions reflected on some of the critical problems associated with pinning down identity’s value, some of the artists’ contributions for the day focused on the ludic aspects of identity play. Ed Fornieles’ contribution focused on the importance of role play as a practice of assuming alternate identities. In his work, this involves thinking of identity as systemic, not individual – and considering how it might be hacked. In many of Fornieles’ works, this involves focusing attention on the relation between identity and the platforms on which they are played out. Behaviour becomes a kind of protocol; role play becomes a reflection on strands of behaviour as protocol.

We ended the day with a screening and discussion of My Name is Janez Janša (2012), a film by three artists who, in 2007, collectively changed their names to Janez Janša, to match that of the current president of Slovenia. The film, an extended meditation on the erosion of the proper name as an identifier, catalogued many instances of ambiguity in proper names – from the unintended (an area of Venice in which huge numbers of families share the same last name) to the intentional (Vaginal Davis on the power of changing names). It also charted reactions to the three artists’ act of changing their name to Janez Janša. What seemed to confound people was not so much that their names had been changed, but rather that the intention of the act remained unclear. In the midst of today’s moods of identification, there are high stakes – and many clear motives – for either obscuring or attempting to pinpoint identity. Given this, the lack of clear motive for identity play seems significant; by not signifying, it holds open a space to rethink the limits of today’s moods of identification.

The DAOWO programme is devised by Ruth Catlow and Ben Vickers in collaboration with the Goethe-Institut London, and the State Machines programme. Its title is inspired by a paper written by artist, hacker and writer Rhea Myers called DAOWO – Decentralised Autonomous Organisation With Others

14.00-17.30 – Workshop devised and hosted by Ruth Catlow and Ben Vickerswith Ramon Amaro, Ed Fornieles Thor Karlsson & Emily Rosamond

19.00-20.30 – Screening of the documentary My Name is Janez Janša (2012) Introduced by Ruth Catlow and Janez Janša

Identity Trouble (on the blockchain) is the second event in the DAOWO blockchain laboratory and debate series for reinventing the arts.

Identity is considered one of the hardest problems in the blockchain space, as it is here that it really matters how human and machinic systems connect. With the potential to fix and potentially impinge upon the relationship between our subjective sense of self, freedom to use multiple identities and our machine-assigned identities.

These difficulties span personal, social, technical and political domains. From a global perspective, blockchains have begun to be put forward as the most efficient and secure solution for providing identification to refugees and with it, access to basic social infrastructure such as healthcare, voting, financial and legal rights and services. As steps towards both national identity and global identity systems are being accelerated, perhaps most notably in Goal 16 of the UN 20 Global Goals, as being; “By 2030, provide legal identity for all, including birth registration”.

These drives sit in tension with fears about the increasing convergence of political and commercial control through identity technologies, tensions between: name and nym; person and persona; privacy, transparency and security; and the interests of the private individual and public citizen. All of which run counter to the proclamation that “Having two identities for yourself is an example of a lack of integrity”.

At the first DAOWO workshop we discovered more about current developments for blockchain application within the arts. At this event we seek to further challenge and reconsider the identity question in the context of the arts-blockchain ecosystem.

This workshop will be opened with a keynote by developer Thor Karlsson who will present Authenteq, an automatic identity verification platform and discuss his company’s approach to design for “trust and transparency in communications and transactions between users”.

This will be followed by a series of provocations by theorists and arts practitioners on cultural identity jamming, dangerous bias in the datasets that inform machine learning, and decentralised reputation management.

Laying foundations for the workshop in which we will work together to develop new stories about a set of characters living in the arts. How they operate and feel differently as the impact of blockchain technologies takes effect on their personal and professional role within the artworld.

Join us to describe what will go wrong? And what might just work?

“The system of reference of names started to crack … This made me reflect on issues such as identity vs identification, multiplicity vs multiplication, the name as an interface between the private and the public, and the personal name as a brand.” – Janez Janša, Director of My name is Janez Janša

Following the second workshop of the DAOWO series we present this film about names, identity and pseudonymity in a long history of academic, artistic and popular identity play for political and personal reasons. In 2007 three artists changed their names to that of Janez Janša, the then Prime Minister of Slovenia, whilst remaining ambiguous about their reasons. This documentary film reflects on the subjective and public meaning and utility of a person’s name and documents the interpretations and responses provoked by journalists, the general public and the “original” Janez Janša.

The Janez Janša® exhibition is on display at Museum of Contemporary Art Metelkova, Ljubljana

18 October 2017 — 08 February 2018

Ramon Amaro

Ramon Amaro is a Lecturer in Visual Cultures at Goldsmiths, University of London; Research Fellow in Digital Culture at Het Nieuwe Instituut in Rotterdam; and visiting tutor at the Royal Academy of Art, The Hague. Ramon has worked as a former Assistant Editor for Big Data & Society (SAGE), quality design engineer for General Motors, and programmes manager for the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME). His research interests include philosophy, machine learning, and black study.

Ed Fornieles

Ed Fornieles is an artist whose works are responsive to the movement of information. Fornieles uses film, social media platforms, sculpture, installation and performance to express the interaction of family, relationships, popular memes, language and the subcultures of 21st century experience. His work operates within the logic of immersive simulations, which construct and enact alternative political and social spaces. His projects often involve cultural, social, and infrastructural production, making interventions that reconfigure the viewer’s position and sense of self.

Thor Karlsson

Thor Karlsson is the lead backend developer at Authenteq, a privacy tool and identity verification platform for online services. With over six years of professional experience in .NET and Java, Thor works in backend systems with an emphasis on clean code, testability and optimization. Thor is currently focused on implementing core backend systems used for the Authenteq ID verification and face recognition platform.

Emily Rosamond

Emily Rosamond is a Canadian artist, writer and educator. She completed her PhD in 2016, as a Commonwealth Scholar in Art at Goldsmiths, University of London. She is Lecturer in Visual Cultures at Goldsmiths, and Joint Programme Leader on the BA Fine Art & History of Art. She exhibits individually and with the collective School of The Event Horizon.

The DAOWO programme is devised by Ruth Catlow (Furtherfield) and Ben Vickers (Serpentine Galleries & unMonastery) in collaboration with the Goethe-Institut London, and the State Machines programme.

This project has been funded with the support from the European Commission. This communication reflects the views only of the author, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein.

“It is highly unlikely that we, who can know, determine, and define the natural essences of all things surrounding us, which we are not, should ever be able to do the same for ourselves – this would be like jumping over our own shadows.” – Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition

One & Other, part of the Zabludowicz Collection’s annual Testing Ground Project, is a curatorial collaboration between MA Curating students from Chelsea College of Arts and CASS, London Metropolitan University. The show holds together works by Ed Atkins, David Blandy, Cécile B. Evans, Leo Gabin, Isa Genzken, Rashid Johnson, Tim Noble, Sue Webster, Ferhat Ozgur, Jon Rafman, Ugo Rondinone, Amalia Ulman, Ulla Von Brandenburg and Gillian Wearing.

The exhibition threads the simultaneously disturbing yet beautiful dualities between the simulated daily persona humans perform and, as Atkins’ work states, ‘actual’ human presence – the distinction between real and the Other.

Walking into the main area of the late 19th century former Methodist Chapel, Atkins’ work echoes through the two-storey building in an authoritative manner, “read my teeth, read my lips, listen, listen, you don’t know how to listen”.

Situated on the ground floor of the space, No one is more WORK than me (2014) appears to be a lower grade CGI avatar of Dave, a persona from Atkins’ Ribbons. I will just call him Dave. Dave is glitchy, at times not synced. His desire to bring himself into the perceived physicality is overwhelming as he elaborates on causal harm features making himself more human, ‘it’s blood, it’s blood, there’s a bruise’. All the works within the space, share the same space and thus are always accompanied by the backdrop of Atkins’ voice, repetitively stating ‘this is my actual head’ and describing the features on the figure’s face. Dave’s comments about his ‘actual’ body features shape the ambience and undertones of the show.

Shown on a flat screen placed on the floor, Dave commands the space to his will as the only video work not bearing headphones. Dave sings for us on multiple occasions, specifically performing Bryan Adam’s ‘Everything I Do (I Do It for You)’. At times he becomes almost irrationally frustrated with himself and the audience, tells us to do him ‘a favour’ and ‘fuck off’. His performance – and frustration – are immersive and quite literally frame the entire show around the work’s presence. Cécile B. Evans’ work positioned directly opposite it, corresponds with teeth, although harmoniously to the corporeal visuals provided by Atkins’ work.

Evans, now exhibiting at the Tate Liverpool, has been making outstanding work since I first came across Hyperlinks, or it didn’t happen (2014) at Seventeen Gallery in London. In One & Other, her video, The Brightness (2013), involves the visual three-dimensional participation of the audience as the invigilators provide 3D-glasses. She states ‘I am here because I am plastic’ and ‘I was real then’, whilst a CGI render of pirouetting teeth is shown, dislocated from their place of origin, the mouth.

The teeth, traditionally a sign interpreted from dreams as a symbol of anxiety, are animated, dancing and may be symbolising the unease experienced when becoming something outside of what you are. Evans’ work is placed within close proximity to Atkins’ work, adjusting for a very comfortable relational approach to both pieces in conversation with each other as motifs of personifying the unanimated, the plastic.

Sleeping Mask (2004) is a mask of a human face made out of painted wax. Playing with notions of human disguised as human, Wearing creates a re-enactment of one of the most human physical properties, the face. Sleeping Mask was placed on a plinth, on a slightly elevated podium, with a singular spotlight shining on it like the Genie Lamp in the Cave of Wonders, thus proving that particular notion to be very effective.

Less effective, and regrettably so, one of the weaker curatorial links to the show, was the inclusion of Amalia Ulman’s Excellences & Perfections – Do You Follow? (2014). As a scripted online-performance viable and lived through her Instagram account, Ulman appears to be critiquing the vanity of self-indulgent approval on social media. Through creating the persona of an overactive digital self, Ulman’s work comes as no surprise when taking into consideration the wider context of the conceptualisation of One & Other. Having been featured in The Telegraph this time last year, she seems to have grabbed the attention of a more public young audience, themselves feverishly present on social media. Whilst her inclusion is not controversial at all, it more so had the teetering effect of ‘oh, it’s that work by Amalia Ulman’. The decision to include her in the show might be interpreted as making a statement – audience participation within this critique becomes redundant as it is vocalised through the very tool she is critiquing. Nonetheless, the surprising addition of Sue Webster and Tim Noble’s work, Ghastly Arrangements (2002), made up for the aforementioned curatorial paradox.

Placed in a room of their own, the work captivates all attention in the darkness. Ghastly Arrangements is an arrangement of silk and plastic flowers in a ceramic vase with a single spotlight projecting its shadow onto the wall. The work addresses the concept of human duality without using humans as a visual medium, perhaps even addressing it more appropriately because it doesn’t involve humans- it involves shadows. The Other in One & Other, is an entity by which can be projected onto, containing duality. Such is Ghastly Arrangements, as the Other assumes a signifier through the shadow as the self. An object can thus be a more powerful vehicle for thought than representation itself – another point made with Jon Rafman’s choice regarding plinths.

A friend of mine once said that a good plinth signifies art with value, making it the ultimate art object. Rafman’s New Age Demanded (2014) is a series of digital sculptures, scattered on tall mirror coated plinths with self-assured confidence on the wooden stage stairs in the upstairs area. Faceless representations of humans are created through quite uncanny looking textured materiality; smooth marble, dripping resin, copper patina and rough concrete. The non-faces are unidentifiable and the absence of definite characteristics moulds an audience-subjective projection of the Other self. The mirror plinth adds to the dimension of projecting oneself, the performative experience and known duality of the self in contemporary society begging the question of, ‘How many people do we exist as?’

Overall, within such an overwhelmingly impressive structure housing the Zabludowicz Collection, a near-perfect group show can prove very challenging to execute. The architecture of the space, its high ceilings, stage and upper balcony, may interfere with the presentation of the art. In One & Other’s case, it felt as though there was too much going on, conceptually but more importantly spatially. Rafman’s immense installation would have been better suited as an isolated entity in the balcony upstairs, whilst the works of Atkins, Evans, Wearing, Webster and Noble could have also stood their own ground conceptually without any further additions. One & Other felt like it could have done with constraining itself to only one type of self-identifying duality, instead of attempting to assess multiple, and although I love the work of Rashid Johnson, it felt slightly out of place within the space; perhaps less is more.

Whilst this piece of writing is only comprised of personal highlights and observations, One & Other is a show not to be missed, and to inspire fellow young and aspiring curators.In the curatorial team for One & Other were Caterina Avataneo, Ryan Blakeley, Nadine Cordial Settele, Sofía Corrales Akerman, Gaia Giacomelli and Angela Pippo.

On until the 26th of February 2017.

All images by Tim Bowditch, courtesy of the Zabludovicz Collection.

Choose Your Muse is a new series of interviews where Marc Garrett asks emerging and established artists, curators, techies, hacktivists, activists and theorists; practising across the fields of art, technology and social change, how and what has inspired them, personally, artistically and culturally.

Gannis is informed by art history, technology, theory, cinema, video games, and speculative fiction, expressing her ideas through many mediums, including digital painting, animation, 3D printing, drawing, video projection, interactive installation, performance, and net art. However, Gannis’s core fascinations, with the nature(s) and politics of identity, were established during her childhood in North Carolina. She draws inspiration from her Appalachian grandparents singing dark mountain ballads about human frailty, her future-minded father working in computing, and a politicized Southern Belle of a mother wearing elaborate costumes, performing her prismatic female identity.

“I am fascinated by contemporary modes of digital communication, the power (and sometimes the perversity) of popular iconography, and the situation of identity in the blurring contexts of technological virtuality and biological reality. Humor and absurdity are important elements in building my nonlinear narratives, and layers upon layers of history are embedded in even my most future focused works.” Gannis.

We begin…1. Could you tell us who has inspired you the most in your work and why?

The complete list of people who have inspired me is inordinately long. I’m sharing with you here clusters of some of the “most most” inspiring.

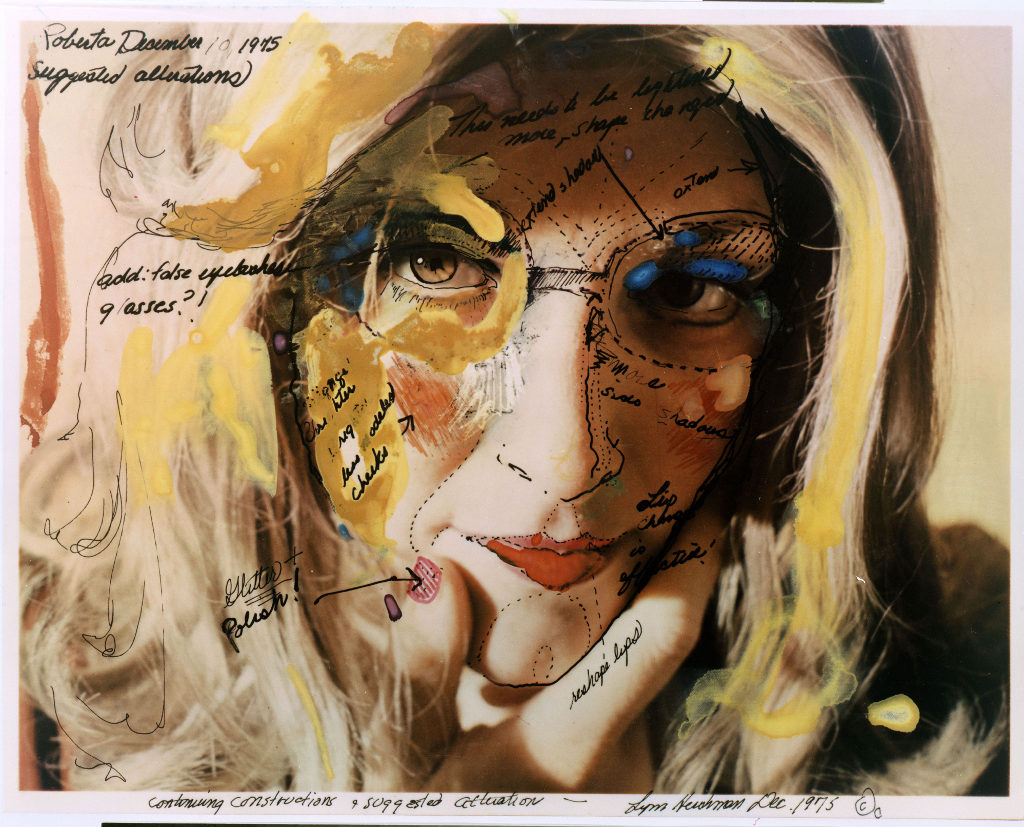

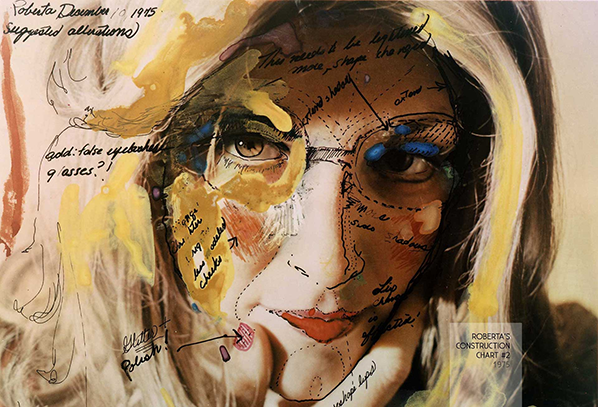

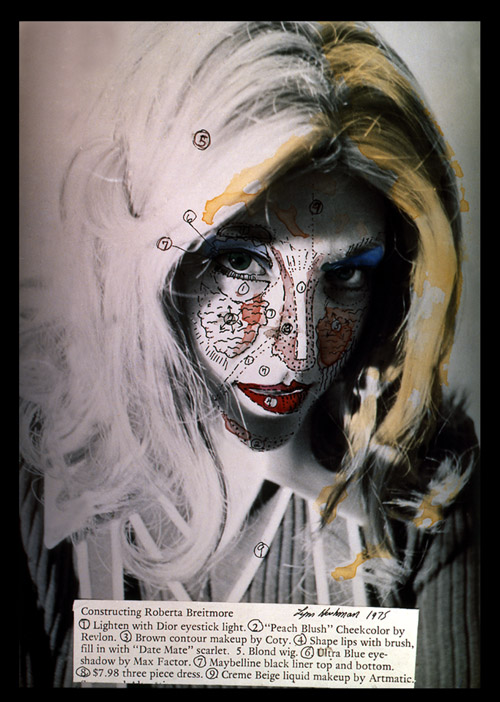

Lynn Hershman Leeson, Maya Deren, Lady Ada Lovelace, Mary Wollstencraft – I saw Lynn Hershman Leeson’s Conceiving Ada in the late 90s. It was my first introduction to her work, and

I have been blown away by her prescience ever since. Deren, Lovelace, and Wollstencraft, like Leeson, have all been groundbreaking in their creative, scientific and intellectual contributions to humankind.

Yael Kanarek, Marge Piercy, Octavia Butler, Sadie Plant, Jonathan Lethem, Harry Crews and Flannery O’Connor – Artist Yael Kanarek’s “World of Awe” was one of the first net art pieces, through its poetry and world building, to inspire me to transition from painting into a new media arts practice. Piercy and Butler are two favorite authors, and they have both written novels where women travel into the past and to the future to reconcile their identities, to come to terms with their present selves — themes that constantly recur throughout my work. Plant opened up broad vistas to me as a woman and feminist working with technology, and the melange of genres Lethem mashes up in his fictional works: sci fi, noir, autobiography, and fantasy, appeals to my own hybrid sensibilities. Crews and O’Connor testify to the absurdity of the human condition, and being a native of the “American South,” their gothic sensibilities resonate with me deeply.

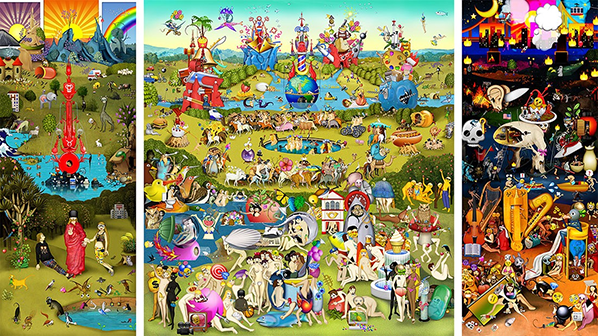

Philip Guston, Suzanne Valadon, Artemisia Gentileschi, Louise Bourgeois, Hieronymus Bosch and Giotto di Bondone – I studied painting at a school where Guston had taught (many years before I arrived there), and coincidentally we share the same birthday. I have always felt a very strong connection to his work, particularly to his late work, where he resisted the art establishment and made pictures that he felt truly represented his time. Valadon, an autodidact, likewise bucked the conventions of 19th century “lady painting” focusing on the female nude throughout her oeuvre. Gentilsechi in the 17th Century established herself as an artist who painted historical and mythological paintings, rendering women with more agency and strength than her male contemporaries. Bourgeois’s work, the rawness of her drawings particularly, were quite significant to me as a young artist. Twice I got to attend her Sunday Salons in New York, sharing my work with her. She was a tough critic by the way. Bosch and Giotto have long been favorites, the enigmatic quality of Bosch’s vision, and the amalgam of Medieval and Renaissance perspectives colliding in Giotto’s paintings.

Charlie White, Laurie Simmons, Gregory Crewdson, Renee Cox & Cindy Sherman – I think of these photographers as important conceptual forerunners of a Post-Photography movement that seems to be reaching its apogee now. They were each essential to me as I searched for a new aesthetic language, after throwing away my oil paints and canvases.

And today there are so many younger artists who I have deep respect for, Gretta Louw, Angela Washko, RAFiA Santana, Jeremy Bailey, Lorna Mills, Andrea Crespo, Clement Valla, Faith Holland, Jacolby Satterwhite, Morehshin Allahyari and Alfredo Salazar-Caro (to name only a few). They all have significant presences online, and I encourage readers to “google them” for glimpses into the contemporary visions that are shaping and predicting our future.”

2. How have they influenced your own practice and could you share with us some examples?

In my teens and 20s I copied much of the work of my sheroes and heroes. There is little I can share with you of that work now, as I’d copy then delete back then. To be more accurate, since it was physical work, I’d copy and destroy. I destroyed more work than I saved until I found a way to absorb and remix through the filter of my own identity.

Today I identify as a visual storyteller who cuts and pastes from the threads of googleable art history, speculative fiction and networked communication in efforts to aggregate some kind of meaningful narrative. Appropriation feels like an authentic artistic response to mediated culture, registering at a different conceptual frequency than simple mimicry. I mean making a painting like Giotto or Bosch doesn’t make sense in the 21st century, well, unless you “emojify” it (wink). Here is one recent work where my quotation is obvious, “The Garden of Emoji Delights.” In the other works below, a collection of influences are embedded, but perhaps less perceptible on first glance.

3. How is your work different from your influences and what are the reasons for this?

It is essential that my work be different semiotically from the historical influences I mentioned above, if I am to actually understand the nature and power of their work — how each of them were incredibly perceptive and responsive to “their time.” They produced authentic images or texts (or code) that were assembled from aspects of their cultural milieu. Their expressions were comprehensible to their contemporaries, even if at times only a few of their peers engaged. Communication is key to every human enterprise. Nonetheless the infinite (and often futureminded) perspectives of these historical figures still reverberate in our contemporary collective consciousness and influence us to “perceive differently” in our own time.

To be different from influences who are of my own time also involves comprehending why they have an impact on me. They avoid any kind of creative and intellectual status quo. Being unique seems improbable in the internet age, but there are still innumerable ways that we can creatively parse our relationships to the past, present and future, both in concert and contrast to one another.

4. Is there something you’d like to change in the art world, or in fields of art, technology and social change; if so, what would it be?

There are many art worlds. In the more mainstream, celebrity-dominated, auctioneer enabled art world, whose market I rarely follow, but when I do, I find it to be bloated by One Percenters consumed by commodities trading, I would advocate for, if I had the power to do so, more economic temperance, less aura fetishization, and yeah, VR headsets that provide clothes for hackneyed metaphors.

It’s demoralizing that I cannot foresee, at least in the short term, a world without radical income inequality. Our world continues to be populated by a majority of “have nots” who are dominated by a tiny dominion of “haves.” It seems in every financial, social, educational, and entertainment sector, including the visual arts, capital obstructs as much as it supports creativity. Still I believe that the “other art worlds” can and will affect, actually currently are affecting change (incremental as it may seem), through social advocacy programs that embrace and foster diversity; through economic and technological models that celebrity the ubiquity instead of the scarcity of contemporary digital art; through independent artists who define their success in terms of cultural, instead of, or in addition to market value.

Positive changes are happening. Compare our cultural landscape to even two decades ago, and we see a much more diverse population represented in the arts. A new generation of artists and technologists are hopeful about their capacity to shape a better future, while being mindful of what’s a stake if they do not.

That said, and to finally answer your question directly, I’d like to see a change — a major turn in the tides of fascism, racism, xenophobia, and misogyny that are flooding countries around the world — so that the various art worlds, the ones that frustrate me, and the ones that inspire me, can survive.

5. Describe a real-life situation that inspired you and then describe a current idea or art work that has inspired you?

Sitting with and drawing digital portraits of my 99 year old Grandma Pansy Mae in January of 2015 inspired me to begin “The Selfie Drawings” project. Being in the presence of someone who has witnessed so much radical social and cultural change, over the course of almost a century, motivated me to interpret, and then stage a series of reinterpretations of myself/selves, within the context of a post-digital age. Pansy Mae was a woman born before women had the right to vote in the United States, a woman with only an 8th grade education who raised my mother, and myself to never let our gender or our class (personally) deter us from pursuing our ambitions. Grandma is now 101 years old, and I wished her Happy Birthday in binary code this past December 31st.

“Nasty Woman” is a current meme that has really struck a chord with me. I have worn a “Nasty Woman” necklace everyday, since November 7th, (the day I picked it up from the studio of artist Yael Kanarek). Embracing the nomenclature that was meant to denigrate a woman has instead empowered and galvanized a collective of women as they face, and resist, the alarming possibilities of increased subjugation under Trump’s leadership.

I recently participated in the NASTY WOMEN exhibition in New York city, (which raised over $42,000 for Planned Parenthood), because I am such a woman, a nasty woman, a bitch, a Jezebel — a complex and empathetic human being who believes change and equality can only occur when we speak up, when we eschew “politeness” in the face of serious threats to our autonomy and personhood.

6. What’s the best piece of advice you can give to anyone thinking of starting up in the fields of art, technology and social change?

I’ve got a few bits of advice. First, as an artist, work; as a technologist, feel; and as an advocate for social change, empathize. Then toss up your FEW cards (feel, empathize and work) and apply them to other aspects of your life as well.

Secondly I suggest losing, if you possess, the sense of what you think you’re entitled to because you are more special and deserving than others. This doesn’t mean you deny the gifts you possess. Nor does it mean you eschew your ambitions or balk at your successes. Brand yourself, or your cause, by all means, if that informs your practice or generates support for your work. But the “I’m a genius, so I have the right to be licentious, egotistical and completely selfserving at the sacrifice of others” trope may (temporarily) get a man into the White House, but generally is tiresome, if not loathsome, to progressive art professionals.

7. Finally, could you recommend any reading materials or exhibitions past or present that you think would be great for the readers to view, and if so why?

What I’ve been reading lately: Object Oriented Feminism edited by Katherine Behar; Artemisia Gentileschi, The Language of Painting by Jesse Locker; Lynn Hershman Leeson Civic Radar edited by Peter Weibel; Hope in the Dark | Untold Histories, Wild Possibilities by Rebecca Solnit; The Year of the Flood by Margaret Atwood

I recommend these books as a resistance to sophomoric twitter threads usurping all of your attention.

Pipilloti Rist : Pixel Forest New Museum, http://www.newmuseum.org/exhibitions/view/pipilotti-rist-pixel-fores

It is okay for art to wash over you, so that you can revel, even relax, in its beauty…for a while.

____________________________________________________________________

Monster of the Machine : Laboral

curated by Marc Garrett http://www.laboralcentrodearte.org/en/exposiciones/monsters-of-the-machine

A timely and provocative exhibition (thrilled to have work included).

__________________________________________________________________

Dreamlands: Immersive Cinema and Art 1905-2016

http://whitney.org/Exhibitions/Dreamlands

A landmark show for moving image works!

__________________________________________________________________

Women’s March On Washington (Saturday, January 21st!) https://www.womensmarch.com/

…or one of the other 386 protests taking place on the same day around the world!

https://www.womensmarch.com/sisters

#notmypresident

Choose Your Muse Interview: Jeremy Bailey | By Marc Garrett – 26/06/2015

http://furtherfield.org/features/interviews/choose-your-muse-interview-jeremy-bailey

Choose Your Muse Interview: Annie Abrahams | By Marc Garrett – 10/09/2015

http://www.furtherfield.org/features/interviews/choose-your-muse-interview-annie-abrahams

Choose Your Muse Interview: Lynn Hershman Leeson | By Marc Garrett – 13/07/2015

http://www.furtherfield.org/features/interviews/choose-your-muse-interview-lynn-hershman-leeson

Choose Your Muse Interview: Stanza | By Marc Garrett – 03/11/2015

http://www.furtherfield.org/features/interviews/choose-your-muse-interview-stanza

Choose Your Muse Interview: Igor Štromajer | By Marc Garrett – 09/06/2015 http://www.furtherfield.org/features/interviews/choose-your-muse-interview-igor-%C5%A1tromajer

Choose Your Muse Interview: Mike Stubbs, Director of Fact in Liverpool, UK | By Marc Garrett – 20/05/2015

http://www.furtherfield.org/features/interviews/choose-your-muse-interview-mike-stubbs-director-fact

With Virginia Barratt, Francesca da Rimini, Cory Doctorow, Shu Lea Cheang, Jennifer Lyn Morone™ Inc, Andrew McKenzie, Angela Oguntala, Dr. Richard Stallman, Stelarc, Jacob Wamberg, Lu Yang

Inspired by the Phillip K Dick short story “The Electric Ant” this year’s CLICK seminar curated with Furtherfield explores how identity and perceptions of reality have changed in a world where humans, society and technology have merged in unexpected ways. Who are we, what’s real, where can we expect to go from here, and how can we get there together?

From future shock to FOMO (fear of missing out), accelerating technological change has disrupted our perception of ourselves and the world around us. Pervasive computing, genetic engineering, artificial intelligence, drones and robotics, neural interfaces and implants, 3D printing, nanotechnology, big data and ever more technologies are redrawing the boundaries of what it means to be human and what it means to be you.

At the same time the design and unintended consequences of technology are creating new mass behaviours. And the productive forces of social media, peer production, hacker culture and maker culture are creating new possibilities for creation and expression. All of this changes how we relate to one another within society as part of the public.

This years CLICK festival, co-curated by Furtherfield sets out to explore questions related to identity and perceptions of reality in a world where humans and technology have merged in unexpected ways.

Virginia Barratt. VNS Matrix founder, cyberfeminist, Virginia Barratt is a PhD candidate at the University of Western Sydney in experimental poetics. Her doctoral topic is panic, engaging tensions between ontological meltdown/psychic deterritorialisation and ontological security. Panic is remediated from its pathological narrative and reimagined as a space of urgency/agency from which to act. Her work of performative text, SLICE, is forthcoming from Stein and Wilde.

Francesca da Rimini explores the poetic and political possibilities of internet-enabled communication, collaborative experimentation and (tel)embodied experiences through projects such as her award-winning dollspace. As cyberfeminist VNS Matrix member she inserted slimy interfaces into Big Daddy Mainframe’s databanks, perturbing the (gendered) techno status quo. Her doctoral thesis at the University of Technology Sydney investigated cultural activism projects seeding radical imaginations in Jamaica, Hong Kong and the UK. A co-authored book, Disorder and the Disinformation Society: The Social Dynamics of Information, Networks and Software, will be out in May 2015.

Cory Doctorow is assigned the label Internet philosopher, who writes, blogs and debates about online rights. Doctorow is convinced that copyright is an out-dated idea that damages the Internet and criminalizes peoples’ online actions improperly. According to Doctorow the current regulations of copyrights are obsolete by the unstoppable copy machine we call the Internet, which continues to produce samples of available online material such as pictures, music and text. Cory Doctorow is also an award-winning science fiction author and co-editor at boingboing.net.

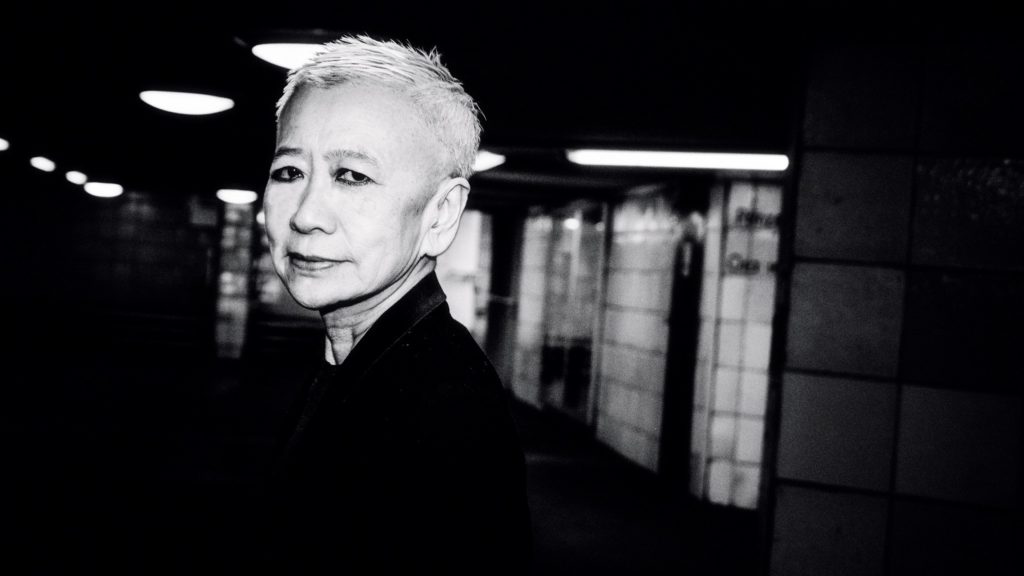

Shu Lea Cheang is known for her pioneering work in the field of media art and she is a true multidisciplinary and activist artist whose work spans from film to net art and performance (online, and in galleries) and video installation. Beginning the 1981 she was involved in the media activist’ collective ‘Paper Tiger TV’. Among her important multimedia works is the ‘Brandon Project’ (1998-99). Guggenheim Museum’s first official engagement with the then-emerging medium of internet art and one of the first works of this medium commissioned by a major institution. Following the production of the cyber porn film ‘I.K.U.’ (2000)(first porn film to be shown at the Sundance Festival) she focused on questions of copyrights and economy in media culture. Shu Lea Cheang holds a BA in history from the National Taiwan University, and a MA in film studies from New York University.

Jennifer Lyn Morone™ Inc (US). In a world before the Internet – information, transmission and dissemination was a controlled and regulated endeavour. The advent of the information superhighway, which is currently littered with social media sites run by billion dollar corporations, has blurred the lines of community ownership of one’s personal information and the individual. By incorporating herself she effectively wrestled the control of her digital self, back from corporations and took an active role in the sale of her information. Morone has been motivated by an underlying fascination with the relationship between technology, human beings, and the socio-economic political implications the melding of the two produce. That social concern, spurned Jennifer to create Jennifer Lyn Morone™ Inc.

Andrew McKenzie (UK). The British Andrew McKenzie is the core of The Hafler Trio. His professional career began more than 3 decades ago and through the years he has worked with different professions such as audio designer, psychotherapist, hypnotherapist and workshop leader in Creative Thinking. McKenzie is also co-founder of Simply Superior where he teach creative processes that challenge the way you think in order to make you realize what you know, and are aware of not knowing. McKenzie’s projects and present goals all involve applying everything learned by experience over the last 48 years for the benefit of other. Andrew McKenzie defines himself as a mood engineer, specializing in changing people’s lives.

Angela Oguntala (US/DK) is a designer whose work sits at the intersection of technology, design, and futures studies. Currently, she heads up an innovation lab for Danish designer Eskild Hansen, envisioning and developing future focused products and scenarios. In 2014, she was chosen by a panel consisting of the United Nations ICT agency, Ars Electronica, and Hakuhodo (Japan) as one of the Future Innovators for the Future Innovators Summit at Ars Electronica – called on to give talks, exhibit her work, and collaborate on the theme ‘what it takes to change the future’.

Dr. Richard Stallman launched the free software movement in 1983 and started the development of the GNU operating system (see www.gnu.org) in 1984. GNU is free software: everyone has the freedom to copy it and redistribute it, with or without changes. The GNU/Linux system, basically the GNU operating system with Linux added, is used on tens of millions of computers today. Stallman has received the ACM Grace Hopper Award, a MacArthur Foundation fellowship, the Electronic Frontier Foundation’s Pioneer Award, and the Takeda Award for Social/Economic Betterment, as well a several doctorates honoris causa, and has been inducted into the Internet Hall of Fame in 2013.

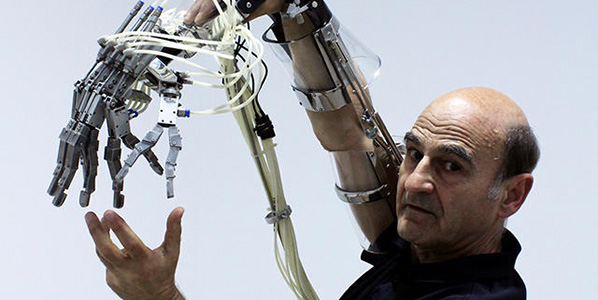

Stelarc (AU). An extra ear. A third arm. Six legs. A walking head. The Australian performance artist Stelarc is questioning and challenging whether or not it is possible to optimize the abilities of the human body. Stelarc has since the 1960s not hesitated to include advanced technology in his projects. After having examined several test on his own body, he announce a manifest claiming that the human body is out-dated and no longer meets the information society we live in. Stelarc uses his artwork to convey how the human body hypothetically will appear in the nearest future, if the technology is considered an extra dimension to the evolution.

Jacob Wamberg, Professor of Art History at Aarhus University. Principal Investigator for Posthuman Aesthetics. In the posthuman field, he has co-edited The Posthuman Condition: Ethics, Aesthetics and Politics of Biotechnological Challenges (2010) with Mads Rosendahl Thomsen et al., and is now working on tracing the early contours of the posthuman paradigm (ca. 1900-1930), focusing on Dada, Futurism and Functionalism.

Shanghai based artist Lu Yang utilize a range of mediums known from pop culture such as Japanese manga and anime, online gaming, and sci-fi. She mixes these with discourses of neuroscience, biology, and religion, when she asks what it means to be human in the 21st century. Her depictions of the body, death, disease, neurological constructs, sexuality/asexuality, gender is unsentimental, confrontational and in their morbid humor not for the squeamish. Lu Yang is one of the most influential Chinese contemporary artists rising at the moment. She is a graduate from the China Academy of Art New Media. Her work has the last couple of years been internationally shown at museums and galleries and she has in 2014 been residency at AACC in New York and Symbiotica in Australia.

Please visit the CLICK website to purchase your ticket.

Ticket: 350 DKK. / Student: 250 DKK.

Featured image: Lynn Hershman Leeson Portrait (Photo Credit: Ethan Kaplan)

Woman, Art & Technology is a new series of interviews on Furtherfield. Over the next year Rachel Beth Egenhoefer will interview artists, designers, theorists, curators, and others; to explore different perspectives on the current voice of woman working in art and technology. I am honored to begin this series with an interview with Lynn Hershman Leeson, a true pioneer in the field who has recently produced !Women Art Revolution- A Secret History.

Over the last three decades, artist and filmmaker Lynn Hershman Leeson has been internationally acclaimed for her pioneering use of new technologies and her investigations of issues that are now recognized as key to the working of our society: identity in a time of consumerism, privacy in a era of surveillance, interfacing of humans and machines, and the relationship between real and virtual worlds. She has been honored by numerous prestigious awards including the 2010-2011 d.velop digital art and 2009 SIGGRAPH Lifetime Achievement Awards. Hershman also recently received the 2009 John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellowship, an award which supported her latest documentary film !Women Art Revolution – A Secret History.

Rachel Beth Egenhoefer: Your most recent project is the film “!Women Art Revolution” which you have been collecting materials for and working on for the past forty years. Why is now the time to present it as a finished work?

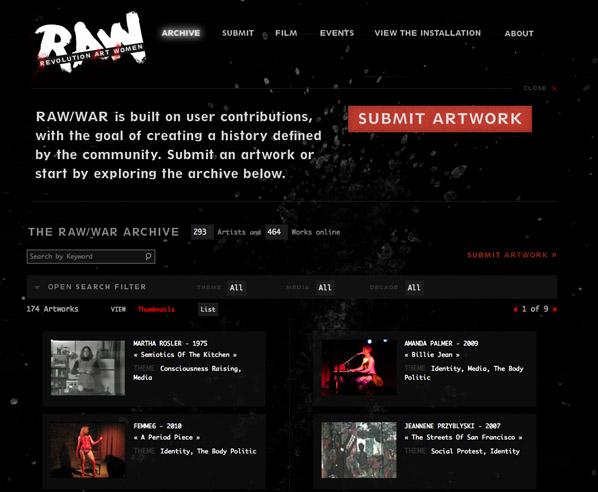

Lynn Hershman Leeson: TECHNOLOGY! The film is one narrative, but I’ve put the entire 12,428 minutes online through Stanford University Library, making all the narratives and aterials accessible, so in effect there are no out takes. Also the RAWWAR org archive/website allows people to continue the story online. So the story continues to grow beyond the single narrative, which technology allows us to do now.

Additionally, I wanted to push out into public view the graphic novel, curriculum guide, and the story to affect the legacy while women who created the movement could be appreciated.

RBE: Can you expand on how you see the RAWWAR story continuing online? Or maybe what is the goal of the archive/website? Do you envision people adding to it?

LHL: Yes, it was made specifically so that people, especially younger generations will be able to add information. At the Walker Art Center, they have scanning stations and are training people how to upload work onto the site. My hope is that people from around the world will add materials and it will be a living repository of this type of growing and accessible information.

RBE: The film has been touring in the U.S., what has the response been?

LHL: Incredible. It has been in over 60 cities, and standing ovations in San Francisco, Houston, Toronto, Sundance, Berlin and Mexico City. People seem deeply affected by this secret history and seem to appreciate knowing about it.

RBE: Has the response varied either with geography or current events?

LHL: Not really, it seems vibrantly appreciated worldwide despite it being about women in America.

RBE: Can you explain the grammar behind the title “!Women Art Revolution”?

LHL: If you mean why the ! first, it was so we would be listed first, rather than under W. It didn’t work, but that was why we did it originally. It also is a wild exclamation at the start, which is what the movement was.

RBE: The film is described as presenting the relationships between the Feminist Art Movement and the anti-war and civil rights movements, showing how historical events sparked feminist actions. Do you see any connections to be made with the current Occupy Movements?

LHL: Yes, absolutely. In some ways because it is about how the disempowered and invisible people were able to gain their place in culture; how people who had their voices silenced were able to amplify their message and subverted social systems, with work that expressed censorship, freedom of expression, social justice and civil rights and directly made political change. It is an inspiring story of reinvention.

The goals were clearer than with Occupy. But the disenfranchised edges of culture is similar.

RBE: A lot of your early works dealt with issues of identity. How do you think the notion of identity has changed over the years?

LHL: It has become more technological, more global, more cyborgian. We now, because of the internet are linked globally and that has resulted in a “hive mind” and in turn, that seems to be a cohesion and holding together the individual fracturing that had occurred over the last two decades

RBE: Can you expand on the idea of the “hive mind that seems to be holding together the individual fracturing”? What makes up the hive, what is fracturing us? Is this good or bad or neither?

LHL: The hive is social media and people who participate in the Internet grammar. There is a congealing through access to information. As individuals, I think we have been fracturing, rupturing, split for decades and have become multi faceted and multi taskers. But there’s a price in the lack of personal cohesion that results. I think that having a common reference or ‘hive’ is a very good thing, as it tests our idea of ‘reality’, and serves as a hub of communication.

RBE: Do we make our own hives? Or are those defined for us (either by others/ FaceBook/surveillance/ etc)?

LHL: We are all part of global re-patterning that is happening live on a global scale and it is naive to assume we can act independently or not be connected or affected. We are constantly challenged, influenced by peripheral and pervasive information and in turn we have become fodder for surveillance and digital integration.

RBE: Some contemporary artists and thinkers have been critical of our online selves and physical selves. Sherry Turkel for instance has described people as “performing themselves” online by constantly updating Facebook profiles, tweets, etc to show an ideal version of ourselves. Can you draw any distinctions between virtual, physical, and performative selves?

LHL: I think we perform ourselves every day, not only on social media, but in all interactions. I do not think all images or versions of ourselves are ideal. There is absolutely a difference between real/physical and virtual selves. They each have a context, reference and function. As far as being performative, that depends upon the distinction used for how it is used. One can, in fact, consider life itself and everything one does as performance.

RBE: This interview is going to be part of a series of interviews with women working in Art & Technology. What do you consider to be important today about being a woman working in art & technology?

LHL: Ada Lovelace wrote the first computer language, Mary Shelley envisioned artificial intelligence, Hedy Lamar invented spread spectrum technology, which led to cell phones. Women have been enormously prescient in visioning and affecting the future of the world through technological linkage systems.

RBE: Do you think it is still useful to discuss the female voice as a separate voice in the field?

LHL: I think the female voice is critical in all aspects of the future and should not be limited to a category.

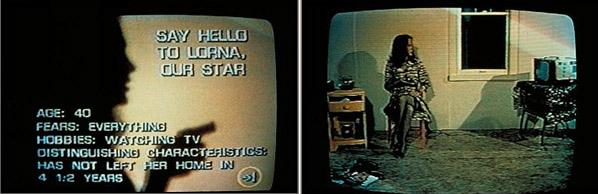

RBE: One of your earlier works, LORNA, depicts a woman who never leaves her apartment and becomes more and more fearful as she watches ads and news on the TV. Some might say television media has gotten far worse since the 80s in both fear mongering and controlling conversations. What do you think about the current state of the media?

LHL: Right, the idea of media as totally affecting our outlook has shifted. Media is no longer omniscient! The 99% are activating their voices and warbling into existence. There are other problems with social media… deeper ones that splay into the cracks of fractured identities and insist on more disruption and lack of focus. But perhaps that is what is affecting our constantly changing evolution.

RBE: If LORNA were around today what would she be thinking or doing in her little 1 room apartment?

LHL: Blogging and all forms of social media including excessive and obsessive shopping, no doubt. She would probably not really be agorophobic either. She would, however, probably be paranoid. She would use a webcam and notice all the ones surrounding her no matter where she moved.

RBE: Do you have hope for change in the future?

LHL: Hope? It is inevitable. I believe in the next generation! They always, in their amnesiac optimism re invent the future in ways that can’t be predicted.

RBE: You have been involved in academia for some time, what do you think is important to be teaching in the Universities right now?

LHL: Independent thinking and creativity, the maintenance of ethics and a profound sense of humor!

RBE: Do you have any new projects you are working on?

LHL: Yes, at least 3 .A new film which is part 3 of my trilogy about the evolution of the human specis, a new installation that uses scanned beating heart cells, and a long term project about Tina Modotti.

Find our more on Lynn Hershman Leeson and Woman Art Revolution here: http://www.lynnhershman.com/http://womenartrevolution.com/