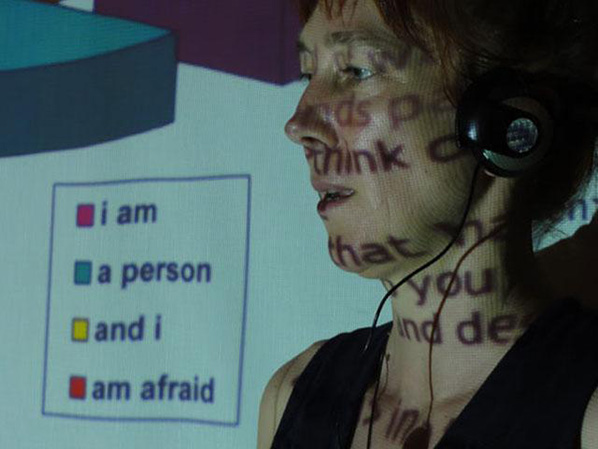

Featured image: Helen Varley Jamieson performing “make-shift,” Brisbane, 2012; photo by Suzon Fuks

“Overlapping and fluid spaces… spaces emerging between physical realities and the ethereal digital / electric space: a third space grafted from the real-time confluence of the stage + remote locations.” – Helen Varley Jamieson

Cyberformance artist Helen Varley Jamieson is creating a new Internet performance work, “we r now[here]”* for the Art of the Networked Practice | Online Symposium (March 31 – April 2). The title and description of the work poetically articulate her thinking on networked space (third space) as a medium for online theatrical experimentation: “‘we r now[here]’ is about nowhere and somewhere: the ‘nowhere’ of the Internet becomes ‘now’ and ‘here’ through our virtual presence.” (* Special thanks to Annie Abrahams who provided the title for the work: “we r now[here],” and to Curt Cloninger who inspired it.)

To set the “stage” for this new work, we discuss Helen’s pioneering achievements in the genre she has coined as cyberformance: the combination of cybernetics and cyberspace with performance. Helen has created a rich body of online theater work dating back to 1999, when dial-up modems were still the operable connection, long before Skype and Google Hangout became popular Web-conferencing tools. As one of the founders of UpStage, an open source platform for online theatrical presentation, Helen is a leading catalyst, researcher, director, and maker who for years has been reimagining the Internet as a global space for theater and performance.

****

Randall Packer: You coined the term cyberformance in the early 2000s after discovering the potential of the Internet as a medium for live performance. What were your first steps in rethinking live theater for ethereal, networked “third space?”

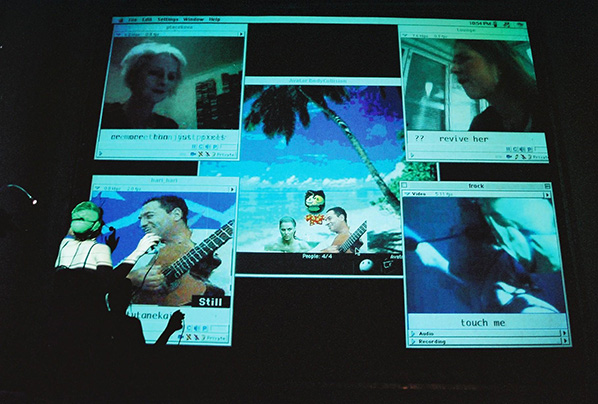

Helen Varley Jamieson: When I first started working with Desktop Theatre and experienced the intense liveness of our interactions despite being physically separated by thousands of miles, I understood that it was possible to feel a quite visceral sense of presence and real-time connection via the internet. We were improvising and performing in The Palace, a graphic-sonic chat application, and our audiences were mostly other “Palatians” – who weren’t always particularly interested in what we were doing. I began to think about how we could bring this work to a theatre audience, people who wanted to see a performance. The first time I tried this was at Odin Teatret in Denmark at a Magdalena Project festival, with a short performance that aimed to demonstrate the possibilities of cyberformance. Adriene Jenik and Lisa Brenneis from Desktop Theatre were performing with me from California, in The Palace which was projected onto a screen. I was using someone’s mobile phone for the internet connection as this was 2001 and there wasn’t internet throughout the building at that time. Afterwards, a heated debate erupted amongst the audience (who were theatre practitioners) about whether or not this could be called theatre. This experience challenged me to question whether or not cyberformance was “theatre” (which of course required first answering the question, what is “theatre”?): how is technology changing our definitions of “theatre”? and what place does cyberformance have within theatre?

RP: You define cyberformance as “utilizing Internet technologies to bring remote performers together in real-time for remote and or proximal audiences.” How does the distributed nature of cyberformance differ from live, traditional theater that situates actors and audience in a single, physical location?

HVJ: Obviously there are many interactions that are not possible, and the entire context is different: instead of sitting together in a darkened auditorium, hearing the rustles and breathing of your fellow audience members and smelling whatever smells, you are (usually but not always) alone in front of a computer. There are time and seasonal differences, as well as cultural and linguistic, for individual audience members. There might be a knock at the door or a phone call or other outside events that intrude on someone’s experience while online. So there is much more variety in how the performance is received than there is in a proximal situation. To give one example, during the 101010 UpStage Festival, one performer and some audience were located at a museum in Belgrade; it was the same day as the gay pride march there, which was disrupted by rioting anti-pride protestors, and the museum staff had to lock the doors to keep everyone safe – cars were burning in the street outside. Inside the locked museum, the performer kept going and the festival continued with the riot raging outside, and those of us online were getting updates about the situation from those in the museum.

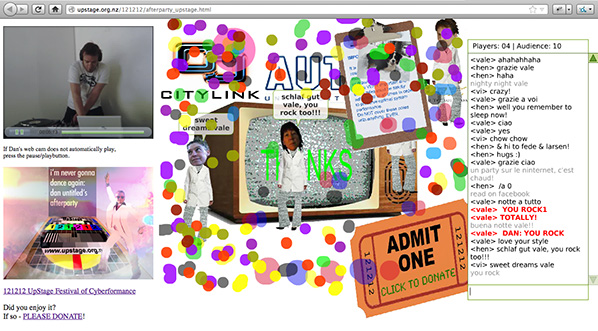

There is also a different kind of relationship between audience and performers, at least in performances using platforms such as UpStage, where the audience have the possibility to chat with each other and with the artists. There is a level of familiarity and equality, as opposed to the separation of the 4th wall in traditional theatre. Different codes of behaviour apply – for instance it can happen that the online audience might start chatting about something unrelated to the performance, which then becomes a part of the performance; people seated in a theatre auditorium wouldn’t normally strike up a general conversation, audible to all, in the middle of a play. The response from the audience to the performance is in some ways more direct – they can comment in the chat and will often be very honest in their comments; and in other ways more distant – a standing ovation has to be typed into the chat, which is less of a loud emotional outpouring.

RP: I find it ironic that you named your performance group “Avatar Body Collision,” which seems to complicate the idea of net space as a virtual medium for disembodiment. How do you see “avatar bodies” colliding on the Internet?

HVJ: I don’t think of virtual space as being disembodied. We are still in our bodies, we are using our bodies to create the performance – primarily our hands and fingers (digits – we say “break a digit” before our shows instead of “break a leg”). The collision in the name is not about bodies colliding with bodies, but avatars colliding with bodies. Where does my body end and my avatar begin, and vice versa? And how do other bodies, e.g. the audience, respond to my avatar? The collision is one of flesh and technology, sweat and pixels.

RP: Online, the audience or “cyberformience” plays a participatory role in the event, like the early Happenings from the 1960s. How does this non-hierarchical approach to theater impact the works you have created for the medium: how do you incorporate the audience into the work?

HVJ: It varies from show to show; some are designed for the audience to watch and respond, while others aim to actively involve the audience (cyberformience) to the point of co-authoring. One example at the first end of the continuum is “a gesture through the flames“, which was a webcam performance I created in 2008 for Annie Abrahams‘ “Breaking Solitude” series. I used a Victorian toy theatre and a soundscape to tell a story, and the online audience improvised a narrative in the chat. I didn’t interact with them during the performance (I was too busy to type) and it was fascinating to see how they read what I was doing. At the other end of the spectrum are works like “make-shift” or the series “We have a situation!” which can’t happen without the active participation of the audience. In “make-shift” (2010-12, with Paula Crutchlow), the audience were involved in writing texts, operating the webcam, answering quiz questions, building kites from recycled plastic, and ultimately performing on webcam. The event was structured so that they were “warmed-up” for their participation, and because we were located in someone’s home there was a very informal and comfortable atmosphere which made it possible for people to do these things.

RP: You are currently creating a new work entitled “we r now[here]” for the Art of the Networked Practice | Online Symposium. The title can be read as no(where) or now(here). Tell us about your concept of Internet space and time.

HVJ: Space and time in the online world are very fluid for me. I frequently work with people in different time zones, and travel physically between time zones myself as well, so I’m often calculating time differences and negotiating meeting times around all of this. In some ways time is irrelevant. In other ways, it’s highly significant – for example, precise timing is very difficult to achieve. Lag is unpredictable, sometimes it can disrupt a carefully planned sequence but at other times it can make something unexpectedly brilliant.

RP: A recent work, “make-shift,” unites domestic environments via the Internet in live, free-form conversation between online and onsite participants. How do you achieve a sense of intimacy and play in the online social space of the work despite geographical separation?

HVJ: I think of cyberspace as a space; apart from all the common spatial metaphors that are applied to it, when I’m working or communicating with people online in real-time it feels to me that we create a space through our shared presence, words, and whatever else we are using. It’s a space that extends into and absorbs a little bit of the physical environment of everyone present. “make-shift” did this very explicitly – we asked the audience (online and on site) to describe where they were, and this built a collaborative space or environment that everyone had a shared sense of.

In “make-shift” we created intimate and playful environments in two separate houses. the participants in the houses arrived half an hour before the show began, and during this time we warmed them up with a few activities and explained things about what was going to happen. Usually there was also food and drink, and often the people already knew each other so it was already quite friendly and informal. At the start of the show we began by introducing everyone. Each house called out a greeting to the other house and the online audience (which we’d practiced as part of the warm-up activities), and then we invited the online audience to tell us “what’s it like where you are?” This question was deliberately a bit open-ended, so people could describe their surroundings, the weather, their day, their mood and so on. The online audience are already seated at the keyboard and ready to interact; often they would make jokes, add other comments and respond to each other. We had regular online audience members who knew the format so inserted their own commentary or embellished others’. From this beginning, we continued throughout the piece to give the audience tasks that encouraged their sense of empowerment and ownership within the piece, such as operating the webcam, and we encouraged those in the house to interact in the chat with the online audience. Some people were a bit shy or worried about doing the wrong thing, but they usually got into it fairly quickly and became so involved in the piece that they lost any self-consciousness. In the final scene, the group in each house performed a song to the webcam and created a tableaux vivant of a painting we had referenced throughout the performance, and when we reached this point in the show they were always keen to do this.

RP: With the Avatar Body Collision performance group, you have restaged Samuel Becket’s minimalist theater work “Come & Go.” Your approach to cyberformance has always been very free and open, and yet Becket is the opposite: highly structured with precise directions for actors. How do you reconcile these differences?

HVJ: It was a lot of fun to do “Come & Go“; from the outset we accepted that we had a strict set of instructions to follow, and made that our task – to render Beckett’s directions in cyberformance as faithfully as possible. So we didn’t reconcile those differences, rather we saw it as an opportunity to work differently for a change. We worked on small but precise avatar movements, which is harder than you might think, and used simple gestures that very effectively added emotion, such as a turn of the head or holding a hand up to the mouth. We played with the text2speech voices of our avatars: I was Flo, who at one point has the line, “Dreaming of … love”, and we discovered that the “…” created an emotional quaver in the computerised voice when it said “… love”. This was both funny and tender. So having a script and such precise directions meant that we spent time on details like this.

RP: You have produced your own online symposia, the Cyposium, the latest from 2012 culminating in CyPosium the Book, an edition of essays and transcriptions. How has your experimentation with the online symposium format altered your view of what a conference gathering can fulfill given global access via the Internet?

HVJ: The CyPosium was very successful and generated an exciting buzz. I think one reason for this was that everyone was online. When there is a stream from a proximal conference, it’s very easy for people at the physical venue to forget about those online. It takes very thoughtful planning to ensure that the online participants are fully included. So in the CyPosium, everyone was online and therefore equally included. Most people commented quite freely – at times it was quite dizzying to see the chat scrolling up at great speed, there was so much discussion. This made it quite difficult for the moderators to field questions – we had planned as best we could for this and it went pretty well, but there were so many people actively engaged in the discussion that at times we couldn’t keep up. Many people stayed online for most of the 12 hours, and the response was very enthusiastic the whole way through, which made it clear that there is a desire for this kind of event.

RP: In your years of performing and creating online performance, what do you think is missing in the liminal space of the online medium due to distance and non-corporeality? What do you yearn for? What do you still want to accomplish?

HVJ: At an absolutely practical level, I yearn for better funding, for funding opportunities that are not tied to geographical locations, as nearly everything still is. The distributed, non-corporeal and ephemeral nature of this work means that it’s always on the periphery – which in some respects is a wonderful place to be, but it’s usually the least-funded place.

There are many things that I imagine and would like to realise but can’t technically; some of these things may become possible if/when we manage the rebuild of UpStage that we are planning. But often what interests me most is experimenting with the resources I have and discovering what’s possible; what tricks or hacks I can do, what surprises there are when we push a technology in a way it wasn’t intended to be pushed or when we use a tool differently.

What I would still like to accomplish in my work is to further develop the intentions of shows such as “make-shift” and “we have a situation,” where a creative process shared by audience and artists can ultimately effect real change, at the individual level and socially/politically. I’m interested in how cyberformance can facilitate meaningful discussions and encourage people to think about alternatives and make actual changes in their lives. I’m interested in how connections between remote and apparently unrelated people and contexts can open up new possibilities.