Mark Hancock discusses the politics and artistry of Janez Janša’s identity interventions in the context of their recent challenge at the Parliamentary Elections in Slovenia, in June 3rd 2018.

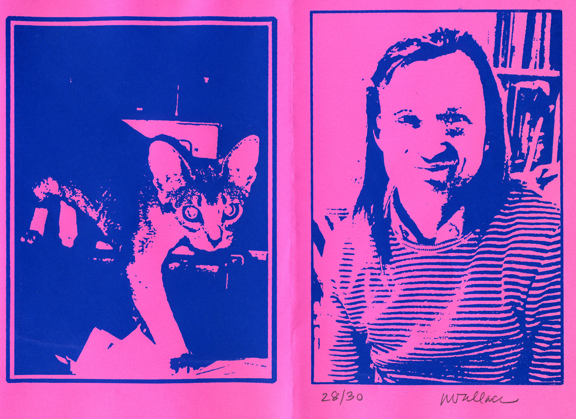

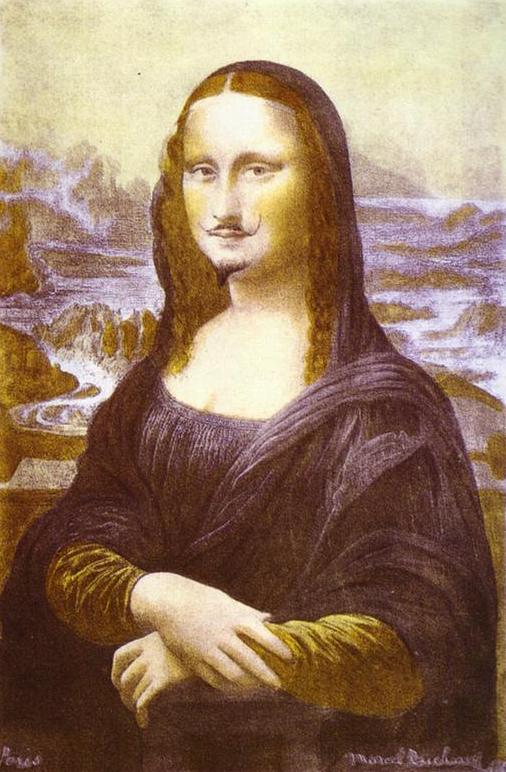

Ideas firmly deduced, tested against all variables and tentatively sent out into the world for appraisal by others, soon betray us as they bend to the whims of anyone they encounter. But that’s the nature of the malleable, post-digital world we live in. Ideas have to adapt and change to suit the warp and weft of the society if they are to survive in some form. How do we lock down our ideas into their final form? And what level of commitment can we expect from our ideas even if we apply intellectual property rights and that centuries-old mark of authenticity, the signature? The art world is particularly vulnerable to the conceit of signed authenticity. A signature often being the only guarantee that you’ll see any return (financial, reputational or otherwise) on your investment. If you really want to play with systems of power and bureaucracy, try altering artist names.

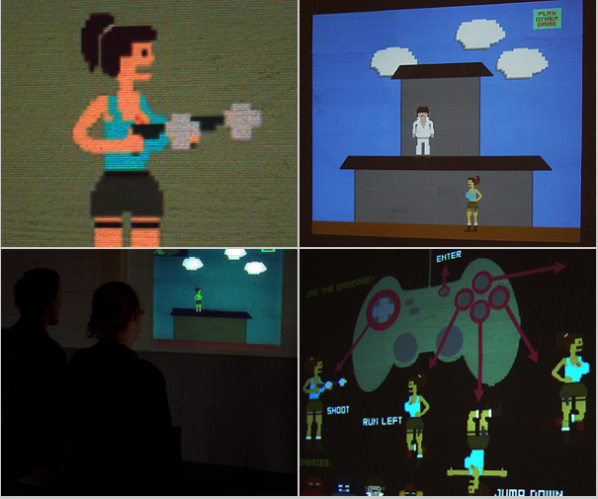

Davide Grassi, Emil Hrvatin and Žiga Kariž all changed their names to Janez Janša in 2007, joining the conservative Slovenian Democratic Party (SDS) at the same time, to explore the bureaucratic and political systems of their home country, Slovenia. The foundation of their actions ever since has been the question: what power exists in a name? And not just the art power system, but what political forces come into play when that name also belongs to the leader of the Slovenian Democratic Party, Janez Janša, (Prime Minister 2004 to 2008 and then again in 2012 to 2013). Incidentally, or perhaps not, Janez Janša, the politician was born Ivan Janša. The renaming of the three artists becomes a sort of double bluff when you also start to ask who the ‘real’ Janez Janša is.

It would be easy to assume that the work of Janez Janša is simply another playful, flaccid baiting of the art world and right-wing political hegemonies. All too often work that challenges the political system might as well be challenging the rules of the Italian Football League, for all the difference in the world it makes beyond the enclosed loop of the art community. There’s only so far that insulting the work of Damien Hirst with another work of art can get you. But the Janez Janša artists have chosen to pierce through the membrane of the art world and make a social difference.

In the Slovenian Parliamentary Elections on the 3rd June 2018, one of them ran as a member of the opposition party, Levica (The Left) in Grosuplje the home district of the ex-Prime Minister, Janez Janša. In a press release, Janez Janša (the artist) said: “Running for parliament is a logical consequence of the view I have towards society. I care about what is happening. I react to things. I want to change them. (…) Society must be organized in such a way that the state begins to serve its citizens, as opposed to serving capital. Capital has no interest either for society or for art or for the individual.”

There is something inherently political in multiple authors using a single name, at least if you cast an eye over recent history. Reference points include Wu Ming, the Italian author collective that produced a number of literary works (they published a best-selling novel, Q, in 1999). They evolved from the Luther Blissett collective, whose playful, socially engaged activities defy the concept of the singular creative voice. This concept seems so alien to much of the mainstream media, particularly in Wu Ming’s home country of Italy, where they have been accused of everything from cybercrime to the less savoury aspects of rave culture. It’s this uncertainty about ownership that seems to bring a nervous lump to the throat of media and political gatekeepers. Perhaps this revolves around two questions so central to capitalism: If you’re doing nothing wrong, why hide behind a nom de plume or a collective? And, who do I send the check to, if I want to buy an Art?

On top of this, copyright issues become complex when the roster of names increases as well. Because we still want ideas to be owned, even when they are expanded through homages and pastiches. Copyright, as the attorney representing the Janez Janšas points out, is a legal construct, protecting, “original artistic (and scientific) creations, which are expressed in any way. A work is protected by copyright only if it was created by a human being (an author) and bears a stamp of author’s personality.” With work by Luther Blissett and Wu Ming, at least the authors can be understood as ‘artists’, even anonymously. Janez Janša, Janez Janša and, last but not least, Janez Janša have layered this authorship of their artwork with another layer of copyright/ownership complexity.

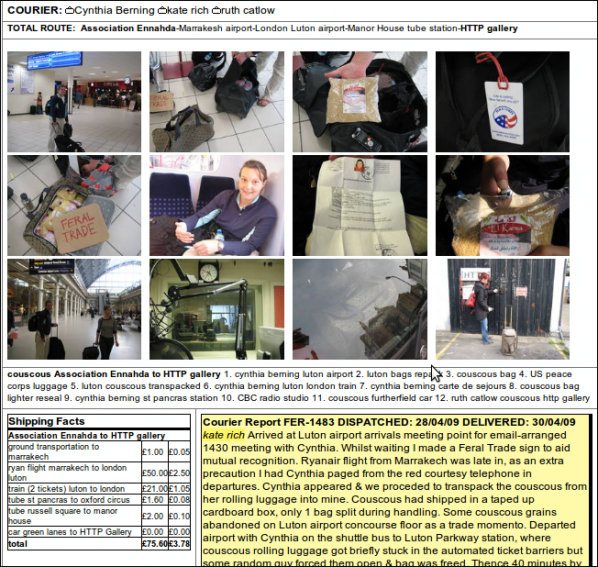

They refer to this work as collateral art, a phrase resonant with the phrase collateral damage, used to describe the acceptable casualties of battles. Collateral art is the acceptable damage on their ideas and projects from engagement with companies and institutions: ID cards, membership cards, the whole panoply of detritus that comes with the work. The artists want this collateral art, often customised by companies on request, to question the relationship between artworks and functional objects, “exploring post-Fordist means of production.” Any art historians still trying to shoehorn the belief of the gifted singular genius crafting his (note the gender pronoun: now discuss) solo masterpiece, probably hasn’t been paying close enough attention. The individual work of art often only becomes such with the signature of the artist attached as providence. When the work of art carries the signature of a non-artist though, can it still be brought into the art world as a valid comment on… anything? Paperwork sent to institutions by Janez Janša, and signed by an official becomes art. But whose art?

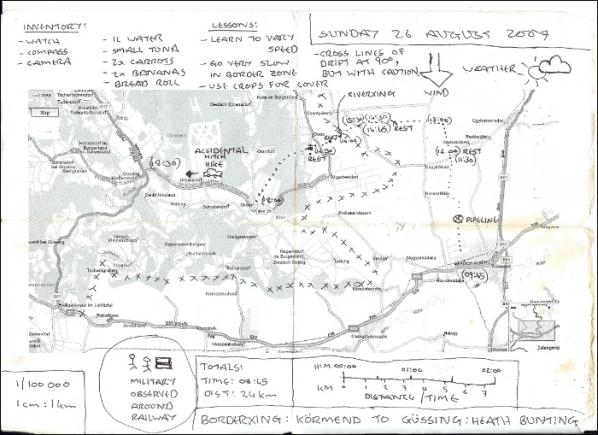

The answer, of course, is that it is their art. Whatever bureaucratic grindstone the works have been milled under, they ultimately belong back with the artists. It is they who return the work back to the art world through the exhibition. The exhibition co-produced by Moderna galerija (MG+MSUM) and Aksioma – Institute for Contemporary Art, Ljubljana, and curated by independent curator Domenico Quaranta, in 2017, was a chance to display and reflect back on ten years of work by the artists. Called the Janez Janša® exhibition, on display were works including Signatures (2007 – ongoing) which explored interventions of the Janez Janša name into public spaces, such as the Hollywood Walk of Fame (Signature, 2007), or Signature (Copacabana), in Rio de Janeiro, 2008. Playfully appearing in numerous locations around the world. Or Mount Triglav on Mount Triglav, an action performed in August 2007. This action commemorated “the 80th anniversary of the death of Jakob Aljaž; the 33rd anniversary of the Footpath from Vrhnika to Mount Triglav; the 5th anniversary of the Footpath from the Wörthersee Lake across Mount Triglav to the Bohinj Lake; the 25th anniversary of the publication of Nova Revija magazine and the 20th anniversary of the 57th issue of Nova Revija, the premiere publication of the SLOVENIAN SPRING; this was a re-enactment of Gora Triglav (Mount Triglav), by the OHO group in 1968 and the latest in a chain of re-enactments, as it was also performed by in 2004 by the Irwin Group.

The conference in the same year, Proper and Improper Names: Identity in the Information Society conference, hosted by Aksioma – Institute for Contemporary Art, Ljubljana, and curated by Marco Deseriis in 2017, invited speakers including Natalie Bookchin, Marco Deseriis, Kristin Sue Lucas, Gerald Raunig, Ryan Trecartin, Wu Ming. The subjects under discussion arose from Marco Deseriis’ book Improper Names: Collective Pseudonyms from the Luddites to Anonymous. Deseriis, as keynote speaker, talked about the genealogy of the improper name. This is Deseriis’s term for the use of pseudonyms by artist collectives, including Wu Ming (who presented a talk at the conference) and Ned Ludd, the fictional leader of the English Luddites.

Releasing your ideas out in the wild doesn’t always guarantee they will come back to you unscathed or even return at all. The works of the Janez Janša collective are sent out to corporate systems, being adapted and altered, and returned. Or at the very least offering a challenge to accepted forms of ideological structures. In the Slovenian elections on 3rd June, the Slovenian Democratic Party (SDS) won with 25% of the votes. Levica won 9.0%. The SDS is a far-right, anti-immigration party, reflecting the increasing rise of right-wing parties across Europe right now. The leader of the SDS, Janez Janša, now has the opportunity to form a right-wing government. If this happens, and by the time you read this, it may well have, it would continue the shift in European Councils members towards the right.

There’s nothing new in declaring that everything is in flux. That’s the nature of our hyper-accelerated world. But right now there is a creeping sense that The Other is also to be viewed as The Enemy. The social, political value of art has to change to mean something in what is little short of a battle for a better society for ourselves and others across the globe if it is to have any value whatsoever. Janez Janša, Janez Janša and Janez Janša’s work reflect this evolution by being part of the society around them. Being part of the electoral system reflected this challenge and desire to be part of the real world and to make art mean something more than gallery space and conference papers. If art wants to survive and continue to belong to everyone, then it needs to be part of the world we are living in right now. No one work of art ever changed the world, but it helps us unravel and see through the propaganda of systems. We all need to become Janez Janša®.

The final outcome of the recent Slovenian Elections remains uncertain as Social Democratic Party’s Janez Janša attempts to form a coalition government.

More images at Flickr – https://bit.ly/2yniHYL

More about Janez Janša – http://www.janezjansa.si/about-jj/

Featured image: Pandora’s Dropbox by Matt Bower

The Disruption Network Lab (DNL) has been presenting in Berlin some of the finest platforms for the discussion of art, hacktivism and disruption, presenting academic debates on not-so-conventional forms of thought. In their event IGNORANCE: The Power of Non-Knowledge, the second in the series Art and Evidence, various scientists and researchers discussed ignorance, not merely as a subaltern issue but as a central tool in knowledge production.

In previous events, DNL debated how ignorance is deployed as a mechanism of truth and power negotiation, mainly through the omission of the known by the means of secrecy, obfuscation and military classification. There are many forms of understanding ignorance, and this program intended to elucidate the potentialities and pitfalls within the concept. According to DNL, the first step towards approaching ignorance is to recognise it and become aware of it. As co-curator of DNL Daniela Silvestrin said (despite the paradox) that it is necessary to render the “unknown unknown into a known unknown.” The field of ignorance studies investigates the spread of ignorance, what kind of forms it takes depending on the context, how science “converts” it into probabilistic calculations of risk, and even how it can be used to push certain political, economical or religious agendas.

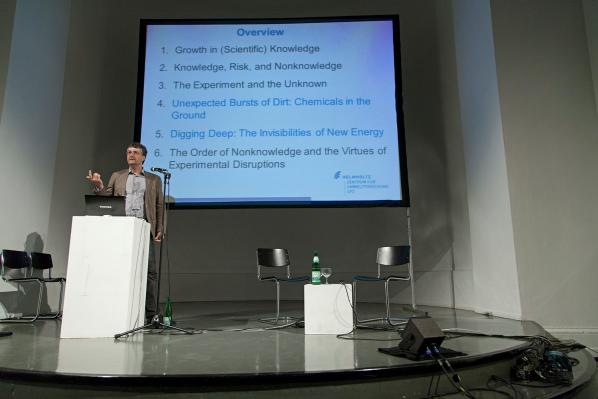

In the opening keynote, Matthias Gross, a sociologist and science studies scholar who has written extensively on ignorance studies, co-editing with Linsey McGoey the “Handbook of Ignorance Studies,” starts by stating that “new knowledge always creates new ignorance” and that throughout history humans have been in constant relation – acceptance, denial, resignation – with the unknown. Gross has covered how ignorance operates in different scientific milieus, namely, how risk is widely used in natural sciences as an attempt to project an idea of the future, as demonstrated in weather forecasting, but also how not knowing operates in everyday life; through secrets, the spread of false knowledge, feigning ignorance, or even through actively not wanting to know.

Gross presented a compelling body of research, exposing numerous examples in which ignorance serves the purpose as a tool to acknowledge what we don’t know in science (important in fields such as Epidemiology) or how positions of power use ignorance to manipulate public opinion within our social structures. However, the debate felt somehow stranded in an optimistic loop, where ignorance was seen mostly as a catalyst to search for further knowledge. Yet, I believe, while duelling with the binary knowledge vs ignorance, one should never forget to tackle the universalistic shape that ‘knowledge’ tends to adopt. In the end, the discussion felt insufficient, failing to examine knowledge/ ignorance from a non-hegemonic perspective when it would have been interesting to borrow criticism from postcolonial or feminist thought.

The first panel, moderated by Teresa Dillon, was deemed to shake the consensus in the room by joining the moralistic perspectives in science, the forbidden and undesired, the paranormal and the apocryphal together. Sociologist Joanna Kempner presented astonishing research focused on ‘negative knowledge,’ described as taboo, dangerous or threatening to the status quo. In an attempt to demystify the neutrality of knowledge production in sciences, Kempner interviewed various scientists to discover forbidden areas in their fields. The outcome of this research revealed that due to a fear of loss of funding and/ or sullying their reputation, scientists restrain themselves from researching illegitimate topics. For example, in Psychology one is expected not to study extra-sensory/ paranormal senses as these studies are usually associated to parasciences, a term that is in itself revealing of the hierarchies of knowledge. Kempner also exemplified how knowledge production is pressured by political interests and recalled the research-bans during the G.W.Bush government that cut funds to research related to sex and drugs under the assumption that remaining ignorant about any possible positive aspects (of recreational drug consumption) guarantees the maintenance of conservative moral values.

On the maintenance of moral values, the philosopher Jan Wieland presented an interesting experiment: “What would you do if you wouldn’t know? And what would you do if you’d know?” Giving the example of a social experiment by Fashion Revolution, a movement that calls for “greater transparency in the fashion industry”, Wieland examined consumers’ choices as they acknowledged the conditions in which clothing is actually produced. The project invokes a sentimental story with an excerpt from the daily life of a young girl living in Dhaka, Bangladesh, who works in a garment factory. Coming to terms with the girl’s story, the reactions differed — from not buying and empathically connecting with her situation to total indifference and still buying. Wieland attempts to analytically evaluate their intentions, good or bad, and how ignorance affects choices, stating that some of us might willfully remain ignorant (willful ignorance) as a way to better cope with our habits of consumption. However, I find it difficult to extrapolate these findings to a moralistic and individualistic criticism of people’s consumerist choices, since we know there is a structure that keeps consumers far from well-informed. A good example of how economy capitalises on ignorance, we know that the international division of labour is intentionally built to alienate the consumers from the “dirty” phases of production.

Jamie Allen, artist and researcher, also analyses at the economy of non-knowledge that is in the genesis of apocryphal technologies. “Do pedestrian’s crossroads’ buttons actually work?” We have all thought about this, yet has it stopped us from pressing the buttons? As long as we do not know whether a certain technology actually works, it “works”. Such an economy is boosted by acknowledging that some things remain as common ignorance. If we are not sure whether a lie detector works or not, then it can be used to incriminate — amidst ignorance, it shall produce the truth.

Informative and somewhat frightening, “Merchants of Doubt”, directed by Robert Kenner (2014), reveals how bendable ‘truth’ is in the interests of big corporations. The documentary investigates how the tobacco industry spread false information among firefighters, leading the world to believe that the domestic fires caused by cigarettes were the fault of the furniture rather than the cigarettes. This is where it goes from uncannily funny to scary. While interviewing scientists, whistleblowers and activists, the film unveils the dreadful story of corporate campaigns designed to unleash confusion and scientific scepticism among the masses, putting the life and security of millions at stake. This scepticism is not passive, thus it turns into a cynical endeavour. As corporations claim that there is no consensus surrounding issues such as global warming, conferences and books are forged to sustain their statement, while scientists who defend the existence of greenhouse gases are accused of ceding to their political biases in order to get funding for their research. What about facts? They seem to become irrelevant in the face of expensive lies.

Watch Merchants of Doubt’s trailer here.

Karen Douglas, a social psychologist, presented an empirical study of conspiracy theories whilst trying to trace a particular psychological profile of those more prone to elaborate and believe in them. Douglas used widely known conspiracy theories as examples, such as the infamous car crash that killed Princess Diana (which became a true “Schrödinger’s cat” case, instigated by the media-produced hyperreality in which Diana was both alive and dead — along with Elvis Presley) and the theory that 9/11 was orchestrated by the United States government to instigate and justify the “war on terror”. Douglas believes we are naturally hardwired to believe in conspiracy theories and sees them as a way to cope with things we are unable to answer. A socio-analytical view on conspiracy theories also seems to fail the complexity of forces that make us consider why certain theories are conspiracies and other perspectives are just theories. The issue with Douglas’ approach lies within its socio-psychological analysis, which tries to find a pathological pattern in people who believe in conspiracy theories, such as describing these people as being intentionally biased, or stating that those who tend to perceive patterns in things or believe in more than one conspiracy theory all show the “symptoms” of a conspiracy theorist. Yet, as pointed out by a member of the audience, this approach seems to lack a sensibility to the entire concept of “conspiracy theory” as a political tool to dismiss and undermine other narratives, such as narratives from an undesired other (e.g. how Russia’s government agenda is seen by the USA). Nevertheless, it is interesting to understand how these bodies of “disbelief”, should you wish to call them conspiracy theories or not, have a huge impact on our lives and inevitably our deaths (e.g. global warming, vaccination). As with apocryphal technologies, certain forms of unknown seem to crystallise as forms of knowledge – we know that we do not know and that is the way it is.

The closing panel, moderated by Tatiana Bazzichelli, has overseen our entanglement on social media and its algorithms, promising to be oracles of truth while their complex structures grow beyond our understanding. Ippolita, a group of activists and writers, warned how social media promotes emotional pornography, where our feelings are exploited by click baits in exchange for our personal data. By establishing clear metrics of interaction, like the number of likes and comments, social media creates an addictive game of forged interactivity, while we are scrutinised by biometric evaluation resultant from the same data we produce. Also analysing the manipulation of data and its weight in political agendas, Hannah Parkison, a journalist focused on digital culture, analysed Trump’s run for presidency propaganda in digital media. By using mostly social networks, such as Facebook and Twitter, Trump has kept control of his narrative without entering into risky interviews broadcast on TV. This is an effective way to get away with lies, regardless of the constant warnings from fact checkers – according to Politict 78% of what Trump said on the run for the election is not factually true. These lies spread across the internet, rendering their own truth.

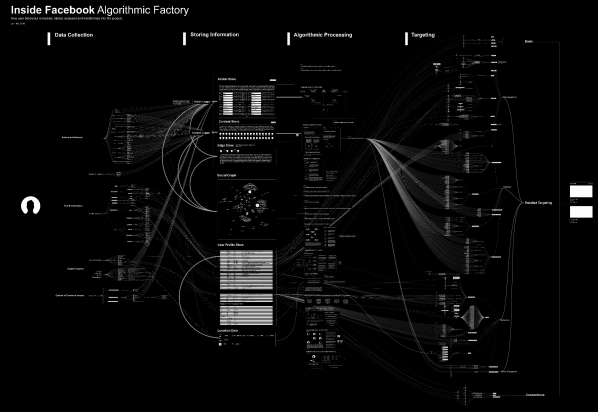

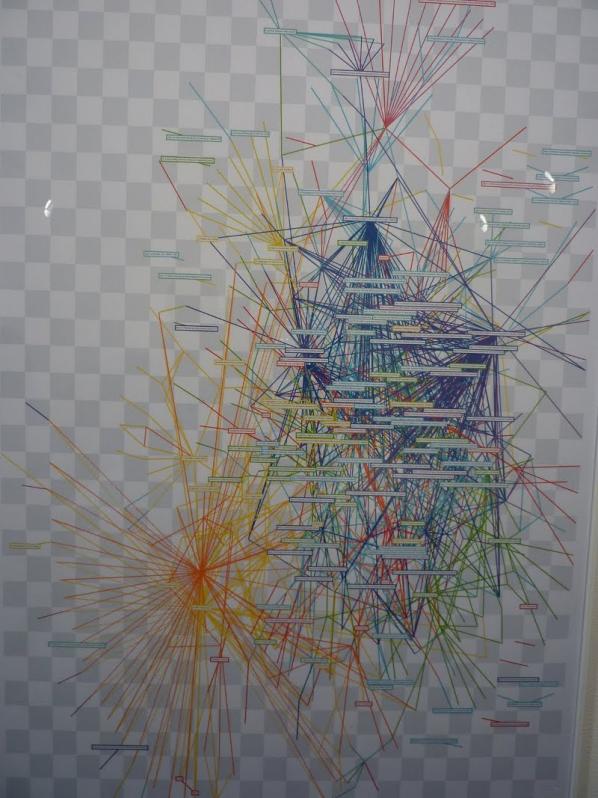

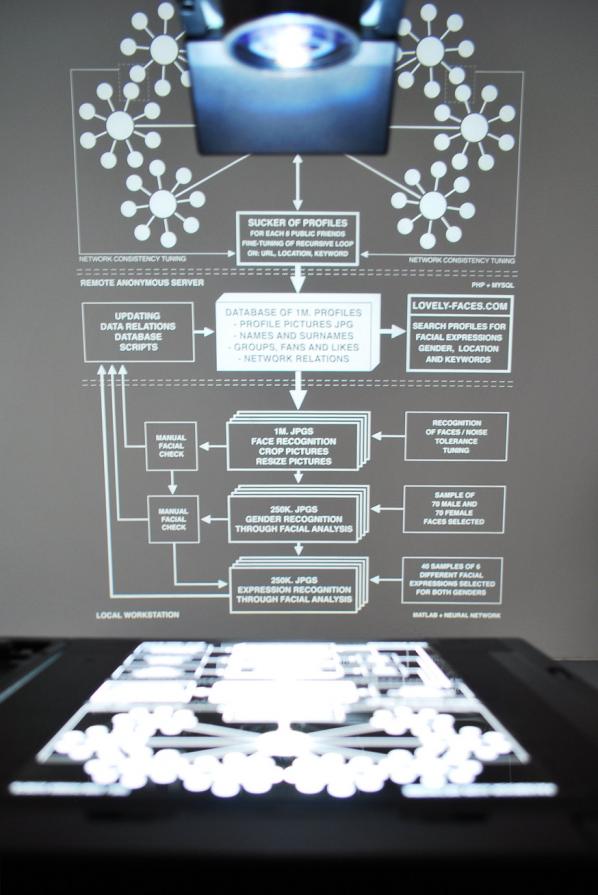

Vladan Joler, chair of New Media Department at the University of Novi Sad, presented his project in which he tries to map the tentacular structure of the Facebook algorithm, an expansive database incorporating individuals’ personal information that implies the fabrication of assumptions about potential consumers’ habits, wants and needs. Facebook was thus framed as an immaterial factory of information, the functioning of its assembly line still unknown, constantly mutating and growing. A speculative visual image of Facebook’s processes was rendered as Vladan tried to map something unknown; this mapping has similarities to the work of early cartographers. And much like early anthropological stances, the nodes of information produced have the potential to define thoughts and discussions about what we are and how we are supposed to behave. As Vladan ironically concluded, these are the tools used by the cybernet dominators – the digital monarchies that will accentuate asymmetries.

Ideas such as ‘knowledge’ find resistance and defiance from other epistemes that fall out from the western-centric productions of knowledge, such as the Amerindian ‘perspectivism’ defended by Viveiros de Castro or even the Alien phenomenologies (see Ian Bogost) that instigate the thought of non-anthropocentric ontologies. Bearing those in mind, I found that talking about the ‘dark’ side of knowledge is an invitation to dismantle and boycott its mechanisms of production, sustained in frail ideas of “truth”, “reality”, or “science”. In addition to the initial concept of ignorance, the conference provided a fertile ground for questioning the multiple ways in which humans deal with intangible phenomena, try to bypass obscurity and profit from that same obscurity. It provided insight on the relevance of knowledge to map and create reality, while bodies of power render webs of mystification of the tangible – corporations forging lies, politics of manipulation, cultural colonisation – reproducing ad nauseam epistemic violence.

The third edition of the Art and Evidence series from Disruption Network Lab, which took place on the 25th and 26th of November, wrapped up with the event TRUTH-TELLERS: The Impact of Speaking Out. TRUTH-TELLERS asks a question that could not be more crucial at the moment: “Can we trust the sources and can the sources trust us?” We have recently experienced a presidential battle between Clinton and Trump in which one of the most divisive topics were the thousands of emails sent to and from Hillary Clinton’s private email server while she was Secretary of State. A battle from which Trump left victorious despite having failed almost every fact-checking test. While Assange is forbidden to use the Internet for fear of him interfering with the presidential run in the USA, Chelsea Manning remains convicted, sentenced to 35 years of imprisonment due to her 2013 accusations of violating the Espionage Act. DNL gathered hacktivists, privacy advocates, investigative journalists, artists and researchers to “reflect on the consequences of leaking and whistleblowing from a political, cultural and technological perspective”. Unfortunately, due to a lack of funding, this could have been the very last DNL event. Let’s hope not, as these are vital, particularly in times of political despair.

I arrived at the Transmediale festival late Friday afternoon, which was hosted as usual at Das Haus der Kulturen der Welt (The House of World Cultures) in Berlin. The area where the building is sited was destroyed during World War II, and then at the height of the Cold War, it was given as a present from the US government to the City of Berlin. As a venue for international encounters, the Congress Hall was designed as a symbol of ‘freedom’, and because of its special architectural shape the Berliners were quick to call the building “pregnant oyster” [1] The exterior was also the set for the science fiction action film Æon Flux in 2005. Both past references link well with this festival’s use of the building. I remember during my last visit, in 2010, standing outside the back of the building watching an Icebreaker cracking apart the thick ice in the river. The sound of the heavy ice in collision with the sturdy boat was loud and crisp. This sound has stayed with me so that whenever I hear a sound that is similar I’m immediately transported back to that point in time. Unfortunately, this time round there was no snow, instead the weather was wet, warm and slighty stormy.

Last year’s festival explored the marketing of big data in the age of social control. This year, the chosen format was entitled conversationpiece, with the aim of enabling a series of dialogues and participatory setups to talk about the most burning topics in post-digital culture today. To give it grounding and historical context the theme was pinned to the “backdrop of different processes of social transformation, 17th and 18th century European painters perfected the group portrait painting known as the “Conversation Piece” in which the everyday life of the aristocracy was depicted in ideal scenes of common activity.” In recent years the festival has scafolded its panels, workshops and keynotes to grand, central themes to guide its peers and visitors, along with a large-scale curated exhibition. If we view the four interconnected thematic streams- Anxious to Act, Anxious to Make, Anxious to Share and Anxious to Secure – we might guess that the festival curators are also anxious to save all the resources (and celebrations) for next year, which is after all, Transmediale’s 30th birthday.

So, I was curious to see how my brief time here would unfold…

This review is focused on the hybrid event Off-the-Cloud-Zone. It featured presentations, talks and workshops, starting at 11 am, going on until 8pm. Hardcore indeed. It demanded total dedication, which unfortunately I was not able to give. However, I did offer my attention to the rest of the proceedings from lunch time until the end. It was moderated by Panayotis Antoniadis, Daphne Dragona, James Stevens and included a variety of speakers such as: Roel Roscam Abbing, Ileana Apostol, Dennis de Bel, Federico Bonelli, James Bridle, Adam Burns, Lori Emerson, Sarah T Gold, Sarah Grant, Denis Rojo aka Jaromil, George Klissiaris, Evan Light, Ilias Marmaras, Monic Meisel, Jürgen Neumann, Radovan Misovic aka Rad0, Natacha Roussel, Andreas Unteidig, Danja Vasiliev, Christoph Wachter & Mathias Jud, and Stewart Ziff.

The Off-the-Cloud-Zone day event was a continuation of last year’s offline networks unite! panel and workshops. Which also originated from discussions on a mailing list called ‘off.networks’ with researchers, activists and artists working together around the idea of an offline network operating outside of the Internet. The talks concentrated on how over recent years there has been a growing scene of artists, hackers, and network practitioners, finding new ways to ask questions through their practices that offer alternatives in community networks, ad-hoc connectivity, and autonomous systems of sensing and data collecting.

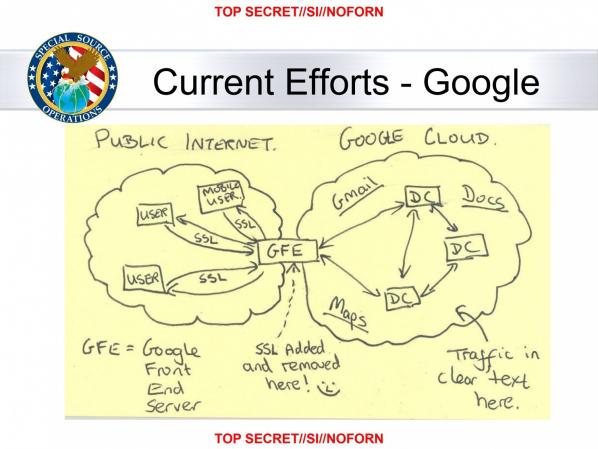

Disillusionment with the Internet has spread widely since 2013, when Edward Snowden the US whistleblower leaked information on numerous global surveillance programs. Many of these programs are run by the NSA and Five Eyes with the cooperation of telecommunication companies and European governments raising big questions about privacy and exploitation of our online (interaction) data. This concern is not only in relation to spying corporations, dodgy regimes and black hat hackers, but also our governments. “The idea of privacy has been flipped on its head. People don’t have to disclose their own information voluntarily anymore; it’s being taken from them regardless of their wishes.” [2] (Nowak 2015)

“The NSA’s principal tool to exploit the data links is a project called MUSCULAR, operated jointly with the agency’s British counterpart, the Government Communications Headquarters . From undisclosed interception points, the NSA and the GCHQ are copying entire data flows across fiber-optic cables that carry information among the data centers of the Silicon Valley giants.” [3] (Gellman and Soltani, 2013)

The above slide is from an NSA presentation on “Google Cloud Exploitation” from its MUSCULAR program. The sketch shows where the “Public Internet” meets the internal “Google Cloud” where user data resides. [4]

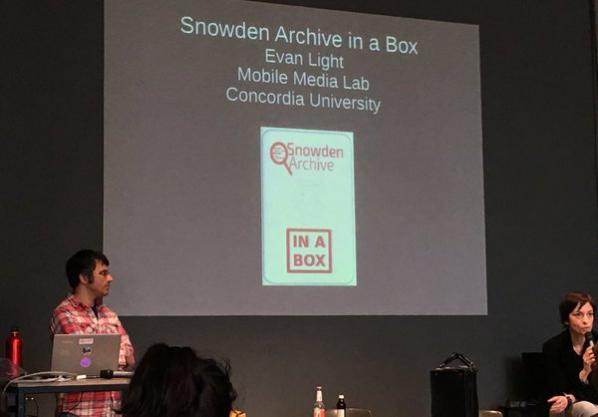

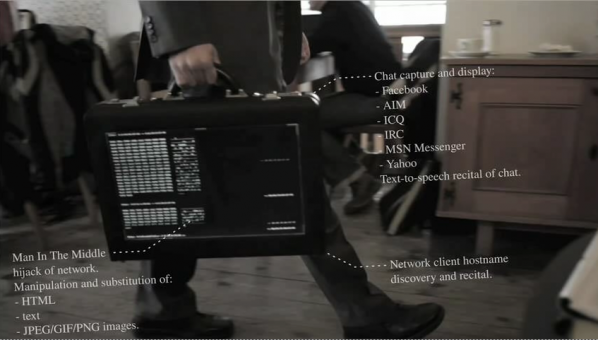

A legitimate concern for anyone wishing to read the contents of the leaked Snowden files, is that they will be spied upon as they do so. Evan Light has been working on finding a way around this problem, and at the Off-the-Cloud-Zone day event he presented his project Snowden Archive-in-a-Box. A stand-alone wifi network and web server that permits you to research all files leaked by Edward Snowden and subsequently published by the media. The purpose of the portable archive is to provide end-users with a secure off-line method to use its database without the threat of surveillance. Light says, usually the wifi network is open, but users do have the option to make their own wifi passwords and also choose their encryption standard.

Snowden Archive-in-a-Box is based on the PirateBox, originally created by David Darts who made his in order to distribute teaching materials to students without the hassle of email. It is based on a RaspberryPi 2 mini-computer and the Raspbian operating system. All the software is open-source and its most basic setup can run on one RaspberryPi. In his talk Light said that a more elaborate version would use high-quality battery packs and this adds power for autonomy, along with the wifi sniffer that is running on a secondary RaspberryPi and a flat-screen for playing back IP traffic. If you’re interested in building your own private, pirate Archive-in-a-Box, visit Light’s web site for instructions on how to.

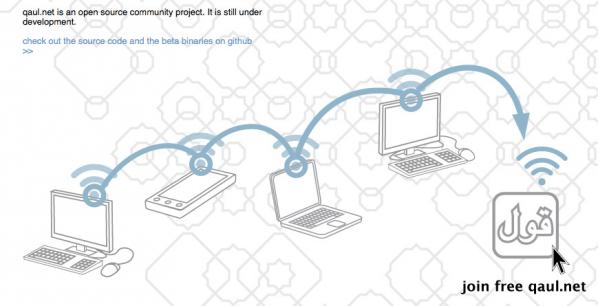

Christoph Wachter’s and Mathias Jud’s work, directly engages with refugees and asylum seeker’s social situations, policies, and the migrant crisis. They’ve worked together on participatory community projects since 2000 and have received many awards. For instance, take a look at their digital communications tool qaul.net which is designed to counteract communication blackouts. It has been used successfully in Egypt, Burma, and Tibet, and works as an alternative to already existing government and corporate controlled communication pathways. But, it also offers vital help when large power outages occur, especially in areas in the world suffering from natural disasters. The term qaul is Arabic and means ‘opinion, say, talk or word’. Qaul is pronounced like the English word ‘call’.

It creates a redundant, open communication code where wireless-enabled computers and mobile devices can directly initiate a fresh, unrestricted and spontaneous network. This includes the enabling of Chat, twitter functions and movie streaming, independent of Internet and cellular networks. It is also accessible to a growing Open Source Community who can modify it freely.

Wachter and Jud also discussed another project of theirs called “Can You Hear Me?”, a WLAN / WiFi mesh network with can antennas installed on the roofs of the Academy of Arts and the Swiss Embassy in Berlin, which was located in close proximity to NSA’s Secret Spy Hub. These makeshift antennas made of tin cans were obvious and visible for all to see. The Academy of Arts joined the project building a large antenna on the rooftop, situated exactly between the listening posts of the NSA and the GCHQ to enable people to directly address surveillance staff listening in. While installing the work they were observed in detail by a helicopter encircling overhead with a camera registering each and every move they made, and on the roof of the US Embassy, security officers patrolled.

“The antennas created an open and free Wi-Fi communication network in which anyone who wanted to would be able to participate using any Wi-Fi-enabled device without any hindrance, and be able to send messages to those listening on the frequencies that were being intercepted. Text messages, voice chat, file sharing — anything could be sent anonymously. And people did communicate. Over 15,000 messages were sent.” [5] (Jud 2015)

A the end of their presentation, they said that they will be implementing the same system at hotspots deployed in Greece by the end of the month. And I believe them. What I find refreshing with these two, is their can do attitude whilst dealing with political forces bigger than themselves. It also gives a positive message that anyone can get involved in these projects.

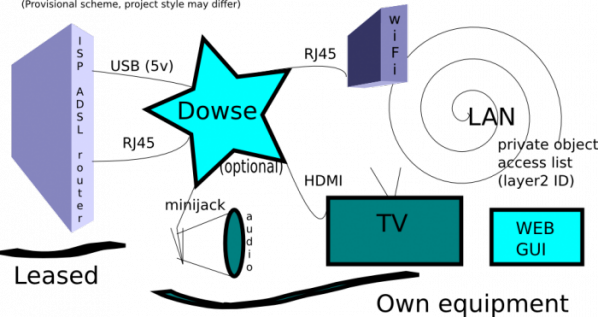

And then, it was the turn of the well known team at Dyne.org to discuss a project of theirs called Dowse, which is ‘The Privacy Hub for the Internet of Things’. They said (taking turns, there was about 5 of them) that the purpose of Dowse is to perceive and affect all devices in the local, networked sphere. As we push on into the age of the Internet of Things, in our homes everything will be linked up.

“Those bathroom scales and home thermostats already talk to our smartphones and in some cases think for themselves.” [6] (Nowak 2015)

As these ubiquitous computers communicate to each other even more, control over these multiple connections will be essential. We will need to know how to interact beyond the GUI interfaces and think about who has access to our private, common and public information. A whole load of extra information will be available without our consent.

Dowse was conceived in 2014 as a proof of concept white paper by Denis Rojo aka Jaromil. Early contributors to the white paper and its drafting process includes: Hellekin O. Wolf, Anatole Shaw, Juergen Neumann, Patrick R McDonald, Federico Bonelli, Julian Oliver, Henk Buursen, Tom Demeyer, Mieke van Heesewijk, Floris Kleemans and Rob van Kranenburg. I downloaded the white paper and is definitely worth reading.

The Dowse project aims to abide to the principles stated in the Critical Engineers Manifesto, (2011). Near the very end of the talk they announced to the audience an open call for artists and techies everywhere to get involved and jump into the project to see what it can do. This is a good idea. If there is no community to make or break platforms, hardware and software, then there is a limited dialogue around the possibilties of what a facility realistically might achieve. Not just that, they want artists to make art out of it. I know there are some pretty clever tech-minded geeks out there, who will in no doubt take on the challenge. However, once those who are not so literate in the medium are able to exploit the project, it will surely fly. It’s going to be interesting, because if you look at the 3rd point in the Critical Engineers Manifesto, it says “The Critical Engineer deconstructs and incites suspicion of rich user experiences.” I’m thinking, that this number 3 element needs to treated with caution. If they really wish to open it up to a diverse user base, to engage with its potentialities, creatively and practically; thus, allow new forms of social emancipation to evolve as ‘freedom with others’. There needs to be an active intent to avoid a glass ceiling based on technical know-how. It’s a promising project and I intend to explore it myself and see what it can do and will invite other people within Furtherfield’s own online, networks to join in and play, break, and create.

Our final entry is the Sarantaporo Project which is situated in the North of Greece. A village in the mountains just west of Mount Olympus in Central Greece close to Thessaloniki, Macedonia and Larisa. The country has been in recession for over 6 years now, and many communities have had to create alternative ways of working with each other in order to survive the crisis. Over this troubling period, new forms of grass-roots coexistence, solidarity and innovation have evolved. The Sarantaporo Project is an impressive example of how people can come together and experiment in imaginative ways and exploit physical and digital networks.

Even before the economic crisis the region was already hit by poverty, and with the added pressures of imposed Austerity measures, life got even tougher. All the young were leaving and then migrating to the cities or abroad. Before the project in Sarantaporo, there was no Internet nor digitally connected networks for local people to use. This situation contributed to the digital divide and made it difficult to work in a contemporary society, when so many others in the world have been using technology to support their civic, academic and business for so many years already.

“In Greece, where unemployment reaches 30% in all ages and genders, and among the youth overpasses 50%, immediate solution for the “social issue” is more than urgent.’ [7] (Marmaras).

“Besides maintaining the network in a DIWO (Do It With Others) manner, and creating an atmosphere of cooperation among far-flung communities that were previously strangers, the Sarantaporo network is incorporating different groups of people into the community, like Farmer’s Cooperatives and techies. It is also creating an intergenerational space for learning.” [9] (Bezdommy 2016)

To resolve this issue a group of friends decided to deal with this problem by setting up a community D.I.Y wireless network to provide free internet access to 15 villages in the municipality of Elassona. “Sarantaporo.gr is an open source wireless mesh networking system that relies greatly on voluntary work both for its development and maintenance. Some volunteers are involved in the project by simply installing an antenna on their roof. Others, more actively engaged with the project, are responsible for sustaining the network by hosting meetings and answering technical questions.” [8] (Kalessi 2014) The audience was presented with snippets from a film made by the filmmaking collective Personal Cinema, about the project. It was made so the story of Sarantaporo’s DIY wireless network gets a wider reach, and that others are also inspired to do similar projects themselves.

These projects are dedicated to creating socially grounded and engaged alternatives to the proprietorial, networked frameworks that currently dominate our communication behaviours. These proprietorial systems, whether they are digital or physical are untrustworthy, and control us in ways that reflect their top-down demands but not our common needs. This reflects a wider conversation about who owns our social contexts, our conversations, our fields of practice, the structures we use, the land, the cables, our history, and so on.

Looking at the state of the planet right now you’d be forgiven for betting on a future not far from the director Neill Blomkamp’s vision in the sci-fi movie Elysium where, in the year 2159, humanity is sharply divided between two classes of people: the ultra-rich whom live aboard a luxurious space station called Elysium, and the rest who live a hardscrabble existence in Earth’s ruins. However, in the Off-the-Cloud-Zone talks we encountered an ecology of strategies to protect our own indegenous cultures from the crush of neo-liberalism, we felt part of a grounded movement discovering new conversations and new methodologies that may provide some protection against future colonisation. Perhaps there is a chance, we can build and rebuild stronger relations with each other, beyond: privilege, nation, status, gender, class, race, religion, and career.

The festival this year was less structured and more nuanced than usual. It gave conversation a greater role and a deeper social context, and opened up the process for the many to connect with the ideas being explored. The whole affair seemed to be slowed down and less caught up in the hyper-macho trappings of accelerationism. It seemed less neurotic and spending less effort to impress. I’m sure, next year, on it’s 30th anniversary, all will be sharp and amazing. However, I liked this less glossy, more messy version of Transmediale and I hope it manages to impress the wrong people again, and again.

Featured image: The facade of Kunstquartier Bethanien. Image by Nadine Nelken.

After a full year of events focusing on several topics, from drones to surveillance, cyberfeminism to hacktivism, or even the famous Technoviking and a hot debate on the politics of the Porntubes, the Disruption Network Lab wraps up 2015 with its event STUNTS, focusing on political stunts, interventions, pranks and viralities. It was a year of great success for the DNL and proof of that was a full house, in the middle of a cold Berlin winter, full of people eager to take part of this last gathering on art research, hacktivism and disruption.

Just at the entrance, in the castle-like facade of Kunstquartier Bethanien, the Free Chelsea Manning Initiative projected a video including phrases of support, denouncing the system that violently charges against all the whistleblowers who bravely stand against state-crime. Chelsea Manning, sentenced in August 2013 to 35-years of imprisonment, turned 28 years old on the 17th December. The initiative took the occasion to celebrate her anniversary but also to remind us of her cause and of how vulnerable whistleblowers are under the purview of “justice”.

Peter Sunde, one of the founders of Peter Bay, has recently given an interview stating “I have given up” when asked about the current state of free and open internet. The pessimistic tone that might loom among hacktivism has its reasons. With a growing and raging state surveillance, invigorated politics of fear veiled as anti-terrorism propaganda, or the alienating neoliberal order, the seemingly scarce possibilities to fight back can be easily overtaken by a sense of hopelessness. Yet, the proposal of STUNTS claims the possibility of new futures; suggesting that new artistic militancies and political subversions of neoliberal networked digital technologies, hoping to provide a glimpse of another world. What can be done? There’s still a lot to be done.

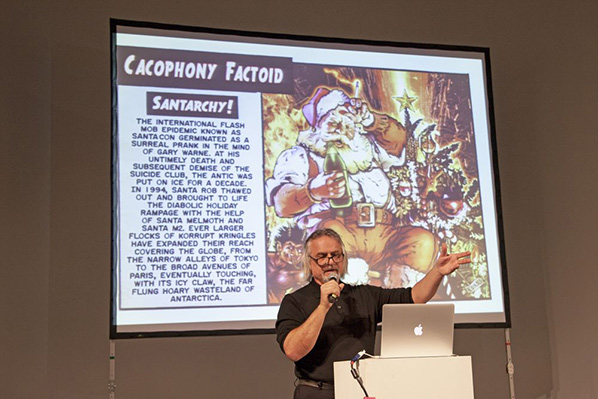

The opening keynote was reserved to John Law, original member of the Suicide Club and Cacophony Society, and one of the initiators of the Burning Man Festival, who gave an inspiring speech condensing 40 years of disruptive movements in the city of San Francisco. Law highlighted how important it was to live in San Francisco, a well-known refuge for many weirdos, hippies and punks, and how the city served as fertile ground for the foundation of many movements of disruption, such as the Suicide Club or the Cacophony Society.

The Suicide Club, born from a course at the Free School Movement (also known as Communiversity) in the late 70s, was one of the pioneers with its events of urban exploration, street theatre and pranks. For several years, its members engendered actions of occupation and appropriation of public spaces, aiming to subvert the order of these spaces and highjack the authorities. Later on, some of its members founded the Cacophony Society which followed the same footsteps, creating social experiments and stunts, which according to Law didn’t necessarily mention being political but instead playful acts of liberation from the norm. Yet, in an age of overwhelming neoliberal labour exploitation, we can wonder if having fun among the working class isn’t already a political act. As Law said, “the events were illegal but not immoral” reminding everyone that in ethics and politics of disruption, right and wrong should never be defined by law. It seems that disruption is intrinsically political in the sense it questions the ruling order while also being an emancipatory act of dissidence.

PANEL: STUNTS & DUMPS – THE MAKING OF A VIRAL CAUSE

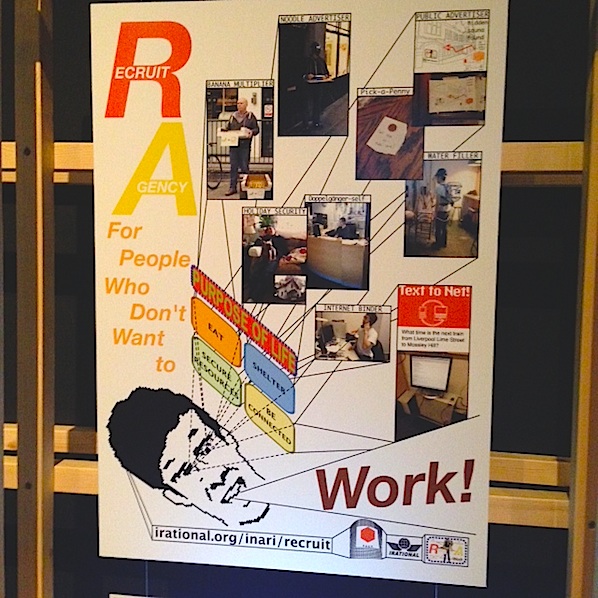

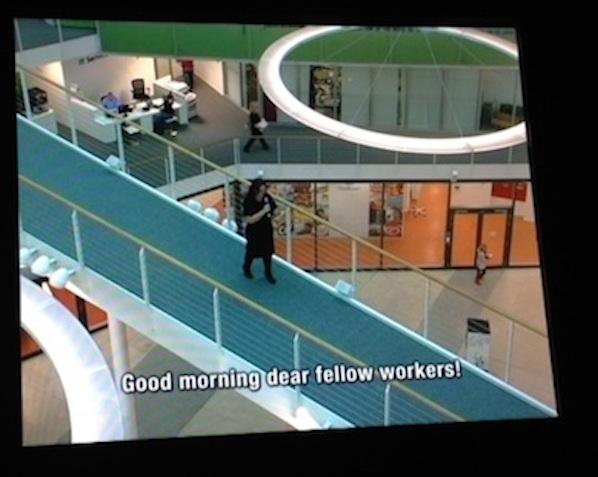

The panel, moderated by Ruth Catlow, one of the founders of Furtherfield, included a group of four hacktivists and disruptors, two of whom claimed to have once been Luther Blissett, an open-pseudonym used by several artists and activists as an hoax who has taken credit and responsibility over several stunts and pranks over the past 20 years. Following the thread of adopting an emancipatory praxis in the demand for privacy, M.C.McGrath presents the Transparency Toolkit. Motivated to refuse of data collection and the brute quantification that intelligence and corporations enforce as an interpretative lens for evaluating people’s lives, with this toolkit McGrath intends to facilitate the access to a database that allows journalists and civilians to surveil the surveyors. Providing easy access to personal data of the intelligence community, he gives intelligence a taste of its own poison. In response to the predictive justice portrayed by nowadays algorithmic supremacy, the Transparency Toolkit disturbs the power asymmetry while possibly enabling for even some form of critical mob justice.

Andrea Natella, creative director of guerrigliamarketing.it and KOOK Artgency, seeks for justice by creating elaborate hoaxes that corrupt corporate advertisement. Hoaxes such as the fake air company Ryanfair which claimed to “welcome aboard refugees” under the Geneva Convention, enabling refugees to fly without a visa. The ingenious mockery resulted in a flamed response from the ‘real’ company debunking the advertisement while at the same time it has received a great attention from the media, resulting in a broader public discussion on the refugee situation. Once again, Natella presents us with the power of disruption by taking advantage of tools used by the prevailing order.

The undergraduate in Computer Sciences Mustafa Al-Bassam has gained notoriety for being a part of LulzSec, a computer hacking group responsible a number of high profile attacks, resulting in being legally banned from the Internet for two years. From an early age Mustafa focused his time in the creation of tools to unmask the tenacious mechanisms of domination. From ironically proving the negative correlation between tests scores and the amount of assigned homework to denouncing violations of online privacy and security perpetrated by state agencies such as the FBI, Mustafa has been a main character in the defence of human rights in the post-digital era.

To close the panel, Jean Peters, co-founder of the Peng! collective, shifts the perspective of the debate. What if instead of blaming or attacking members of intelligence we could provide them the tools to liberate them from their own institutions? Recognising that within the intelligence community resides a great number of whistleblowers, Intelexit, which started as a hoax, is now an initiative that helps people leave the secret service and build a new life. Aimed specially at members of agencies such as CGHQ or NSA, Intelexit offers safe and encrypted channels of communication through which intelligence members can get access to legal and moral support. Without the intention of dismissing responsibility of these members, claiming some banality of evil, by emancipating intelligence members Intelexit conceives another possibility to disrupt the system from within.

CELEBRATING AT SPEKTRUM

With an incredible array of playfully disruptive tools and practices, the ending tone of the panel is of hope and optimism. Maybe this is the kind of optimism that inspired Chuck Palahniuk into writing the Fight Club, clearly influenced by the Cacophony Society of which he was a member. Optimistic disruption seems to pave way to new worlds of possibilities, into a new future envisioned with the help of DNL.

To close STUNTS in an even more optimistic way, the celebration of a year of DNL was at SPEKTRUM, another outstanding initiative in Berlin and another example of success. After less than a year of activity, SPEKTRUM, an open space that aims to link art and science, has already gathered a solid reputation in the field along with a trustee community of followers and participants. While we cross fingers for another year of funding for DNL, SPEKTRUM will continue to offer a rich program of concerts, performances, installations and debates.

Last Review – PORNTUBES: Reveals All @Disruption Network Lab, Berlin. By Pedro Marum, 2015

http://furtherfield.org/features/porntubes-reveals-all-disruption-network-lab-berlin

Featured image: Image from Joel Bakan: The Panopticon Power of the new media. Adbusters Jan 2012.

Marc Garrett and Ruth Catlow interview McKenzie Wark ahead of his keynote speech for Transmediale 2015 in Berlin this year.

It’s ten years since McKenzie Wark published his influential book, A Hacker Manifesto. Divided into 17 chapters, each offers a series of short, numbered paragraphs that mimic the epigrammatic style of Guy Debord’s The Society of the Spectacle. Wark then published, amongst others, a series of critically engaging books such as Gamer Theory and the Spectacle of Disintegration. Ruth Catlow and Marc Garrett from Furtherfield ask Wark how things have changed since these publications, focusing on how our everyday lives have been infiltrated by competitive game-like mechanisms that he described more than a decade ago.

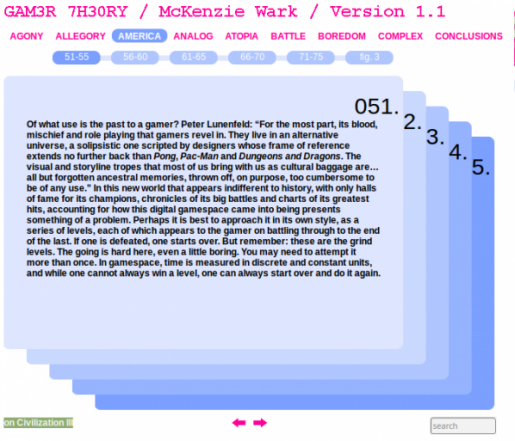

Furtherfield: You published the experimental writing project Gamer Theory first as a book in 2006 and then in 2007 with a specially revised 2.0 version online.

Mckenzie Wark: Yes, although I think the network book version is mostly broken now. Good thing there’s a dead-tree format back-up!

F: In it you argue that we’re living in a world that is increasingly game-like and competitive. Also that computer games develop a utopian version of the world that realizes the principles of the level playing field and reward based on merit; whereas in the world, this is promised, but rarely realized.

MW: Yes, I think one way of thinking about certain games is that they are a fully realized neo-liberal utopia, which actually gives them some critical leverage of everyday life, which is a sort of less-real, only partially realized version of this, where the playing field is not level, where the 1% get to ‘cheat’ and get away with it.

F: You also talk of the “enclosure of the world” within the “gamespace” where the logics of the game are applied as the general patterns of organization in the world. And this happens as we adapt to the allegorical forms of contemporary games media.

How do you think this situation has changed since you wrote Gamer Theory?

MW: Well, to me it looks like the tendency analyzed in Gamer Theory became even more the case. GamerGate looks among other things like a reactive movement among people who really want the neoliberal utopia in all its actual neofascist and misogynist glory to not be exposed as different to everyday life. When women gamers or game journalists stick their hands up and say, “hey, wait a minute”1, they just want to mow them down with their pixelated weapons. So the paradox is that as gamespace becomes more and more ubiquitous, the tension between promise and execution becomes ever more obvious.

F: Do you see the term Gamification that many theorists use currently as an elaboration of the ideas you developed in Gamer Theory? Or are there significant new ideas being explored?

MW: Ha! Well no, gamification was about celebrating the becoming game-like of everyday life. So I always saw that as a kind of regression from thinking about the phenomena to sort of cheerleading for it.

F: The software developer and software freedom activist Richard Stallman, when visiting Korea in June 2000 illustrated the meaning of the word ‘Hacker’ in a fun way. During a lunch with GNU fans a waitress placed 6 chopsticks in front of him. Of course he knew they were meant for three people but he found it amusing to find another way to use them. Stallman managed to use three in his right hand and then successfully pick up a piece of food placing it into in his mouth. Stallman’s story is a playful illustration of “hack value,” about changing the purpose of something and making it do something different to what it was originally designed to do, or changing the default.2

Stallman was highlighting fun and the mischievous imagination as part of the spirit of what he sees as hack value.

Where do you see lies the hack value in games culture? What has happened to the fun in games? Who’s having it and where is it happening?

MW: Stallman is one of the greats. Sometimes, people have this experience of scientific or technical culture as one of free collaboration, where there’s a real play of rivalry and recognition but based on producing and sharing knowledge as a kind of gift. JD Bernal had that experience in physics in the 30s and Stallman had, I think, a similar experience in computing. I think it’s important for those of us from the arts or humanities to honor that utopian and activist impulse coming out of more technical fields.

There’s a lively, critical and even avant-garde movement in games right now. That’s part of why it has provoked such a fierce reaction from a certain conservative corner. The culture wars are being fought out via games, which is as it should be, as it’s one of the dominant media forms of our times. So there’s certainly some sophisticated fun to be had alongside the more visceral pleasure of clearing levels.

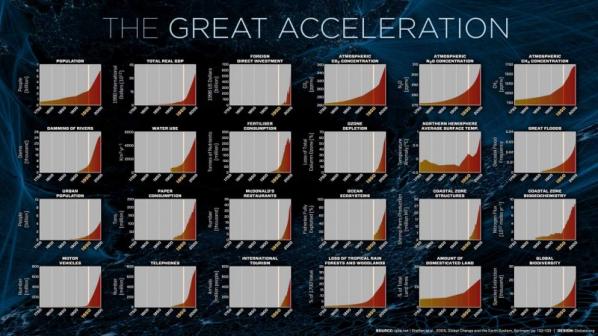

F: “Our species’ whole recorded history has taken place in the geological period called the Holocene – the brief interval stretching back 10,000 years. But our collective actions have brought us into uncharted territory. A growing number of scientists think we’ve entered a new geological epoch.”3 And, this new geological epoch has been proposed as – the Anthropocene.

In your essay ‘Critical Theory After the Anthropocene’4 you say “At a minimum, the Anthropocene calls on critical theory to entirely rethink its received ideas, its habituated traditions, its claims to authority. It needs to look back in its own archive for more useful critical tools.”

What are these ‘useful critical tools’ and how might theorists, new media artists, game designers and society at large put these to work?

MW: The ‘cene’ part of Anthropocene (from the Greek kainos) means a qualitative break in time. If time is in a sense always different, then kainos is the differently-different – a new kind of time. Those like Paul Crutzen who have advocated the use of the term Anthropocene to designate a new geological time have issued a major challenge as to how to interpret such a possibility. I leave it to the scientists to figure out if such a claim is scientifically valid. As someone trained in the humanities, I think the generous, comradely, cooperative thing to do is to try to interpret what our friends and colleagues in the sciences are telling us about the times. So in Molecular Red that was what I set out to do. Let’s take seriously the claim that these times are not ‘like’ other times. That I think calls for a rethinking of what from the cultural past might be useful now. I think we need new ancestors. Which is why, in Molecular Red, I went looking for them, based on the question: to which past comrades would the Anthropocene come as no surprise? I think Alexander Bogdanov, who understood a bit about the biosphere and the carbon cycle, would not be surprised. I think Andrey Platonov, who wrote about the attempts and failures to build a new kind of infrastructure for the Soviet experiment in a new mode of production would not be surprised. There are others, but those I thought were particularly helpful, not least because their Marxism remained in dialog with the sciences and technical arts. I don’t think the more romantic anti-science side of Western Marxism and continental thought is all that helpful at the moment, not least because it rules out of court exactly the kinds of scientific knowledges through which we know about the Anthropocene in the first place. The anti-science critique has been captured by the right, so we need new tactics.

F: Who’d be empowered by an encounter with your ideas and where do you see the potential for agency in the current economic and environmental contexts?

MW: Not for me to say really. Writers are usually the last people to have any clues as to what their writing says. There’s a sort of idiot quality to banging away on a keyboard. We’re word processors. Its always surprising to me the range of people who find something in what I write.

My hunch is that the future is in the hands of an alliance between those who make the forms and those who make the content: a hacker and worker alliance. It is clear that this civilization has already become unreal. Everyone knows it. We have to experiment now with what new forms might be.

F: And, where in the world do you see examples of individuals, groups and organizations, and or companies – who are putting into action some of the critical questions that you’re exploring in your writing?

MW: Besides Furtherfield? I never like to give examples. Everyone should be their own example. To détourn an old slogan of the 60s: be impossible, do the realistic!

F: In your later essay ‘The Drone of Minerva’5 you continue to write about the Anthropocene. But, you also bring to the table the subject of the Proletkult.6 The Proletkult aspired to radically modify existing artistic forms of revolutionary working class aesthetic which drew its inspiration from the construction of modern industrial society in Russia. At its peak in 1920, Proletkult had 84,000 members actively enrolled in about 300 local studios, clubs, and factory groups, with an additional 500,000 members participating in its activities on a more casual basis.

You are writing about the Proletkult in your latest book. Could you tell us a little something about this and how it will connect to contemporary lives?

MW: Proletkult was influential in Britain too, during the syndicalist phase of the British labor movement, up until the defeat of the 1926 general strike. After that the dominant forms were, on the one hand, the ethical-socialism and parliamentary path of the Labour Party, or the revolutionary Leninist party. Well, those paths have been defeated now too. I think we have to look at all of the past successes and failures all over again and cobble together new organizational and cultural forms, including a 21st century Proletkult.7 What that might mean is trying to self-organize in a comradely way to try and gain some collective charge of our everyday lives. It does not mean just celebrating actually existing working class cultures. Rather it’s more about starting there and developing culture and organization not as something reactive and marginalized but as something with organizational consistency and breadth. Since the ruling class clearly doesn’t give a fuck about us, let’s take charge of our own lives – together.

Thank you McKenzie Wark – Ruth Catlow & Marc Garrett 😉

Ruth Catlow will be at Transmediale 2015 CAPTURE ALL, moderating the keynote Capture All_Play with McKenzie Wark, on Sat, 31 Jan at 18:00.

Ruth is also participating in two other events, Play as a Commons: Practical Utopias & P2P Futures and The Post-Digital Review: Cultural Commons – http://www.transmediale.de/content/ruth-catlow

Die GstettenSaga: The Rise of Echsenfriedl review. SPOILER WARNING!

Johannes Grenzfurthner’s Post-Apocalyptic DIY Epic on Makers, Hacktivism and Media Culture.

“A mad post-collapse satire of information culture and tech fetishism, in a weird sort of melding of Stalker, Network, and The Bed-Sitting Room.” (Richard Kadrey)

Die GstettenSaga: The Rise of Echsenfriedl is an Austrian hackploitation art house film by Johannes Grenzfurthner, mastermind of the international art-technology-philosophy group monochrom, co-produced by the media collective Traum & Wahnsinn. Reimagining the makerspace as grindhouse, the story is set in the post-apocalyptic aftermath of the “Google Wars” – an armed global conflict between the last two remaining superpowers China and Google – which has turned what remained of the Alps into a Gstetten.

In Austrian German, “Gstetten” translates to wasteland, outback or ‘fourth world’ (Manuel Castells) and is a popular name for provincial towns – and sometimes just the less sophisticated parts of them. The area’s biggest semi-urban sprawl is Mega City Schwechat, the former home of Vienna International Airport, a refinery and a beer brewery. It is governed by the evil media mogul Thurnher von Pjölk (Martin Auer), a pretender who claims to be the inventor of key publishing technologies such as letterpress printing and rules the area with his tabloid newspaper. But the hegemony of his yellow press empire is contested by – spoiler alert! – makers, hackers and nerds, who are more leaning towards electronic media such as the recently rediscovered television. In order to get rid off this bothersome opposition, Pjölk devises an evil plan for wiping out Schwechat’s insubordinate creative class.

In an insidious political move, he pretends to reach out for the technophile faction by commissioning two of his reporters, the bootlicking opportunist Fratt Aigner (Lukas Tagwerker) and the brainy geek girl Alalia Grundschober (Sophia Grabner), to conduct an exclusive TV interview with the ultimate Gstetterati icon, the legendary innovator Echsenfriedl (“Lizard Freddy”) – on the basis of precarious employment conditions. The title character, who turns out to be an basilisk, embodies a mix of Steve Jobs, Richard Stallman and Julian Assange and lives in the depths of Niederpröll in his hideout much like Subcomandante Marcos – partly in order to protect the world from his killing gaze, which would, audio-visually transmitted, turn the whole of his fan base immediately to stone.

Grenzfurthner’s sci-fi-horror adaption of the Divine Comedy takes us on a retro-futuristic post-cyberpunk adventure in the tradition of cinema grotesque back to the dark days which preceded the Internet. The journey of our heroes – distinctively resembling Tarkovsky’s ‘stalkers’ – is a quest for extinct media technologies but their search for Echsenfriedl eventually leads the two protagonists to a deepened understanding of who they really are: the media industry’s precarious workforce under spectacular capitalism. While Fratt’s dirt track to enlightenment is paved with stumbling blocks, his brainy Beatrice advances with the determination of a Harawayian cyborg who makes use of her superior technical skills to save them from the zombified folk populating the Gstetten: uncanny creatures from the Kafkaesque bestiarium of Austria’s undead bureaucracy and its hanger-ons like armed-to-the-teeth Postal Service subcontractors (brilliant: monochrom’s Evelyn Fürlinger, also Grenzfurthner’s ex-wife) or the once powerful Farmers Association led by Jeff Ricketts (Firefly, Buffy the Vampire Slayer), who are worshipping antique pre-war EU funding applications as their sacred scriptures. Our friends receive the final hints for their search from the Sphinx Philine-Codec Comtesse de Cybersdorf (Eva-Christina Binder), a fantasy femme fatale who is torn between Plöjlk and Echsenfriedl, and the bearded drag queen Heinz Rand of Raiká (David Dempsey), an eccentric agricultural cooperative banker and possible descendant of Conchita Wurst.

The Gstettensaga’s fascinating cinematic pastiche is more than just a firework of rhizomatic intertextuality, a symptom of the depthlessness of postmodern aesthetics or excessive enthusiasm for experimentation in the field of form. In their infamous 1972 book Anti-Oedipus, Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari have identified the technique of bricolage as the characteristic mode of production under “schizophrenic” capitalism, a facet triumphantly magnified by the filmmakers. If every discourse is bricoleur, like Jacques Derrida suggested, suddenly ‘context’ can become the artist’s material or even a form of art in its own right:

“The more artists are consigned to an existence within a patchwork of niches, the more dependent they become on information resources, communication and networking. In this respect, aesthetic artefacts must take a stance toward a plethora or markedly heterogeneous contexts that sediment in one way or another: the conditions and circumstances surrounding their production, their various social fields from which (and for or against which) they speak: real or imagined audiences toward (or against) whose values a work, an approach or a position is targeted. This play with the factors affecting it and among which it must mediate has become an essential trait on an art form that might best be described as ‘Contextualism’.” [1]

What I found especially intriguing about the Gstettensaga is how the filmmakers responded to the various challenges of the feature film format by contextualising the whole production process, distribution, language adaptions (subtitles are an integral part of the story), soundtrack and even the viewing experience.

The film was initially commissioned by Austrian public broadcasting station ORF III as part of the series Artist-in-Residence for a budget of only €5000, set to be produced within a six months period. In response, monochrom used an embedded prank to raise money. The movie contains a text insert similar to watermarks used in festival viewing copies, which asks the viewer to report the film as copyright infringement by calling a premium-rate phone number (1.09 EUR/minute) and enabled Grenzfurthner to co-finance the film with proceeds from this new strategy he has named ‘crowdratting’. [2]

The Contextualist script – including outlines of scenes for improvisation – was written by Grenzfurthner and Roland Gratzer in just a couple of days in November 2013 in a Viennese restaurant. They also incorporated ideas that came up during their weekly meeting with the entire production crew, whereas some of the backstory was first created for monochrom’s pen-and-paper role-playing theatre performance Campaign. Principal photography – the camera work of Thomas Weilguny deserves the highest praise – commenced on December 2, 2013 and ended January 19, 2014, which left nearly 5 weeks for post-production and editing. Due to the fast production process and the financial limitations, no film score was composed for the Gstettensaga – instead, Grenzfurthner used an assortment of 8bit, synth pop and electronica tracks especially for their specific retro quality because “they may sound old-school to us, but not in the world of the Gstettensaga, where all retro electronic music is still impossible and futuristic.” [3]

The retro-futuristic world of Echsenfriedl is coming to a film festival, hacker con or Pirate Bay near you.

http://www.monochrom.at/gstettensaga/

Tamtam (Seara de proiectie la TT) / May 7, 2014 (Timisoara, Romania)

KOMM.ST Festival / May 11, 2014 (Anger, Austria)

Supermarkt (Dismalware) / June 7, 2014 (Berlin, Germany)

Fusion Festival / June 25-29, 2014 (Lärz Airfield, Mecklenburg, Germany)

Roswell International Sci Fi Film Festival / June 26-29, 2014 (Roswell, NM, USA)

iRRland movie night / June 30, 2014 (Munich, Germany)

qujochö Film Summer / July 3, 2014 (Linz, Austria)

HOPE X / July 18-20, 2014 (New York, New York, USA)

Fright Night Film Fest / August 1-3, 2014 (Louisville, KY, USA)

Gen Con Indy Film Festival 2014 / August 14-17, 2014 (Indianapolis, Indiana, USA)

San Francisco Global Movie Fest / August 15-17, 2014 (San Jose, CA, USA)

Rostfest / August 21-24, 2014 (Eisenerz, Austria)

Noisebridge / August 29, 2014 (San Francisco, USA)

/slash Filmfestival / September 18-28, 2014 (Vienna, Austria)

Simultan Fest / October 6-11, 2014 (Timisoara, Romania)

Phuture Fest / October 11, 2014 (Denver, Colorado, USA)

prol.kino / October 14, 2014 (Graz, Austria)

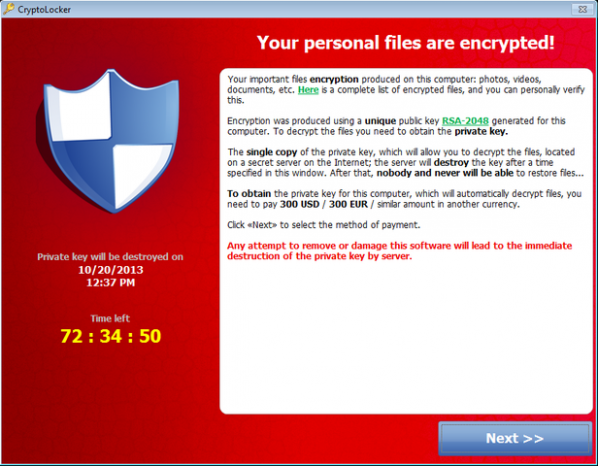

In “How Readers Will Discover Books In Future“, science fiction author Charles Stross envisions a future in which weaponized eBooks demand your attention by copying themselves onto your mobile devices, wiping out the competition, and locking up the user interface until you’ve read them.

This is only just science fiction. Even the earliest viruses often displayed messages and malware that denies access to your data until you pay to decrypt it already exist. ePub ebooks can execute arbitrary JavaScript, and PDF documents can execute arbitrary shell scripts. Compromised PDFs have been found in the wild. Stross’s weaponized ebooks are not more than one step ahead of this.

Why would eBooks want to act like that? To find readers. In the attention economy, the time required to read a book is a scarce resource. Most authors write because they want to be read and to find an audience. Stross’s proposal is just an extreme way of achieving this. In Stross’s scenario, authors are like the criminal gangs that use botnet malware to get your computer to pursue their ends rather than your own, use adware to coerce you into performing actions that you wouldn’t otherwise, or use phishing attacks to get scarce resources such as passwords or money from users.

As so much new art is made that even omnivorous promotional blogs like Contemporary Art Daily cannot keep up, scarcity of attention becomes a problem for art as well as for literature. And when people do visit shows they spend more time reading the placards than looking at the art. In these circumstances Stross’s strategies make sense for art as well. Particularly for net art and software art.

A net or software artwork that acted like Stross’s vampire eBooks would copy itself onto your system and refuse to unlock it until you have had time to fully experience it or have clicked all the way through it. It could do this in web browsers or virtual worlds as a scripting attack, on mobile devices as a malicious app, or on desktop systems as a classical virus.

Unique physical art also needs viewers. Malicious software can promote art, taking the place of private view invitation cards. Starting with mere botnet spam that advertises private views, more advanced attacks can refuse to unlock your mobile device until you post a picture of yourself at the show on Facebook (identifying this using machine vision and image classification algorithms), check in to the show on FourSquare, or give it a five star review along with a write-up that indicates that you have actually seen it. In the gallery, compromised Google Glass headsets or mobile phone handsets can make sure the audience know which artwork wants to be looked at by blocking out others or painting large arrows over them pointing in the right direction.

Net art can intrude more subtly into people’s experiences as aesthetic intervention agents. Adware can display art rather than commercials. Add-Art is a benevolent precursor to this. Email viruses and malicious browser extensions can intervene in the aesthetics of other media. They can turn text into Mezangelle, or glitch or otherwise transform images into a given style. In the early 1990s I wrote a PostScript virus that could (theoretically) copy itself onto printers and creatively corrupt vector art, but fortunately I didn’t have access to the Word BASIC manuals I needed to write a virus that would have deleted the word “postmodernism” from any documents it copied itself to.

Going further, network attacks themselves can be art. Art malware botnets can use properties of network topography and timing to construct artworks from the net and activity on it. There is a precursor to this in Etoy’s ToyWar (1999), or EDT’s “SWARM” (1998), a distributed denial of service (DDOS) attack presented as an artwork at Ars Electronica. My “sendvalues” (2011) is a network testing tool that could be misused, LOIC-style, to perform DDOS attacks that construct waves, shapes and bitmaps out of synchronized floods of network traffic. This kind of attack would attract and direct attention as art at Internet scale.

None of this would touch the art market directly. But a descendant of Caleb Larsen’s “A Tool To Deceive And Slaughter” (2012) that chooses a purchasor from known art dealers or returns itself to art auction houses then forces them to buy it using the techniques described above rather than offering itself for sale on eBay would be both a direct implementation of Stross’s ideas in the form of a unique physical artwork and something that would exist in direct relation to the artworld.

Using the art market itself rather than the Internet as the network to exploit makes for even more powerful art malware exploits. Aesthetic analytics of the kind practiced by Lev Manovich and already used to guide investment by Mutual Art can be combined with the techniques of stock market High Frequency Trading (HFT) to create new forms by intervening in and manipulating prices directly art sales and auctions. As with HFT, the activity of the software used to do this can create aesthetic forms within market activity itself, like those found by nanex. This can be used to build and destroy artistic reputations, to create aesthetic trends within the market, and to create art movements and canons. Saatchi automated. The aesthetics of this activity can then be sold back into the market as art in itself, creating further patterns.

The techniques suggested here are at the very least illegal and immoral, so it goes without saying that you shouldn’t attempt to implement any of them. But they are useful as unrealized artworks for guiding thought experiments. They are useful for reflecting on the challenges that art in and outside the artworld faces in the age of the attention-starved population of the pervasive Internet and of media and markets increasingly determined by algorithms. And they are a means of at least thinking through an ethic rather than just an aesthetic of market critique in digital art.

The text of this article is licenced under the Creative Commons BY-SA 4.0 Licence.

Featured image: Sam Meech, Punchcard Economy, 2013. Photo courtesy of FACT.

The new exhibition “Time & Motion” at FACT in Liverpool, UK, takes the pulse of punchcard protocol and creative capital in our own “Modern Times”.

The exhibition Time & Motion: Redefining Working Life at FACT Liverpool is a collaboration between FACT and the Creative Exchange at the Royal College of Art – an initiative which looks at how arts and humanities researchers can work with industry to effect digital innovation. Rachel Falconer reviews the exhibition in the context of the paradoxical dynamics of cognitive capital and the changing landscape of the labour market.

Now self-employed,

Concerned (but powerless),

An empowered and informed member of society

(Pragmatism not idealism),

Will not cry in public,

Less chance of illness,

Tires that grip in the wet

(Shot of baby strapped in back seat),

A good memory,

Still cries at a good film,

Still kisses with saliva,

No longer empty and frantic like a cat tied to a stick,

That’s driven into frozen winter shit

(The ability to laugh at weakness),

Calm,

Fitter,

Healthier and more productive

A pig in a cage on antibiotics.

Fitter Happier, Radiohead.

The frantic quest for the elusive Shangri-La of work/life balance is a neurotic luxury afforded only to the always-on, hyper-connected generation of precariously unstable home office workers[1] in our hypercapitalist society. The working rhythms of this emergent class of “precariat” [2] are far removed from the forensically prescribed scientific management resulting from the time and motion studies associated with Taylorism at the beginning of the last century. This shift in working patterns generated by the digital revolution is the primary focus of the exhibition Time and Motion, Redefining Working Life currently at FACT, Liverpool. From an archival, filmic view of the automated, (Western) industrial factory labourer to contemporary portraits of the global information worker’s state of perpetual imbalance and non-stop, hyper-connectedness [3] the participating artists expose the – often contradictory – ecologies of labour, consumption, and the conditions in which they operate. The exhibition also marks the collaboration between FACT and Creative Exchange at the Royal College of Art – an initiative which looks at how arts and humanities researchers can work with industry to effect digital innovation and confront contemporary modes of production.

Taking the archival stimulus of time and motion measurement as its title and industrial work patterns as a starting point, the exhibition Time & Motion is the latest in a series of exhibitions and symposia addressing immaterial labour and new working patterns in the age of globalisation and creative capital.[4] Rather than following the well-trodden path of casting the figure of the artist as digital labourer, or attempting to portray an expansive, post-colonial view of nomadic, labouring diasporas, Time and Motion reflects a more subversive and fragmented approach to the politics of work, rest and play in the global information economy.

Sam Meech’s Punchcard Economy is at once a homage to the textile industry and a recognition of the contemporary precariat. With more than a symbolic nod to northern England’s textile heritage, Punchcard Economy consists of a machine-knitted reinterpretation of the Robert Owen’s 8-8-8 ideal work/life balance.[5] The piece was produced on a domestic knitting machine using a combination of digital imaging tools and traditional punchcard systems. During a residency at FACT last year, Meech collected punchcards from visitors detailing their working hours. This data was then translated into a knitting pattern which was used to generate the final work – a banner depicting the contemporary working day. Any hours worked outside the eight-hour day appear as a glitch within the fabric. This banner – historically a symbol of the working class and trade unions – also denotes the fragmentation and blurring of national class structures in the era of globalisation.