Erica Scourti’s work addresses the mediation of personal and collective experience through language and technology in the net-worked regime of contemporary culture. Using autobiographical source material, as well as found text collected from the internet displaced into social space, her work explores communication, and particularly the mediated intimacy engendered by a digital paradigm.

The variable status and job of the artist is humorously fore-grounded in her work, assuming alternating between the role activist, ‘always-on’ freelancer, healer of social bonds and a self-obsessed documenter of quotidian experience.

Millions are blissfully unaware of the technological forces at work behind the scenes when we use social network platforms, mobile phones and search engines. The Web is bulging with information. What lies behind the content of the systems we use everyday are algorithms, designed to mine and sort through all the influx of diverse data. The byproduct of this mass online activity is described by marketing companies as data exhaust and seen as a deluge of passively produced data. All kinds of groups have vested interests in the collection and analysis of the this data quietly collected while users pursue their online activities and interests; with companies wanting to gain more insight into our web behaviours so that they can sell more products, government agencies observing attitudes around austerity cuts, and carrying out anti-terrorism surveillance.

Felix Stalder and Konrad Becker, editors of Deep Search: The Politics of Search Beyond Google,[1] ask whether our autonomies are at risk as we constantly adapt and tailor our interactions to the demands of surveillance and manipulation through social sorting. We consciously and unconsciously collide with the algorithm as it affects every field of human endeavour. Deep Search illuminates the politics and power play that surround the development and use of search engines.

But, what can we learn from other explorers and their own real-life adventures in a world where a battle of consciousness between human and machine is fought out daily?

Artist Erica Scourti spent months of her life in this hazy twilight zone. I was intrigued to know more about her strange adventure and the chronicling of a life within the ad-triggering keywords of the “free” Internet marketing economy.

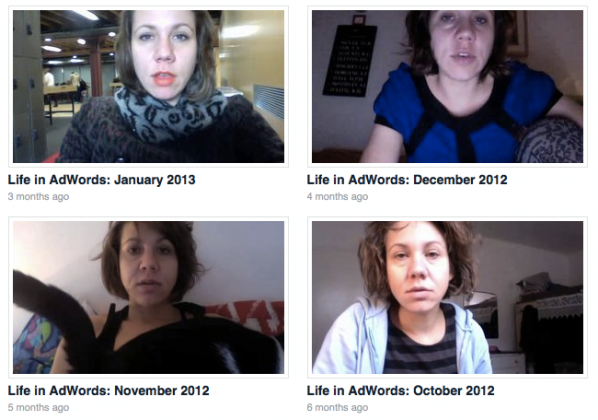

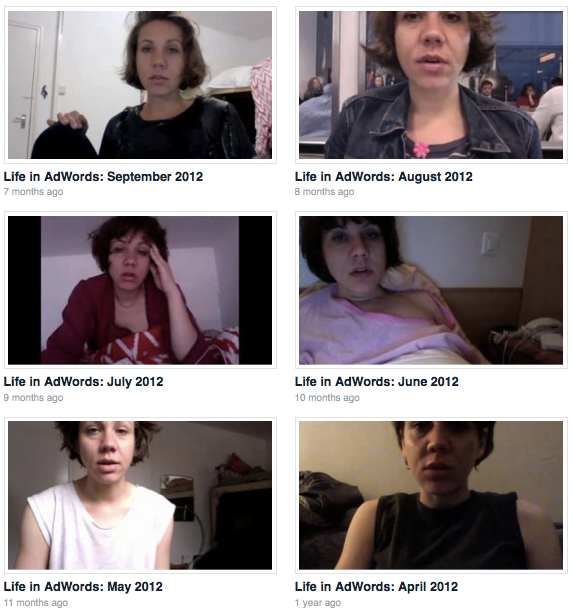

Marc Garrett: In March 2012, you began the long Internet based, networked art project called Life in AdWords, in which you wrote and emailed a daily diary to your Gmail account and performed regular webcams where you read out to the video lists suggested keywords. These links as you say are “clusters of relevant ads, making visible the way we and our personal information are the product in the ‘free’ Internet economy.”

Firstly, what were the reasons behind what seems to be a very demanding project?

Erica Scourti: Simply put, I wanted to make visible in a literal and banal way how algorithms are being deployed by Google to translate our personal information – in this case, the private correspondence of email content – into consumer profiles, which advertisers pay to access. It’s pretty widespread knowledge by now that this data ends up refining the profile marketers have of us, hence being able to target us more effectively and efficiently; just as in Carlotta Schoolman and Richard Serra’s 1973 video TV Delivers People,[2] which argues that the function of TV is to deliver viewers to advertisers, we could say the same about at least parts of the internet; we are the commodities delivered to the advertisers, which keep the Web 2.0 economy ‘free’. The self as commodity is foregrounded in this project, a notion eerily echoed by the authors who coined the term ‘experience economy’, who are now promoting the idea of the transformation economy in which, as they gleefully state, “the customer is the product!”, whose essential desire is to be changed. The notion of transformation and self-betterment, and how it relates to female experience especially within our networked paradigm is something I’m really interested in.

As Eli Pariser has pointed out with his notion of filter bubbles, the increasingly personalised web employs algorithms to invisibly edit what we see, so that our Google searches and Facebook news feeds reflect back what we are already interested in, creating a kind of solipsistic feedback loop. Life in AdWords plays on this solipsism, since it’s based on me talking to myself (writing a diary), then emailing it to myself and then repeating to the mirror-like webcam a Gmail version of me. This mirror-fascination also implies a highly narcissistic aspect, which echoes the preoccupation with self-performance that the social media stage seems to engender; but narcissism is also one of the accusations often leveled at women’s mediated self-presentation in particular, despite, as Sarah Gram notes in a great piece on the selfie, [3] it being nothing less than what capital requires of them.

![Girl with a Pearl Earring and a Silver Camera. Digital mashup after Johannes Vermeer, attributed to Mitchell Grafton. c.2012. [4]](http://www.furtherfield.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/vermeer_selfie.jpg)

And as this project is a form of autobiography and diary-writing, it could also be seen as both narcissistic and as asserting the importance of personal experience and emotions in the construction of a humanist, unified subject. Instead, I wanted to experiment with a way of writing a life story that operated somewhere between software and self, so that, as Donna Harraway says “it is not clear who makes and who is made in the relation between human and machine”. Part of the humour of the project arises from the dissonance between the staged realism of the webcam (and my real cat/ hangover/ bad hair) with the syntactically awkward, machinic language, which undermines any notion that this diary is the expression of any authentic subject.

The demanding aspect of it is something I was interested in too, since it calls up the notion of endurance as a virtue, and therefore as a value-enhancer, which many artworks – from mind-boggingly labour intensive supercut-style videos to sculptures made from millions of pins (or whatever) – trade on. You just can’t help but ask ‘wow…how long did that take?!’ – as if the time, labour and effort, i.e. the endurance, necessarily confer value. So there is a parallel between a certain kind of ‘age of austerity’ rhetoric that valorises resilience and endurance and artworks that trade on a similar kind of doggedness – like Life in AdWords does.

And finally – it made me laugh. Some of the text was so dumb, and funny, it amused me to think of these algorithms dutifully labouring away to come up with key-phrases like ‘Yo Mamma jokes’ and ‘weird pants’.

MG: It ran until 20th January 2013, and ended due to system changes in the Gmail ad settings. How many videos did you produce and were you glad when it all had finally ended?

ES: Not sure how many I made – but I was 6 weeks short of the intended year, so definitely over 300. Actually I was infuriated and somewhat depressed when it ended without warning and in a moment of panic I even thought about somehow cheating it out to the end; but working with a system that is beyond your control (i.e. Google) necessarily involves handing over some of your authorial agency. So instead I embraced the unexpected ending and threw a kind of send-off party plus performance in my bedroom/ studio to mark it.

But this question of agency is obviously crucial in the discussion of technology and runs through the project in various ways, beyond its unintended termination. At the level of the overall structure, it involves following a simple instruction (to write and process the diaries every day and do the webcam recording) which could be seen as the enactment of a procedure that echoes the operation of a software program carrying out automated scripts. And on the level of the texts, while all the language used in the project was generated and created by the software, I also was exercising a certain amount of control over which sections of the diary I favoured and editing the resulting lists, a move which seemingly reasserts my own authorial agency.

Thus the texts are more composed and manipulated than they first appear, but of course the viewer has no way of knowing what was edited out and why; they have to take it on faith that the texts they hear are the ‘real’ ones for that diary.

MG: During this period you recorded daily interactions of the ongoing experience onto webcam. As you went through the process of viewing the constant Google algorithms, I am wondering what kind of effect it had on your state of mind as you directly experienced thousands of different brands being promoted whilst handing over the content once again, verbally to the live camera?

ES: I’m not sure what effect it had on my state of mind, though considering the amount of concerned friends that got in touch after viewing the videos, Google certainly thought I was mostly stressed, anxious and depressed. Maybe it’s just easier to market things to a negative mind state.

But also, the recurrence of these terms was no coincidence; early film theorist Tom Gunning has argued that Charlie Chaplin’s bodily movement in Modern Times [5] ‘makes it clear that the modern body is one subject to nervous breakdown when the efficiency demanded of it fails,’ and compares his jerky, mechanical gestures with the machines of his era.

So I was interested in if and how you could do something similar for the contemporary body; how can we envisage it and its efficiency failures in relation to the technology of today when our machines are opaque and unreadable, if we can see them at all. Maybe what they ‘look like’ is code (a type of language), so it would entail some kind of breakdown communicated through language rather than bodily gestures – though the deadpan delivery certainly evokes a machinic ‘computer says no’ type of affectlessness.

Also, Franco Berardi has spoken of the super-speedy fatigued denizen of today’s infoworld, for whom “acceleration is the beginning of panic and panic is the beginning of depression”. In a sense this recurrent theme of stress and anxiety disavows the idea of the efficient, ever-ready, always-on subject of neo-liberalism – and yet the project as a whole kind of sneakily joins the club too, since it obeys the imperative of productivity by turning a diary (personal life, non-work) into a ‘project’ (i.e. work).

As mentioned earlier in terms of the ‘transformation economy’, I’m really interested in this idea of efficiency also as it manifests in rhetorics of self-betterment, and its relation to the neo-liberal promotion of self-responsibility (if you’re poor, it’s your fault….). Diaries and journal writing – as well as meditation, yoga, therapy, self-help etc – are often championed in everything from cognitive fitness to management literature as excellent ways of becoming more ‘efficient’. The underlying belief seems to be that by unloading all the crap that weighs you down, from emotional blockages to unhelpful romantic attachments to an overly-busy mind, you’d get an ‘optimised you’. Why this is necessarily a good thing – apart from the elusive promise of ‘happiness’ of course – is never really discussed.

Tiqquun’s notion of the Young Girl, the model consumer-citizen, is interesting in this regard – taking good care of oneself reframed as a form of subservience which maintains the value and usefulness of our bodies and minds to capital. Their idea that the Young Girl (not actually a gendered concept in their estimation) “advances like a living engine, directed by, and directing herself toward the Spectacle” also points to the irony beneath what appears to be a very humanist/ individualist inflection to these discourses of self-realisation: they could also be read as a latent desire to become somehow more ‘machine-like’, as if we could therapise/ meditate/ journal/ jog away our mind-junk with the swiftness and ease of emptying the computer’s trash, thereby becoming more productive.

And yet I’m clearly complicit in this, as I write diaries, meditate, do yoga and obsess over my bad time management, as Life in AdWords makes clear both in the recurrence of all these activities in the texts and obviously in its structure as a daily journal project.

MG: Robert Jackson in his article Algorithms and Control discusses in his conclusion that even though “use of dominant representations to control and exploit the energies of a population is, of course, nothing new”, when masses of people respond and say yes to this “particular reduced/reductive version of reality”, as an act of investment it “is the first step in a loss of autonomy and an abdication of what I would posit is a human obligation to retain a higher degree of idiosyncratic self-developed world-view.” Alex Galloway also explores this issue in his book Protocol: How Control Exists after Decentralization, where he argues that the Internet is riddled with controls and that what Foucault termed as “political technologies” as well as his concepts around biopower and biopolitics are significant.

Life in AdWords, seems to express the above contexts with a personal approach on the matter. Drawing upon an artistic narrative as the audience views your gradual decline into boredom and feelings of banality. The viewer can relate to these conditions and perhaps ask themselves similar questions as they go through the similar experiences. Thus, through performance and a play on personal sacrifice on a human level, it elucidates the frustrations on the constant, noise and domination of these protocols and algorithms and how they may effect our behaviours.

With this in mind, what have you learnt from your own experience, and how do you see others regaining some form of conscious independence from this state of sublimation?

ES: I found Galloways’ explanation of Foucault’s notions of biopower to be some of the most interesting parts of that book – as he puts it “demographics and user statistics are more important than real names and real identities”, so it’s not ‘you’ according to your Amazon purchase history, but more ‘you’ according to Amazon’s ‘suggestions’ (often scarily accurate in my experience). Which is where the algorithms come in; they do the number-crunching to be able to predict what you might buy, and hence who you are, not because anyone cares about you particularly, but because where you fit in a demographic (a person who is interested in art, technology, etc..) is useful information and creates new possibilities for control.

Regaining conscious independence… hmm. I found it interesting that during the project, the people I explained it to would often report back to me on what keywords their emails had produced, and what adverts came up on Facebook, as they hadn’t really noticed before – so perhaps in these cases it made people more conscious of the exchange taking place in the ‘free’ web economy. Others took up AdBlocker in response, which is one way of gaining distance – by opting out. However, the info each of us generates is still useful, since even if you aren’t seeing the ads, your choices and interactions are still being parsed and thus help delineate a particular user group of citizen-consumers.

Despite this, my feeling is that opting out – if it’s even possible – can be a way of pretending none of this stuff is happening. I’m generally more interested in finding ways of working with the logic of the system, in this case the use of algorithms to sell things back to us, and making it overly obvious or visible. Geert Lovink asked whether its possible for artists to adopt an “amoral position and see control as an environment one can navigate through instead of merely condemn it as a tool in the hands of authorities” and his suggestion of using Google to do the ‘work’ of dissemination for you, in spreading your meme/ word/ image, is one I’ve thought about, particularly in other works (especially Woman Nature Alone). This approach entails hijacking the process by which Google’s algorithms organise the hierarchy of visibility to one’s own ends – a ‘natural language’ hack, as Lovink puts it.

In contrast, Life in AdWords makes visible the working of the algorithmic system more on the level of the language it produces. It also employs humour, and laughter has been one of the main responses people have had when watching the videos, for a number of reasons. The frequent dumbness of the language and/ or the juxtapositions (‘Where is God?’, ‘Eating Disorder Program’); the flattening out of all difference between objects/ feelings/ places (e.g. work-related stress, cat food, God, Krakow); and the lack of shame the software exhibits in enumerating bodily and mental malfunctions (blood in poop, wet bed, fear of vomiting) are all quite amusing in and of themselves.

That shameless aspect also echoes the over-sharing and ‘too much information’ tendencies the web (especially social media) seems to encourage, which Rob Horning has written about in his excellent blog, Marginal Utility. It also foregrounds that whatever the algorithms can do, what they still can’t do is emulate the codes of behaviour governing human interaction – including knowing when to shut up about your ‘issues’.

The frequent allusions to these bodily and mental blockages also point to the limits of the productivity imperative – a refusal to perform enacted through minor breakdowns – while bringing it back to an embodied subject, who despite her immersion in networked space is still a body with messy, inefficient feelings, needs and urges. And the comically limited portrait the keywords paint maybe suggests that despite the best efforts of Web 2.0 companies, we still are not quite reducible to a list of consumer preferences and lifestyles.

MG: What are you up to at the monment?

ES: Amongst other things I’m doing a residency with Field Broadcast (artists Rebecca Birch and Rob Smith) called Domestic Pursuits, a project which ‘considers the domestic contexts of broadcast reception and the infrastructure that enables its transmission.’

And I’m working on some drawings plus a video involving Skype meditation with members of the Insight Timer meditation app community, for A Small Hiccup, curated by George Vasey and opening 24th May at Grand Union, Birmingham- the video is being shown online tommorrow.

Also I’m attempting and mostly failing at the moment to write my dissertation for the MRes in Moving Image Art I’m doing at Central St Martins and LUX.

Personal Web searching in the age of semantic capitalism: Diagnosing the mechanisms of personalisation. Martin Feuz, Matthew Fuller, and Felix Stalder.

http://firstmonday.org/article/view/3344/2766

Live Performance. KONRAD BECKER (aka Monoton) featuring SELA 3 themes from “OPERATIONS” (15 min.). Published on Jul 9, 2012. YouTube.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HMscYTAF4wY

Erica Scourti was born in Athens, Greece in 1980 and now lives in London. After a year studying Chemistry at UCL, an art and fashion foundation and a year of Fine Art Textiles at Goldsmiths, she completed her BA in Fine Art at Middlesex University in 2003 and is currently enrolled on a Research degree (Masters) in Moving Image Art at Central Saint Martin’s College of Art & Design, run in conjunction with LUX. Her area of research is the figure of the female fool in performative video works.

She works with video, drawing and text, and her work has been screened internationally at museums like the Museo Reine Sofia, Kunstmuseum Bonn and Jeu de Paume Museum, as well as festivals such as the Recontres Internationales, interfilm Berlin, ZEBRA Film Festival, Antimatter, Impakt, MediaArt Friesland, 700IS as well as extensively in the UK, where she won Best Video at Radical Reels Film Competition; recent screenings include Video Salon Art Prize, Exeter Phoenix, Bureau Gallery, Tyneside Cinema and Sheffield Fringe Festival.

Her work has also been published in anthologies of moving image work like Best of Purescreen (vols 1, 2 and 3) and The Centre of Attention Biannual magazine.

more info – http://www.ericascourti.com/art_pages/biography.html