Lately, I have noticed in myself a tendency to sign up for events which reveal little of what to expect beforehand. This leads to a heady mix of anticipation and mild terror. Dark Days, the brainchild of Ellie Harrison fitted that description, although I felt that at 16hrs long, it was a mere blip on my riskometer, compared to week-long excursions I’ve previously taken into the unknown. In short, I would be spending the night in Glasgow’s Gallery of Modern Art (GoMA), in a pop-up community of 99 strangers, contemplating how we might manage to live together (put up with each other) in a future where buildings might need to be used in ways which serve the needs of the population better…Count me in!

The camp manual gave thorough and due attention to health & safety issues like pyjamas and woollen blankets, but scant reassurance on how the experiment would avoid a rapid descent into anarchy. In the absence of concrete information, my mind ran amok. I therefore decided, that on arrival we would be immersed in an imagined scenario where all manner of crises has befallen our village, that it would be up to us to work out how we would rebuild society. This would be a tense, high adrenaline experience involving sleep deprivation, maybe starvation, and intractable social issues, to be debated until we all came to a common vision. We might never make it out of there.

As it turned out, Dark Days was none of those things; it was a whole lot more. On arrival in Glasgow, I succumbed to mild panic and bought myself a sleeping pad, twinpack of nougat caramel chocolate, and a bottle of fizzy pop (in direct contravention of the bring a bottle of water mandate), to supplement the food I already had in my rucksack. Provisions bolstered, I relaxed & enjoyed my pilgrimage to GoMA; I felt carefree, adventurous and rebellious; none of the strangers walking beside me had a clue what I was about to do. I felt dangerous and daring.

I joined the short queue outside GoMA, exchanging nervous banter with fellow participants (“Is this where the over-excited and slightly nervous should queue for the coming apocalypse?”). We eyed each other up, I began to relax. We all looked pretty ‘normal and balanced’ individuals. Who could predict what would surface once the pressure was on, though? A child walking past was overheard saying “you’re the worst Mum ever”. He was joking of course, or was he? Was society breaking down already? When the doors opened, we edged inside, one and two at a time. We were subjected to challenging initiative tests – first to register with the clipboard on the right if your surname is A-L. I was standing on the left, I dithered. My surname begins with a ‘G’. My faculties were already leaving me. Through the archway to the welcome desk, I shuffled forward and joined the queue on the right. More nervous exchanges. The queue on the left was faster, we silently wondered whether it would be impolite to skip over to the other line. No one moved. A couple of minutes later, I spotted a notice ‘A-L’ taped to the left side of the desk. A dastardly ploy! Somewhere, a hidden camera would be watching me, a witness to my ineptitude. This was before the evening had even begun. My nerves jangled. Beyond the mysterious white cube that had blocked our view of the great hall (was that where the mind games would take place?), we placed our belongings around the edges and sat in the large circle of chairs which awaited. More nervous chatter, it was clear that no one had the faintest notion what the night would hold. I was reassured. Speakers, microphones and video cameras (with red light already flashing) were dotted around the space, we did our best to ignore them. There will be screenings in March in Glasgow, and the film will be made available online #ohdear. Someone noticed that there were not enough chairs for all members of the community to have a seat. 20ish people stood, or sat on the floor. Was this a lack of resources on GoMA’s part, or was it intentional? Time would tell.

An entertaining and enlightening journey followed, into the challenges of consensus decision making, based around the formation of ‘affinity groups’. The groups were determined by allowing anyone who felt brave enough to make suggestions of how we might spend our time together, members of the community chose which group they wanted to join. The options were many and varied; building a Tower of Awesome; a general knowledge quiz; game playing; climate change discussion group; music & dance; a group with no plan; a manifesto writing group; a skills sharing group and a community focused ‘hub’ group. This was the fascinating moment for me, as my intended plan for the evening was abandoned. Along with my keen interest in community building, I was at GoMA to write poetry, to create a distillation of the night’s happenings for future posterity. Logic would dictate that I should go where the most words would be; but I was filled with an irresistible urge to play games. I had already co-dreamed an impressive list of sleeping bag related games with the person sitting to my left (slug, husky races, who can wear the most sleeping bags, sack races to name a few).

We gathered in our groups to discuss what we would do, what we would need, what format the evening should take and (as it turns out, crucially) what time we would like the lights to go out. A spokesperson was selected to represent each group on a ‘spokescouncil’, where the representatives would reach a consensus on the issues of how the evening would go, any conflicts over resources and at what time the lights should go out. The facilitators did a magnificently heroic job of keeping the discussions focused; ‘brief’ overviews spiralled out of control, the facilitator gently herded the kittens. “I’ll say again: Each spokesperson is to give a brief outline of what their group will do tonight” quickly became “Each person has 30 seconds to tell us”. Those not on the spokescouncil chortled and tried to stifle the mounting hysteria. The only spokesperson not tempted to flout the guidance was from the ‘no plan’ group, because well, they had ‘no plan’. It became clear that with the proposed ‘Tower of Awesome’ and sub-idea of sleeping bag fort, that chairs were the key resource to be negotiated. Turning out the lights also became a decision to be much wrangled over; there were lots of needs, ranging from ‘pretty much now’ to ‘what the hell, let’s stay up all night’.

Negotiations were funny, tense, agonising and did I mention funny? At one point, I was weeping with laughter; we were tantalisingly close to reaching consensus when out of leftfield came a demand for an opening ceremony. Fine we all said, have your opening ceremony, let’s just get this done. The sage advice of the facilitators was beginning to hit home – only use consensus decision making for important decisions and ask yourself ‘do I want to spend all night making decisions, or do I want to have some fun?’. By now it was heading towards 11pm, and there were games waiting to be played. We were close. We were restless. The facilitator then fulfilled the most crucial obligation of consensus decision making, and asked the spokescouncil whether there were any objections. We held our breath, pleading inwardly for no one to speak up. Come on spokescouncil, you could do it! Hands went up. Sigh. 15mins of jaw-clenching tension followed, as the universal ‘need to be heard’ surfaced in a few last desperate arm waves; “Well, this isn’t exactly an objection, but I’d just like to say…”. “Any final objections?” our facilitator said, possibly through gritted teeth. Silence. We breathed a collective sigh of relief. “I think we have a consensus”. We cheered. Let the games begin.

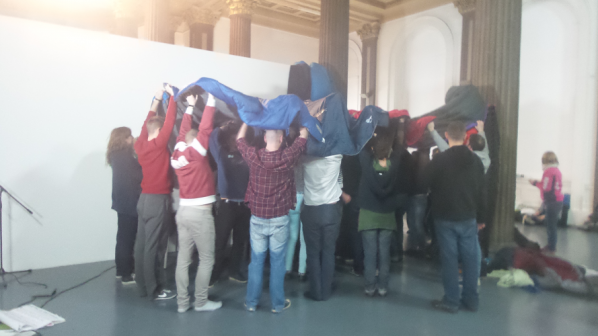

The opening ceremony was a resounding success, as we all ‘became the chairs’ in a self-supporting and poignant human chair circle. Next, we lined up in small groups, ran the length of the gallery, and then turned and felt the breeze on our faces. It was magical. We smiled broad smiles, laughed, and revelled in a joyful camaraderie for the rest of the night. How could anyone think of going to sleep when there was crowdsurfing to be done, wink murder to be played (epic) and thigh drumming to be learned? It was a fascinating experience. I observed an interesting phenomenon; each time an activity gained a certain number of people, others noticed and ran to join. The wink murder circle doubled in size while the detective was behind a column and the silent disco grew within minutes, without a word being spoken. We generally didn’t stay segregated in our own groups, we welcomed others in unreservedly, and joined other groups when the mood took us. We were a model society, just for one night. We self-organised, and ensured that there were enough chairs to meet the needs of towers, forts, hubs and deep discussions. It was beautiful and inspiring. It was epic and poetic. We had survived. No, we had flourished.

Extract from my #DarkDays poem:

Dissent can be difficult,

blocks disrupt.

Build a safe environment

for breaking power,

freefall into your position,

annex yourself from your ideas;

interrupt silence,

with or without permission,

be the instigator of your rebellion.

Move the chairs

Wind-down at 2am came all too soon, and we made ourselves cosy for the night. My mind was skipping and crowdsurfing, and reliving dramatic wink murder deaths; how on earth was I going to sleep?? I didn’t. Well, maybe an hour or so. I lay under my blanket (not woollen) and listened to the rise and fall of contented breathing, with the occasional soft, acoustically augmented, echo-y snoring (cautionary note; snorers should choose their sleeping spot carefully). I contemplated how different the experience might have been in the ‘real world’, where people wouldn’t be so accommodating, wouldn’t be on their best behaviour. I suspect there might have been less laughter and fewer games, certainly no Tower of Awesome or sleeping bag fort. Time will tell.

There is a distinct buzz that goes with embracing the opportunity to stay in a public building overnight, I encourage everyone reading this to add such an experience to their bucket list. You might have to go to some lengths, might have to personally orchestrate an event, in order to create your opportunity. Whatever it takes, it will be worth it. I promise. Think ‘Night in the Museum’, meets giant slumber party, with midnight feast thrown in, but with no adults to tell you what you can and can’t do. We were the adults, we made our own rules. Even when a camper was scaling internal walls in the importance of building the most spectacular sleeping bag fort ever seen, no one came to tell us to stop. We all learned something valuable from that endeavour; the fort was unbearably hot inside, so could only be tolerated for short periods of time. Next time – ventilation. One participant put our limited imaginations to shame, by bringing a hammock to sleep in. We all wanted to be that guy. We ate chocolate and muffins for breakfast.

All of your dreams for a different world, made real in one spectacular night in a museum, art gallery, library, school or conference room (the possibilities are endless). Life will never be the same again, you will be changed, and you will want to do it again and again.

Note from reviewer: Names have been omitted in order to protect the subversive, the wall-scaling, the almost-pyjama-wearing, the non-sleeping campers.

For over 17 years, Furtherfield has been working in practices that bridge arts, technology, and social change. Over these years, we have been involved in many great projects and collaborated with and supported various talented people. Our artistic endeavours include net art, media art, hacking, art activism, hacktivism and co-curating. We have always believed it is essential that the individuals at the heart of Furtherfield practice in arts and technology and are engaged in critical enquiry. For us, art is not just about running a gallery or critiquing art for art’s sake. The meaning of art is in perpetual flux, and we examine its changing relationship with the human condition. Furtherfield’s role and direction as an arts collective is shaped by the affinities we identify among diverse independent thinkers, individuals and groups who have questions to ask in their work about the culture.

Here I present a selection of Furtherfield projects and exhibitions featured in the public gallery space we have run in Finsbury Park in North London for the last two years. I set out some landmarks on the journey we have experienced with others and end my presentation with news of another recently opened space (also in the park) called the Furtherfield Commons.

Running themes in this presentation include how Furtherfield has lived through and actively challenged the disruptions of neoliberalism. The original title for this presentation was ‘Artistic Survival in the 21st Century in the Age of Neoliberalism’. The intention was to stress the importance of active and open discussion about the contemporary context with others. The spectre of neoliberalism has paralleled Furtherfield’s existence, affecting the social conditions, ideas and intentions that shape the context of our work: collaborators, community and audience. Its effects act directly upon ourselves as individuals and around us: economically, culturally, politically, locally, nationally and globally. Neoliberalism’s panoptic encroachment on everyday life has informed Furtherfield’s motives and strategies.

In contrast with most galleries and institutions that engage with art, we have stayed alert to its influence as part of a shared dialogue. The patriarch, neoliberalism, de-regulated market systems, corporate corruption and bad government; each implement the circumstances where we, everyday people, are only useful as material to be colonized. This makes us all indigenous peoples struggle under the might of the wealthy few. Hacking around and through this impasse is essential if we maintain human integrity and control over our social contexts and ultimately survive as a species.

“The insights of American anarchist ecologist Murray Bookchin into environmental crisis hinge on a social conception of ecology that problematises the role of domination in culture. His ideas become increasingly relevant to those working with digital technologies in the post-industrial information age, as big business develops new tools and techniques to exploit our sociality across high-speed networks (digital and physical). According to Bookchin, our fragile ecological state is bound up with a social pathology. Hierarchical systems and class relationships so thoroughly permeate contemporary human society that the idea of dominating the environment (to extract natural resources or to minimise disruption to our daily schedules of work and leisure) seems perfectly natural despite the catastrophic consequences for future life on earth (Bookchin 1991). Strategies for economic, technical and social innovation that focus on establishing ever more efficient and productive systems of control and growth, deployed by fewer, more centralised agents, have been shown to be both unjust and environmentally unsustainable (Jackson 2009). Humanity needs new social and material renewal strategies to develop more diverse and lively ecologies of ideas, occupations and values.” [1] (Catlow 2012)

It is no longer critical, innovative, experimental, avant-garde, visionary, evolutionary, or imaginative to ignore these large issues of the day. Suppose we, as an arts organization, shy away from what other people are experiencing in their daily lives and do not examine, represent and respect their stories. In that case, we rightly should be considered part of an irrelevant elite and seen as saying nothing to most people. Thankfully, many artists and thinkers take on these human themes in their work in various ways, on the Internet and in physical spaces. So much so, this has introduced a dilemma for the mainstream art world regarding its relevance and whether it is contemporary.

Furtherfield has experienced, in recent years, a large-scale shift of direction in art across the board. And this shift has been ignored (until recently) by mainstream art culture within its official frameworks. However, we need not only to thank the artists, critical thinkers, hackers and independent groups like ours for making these cultural changes, although all have played a big role. It is also due to an audience hungry for art that reflects and incorporates their social contexts, questions, dialogues, thoughts and experiences. This presentation provides evidence of this change in art culture, and its insights flow from the fact that we have been part of its materialization. This is grounded knowledge based on real experience. Whether it is a singular movement or multifarious is not necessarily important. But, what is important is that these artistic and cultural shifts are bigger than mainstream art culture’s controlling power systems. This is only the beginning, and it will not go away. It is an extraordinary swing of consciousness in art practice forging other ways of seeing, being, thinking, making and becoming.

Furtherfield is proud to have stuck with this experimental and visionary culture of diversity and multiplicity. We have learned much by tuning into this wild, independent and continuously transformative world. On top of this, new tendencies are coming to the fore, such as re-evaluations and ideas examining a critical subjectivity that echo what Donna Haraway proposed as ‘Situated Knowledge’ and what the Vienna-based art’s collective Monochrom call ‘Context Hacking’. Like the DADA and the Situationist artists did in their time, many artists today are re-examining current states of agency beyond the usually well-promoted, proprietorial art brands, controlling hegemonies and dominating mainstream art systems.

Most Art Says Nothing To Most People.

“The more our physical and online experiences and spaces are occupied by the state and corporations rather than people’s own rooted needs, the more we become tied up in situations that reflect officially prescribed contexts, and not our own.” [2]

To start things off, I want to refer to a past work that Heath Bunting (co-founder of irational.org) and I were involved with in 1991. The above image is a large paste-up displayed on billboards around Bristol in the UK. At the time, as well as being part of other street art projects, pirate radio and BBS boards, Heath and I and others were members of the art activist collective Advertising Art. The street art we made critiqued presumed ownership of art culture by the dominating elites. The words “Most Art Says Nothing To Most People” have remained an inner mantra ever since.

Furtherfield is inspired by ideas that reach for a grassroots form of enlightenment and nurture progressive ideas and practices of social and cultural emancipation. The Oxford English Dictionary describes Emancipation as “the fact or process of being set free from legal, social, or political restrictions; liberation: the social and political emancipation of women and the freeing of someone from slavery.”

“Kant thought that Enlightenment only becomes possible when we are able to reason and to communicate outside of the confines of private institutions, including the state.” [3] (Hind 2010)

Well, a start would be getting organised and building something valuable with others.

As usual, it is up to those people who know that something is not working and those feeling the brunt of the issues affecting them who end up trying to change the conditions. It is unlikely that this pattern of behaviour will change.

To expect or even wish those who rule and those serving them to change, challenge their behaviours and seriously critique their actions is as likely as winning the National Lottery, perhaps even less.

Art critic Julian Stallabrass proposes that there needs to be an analysis of the operation of the art world and its relation to neoliberalism. [4]

In the above publication, Gregory Sholette argues “that imagination and creativity in the art world thrives in the non-commercial sector, shut off from prestigious galleries and champagne receptions. This broader creative culture feeds the mainstream with new forms and styles that can be commodified and utilized to sustain the few elite artists admitted into the elite. […] Art is big business: a few artists command huge sums of money, and the vast majority are ignored, yet these marginalized artists remain essential to the mainstream cultural economy serving as its missing creative mass. At the same time, a rising sense of oppositional agency is developing within these invisible folds of cultural productivity. Selectively surveying structures of visibility and invisibility, resentment and resistance […] when the excluded are made visible when they demand visibility, it is always ultimately a matter of politics and rethinking history.” [5] (Sholette 2013)

Drawing upon Sholette’s inspirational, unambiguous and comprehensive critique of mainstream art culture in the US. I want to consider examples closer to home blocking artistic and social emancipation avenues that also need an urgent critique. And this blockage resides within media art culture (or whatever we call it now) itself. Recently, I read a paper about ‘Post-Media’ – said to “unleash new forms of collective expression and experience” [6]- which featured in its text-only established names. Furtherfield is native to ‘Post-Media’ processes, a concept that theorists in media art culture are just beginning to grasp. This is because they tend to rely on particular theoretical canons and the defaults of institutional hierarchies to validate their concepts. Also, most of the work they include in their research is shown in established institutions and conferences. They assume that because a particular artwork or practice is accepted within the curatorial remits of a conference theme, the art shown represents what is happening, thus more valid than other works and groups not included. This is a big mistake. It only reinforces the conditions of a systemic, institutionalised, privileged elite and enforces a hierarchy that will reinforce the same myopic syndromes of mainstream art culture. The extra irony here is that many supposedly insightful art historians and theorists advocate a decentralised, networked culture in their writings or as a relational context. However, many do not support or create alternative structures with others. The real problem is how they acquire their knowledge. Presently the insular and hermetically sealed dialectical restraints and continual reliance on central hubs as official reference is distancing them from the actual culture they propose to be part of.

“We must allow all human creativity to be as free as free software” [7] (Steiner, 2008)

Furtherfield comes from a cultural hacking background and has incorporated into its practice ideas of hacking not only with technology but also in everyday life. Furtherfield is one big social hack. Hack Value advocates an art practice and cultural agency where the art includes the mechanics of society as part of its medium and social contexts with deeper resonances and a critical look at the (art) systems in place. It disrupts and discovers fresh ways of looking and thinking about art, life and being. Reclaiming artistic and human contexts beyond the conditions controlled by elites.

Hack Value can be a playful disruption. It is also maintenance for the imagination, a call for a sense of wonder beyond the tedium of living in a consumer, dominated culture. It examines crossovers between different fields and practices concerning their achievements and approaches in hacking rather than as specific genres. Some are political, and some are participatory. This includes works that use digital networks, physical environments, and printed matter. What binds these examples together is not only the adventures they initiate when experimenting with other ways of seeing, being and thinking. They also share common intentions to loosen the restrictions, distractions and interactions dominating the cultural interfaces, facades and structures in our everyday surroundings. This relates to our relationship with food, tourism, museums, galleries, our dealings with technology, belief systems and community ethics.

Donna Haraway proposes a kind of critical subjectivity in the form of Situated Knowledges.

“We seek not the knowledges ruled by phallogocentrism (nostalgia for the presence of the one true world) and disembodied vision. We seek those ruled by partial sight and limited voice – not partiality for its own sake but, rather, for the sake of the connections and the unexpected openings situated knowledges make possible. Situated knowledges are about communities, not isolated individuals.” [8] (Haraway 1996)

Furtherfield had run [HTTP], London’s first public gallery for networked media art, since 2004 from an industrial warehouse in Haringey. In 2012 the gallery moved to a public location at the McKenzie Pavilion in the heart of Finsbury Park, North London.

However, we are not just a gallery; we are a network connecting beyond a central hub.

“It is our contention that by engaging with these kinds of projects, the artists, viewers and participants involved become less efficient users and consumers of given informational and material domains as they turn their efforts to new playful forms of exchange. These projects make real decentralised, growth-resistant infrastructures in which alternative worlds start to be articulated and produced as participants share and exchange new knowledge and subjective experiences provoked by the work.” [9] (Garrett & Catlow, 2013)

The park setting informs our approach to curating exhibitions in a place with a strong local identity, a public green space set aside from the urban environment for leisure and enjoyment by a highly multicultural population.

We are simultaneously connected to a network of international critical artists, technologists, thinkers and activists through our online platforms, communities, and wider networked art culture. We get all kinds of visitors from all backgrounds, including those who do not normally visit art spaces. We are not interested in pushing the mythology of high art above other equally significant art practices. Being accessible has nothing to do with dumbing down. It concerns making an effort to examine deeper connections between people and the social themes affecting theirs and our lives. We don’t avoid big issues and controversies and constantly engage in a parallel dialogue between these online communities and those meeting us in the park.

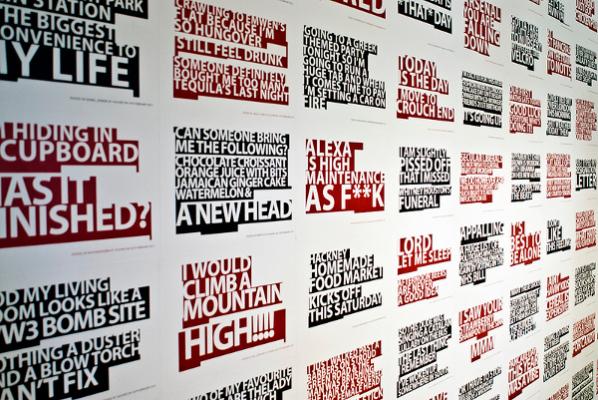

We feature works incorporating local people’s contributions, bringing them closer to the art and engagement of social dialogue. For instance, London Wall, N4 by Thomson and Craighead, reflected a collective stream of consciousness of people all around Finsbury Park, gathering their Tweets to print out and paste onto the gallery walls. By retweeting the images of the tweet posters, we gathered many of the original authors in the gallery to see their words physically located among others made in the vicinity.

Crow_Sourcing by Andy Deck invited people to tweet animal expressions from around the world – illuminating the link between the formation of human language and our relationships with other wild webs of animal life. Gallery visitors illustrated their animal idioms, drawing directly onto the gallery walls, inspired by the ducks, crows, squirrels and dogs that inhabit the park.

We feature works dealing with networked and pervasive technologies’ human and social effects. Web 2.0 Suicide Machine by moddr_ proposed an improvement to our ‘real’ lives by providing a one-click service to remove yourself, your data, and your profile information forever from Facebook, Twitter and MySpace, replacing your icon (again, forever) with a logo depicting a noose. They also reflect on new forms of exposure and vulnerabilities they give rise to, such as Kay’s Blog, by Liz Sterry, which replicated in physical space the unkempt bedroom of an 18-year-old Canadian girl based only on her blog posts, to eerie effect. The intention is to reach people in a way that has people question their relationship with those technologies. This does not mean promoting technology as a solution to art culture but exploiting it to connect with others and critique technologies simultaneously.

Below: Selection of images from original slide presentation – exhibitions & events.

On the 23rd of November, we opened our second space in the park, ‘The Furtherfield Commons’. It kicked off with The Dynamic Site: Finsbury Park Futures, an exhibition by students from the Writtle School of Design (WSD) featuring ideas and visions for future life in Finsbury Park, coinciding with the launch.

This new lab space for experimental arts, technology and community explores ways to establish commons in the 21st Century. It draws upon influences from the 1700s when everyday people in England, such as Gerrard Winstanley and collaborators, forged a movement known as the Diggers, the True Levellers, to reclaim and claim common land from the gentry for grassroots, peer community interests. Through various workshops, residencies, events & talks, we will explore what this might mean to people locally and in connection with our international networks. These include free software works, critical approaches to gardening, gaming and other hands-on practices where people can claim direct influence in their everyday environments in the physical world, to initiate new skills and social change on their terms. From what we have learned from our years working with digital networks, we intend to apply tactical skills and practices into everyday life.

Furtherfield is a network across different time zones, platforms & places – online & physical, existing as various decentralised entities. A culture where people interact: to create, discuss, critique, review, share information, collaborate, build new artworks & alternative environments (technological, ecological, social or both), examine & try out value systems. “A rhizome has no beginning or end; it is always in the middle, between things, interbeing, intermezzo.” (Brian Massumi 1987)

DADA, Situationism, punk, Occupy, hacktivism, networks, Peer 2 Peer Culture, feminism, D.I.Y, DIWO, Free Software Movement, independent music labels, independent thinkers, people we work with, artists, activism, grassroots culture, community…

This comprises technological and physical forms of hacking. It also includes aspects and actions of agency-generation, skill, craft, disruption, self-education, social change, activism, aesthetics, re-contextualizing, claiming or reclaiming territories, independence, emancipation, relearning, rediscovering, play, joy, being imaginative, criticalness, challenging borders, breaking into and opening up closed systems, changing a context or situation, highlighting an issue, finding ways around problems, changing defaults, and restructuring things – Claiming social contexts & artistic legacies with others!

This text is a re-edited slide presentation first shown at the ICA, London, UK, on 16th November 2013 (Duration 25 min). Intermediality: Exploring Relationships in Art. Speakers Katrina Sluis, Peter Ride, Sean Cubitt & Marc Garrett.

http://www.ica.org.uk/39077/Talks/Intermediality-Exploring-Relationships-in-Art.html

Transdisciplinary Community (TDC) Leicester UK 27th Nov 2013 (45 min). Institute of Creative Technologies. De Montfort University.

Two projects Gregory Sholette is currently involved in:

It’s the Political Economy, Stupid. Curated by Oliver Ressler & Gregory Sholette

http://gallery400.uic.edu/exhibitions/its-the-political-economy-stupid

Matt Greco & Greg Sholette | Saadiyat Island Workers Quarters Collectable, 2013

http://bit.ly/1eSI5kX

—————————————————–

All exhibitions, events & projects at Furtherfield – http://www.furtherfield.org/programmes/exhibitions

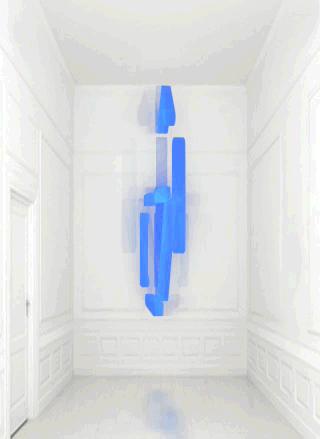

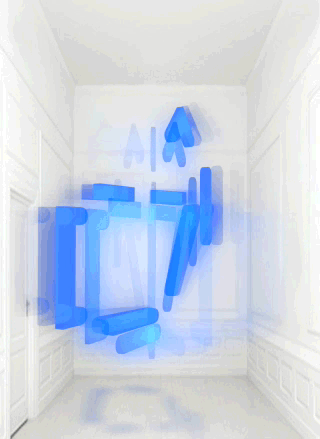

“a symbol of indeterminate meaning, floating/rotating into the empty white WAG room with no viewers” Bill Miller

Widget Art Gallery. July 17th – August 17th 2013.

Chiara Passa’s Widget Art Gallery (WAG) has been serving art online since 2009. Named for the ability to install the contents of its web pages as a Mac OS X “dashboard widget” or iOS icon, it presents virtual art objects against a standard backdrop or in a standard virtual environment that looks like a white-painted townhouse room repurposed as a small gallery space in an exclusive part of town.

The instructions for using the WAG are Apple hardware-centric, and as I don’t have an Apple device I had to cheat and view it on my GNU/Linux desktop. Digital art’s medium specificity consists in part of its reliance on the facilities of particular hardware and operating systems. This can be exclusive, not everyone owns Apple hardware, but it can also be realistic, Apple’s hardware currently defines computing in the popular imagination.

The image of the gallery in the widget, like the image of a leather desk organizer or a wire mesh microphone in an mobile app, or the very idea of “the desktop” in a desktop GUI, it is a skeuomorph. It is a non-functioning symbolic form that cues the viewer in to the affordances that the experience of the software offers. Like the white cube of a real art gallery, it frames the experience of looking at the artwork and emphasises its seriousness, value, and singularity.

From July to August 2013 the work inhabiting this virtual space is Bill Miller’s “A Symbol“. The titular icon is a composition of soft light blue graphic elements that look like ASCII art that are not aligned to a teletype grid. Or like a misaligned LED matrix. It evokes the art of early military computer games, or the more complex emoticons, or maybe a lamp or a teapot. It rotates, blurs, flickers and stops, glitching and returning.

Widget Art Gallery installations are presented as animated GIFs, but they are different from the usual hilarious recuperations of Compuserve’s low-bandwidth image format in their lack of all-overness and of mass media appropriation. Animated GIFs are often glitched, but with “A Symbol” it is the object depicted in the animated image that is glitching, not the image itself.

The rotating symbol used to be a staple of broadcast television identities. The flickering or glitching symbol signifies signal hacking, technical difficulties, or coming into or out of being by teleportation or rezzing. Popular culture reactions to technology emphasize its flaws and failures to make its smooth surfaces tractable to the imagination. But this symbol remains opaque and self-assured, always returning to its original state.

The symbol’s reflection on the floor pushes it into and anchors it in the imaginary space of the gallery. Like drop shadows in graphic design or the handling of shadows and highlights in paintings it is a visual spatial strategy to make its subject seem more real and in the same space as the viewer. The rhythm and pauses in its rotation, especially the pauses, make it seem intentional and sculptural, they give it a solidity in time as well as space.

The accessibility and framing of the Widget Art Gallery mean that “A Symbol” can travel with and be accessed by its audience over time in a variety of settings, making it even more a reflection of their lives. “A Symbol” is retro digital but with a contemporary electroluminescent aesthetic glow like a Tron Legacy costume or an Android startup screen, militaristic but emotive, hard-edged but glitching, opaque yet evocative. It is a sign of the times.

Anonymous, untitled, dimensions variable is the title of a show by 0100101110101101.ORG (Eva and Franco Mattes) at Carroll/Fletcher gallery in London from 13th April to 18th May 2012. Or at least it was. The title changes each day based on submissions to a blog (http://exhibitiontitlechange.tumblr.com/). The new titles have been printed out and displayed on the wall to the left as you walk in to the gallery.

You don’t expect this kind of playful intersection of the virtual and the real in a gallery off of Oxford Street, across from Soho, opposite other new galleries. Carroll/Fletcher’s glass-fronted welcomingly brutalist interior says “serious contemporary art space”. Inhabiting such a space presents a challenge to net and digital art that must be met with careful presentation and considered curation.

Through the glass front of the gallery, and as you enter, you see a sculpture or assemblage of a (stuffed) cat trapped in a birdcage by a (stuffed) canary (Catt, 2010). The cat has suffered Epic Fail as the Internet would say, and did in the meme image that the sculpture is based on. It’s a comic and unnerving object even without the extra layers of reference provided by the original meme and the knowledge that it was originally presented as a fake Maurizo Cattelan sculpture. It is art with its roots in the net that can stand on its own without that context. Its companion piece, Rot, 2011, is a fake Dieter Roth sculpture consisting of detritus in a glass jar on a plinth against the far wall. 0100101110101101.ORG briefly inserted it into the Wikipedia page on Roth, and the fact that its materials were all ordered via the Internet drives home just how commonplace this has become.

Both are given the room they need to work as objects in a gallery. Neither originates in itself as net art, more in 0100101110101101.ORG’s history of tricksterism and transgression. These are concerns that are easily linked to net culture, possibly too easily on the part of the reviewer, but it is telling that they are the works that the show opens with. They physically establish the playful appropriation and hyperreality that is the basis of much of 0100101110101101.ORG’s work.

Pride of place in the first room of the gallery goes to the projection The Others, 2011, 10,000 digital photographs (supposedly) copied without authorization from the folders of computers used by people on a peer-to-peer filesharing network that 0100101110101101.ORG used to distribute their own work. These are private images, projected at an angle and slightly across the corner. Configure your peer-to-peer filesharing client wrongly and it shares all the files in the folder you share. Including the images of you naked, drunk, lonely, partying, or whatever else you wouldn’t post anywhere a future employer might find them.

In the next, smaller, room is Colorless, odorless and tasteless, 2011. It is an old-fashioned car racing video arcade game retro-fitted with a petrol engine that starts up when you insert a coin and revs as you press the pedal to accelerate the virtual car on the screen, filling the (sealed…) room with carbon monoxide. Combining the virtual made physical of Catt and the moral impact of The Others, it is the most immediately dangerous artwork I’ve ever had to review.

Moving into the larger room at the back of the ground floor of the gallery, the video No Fun, 2010, is the most shocking piece in the show. Franco Mattes pretending to hang hineself on the random Internet webcam video chat switchboard Chatroulette is one thing, but the reactions of other Chatroulette users as they connect and see him apparently hanging there is quite another. Some laugh, some jeer, only one I watched displayed any lasting concern. This is the moral and aesthetic flipside of The Others.

Reenactments, 2007, is my aesthetic and technical favourite piece in the show. Videos of canonical performance art pieces being re-enacted by Eva and Franco’s Second Life avatars are displayed on CRT monitors arranged at floor level surrounded by the cables and adapters used to play back the video from SD cards. It’s much easier for an avatar to remain still as a “Singing Sculpture” than it is for a human being, making it even stranger, and Marina Abramovic’s “Imponderabilia” works much better with impossibly buff avatars than with mere naked human models stood in a doorway. It exquisitely foregrounds the social mediation of Second Life and its players self-presentation. A large cartoon wolf squeezes through between the naked avatars, their polygons intersecting. A vampire attempts to fly over them but hits the bounds of the architecture. The crowd in the background chat and bide their time. The virtual intensifies the real, out-doing and critiquing its appropriated source material.

Stolen Pieces, (1995, made public 2010) claims to move beyond fakery and unauthorized copying to physical appropriation. Stolen physical fragments of canonical postmodern artworks (Duchamp, Warhol, Koons, Rauschenberg) are displayed like forensic evidence, protected in small plexiglass containers, accompanied by large photographs of them and by documentary evidence of their theft. There’s no statute of limitation on theft in the UK, and damaging artworks shouldn’t be applauded. But it’s a daring performance and a concrete critique of the fetishism that lies at the heart of the art market and the institutions that help drive its value.

Following the brutalist concrete staircase to the basement reveals My Generation, 2010, a smashed but still working early-2000s PC lying on the floor. On its monitor, that appears to have fallen on its side, show video clips of computer game players giving in to and venting their frustration at the games they play. This isn’t the kind of image of yourself you want as your lasting monument on the Internet. Gathered together, like the images in The Others and the videos in No Fun, they again form a summation of an aspect of society and our visual environment that could not be achieved with such immediacy by other means. And the clear space and architectural solidity of the gallery again help to put a different emphasis on the material than if it was encountered on the web.

The wall-filling video projection of Freedom, 2011, records Eva’s attempts to plead with the players of networked First Person Shooter computer games not to kill her character. Touch-typing might have helped, but even when Eva manages to type long enough to explain that she’s an artist, or to ask people not to shoot, the social and game logic of the virtual world mean that her character is executed again and again, the screen shifting to third person as her avatar moves out of her control in death. Like No Fun, there is a core of callousness to these Internet interactions, and like My Generation they are unexpectedly preserved and presented for contemplation.

The final piece in the show is the documentary Let them believe, 2010, a video record of 0100101110101101.ORG’s Tarkovsky-haunted journey into Chernobyl’s “Exclusion Zone” in order to recover part of a fairground ride to turn into Plan C, 2010. Bringing part of the ride to life in a place where people can enjoy it is an effective and resonant symbolic resolution of the kind that art more than any other mode of human endeavor can provide.

0100101110101101.ORG’s work presented physically has more than enough presence to fill the gallery and benefits from the space and the considered curation afforded it here. Some of the work is more physical than virtual and vice versa, sometimes the ethics of the work place 0100101110101101.ORG as the villain sometimes as the victim, and sometimes the work is performance whereas other times it is assemblage. I mention this to point out both the strong themes to the work and how individual the effect of each piece is.

Net art in the gallery might seem a category error, like museum postal art. Or it might seem a commodity, like auctions of land art documentation. But net art is transitioning from being the contact language of artworld emigrants learning the net’s protocols to the contact language of net emigrants learning artworld protocols. 0100101110101101.ORG have made art of these encounters from the start, and have always been as at home in the gallery as on the net.

The text of this review is licenced under the Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0 Licence.

In February 2012 Furtherfield is opening a public gallery at McKenzie Pavilion in Finsbury Park, providing space for exhibitions, activities and events for art, technology and social change. Before we officially open we would like to invite local community groups and organisations to join us in a friendly networking event which we hope will be the first of many, leading to fruitful partnerships and collaborations.

Inviting Local community groups!

During the event, you will…

– Meet up, be seen, show what you do

– Get to know other organisations and discuss ways we can collaborate

– Inform Furtherfield as to what can happen in the space

We are living through times of great change and uncertainty. Over the next 18 months, Furtherfield hopes to provide a space for imaginative exchange between artists – international and local, of all ages and backgrounds – on epic and everyday themes. Our success depends on the quality of our conversations. We hope that this event will be the first of many that will lead to fruitful partnerships and collaborations. We are inviting local organisations and groups involved in the arts, education, community engagement and support, and all of those working in and running activities in the park.

A full list of confirmed guests will be made available at the event. Please tell us about people or organisations who are important to our area and or who might want to come along and get involved.

Refreshments will be provided.

Please RSVP to Alessandra Scapin, Furtherfield Programme Manager and Coordinator, on ale[at]furtherfield.org to confirm your attendance as the pavilion has limited capacity or on 020 8802 2827 (please leave a message – we are not always in the office)

For more information about getting to the gallery http://www.furtherfield.org/gallery/visit