The 22nd conference of the Disruption Network Lab, “HATE NEWS vs. FREE SPEECH”, explored polarization and pluralism in Georgian media, opening on 12 December 2020 in partnership with the Regional Democratic Hub – Caucasus.

Introduced by Tatiana Bazzichelli and Lieke Ploeger, the Programme and Community Director of the Disruption Network Lab, the two-day-event brought together journalists, activists and experts from based in Georgia and Germany to look into the manifestations as well as the consequences of information manipulation and deliberate hate speech within the Georgian media landscape.

The conference, held at Kunstquartier Bethanien in Berlin as a combination of online and on-site formats, investigated a hyper-polarised system, in which exploitative manipulation of facts and orchestrated attempts to mislead people through delivering false information are dangerously eroding media independence, pluralism and freedom of speech. In the context of deliberate technology-fuelled disinformation, spread by news outlets of religious and political influence, hostile countries and other malign sources, the work of independent Georgian journalists is often delegitimised by public authorities and denigrated in a wave of generalisations against media objectivity, to undermine independent information and stifle criticism.

As Bazzichelli stressed in her introductory statement, independent journalists reporting on information that is in the public interest are targeted because of the role they play in ensuring an informed society. At the same time, a global process of mystification is progressively blurring the boundary between what is false and what is real, growing to such a level that traditional media seems incapable of protecting society from a tide of disinformation, and becomes part of the problem.

Opening the first panel, “Polarization and Media Ethics in Georgia”, the moderator Maya Talakhadze, Co-Founder of the Regional Democratic Hub – Caucasus explained that, similar to other former Soviet Union countries, the political environment in Georgia has been polarized since the independence of the country. This has led to highly partisan media and to a marked divergence of political attitudes to ideological extremes within the around 3.7 million Georgians. Although the widespread of the internet guaranteed access to new media outlets and social media opened the way to a more pluralistic media environment, Georgian society soon faced the new challenges of widespread online disinformation, ethics violations and hate speech.

Professor Tamar Kintsurashvili, Executive Director of the Media Development Foundation and Associate Professor at Ilia State University, referred to Georgia as the country with the most pluralistic and free media environment in South Caucasus region. Nevertheless, according to Freedom House and Reporters Without Borders, its information system appears weaker and weaker, public broadcasters have been accused of favouring the government and lawmakers have repeatedly attempted to restrict freedom of expression.

Professor Kintsurashvili stressed how such an environment cannot be considered independent and negatively contributes to the polarization of the country. In her critical analysis, Georgian media pluralism could be described as the product of competing political interests, rather than a sign of strong freedom of expression and an independent press in the country. Despite this, Georgian civil society is widely praised for its diversity and strength.

In Georgia, most media have a political affiliation and align themselves with the agenda of a candidate or a party. This results in the actual instrumentalization of mainstream media and the concentration of ownership of TV stations, online media outlets and newspapers in the hands of the dominant political parties, which are shaping the overall media environment.

Professor Kintsurashvili recalled that in 2017 the ownership of pro-opposition Georgian TV channel Rustavi 2 was transferred to the businessman Kibar Khalvashi, its previous owner, after a ruling by the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR). The case is instructive of the complexity of the Georgian media landscape. Khalvashi’s opponents accused him of having close ties to the government and warned that the new ownership could not guarantee freedom of expression and independence for journalists and broadcasts. Following the ECHR ruling, two new opposition broadcasters emerged.

Professor Kintsurashvili highlighted that, to come to a full understanding of the country, one must consider the possible sympathies of the Georgian politicians toward the Russian Federation, despite the 2008 war and its continuous interferences in domestic affairs.

Many critical voices and independent investigations observe that Russia is supporting a galaxy of media outlets active all over the Caucasus, characterised by a lack of transparency and accountability. These actors promote anti-Western propaganda and are partially responsible for the radicalisation and antagonization of the Georgian society, leveraged to disrupt social cohesion and push the country away from the EU’s Eastern Partnership with the six countries of its Eastern neighbourhood –Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine.

Professor Kintsurashvili points out that while outlets such as Sputnik or Russia Today are openly funded by the Russian government or by Russian oligarchs, the ownership structures of dozens of online platforms remain unclear, and many vanish after a few weeks of activity.

In addition to this, the panellist considered that economic resources for independent media are limited and a lack of transparency of financing – especially in online media – which poses a serious problem for the independence and impartiality of many media outlets, as they are not accountable to the Georgian public but to their owners. Neutral newsrooms with no political affiliation are not self-sufficient and manage to have a small impact on the overall environment; nothing compared to big TV channels, which remain the major source of information in the country.

Taking a step from such a polarized environment shaped by domestic and foreign actors with a political agenda, the second panellist Nata Dzvelishvili, Executive Director at Indigo Publishing, focused on the current state of media ethics in Georgia and the lack of media literacy among Georgians. She considered that, in such a polluted disinformation ecosystem, the majority have almost no reliable instruments to orientate and discern good independent journalism, fake news and poor-quality reporting, which means also that the capability to identify verifiable information in the public interest, and information that does not meet precise ethical standards, is limited.

Dzvelishvili is the former Executive Director of the Georgian Charter of Journalistic Ethics, the self-regulatory body of media in Georgia. She pointed out that by decoding the authenticity of online news we can see how, alongside with the so-called fake news, there is also an alarming degree of laxity and journalistic errors arising from poor research and superficial verification. She listed a few frequent unethical behaviours and violations, from the lack of accuracy to unprofessional coverage of facts reported to arouse curiosity or broad interest through the inclusion of exaggerated or lurid details. In Georgia, this last aspect is mirrored in an unfair and hyper-partisan selection of facts, too.

The Georgian Charter of Journalistic Ethics – a body composed of 400 member journalists, which processes complaints and makes decisions on issues regarding ethical standards and principles – warned that Georgian media too often spread news based on unverified facts, or even simple errors, generating misinformation. Bad information undermines the credibility of media, and unprofessional journalism opens the way for widespread disinformation and misinformation.

Dzvelishvili explained that in Georgia the most critical topics subject to manipulation due to political interest are those related to religious sentiment, LGBTQI identities, migration and nationalism. In her intervention she presented examples of campaigns fuelling homophobia, racism and reopening historic traumas, fruitful ground for the growth of ultra-nationalistic, conservative, and pro-Russian narratives.

Many of the media outlets accused of spreading anti-Western and pro-Russian propaganda acted all over the Caucasus to disseminate disinformation about Georgia’s position on the Karabakh conflict, and thus foster hostility between ethnic Armenian, Azerbaijani and Georgian populations. Rumours and fully fabricated stories about Georgian Muslims ready to gain independence led to the concrete risk of a conflict between ethnic Georgians, the religious orthodox and Muslims, and represented a new pretext to call for Russian intervention to resolve the conflict. More recently, the COVID-19 pandemic was used to fuel anti-Western feelings, provoke mistrust in science, discredit Western democracies and divide the country.

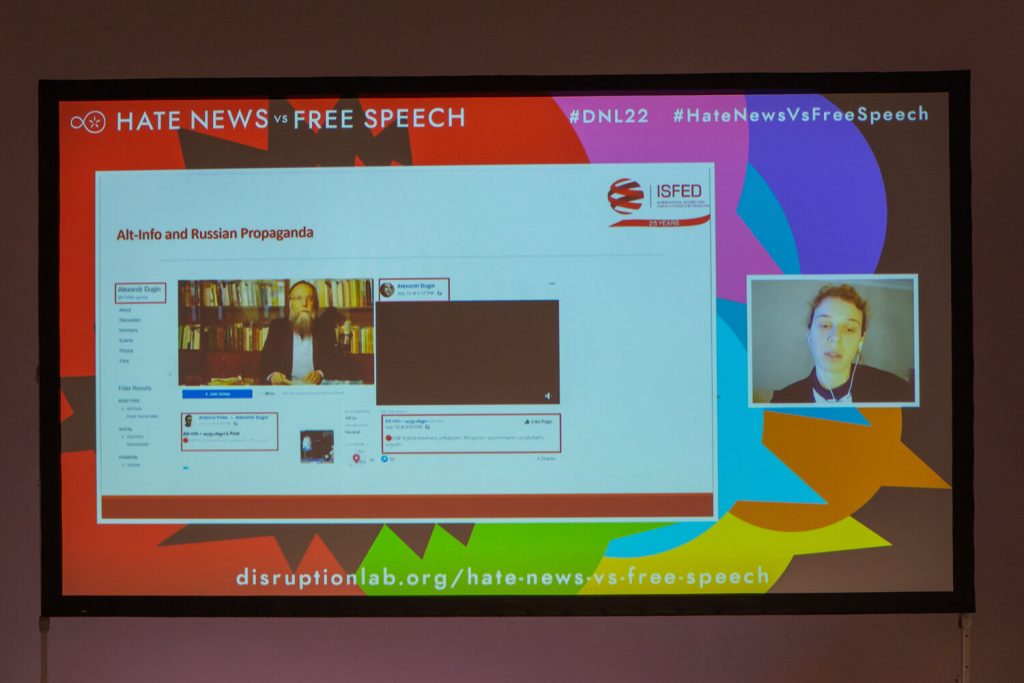

Nini Gvilia, Project Assistant for Social Media Monitoring at the International Society for Fair Elections and Democracy (ISFED), focused on social media in Georgia, which – she explained – 20 percent of the population use as their main source of information. Political activities have strongly shifted to Facebook and other social media, with the support of agencies such as The Marketing Heaven, which enables a more pluralised information environment but also sharpens the risk of misuse by malign actors.

News Front, a Georgian-language website, is one of these. Facts can be irrelevant against a torrent of abuse and hatred towards journalists and opponents, made possible by algorithms, fake accounts, coordinated bots and trolls, that generate viral postings on social media. News Front has also been active on Facebook since 2019. Analysing the interactions of its audience, it is observable that manipulation also arises by weaponizing memes to propel hate speech and denigration or creating false campaigns to distract public attention from actual news. Marginal voices and fake news can be disseminated by inflating the number of shares with automated or semi-automated accounts, which manipulate public opinion by boosting the popularity of online posts and amplifying rumours.

Many Georgians are still anchored to very traditionalist and conservative beliefs. Groups of right-wing extremists offer appealing online spaces filled with redundant rhetoric, gossip columns, sport blogs, and other apparently harmless content, which actually underpins anti-liberal, misogynistic, racist and homophobic views, pushing for a new authoritarian turnaround. Too often, mainstream TV channels and newspapers pick up staged news from such a disinformation ecosystem, enforcing a revisionist narrative built on manipulated facts and fake interactions, arrogance and violence.

Eka Rostomashvili, Advocacy and Campaigns Coordinator at Transparency International, moderated the panel “Misinformation on Social Media during Elections”. The opening contribution by Varoon Bashyakarla, Data Scientist at Tactical Tech’s Data & Politics Project, focused on how the ‘digital influence industry’operates. In addition, Bashyakarla dissected some of the dynamics that allow personal data to be weaponised for political purposes.

As he recalled, personal data of potential electors is being used constantly for political purposes – even without a precise agenda, just to spread disinformation. Hundreds of companies around the world profile people to influence and predict their political choices. Working with journalists, academics, and civil society organisations, Bashyakarla underlined how these tech firms exploit personal information as a political asset and source of political intelligence.

Many countries traditionally hold voter rolls containing basic information of their electors. Voters’ data is at the heart of modern campaigning and many of the companies working in consumers tech have opened new divisions dedicated to political technology – a term commonly used in the former Soviet states for a highly developed industry of political manipulation – to build statistical models that spy on voters to learn from their preferences and characteristics. Cambridge Analytica was just one of the many entities collecting and misusing intimate personal data to target and manipulate the electorate.

Last year, personally identifiable information of 4.9 million Georgians from 2011 appeared online. Many suspected that the leak was triggered to undermine voters’ faith in elections. However, a leak consisting of 200 million US-American voter files, with personal data including ethnicity and religion, had already demonstrated in 2017 – illustrating how risky election tech can be. The same happened in the Philippines, where the website of the government was subject to a cyber-attack and 340 gigabytes of the personal details of 55 million voters appeared online, and in Turkey, where in 2016 a leak of a 6.6 gigabyte file made available information of 50 million voters.

Bashyakarla discussed then how the extraction of value from political data works and explained the logic behind A/B testing, deployed to compare the performance of two competing advertisements. He warned that societies around the world are exposed to an unprecedented volume of testing. During the last US elections, for example, on the day of the third presidential debate a single online content could be shared in up to 175,000 different variations to test the reaction of the electorate.

Politicians test their postings, images, headlines and slogans to learn in which areas voters are more sympathetic to their messages; what causes in different regions of the country they care more about; and what topics are more likely to be appreciated by a specific audience. As Facebook suggests in one of its advertisements, these techniques allow you to “find the perfect match between your ad and your audience.”

In Georgia, the volume of unsolicited texting and even phone calls spreading political messages that electors receive before elections is overwhelming. Both pro-government political parties and opposition parties deploy similar tactics, which reach their peak point during elections. Coinciding with this very intense activity, the number of online pages spreading fake news triples, with hatred campaigns amplifying differences and fuelling polarization.

Mikheil Benidze, Chief of Party for the new Georgia Information Integrity Program at the Zinc Network, shared his observations on how social media platforms have been weaponized for electoral purposes and how Georgian civil society has risen to the challenge. In the next few years, the Georgia Information Integrity Program, run by the Zinc Network, is going to look into the activities of online users, to research why certain narratives are successful and what their actual impact is.

Benidze recalled that the web is full of traps, like fake news websites that look like the online version of mainstream newspapers, and TV channels, which deceive readers. These fake websites are used to co-ordinate campaigns and networks of political influence, propagate nationalistic, xenophobic, and homophobic content and to undermine the development of a multicultural liberal democracy. The panellist considered that algorithms amplify those messages even more, and praised Georgian civil society organisations for constantly debunking, exposing and analysing facts to protect a free, democratic and open debate. People get spontaneously together and mobilise to strengthen independent fact-checking initiatives and encourage the co-operation with social networks to monitor and delate online harmful content.

The panel was concluded by the contribution of Rafael Goldzweig, Research Coordinator at Democracy Reporting International, an independent non-profit organisation based in Berlin, which promotes political participation of citizens, accountability of state bodies and the development of democratic institutions worldwide. Goldzweig compared the trends observed in Georgia described throughout the first day of the conference with what happens in other countries. He offered an overview of regulatory approaches and initiatives – particularly those debated in the European Union – for making the online environment more resilient against disinformation, hate speech and other challenges.

The digital sphere and its interactions proved to be able to determine the course of elections and host activities, which can undermine the stability of a fragile institutional system. The researcher pointed out that, all over the world, social media has become subject to electoral observation, too, to monitor the rights of candidates and of the electorate.

Goldzweig is confident that more organisations and actors around the world can replicate the monitoring activities of Democracy Reporting International. He suggested that transparency and monitoring are fundamental to understand what happens online, and that we are facing a multi-stakeholder responsibility, since tech companies are asked to provide solutions and governments to maintain a central role. These actors must facilitate the monitoring by civil society and implement tech that enforces community standards able to guarantee individual and collective rights.

The first day’s guests presented a clearer image of the complex situation in the Georgian media landscape, in which disinformation and propaganda seek to animate people into becoming conduits of divisive messages and violence. All panellists expressed concern about the alarming levels of homophobia and xenophobia. Several contributions suggested that journalistic self-regulation and a respect for precise ethical principles appear to be the only way to guarantee strong and free information systems, keeping in mind that Georgian democratic institutions are still fragile and that lawmakers will try to implement new regulations as a leverage to limit freedom of expressions.

The conference’s closing panel, “Hate Speech & Human Rights”, was moderated by performer and journalist Azadê Peşmen. The talk opened with a focus on hate speech, violence and discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity in Georgia.

Giorgi Tabagari, Co-Founder and Director of Tbilisi Pride, gave the audience the chance to learn more about LGBTQI rights in the country. Georgian legislation directly prohibits discrimination against all LGBTQI people, nevertheless – as set out in the previous panels of the conference – there is a high level of hostility against queer people everywhere in Georgian society. Gay and transgender people, along with Jehovah Witnesses, Muslims and Armenians, are publicly presented as national enemies and homosexuality is considered an inexcusable moral corruption.

In Georgia the simple existence of LGBTQI people is a taboo. The mainstream media do not consider sexual and gender identity outside the binary representation of heterosexual men and women. Queer people appear to be the most despised group in the society, which is a fact taken for granted as a normal aspect by most Georgians. Tabagari recalled that an effective way to inflict a damaging insult and to ruin the reputation of a Georgian is to accuse that person of being homosexual: a moral corruption, worse than being a criminal.

The Georgian Orthodox Church has played a defining role in this. Not only does it condemn homosexuality as a sin, but it is also the front line of a violent mobilisation of individuals against queer people. For years, homophobic views have been encouraged by public officials and deployed to delegitimise and discredit political opponents. Investigations found that far-right and hate groups behind these actions were often linked to official parties sitting in the institutions.

By and large, Georgia is a conservative, homophobic country. Many participants of the conference could confirm that less hateful content has been hosted on traditional media in these last two years, whilst social media has been used to build a network of hateful content and online misinformation campaigns targeting LGBTQI activists. Hate and violence have been increasing for a long time, Tabagari warned. Due to more frightening levels of stigma and hatred, LGBTQI people and activists face constant and enormous challenges in Georgian society. Hate crimes and abuses revealed also to significantly increase the risk of poor mental health, from which many queer people suffer. As of today, no statistics about crimes conducted on sexual orientation or gender identity grounds in the country are available. However, it is obvious that the Georgian law prohibiting hate crimes, alone, is not sufficient.

The second panellist, Nino Danelia, Head of Journalism and Media Research at Ilia State University and Founder of the Coalition for Media Advocacy, discussed the implementation of existing national and international human rights standards to combat online hate speech in Georgia.

As described throughout the conference, the Georgian media landscape appears to be a competitive pluralistic system, but highly polarized. Danelia reported that television remains the main source of news and information for the majority of the country, whilst 25 percent of Georgians use internet – and particularly Facebook – to get informed.

On paper, Georgian laws meet international standards, as the country sanctions all forms of expression promoting or justifying racial hatred, xenophobia, and religious based intolerance, including aggressive nationalism and hostility against minorities and migrants.

Hate speech is not criminalised and it is regulated de facto by the Law on Broadcasting and by the Code of Conduct for Broadcasters. Danelia also warned that – in the fragile Caucasian democracy – a new regulation of hate speech could be a threat to media and editorial independence.

Danelia concluded her intervention by explaining that, in her opinion, the issue of polarised, controlled and impartial media can be tackled by strengthening existing self-regulatory mechanisms and funding professional training for journalists. According to the Georgian Charter of Journalistic Ethics, reporters must exert every effort to avoid hate speech that can cause fragmentation and radicalisation of the society.

Political leaders are asked to be careful and avoid violent and ambiguous expressions in their public speeches – not to facilitate, incite or justify hatred founded on intolerance and identity-based convincement. A delicate aspect is still represented by those political groups that propose to prohibit “offending the religious sensibilities or feelings”, which would constitute an area of legal uncertainty and arbitrariness, negatively affecting free speech.

Josephine Ballon, Legal Head at Hate Aid, gave an overview of the German legal perspective on hate speech, beginning from the fact that 78 percent of German internet users have already witnessed hate speech on the internet, whilst 17 percent have been a direct victim of these practices. Researchers calculate that, also in Germany, only 5 percent of users are responsible for almost 50 percent of hateful content.

Balloon recounted an example of neo-Nazis, united under the label “Reconquista Germanica”, and the Austrian Identitarian Movement, pointing out that an official 2019 investigation proved that 70 percent of the hate crimes and hate comments on the internet reported to the authorities were executed by far-right movements.

Such a violent spread of hate intimidates people. Not just those directly targeted, but the majority of internet users admit to being afraid of expressing their political opinions on the internet, fearing the campaigns targeting those who speak out. More precisely, Ballon reported that more than half of the people interviewed do not dare to express political opinions online, as they are afraid of the possible consequences.

The lawyer gives counselling to those who are affected by hatred and discrimination online and teaches them how to protect their data. Personality rights can be defended by directly suing the person responsible of the offence.

Georgian far-right and anti-liberal groups are strong enough to try to influence public opinion, backed by Russian propaganda, and this radicalisation seeks to fragment society even more. Both in Germany and in Georgia, journalistic standards are not applicable to social media and to user-generated content. In 2017, Germany introduced one of the most advanced laws regulating online hate speech at the time, the Network Enforcement Act (NetzDG), requiring internet companies to remove offensive content within 24 hours, or to face up to 50 million euros in fines. Other countries that tried to regulate the same subject ended up approving unconstitutional laws.

The importance of tolerance between diverse groups is stressed in the Georgian national Constitution, which guarantees and defends citizens’ fundamental rights and freedoms. Moreover, the law on broadcasting foresees a ‘National Communications Commission’ to regulate telecommunications and broadcast media. The Commission is supposed to be an independent regulatory body accountable to the legislative, but its practices are often criticised, and it is accused of being loyal to the executive branch.

In Georgia, 80 percent of the population who use the internet have a Facebook account. Zuckerberg’s company is the most popular social network in the country. During the last elections, the tech firm came under a lot of pressure from civil society asking to enforce effective measures to stop hate speech and fake news interfering with the democratic process. Twitter is less popular in Georgia, hosting more international users, who mostly write in English. Recently, social media platforms demonstrated themselves to be able to co-operate with local non-governmental organisations to monitor online content. These activities led to ban, and the shut-down of many pages. However, concerns have arisen considering that, between elections, as civil society lets its guard down, those same groups are free to proliferate and spread their content again.

Some keywords resonated throughout the conference, as a fil rouge connecting the speakers and debates held during the panels and commentaries by the public. Participants warned that the era of self-regulation of online social media platforms must come to end, as they have proved that their ruthless interest in clicks, interactions and profit comes before democracy and human rights. For almost a decade now, the spread of disinformation and misinformation through websites, social networks and social messaging has been begging the question of the extent of regulation and self-regulation of the companies providing these services.

On the other hand, the executive and legislative interference in the Georgian courts remains a substantial problem in the country, as does a lack of transparency and professionalism surrounding judicial proceedings. For these reasons, self-regulation remains the only plausible option for editors and journalists.

Media literacy and awareness-raising have been widely recognised as effective and reliable tools to oppose the spread of harmful content and, at the same time, tackle the system of disinformation and violence threatening Georgia. Education, together with strong independent journalists, who know and respect journalistic standards.

On the other hand, we see that economic uncertainties – fear, anger, and resentment – are leveraged to spread campaigns of hatred, attack opponents, discriminate minorities and activists. Conspiratorial, paranoid thinking and violent interactions act like a catalyst, provoking participation and fascinating individuals. Considering that it is all about the benefits of personalised advertising, and ultimately the need for clicks, many observers think that social media will never renounce to such a source of profit.

The collaborative project “HATE NEWS vs. FREE SPEECH: Polarization and Pluralism in Georgian Media” had its first phase between September and October 2020, with two trainings in Georgia on traditional and non-traditional journalism, organised by the Regional Democratic Hub – Caucasus. The announcement of the training triggered high interest, with 120 applications received for 30 places. The first training in Georgia was held in the Kakheti Region involving journalists, (social) media representatives and bloggers from the eastern regions of Georgia. The second training, which took place in October in the Samtskhe Javakheti Region, was held for the students of journalistic faculties with special focus on the regional universities. The training sessions addressed several key areas, among them digital and media literacy, media ethics, hate news and hate speech.

The project ended with this conference and a workshop in Berlin titled “Anatomy of a Conspiracy Theory”, run on December 13 by researcher, trainer and consultant Alistair Alexander, with participants from both Tbilisi and Berlin. The workshop discussed several conspiracy fantasies from around the world, to understand what makes them work and how to challenge their circulation.

HATE NEWS vs. FREE SPEECH provided a forum for discussion and on complex issues, with particular attention for different perspectives of the international guests – especially women – who animated the debate.

For further details of our speakers and topics, please visit the event page: https://www.disruptionlab.org/hate-news-vs-free-speech

The 23rd conference of the Disruption Network Lab, curated by Tatiana Bazzichelli, was titled “Behind the Mask: Whistleblowing During the Pandemic.“ It took place on 18-20 March, 2021.

You can re-watch the panels here: https://www.disruptionlab.org/behind-the-mask

To follow the Disruption Network Lab sign up for the newsletter and get informed about its conferences, meetups, ongoing researches and projects.

The Disruption Network Lab is also on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram.