The first interview with Jake Harries, took place on one of Furtherfield’s Radio broadcasts on Resonance FM, earlier this March 2011. Fascinated by the historical context that came out of the radio discussion, we asked Jake for a second interview, this time it took place via email.

Jake Harries has been making music in Sheffield since the 1980s and is a sound artist, musician/producer, composer and field recordist with a strong interest in media art and the practical use of Open Source audio-visual software. He was a member of electronic funk band Chakk which is best known for building Sheffield’s first large recording studio, FON Studios, in the mid 1980s. He is currently one of “freestyle techno” trio Heights of Abraham and The Apt Gets, a band which uses guitars and only Open Source software on recycled computers to create songs from spam emails. He is Digital Arts Programme Manager at open access media lab, Access Space, and the current curator of the LOSS Linux Open Source Sound a website dedicated to music made with FLOSS.

Marc Garrett: Lets talk a bit about your own history first. You were in a band in the 80s called Chakk, could you tell us a bit about that?

Jake Harries: Chakk was based in Sheffield during the mid 80s and we are best known for building a heavily used facility, FON Studio, Sheffield’s first large commercial recording studio. Chakk made “industrial funk” music, a mix of funk base lines and drums with influences ranging from punk to soul to free jazz and electronica. Our music was aimed squarely at the dance floor. We believed that technology, in this case the recording studio, was the most important instrument a band could have both creatively and financially.

MG: So, you are part of the electro music history of Sheffield with bands like Cabaret Voltaire & The Human League in the late 70s – 80s?

JH: Yes, but the band itself didn’t have too much commercial success, a couple of indie chart top 10s and a couple of low 50s in the main UK chart, so few people remember us now. People are more likely to remember FON Studio.

Recently a documentary has been made, called The Beat Is Law, about Sheffield music at that time, so perhaps there will be a bit more interest in the band.

MG: Open Source software is freely downloadable from the Internet for free and Linux is the most widely used Open Source operating system. How long have you been using Linux operating systems and Open Source?

JH: I had heard of Linux before, of course, but I came across music applications which were developed only for Linux in 2002-3 while searching for new software tools. These intrigued me sufficiently to install the operating system on a pc which I had fixed where I was working at the time.

MG: Do you feel that artists, techies and others are choosing Free and Open Source resources for reasons which connect with ethical and environmental issues and concerns?

JH: Well, I’d like to integrate into this answer the general themes of openness and transparency. FLOSS is akin to an encyclopedia of how to make things in the software realm because all the code is available for anyone to download and develop; closed, proprietary software is like a “sealed box” which it is illegal to prise open.

But it goes a bit deeper than that: in the world we are living in now the “sealed box” is increasingly becoming the mode of choice for all kinds of products, most of which, because they are designed to be superseded, have built in obsolescence. When something goes wrong with a product, you are unable to fix it yourself because you can’t get inside it, and even if you could you can’t find out how to fix it. If it is out of warranty, either you pay a lot of money to get it fixed or you throw it away; then you buy a new one! (Which is what the market wants you to do…)

So, it feels very much as if we are surrounded by technology we are not encouraged to understand and products with a limited life span: the obvious environmental concern is, “what happens to my ‘sealed box’ when I throw it away?”

Using a Linux operating system can increase the useful life of a computer by several years, and perhaps, if you can hack into them, other products too. So it is great if both hardware and software are open.

We also know that sharing knowledge is generally considered to be a good thing as it allows people to build on what has already been discovered. Being able to give the people in workshops the software they have been learning to use because it is FLOSS, rather than them having to pay several hundred pounds because it is only available on a commercial license, is great and often the idea of this kind of freedom takes a while for people to get used to if they’ve not come across it before.

MG: Why is it important as a creative practitioner to be using Open Source?

JH: Well, personally, I have realised that what I’m interested in is freedom, not just as a hypothetical, but the practical reality, finding out how to achieve some of it and if it is possible to sustain it. Free & Open Source operating systems and software are one way of stepping out side of the constant pressures of the commercial market places which dominate our culture.

We tried this in Chakk in the 80s with FON Studio, attempting not only to personally own the means of producing our music, the studio (allowing us to be outside the corporate system of production), but also to be able to explore our creativity in the way we wanted to. In the case of Chakk it didn’t work out. We had, rather cheekily, persuaded a giant corporate (MCA Records, owned by Universal) to bank roll it all and they found ways of scuppering our plan by making our product conform to their idea of the market place: transforming it into something “radio friendly” and bland, taking the energy and urgency out of the music. We were quite a politicised band and that energy was essential to our musical integrity.

However, when MCA dropped us we had a recording studio which could help nurture new music without too much external pressure, and this led to records produced there by local acts fulfilling their potential and going into the charts.

I think it is important for artists to have certain freedoms, to have ownership over the means with which they create their work. The fact that FLOSS allows you the user the potential of customising the tools you use and to distribute them freely via the web or other means is quite profound. And one of the real benefits of using FLOSS as a creative practitioner are the use of open standards and formats.

MG: OK, let’s move onto your own band: The Apt Gets. Now, since The Human League & Cabaret Voltaire, a whole generation has experienced the arrival of the Internet. Your group seems to reflect this aspect of contemporary, networked culture – a kind of Open Source rock band. Could you tell us about this band The Apt Gets, how you all got started and why?

JH: It began with workshops I was leading for musicians on FLOSS audio tools in 2007. The idea of an “open source rock band” came up – at the time we didn’t think there was one so a couple of the workshoppers and myself formed one. The Internet was the main source of inspiration really: we used recycled computers with Linux we’d downloaded, as well as guitars and vocals. I’m interested in re-purposing junk as raw material for creative processes and decided to re-use some of my spam emails as lyrics. We all hate spam, but re-contextualising it like this is fun, as is introducing a song by saying, “Here’s a classic Nigerian email asking for your bank details”. The themes of spam emails are generally things like greed & money, status & sex appeal as well as “meds”, so there’s more to them than you might think.

MG: Now, I personally know why, but others who are not as familiar with Linux and Open Source Operating systems, will not immediately know this. The naming of your band’s name – it’s specific to installing software. Could you tell us more about that?

JH: On a Debian Linux based operating system one can install software from the internet using an application called apt. One could type apt-get install the-name-of-the-software into the command line and apt will get the software from what is called a repository on the Internet, where the software is stored for download. We thought that if you called someone an Apt Get it could be interpreted as an insult meaning something like, clever bastard. So, that’s why we named the band The Apt Gets.

MG: How long has your research project with FLOSS been going?

JH: The research project started in 2007. Ever since I began to use FLOSS I’ve been interested in the practical realities of using it, particularly as an every day set of tools, as an ordinary computer user would use it: for instance, when I do work on the arts programme at Access Space I don’t use anything else. So, it made sense to discover how a number of non-Linux using musicians would find using FLOSS audio tools – if I was being an advocate for FLOSS I ought to look at it from the new user’s angle and discover how far they could go and what kind of time scale they need.

MG: And the web site address is?

JH: http://audiotools.lowtech.org

MG: How easy is it for someone with little or no experience of Open Source software and Linux based operating systems to install it?

JH: It is quite easy nowadays. A Linux distribution like Ubuntu has an easy to follow installer which allows you to create a dual boot if you want it, that is, keeping your Windows system as well so you have the choice of both.

MG: At Access Space in Sheffield, you are curator and researcher of LOSS (Linux Open Source Sound) a website dedicated to music made with FLOSS – which is basically LOSS with the letter ‘F’ added, meaning ‘Free Linux Open Source Sound’ – FLOSS!

JH: Yeah! Free is the word! It is a repository for music made with FLOSS tools and released under a Creative Commons license. You can freely download and upload tracks. Initially it was based around two projects, a physical CD issued in 2006 curated by Ed Carter, and LOSS Livecode, a mini conference and gig curated by Alex McLean and Jim Prevett based around the international livecoding community. The website is at http://loss.access-space.org.

MG: What is Access Space and what is different about them as a group?

JH: Access Space is an open access media lab, based in central Sheffield. It uses reused and donated computer technology to provide Internet access and Open Source creative tools, free of charge, five days a week. It started in 2000 and has become the longest running free Internet project in the UK.

We recycle computers, put on art exhibitions, creative workshops and sonic art events. We’re currently developing a DIY Lab, modelled on MIT’s FabLab or fabrication laboratory. This will be an interface between the physical and digital domains where new kinds of creative activity can be developed.

MG: What operating systems would you suggest to newbies coming to Linux for the first time?

JH: Ubuntu or its derivative, Linux Mint, are both very user friendly for everyday use. For audio try Ubuntu Studio, 64 Studio or Pure:dyne.

MG: And regarding yourself, what are you using?

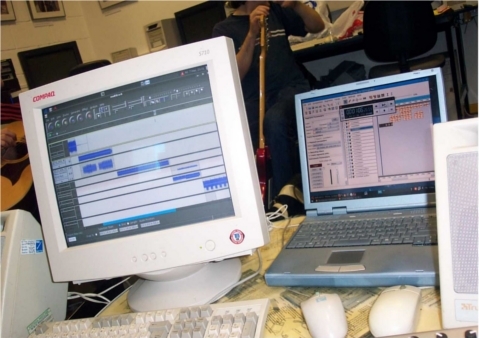

JH: I have set up eight Ubuntu Studio pcs for use in audio and video workshops at Access Space; and I use Pure:dyne live DVDs if I’m out and demonstrating on other people’s pcs. For everyday use, again Ubuntu Studio with a few additional applications like OpenOffice.

MG: Thank you for a fascinating conversation.

JH: It was a pleasure…

Open Access All Areas: an Interview with James Wallbank about Access Space by Charlotte Frost

http://www.metamute.org/en/Open-Access-All-Areas

Ubuntu Studio 11.04 release.

http://ubuntustudio.org/

64 Studio Ltd. produces bespoke GNU/Linux distributions which are compatible with official Debian and Ubuntu releases. http://www.64studio.com/

Puredyne is the USB-bootable GNU/Linux operating system for creative multimedia.

http://puredyne.org/

Pure:dyne Discussion, interview by Marc Garrett & Netbehaviour list Community 2008.

http://www.furtherfield.org/interviews/puredyne-discussion-netbehaviour

Helen Varley Jamieson’s account of working collaboratively in Madrid at the Eclectic Tech Carnival. On a ‘sprint’, with five women coming together for a week to rebuild the group’s website, physically & remotely.

In the last week of June I went to Madrid for the Eclectic Tech Carnival (/ETC) website workweek – the collective effort of five women coming together for a week to rebuild the group’s website. This is sprint methodology, a concept that I first met in Agile software development, but one that is being increasingly applied as a successful creative collaboration methodology. During the workweek I blogged about the process and this article is an assemblage of the blog posts.

Thinking about the concept of the sprint, I realised that over the years, I’ve participated in a number of theatrical “sprints” although we didn’t call them that. In fact it could be argued that the normal development process for theatre productions in New Zealand is the sprint – a three or four week turnaround of devising/rehearsing/presenting. Except that it doesn’t usually continue the Agile process after the first sprint – evaluation, refinement then the next sprint and iteration – and as a result, the work is often undercooked. But theatre projects that better fit the sprint analogy are some of the workshop-performance processes that I’ve participated in at theatre festivals, where a small group comes together for a few days to create a performance, then some time later meets again in another situation, perhaps a slightly different configuration of people, for another sprint. Each sprint generates a stand-alone performance or work-in-process showing, as well as contributes to a larger evolving body of work that forms the whole collaborative project. Two such projects that I’ve been part of are Water[war]s and Women With Big Eyes (with the Magdalena Project).

Recently I participated remotely in a Floss Manuals sprint, developing a manual for CiviCRM (which is something that I use with the Magdalena Aoteroa site). In this sprint, a group of about 15 people met somewhere in the USA to create a manual for CiviCRM. A few more of us were online, doing things like copy-editing the content. Most of the time there were people active in the IRC channel, chatting about the project and other things going on around them, so I got a sense of their environment, time zone and the camaraderie generated by the intense process.

Sprinting seems like a very logical and effective way to work in many situations: in software development, where each sprint focuses on specific feature development, and allows for a lot of flexibility and adaptation as the project progresses; in theatre, where limited resources make it a practical way to work, and the time pressure forces us to be resourceful and imaginative and also with networks, such as the Eclectic Tech Carnival, whose organisers don’t get to meet physically very often. It also makes sense in the context of our hectic lives, to block out a week or a few days when we agree to put everything else on hold and commit to intense, focused work instead of trying to juggle and multitask, with deadlines pushing out and out.

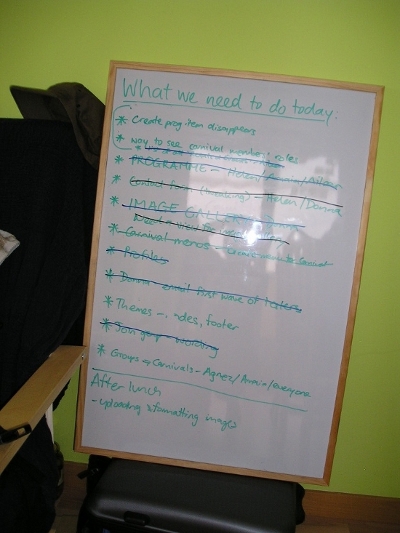

By halfway through the second day of the workweek, the wiki we used to plan and manage the project was filling up with tech specs, user requirements, design ideas, etc. We were getting encouraging emails from others in the network, and chatting to each other across the table and in the IRC. After lunch we did the new Drupal install and things seemed to be moving forward quickly in an organised and collaborative way.

Wednesday afternoon and the heat was oppressive; I put a little rack under my laptop because she was so hot, and my hands were too sweaty to use the trackpad. It wasn’t just Madrid’s weather that was making me sweat – we’d all been working hard on the new site since our late start in the morning (following on from a late night …). Agnes was busy developing the theme for the site, Aileen was working on profiles and user roles while Donna and Amaia were trying to configure mailing list integration and I was using the command line to drush download modules – much easier and quicker than the process of downloading, unpacking, ftp-ing and installing! And very exciting for me to use the command line, which I generally only get to do when hanging out with the /ETC crowd.

We were in that murky middle phase of the process: we’d done a lot of groundwork in terms of defining users, content types, general structure and the functionality required, but everything was still very bitsy and amorphous. But the installation of the test site had happened very easily yesterday, using drush, so that meant we now had something tangible to work with.

Working with Drupal can be pretty frustrating; it seems that every step of the way, another module is required to do what we want – then that module requires other modules, and then every little thing has to be finely configured to work just right with every other piece of the puzzle. From my previous experience with the Magdalena Aotearoa site, I knew we are doing a lot better this time in terms of defining what we need first, but some things we just can’t define until we know what’s possible, which we don’t really know for sure until we actually try it. We *think* we’re going to be able to do everything we want, but getting there isn’t simple. Also, the naming of different components and modules is sometimes ambiguous or confusing – the documentation ranges from really clear and detailed to non-existent. And some things just didn’t seem intuitive to me.

But, with five brains and our different complementary experiences and skills, I was still confident that we would have a new site by the end of Friday; maybe not a completely finished one, but a web site is never finished, is it?

On Friday morning the heat broke with a thunder storm and cooling welcome rain, but it didn’t last long. For some reason I woke up at 7.30am, ridiculously early as we hadn’t gone to bed until 2am. But I was wide awake so I enjoyed a couple of hours of quiet before everyone else awoke, drinking coffee and answering emails. The day before, Agnez and I had got up early to do yoga on the terrace, but the intense rain prevented that on Friday.

The test site was up and some of the others not present in Madrid were looking at it and trying things out. We’d solved a lot of problems but there were still a number of things not working. I had learned heaps about Drupal in the previous four days, particularly about organic groups, roles, permissions, and views. Altogether it is potentially incredibly flexible and powerful, however it takes time to work out how things need to be done and sometimes it is a confusing and circular process. Changing a setting in one place can stop something in a completely different place from working. However the combination of skills and experience between the five of us meant that usually one of us had at least an idea about how to do things and a couple of times we drew on external expertise via IRC or email.

On the last day, Agnez worked on finishing the theme while Aileen and I tried to work out why our groups are no longer displaying in the og_my view, and how to make the roles of group members visible. Donna had found that mailhandler and listhandler didn’t seem to be a practical way to integrate our mailman lists with Drupal after all – for the time being we’ll stick to the old system – and Amaia had been working on a way to create a programme for each event. The idea is that each /ETC event can be created as an organic group with the organisers having control over content and members within that group, but not being able to edit the rest of the site content. By Friday, we had this working pretty much how we wanted it.

We had planned a barbecue to celebrate the end of the workweek, but the rain prevented that. Instead, we ate inside then took turns to suffer humiliation and defeat with Wii Fitness (Amaia had clearly been practising!). In fact it wasn’t really the end of the sprint – rain again on Saturday morning meant that we decided to keep working longer and only went into the city in the afternoon, for a wander around and then the Gay Pride parade. On Sunday as we began to scatter back to our different parts of the globe, the site was still not live, as we were waiting for more feedback from testers and the finishing of the design themes. However, the site is essentially functional and should be live very soon.

The sprint process enabled us to achieve a considerable amount in a short space of time, sharing our knowledge and developing our skills. We also had great conversations over meals, explored Madrid and Colmenar Viejo, learned how to make Spanish tortilla, attempted a bit of Spanish, went swimming and did yoga. I even fitted in a performance on the first night, with Agnez, and dinner with friends another night. It’s amazing what you can do when you put the rest of your life on hold for a week; the only downside is the catching up afterwards.

Featured image: make art is an international festival focusing on Free/Libre/Open Source Software (FLOSS), and open content in digital arts

make art, one of the world’s most important free and libre art events, happens far away from the European metropolis, in the small town of Poitiers. However, it does not represent an integral piece of the ville‘s agenda to favour cultural tourism and development, as we might suppose thinking of some Brazilian film festivals and even of Bilbao’s Guggenheim. If something is to blame, it should be the grassroots effort of the native GOTO10 collective.

The name might sound familiar because not long ago they were doing a series of workshops in the UK to introduce FLOSS tools using their own pure:dyne operational system – a GNU/Linux distribution for multimedia creation. Having received some funding from the Arts Council, pure:dyne recently grew in efficiency and popularity.

Personally, the first time I heard about GOTO10 was in 2006, at that year’s Piksel festival. Some of the group’s members were there for audiovisual performances. Yes, they are artists as well – in fact, on the same days of make art, the group was taking part in the Craftivism exhibition, in Bristol. And between producing events, engineering software and, well, making art, they also found time to publish a book.

As diverse as these projects might be, they can all be inferred from the GOTO10’s creative practice, in respect of their real time interaction with people (in workshops) and machines (in live coding, etc). Given the way make art, pure:dyne and the group’s performances are interconnected, we could see them as one and the same activity, extending itself to various platforms.

I wouldn’t go as far as to say that, similarly, GOTO10 is a poitou group that has been expanded to other parts of the world. But, now that it has members from Greece, the Netherlands, Taiwan and the UK, the localization of make art seems even more meaningful to the collective’s identity, hinting on where and why it started.

According to Thomas Vriet, one original member who is still in town and mainly responsible for make art production. The group first got together in 2003 to promote digital art performances, workshops and exhibitions in Poitiers – sharing thoughts and ideas on things they were interested in, but could not find in the local art scene or École de Beaux-Arts.

So, in the same way pure:dyne was developed to cope up with GOTO10’s own needs for a live operational system capable of realtime audiovisual processing, make art is the ideal festival they’d wish to attend in town. Both projects find their reason in the group’s artistic demands, and grew simultaneously from it: the inaugural version of the distro was released in 2005, right on time to be used in a workshop in the first make art the following year.

Even though make art’s production is concentrated locally, the event is curated online, by the whole of GOTO10. The other member directly implied in this year’s planning, Marloes de Valk, arrived from Amsterdam just in the first day of the festival. make art is a group initiative that cannot be isolated from the larger open source community – a circuit that includes not only artists and programmers, but other venues as well. It is from this sizeable repository that the pieces that constitute the event’s programme come from. The aforementioned Piksel, for instance, has previously contributed to make art with a special selection of Norwegian works, creating an unexpected interchange between Bergen and Poitiers.

Together with the different Pixelache editions, these festivals form an international calendar of FLOSS art events, closely committed to developments in technology and aesthetics that, in many senses, are far more interesting that the new media proofs-of-concept proliferating elsewhere. But how does such package of extraordinary themes work in the traditional platform of the French countryside?

Altogether, make art seems to be the right size for Poitiers – not too small to feel incomplete, neither too big to feel overwhelming. The night programme may put you off if you are on a budget and decided to stay in the youth hostel (like me): there are no buses to that area after 8pm, forcing you to endure a half hour walk through cold streets. Apart from that, the city space is very well occupied by the festival, with the exhibition and debates in the central Maison de l’Architecture and a couple performances in other venues, emphasizing the curatorial logic. Posters are everywhere in town, competing for attention with those from the film festival.

However, the participation of the poitou community seems very restricted. So far, no local project has ever been sent in response to make art’s call. It might be that the theme is still alien to most people. Not surprisingly, the activity that attracted the majority of local public was the debate “Internet, Freedom and Creation” – which, beyond dealing with themes of more general concern (digital freedoms and copyright), was in French.

One of the efforts to increase this involvement was to open free places in the Fork a House! workshop to local students. Student volunteers could also be found mediating the exhibition and assisting production.

In that sense, the project that seemed to make the most of the festival’s situation was the frugal Breakfast Club. The first of these morning talks hosted by Nathalie Magnan was especially refreshing after the highly technical presentations the day before. Complex subjects were re-discussed over croissants, bringing the tone and rhythm of the event closer to the atmosphere of the #makeart IRC channel (which sometimes was livelier than the physical space).

The priority of Breakfast Club was not transparent accessibility but dialogue. Less of a tutorial and more like the public forum an open-source project cannot really do without. It made things more understandable to a laymen’s audience; it made the whole festival experience more coherent, pointing to directions in which it should grow within the city’s everyday life and structure – without having to be included in Poitiers’ tourism department masterplans.