Introduction

Marc Garrett, curator of the current incarnation of the Children of Prometheus exhibition at the NeMe gallery, interviews artist Joana Moll about the artwork, The Virtual Watchers, developed in collaboration with french anthropologist Cédric Parizot.

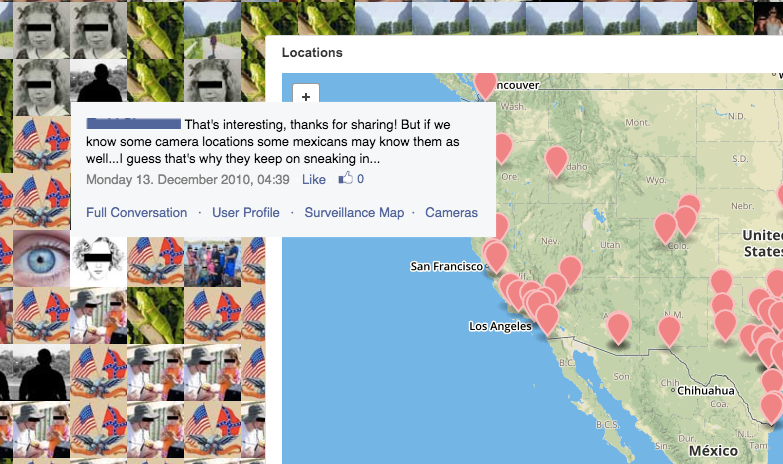

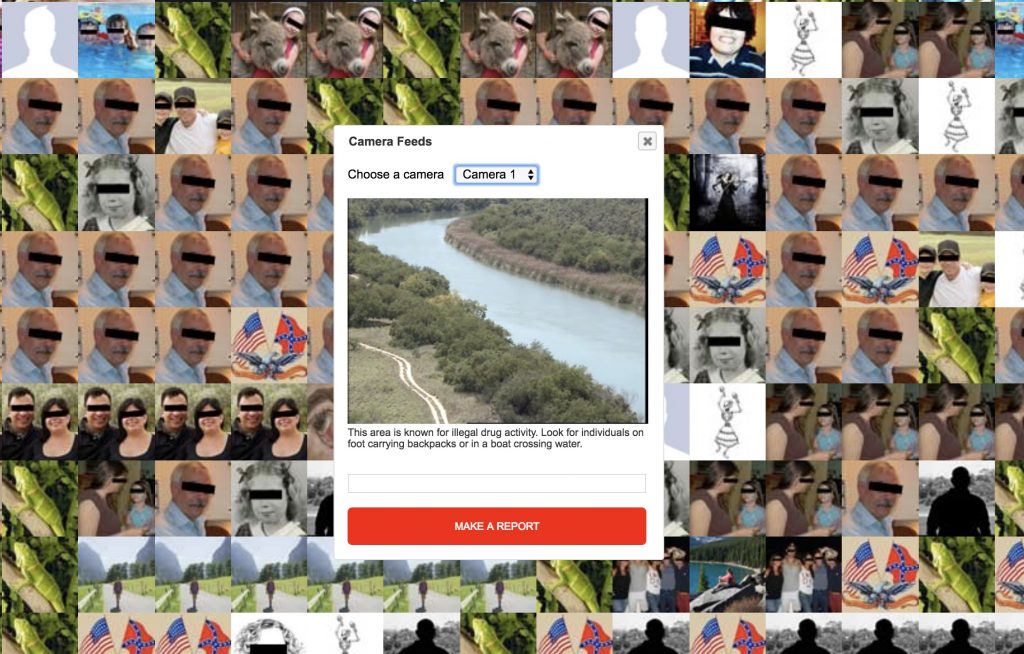

This project began in 2010, and looks critically at an online platform group, consisting of 203,633 volunteers surveilling the US-Mexico border, through a social media platform, such as Facebook. The community of The Virtual Watchers existed well before, and briefly, during, President Donald Trump’s signature promise in 2016 to build a wall at the US southern border, to stop more migrants crossing over onto US soil. The project also touches upon the wider online culture of attacks by bots and trolls from clandestine right-wing groups. The interview also explores Joana Moll’s interpretation of the Children of Prometheus exhibition, and briefly discusses other projects such as CO2GLE, which is an attempt to visualize how much carbon dioxide the company is emitting per second.

Interview

Marc Garrett: I remember when I first came across The Virtual Watchers, it left a deeply, unnerving impression on me. It reminded me of how threatening people can be towards others through the Internet. The project illustrates how participatory platforms which have come about, due to the rise of Web 2.0 culture; has not only paved the way for positive forms of mass communications for small groups and individuals to connect with each other, and with families and friends, but, there is also a darker side that people around the world have only in the last few years become aware of.

Out of the many scenarios you have witnessed when studying this virtual surveillance group, what has grabbed your attention the most, or feels most significant to you?

Joana Moll: The platform that gathered this group of people was specifically created to crowdsource national security by allowing citizens to monitor and report illegal activity in the us/mexico border. Ultimately the project shows how citizens can easily, and silently, be militarized by means of free labour, by translating a physical territory into social media, in this case, a border. Personally, what surprised me the most was the fact that most of the users we investigated, were either retired, unemployed or sick and couldn’t leave home.

The platform was a stage which allowed them to socialize and feel useful. A couple of users even claimed that the platform saved their lives, that their days became meaningful again. This use of the platform also revealed something important: according to the authorities, and this was that it was quite ineffective when it came to stop illegal activity around the border. Actually, some Sheriffs claimed that the amount of reports that they received on a daily basis were useless and difficult to process. However, the platform worked quite well in terms of keeping a large number of users monitoring the border. It had more than 200.000 registered users which spent more than 1 million hours securing the border for free.

Marc Garrett: This project and or artwork, has been around for nine years now. Yet, its subject matter was ahead of its time, and looking at it now it feels even more relevant. For example, across the world, the general public is only now coming to terms with the political and social, aspects and consequences behind the varied forms of virtual surveillance, dominating online interaction.

This is also true in regard to climate collapse, which brings me to your essay Deep Carbon (2018 ), where you say, the “amount of users and network connections has increased at a whooping pace ever since. In 2015, the Internet registered 966 Exabytes of IP traffic (1.037.234.601.984 GB) and is expected to reach 1579,2 Exabytes by 20182.”

And, then you say, “despite the growing number of Internet users and information flows, the material representation of the Internet and surveillance economy behind it remains blurred in the social imagination.”

What do you think will help to resolve the difficult issue in respect of material representation, in your terms?

Joana Moll: This is quite a difficult question to answer, indeed! I think there has to be a radical change in the way we produce and consume data, but most importantly, in the way our interfaces and interactions are designed. Even though our internet ecosystem is expansive we only interact with it through interfaces, and I really believe interfaces hold the key to start solving the problem. The energy consumption of most of our interactions in the digital realm are very opaque, we have no idea about all the processes that are taking place beyond the interface (i.e. a website, an app) and where all our data is going. I’m about to launch a project called The Hidden Life of an Amazon User which tries to bring to light all the amount of processes that are triggered by doing a simple purchase in Amazon. The amount of information that is involuntarily being loaded in the user’s browser is massive, let alone its energy consumption and environmental impact.

Since 2015, within the Critical Interface Politics group I founded at HANGAR (Barcelona), we’ve been developing experimental workshops that focus on developing sustainable interfaces. We usually work with a limited energy budget, which means that the interfaces we design can just use a certain amount of energy. It is really amazing how this seemingly small shift radically changes the way we think and design online interactions. If this would be a standard process when it comes to design our online experiences (which it should), would possibly have tremendous collateral positive consequences for the entire internet ecosystem, specially in terms of preventing to collect massive amounts of user data, which consume vast amount of resources. In this sense sustainable websites would be privacy friendly 😉

Marc Garrett: In what way do you think your own work fits into the context of the exhibition?

Joana Moll: It’s always hard to talk about my own work beyond my own work, but I’ll do my best! I feel my work tries to reveal very complex and hard to grasp techno-social arrangements in a very simple way. To allow people to understand the infrastructures and processes that govern their day to day lives without feeling smashed about their complexities it’s a central concern in my practice. I think my work fits in the exhibition in many ways, but I believe that this need to urgently discuss critical implications of our technologies with broader communities is one of the most relevant.

Marc Garrett: The postmodernist, feminist and theorist, Donna Haraway has recently re-emphasized the importance of re-evaluating certain contemporary contexts, especially those involving the patriarchy, politics, and climate change, in the age of the Anthropocene. I consider yourself, and myself, have been exploring our practices in parallel to Haraway’s critical ambitions, in respect that, we share similar values, but express them differently.

Thus, we need to re-examine our relationship with the world in the midst of spiraling ecological devastation, and find new ways to reconfigure our approach and connection to the earth and all its inhabitants.

Could you give us an example of your current works that you feel could be materializing Haraway’s writings, but as part of your own artistic production and or intention, and what the links and differences are?

Joana Moll: I agree, our work involves many of Haraway’s concerns, indeed. As for my practice, I believe politics, patriarchy, climate change and technology are continuously meeting and being questioned, in the sense that I always approach this contexts from different angles, which also talks a lot about my own process of understanding complex contemporary arrangements and how they affect and modify each other. For example, in my latest projects: The Dating Brokers and The Hidden Life of an Amazon User (HLAU), I examine how user activity, or in other words free labour, is heavily monetized by third parties. However in HLAU I also examine the energy costs that such exploitation is involuntarily assumed by the user. Graham Harman said it is very important no to assume that everything is connected, but to continuously trace the connections between things, which is something that I try to remember when I do a new project and I believe that Haraway’s body of work heavily points in that direction. However, I believe that techno-colonialism is a central issue to tackle while re-evaluating technology, politics, environment and most importantly, the way it affects and informs our ability to think and imagine. Together with my colleague Jara Rocha we’ve been recently collaborating in a series of projects and workshops that aim to reveal tangible outcomes of techno-colonialism in our daily lives.

Marc Garrett: The Children of Prometheus exhibition was mainly inspired by Mary Shelley. What elements in the exhibition’s: themes, ideas, and contexts, do you relate to personally?

Joana Moll: I relate to all of them, they are all so relevant and urgent! As for my work, I especially connect with the way invisible processes triggered by human-centered technologies affect our natural habitats. I believe that the exhibition opens highly relevant and urgent discussions about how society has been “Frankensteined” at large. The way our technologies are designed, produced and used are seriously damaging not just our life-giving habitats but also our relationship to them, our ability to imagine habitable ways to inhabit this planet.

Conclusion

When I first began the Children of Prometheus exhibition project, it was called Monsters of the Machine: Frankenstein in the 21s Century. Both titles fit the same curation function, and that is, to examine critically with other the artists in this touring show, Mary Shelley’s questions, that were asked in 1818, today, looking through her eyes.

I can’t imagine what she would think of Trump and all the other extreme right-wing, racist, groups and politicians, and dodgy corporations, exploiting people’s data, whilst adding to the destruction of the planet. However, in the spirit of Shelley, we have individuals such as Joana Moll who can play that role, with other artists doing what Shelley did so well then, but today. Our world is dying and those in power are part of non-friendly systems designed to kill it further, while the poor and oppressed take the brunt of it all. Moll, and the other Artists the exhibition, are presenting us with serious questions. But, accompanying these necessary and urgent concerns, are also answers at the same time. But there’s not much time.

Joana Moll is part of the touring exhibition, Children of Prometheus currently at the NeMe Arts Centre, Limassol, Cyprus 11 Oct – 20 Dec, 2019. This exhibition was originally produced in partnership with LABoral, in Gijon, and is an extension of the Monsters of the Machine: Frankenstein in the 21st Century, 18 Nov 2016 – 21 May 2017. We are currently negotiating other venues, in different countries across the world. Please contact if you’re interested in the exhibition.

Joana Moll will also be leading a workshop, THE INTERFACE, DECONSTRUCTED, and participating in a conversation with Tatiana Bazzichelli, founder of Disruption Network Lab as part of ACTIVATION: Collective Strategies to Expose Injustice, Saturday, 30 November 2019.

Artist Bio

Joana Moll is a Barcelona / Berlin based artist and researcher. Her work critically explores the way post-capitalist narratives affect the alphabetization of machines, humans and ecosystems. Her main research topics include Internet materiality, surveillance, social profiling and interfaces. She has lectured, performed and exhibited her work in different museums, art centers, universities, festivals and publications around the world. Furthermore she is the co-founder of the Critical Interface Politics Research Group at HANGAR [Barcelona] and co-founder of The Institute for the Advancement of Popular Automatisms. She is currently a visiting lecturer at Universität Potsdam and Escola Superior d’Art de Vic [Barcelona].

In thinking about the relationship between science fiction and social justice, a useful starting-point is the novel that many regard as the Ur-source for the genre: Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818). When Shelley’s anti-hero finally encounters his creation, the Creature admonishes Frankenstein for his abdication of responsibility:

I am thy creature, and I will be even mild and docile to my natural lord and king, if thou wilt also perform thy part, the which thou owest me. … I ought to be thy Adam, but I am rather the fallen angel, who thou drivest from joy for no misdeed. … I was benevolent and good; misery made me a fiend. Make me happy, and I shall again be virtuous.

Popularly misunderstood as a cautionary warning against playing God (a notion that Shelley only introduced in the preface to the 1831 edition), Frankenstein’s meaning is really captured in this passage. Shelley, influenced by the radical ideas of her parents, William Godwin and Mary Wollstonecraft, makes it clear that the Creature was born good and that his evil was the product only of his mistreatment. Echoing the social contract of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, the Creature insists that he will do good again if Frankenstein, for his part, does the same. Social justice for the unfortunate, the misshapen and the abused is what underlies the radicalism of Shelley’s novel. Frankenstein’s experiments give birth not only to a new species but also to a new concept of social responsibility, in which those with power are behoved to acknowledge, respect and support those without; a relationship that Frankenstein literally runs away from.

The theme of social justice, then, is there at the birth also of the sf genre. It looks backwards to the utopian tradition from Plato and Thomas More to the progressive movements that characterised Shelley’s Romantic age. And it looks forwards to how science fiction – as we would recognise it today – has imagined future and non-terrestial societies with all manner of different social, political and sexual arrangements.

Shelley’s motif of creator and created is one way of examining how modern sf has dramatized competing notions of social justice. Isaac Asimov’s I, Robot (1950) and, even more so, The Caves of Steel (1954) ask not only the question, ‘can a robot pass for human?’, but also more importantly, ‘what happens to humanity when robots supersede them?’. Within current anxieties surrounding AI, Asimov’s stories are experiencing a revival of interest. One possible solution to the latter question is the policing of the boundaries between human and machine. This grey area is explored through use of the Voigt-Kampff Test, which measures the subject’s empathetic understanding, in Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (1968) and memorably dramatized in Ridley Scott’s film version, Blade Runner (1982). In William Gibson’s novel, Neuromancer (1984), and the Japanese anime Ghost in the Shell (1995), branches of both the military and the police are marshalled to prevent AIs gaining the equivalent of human consciousness.

Running parallel with Asimov’s robot stories, Cordwainer Smith published the tales that comprised ‘the Instrumentality of Mankind’, collected posthumously as The Rediscovery of Man (1993). A key element involves the Underpeople, genetically modified animals who serve the needs of their seemingly godlike masters, and whose journey towards emancipation is conveyed through the stories. It is surely no coincidence that both Asimov and Smith were writing against the backdrop of the Civil Rights Movement, but it is also indicative of the magazine culture of the period that both had to write allegorically. In N.K. Jemisin’s Broken Earth trilogy (2015-7), an unprecedented winner of three successive Hugo Awards, the racial subtext to the struggle between ‘normals’ and post-humans is made explicit.

Jemisin, like Ann Leckie’s multiple award-winning Ancillary Justice (2013), is indebted to the black and female authors who came before her. In particular, the influence of Octavia Butler, as indicated by the anthology of new writing, Octavia’s Brood (2015), has grown immeasurably since her premature death in 2006. Butler’s abiding preoccupation was with the compromises that the powerless would have to make with the powerful simply in order to survive. Her final sf novels, Parable of the Talents (1993) and Parable of the Sower (1998), tentatively posit a more utopian vision. This hard-won prospect owes something to both Joanna Russ’s no-nonsense ideal of Whileaway in The Female Man (1975) as well as the ‘ambiguous utopia’ of Ursula Le Guin’s The Dispossessed (1974). Leckie, in particular, has acknowledged her debt to Le Guin, but whilst most attention has been paid to the representation of non-binary sexualities in both the Ancillary novels and Le Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness (1969), what binds both authors is their anarchic sense of individualism and communitarianism.

Whilst sf has, like many of its recent award-winning recipients, diversified over the decades, there is little sense of it having abandoned the Creature’s plaintive plea in Frankenstein: ‘I am malicious because I am miserable.’ It is the imaginative reiteration of this plea that makes sf into a viable form for speculating upon the future bases of citizenship and social justice.

As curator of the exhibition Monsters of the machine: Frankenstein in the 21st Century, I thought it necessary to interview the artists in the exhibition, while it is shown in the magnificent gallery space at Laboral, in Spain, until August 31st 2017. I wanted to get more of an idea of how they see their work in the show relates to the core themes. Mary Shelley’s book Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus, has been interpreted in numerous ways since was written in 1816, and then published anonymously in London in 1818.

Eugenio Tisselli is a Mexican artist and programmer. He is a PhD candidate at Z-Node, the Zurich Node of the Planetary Collegium. Previously, he worked as an associate researcher at the Sony Computer Science Lab in Paris and was also a teacher and co-director of the Masters in Digital Arts program at the Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona. In his role as director of the ojoVoz project, he has carried out extended workshops with small-scale farming communities in different parts of the world. The ojoVoz project may be accessed at http://ojovoz.net. His personal projects may be accessed at http://motorhueso.net

Marc Garrett: Can you explain how and why the Sauti ya wakulima, “The voice of the farmers” project came about?

Eugenio Tisselli: In 2010, I came to realize that the way we feed ourselves is actually one of the main drivers of the accelerated destruction of societies and ecosystems that is currently underway. I felt like I had been living in La-La-Land before the veil was ripped off. My life changed radically. At that time, I was collaborating in the megafone.net project which had worked since 2004 with several groups of people at risk of social exclusion in different parts of the world. By offering an unfiltered communications platform, consisting of mobile and web applications, the megafone project tried to help these groups to make their voices widely heard. But, in 2011, I left the project with the purpose of offering its tools and methodologies to farming communities who wished to seek recognition and explore different forms of communication.

The first opportunity took shape in Bagamoyo, Tanzania, where a group of farmers expressed their interest in trying out these tools. I came in contact with this group through a scientific project that studied the direct and indirect effects of climate change on agriculture. The original goal of ‘Sauti ya wakulima’ was that the farmers would use smartphones and a web application to create a collaborative, audiovisual knowledge base of weather-related events, such as droughts, floods or crop diseases. However, the farmers eventually discovered that they could reshape this goal, and started to use the phones to interview other farmers with the purpose of creating a network of mutual exchange of knowledge about agricultural practices and techniques.

Episodes of fruitful learning have happened since then: one farmer learned the proper way to grow maize thanks to a picture taken by one of his colleagues. Another one learned a clever way to build chicken sheds during a trip to an agricultural fair. He took pictures of the sheds and when he came back to his community, he formed a cooperative for chicken production together with three of his colleagues. I could go on, but the project is still active after six years and that is probably the best thing that can be said of ‘Sauti ya wakulima’. It is alive because farmers find it useful, and it’s inspiring to learn from them that the mutual exchange of knowledge can become a key to a more resilient and interesting life. To me, the agricultures depicted in the photos posted by the Tanzanian farmers are not echoes of ‘the past’, but pathways to the future.

MG: What particular themes in the exhibition do you feel relate to the “The voice of the farmers” installation?

ET: I imagine ‘The monster in the machine’ not as a horrible, threatening ghoul, but as a weird and tricky creature made of language. The ‘body’ of this creature is made up of what we would call ‘principles’, ‘values’ and even ‘ideologies’. And it silently lurks inside the technological artifacts we use every day. The smartphone, for instance, epitomizes the ideal 21st century citizen: a self-sufficient, competitive and efficient individual. And, indeed, the monster that lives inside our smartphones is made of those values: its presence is inscribed in the device’s circuits and from there it casts its spell. What I mean is that technologies are not neutral. They are not empty: they are haunted by whispering ghosts.

If you look at technologies used in agriculture, you will also find a multitude of monsters that softly dictate from the insides of things. Perhaps not by coincidence, genetically modified (GM) seeds speak the same things as mobile phones, only with different words. They tell farmers: “stop sharing seeds with your community, it’s a waste. Become an entrepreneur, there are shitloads of money to be made! Buy me! I’ll make you rich!” The sad thing is that these words are a trap: farmers ultimately become entangled in monetized loops that are beyond their control. Desperation sets in and, in absurdly horrible cases, such as GM cotton farmers in India, suicide becomes the only exit. But there are, indeed, other exits.

It is possible to rewrite the values and ideologies inscribed in technologies, in order to make them speak words that will do less harm. This is one of the key components of Sauti ya wakulima. From the very beginning of the project, the farmers agreed to redefine the smartphones as communal tools for collaborative documentation. They still share them and, when it is someone’s turn to use one, that person knows that she will not be taking pictures and recording sounds with a personal device, but with one that belongs to the group. These dynamics of sharing can create or strengthen reciprocal bonds. Renalda Msaki, a farmer who participates in Sauti ya wakulima, once said that the project had brought the group closer together. When I reflect upon her words, I can see how the monster in the machine can be transformed into a gentler creature that, nevertheless, remains weird and tricky.

MG: What role do you think the artist has when dealing with questions such as Monsters of the Machine exhibition?

ET: I think the artist can take up an incredibly vast range of roles when dealing with machines. But, whatever one does, one shouldn’t be naive about technology. Happily, the times when media artists created huge and complex pieces filled with little technological wonders just because it was exciting to celebrate their ‘magic’ is (almost) over. I used to say that (most) media art was the smiling face of techno-capitalism. Now I would add that, while technology was generally understood as a mediator between us and the world, it has now become a vector that uses humans to create its own mediations with the world. The roles have shifted, and things have taken a perverse turn. There’s a growing chorus of techno-objects that insistently asks us, humans, to drill the Arctic, build pipelines, burn coal, destroy forests and dig up more minerals. And we obey: we must feed the monster. Artists who approach technologies as materials to play with need to be aware of these power relations. We must acknowledge that technologies of all sorts have become overpowering actors that like to command.

Tisselli warns us that we need to be more aware of our responsibilties when implementing technologies into the environment. An important factor of the exhibition was to bring about a vision where the art was not just one type of art. This means different engagements in how we see and work with technology, are reflected as part of its context. Also, technology is not only a human skill, ’21st century scientific studies indicate that other primates and certain dolphin communities have developed simple tools and passed their knowledge to other generations.'[2]

As I write this conclusion, ‘Trump is poised to sign an executive order that will dramatically reduce the role that climate change has in governmental decision-making. The order could impact everything from energy policy to appliance standards.'[3] We live in a time where US policies are written via Twitter, and the rich are typically risking ours and the world’s future for their own ends. Tisselli and the farmers, remind us that, we need to be connecting with the land once more. We need to reclaim the soil before it is lost forever.

Mary Shelley’s distrust of the patriarch in the form of Dr. Victor Frankenstein, is as relevant now as it was 200 years ago. ‘Her portrayal of Dr. Frankenstein as an egocentric obsessive who will stop at nothing until he completes his mission in bringing his creature to life; represents man’s blind quest in pushing on until the precarious end, at whatever cost.'[4] Tisselli echoes this with his own critique towards artists working in technology. If we are to rethink what innovation can be now, what would that look like if we were to update it in a way that included indigenous voices, other levels of equality, and practices beyond what now seems like tired, machismo, and over obsessive, tech-enchantment?

The ‘Monsters of the machine: Frankenstein in the 21st Century’ exhibition is on at at Laboral, in Spain until August 31st 2017. http://www.laboralcentrodearte.org/en/exposiciones/monsters-of-the-machine

Those involved in the Sauti ya wakulima / The voice of the farmers project.

The farmers: Abdallah Jumanne, Mwinyimvua Mohamedi, Fatuma Ngomero, Rehema Maganga, Haeshi Shabani, Renada Msaki, Hamisi Rajabu, Ali Isha Salum, Imani Mlooka, Sina

Rafael.

Group coordinator / extension officer: Mr. Hamza S. Suleyman

Scientific advisors: Dr. Angelika Hilbeck (ETHZ), Dr. Flora Ismail (UDSM)

Programming: Eugenio Tisselli, Lluís Gómez

Translation: Cecilia Leweri

Graphic design: Joana Moll, Eugenio Tisselli

Project by: Eugenio Tisselli, Angelika Hilbeck, Juanita Schläpfer-Miller

Sponsored by The North-South Center, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology – Zürich

With the support of The Department of Botany, University of Dar es Salaam (UDSM)

Featured image: Jane and Louise Wilson – ‘False Positive, False Negative’ (2012 Screen print on mirrored acrylic)

The Negligent Eye the Bluecoat Liverpool Sat, 08 Mar 2014 – Sun, 15 Jun 2014 http://www.thebluecoat.org.uk/events/view/exhibitions/1971

Featuring artists: Cory Arcangel, Christiane Baumgartner, Thomas Bewick, Jyll Bradley, Maurice Carlin, Helen Chadwick, Susan Collins, Conroy/Sanderson, Nicky Coutts, Elizabeth Gossling, Beatrice Haines, Juneau Projects, Laura Maloney, Bob Matthews, London Fieldworks (with the participation of Gustav Metzger), Marilène Oliver, Flora Parrott, South Atlantic Souvenirs, Imogen Stidworthy, Jo Stockham, Wolfgang Tillmans, Alessa Tinne, Michael Wegerer, Rachel Whiteread, Jane and Louise Wilson.

The Negligent Eye revolves around the way a digitally-native generation of artists – particularly printmakers – are questioning their relation to the digital, using the notion of ‘scanning’ as a kind of mid-state of the creative process of the human-digital hybrid. The show is co-curated curated by the Bluecoat’s Sara-Jayne Parsons and head of printmaking at the RCA, Jo Stockham, and features several works by her graduates, and other artists from around the RCA, such as Bob Matthews and Christiane Baumgartner. “The relationship between the material and virtual worlds is a question, a set of contradictions we are all inside and how technical images exert their influence on our everyday experience is of ever increasing importance.” Jo Stockham.

In her article Too Much World: Is the Internet Dead? Hito Steyerl asks what happened to the internet, after it died – that is, in an era of the “post-internet” after it stopped becoming a possibility, even in the midst, because of, and symptomized by, its permeation of everything. Steyerl is a major force in understanding our relationship to digital images, and her use of ‘death’ occurred to me often during viewings of this show and surrounding events, particularly as it could be applied to the post-digital.

So in a sense, I experienced the show as an autopsy of the digital image. From the tragic, simian face looking out from the first ever digital image, taken by Russell Kirsch of his son in 1950, exhibited at two points in the exhibition like an insistent memory. To Marilène Oliver’s figures from her 2003 Family Portrait series where bodies have been evoked as series of horizontal cross-section prints layered on acetate, so that they appear as though stored, but only partially in this world; the exhibition continually references, exemplifies and unpacks the death of its medium.

The post-digital is a paradoxical term – at once assuming the reliance of all contemporary culture in digitality, but also looking past it; affirming the death of a form, while embodying its afterlife. This is what Elizabeth Gossling’s images of a dead comedian says to me, when it is scanned from a computer screen and printed back on to archival paper, with his image waving from behind an ether of static, living in the solid pulp. The best works in this show, Gossling’s included, speak very eloquently about the post-digital, and how artists are motivated into hybrid forms of production, always acknowledging and working in a context of the saturation of the digital.

The notion of saturation, and its implications of the dissolution and liquidity, itself saturates the show: the first work, Maurice Carlin’s monumental print, scrolling down from the ceiling of the vide space is in one sense a spectral ancestor of Monet’s waterlilies, but with gashes and pustules of CMYK colour oozing up from behind the serine blue and greens of the pond, and white pixel-like rectangles plugging up the gaps; London Fieldworks’ 3D image of data collected from Gustav Metzger’s brain while he thought of nothing, is presented on a screen with a trickling sound – perhaps of information leaking inexorably back in?

Marilène Oliver’s glitch-sculpture of body parts fused in the heart of the 3D scan/print machine hang in the chute of the gallery corridor, their surfaces mid-ripple as though submerged; Jo Stockham’s etherized black and white shot of an element of the London skyline, seen perhaps through a teary bus window, but now writhing with red in its afterlife as a veined and depthless skin.

Using damage and error to expose the affectivity of a medium, particularly in the context of the digital is the central mode of Glitch Art. I have already used the term glitch to describe the aesthetic of Marilène Oliver’s sculptures, and the traces of digital-to-digital scan in Gosling’s work and the rich material pixilation of Christine Baumgarner’s inscription of CCTV camera stills into largescale wood prints, also contain these signatures.

If there is a criticism to be leveled at these admirable and, frankly gorgeous, works. It is in their distance from what Rosa Menkman refers to as the moment(um) of the glitch. In the medium of print-making, the material fact of the object dominates, and with this show, no-matter the stated and playful interest in the ‘between-state’ of scanning, there remains the focus on material production – and therefore an irrefutable commodification.

Prints on archival paper and tempered steel, casts in plaster and large-scale hardwearing plastics, each speak of an appropriation of the tactical and fluid glitch, and its migration into commodifiable form. Maurice Carlin’s large-scale printwork could adorn a restaurant wall, just as Monet’s waterlilies functioned during his era, and Oliver’s sculptures also speak and modernise the language of sculpture as produced for private collections through the ages.

There are works also which say nothing of the ‘post-digital’, such as Imogen Stidworthy’s Sacha, a deeply thoughtful study of a wire-tap transcription ‘artist’ Sacha van Loo. Stidworthy’s enigmatic works are often hard to pin down thematically, and here it feels like the loft-type space of Gallery 3 has been used as an outer limit to the reach of the show. And then there are other works that say nothing at all and lessen the show’s conceptual rigor. I see Jeaneu Project’s peice, and think ‘smudge lawn’. I see a Cory Archangel print and a Rachel Whitereed miniture and their names flash through my consciousness like a Google Glass press release.

Truly though, this is a really refreshingly vibrant and precient show at the Bluecoat, and a great partner to the Mark Lecky exhibition featured at the venue last year in its pressing contemporaneity. The exhibition has also been a fulcrum for a really interesting series of events which have dealt with image production – including a day of talks and presentations, i-Scan, artist talks from contributing artists such as Imogen Stidworthy, and independently curated events such as the second in Deep Hedonia’s excellent Space/Sound series, where artists such as Madeline Hall, Jon Baraclough, Simon Jones and Andy Hunt explored the multiple angles from which digital scanning can be exploited as a performance and av medium. As with the Mark Lecky show, there is something about the context of the Bluecoat, as Liverpool’s most paradoxical space, which delivers an archival retrospective out of the most up-to-date material, and this tension is what pulls appart the body of works before us.

The Rubik’s Cube is not just a forgotten toy from the 80’s. The fact is that it’s even more popular than ever before. You can play with this great puzzle here.