This is the third of three pieces on people who are posting work to the photography sharing site Flickr [1].

In this final article I look at the work of Karin Rudolph

. Rudolph is a Belgian photographer, currently living in Athens, where she works as a wedding and event photographer and raises two teenage sons. In addition to her work for pay she makes an ongoing series of ‘personal’ images which she regularly posts to the photo sharing site Flickr.

I ask her to send me some images from a wedding job and she does.

It is a job she is clearly good at—everything is beautifully shot, nicely framed, sharply in focus (when sharp focus might be thought necessary), but there is that extra something that comes with a good portrait photographer, which I can only describe as fellow feeling. A fellow feeling which elicits transparency and a willingness to risk vulnerability from the subject. I’ve never met Rudolph but it’s clear that her personality, her way of being, is a player here.

There’s also a sharp curiosity at work—a hunger for the way the world looks and with Rudolph this seems to become attached to particular objects, creatures (some human, some not) and roles. There was a dog at the wedding in the images she sent me. The wedding took place outdoors and the clearly much loved animal figures in a number of the shots. It’s as if at one point R becomes fascinated by it and we get shots where the all humans are cropped (in the shooting; she doesn’t crop after the fact) down to the waist and the dog becomes central (although a small child has a supporting role here too since he necessarily evades the crop/frame wholesale). We get a dog narrative. Then a bouquet catches her eye and we get a bouquet narrative, the wedding filtered through a non-human being or an object. Motion—a sense of the moment before and the moment after being necessary, if hidden, components of this still image—is a key underpinning of so many of these images, particularly in relation to these micro-narratives.

In a photographer less manifestly gripped by the facts of our fragile human being and ways in the world one might call some of her approaches formalist. It is certainly true that rhyme, echo, geometry, continuities and disruptions of line, shape and colour play a highly significant role in the structuring of her images but one of the driving forces of R’s work is that it constantly moves to dissolve any artificial divide between content and form. Yes, her eyes seek pattern; yes, this or that organising device might order an image but this never obscures our awareness of the facts, feelings and relationships portrayed or implicit there. Also—we humans are formalists, aren’t we? We’re pattern seekers. We play. Were you never fascinated as a child by mirrors, by the world turned upside down by hanging from your legs or by the cropping or heightening, or focus) achieved by looking through the cracks in your fingers? Of course you were. As we grow we perceive the whole world through a complex dialectic of what is presented to our senses on the one hand and our burgeoning sorting and structuring principles on the other. We are of necessity creatures of content and form together and one surmises that this is what makes us creatures of art too.

I’d been writing and thinking about this piece for a few months, on and off, and I’d got to a second or third draft when it hit me with a thud, a jolt, that hardly any of the recent images have titles.

The fact had just sailed under my radar, curiously, since I’ve argued and will again, that insofar as we can talk about meaning in a photo (or any visual artwork) this possibility lies in a network of references and comparisons which ineluctably involves talk, writing or both. Language. Further, that visual art is best seen as something humans do (emphasis on both words) than as the usual set of isolable ‘in and of themselves’ objects (which isolation is a fiction, at best an analytical convenience). And then it struck me ( I was being struck a lot that day) that there is something about these images that fights back against language—they’re often cross genre and resist categorisation and there’s a sense in which the easiest approach to what’s in them is simply to list it, and finally to say that this image had these things in it under this kind of light from that angle but, of course, this is far from satisfactory and at root there is something far transcending taxonomy or description going on. But –dammit! –I can’t help feeling it is as if the images (placed as they are in the sequence formed by Flickr) are calling out, hailing each other. I don’t know why, but forced rhubarb, a most unlikely image, is the one which springs to mind and persists, as if the absence of the immediately adjacent language of a title somehow forces the set of glorious but hitherto mute images to invent speech.

Anyone who has ever taken an un-posed image of a human being on a fast shutter speed will be cautious about ascribing emotions or characteristics to the subject on the basis of what is revealed. As in so many other ways, the very small, the very distant or unreachable, animal locomotion, the photograph reveals things beyond our normal ability to see or grasp them. One of these things is the curious plasticity of the human expression and how in our interactions we read this in sequence, in time, together with a host of other clues, aural and visual, to make sense of what is going on, to try to understand both what a person is doing and to surmise what they might be feeling . (Of course the opposite of this, the posed image, brings its own problems too.)

When we think hard and soberly we cannot but be convinced that the photograph alone, an impossibly small fragment of time, does not allow us enough evidence, that it is somehow unanchored in the world.

And yet, the desire to draw conclusions, to make comment, is certainly strong in us and each photographic image of a person, especially the striking and affecting ones, comes with a very strong sense that we are able to do so.

What can we actually say about the still photographic portrait, both in general and in particular cases?

One thing we might say is that the single image’s apparently complete account of a human being, based upon a fleeting expression (and perhaps the fleeting expressions in response of others and maybe also the presence of contextualising objects or other clues) suggests at best, a class of possibilities. This single image evokes a range of other possible images and moments in the world at least one of which must correspond to our strong intuitions about it. So even if we were able to establish the facts of the matter in this particular case and it made a lie of our emotional response , nevertheless that response represents a truth and somewhere, perhaps quite often, in the world, situations occur, have occurred, will occur, which correspond to this truth.

And it seems to me that it is this instinct for general human truth, allied to the particularity of light, line, composition, of other things depicted, which manifests in the eye-and-heart-catching-ness of the resulting final image.

A strong way of putting it would be that any portrait is just as much a work of fiction as a novel but that as we would not wish to deny something called ‘truth’ in the novel ( you might—I see no point to the thing otherwise) in the portrait we work our way back to truth.

And at least for me it is the photographer’s—and here, now ‘the photographer’s’ means R’s—capacity for empathy, for narrative, for understanding of the world and the wonder and the oddness of its inhabitants that makes her such a good portraitist (and let’s not forget, too, simply having done the thing a lot —this is often underrated nowadays.)

Do I know whether the Orthodox priest at the wedding table was a kind man? No. I don’t. I cannot. Is kindness manifest in the photo, is the possibility of kindness in the world reasonably asserted in it? Do I know more about kindness thereby? Absolutely.

There’s a black and white image, taken, I think, at the place where her teenage sons practice their footballing skills which feels like a short story or perhaps a collection of short stories, each cued by the various human presences which form at one and the same time a large (in how they capture our attention) and a small (in how much actual area of the image they occupy) part of the entire image.

It also has a most clearly defined geometry—three strips, the topmost being the practice field itself, the middle appearing to be a road like depression running between the photographer and this field and the lowest a pavement of some sort on the other side of that ‘road’. The almost bizarrely long evening shadows of R and a companion (and the horizontal distance between shadows is nicely ambiguous on the exact relationship between those shadowed) stretch forward into the image. The vertical grid adjacent to them, with a gap in the centre picked out in shadow too, suggests they are standing at a pedestrian gate to the place. I imagine the figure at the viewer’s right is R as the arms appear to be raised in a photo taking action.

(The image thumbs its nose at genre—it is oblique self-portrait, landscape, social history, portrait and exploration of geometry and structure all at the same time.)

Shadows aside, the figures which catch my eye (what about you, so much to choose from or are you constrained in a similar way to me by something in the way the image is structured?) are the short stocky man in motion, walking away from us at the image’s far right top strip foreground. There’s a delicious swagger and confident openness about him.

Has he passed through the gate where R stands? Did he greet her?

The second key (perhaps because nearest?) figure is the young man, top strip, viewer’s far left, again in movement, this time almost certainly certainly sports related. Is he pursuing a stray ball? Running to greet a friend? Engaged in some sort of running warm up/exercise? As we strain to see, our relationship to the image’s scale shifts and we begin to realise just how many other figures he opens up to us—there are at least six either standing or seated in those little sheds at the field’s side between him and the left edge of the nearest goal net—each an enigma of a small but definite kind—and when we move rightwards from them we realise (and we have to move closer in, look differently, at the image to see this) just how many people there are in some sort of action here. As we move out again we are stuck by the contrast between the contemplative calm of the giant shadows and the anthill busyness of the young men. And here’s another thing. This is such a male photo. (With the exception of the photographer and I think it’s only because I know she is female that I read her as such. Then even as I write this I notice the slight head-cocked-to-one-side quality of aficionado-like attention in the head of the left shadow—and why do I think that might clue maleness? What does that say about me?) Oh! Layers and layers of fact, of presence, of things to enumerate and puzzle over. So much! And this before we take the thing as a totality—geometry, inhabitants, shadows, activity, motivation, time of day, distant trees, weeds and barren ground, a sky whose colour we can only guess from the fact we know there is evening sun. And that totality is the hardest thing to compass in any way other than an intake of breath or shiver down the spine. Enumerating the contents helps (although it’s not essential to the immediate affective apprehension of the whole—that just happens) but it’s the inexplicable (not a value judgement—literally inexplicable—simply, ‘This is what R did’) decision to frame those contents in that way—the bit of the process which defies words—that makes this and so many other pieces by her so powerful.

5.

A ravenous eye.

She has a ravenous eye, constantly tracking the scene in front of her and hungry for detail. This hunger does not distinguish between content and form. Whatever is human, whatever stirs affect or curiosity—whether pattern, rhyme or echo, or ethics, or suggested human warmth or frailty, this is swallowed up and processed by heart and mind in turn

The resulting images bear the strong feel of certain, almost objective, structuring principles—that following of object or creature within a scene, the use of rhyme and echo. Two further categories are geometry and colour (and nothing here is pure, there are no essences, sometimes blocks of colour impose an extra, parallel geometry upon a scene whose first order sense—whether it be human beings in action or traces of interpretable human activity; buildings, signs, the street —apparently lies elsewhere.) The key thing about all these structuring principles is that they are found, excavated, discovered, seen—not made. They happen in parallel with, arise out of the actions and feelings of, human beings in this world, the only one we have.

Because she is someone who has lived, fully, in that world, for a fair time, because her hunger extends beyond the visual (she always has a book on the go and the range of these is impressive), because she has a number of languages and is at home in at least three cultures, she makes images which are connected and re-connected by hundreds of threads to things we ourselves might have read and thought or experienced and talked about. Further, it is impossible to imagine that the fact she is a woman living in a country not of her birth, where she has learned a different script, different ways of talking and being, where she works in part as an image maker for hire and constantly both connects and holds separate that work for pay from own ‘own’ work, at the same time as raising children by herself, that these facts are not also somehow foundational.

For a long time I have struggled with how to attach the word meaning to image. It is too easily and glibly used. An image never ‘means’ a single thing (unless it is the poorest of images and even then the human capacity for/delight in ambiguity sets to work to disrupt this) What is evident in Rudolph’s work is networks of evoked meaning, memories, feelings.

Her way of being in the world, this following her eye and nose, means that there is a kind of metonymy purged of any attempt at system—here is a dog or child or chair or window. Here are the things which necessarily were near it at a moment in time and this is how they were disposed. There was reason and there was randomness. Parts of the disposition were beautiful. (What do I mean by beautiful? They move me, they fill me with a joy that cannot be reduced to words though it perhaps can be limned by various combinations of words, combinations potentially infinite which always nearly but not completely fail.) Parts of the disposition were stark or threatening or at least worrisome. The bringing together of all these parts—worry, beauty, pattern, action—into an image framed, bounded, lit, by the laws of the heart and the laws of the intellect now pulling one way, now the other. The work about the world is itself part of the world. We are not alone. No person is an island. We can read each other’s thoughts. We can feel each other’s feelings.

The words and the image and human heart and human history dance ever outwards and outwards. What does an artist do but always start to write the whole history of humanity in the world?

In the second of three articles about the Web 2.0 photosharing service Flickr (the first is here), I continue to make a case for the quiet but profound innovations created by the sheer scale and ease of use, of these services – something which enables self defining artist, outsider artist, hobbyist & people who would run a mile from being called an artist to share and be mutually influenced by each others work. Here I offer some notes on the beautiful, funny and humane photography of London art teacher Joseph Cartwright, who operates under the Flickr name Noitsawasp.

Very few humans directly in these images but everywhere traces, evidence of human activity. Not cold. Full of humour.

Patterns of human activity, some accidental but capable of being invested with new meaning. Some straightforwardly meaningful, interpretable. Evidence of events and activities.

Always formally engaging.

A map of a world. A map of our world. A map of the world of work, of most of us, of the 99%.

Impossible to imagine these images made on streets of a town where less than 50 languages were spoken.

What we see when we look at these is what we see when we look at art.

An invitation to narrative.

Patterns on the one hand // traces of the wake that humans leave behind them in the world.

One of those humans is Joseph C––sometimes the images are records of his interventions in the world of images––those image fold-overs or blends. Sometimes the photos are a record of him as performer, actor, in the world ( but after he has left the stage). Sometimes they seem to place us directly behind his eyes.

I think he looks quizzically at the world. Do you know him––does he look quizzically at the world?

You imagine his eyes darting around––down, to the side, up occasionally, lighting on something, some congruence of objects, pausing to decide whether to make an image…(brows knotted, a sense of pressure, the need to seize the moment…)

look at this; see through this; look into that; make that out

grids; grids; patches of light; a dictionary of cowboy terms

People nail nails, people mend things, people bend things, people break things, people clean, people wash clothes, people read, people admonish, people alert, people have funny feelings––goose bumps, shivers or feelings it’s hard to explain somehow.

I saw a pattern! It was a message to me! It was a message to you. It made me feel…oh…I can’t say what…

This empty table here; those empty chairs there

The café/condiment photos––a series––eating––so basic––and we always remember that but we also think––‘we know this kind of café too’, ‘we go here on these occasions’––and we wonder what kind of a person this serial café goer is, is this an important routine in his life, does it define him amongst others, his friends, colleagues, what does he eat, are the condiments incidental or fundamental to his café visits, does he keep his distance from the condiments, use them with discretion, does he go to the café now only or mainly for his mission to image the condiments or do his meals and his art dovetail nicely, conveniently, pleasantly here. Do his companions laugh when he takes today’s photo? Or does he eat alone?

Cables, pipes, tangles––runes, ciphers, hieroglyphs.

The morning was sunny. It rained. The afternoon was still warm but muggy. There was a rainbow. The sky was blue. The fence was a different blue.

Shadows, folds, stripes, other repetitive patterns. Some there, pre-intended, functional. Some found, loaned, in the process of making the photo.

Objects that are (or have been) useful or functional removed from or seen out of their usual context. (Sometimes by human agency––dumped, temporarily abandoned, or simply cropped)

Estrangement––making us see the world anew // making us remember our world anew.

Found patterns, found juxtapositions.

A lively eye and a lively mind.

Joy in colour. Grace in handling, in apportioning that colour. It’s like he finds the best tidbits and, smiling, hands them to us.

It isn’t abstracting from the world // the function is often still evident so it’s like layer upon layer of meaning and affect and confusion // the original function or action…the strange pattern it makes… its removal from its usual context.

These images lend us Joseph C’s eyes. These images lend us another human’s mind and sensibility.

When you are a child and you’re walking along by the side of a grown-up and they have important things to do or say and so you are free to look around and feel and think and wonder and also you are half their height or less so you have both the utter freedom to look where you will and you lack preconceptions about what it is you see signifies or how it ought to make you feel and on top of that you see it from an angle that will never again be natural to you without a degree of contortion. And you are become magically a kind of still, observing, feeling centre of the world.

Joseph C gives us back some of that.

‘I love kitsch. I adore bad taste. I fall for the maladroit.‘ – Andrea Judit Tiringer

In a recent book ‘What Photography Is’ – and just what it is seems to be akin to the meaning of a word for Humpty Dumpty – “just what I choose it to mean – neither more nor less” – the critic and theorist James Elkins savagely lays into the users of the photography sharing site Flickr. There’s a page or so of magisterial denunciation delivered in a scornful tone not unlike Humpty Dumpty’s: “Nothing is more amazing than Flickr for the first half hour, then nothing is more tedious” and “…each group puts its favoured technology to the most kitschy imaginable uses”.

1.

It’s not that Elkins hasn’t hit on something – all the sins he bemoans, and more, certainly exist on Flickr but his is a superficial, lazy and tendentious view which evinces a shocking lack of curiosity and imagination for one so exalted in art academia. (Indeed so incensed did Elkins’s tirade make me that I started a Flickr group entitled Bollocks to James Elkins: https://www.flickr.com/groups/bollocks_to_james_elkins/rules/ please consider joining if you’re active on Flickr.)

Flickr gets lambasted too, from the opposite perspective to Elkins, by the proponents of a kind of “bottom up”, “anti-elitist”, account of art, by those who dislike its corporate ownership and by those, too, who believe that one should build such communities with pure free and open source software. To be fair to them there is here, too, much to agree with; Yahoo, Flickr’s current owners, are clearly more interested in maximising advertising income than the welfare of their users.

And yet, and yet… a little looking, a little thought and, hardest of all it seems, a little intellectual humility reveal – perhaps only the embryonic stage of – something rather marvellous too. The sheer scale of the network of users (which one must point out here could only be a utopian hope for an alternative network, at least under the current social and economic system), the fact that it is impossible that the art world as it currently exists can (or might want to) present to us every piece (or even a small percentage) of work worthy of our attention and, further, that there are many people for whom the impetus to make work is a stronger imperative than getting on in life, or becoming celebrities or making money – akin to Marx’s “Milton [who] produced Paradise Lost in the way that a silkworm produces silk, as the expression of his own nature” – means that careful sifting reveals artists every bit as worthy of our attention as those who please the art-world gatekeepers.

I’ve found hanging out on Flickr enormously nourishing both in terms of intelligent feedback on my own work but also in terms of the diversity of interesting and engaging work by others, some of whom even employ the “favoured technologies” – which largely seems to mean software manipulation – Elkins finds so risible, but in such a way that any honest accounting would find far from such.

It is true that one is tempted on occasion to conceptualise some of this work in terms of “outsiderdom” and this can be a helpful starting point; but there is a quantity/quality dialectic at work in the sheer size of the Flickr database and in the dialogues between the highly focussed outsider, the odd art world figure who doesn’t fear to rub shoulders with those not in the charmed circle, the family snapshot taker and even, though admittedly rarely, the amateur photographer who takes “well-made” photos but doesn’t forget to make them interesting too. There is a wider point contra Elkins here which can be expressed succinctly as – no form, no technique is in and of itself ruled out from the process of making art. Indeed the greatest artists have often taken the lowly, despised and out of fashion and given it a magic twist to create previously undreamed of possibilities.

I venture to suggest that the beginnings of something qualitatively new are here stirring.

That’s a long preamble to some showing, rather than telling. I want to look at a single and in my view very interesting participant on Flickr. First to introduce her work and then talk to her about what it means to her to make and post it.

2.

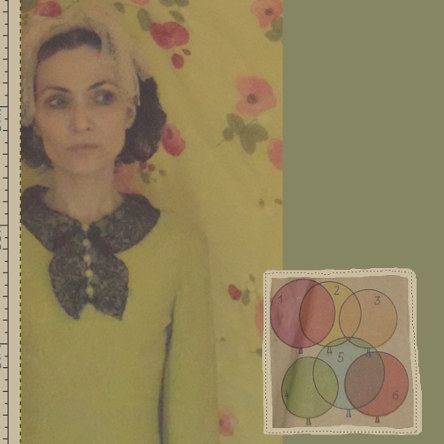

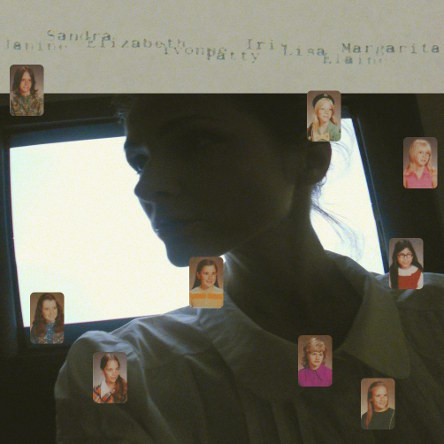

nem sáℜa (Hungarian – ‘not Sara’ – the odd typography for the ‘R’ is a personal quirk and not a language feature ) is the name under which Andrea Judit Tiringer posts work to Flickr. Her body of work is at the same time highly consistent and extraordinarily varied. There are, at the time of writing, 252 images on her Flickr stream – all of them are 444 pixel squares (although I gather she retains larger versions offline). Of the images the vast majority feature a face or figure and this is usually Tiringer herself, a strikingly good-looking but usually (only three or four of the self portraits have smiles) melancholy presence. The focus of the images is variable and the colours are largely muted and pastel. A number of the images feature text, mostly in Hungarian (and occasionally other eastern and central European languages and once or twice even English) and most of them are clearly the product of some process of collaging. What is striking about these images is how sophisticated the use of the space is – there is no sense whatsoever of any “algorithmic” approach to the making of these works – no recipe – each one feels thought through from the beginning and one can linger on each and find new and interesting content (by which I also mean marks, variations of focus or colour, absences, difficult to decipher sections) and relationships within it.

Some are funny (or perhaps lugubrious is a better word) with the kind of tinder dry poker faced humour I particularly associate with Eastern Europe (Nikolai Gogol… Jaroslav Hašek… István Örkény) and which seems to have further fermented as a regional characteristic during the period 1945 to 89. A number of the images either appear to be entirely drawn from albums of snapshots (maybe family, I’m not sure) or to feature components drawn from this kind of source.

A number of the images have drawings or written text added either by superimposition or in a separate space. Sometimes this takes the form of ink stamps or documents such as receipts or other official formats. Many images are divided into sections; sometimes of the same, repeated proportions, at others into something less structured. The sense of internal barriers marking off distinct sections is a strong one. These barriers are created in a number of ways – repetition, addition and the use of drawn or printed line.

The meaning of the texts, as much as I can make out the non-English ones, seems at least on the surface completely unrelated to the image content but, of course, the viewer naturally seeks such connections.

Many pieces employ “traditional” symbols of femininity – flowers, dolls, a killer dress sense. This also seems tied up with a summoning of the experience of growing up – we see a number of images of young girls. Again I’m unsure whether these are of a young Tiringer or simply found images. What does seem clear is that they carry some autobiographical charge. They are never twee (or if they do tread close, the surrounding work pulls them back from the brink and they become “about” tweeness – and if I can put it that way, the “whyness of tweeness” rather than exemplars of it). Equally the femininity cited above is certainly not inconsistent with strength and confidence. A number of the images allow us an intimacy which many self-portraitists would baulk at. Older women appear with relative frequency and are treated with tenderness and respect, as are images of daily household routines, of “women’s work”. Men appear in only two of the 252 images.

This image series is complex, subtle, sophisticated, mysterious and very beautiful. It is structured with a high level of intentionality by someone who is technically clearly completely in control of the visual language they are using but also open sudden dispatches from the unconscious. Whilst I’m always chary of ascribing “meaning” to works one can clearly delineate here a central set of concerns/hauntings/ pleasures/what-have-you which crop up repeatedly. Femininity, ageing and transition, female solidarity, day-dreaming and play, humour, storytelling, dressing-up (both the childish and the older sort) forming a kind of core around which other rarer, more peripheral themes appear and disperse.

This is not minor work.

3.

I interviewed Andrea Tiringer in English by e-mail over a couple of weeks in late August and early September 2014. Her responses appear largely in the order she sent them although I have interpolated some purely factual responses from an earlier exchange for clarity and I also corrected any (very few) errors of English usage. She checked the final interview text to ensure I had not altered the sense of any of her comments.

Could you tell us a bit about how you came to start making this very distinctive body of work and what you feel you are trying to accomplish with it?

I prefer to exist unrecorded. I take comfort in the temporary nature of things. I am always impatiently anticipating the new…. everything, I never want to hold the moment, yet somehow this photographic urge crawled into my life, without me taking notice.

The first step must have been years ago when I suddenly wanted to capture my grandma’s life. We had weekly sessions: her, me and my tape recorder. She was indecipherable. I tried to capture her essence. I needed her stories to be mine forever, figure out how to have a little ‘Róza mama’ transplanted into me. She expected me to be impossibly glamorous, the way she never could be. As far as she was concerned, that was my task. I was born at a time when girls could be scientists, astronauts, writers, but she did not want me to be a scientist, astronaut or writer, or only maybe as a side project to the grand life. She would look at my shoes and ask: were they expensive? The only acceptable response was: very.

Fast forward to about 2010 when for some reason I found myself chasing a nun on the street because I wanted to take her picture with my cell-phone. I have no idea why. I had no camera to my name, I had never before taken a photo on a whim. I caught up with her (she stopped to look at a shop window, my favourite kind of nun behaviour!) and at home I turned the poor thing, with the help of some online editing tool, into an unsightly shade of purple. I was pleased.

Some weeks later I threw a camera I found at home into my handbag, thinking, ‘Maybe I will run into something that I can take a picture of’. I saw a shabby garden through a ramshackle door. It was obvious right from the start that reality does not circumscribe me in any way.

I love kitsch. I adore bad taste. I fall for the maladroit.

So how did the very singular topics and imagery in the photos you post to Flickr came about? I’m particularly thinking of the repeated self portraiture which must be a feature of 90% of the pieces…

When I was a little girl I was convinced that just as we watch the people on TV someone somewhere is watching us, so we always have to show our best side. In my mind it worked like this: the interesting and good looking are on the telly, the rest on the radio. I would dress up to the nines and sing, because I figured if you did not have a good voice you only got to give the weather report,.

These auto-portraits are quickies. Passport photos, accessorized. Captures of what I am not but maybe could be. They are like a colourful puzzle. I never plan anything. (Actually I have planned to stop for about the last 100 images yet still I keep taking another one. I like them for a couple of days, even weeks sometimes, then forget about them, or they start to annoy me. I am a happy deleter.)

About a year ago I made an air freshener out of one. I adored that! I decided that if they are ever to materialize they will be just that: fake cherry scented tiny fake me’s dangling away in a cube shaped space and challenging visitors’ olfactory and visual endurance.

You say: “Captures of what I am not but maybe could be. They are like a colourful puzzle.”

Could you expand on both of these points? Could you say something about how the other content in any particular self portrait relates to the portrait itself and also what is happening in the pieces that don’t include a self portrait?

It’s extremely hard to describe a scheme as to how they are conceived. When I first started to create these images I haven’t taken a self-image for years. I did not even consider it, I captured what I liked, added my touch, altered them to the best of my abilities. I was getting familiar with the editing software through the process on my own, meaning there were many, many mishaps. Those were always welcome.

At some point the first auto-portrait must have happened, and of course I had all those traditional expectations: look good, appear interesting etc.

I started to think about scenes, but my goal was to create something that cannot be named, that is not easy to place, to find a category for. I avoided obvious symbols. No hearts, no crosses, no stars, nothing that could serve as a clue to the… who knows what?

When I choose the constituent elements, my decision is based only on the colour and geometry of each. This includes my attire and surroundings. For example, I look at the front of my blouse and it reminds me of ovaries; this leads me to a vintage anatomical model I printed the image of weeks ago, the colour of which somehow reminds me of a tiny burn I had on my skin at that time, so I took pictures of these and assembled an image from them..

Each has such individual stories, I never premeditate, it is such a quick process. As for the words, it amazes me the way sentences, taken out of their original context, suddenly stand bare: the absentminded cruelty in the prim cookbooks for proper ladies, the description of a slip-up from a madcap novel for teens that suddenly reads like major romantic poetry. I always photograph texts that catch my attention and if I find a loose connection I may add them to an image. Again, each one’s story is so unique, it’s hard to describe any rule or pattern.

I think there is no difference between the photos with me and the ones without me. I just haven’t found my place in each of them yet …

You’ve described quite lyrically and also humorously some of the personal sources and feelings behind the work. What I’d like you to do now is to talk us more clinically through the way, technically, that you set about making each image. Do you have, after so many, any set approach? What software do you use? How long does it take to make an image and do you make sketches or drafts before settling on the final version? Is there anything else about your approach you think is distinctive?

I use a point and shoot Nikon Coolpix, a simple, simple people-camera, I am not even sure of the exact make. I use GIMP to edit/composite.I have never made a sketch, I do not plan and plot. Something happens and I register that and this results in an image. I am presented with a pear and I casually place it beside me and notice it could belong to the pattern of the dress I am wearing. I look at items from a past exhibition at the medical museum in Budapest and as I catch sight of my reflection on the screen I perceive a concordance between me and the disfigured fetus in formaldehyde. If in those situations I can reach my camera I take a quick photo and it may become part of one of my squares. I try to avoid any set method, the only rule being the square shape.

I love taking photos of strangers. I love happening upon strangers that I want to take photos of. I love happening upon anything at all that I want to take photos of but I noticed that I got pickier over the years.

The found images come from everywhere and anywhere. Family photos, my huge box of vintage snapshots, movie stills, random Google Earth takes. My only rule regarding these is that I have to take a photo of them. No scans, no screen caps… This enables me to add my own mishaps, to “destroy” the originals with my technical shortcomings.

Of course there are schemes I could use. If you tell me to create a photo I will tell you to come back in half an hour and I’ll have it. To you it will look like the rest of them. But if I wait for my moment it can be in ten minutes or never (and I do not care, this way it is extremely personal, diary-like).

The reason I feel like stopping after each one is because their increasing number makes it a challenge to make new things, not to find myself in a rut.

So finally, given the fact that you post your work to Flickr I want to know how you view yourself? An artist? Someone with art as a hobby? An outsider artist? Some completely other category? And I want to ask too, if you had the chance to show this work in an art world context – galleries &c – would this interest you? Who is the work for? Do have any thoughts on Flickr as a place to show your work?

Leaving you to chew all that over that I’d like to say a big thank-you for your time & for the care with which you have considered and answered these questions!

I absolutely adore this time, the now. Flickr and other interactive/social media sites, in my view, are like any non-virtual public space. Similarly to our sartorial choices and general behaviour, it is a place for quick exchange of personal information, the possibility of sending perceptible signals about who we are, how we see everything and how we ourselves are related to that everything, so this is a very natural extension of my presence.

I do not really seek a label to describe my relation to the pictures. Definitions provide reassurance and security, but they also mean restriction and responsibility and it is such a relief to have tiny spaces in my life without those.

Who are they for? Hard to tell. At one point I was thinking ‘How wonderful, my son will look at them and think, great, my mum so enjoyed being.’ At the moment this looks quite unlikely, I am too alive. I get the quick attentive glance, the like on Facebook and I am happy and then he heads right back to his world of scalpels and detached limbs in formaldehyde. It is kind of reassuring that nothing about them worries a young doctor.

I will happily display them in any context where they match (or clash) perfectly, and of course that includes the art world and any other world too…

Someone said to me ‘To you football is a matter of life or death!’

and I said ‘Listen, it’s more important than that’.

Bill Shankly

Drawing is one of the two oldest purely cultural – in the sense of playful, not directly concerned with keeping body and soul together like cooking or hunting or shelter – activities that comes down to us today directly in the form of artefacts from between 25 – 35 thousand years ago [1] (the other is music [2]). There is no known human culture that has not made representational and other marks with something, on something, for both fun and survival. Furthermore, as Patrick Maynard demonstrates in his steely eyed and magisterial Drawing Distinctions [3], it can be shown to be the practice which more than any other underpins not only all of present day visual culture (including photography, which, following Maynard [4], we read as a species of drawing) but also the technical developments of our advanced industrial age. With satisfying circularity, drawing, a fundamental tool for engineers and architects, scaffolds the level of production which (by guaranteeing surplus product) is the prerequisite for the very existence of our substantial caste of artists and designers, those useless and indispensable dreamers.

Arguably, then, in a perfect world its study might be counted, with literacy and numeracy, as a genuinely key skill to be studied by all. Certainly, perhaps a more realistic demand, it should be a practice both underpinning and overarching any systematic education in art and design. What concrete shape might this take within the Babel of practices which current art education encompasses?

A couple of years ago the two of us, both from a background in digital art/moving image, started teaching on two consecutive courses – a Foundation degree in Digital Art and Design and its top-up, a BA (Hons) degree in Art and Design Practice. Much of the formal documentation of the courses specified the use of particular kinds of software and allegedly real-world reasons for deploying them (many involving the demands of “industry”). From the start we were antagonistic to this approach. We wanted to “artify” the course – introduce as much experimental, speculative, exploratory, pleasurable and downright pointless (in the way that the best art is both pointless and hugely important) activity as possible. We didn’t abandon the idea of teaching design, but we did decide that the core course programme would henceforth be art/design agnostic – it would deal with ways of making and thinking about images (as well as sound, performance, interactions or concepts) that could be used with profit by students moving in either or both or other directions. It would not be training; work would be driven by the imagination and shaped by the ambitions of students. Teachers would introduce new technical processes, but these would be embedded in thematically organised investigations of historic and contemporary precedents. Help with technique or software might be part of what teachers did, but this would be part of an organic investigation/development by student and teacher together. If a teacher knew something they would help; if they didn’t, they might know where to look; if neither knew, they might search together; if the student knew, they could teach other students and the teacher too. In short we identified a peer-learning process as the only sensible approach sufficient for developing the necessary skills, knowledge and flair in a rapidly-developing field.

Moreover we wanted a course that integrated the digital with every other sort of visual (and conceptual, performative and sonic) practice. We were both impatient with the idea that work made using digital tools, or work created within and distributed across a network, was somehow qualitatively different from all that had preceded it (a not uncommon view often allied to a species of digital mysticism). Indeed we realised we both sensed, and gradually came to articulate clearly, that there was a continuum – a chain – from the cave painter to the contemporary artist. Not to say that social and historical concreteness plays no explicatory role, but that there is some still human centre to mark making (and to allied practices – singing, the telling of tales, etc.) which has persisted and will persist and is part of the territory of being human. ’A chain’ is no loose metaphor, but a precise account of the reality. Inspiration and technique pass continuously from generation to generation. And this is cumulative – making much of the past of art available to its future. In a sense the terrain of art accretes, expands, as time passes. Even what is lost to famine or war, proscription, taste and changes in technology leaves traces, the possibility of reconstruction and re-use (and, often most creatively, misuse). This is what we wanted to instil in our students.

Our drawing sessions link to and are inspired by earlier instances of art powered pedagogy that place cross-form conversation at the heart of learning together. Joseph Beuys made drawings throughout his artistic life – often enigmatic constellations of media, concepts, entities, political figurations and material properties. However of particular relevance here are his extended works, Office of the Organization for Direct Democracy by Popular Vote for 100 days at documenta 5, 1972 and Honey Pump in the Workplace for documenta 6 in 1977, in which he demonstrates his expanded notion of art that is exactly congruous with his philosophy of teaching – ‘to reactivate the “life values” through a creative interchange on the basis of equality between teachers and learners.’ [5] Both pieces required the involvement of many people in processes outside of the realms of ordinary action (such as the maintenance of the plastic pipes of the honey pump as it circulated 2 tonnes of honey through the building) in order that they might connect with unfamiliar concepts and experiences. The artworks integrated many different categories of work (some, but not all, associated with art making) including performance and the practice of various disciplines (of dialogue, rhetoric, democratic processes of exchange and decision making). And yet, in an interview with Achille Bonito Oliva, Beuys makes it clear that he has no interest leading audiences towards an “activism devoid of content” [6]. The liberation of humankind through art (Beuys proposes that everyone is an artist and society is to be sculpted by everyone) depends on a more deliberate engagement of individual energies.

Drawing was particularly important to both of us. It was something Ruth had always done from an early age. Collections of drawings made by her between the ages of six and thirteen depict public street scenes of everyday social groupings and activities (a group of kids running with a dog, two mothers with two prams, businessmen waiting for a bus). The figures are too small to carry facial expressions. Nevertheless their interactions, mood, social status and relationships are expressed by their outfits, gaits, their gestures and their proximity to each other and other elements of the scene. Ruth now looks back on these as evidence of an early growing fascination with sociality. Through school she learned that ‘drawing well’ meant producing an image as much like a photograph as one might render. Praise and grades were awarded accordingly. Later, at art school, drawing became a liberating process of discovery. She generated abstract marks, as traces of energies within the body, rather than to create a deliberate composition within a pictorial plane. In this way she produced surfaces such as might be produced by soot covered animals (think monkey, gazelle, seal, tiger, crow) thrown together into a white room. This surface would then serve as a mirror (or crystal ball) from which entities, gestures and forms of light and shadow emerged to be drawn out in further explorations of aspects of her unconscious.

Drawing was something that Michael aspired to. Because he had come to moving image work – to “being an artist” – by a strange route through theatre, maths and music, he had both a fascination with and a terror of drawing. He had been the kid in the class who couldn’t draw, and yet had loved the feeling, the deep engagement with both the act and with what it awoke inside him –his mind’s eye – that it brought. In his moving image work he had attempted to confront this. The inverted commas that came with a certain species of conceptualism were a great help because he could frame himself performatively, comically almost, as an uncertain but oh-so-willing draftsperson, one with no eye or dexterity, a technical schlemiel.

In his secret heart, though, he knew he wanted to do this thing without (or at least largely without) irony.

Arising out of this obsession, in the early years of the new millennium, Michael had launched a little provocation where he challenged digital artists, as they were then still called, to create self-portraits, on the sole condition that this be done using non-digital means, and subsequently to photograph them for display in an online archive. Those who didn’t baulk at the task produced a touching and intriguing panorama, of pen and paint and pencil but also of bathroom tile, egg tempera and iron filings… [7]

As part of a discussion about this Michael had opined on some listserv or other that the barriers between artistic practices were porous and that the true measure of anyone aspiring to be an artist (musician, film maker, poet) was that, if lost in a deep forest or desert isle, with only a rock to make some marks on and another rock to make those marks with, the putative artist would eventually produce something of interest, depth and value.

Early on we introduced chunks of drawing as an occasional workshop – Ruth introduces, and then builds on familiar art school, Bauhaus type exercises that attempt to separate process from outcome-anxiety, allowing students to engage with an inner dialogue about their looking and representation un-disrupted by fears of inadequacy. These include:

drawing without looking at the paper; from memory; without removing pencil from paper; drawing with the “wrong” hand; drawing in five minutes or five seconds; drawing only negative space; having the pencil trace the movement of the eyeball as the drawer observes an object, etc.

Michael felt the centrality of drawing calling him but these sessions still felt like a slightly naughty holiday, an activity that did not necessarily link to his background and formation as an artist. The teacher, like the student, was still exploring.

The big epiphany came with the introduction of a weekly drawing session for all three years of the course. It happened and happens every Monday of term, without fail, and everyone in the room takes part, staff included. As many days as possible where more than one member of staff is present in the room, to make for debate, thus modelling civilised disagreement and forcing students, ultimately, to make up their own minds; there are usually two members of staff and occasionally more present. Each drawing session is led by a student who brings in an object, procedure or puzzle for the rest of us to address.

What happened is that we were rapidly out-Bauhaused by our students. Byzantine sets of instructions for tasks that we as teachers would have rejected out of hand as overly complex, impractical or confusing were carefully explained by students and then carried out by all of us in utter silence.

Half an hour elapses, we place our sets of images on the floor and we process around them all, discussing them. The important thing is that everyone has drawn. Everyone is both vulnerable and admirable. Teachers are not privileged. For students, it is understood that although the process carries course credit, what is being marked eventually is a series of drawings – some “good”, some “bad”, most neither – and that technique – whatever that is – is not the focus. There must be room for play in creative education; hence, for this part of the course, taking part in all of the sessions is enough to secure a pass.

With respect to collective feedback, our experience has been that perceptive kindness predominates. We search for the wonderful things, speculating on why they are wonderful, maybe asking questions of the person who has made this thing, trying to elicit that week’s secret or lesson. The drawings are a pleasure to behold. We have no intention of reproducing any of them here, though many would bear reproduction – we do not want to betray the egalitarian, labouring-together ethos of the thing by selecting outside the sessions and group. We are not sentimentalists – it is precisely because we understand the necessary element of brutality involved in the fair administration of an assessed course that we want to create oases, visions of how things could be other. It is the collective production of shared work that matters – it is not, let us emphasise though, a privileging of “process over production”. The production matters – desperately so. [8]

Over the weeks, our drawings are diverse in category, style, media and technique including: illustrations of the set task, abstractions, naïve figurations, diagrams, signs; some are performances of processes made in pencil, pen, paper, wood, charcoal, paint, collage, arrangements of plastic objects, paper-constructions; they reveal our choices and learning. Some students advance arguments in their drawings either with each other or with their own earlier work. As new tasks are set we each decide in the moment whether we understand the activity we are to involve ourselves with is mundane, ritualistic (perhaps even sacred), mad or wise, pointless or significant – our conclusions shape our drawings. In this way collective drawing has become central to the ethos of our courses as an integrative practice for negotiating a shared studio culture and shaping our learning together, our movement towards collegiality. Doing the drawing means the week has a start to it – we affirm ourselves as folk with a common interest, different but equal. The sessions have helped to provide a social glue, too, across the three years of the course.

There are areas where we as teachers know more than the students; both of us have track records of work in the art world, but the drawing sessions level us all – they enable a mutually supportive but acute look at progress on a common task. Since the drawing started we have also incorporated its lessons to other disciplines; staff and students share their photography work in a more horizontal way than the demands of the course would normally allow. We use new forms of social media, and have Flickr accounts in which all participants are contacts.[9] We comment on and “favourite” each other’s works as equals and collaborators.

Both drawing and photography in these contexts devolve to something similar – filling a blank space by mark making, with valuable, experiential knowledge accrued: repeating processes many times over to find out what constitutes skill and when (often, it turns out, much more often than is often acknowledged) to accept the gifts brought by chance; discovering that the art happens in a social space between the maker, the wider world and the viewer; understanding the work of others because we do it side by side; and, finally, coming to grips with the question of personal style and the diversity of ways of doing things well and meaningfully.

Each week reveals both artistic phylogeny and ontogeny – we solve the problem here and now, as if for the first time ever and this illuminates the historical chain, the intertwining of theory and practice, our mutual dependence, all of us artists and all of us nourished by art too.

—-

Originally written for Drawing Knowledge (2012). Tracey, The Journal of Drawing and Visualisation Research, Loughborough University.

Revised and republished Miller, A & Strong, J. (eds). (2012) Research-Led and Research-Informed Teaching. CREST Publishing.