The 21st conference of the Disruption Network Lab “Borders of Fear” was held on the 27th, 28th, and 29th November 2020 in Berlin’s Kunstquartier Bethanien. Journalists, activists, advocates, and researchers shed light on abuses and human rights violations in the context of migration management policies. Keynote speeches, panel discussions and several workshops were held involving a total number of 18 speakers and bringing together hundreds of online viewers.

Drawing on insights from humanities, science and technology studies, participants analysed from different perspectives the spread of new forms of persecution and border control targeting people on the move and those seeking refuge. They reflected collectively on forms of social justice and discussed the politics of fear that crystalize the stigmatisation of migrants. By concretely addressing these issues the conference also investigated the deployment of technology and the role of media to consolidate a well-defined structure of power, and outlined the reasons behind the rise of borders and walls, factors that lead to cultural and physical violence, persecution, and human rights violations.

In her introductory statement Dr. Tatiana Bazzichelli, founder and director of the Distruption Network Lab, presented the programme of the conference meant to address the discourse of borders both in their material function, and in their defining role within a strategy of dehumanization and racialisations of individuals. Across the globe, an unprecedented number of people are on the move due to war, economic and environmental factors. Bazzichelli recalled the urgent need to discuss human-right-related topics such as segregation and pushbacks, refugee camps and militarization of frontiers, considering the new technological artilleries available for states, investigating at the same time how border policing and datafication of society are affecting the narrative around migrants and refugees in Europe and the in the West.

The four immediate key content takeaways of the first day were the will to prevent people from reaching countries where they can apply for refugee status or visa; the externalisation polices of border control; the illegal practice of pushbacks; and systematic human rights violations by authorities, extensively documented but difficult to prove in court.

The conference opened with the short film by Josh Begley “Best of Luck with the Wall” – a voyage across the US-Mexico border – stitched together from 200,000 satellite images, and a talk by lawyer Renata Avila, who gave an overview of the physical and socio-economic barriers, which people migrating encounter whilst crossing South and Central America.

Avila took step from the current crises in South and Central America, to describe the dramatic migration through perilous regions, a result of an accumulation of factors like inequality, corruption, mafia, and violence. Avila pointed out that oligarchic systems from different countries appear to be interconnected in complicated architectures of international tax evasion, ruthless exploitation of resources, oppression, and the use of force. In those same places, people experience the most brutal inequality, poverty and social exclusion.

Since the ‘90s the regional free trade agreement meant open borders for products but not for people. In fact, it was an international policy with devastating effects on local economies and agriculture. People on the move in search for a better future somewhere else found closed borders and security forces attempting to block them from heading north towards Mexico and the U.S. border. In these years, the police forceful response to the migrants crossing borders have been widely praised by the governments in the region.

The fact of travelling alone is a red flag, especially for women, and the first wall people meet is in their own country. People on their way to the north experience every kind of injustice. Latin America has often been regarded as a region with deep ethnic and class conflicts. Abandoning possible stereotypical representations, we see that the bodies of the people on the move are at large sexualised and racialized for political reasons. Race, therefore, is another factor to consider, especially when we look at the journey of individuals on the move. Aside, languages in South America could also represent a barrier for those who travel without translators in a continent with dozens of indigenous languages.

Avila concluded her intervention mentioning the issue of digital colonialism and the relevance of geospatial data. Digital is no longer a separated space, she warned, but a hybrid one relevant for all individuals and whose rules are dictated by a small minority. People and places can be erased by those very few companies that can collect data, and –for example– draw and delete borders.

The panel on the first day titled “Migration, Failing Policies & Human Rights Violations,” was moderated by Roberto Perez-Rocha, director for the international anti-corruption conference series at Transparency International, and delivered by Philipp Schönberger and Franziska Schmidt, coordinators of the Refugee Law Clinic Berlin, together with investigative journalist and photographer Sally Hayden. The panellists referred to their direct experience and work, and reflected on how the EU migration policy is factually enforcing practices that cause violation of human rights, suffering, and desperation.

The Refugee Law Clinic Berlin e. V. is a student association at the Humboldt University of Berlin, providing free of charge and independent legal help for refugees and people on the move in Berlin and on the Greek island of Samos. The organisation also offers training on asylum and residence law in Berlin and runs the website ihaverights.eu, designed to allow access to justice to those in marginalised communities.

Through a legal counselling project on the Greek island of Samos, the collective helps people suffering from European illegal practices at the Union’s borders, providing the urgent need of effective ways to guarantee them access to justice and protection. As Schönberger and Schmidt recalled, refugees, and people on the move within the EU find several obstacles when it comes to the enforcement of their rights. For such a reason, they shall be guaranteed procedural counselling by the law to secure, among other services, a fair asylum procedure. However, the Clinic confirmed that such guarantees are not being completely fulfilled in Germany, nor at Europe’s borders, in Samos, Lesvos, Leros, Kos, or Kios.

The panellists explained how their presence on the island gives a chance to document that these camps of human suffering are actually a structural part of an EU migration policy aimed at deterring people from entering the Union, result of deliberate political decisions taken in Brussels and Berlin. Human rights violations occur before arriving on the island, as people are intercepted by the Greek coastguard or by the European Border and Coast Guard Agency (Frontex), and then pushed back to the Turkish border.

The camp in Samos, with a capacity of a maximum 648 people, is instead the home to 4,300 residents, with no water, no sanitary services, poisonous food, and no medical services. Even very serious cases documented to local health authorities remain unattended. The list of violations is endless and the complete lack of adequate protection for unaccompanied minors represents another big issue in this like in all others Greek hotspots, together with the precarity of vulnerable groups, whose risks increase with race, gender, and sexual identity.

The legal team from Berlin prepares applications to the EUCHR court and in these years has filed also 60 requests for urgent procedure due to the risk of irreparable harm, which were granted, ordering adequate accommodation and medical treatment for people in extreme danger.

Many observers criticise that the sufferings in the Aegean and on the Greek islands is the result of precise political decisions. Agreed in March 2016, the EU-Turkey deal is a statement of cooperation that seeks to control the crossing of people from Turkey to the Greek islands. According to the deal, every person arriving without documents by boat or without official permission or passage to the Greek islands would be returned to Turkey. In exchange, EU Member States would take Syrian refugees from Turkey. NGOs and international human rights agencies denounce that Turkey, Greece, and the EU have completely failed on humanitarian grounds and dispute the wrong premise that Turkey is a safe country for refugees and asylum-seekers.

Journalist and photographer Sally Hayden looked at the EU-Turkey deal, defining it as a prototype for what would then happen in the central Mediterranean. Libya, a country at war with multiple governments, is the destination of people on move and refugees from all over Africa, willing to cross the Mediterranean Sea. As it is illegal to stop and push people back, for years now the EU has been financing the Libyan coastguard to intercept and pull them back. What follows is a period of arbitrary and endless detention.

Hayden writes about facts; she is not an activist. When she talks about Libya, she refers to objective events she can fact check, and individual stories she has personally collected. Her reports represent a country at war, unsafe not just for refugees and people on the move but for Libyans too. With her work, the journalist has extensively documented how refugees and migrants smuggled into Libya are subject to human trafficking, forced labour, sexual exploitation and tortures, trapped in an infernal circle of violence and death. She recalled her experience with the detainees in Abu Salim, where 500 hundred people suffer from illegal and brutal incarceration inside a centre affiliated with the government in Tripoli. In July 2020, during the conflict, one of these many prisons not far from the city was bombed. At least 53 illegally detained people were killed.

Hayden’s work provides a picture of the results of Europe’s management of the migration crises in the Mediterranean and Northern Africa. EU funds are employed for militarization of borders and externalisation of frontiers control. The political context, in which this occurs, is the cause of years and sometimes decades of lack of investment in reception and asylum systems in line with EU-State’s generic obligations to respect, protect and fulfil human rights.

All panellists called for the immediate intervention to evacuate camps and prisons that were the result of the EU migration policies, to allow migrant victims of abuses and refugees to seek justice and safety elsewhere.

The evening closed with the panel discussion titled “Illegal Pushbacks and Border Violence” and moderated by Likhita Banerji, a human rights and technology researcher at Amnesty International. Banerji reminded the audience that in the first nine months of 2020 there had already been 40 pushbacks, illegal rejections of entry, and expulsions without individual assessment of protection needs, had been documented within Europe or at its external borders. Since these illegitimate practices are widespread, and in some countries systematic, these pushbacks cannot be defined as incidental actions. They appear, instead, to be institutionalised violations, well defined within national policies.

People who shall receive asylum or be rescued, are instead pushed back by police forces, who make sure that the material crossing of the borders remains undocumented. EU member States want to keep undocumented migrants, asylum seekers and refugees outside of their jurisdiction to avoid moral responsibilities and legal obligations. During the second panel of the day, Hanaa Hakiki, legal advisor at the ECCHR Migration Program, filmmaker and reporter Nicole Vögele, and Dimitra Andritsou, researcher at Forensic Architecture, had the chance to go in-depth and to consider the different aspects of these violations.

Hanaa Hakiki, in her intervention “Bringing pushbacks to justice” presented the difficulties that litigators experience in court to materially document pushbacks, which are indeed not meant to be proven. She defined pushbacks as a set of state measures, by which refugees and migrants are forced back over the border – generally shortly after having crossed it – without consideration of their individual circumstances and without any possibility for them to apply for asylum or to put forward arguments against the measures taken.

There are national and international laws that need to be considered in these cases, constituting binding legal obligations for all EU Member States. As a general principle, governments cannot enact disproportionate force, humiliating and degrading treatment or torture, and must facilitate the access to asylum, guarantee protection to people, and provide them access to individualised procedures in this sense.

Member States know that pushbacks have been illegal since a 2012 ECtHR judgment, known as the “Hirsi Jamaa Case,” which found that Italy had violated the law in forcing people back to Libya. However, the effective ban on direct returns led European countries to find other ways to avoid responsibility for those at sea or crossing their borders without documents, and concluded agreements with neighbouring countries, which are requested to prevent migrants from leaving their territories and paid to do so, by any means and without any human rights safeguards in place. By outsourcing rescue to the Libyan authorities, for example, pushbacks by EU countries turned into pullbacks by Libyan coastguard.

Land-pushbacks are still common practice. Hakiki explained that the European Centre for Constitutional and Human Rights (ECCHR) has worked with communities of undocumented migrants since 2014, considering potential legal interventions against the practice of pushbacks at EU borders, and assisting affected persons with individual legal proceedings. She presented three cases the ECCHR litigated in Court (N.D. and N.T. v. Spain; AA vs North Macedonia; SB vs. Croatia) proving that European countries illegally push people back, in violation of human rights laws. Despite the fact that this is still a common practice, it is very difficult to document these violations and have the authorities condemned.

During the beginning of the Syrian conflict, in 2015, refugees were able to travel via Serbia and Hungary into Central and Northern Europe. A couple of years later the EU decided to close down again this so-called Balkan Route, with the result that more and more people found themselves stuck in Bosnia-Herzegovina, prevented from continuing onward to Europe’s territories. From there a person can try to enter the European Union dozens of times, and each time is stopped by Croatian security forces, beaten, and then dragged back across the border to Bosnia-Herzegovina.

After having seen the effects of these illegal practices and met victims of dozens of violent pushbacks in Sarajevo, in 2019 the reporter Nicole Vögele and her crew succeeded in filming a series of these cross-border expulsions from Croatia to Bosnia Herzegovina near the village of Gradina, in the municipality of Velika Kladuša. The reporter, one of the few who succeeded in documenting this practice, also interviewed those who had just been pushed back by the Interventna Policija officers. The response of the Bosnian authorities to her reportage was a complete denial of all accusations.

Vögele then presented footage taken at the EU external border in Croatia, in March 2020, showing masked men beat up refugees and illegally pushing them back to Bosnia. The journalist and her team found the original video, analysed its metadata, and interviewed the man captured on it. Once again, their work could prove that these practices are not isolated incidents.

The panel closed with the investigation by Forensic Architecture part of a broader project on cases of pushbacks across the Evros/Meriç river. Team member Dimitra Andritsou presented the organisation founded to investigate human rights violations using a range of techniques, flanking classical investigation methods including open-source investigation video analysis, spatial and architectural practice, and digital modelling.

Forensic Architecture works with and on behalf of communities affected by state and military violence, producing evidence for legal forums, human rights organisations, investigative reporters and media. A multidisciplinary research group – of architects, scholars, artists, software developers, investigative journalists, archaeologists, lawyers, and scientists – based at the University of London, works in partnership with international prosecutors, human rights organisations, political and environmental justice groups, and develops new evidentiary techniques to investigate violations of human rights around the world, armed conflicts, and environmental destruction.

The Evros/Meriç River is the only border between Greece and Turkey that is not sea. For years migrants and refugees trying to cross it to enter Europe have been reporting that unidentified and generally masked men catch, detain, beat, and push people back to Turkey. Mobile phones, documents, and the few personal things they travel with are confiscated or thrown into the river, not to leave any evidence of these violations behind. As Andridsou described, both Greek and EU authorities systematically deny any wrongdoing, refusing to investigate these reports. The river is part of a wider ecosystem of border defence and has been weaponised to deter and let die those who attempt to cross it.

In December 2019, the German magazine Der Spiegel obtained rare videos filmed on a Turkish Border Guard’s mobile phone and on a surveillance, camera installed on the Turkish banks of the river, which apparently documented one of these many pushback operations. Forensic Architecture was commissioned to analyse the footages. A team of experts was then able to geolocate and timestamp the material and could confirm that the images were actually taken few hundred metres away from a Greek military watchtower in Greece.

Andritsou then presented the case of a group of three Turkish political asylum seekers, who entered Greek territory on 4 May 2019, always crossing the Evros/Meriç river. In this case a team of Forensic Architecture could cross-reference different evidence sources, such as new media, remote sensing, material analysis, and witness testimony and verify the group’s entry and their illegal detention in Greece. A pushback to Turkey on the 5 May 2019 led to their arrest and imprisonment by the Turkish authorities.

Ayşe Erdoğan, Kamil Yildirim, and Talip Niksar had been persecuted by the Turkish government on allegations of involvement in Fettulah Gulen’s movement. The group on the run had shared a video appealing for international protection against a possible forced return to Turkey and digitally recorded the journey via WhatsApp. All their text messages with location pins, photographs, videos and metadata prove their presence on Greek soil, prior to their arrest by the Turkish authorities. The investigation could verify that the three were in a Greek police station too, a fact that matches their statement about having repeatedly attempted to apply for asylum there. Their imprisonment is a direct result of the Greek authorities contravening the principle of non-refoulement.

Some keywords resonated throughout the first day of the conference, as a fil rouge connecting the speakers and debates held during the panels and commentaries by the public. Violence, arbitrariness and lawlessness are wilfully ignored –if not backed– by EU Member States, with authorities constantly trying to hide the truth. Thousands of people live under segregation, with no account or trace of being in custody of authorities free to do with them whatever they want.

Technology has always been a part of border and immigration enforcement. However, over the last few years, as a response to increased migration into the European Union, governments and international organisations involved in migration management have been deploying new controversial tools, based on artificial intelligence and algorithms, conducting de facto technological experiments and research involving human subjects, refugees and people on the move. The second day of the conference opened with the video contribution by Petra Molnar, lawyer and researcher at the European Digital Rights, author of the recent report “Technological Testing Grounds” (2020) based on over 40 conversations with refugees and people on the move.

When considering AI, questions, answers, and predictions in its technological development reflect the political and socioeconomic point of view, consciously or unconsciously, of its creators. As discussed in the Disruption Network Lab conference “AI traps: automating discrimination” (2019)— risk analyses and predictive policing data are often corrupted by racist prejudice, leading to biased data collection which reinforces privileges of the groups that are politically more guaranteed. As a result, new technologies are merely replicating old divisions and conflicts. By instituting policies like facial recognition, for instance, we replicate deeply ingrained behaviours based on race and gender stereotypes, mediated by algorithms. Bias in AI is a systematic issue when it comes to tech, devices with obscure inner workings and the black box of deep learning algorithms.

There is a long list of harmful tech employed at the EU borders is long, ranging from Big Data predictions about population movements and self-phone tracking, to automated decision-making in immigration applications, AI lie detectors and risk-scoring at European borders, and now bio-surveillance and thermal cameras to contain the spread of the COVID-19. Molnar focused on the risks and the violations stemming from such experimentations on fragile individuals with no legal guarantees and protection. She criticised how no adequate governance mechanisms have been put in place, with no account for the very real impacts on people’s rights and lives. The researcher highlighted the need to recognise how uses of migration management technology perpetuate harms, exacerbate systemic discrimination, and render certain communities as technological testing grounds.

Once again, human bodies are commodified to extract data; thousands of individuals are part of tech-experiments without consideration of the complexity of human rights ramifications, and banalizing their material impact on human lives. This use of technology to manage and control migration is subject to almost no public scrutiny, since experimentations occur in spaces that are militarized and so impossible to access, with weak oversight, often driven by the private sector. Secrecy is often justified by emergency legislation, but the lack of a clear and transparent regulation of the technologies deployed in migration management appears to be deliberate, to allow for the creation of opaque zones of tech-experimentation.

Molnar underlined how such a high level of uncertainty concerning fundamental rights and constitutional guarantees would be unacceptable for EU citizens, who would have ways to oppose these liberticidal measures. However, migrants and refugees have notoriously no access to mechanisms of redress and oversight, particularly during the course of their migration journeys. It could seem secondary, but emergency legislation justifies the disapplication of laws protecting privacy and data too, like the GDPR.

The following part of the conference focused on the journey through Sub-Saharan and Northern Africa, on the difficulties and the risks that migrants face whilst trying to reach Europe. In the conversation “The Journey of Refugees from Africa to Europe,” Yoseph Zemichael Afeworki, Eritrean student based in Luxemburg, talked of his experience with Ambre Schulz, Project Manager at Passerell, and reporter Sally Hayden. Afeworki recalled his dramatic journey and explained what happens to those like him, who cross militarized borders and the desert. The student described that migrants represent a very lucrative business, not just because they pay to cross the desert and the sea, but also because they are used as cheap labour, when not directly captured for ransom.

Once on the Libyan coast, people willing to reach Europe find themselves trapped in a cycle of waiting, attempts to cross the Mediterranean, pullbacks and consequent detention. Libya is a country at war, with two governments. The lack of official records and the instability make it difficult to establish the number of people on the move and refugees detained without trial for an indefinite period. Libyan law punishes illegal migration to and from its territory with prison; this without any account for individual’s potential protection needs. Once imprisoned in a Libyan detention centre for undocumented migrants, even common diseases can lead fast to death. Detainees are employed as forced labour for rich families, tortured, and sexually exploited. Tapes recording inhuman violence are sent to the families of the victims, who are asked to pay a ransom.

As Hayden and Afeworki described, the conditions in the buildings where migrants are held are atrocious. In some, hundreds of people live in darkness, unable to move or eat properly for several months. It is impossible to estimate how many individuals do not survive and die there. An estimated 3,000 people are currently detained there. The only hope for them is their immediate evacuation and the guarantee of humanitarian corridors from Libya –whose authorities are responsible for illegal and arbitrary detention, torture and other crimes– to Europe.

The second day closed with the panel “Politics & Technologies of Fear” moderated by Walid El-Houri, researcher, journalist and filmmaker. Gaia Giuliani from the University of Coimbra, Claudia Aradau, professor of International Politics at King’s College in London, and Joana Varon founder at Coding Rights, Tech and Human Rights Fellow at Harvard Carr Center.

Gaia Giuliani is a scholar, an anti-racist, and a feminist, whose intersectional work articulates the deconstruction of public discourses on the iconographies of whiteness and race, questioning in particular the white narrative imaginary behind security and borders militarization. In her last editorial effort, “Monsters, Catastrophes and the Anthropocene: A Postcolonial Critique” (2020), Giuliani investigated Western visual culture and imaginaries, deconstructing the concept of “risk” and “otherness” within the hegemonic mediascape.

Giuliani began her analyses focusing on the Mediterranean as a border turned into a biopolitical dispositive that defines people’s mobility –and particularly people’s mobility towards Europe– as a risky activity, a definition that draws from the panoply of images of gendered monstrosity that are proper of the European racist imaginary, to reinforce the European and Western “we”. A form of othering, the “we” produces fears through mediatized chronicles of monstrosity and catastrophe.

Giuliani sees the distorted narrative of racialized and gendered bodies on the move to Europe as essential to reinforce the identification of nowadays migrations with the image of a catastrophic horde of monsters, which is coming to depredate the wealthy and peaceful North. It´s a mechanism of “othering” through the use of language and images, which dehumanizes migrants and refugees in a process of mystification and monstrification, to sustain the picture of Europe as an innocent community at siege. Countries of origins are described as the place of barbarians, still now in post-colonial times, and people on the move are portrayed as having the ability to enact chaos in Europe, as if Europe were an imaginary self-reflexive space of whiteness, as it was conceived in colonial time: the bastion of rightfulness and progress.

As Giuliani explained, in this imaginary threat, migrants and refugees are represented as an ultimate threat of monsters and apocalypse, meant to undermine the identity of a whole continent. Millions of lives from the South become an indistinct mass of people. Figures of race that have been sedimented across centuries, stemming from colonial cultural archives, motivate the need to preserve a position of superiority and defend political, social, economic, and cultural privileges of the white bodies, whilst inflicting ferocity on all others.

This mediatized narrative of monsters and apocalypse generates white anxiety, because that mass of racialized people is reclaiming the right to escape, to search for a better life and make autonomous choices to flee the objective causes of unhappiness, suffering, and despair; because that mass of individuals strives to become part of the “we”. All mainstream media consider illegitimate their right to escape and the free initiative people take to cross borders, not just material ones but also the semiotic border that segregate them in the dimension of “the barbarians.” An unacceptable unchained and autonomous initiative that erases the barrier between the colonial then and the postcolonial now, unveiling the coloniality of our present, which represents migration flows as a crisis, although the only crisis undergoing is that of Europe.

On the other side, this same narrative often reduces people on the move and refugees to vulnerable, fragile individuals living in misery, preparing the terrain for their further exploitation as labour force, and to reproduce once again racialized power relations. Here the process of “othering” revivals the colonial picture of the poor dead child, functional to engender an idea of pity, which has nothing to do with the individual dignity. Either you exist as a poor individual in the misery –which the white society mercifully rescues– or as a part of the mass of criminals and rapists. However, these distinct visual representations belong to the same distorted narration, as epitomized in the cartoons published by Charlie Hebdo after the sexual assaults against women in Cologne on New Year’s Eve 2015.

Borders have been rendered as testing ground right for high-risk experimental technologies, while refugees themselves have become testing subjects for these experiments. Governments and non-state actors are developing and deploying emerging digital technologies in ways that are uniquely experimental, dangerous and discriminatory in the border and immigration enforcement context. Taking step from the history of scientific experiments on racialized and gendered bodies, Claudia Aradau invited the audience to reconsider the metaphorical language of experiments that orients us to picture high-tech and high-risk technological developments. She includes instead also tech in terms of obsolete tools deployed to penalise individuals and recreate the asymmetries of the digital divide mirroring the injustice of the neoliberal system.

Aradau studies technologies and the power asymmetries in their deployment and development. She explained that borders have been used as very profitable laboratories for the surveillance industry and for techniques that would then be deployed widely in the Global North. From borders and prison systems –in which they initially appeared– these technologies are indeed becoming common in urban spaces modelled around the traps of the surveillance capitalism. The fact that they slowly enter our vocabularies and daily lives makes it difficult to define the impact they have. When we consider for example that inmates’ and migrants’ DNA is collected by a government, we soon realise that we are entering a more complex level of surveillance around our bodies, showing tangibly how privacy is a collective matter, as a DNA sequence can be used to track a multitude of individuals from the same genealogic group.

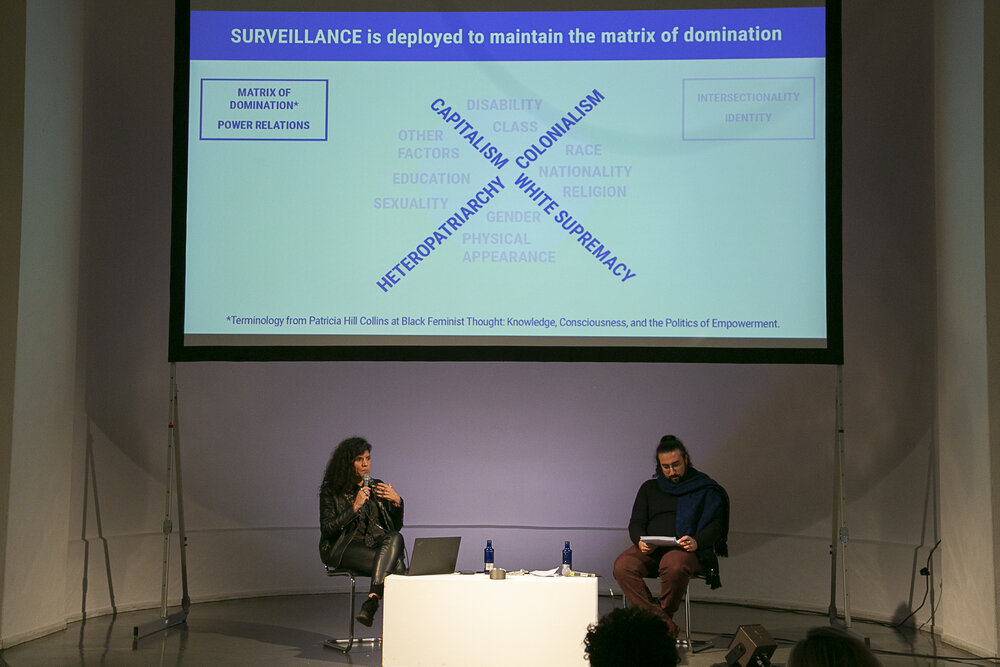

Whilst we see hyper-advanced tech on one side, on the other people on the move walk with nothing to cross a border, sometimes not even shoes, with their personal belongings inside plastic bags, and just a smartphone to orientate themselves, and communicate and ask for help. An asymmetry, which is –once again– being deployed to maintain what Aradau defined as matrix of domination: no surveillance on CO2 emissions and environmental issues due to industrial activities, no surveillance on exploitations of resources and human lives; no surveillance on the production of weapons, but massive deployment of hi-tech to target people on the move, crossing borders to reach and enter a fortress, which is not meant for them.

Aradau recalled that in theory, protocols ethics and demands for objectivity are necessary when it comes to scientific experiments. However, the introduction in official procedures of digital tech devices and software such as Skype, WhatsApp or MasterCard or a set of apps developed by either non-state or state actors, required neither laboratories nor the randomized custom trials that we usually associate with scientific experimentation. These heterogeneous techniques specifically intended to work everywhere and enforced without protocols, need to be understood under neoliberalism: they rely on pilot projects trials and cycles of funds and donors, whose goal is every time to move to a next step, to finance more experiments. Human-rights-centred tech is far away.

Thus, we see always more experiments carried out without protocols, from floating walls tech to stop migrants reaching the Greek shores, to debit cards used as surveillance devices. Creative experiments come also with the so-called refugees’ integration, conceived by small-scale injections of devices into their reality for limited periods, with the purpose of speculatively recompose rotten asymmetries of power and injustice. In Greece, as Aradau mentioned, the introduction of Skype in the process of the asylum application became an obstacle, with applicants continually experiencing debilitation through obsolete technology that doesn’t work or devices with limited access, disorientation through contradictory and outdated information.

There is also a factual aspect: old and slow computers, documents that have not been updated or have been updated at different times, and lack of personnel are justified by saying that resources are limited. A complete lack or shortage of funds, which is one other typical condition of neoliberalism, as we can see in Greece. In this, tech recomposes relations of precarity in a different guise.

Aradau concluded her contribution focusing on the technologies that are deployed by NGOs, completely or partially produced elsewhere, often by corporate actors who remain entangled in the experiments through their expertise and ownership. Digital platforms such as Facebook, Microsoft, Amazon, or Google not only shape relations between online users, she warned, but concerning people on the move and refugees too. Google and Facebook –for example– dominate the relations that underpin the production of refugee apps by humanitarian actors.

Google is at the centre of a sort of digital humanitarian ecosystem, not only because it can host searches or provide maps for the apps, but also because it simultaneously intercepts data flows so that it acts as a surplus data extractor. In addition, social networks reshape digital humanitarianism through data extractive relations and provide big part of the infrastructure for digital humanitarianism. Online humanitarianism becomes thus a particularly vulnerable site of data gathering and characterised by an overall lack of resources –similarly to the Greek state. As a result, humanitarian actors cannot tackle the depreciation messiness and obsolescence of their tech and apps.

The last day of the conference concentrated on the urgent need to creating safe passages for migration, and pictured the efforts of those who try to ensure safer migration options and rescue migrants in distress during their journey. Lieke Ploeger, community director of the Disruption Network Lab, presented the panel discussion “Creating Safe Passages”, moderated by Michael Ruf, writer and director of documentary and theatre plays. Ruf´s productions include the “Asylum Dialogues” (2011) and the “Mediterranean Migration Monologues” (2019), which have been performed in numerous countries more than 800 times by a network of several hundred actors and musicians. This final session brought together speakers from the Migrant Media Network (MMN), the Migrant Offshore Aid Station (MOAS), and SeaWatch e.V. to discuss their efforts to ensure safer migration options, as well as share reliable information and create awareness around migration issues.

The talk was opened by Thomas Kalunge, Project Director of the Migrant Media Network, one of r0g_agency’s projects, together with #defyhatenow. Since 2017 the organisation has been working on information campaigns addressed to people in rural areas of Africa, to explain that there are possible alternatives for safer and informed decisions, when they choose to reach other countries, and what they may come across if they decide to migrate.

The MMN team organises roundtable discussions and talks on various topics affecting the communities they meet. They build a space in which young people take time to understand what migration is nowadays and to listen to those, who already personally experienced the worst and often less discussed consequences of the journey. To approach possible migrants the MMN worked on an information campaign on the ethical use of social media, which also helps people to learn how to evaluate and consume information shared online and recognise reliable sources.

The MMN works for open culture and critical social transformation, and provides young Africans with reliable information and training on migration issues, included digital rights. The organisation also promotes youth entrepreneurship “at home” as a way to build economic and social resilience, encouraging youth to create their own opportunities and work within their communities of origin. They engage on conversations on the dangers of irregular migration, discussing together rumours and lies, so that individuals can make informed choices. One very relevant thing people tend to underestimate, is that sometimes misinformation is spread directly by human smugglers, warned Kalunge.

The MMN also provides people from remote regions with offline tools that are available without an internet connection, and training advisors and facilitators who are then connected in a network. The HyracBox for example is a mobile, portable, RaspberryPi powered offline mini-server for these facilitators to use in remote or offline environments, where access to both power and Internet is challenging. With it, multiple users can access key MMN info materials.

An important aspect to mention is that the MMN does not try to tell people not to migrate. European government have outsourced borders and migration management, supporting measures to limit people mobility in North and Sub-Saharan Africa, and it is important to let people know that there are real dangers, visible and invisible barriers they will meet on their way.

Visa application processes –even for legitimate reasons of travel– are very strict for some countries, often without any information being shared, even with people who are legitimately moving for education, to work or get medical treatment. The ruling class that makes up the administrative bureaucracy and outlines its structures, knows that who controls time has power. Who can steal time from others, who can oblige others to waste time on legal quibbles and protocol matters, can suffocate the others’ existence in a mountain of paperwork.

Human smugglers then become the final resort. Kaluge explained also that, at the moment, the increased outsourcing of the European border security services to the Sahel and other northern Africa countries is leading to diversion of routes, increased dangerousness of the road, people trafficking, and human rights violations.

Closing the conference, Regina Catrambone presented the work that MOAS does around the world and the campaign for safe and legal routes that is urging governments and international organisations to implement regular pathways of migration that already exist. Mattea Weihe presented instead the work of SeaWatch e. V., an organisation which is also advocating for civil sea rescue, legal escape routes and a safe passage, and which is at sea to rescue migrants in distress.

The two panellists described the situation in the Central Mediterranean. Since the beginning of the year, over 500 migrants have drowned in the Mediterranean Sea (November 2020). While European countries continue to delegate their migration policy to the Libyan Coast Guard, rescue vessels from several civilian organisations have been blocked for weeks, witnessing the continuous massacre taking place just a few miles from European shores. With no common European rescue intervention at sea, the presence of NGO vessels is essential to save humans and rescue hundreds of people who undertake this dangerous journey to flee from war and poverty.

However, several EU governments and conservative and far right political parties criminalise search and rescues activities, stating that helping migrants at sea equals encouraging illegal immigration. A distorted representation legitimised, fuelled and weaponised in politics and across European society that has led to a terrible humanitarian crisis on Europe’s shores. Thus, organisations dedicated to rescuing vessels used by people on the move in the Mediterranean Sea see all safe havens systematically shut off to them. Despite having hundreds of rescued individuals on board, rescue ships wait days and weeks to be assigned a harbour. Uncertainty and fear of being taken back to Libya torment many of the people on board even after having been rescued. After they enter the port, the vessels are confiscated and cannot get back out to sea.

By doing so, Europe and EU Member States violate human rights, maritime laws, and their national democratic constitutions. The panel opened again the crucial question of humanitarian corridors, human-rights-based policy, and relocations. In the last years the transfer of border controls to foreign countries, has become the main instrument through which the EU seeks to stop migratory flows to Europe. This externalisation deploys modern tech, money and training of police authorities in third countries moving the EU-border far beyond the Union’ shores. This despite the abuses, suffering and human-rights violations; willingly ignoring that the majority of the 35 countries that the EU prioritises for border externalisation efforts are authoritarian, known for human rights abuses and with poor human development indicators (Expanding Fortress, 2018).

It cannot be the task of private organizations and volunteers to make up for the delay of the state. But without them no one would do it.

States are seeking to leave people on the move, refugees, and undocumented migrants beyond the duties and responsibilities enshrined in law. Most of the violations, and the harmful technological experimentation described throughout the conference targeting migrants and refugees, occurs outside of their sovereign responsibility. Considering that much of technological development occurs in fact in the so-called “black boxes,” by acting so these state-actors exclude the public from fully understanding how the technology operates.

The fact that the people on the move on the Greek islands, on the Balkan Route, in Libya, and those rescued in the Mediterranean have been sorely tested by their journeys, living conditions, and, in many cases, imprisoned, seems to be irrelevant. The EU deploys politics that make people who have already suffered violence, abuse, and incredibly long journeys in search of a better life, wait a long time for a safe port, for a visa, for a medical treatment.

All participants who joined the conference expressed the urgent need for action: Europe cannot continue to turn its gaze away from a humanitarian emergency that never ends and that needs formalised rescue operations at sea, open corridors, and designated authorities enacting an approach based on defending human rights. Sea rescue organisations and civil society collectives work to save lives, raise awareness and demand a new human rights-based migration and refugee policy; they shall not be impeded but supported.

The conference “Borders of Fear” presented experts, investigative journalists, scholars, and activists, who met to discuss wrongdoings in the context of migration and share effective strategies and community-based approaches to increase awareness on the issues related to the human-rights violations by governments. Here bottom-up approaches and methods that include local communities in the development of solutions appear to be fundamental. Projects that capacitate migrants, collectives, and groups marginalized by asymmetries of power to share knowledge, develop and exploit tools to combat systematic inequalities, injustices, and exploitation are to be enhanced. It is imperative to defeat the distorted narrative, which criminalises people on the move, international solidarity and sea rescue operations.

Racism, bigotry and panic are reflected in media coverage of undocumented migrants and refugees all over the world, and play an important role in the success of contemporary far-right parties in a number of countries. Therefore, it is necessary to enhance effective and alternative counter-narratives based on facts. For example, the “Africa Migration Report” (2020) shows that 94 per cent of African migration takes a regular form and that just 6 per cent of Africans on the move opt for unsafe and dangerous journeys. These people, like those from other troubled regions, leave their homes in search of a safer, better life in a different country, flee from armed conflicts and poverty. It is their right to do so. Instead of criminalising migration, it is necessary to search for the real causes of this suffering, war and social injustice, and wipe out the systems of power behind them.

Videos of the conference are also available on YouTube via:

For details of speakers and topics, please visit the event page here: https://www.disruptionlab.org/borders-of-fear

Upcoming programme:

The 23rd conference of the Disruption Network Lab curated by Tatiana Bazzichelli is titled “Behind the Mask: Whistleblowing During the Pandemic.“ It will take place on March 18-20, 2021. More info: https://www.disruptionlab.org/behind-the-mask

To follow the Disruption Network Lab sign up for the newsletter and get informed about its conferences, meetups, ongoing researches and projects.

The Disruption Network Lab is also on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram.

Featured image: System Map by Andrea Crespo, 2015, image

Fear is easily attributable to a cause—we fear something in particular. Anxiety, however, can be described as fear without the source. Yet, anxiety is also a safety mechanism. Without it, we would walk in the face of danger. In the online exhibition Body Anxiety, curated by Leah Schrager and Jennifer Chan, the disquiet is experienced in the flesh, whether this is as a symptom or sublimation.

Whatever your gender, your body is politicised in ways you cannot control. If you are female, or gender queer, there is also a fight against power. The works in Body Anxiety specifically problematise the image of women in the media and in the art world. Women artists, they claim with good arguments, are powerless; sothe show gives time and space to a group of artists the curators call ‘female painters’. Even though few paint (in fact, probably only Schrager herself does), Schrager puts forward the argument of painting as the highest artistic form, one dominated my males. She recontextualises painting for this exhibition, where most artists use their own bodies as canvases for video performances, sound works, photographs and writing. Perhaps this is peinture féminine to Helene Cixous’ écriture féminine.

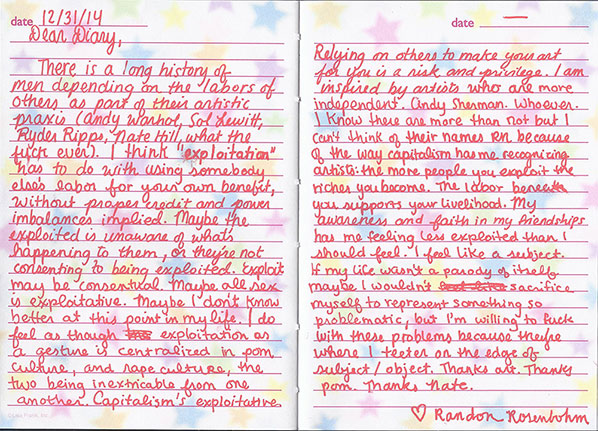

Good examples of the symptomatic are Victoria Campbell’s The Penelope Files, an auto-interview video with a reflexive sound monologue where she explores her thoughts on images of herself while browsing through her computer files. We hear her; we only see the screen. Exploring her relation to image, authorship, labour and the body, something about photography is revealed in the repetitive moving of files on her desktop’s finder window. Narrative also inhabits the work of Randon Rosenbohm. She presents a scan of a handwritten diary entry where artistic labour, exploitation and male artists feature. Her other work consists of a tumblr blog of rejected selfies. Both are pieces we should not see. This is also the case in Ann Hirsh’s video. Dance party just us girls shows footage that should be for private consumption, part of a home video, a laugh, documentation of a personal exploration. Using generic distorting video software available in most computers, the two-channel work shows the torso of a woman bobbing away to a song next to an image of moving genitalia, in a feminist version of Courbet’s painting The origin of the world. The two images share a pair of glasses and the genitalia is converted into a talking face, like in Denis Diderot’s libertine novel The Indiscreet Jewels.

Saoirse Walls’ Den Perfekte Saoirse(2012) quotes Jurgen Leth’s The Perfect Human. She replicates some of the famous body poses and music from the classic black and white film, showing us the best of her individual self in a sublimation. She can do a side crow, twerk, walk in heels and, thanks to camera tricks, have a 100% symmetrical face. The work gets more and more bizarre with the appearance of make up and hair extensions. Where has Leth’s serious exploration of perfection gone in her quote? What are we demanding of Saoirse Walls? Another good example of an impossible demand and how this conflict is shown in a work of art is Nancy Leticia’s video. Her youthful, gorgeous self plays piano in her underwear. She plays very well, but how does this relate to the image setting?

Screenshot of Den Perfekte Saoirse by Saoirse Wall, 2012, video, 2:22 mins

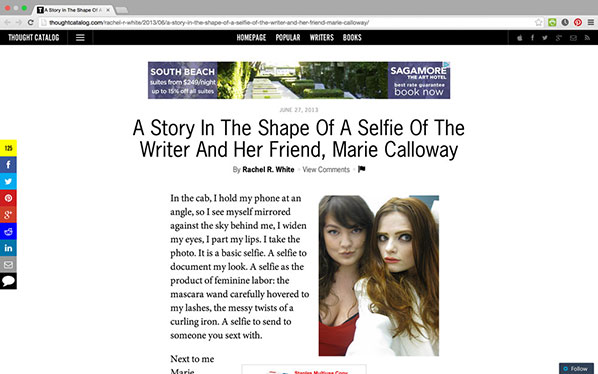

The writer Marie Calloway—an alt lit writer, also a female painter in the way Schrager intends—features in Rachel Rabbit White’s work A Story In The Shape Of A Selfie Of The Writer And Her Friend, Marie Calloway. Her writing with images addresses the issue of anxiety head on. ‘Refresh’, ‘refresh’, ‘refresh’, she writes at the end of a blog post-merging stories about Marie, public events, selfies, feminist writers and artists, and social media.

These diverse works are playful, at times irreverent, and certainly thought provoking. The curation is purposeful, direct and erudite. Yet, I have some issues with the display, with the sidebar prefaced by curatorial statements and with links to the artists’ biographies and websites. It feels more a catalogue than an exhibition. I don’t have a solution, though, as maybe this is a constraint of the medium. A few of the works are hosted on external websites—vimeo, red tube. Some of them even require passwords and this provokes a particular way of looking, a gaze, then a click, a search away from what is presented in front of us. I am an active viewer, often in the position of a Peeping Jane.

In her 1975 essay ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’ Laura Mulvey examines scopophilia, the pleasure in looking. This is not an innocent act. She argued that the relation between looker and looked is unequal in cinema, with woman as image and man as bearer of the look. If woman is a ‘one dimensional fetish’, as Mulvey writes (a thought which will be later echoed in Nina Power’s 2009 book One Dimensional Woman), the artists in Body Anxiety take this to its hysterical consequences, attempting to break the Master-Slave bond, making woman image AND bearer of the look. Let me return to the title for a moment. Anxiety, Sigmund Freud wrote, is neurotic fear, as distinct from real fear. So one is a reality, something tangible and worthy of our concern whereas the other sounds like is made up, accusation of fabrication (like hysteria). It is this last idea the show is trying to contend. The anxiety felt and displayed in these bodies, the imperative to conform to a certain standard and behaviour, the manipulation of femaleness in pornography, the shutting down of the woman’s voice are indeed neurotic, but not because of it they are less real. As a body of work, the exhibition is convincing and raises clear issues around female empowerment, agency and exploitation, and how these are linked to flesh. Converting the anxiety into an intelligible fear that can be stood up against, as these artists do, might be the first step towards overcoming it.