In the introduction of Civic Radar, editor Peter Weibel sets out the motivation, layout and journey of the book. This first comprehensive monograph of Lynn Hershman Leeson’s artistic career, spanning across five decades. It must have been a dizzying publication to work on, when compiling her pioneering work in the fields of photography, video, film, performance, installation, and interactive and net-based media art. It is noteworthy that Hershman Leeson collaborated in its production. One feels her personal involvement in the book – its richness, care and detail, shows in its nearly 400 pages, and approximately 500 illustrations. It also features supporting texts by other writers, curators, theorists, and artists, such as: Andreas Beitin, Pamela Lee, Peggy Phelan, Ruby Rich, Jeffrey Schnapp, Kyle Stephan, Kristine Stiles, Tilda Swinton, Peter Weibel and interview by Hou Hanru and Laura Poitras with the artist.

“I try to live in the present, because most people live in the past. If you live in the present, most people think you live in the future, because they don’t know what happens in their own time.” Lynn Hershman Leeson.

Lynn Hershman Leeson has pioneered uses of new technologies, recognized as key to the workings of our society today. She tackles the big questions surrounding: identity in a time of mass, overpowering consumerism; privacy in an era of surveillance; the interfacing of humans and machines; the relationship between real and virtual worlds; and new bio-ethics surrounding practices such as growing parts of the human body from DNA samples. We can think of Hershman Leeson as a direct artistic descendant of Mary Shelley. Consider Shelley’s celebrated publication, Frankenstein: Prometheus Unbound, published in 1818, and its challenges towards macho revolutionaries of ‘reason’, and her critique of the misuses of science and technology by the patriarch. We can see strong parallels between both women. They are feminists, who have managed to find ways around (and to work with) traditional forms of dominant, patriarchal frameworks, so to express personal, creative and cultural identities, on their own terms.

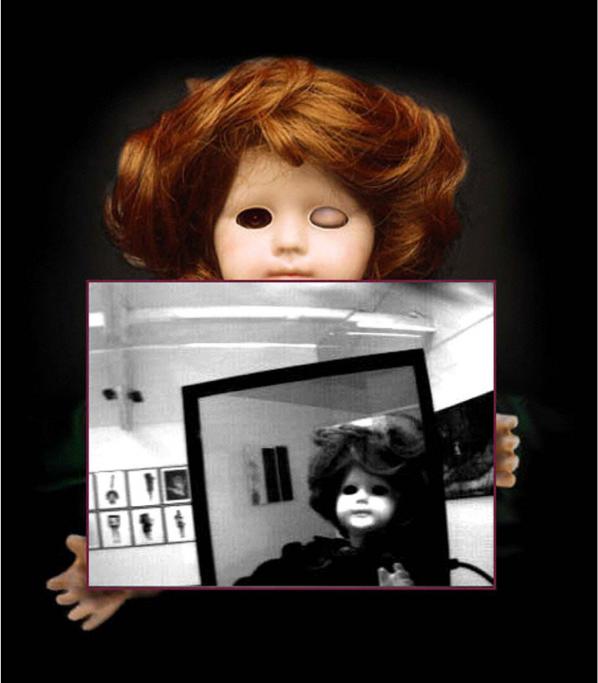

“Lynn Hershman Leeson’s mission statement seems to be that the body is a programmable software embedded in a changeable hardware. Therefore, she shows us so many hybrids and mutants, aliens and agents, actors and avatars, in real life and second life. From Dolls to clones, she demonstrates the paradox plurality of identities especially in the age of total observation.” [1] (Weibel 2016)

Hershman Leeson’s artistic process however does not keep its distance from the processes of science and technology. She leaps into the depths of our fears and unreservedly engulfs herself, and her imagination in their material influences and modifications. Like Donna Haraway, Hershman Leeson takes cyborgs, misfits, biology, mutation and transformation as her inspiration, contexts and materials. And also like Haraway, she playfully and critically owns concerns around science and technology, along with the ethical issues that may arise out of their continuously shifting, influences on society; and, thus not owned by or weighed down by them. Every work put forward by Hershman Leeson, is an experiment. Her interests and knowledge inspired by science and technology reflects her constant state of contemporariness. Her work directly correlates to breaking down systems of perceived values.

“Hershman Leeson confronted conventional gender roles and exposed the normative construction of gender identity. Some of her videos have included cross-dressers and transgender men and women, as in Double Cross Click Click (1995), and her assumed male pseudonyms at a time when the art world was dominated by men who mostly ignored women.” [2] (Beitin 2016)

Hershman Leeson’s art moves fluidly between different formats, contexts and disciplines. This of course is not easy to brand. The art market survives by promoting art that fits into particular roles and products that are easy to promote, predict and consume. The irony here is that the art world promotes the idea of itself as a site of novelty and insights, but in reality represents a deeply conservative culture. Some artists, Hershman Leeson is one of them, transcend the contemporary artworld norm and build alternative universes, contexts and identities, where the art is so investigatory and esoteric, traditional conventions are challenged.

When I interviewed Hershman Leeson last year for Furtherfield she talked about how she’d like to “eradicate censorship, and make more transparent the capitalistic underpinnings that are polluting access, value and visibility”. In the 70’s, she was the first artist working on a prison art project in San Quentin, and many of her early public art works “geared toward social change.” [3]

Civic Radar shows us that her work is not reduced to a singular, reflection of her own creative self. There is a wider story and it includes the voices of many others as part of the narrative of her life and her work, as well as reclaiming a history in a male dominated society.

We see reaffirmed a varied and dynamic history where she has been involved in strengthening the role of women in society, as part of an extension of her art process. One excellent example of this rich history is that over a period of 40 years she interviewed an extensive array of women artists, historians, activists, and critics who integrated personal and political content into their work. Then, some of that gathered material was made into a film project !Women Art Revolution, in 2010.

Lynn Hershman Leeson has not only achieved pioneering work as an artist, but also as filmmaker. She has collaborated with actor and Oscar winner Tilda Swinton in several feature films that have gone on to receive numerous awards at international film festivals on account of their outstanding quality and innovative themes. »Teknolust« is an absurd, amusing and scientifically highly topical science-fiction drama on the subjects of cyber-identities, biogenetics, gender constructions and sexual self-determination in the age of the Internet. The plot turns on the scientist Rosetta Stone (Tilda Swinton), who illegally produces three clones of herself. The artificial entities can only be distinguished by the color of their clothing and live in an enclosed cyberspace. Because they are dependent for survival on the male Y chromosome, Ruby, the femme fatale among the clones, goes in regular pursuit of men. Sexual contact with Ruby leads to impotence in her lovers as well as to an allergic reaction triggered by a computer virus which is transferable to human beings. The FBI becomes aware of the clone family’s machinations following the increased incidents of infection among men, and begins to investigate. Note*

Her work has crossed into many different fields and formats. Which includes: installations, videos, films, sculptures, robots, avatars, contracts, computer programs, photography, paintings, drawings, collages, browser based art, artificial intelligence, bio-matter, network communication systems and devices. Synthia Stock Ticker and Dollie Clones are just two examples that demonstrate how ahead she has been with her ideas and her integration of digital technologies into art. Synthia Stock Ticker, is a networked-based media artwork made in 2000. It refers to the stock ticker invented by Thomas Edison and is unusually prescient in its portrayal of the emotional life of global markets. Inside a glass casing sits a small monitor screen, showing a video of a woman character named Synthia. “When the market is up, the character dances and shops at Christian Dior: when the market is down, she chain smokes, has nightmares, and shops at Goodwill.” [4]

Again The Dollie Clones 1995-96 predate a contemporary artistic obsession with creeping surveillance. Two telerobotic dolls, Tillie the Telerobotic Doll and CyberRoberta, whose eyes have been replaced with cameras. Each doll has a website that allows users to view the images taken by the webcams and click on an “eyecon” to telerobotically turn the doll’s head 180 degrees to survey the gallery.

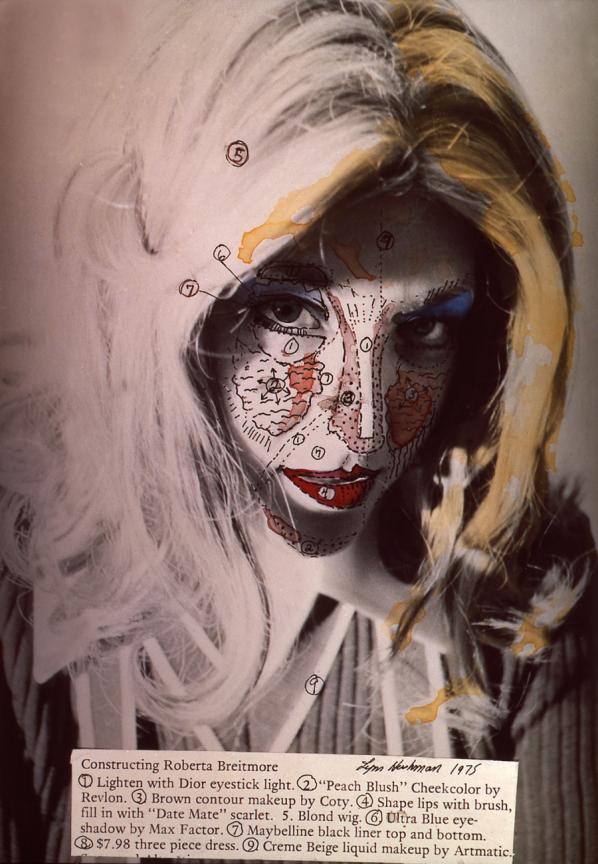

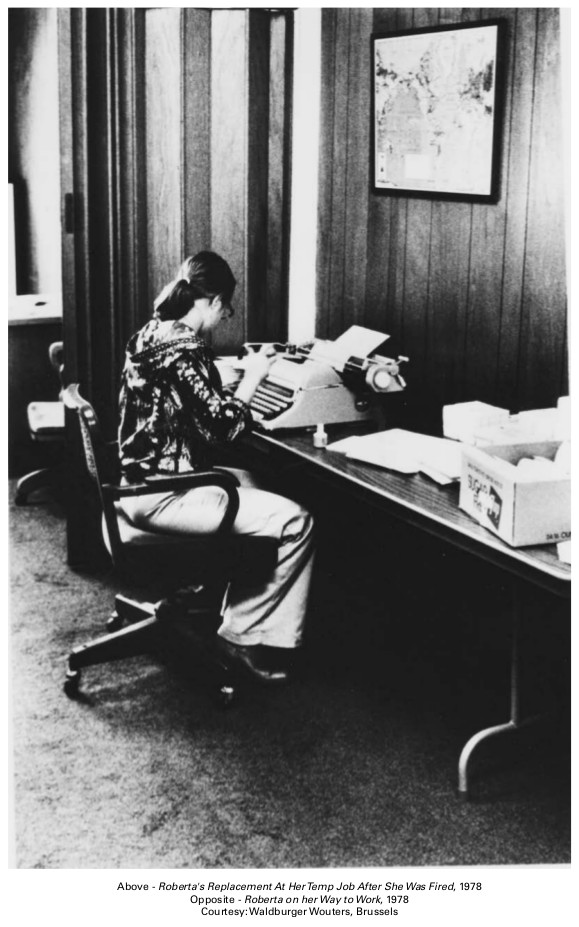

Hershman Leeson’s most prominent performance work was as another woman, Roberta Breitmore. This elaborate alter ego existed between 1973 and 1978. The Breitmore character was well developed, possessing different behaviors and attitudes to Hershman Leeson’s own personal identity. Roberta Breitmore had her own handwriting, clothing, wig, makeup, driver’s license, apartment, psychologist, bank account, credit cards, acquaintances, life story, and adventures. Hershman Leeson took the audacious leap and sporadically became Roberta Breitmore for 5 years. Other women also lived as Roberta Breitmore and sometimes simultaneously. [5]

“Hershman Leeson hired three additional performers, all women, to play Roberta. They wore costumes identical to the ones Hershman Leeson herself wore, and they treated Roberta essentially as a professional (albeit part-time) gig. They undertook some of Roberta Breitmore’s correspondence and went on some of her dates (which were documented in photos and audio recordings). Eventually, Hershman Leeson stopped enacting Breitmore, reducing the instantiations of Roberta Breitmore from 4 to 3.” [6] (LaFarge 2007)

The spirit of Hershman Leeson’s radical art persona can be seen in younger, contemporary artists today. For instance, Heath Bunting’s Identity Kits, part of his larger The Status Project consist of various items, personal business cards, library cards, a national railcard, T-Mobile top-up card, national lottery card and much more. “They take a few months to compile each of them because they are actual items that everybody uses in their everyday lives, involving evidence of identity. There is also a charge for the package of 500.00 GBP, which is cheap for a new identity.” [7] (Garrett 2014) Then we have Karen Blissett, an Internet artist who suddenly decided to go multiple by opening up all of her email, Twitter, Facebook and Google accounts to many different women around the world. “A torrent of provocative, poetic, and often contradictory voices issued proclamations, made auto portraits, and shared psalm-like meditations on her existential transformation; distributed across online platforms and social spaces, in text, image and video.” [8] (Catlow 2014)

Towards the end of Civic Radar a collection of pages show us various images of the exhibition by the same name at the ZKM Museum of Contemporary Art, in Germany 2014. When viewing the images of her work in the large gallery spaces you realize the scale of it all, and how substantial her work is.

Moving on after the images of the works in ZKM, there is a selection of Hershman Leeson’s texts written, from 1984 and 2014. These writings, take us through different stages of her career, revealing ideas and intentions behind much of her work and also some of the work included in the publication. In the last paragraph of the last text in a short essay, titled The Terror of Immortality she writes about the contexts that have given rise to her most recent work. “As organic printing and DNA manipulation reshapes the identities of newly manipulated organisms, so too the culture of absorbed surveillance has dynamically shifted. In the next 100 years, the materials used to create DNA will become increasingly distributed and hybridized. The implications of this research include not only the creation of a sustainable planet of hybrid life forms that can survive a sixth extinction and incorporate into to its existence a morally responsible future.” (Leeson 2016)

This book is a profound read, offering an insight to this generous and profound artists’ fantastical journey in an era marked by accelerating change. And what’s so amazing is that the content, the narratives, and the histories, are real. It is an Aladdin’s Cave of rich, exceptional artworks, flowing with brilliant ideas. Hershman Leeson has had her finger right on the pulse of what’s relevant in the world for a long time, and transmuted the knowledge she unearths in her examination of identity, feminism, science, technology and more into her own artistic language.

Her work is way ahead of most contemporary artists showing now. This book should be read everywhere. Not just because it features great art, but also because features a woman with a great mind. I am not a fan of the words genius or masterpiece; I find them tiresome terms reflecting a form of male domination over women and the non-privileged classes. Yet, after spending time with Civic Radar, I cannot help myself thinking that I have just witnessed something equivalent without the negative baggage attached.

*Text from ZKM – Teknolust. With Lynn Hershman Leeson at the cinema.

http://zkm.de/en/event/2015/03/teknolust-with-lynn-hershman-leeson-at-the-cinema

In 2015, ZKM in cooperation with the Deichtorhallen Hamburg / Sammlung Falckenberg exhibited the first comprehensive retrospective of Leeson’s work, including her most recent productions of art. Last year Modern Art Oxford hosted a major solo exhibition of her work Origins of a Species, Part 2 and she also has work in The Electronic Superhighway, at Whitechapel Gallery, in London.

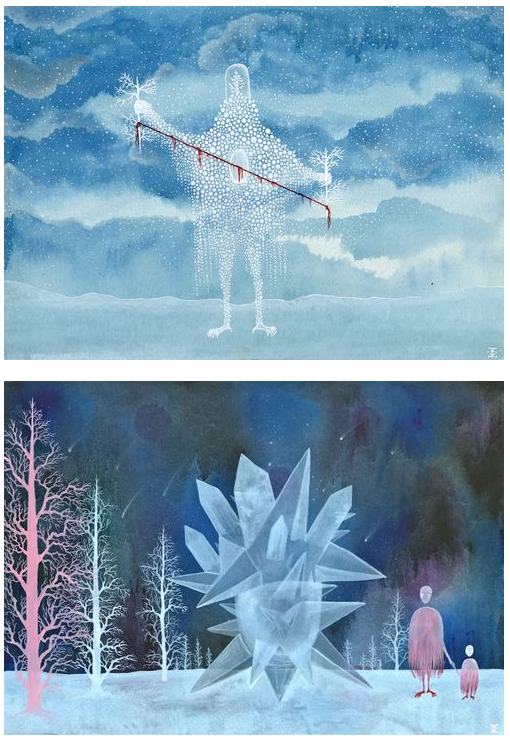

In a mysterious pine forest, inhabited by half-human, half-animal creatures, the dismembered white body of a furry god is slowly reassembled. A creature with the head of a black bear pulls down the decapitated body from a tall rock. A red-robed character with a crimson wolf’s face, decorated with sharp white teeth, fetches the severed head. Another brings the eyeballs; another, the skull. Finally, in an illuminated multi-coloured tent glowing in the darkness of the woods, a character with the head of a triceratops and a cloak of many-coloured feathers performs a ritual involving magic crystals and a dead bird doused in blood. The film ends with a single glimpse of the white god’s foot, planted in a field of snow, sufficient to suggest that he, she or it has been brought back to life.

I first came across Magic Blood Machine as one of the staff picks on the Vimeo site in October 2014. It was on a list of spooky videos for Hallowe’en. The rest of them looked fairly conventional, but the still for Magic Blood Machine stood out: the red-robed character from the film standing amongst dark pine trees, looking a bit like a Roman Catholic Cardinal, a bit like Anubis – the jackal-headed god of Egyptian mythology – and a bit like Reynard the Fox. When I watched the video, I was struck by the same mixture of associations: it seemed to combine elements of the crucifiction and resurrection of Jesus, the dismemberment and restoration of Osiris, and the Green Man myth. Folk-stories, mythology, the occult, the macabre, and even a touch of science fiction were all in the mix. But its visual design, filmic and narrative qualities were just as striking. There are no words spoken, and the pace is slow, but nevertheless the film exerts a powerful compulsion, partly because of the expertise with which each sequence unfolds and leads us to the next, and partly because it’s so full of unanswered questions. The actions of the strange characters in the pine forest seem charged with hidden meaning, as do the characters themselves, sharply-differentiated from one another as they are by virtue of the brilliant costume-design. There is a strong sense of place in the outdoor filming, and a strong sense of the tactile as well: the way the characters stroke the dead god’s fur, fondle the magic crystals or pour blood over the breast of the dead bird, for example. And despite the use of expressionless masks, there are moments of powerful emotion. When the red creature, having retrieved the white god’s severed head, lays it next to the rest of the body and then sits beside the corpse, holding its hand, it eloquently conveys a sense of love and grief.

Magic Blood Machine was made by a Norwegian artist and film-maker called Ingrid Torvund, in close collaboration with her partner Jonas Mailand, and with music by Jan Erik Mikalsen. It took three years to make (2009-12), and a sequel called When I Go Out I Bleed Magic – which Ingrid describes as the second part of a trilogy – was released earlier in 2015. For me, When I Go Out I Bleed Magic is less compelling than its predecessor, but if anything the design of the film, in terms of costumes and settings, is even more impressive. Ingrid makes almost all the costumes and props herself, and they are works of art in their own right, some of which she has exhibited separately. She has also exhibited her drawings and published many of them in a book, again with the title When I Go Out I Bleed Magic.

Ingrid’s work strikes me as an example of the enabling power of the Web, which can sometimes allow genuinely original artists to reach international audiences they would have found it very difficult to access at any time before the 1990s. It also allows the likes of me to get in touch and start up a conversation out of the blue. Accordingly, I contacted Ingrid via email to ask about her work, and the results are reproduced below.

Edward Picot: Can I ask you about the making of the costumes and props for your films?

Ingrid Torvund: I make the costumes and props myself mostly, sometimes I get some help from my friends and family, if it´s large set pieces and so on. I like to take my time making these things, it`s a slow process but it´s one of these things that makes life worth living.

EP: Were you at art school, and if so did you study art, textiles, film or all three?

IT: I went to Oslo National Academy of the Arts,where I took a bachelor degree in fine art. While I was there I made my first short, “Magic Blood Machine“, and I worked on it for three years. I took courses in film, philosophy and many other subjects.

EP: Can you describe your creative process a little bit? Do you start off with an idea for a story, or with sketches in your sketchbook?

IT: it’s really random how I find inspiration, but sometimes I find a nice tactile material that I want to work with and I start by just trying out how and then I can make something that gives the audience the same feeling I got when I first saw it. And sometimes I get a picture in my head of a scene I want to make and then I try to figure out how to make it, then I draw it (but not very detailed and not very good 🙂

I wish I could say I plan out projects better, but I usually just make what I want to make. Over the years the planning of the filmprojects has become more detailed, but this is because I have to [plan things out] when I apply for funding and it’s a real creative killer.

For the last film “When I Go Out I Bleed Magic” we (me and Jonas) made a long storyboard with many scenes, but in the end we didn’t get to make them all due to lack of funding, lack of time and plain exhaustion.

EP: You say you like to take your time making the costumes, props and so forth. Does this mean that your ideas about the film you’re going to make grow quite slowly and organically as you’re in the process of making things?

IT: Yes it does, it’s a long process and I usually try to finish one little part at a time: a costume, a set piece and so forth. But when the time comes to shoot the scene, I have to but all the pieces together, and then I have a time limit. In the two films I’ve made so far I’ve been borrowing my dad’s place, because there I have the space to actually build a little studio in the summer. But since this is his workplace normally, I have to clean it out before they come back from their holiday 🙂 So the summer is a really intense period in the year for me and I have to plan it out more, due to the fact that when I go to work there, I can’t get away, so I must buy all the materials I need before I go. I don’t have a car or a licence and it’s in the countryside. We do have a little boat that I can take to the grocery store 🙂

EP: You mention you’ve got a boat – and lo and behold, there’s the red character rowing a boat in Magic Blood Machine. I’m guessing from this that the boat in the film is your own boat, and the lake which appears in both films is the lake where you live.

IT: Yes, most of the places in the movies are from around where I grew up. I also think that it’s important to find inspiration from real and often personal things in life. it feels important to me to know that the project has some kind of root in something real. At my last exhibition my mother gave me some very old school books that I had made some drawings in, and it was almost disturbing how much some of them resembled some of my more current drawings!

EP: Let me ask you about Jonas. How do you work with him? How did you get to know each other and work together, and do you write together, or does he do the camerawork while you put on the costumes and do the acting?

IT: I met Jonas while we were going to an art school in Oslo seven years ago, at the time I was already making characters and installations and we started to date while I was building a forest installation inside a room. He has always had great interest for films and making them, and at that point I was thinking of trying to bring my characters to life by making them into costumes I could wear. After a year we started working on Magic Blood Machine. From that point he has done all the camerawork, while I do all the costumes, set pieces and “acting”. We usually edit the films together and sometimes we make an edit each and then compare them, and choose what we think works the best. I’ve been asked before how we collaborate on these projects and sometimes I find it a little difficult to answer, because we live and work together and we have no rules on who does what in these films. But I do know I spend most of my time thinking or working on these films and Jonas takes part in that if I ask him to. Without him I would not be able to make films like these and my life would suck.

EP: Lastly, would you like to say a bit about the mixture of mythological references in your films?

IT: I have always been fascinated with the mixture of pagan and Christian culture. When I was young I found a book called “Norske Hexeformularer og magiske opskrifter”: it’s a collection of spells and magical recepies from 1600-1900. The spells are collected from small black books found throughout the country, often hidden away. Some would put them under the church steps in an attempt to get rid of them. My films are inspired by these rituals and the conflict between nature and religion. I grew up going to church a lot and I think the mix of church and folklore is something I use as inspiration when I make films.

I think I find the history of how people lived and their traditions even more fascinating then fairy tales, for example people used to think that their newborn babies sometimes got exchanged with a person from under the earth.The child then got some kind of physical change,like a weird growth or huge eyes or it suddenly looks very old. The only way to fix it was to lure the under earth person to tell you their real age. You did this by doing weird and absurd stuff, like making porridge in an eggshell or making blood sausage in an catskin. Then it would suddenly tell you how old it was and then it would die. Leaving a little lump of ash and bones…

More information about Ingrid Torvund can be found on her website, http://torvund.tumblr.com/. Magic Blood Machine is on Vimeo at https://vimeo.com/44936472, and When I Go Out I Bleed Magic is also on Vimeo, at https://vimeo.com/44936472.

‘RE / PRE / SENT / PAST’, an exhibition featuring works by media artist Markus Soukup as part of Furtherfield Clear Spots programme, explores different phenomena from dreamscapes to long distance travel recordings, as well as attempted considerations of societal change in relation to technological developments.

It brings together fragments of subjective experiences related to contemporary everyday existence, which were translated and transformed into ‘perceivable outputs’ by using different digital techniques. The screen or the physical object as output constitutes an interface, where perceptual experiences of the spectator intermix with the intentions of expression.

The wonders of perception are connected to imagination processes and a continuous stream of individual interpretation that play with the question of what defines objective reality.

Markus Soukup is a media, video and sound artist living and working in London since 2012.

In general he considers the process of making work as an exploration of how an object, image or moving image can communicate its intended content or expression by still enabling freedom of interpretation on realistic and abstract levels.

He is fascinated by the infinity of possibilities and starting points, which the work with moving images provides. Since the end of the 90s he produces videos, 2D and 3D animations investigating the narrative, expressive, poetic and aesthetic potentials of this time-based medium.

A series to be continued investigates language and its structure by de-constructing content or flow, breaking it into parts and reconstructing it on a time based level. Other areas of his work incorporate digital photography and typography, graphic and interactive design, field recordings and electronic music.

His work has been shown in local, national and international exhibitions and festivals, for instance at the 11th international Media Art Biennale WRO 05 (Wroclaw, Poland, 2005), NEXT UP at the Bluecoat Liverpool (2008), the 10th Seoul International New Media Festival (Republic of Korea, 2010) and the Liverpool Biennial 2010.

In 2011 he was awarded the Liverpool Art Prize. As a result his work was shown in the ‘Elements & Satellites’ exhibition at the Walker Art Gallery, part of National Museums Liverpool in 2012.

In 2013 he was commissioned by Metal Culture to produce the video installation Strata for the ‘STILL, conflict, conservation & contemplation’ exhibition curated by Simon Poulter at City Gallery Peterborough.

Recent exhibitions include Infinite Separation, part of ‘Art:Language:Location’ at Anglia Ruskin Gallery Cambridge, and Disjointed at Museum Ex Teresa Arte Actual in Mexico City.

+ More information:

www.toofastproductions.co.uk

Furtherfield Gallery

McKenzie Pavilion, Finsbury Park

London N4 2NQ

T: +44 (0)20 8802 2827

E: info@furtherfield.org

Furtherfield Gallery is supported by Haringey Council and Arts Council England.