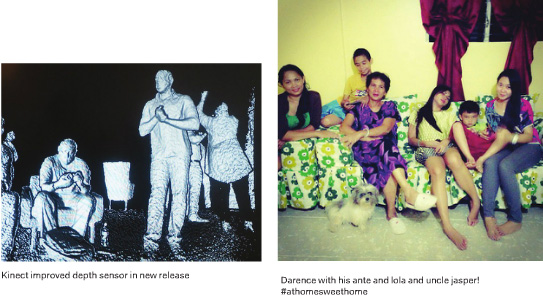

Featured image: By Instagram users lynellspencer and banditqueen555

I’ve been thinking about the idea of home a lot recently. I’ve been traveling over three continents for the last 6 months, living out of hostels, surfing friend’s couches, and even staying in local homes through Couchsurfing or personal connections. In terms of my home, I’ve grown comfortable with no privacy, sleeping in a room of strangers with only a tiny locked box for security. While I knew in my head the contemporary home is always shifting, I didn’t start considering the impact of that until my own housing situation became so erratic.

So I was excited to reflect further on the homes when the design research collaborative Space Caviar released a book of commissioned essays entitled, SQM: The Quantified Home. The essays examine how the romantic idea of the home is increasingly in tension with global market forces, zoning laws, new technologies, surveillance, war, and much more. The book was commissioned by Biennale Interieur and was part of Space Caviar’s program, “The Home Does Not Exist,” which premiered at the Biennale Interieur in Belgium in October of last year.

“Industry people today don’t actually want the home of the future. What they want is the homeowner of the future, as the kind of completely consumer-aware, Amazon-livestock guy… They don’t care what the shape of the house is, they just want the data flows in and out.” – Bruce Sterling, (pg. 236)

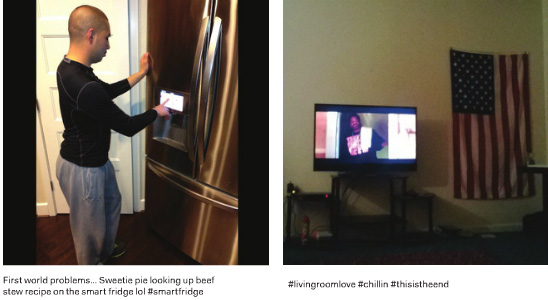

In his essay, Bruce Sterling asks us how the architecture and architects of the home will be disrupted – like the music and publishing industries were disrupted – for data optimization? As we’ve done for social media, we’re opening up our homes to private companies for the sake of security and ease. We’re putting security cameras in our children’s bedrooms and connecting our home to the cloud with devices such as Amazon Echo. How will the home as networked site look when created to produce as much advertising data as possible? How can a home look more like an Amazon warehouse?

In the networked home of the future, will we enter a Facebook-like power relationship, willingly rendering all our most private moments visible to marketers for a tax break or a free networked fridge? It sadly doesn’t sound too unlikely to me. SQM: The Quantified Home sets up a history and context to considering the realities of this kind of future home, making the clear complex data and politics already intersecting within our home.

Much of this opening up of the home is economically focused. Given the financial collapse of 2008 and subsequent austerity measures around the world, of which all but the mega-wealthy are still reeling from, we’ve been forced to use our homes as economic tools of investment as much as private spaces for family and loved ones. An investment which fewer and fewer people can afford to make. If architecture, homes, and even cities follow the trend of social media’s economic disparity – exchanging some free services for huge swaths of powerful and valuable data – it’s only going to get worse.

Selling acceptable looking cheap furniture that can barely survive its own assembly, Ikea is a perfect response to a generation that cannot afford a home. As career security grows more precarious, we’re increasingly moving cities and jobs, with Airbnb as a life raft for homeowners who can’t afford rent, and renters who can’t afford a home. The romantic ideas of “home” are collapsing all around us. As Alexandra Lange, author of Writing about Architecture: Mastering the Language of Buildings and Cities, notes, our Pinterests are filled with items we will never buy for homes we can no longer afford.

In, “The Commodification of Everything,” Dan Hill, the executive director of Futures at the UK’s Future Cities Catapult, looks at Marc Andreessen’s notion that, “software is eating the world,” and applies it to Airbnb and resident-led emergent urban interventions in Finland. While some celebrate often left-of-legal urban interventions, many of the same group cries foul when corporations like Airbnb do the same.

Hill writes, “It took Hilton a century to construct all of their hotels, brick by brick; Airbnb came along, armed only with software, and in six years created more without laying a brick.” (pg. 219) Hill asks us to further investigate how to use software in a civic way, protecting and enabling local culture and economies for the benefit of everyone. Hill writes that software “is eating the world, and it is only just booting up. Our response to that, as citizens and cities, will determine whether it does so for public good or for private gain.” (pg. 223)

So while the home is becoming a more fluid space, this predominately suits businesses or people like me because I have the freedom and privilege to move easily and earn a living wherever I have internet. Making housing more responsive to individual needs is nice advertising, but ignores larger housing markets and market forces all of us are subjected to.

Now, after reading this book and 6 months of travel with at least 6 more months to go, my idea of the home has shifted to be understood mostly in relation to family and friends. Moving through many different architecture styles, cultures, customs, and living situations have made me care less about the physical space of the home. However, this means that as the contemporary home becomes a site of surveillance, responsive, and transparentin relation to corporations and often governmental organizations, the contemporary home will place these networked spheres between us and those we most cherish.

Our most intimate settings – be it a home or an Airbnb room – now have corporations sitting right next to us. Just as we know you shouldn’t share anything you don’t want everyone to know on Facebook, in the future, we now know not to talk in front of your smart TV. The home may be the final site of privacy in modern cities yet many are actively sacrificing that privacy for a sense of security or for cool new products whose terms and conditions we never fully grasped.

Conversely, instead of placing ads between a couple cuddling on their networked bed of the future, the networked home is equally likely to put our entire social network into the bed with us in hopes of more clicks. We already see how social networks can favor clicks over meaningful connection. Joanne McNeil’s essay. “Happy Birthday,” continues a progression we’re already seeing to an always-on extreme where our birthdays are reduced to spam-like events where everyone we ever met and every object we encounter spews “Happy Birthday” ad nauseam.

This is of course a product of the advertising model of which most everything online is reliant on. Why would that change when the internet moves into your home? Indeed we already ask for this as 80% of 18 to 44 year olds check our phones first thing upon awakening. Now just turn your bed into the phone.

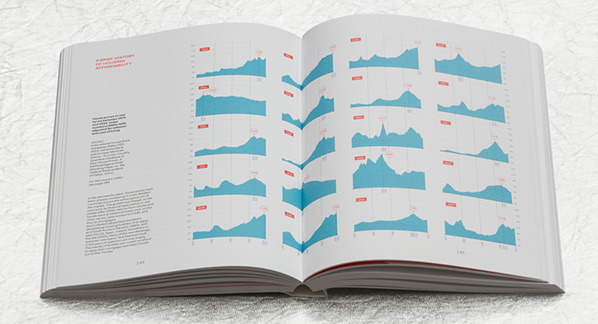

While networks moving into our home is cause for alarm, what was most startling to me about SQM: The Quantified Home, was the extent to which the home is already a site of many networked relationships between the city, few of which we control or are meaningfully transparent to the average homeowner. In “Postcode Demographics” Joseph Grima and Jonathan Nicholls discuss Acorn, an early program quantifying housing markets in the England. Using 60 metrics of classifications, Nicholls helped quantify neighborhoods for real-estate developers, homeowners, taxation, and more. The introduction of postal codes further quantified neighborhoods in a way likely many find helpful yet can lead to a kind of data lock-in. As these methods of quantification grow more complex, and the ramifications larger, the possibility of residents transcending their zip codes grows dimmer. We see this problem with funding of public schools in the states.

While we continue to connect to our homes and to each other in new ways, if those connections continue to benefit the Googles of the world the most, we’re in for trouble. Turning your home transparent to them and forgetting the place of the home within larger societal and civic concerns is dangerously shortsighted and will only benefit the big businesses. As Hill writes, whether these changes are to be net positive depends, “on how much we care about the idea of the city as a public good, how adept we are at absorbing and redirecting disruptive forces for civic returns.” (pg. 223)