How do we collectively care for Finsbury Park?

Which people and which creatures?

What part would you like to play?

We invite you to join us at Furtherfield to explore these questions. Together we will make and play a game with various characters, imagining Finsbury Park in 2025 as the place where a global multispecies revolution begins – and changes the world forever.

How can you get involved?

Originally planned for the Summer of 2020, the first community meetings took place in March, however Covid-19 has paused the development of this project. If you would like to work with the game designers Cade and Ruth, and each other, from Furtherfield Commons and online email Ruth at ruthcatlow [at] gmail.com.

About The Treaty of Finsbury Park 2025

At Summer Solstice a visiting delegation of artists, equipped with park blueprints, bylaws, data-sources, historical documents, and policies, will work with local envoys who present testimony from the many human and non-human lives of the park. Together, the two parties will work to mutually devise a treaty to govern the future actions of multispecies park users, turning the park itself into a “love machine”. This culminates in a public ceremonial treaty signing event.

With a bit of luck the game, final treaty, audio recordings, photographs, and resulting artistic responses are now planned for development and exhibition at Furtherfield in the Summer of 2021. Part role play game, part participatory performance, this event will be based at Furtherfield Commons and across Finsbury Park for three days at the Summer Solstice.

The Treaty of Finsbury Park 2025: On systems, ecologies as networks, colonialism and seizing rituals of power.

Read the essay

Hear the discussion between Ruth and Cade on the Furtherfield Podcast

Illustration by Sajan Rai.

If you have any questions or would like more information email Ruth at ruthcatlow [at] gmail.com.

This project is supported by CreaTures – Creative Practices for Transformational Futures. CreaTures project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 870759. The content presented represents the views of the authors, and the European Commission has no liability in respect of the content.

In partnership with AntiUniversity

Whether you smelt it, mine it, burn it, breathe it, or shove it up your ass the result is the same: addiction.

Addiction is defined as a chronic, relapsing earthly disease that is characterized by compulsive seeking and use of earth products, despite harmful consequences. It is considered a brain disease because humankind changes the earth—they change its structure and how it works.

Soft Sickness is a one evening/one day workshop hosted by the research project Shift Register exploring the signs, symptoms, circulations, exchanges, consumptions, dependencies, and management implicit in the multifarious and pathological dependence on the earth which is now named by that word “Anthropocene”. Earthly addictions produce quantified-earth self-portraiture, GIS co-dependencies, and all other variants of planetary narcissism. Earth-scale sensor systems and media networks, swathing the planet in information about itself, are unveiled with media from on- and off-planet earth science field-stations and reflections thereupon. Dependencies bring anxieties about the impending doom of resource dearths to come. People manage these anxieties with new psychotropic medications, whereas artists represent and markets bet on them, against the health of the earth and its living bodies.

Soft Sickness divines the earth lines of the often contradictory ingestion of and repeating addiction to the earth and its productions, data, memory — its circulations, seasons and natures, to the plants, the mushrooms and the animals, to fossil fuels, metals, to liquid screens and smogged surfaces, to longevity and, finally, to the real. To the thing and things which we cannot help doing (things to). To compulsively consume (the earth) is to eat and subsequently to excrete ourselves, humankind, and this cycle can be termed addiction. We feed from the earth, feeding back to the earth a world and mind-changing chemistry.

During the workshop, participants and invited guests will discuss, map, extract, ingest and excrete relations of local earth manifested in Finsbury Park in North London. Plant and pharmaceutical toxicities/ psycho-pharmacologies, poison cures, geophagic gastronomics, esoteric pollution sensing and embrace, and the invention and embedding of folkloric and human to non-human ecologies constitute parts of this invitation. We will gather psycho-active dew, imagine tales for the mole people, bake bread for crows, and make the earthworlds flesh.

We wish to develop contemporary rituals articulating the polarised and overgrown junk-tions of shamanic spirit journeyings with addiction managements; cold kicking the earth habit or indulging absolutely in the (cannibal/capital) undergrounds and (fairie) overgrounds.

SHIFT REGISTER is a research project investigating how technological and infrastructural activities have made Earth into a planetary laboratory. The project maps and activates local dynamics and material shifts between human, earthly and planetary bodies and temporalities. Contemporary, mainstream science and technology are intersected with other knowledge systems to attempt a reconfiguration of relations between humans and the earth. SHIFT REGISTER is Jamie Allen, Martin Howse, Merle Ibach, Jonathan Kemp and Martin Sulzer at the Critical Media Lab, Basel.

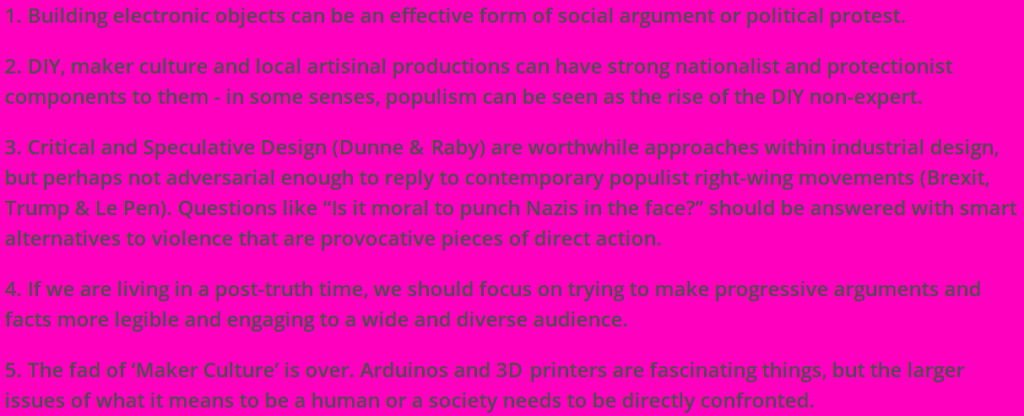

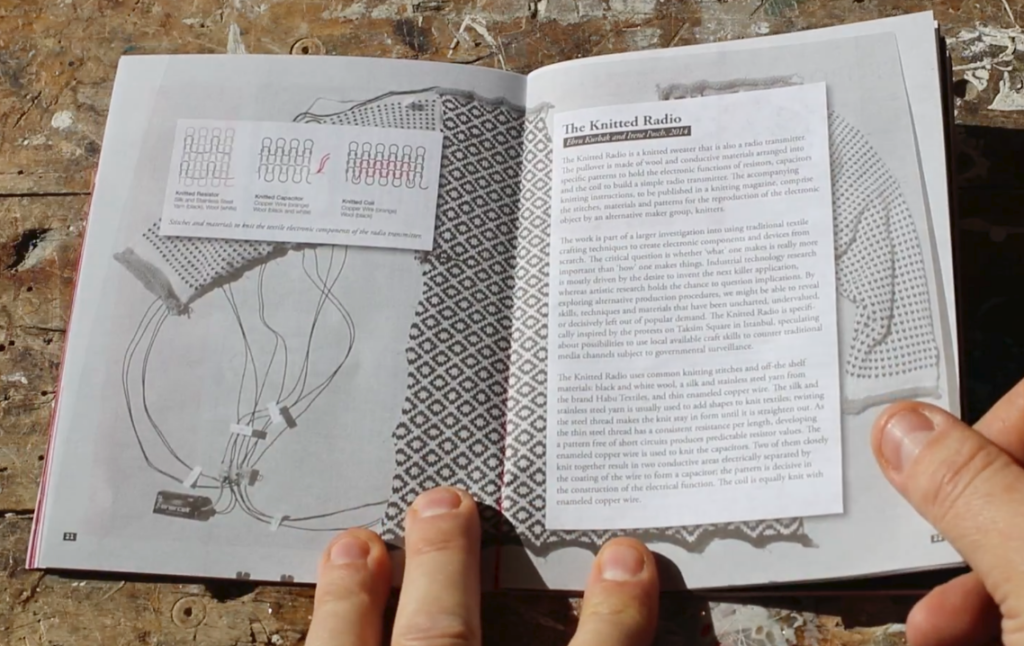

Disobedient Electronics: Protest is a limited edition publishing project that highlights confrontational work from industrial designers, electronic artists, hackers and makers from 10 countries that disobey conventions. Topics include the wage gap between women and men, the objectification of women’s bodies, gender stereotypes, wearable electronics as a form of protest, robotic forms of protest, counter-government-surveillance and privacy tools, and devices designed to improve an understanding of climate change.

I was one of the lucky few to receive a hard copy of this fine little zine, a handmade limited edition of 300, put together by Canadian artist & researcher Garnet Hertz. It features 24 contributions of critical art & design, many of which taking a strong stand on feminism and surveillance /privacy issues, indispensable in current debate. Hertz initiated this publication in response to post-truth politics, in itself a notion shrugged off by populist drivel – “Politicians have always lied.” – Ptp- strategies involve the removal of scientific context from popular claims in order to comfort the masses in turbulent times of change. Such trends are noticeable in culture and thus in the DIY- movement too. After a disappointing visit at a maker’s fair, which essentially promoted the aesthetic design of blinking LEDs and the 3D-printing of decorative junk in an overall atmosphere of relentless marketing, the manifesto of Disobedient Electronics caught my attention, reflecting my impressions accordingly.

Decline of culture becomes visible as ‘popular’ themes such as sustainability or integration policies are readily adopted but actually serve as mere buzzwords to increase the marketability of events and products. Since it became profitable to sell electronic boards and a variety of accessory components, the prosumer (Ratto, 2012) is bound to available materials and building instructions and not encouraged to experiment or imagine alternatives to already available commercial design. Therefore many important layers of technology get ignored or regarded as not worth exploring due to the fetishisation of the final result. Although focus should be on action oriented making, tactile objects /installations are important when linguistics fail. We have already incorporated digital structures in every social aspect of our lives and it is difficult to observe let alone express them.

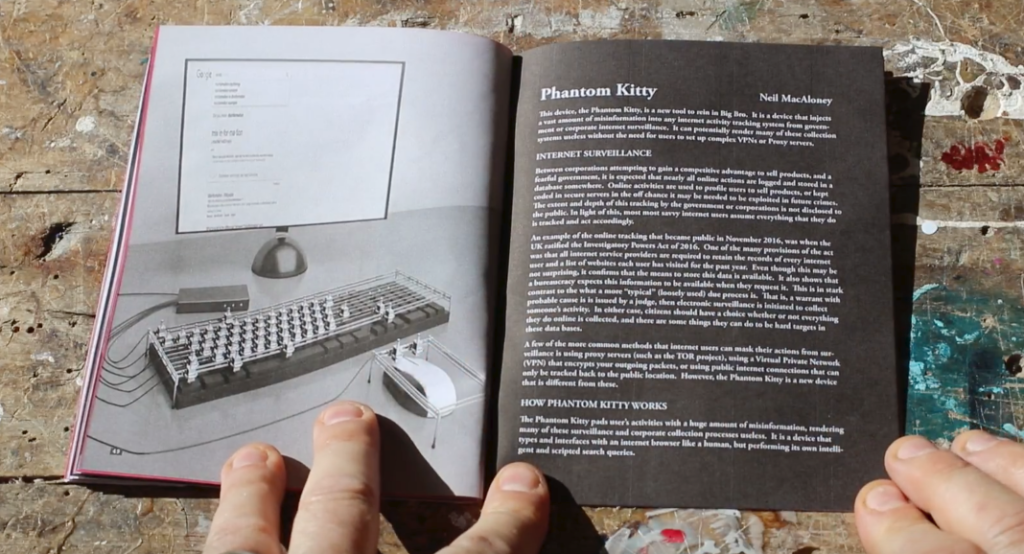

The book treasures the craft of DIY technology development, notably in the surveillance /privacy sector, and highlights the pressing need for knowledge in light of the technological advantage of those in power. Backlash provides us with an educational protest kit, including devices for off grid communication and bugging defence. These are functional but not necessarily designed for situations of conflict, rather for inciting a relevant debate among the general public. Phantom Kitty (work in progress) defies spying by authorities without a warrant and the enforced quantification of humans based on evaluations of online activity. It produces arbitrary noise when the user goes offline to obfuscate browsing habits and it is possible to integrate machine learning algorithms at a later stage, which could mimic or create identity patterns. Phantom Kitty features a stunning mechanical rack for keyboard and mouse operation, fed by a program executing search queries and the access of webpages. The project draws on the eeriness of neither knowing to what extent gathered data is exploited, nor against which parameters and targets it is set.

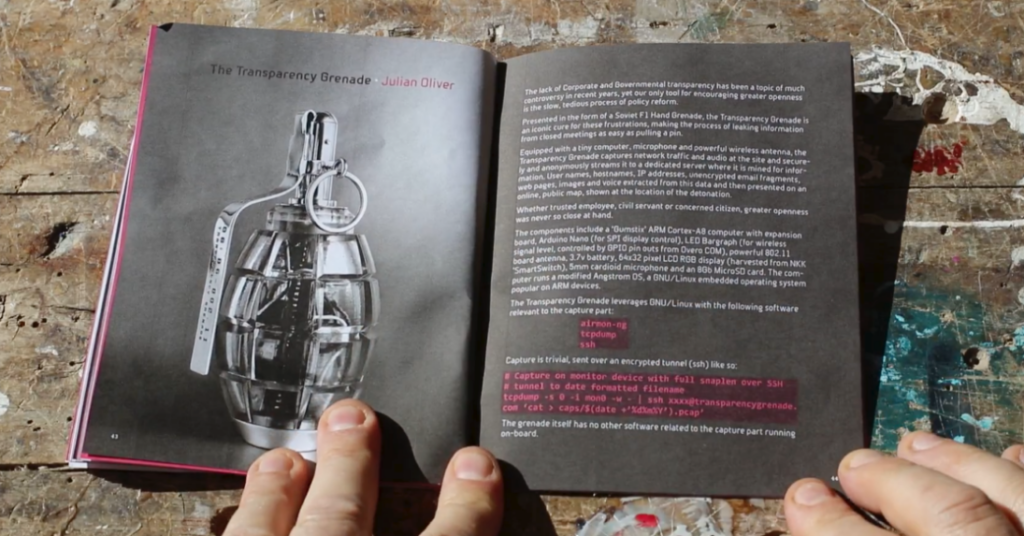

Completely left in the dark about the full scope of exercised control and entailing consequences The transparency grenade by Julian Oliver reminds us that citizens have a right to openness too. The promise of “making the process of leaking information from closed meetings as easy as pulling a pin” is tempting, and in contrast to the opaqueness of corporate and governmental policies, the artwork, other than claiming transparency, is representing it, in its aesthetics, open source software and in the thorough documentation of its engineering process.

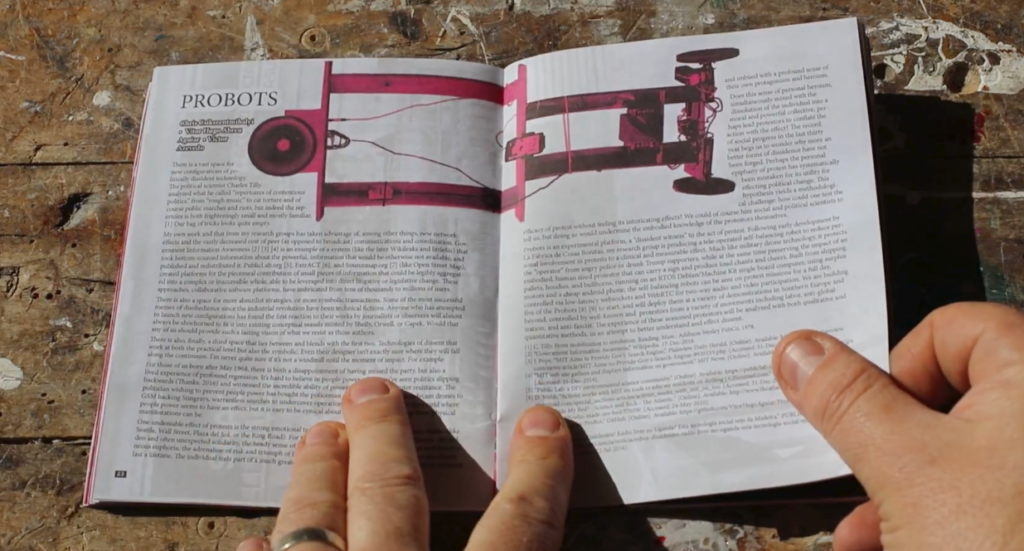

The well written accompanying text of one of my favourite projects PROBOTS describes effective works as “technologies of dissent that work at both the practical level but also the symbolic”, by all means valid for those involved making this book, albeit associating with a manifold of disciplines. The tele-operated protest robot certainly meet those demands and can be sent out by the precarious worker as an answer to the efficiency of contemporary policing, simultaneously a metaphor for the limited potential in the act of present-day corporeal protest. The silencing of political resistance happens far beyond the streets and PROBOTS makes an extraordinary research tool for investigating the organisational power of technology, which prevents social progress already from the outset.

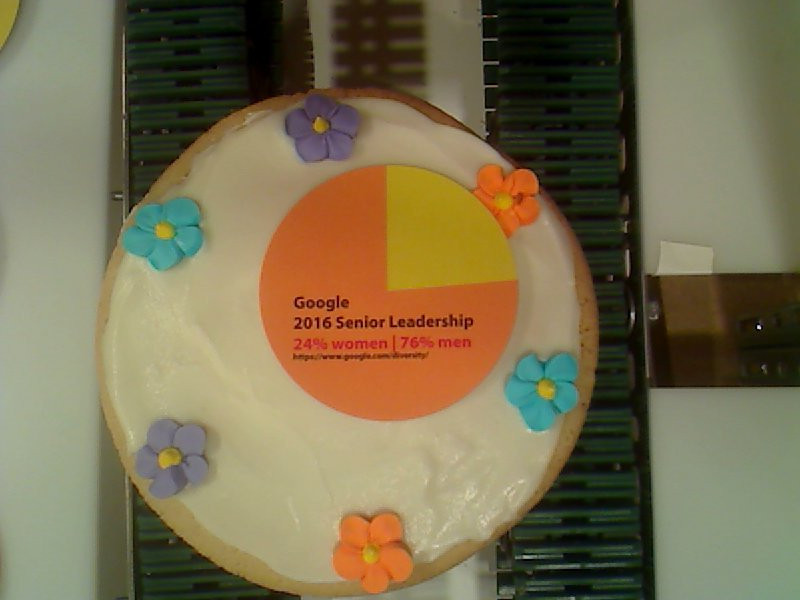

I’ve only recently discovered that e-textiles is not the same as smart clothing. It is a discipline, focusing on the act of making rather than the actual result, albeit in this case impressive too. The makers of The Knitted Radio approached the craft of knitting and electronics without economic reasoning, a factor which primarily informs the engineering process in industrial design. The liberation from conventional standards brought about alternative forms and methods, that is a sweater that also functions as a FM radio transmitter and the skill to knit electronic components /devices such as resistors, capacitors and coil with conductive yarn, an off-the-shelf material. The knitting instructions for the sweater are available online, it can provide a free of cost, independent communications infrastructure. The concept was inspired by the protests on Taksim Square, Istanbul, Turkey, and associated violations of freedom of speech. A Piece of the Pie Chart: Feminist Robotics by Annina Rüst illuminates gender inequity in form of a production line, which decorates edible pies with pie charts, depicting gender ratios in tech affiliated corporate or public organisations.

Women are generally underrepresented in tech related workplaces and users of the gallery installation can browse and choose between various data sets on gender in technology, e.g. computer science graduation rates, before an ensemble of household applications and semi-pro robotics sorts the cake. The mere visualisation of data was not radical enough, so the finished pie can be shipped to the institution of which data (and gender inequity) originates, and where it can be consumed accordingly. Women have to be content with the smaller piece of the cake, also symbolic for economic inequality and the missed out experience of working in tech. Rüst was not satisfied with the claim that women are just not interested in tech, and further qualitative research in feminist technology showed that women are rather put off by its hostile macho culture and that technological pedagogy simply failed to inspire girls.

Tweeted image of a finished pie. Source: https://twitter.com/PieChartRobot

The PROTEST issue lives up to its title and emphasizes on projects, which propose hands-on political action and intervention with society, not in terms of providing solutions but to spark much needed discussion and inspire disruptive technology. Disobedient Electronics follows the publishing project Critical Making, which comprised 11 issues, so there is hopefully some more to come.

DOWNLOAD PRESS RELEASE (.pdf)

SEE IMAGES FROM ACCOMPANYING EVENTS

LISTEN to a recording of the conversation with John Conomos and Steven Ball at Furtherfield Gallery

Deep Water Web is a free exhibition at Furtherfield Gallery in London’s Finsbury Park, connecting opposite sides of the Earth to understand human impacts on the environment and the wider consequences for people living in both locations.

Artists Steven Ball (London, UK) and John Conomos (Sydney, Australia) have collaborated to present a multi-projection installation where London and Sydney are continuously connected across time zones. The exhibition is an immersive experience which the artists have termed a ‘hyperlandscape’ including real time streaming waterscapes and multiple local manifestations of global ecologies with their own sonic environments and narrated reflections.

Deep Water Web is a poetic meditation around contemporary and historical geopolitical contexts, underscored by London and Sydney’s situation around large bodies of tidal water in the forms of the River Thames and Sydney Harbour. These bodies of water bear material evidence of the local impact of global warming, such as rising tide levels caused by melting ice caps, leading to flooding, and increasingly extreme climate fluctuation. Both cities are also centres of neoliberal capitalism, inscribing the effects of privatisation, fiscal austerity and deregulation of markets across the planet.

Deep Water Web weaves rhetorical explication of postcolonial relationship, elaborating the precarious material forms of climate change, and post-labour late capitalist neoliberal urban developments of waterfronts of former Docklands, considered within the geological and rhetorical ecology of the Anthropocene.

The age of global warming and global neoliberal capitalism are figured here as critical rhetorical realms. These phenomena can be described as what Timothy Morton has called hyperobjects, objects so massively distributed in time and space as to transcend localisation. While they are impossible to comprehend at scale, hyperobjects exert a profound effect at a local level.

Deep Water Web will also become a catalyst for a workshops series at Furtherfield Commons, which will extend its themes through media based excavations. [dates and full details to be confirmed]

Both artists both have long standing moving image based practices and an interest in landscape and the representation of place. As a hyperlandscape this project suggests that questions of relationship to place, and the construction of landscape, can in the Anthropocene no longer be considered as simply pictorial representation or subjective experience, but is constituted from a range of critical, ethical, ecological, and political positions and concerns.

+ MORE INFO: http://deepwaterweb.net

Deep Water Web is supported by Arts Council England.

Exhibition Tour with artist Steven Ball

Tuesday 4 October 2016 – 5:30-6:15pm – Furtherfield Gallery

Revolutions and Complex Systems

Every Tuesday for 6 weeks

6:30 – 8:30pm at Furtherfield Commons – from 27 September 2016

BOOKING ESSENTIAL

A conversation with John Conomos and Steven Ball

2-3pm Saturday 29 October – Furtherfield Gallery

Booking is essential for this free event

Furtherfield in partnership with the antiuniversity and Radical Think Tank are proud to present this new 6-part course led by Graham Jones.

Aimed at people with an interest in social change, the course will apply concepts from complex systems theory to understanding revolutions and social movements. Sessions will involves a mix of speaker presentation and participatory discussions/activities, covering subjects such as ecology, network theory and new materialist philosophy.

Graham Jones is an activist based in East London, working with groups such as Radical Assembly, Radical Housing Network and Radical Think Tank. Booking Essential.

Steven Ball is an artist, writer and academic based in London, working with audio-visual media engaged with landscape and spatial representation, in local and global, social, political and post-colonial spheres. Since 2003 he has been Research Fellow at Central Saint Martins and was instrumental in developing the British Artists’ Film and Video Study Collection.

John Conomos is an artist, critic and writer based in Sydney, Australia. His books, essays and artworks are framed within four traditions of contemporary art: Anglo-American and Australian cultural studies, critical theory and post-structuralism. He is a New Media Fellow of the Australia Council for the Arts, and Honorary Professor at Victorian College of the Arts, University of Melbourne.

Furtherfield was founded in 1997 by artists Marc Garrett and Ruth Catlow. Since then Furtherfield has created online and physical spaces and places for people to come together to address critical questions of art and technology on their own terms.

Furtherfield Gallery

McKenzie Pavilion

Finsbury Park, London, N4 2NQ

Visiting Information

Furtherfield Gallery is supported by Haringey Council and Arts Council England

J. R. Carpenter reviews A Geology of Media, the third, final part of the media ecology-trilogy. It started with Digital Contagions: A Media Archaeology of Computer Viruses (2007) and continued with Insect Media (2010). It focuses beyond machines and technologies onto the chemistry and geological materials of media, from metals to dust.

Humans are a doubly young species — we haven’t been around for long, and we don’t live for long either. We retain a fleeting, animal sense of time. We think in terms of generations – a few before us, a few after. Beyond that… we can postulate, we can speculate, we can carbon date, but our intellectual understanding of the great age of the earth remains at odds with our sensory perception of the passage of days, seasons, and lifetimes.

The phrase ‘deep time’ was popularised by the American author John McPhee in the early 1980s. McPhee posits that we as a species may not yet have had time to evolve a conception of the abyssal eons before us: “Primordial inhibition may stand in the way. On the geologic time scale, a human lifetime is reduced to a brevity that is too inhibiting to think about. The mind blocks the information”1. Enter the creationists and climate change deniers, stage right. On 28 May 2015 the Washington Post reported that a self-professed creationist from Calgary found a 60,000-million-year-old fossil, which did nothing to dissuade him of his religious beliefs: “There’s no dates stamped on these things,” he told the local paper.2

In the late 15th-century, Leonardo Da Vinci observed fossils of shells and bones of fish embedded high in the Alps and privately mused in his notebooks that the theologians may have got their maths wrong. The notion that the earth was not mere thousands but rather many millions of years old was first put forward publicly by the Scottish physician turned natural scientist James Hutton in Theory of the Earth, a presentation made to the Royal Society of Edinburgh in 1785 and published ten years later in two massive volumes3. It is critical to note that among Hutton’s closest confidants during the formulation of this work were Joseph Black, the chemist widely regarded as the discoverer of carbon dioxide, and the engineer James Watt, whose improvements to the steam engine hastened the Industrial Revolution in Great Britain. Geology emerged as a discipline on the eve of a period of such massive social, scientific, economic, political, and environmental change that it precipitated what many modern geologists, ecologists, and prominent media theorists are now categorising as a new geological epoch, the Anthropocene. As Nathan Jones recently wrote for Furtherfield: “The Anthropocene… refers to a catastrophic situation resulting from the actions of a patriarchal Western society, and the effects of masculine dominance and aggression on a global scale.”4

In his latest book, A Geology of Media (2015)5, Finnish media theorist Jussi Parikka turns to geology as a heuristic and highly interdisciplinary mode of thinking and doing through which to address the complex continuum between biology and technology presented by the Anthropocene. Or the Anthrobscene, as Parikka blithely quips. In putting forward geology as a methodology, a conceptual trajectory, a creative intervention, and an interrogation of the non-human, Parikka argues for a more literal understanding of ‘deep time’ in geological, mineralogical, chemical, and ecological terms. Whilst acknowledging the usefulness of the concepts of anarachaeology and varientology put forward by Siefried Zielinski in Deep Time of the Media (2008)6, Parikka calls for an even deeper time of the media — deeper in time and in deeper into the earth.

In Theory of the Earth, Hutton referred to the earth as a machine. He argued: “To acquire a general or comprehensive view of this mechanism of the globe… it is necessary to distinguish three different bodies which compose the whole. These are, a solid body of earth, an aqueous body of sea, and an elastic fluid of air.”13 Of the machine-focused German media theorists, Parikka demands – what is being left out? “What other modes of materiality deserve our attention?”7 Parikka proposes the term ‘medianatures’ — a variation on Donna Haraway’s ‘naturecultures’8 — as a term through which to address the entangled spheres and sets of practices which constitute both media and nature. Further, Parikka reintroduces aspects of Marxist materialism to Friedrich Kittler’s media materialist agenda, relentlessly re-framing the production, consumption, and disposal of hardware in environmental, political, and economic contexts, and raising critical social questions of energy consumption, labour exploitation, pollution, illness, and waste.

Drawing upon Deleuze and Guattari’s formulation of a ‘geology of morals’9, Parikka writes: “Media history conflates with earth history; the geological materials of metals and chemicals get deterritorialized from their strata and reterritorialized in machines that define our technical media culture”10. Within this geologically inflected materialism, a history of media is also a history of the social and environmental impact of the mining, selling, and consuming of coal, oil, copper, and aluminium. A history of media is also a history of research, design, fabrication, and the discovery of chemical processes and properties such as the use of gutta-percha latex for use the insulation of transatlantic submarine cables, and the extraction of silicon for use in semiconductor devices. A history of the telephone is entwined with that of the copper mine. How can we possibly think of the iPhone as more sophisticated than the land line when we that know that beneath its sleek surface – polished by aluminium dust – the iPhone runs on rare earth minerals extracted by human bodies labouring in deplorable conditions in open-pit mines?

Jussi Parikka is a professor in technological culture and aesthetics and Winchester School of Art. Although his his definition of media remains rooted in the disciplinary discourses of media studies, media theory, media history, and media art, he advocates for and indeed actively engages in an interdisciplinary approach to media theory. He cites a number of excellent examples from contemporary media art, not as illustrations of his arguments but rather as guides to his thinking. He also draws upon a wide range of other references from visual art, science, literature, psychogeography, philosophy, and politics. This overtly interdisciplinary approach to media theory provides a number of intriguing openings for readers, scholars, and practitioners in adjacent fields to consider. For example, Parikka’s evocation of Robert Smithson’s formulation of ‘abstract geology’11 in relation to land art invites further explication of the connection between land art, sculpture, and the geology of sculptural media. For thousands of years sculptors have practised a geology of media, making and shaping clay, quarrying and carving stone, and smelting, melting, and casting metal. Further, Parikka’s discussion of the pictorial content of a number of paintings in the context of this book invites the consideration of the geology of paint as a medium, entwined with the elemental materiality of cadmium, titanium, cobalt, ochre, turpentine, graphite, and lead.

Media is a concept in crisis. As it travels across scientific, artistic, and humanistic disciplines it confuses and confounds boundaries between what media is and what media does in a wide range of contexts. This confusion signposts the need for new vocabularies. If geology has taught us anything, it’s that this too will take time. In endeavouring to explain how it happens that flames sometimes shoot out through the throat of Mount Etna, the Epicurian poet Lucretius (c. 100 – c. 55 BC) wrote: “You must remember that the universe is fathomless… If you look squarely at this fact and keep it clearly before your eyes, many things will cease to strike you as miraculous.”12 So too, Parikka prods us to think big, to get past our primordial inhibitions, to look beyond mass media consumerism to what I shall call a ‘massive media’ – a conception of media operating on a global and geological scale. A Geology of Media is a green book, overtly ecological. In his call for a further materialisation of media theory through a consideration of the media of earth, sea, and air Parikka has put forward an assemblage of material practices indispensable to any discussion of the mediatic relations of the Anthropocene.

“…the futility in this case is underscored by the silly project of bringing forth by mechanical means what nature in any case provides in abundance”1

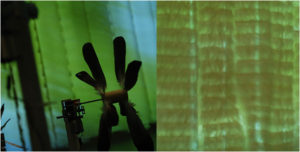

Visitors to Annette Barbier’s Casualties at Chicago Artists Coalition are confronted by an abundance of dead birds—splayed photographs of birds that nature did not provide any instinct for dealing with gigantic, human-made structures of glass and concrete. Inside these structures are people who have no time to question whether they have any instinct for the same. Barbier’s installation is the intersection of these two sets of animals. Past the short foyer of dead birds, visitors are stopped by a large curtain of feathers without apparent opening. The curtain is lit from behind, flickering. It would be easy to stop here, assuming this giant barrier is the end of the exhibit. In order to progress into the installation, visitors must violate the haptic taboo of the gallery, split the curtain and move forward. Beyond the curtain, the small gallery space is spare. The focus of the installation is an arrangement of kinetic sculptures, sitting on a felt blanket on the ground. Each piece is a rotating wheel of bird feathers, held up by a piece of small gauge PVC pipe. Wires run down the pipe into a single control card. The materials are all apparent but the effect transforms them into minimal bird analogs. With three people in the room, it is easy to see that the feathers rotate faster when approached. With a crowd in the space, the effect is more chaotic and it becomes impossible to discern any relationship between proximity and movement.

Interactivity inevitably removes focus from anything but the interaction, if it is noticed at all. We saw multiple people investigate the piece, focused only on the electronics, trying to figure out how to “make it go.” In Barbier’s use, this is perhaps an intentional distraction, underscoring the disturbing relationship between humans and undomesticated animals in urban environments. The bird analogs spin pointlessly, pathetically, in relation to our nearness and stand in place of a connection to the natural world. With little time for contemplation and a schedule full of assessment, budget cuts, reorganization and perpetual training, the students, staff and faculty of the University of Illinois (where the majority of Barbier’s photos were taken) only encounter birds as they rain down from their impact against the Brutalist architecture.

The “silly project” described in the Danto quote at the beginning of this review describes Paul Klee’s painting Twittering Machine. Mechanical birds perch above a void, feet wrapped permanently around the wire that controls them. They are joyful and terrifying, tongues of exclamation marks and sharp barbs. One wears a spring while another resembles a fly fishing lure. They are unstable, with questionable guy-wires holding them upright. Their perch is a wave on which they will bobble up and down, and perhaps fall, but only if the handle is turned. Barbier’s birds, like Klee’s machine, are a mere mechanical replacements for living beings, precariously perched and only moving within a severely confined environment.

“In my writing I got so interested in fakes that I finally came up with the concept of fake fakes. For example, in Disneyland there are fake birds worked by electric motors which emit caws and shrieks as you pass by them. Suppose some night all of us sneaked into the park with real birds and substituted them for the artificial ones. Imagine the horror the Disneyland officials would feel when they discovered the cruel hoax. Real birds!”2

Where Danto saw an abundance of nature, Philip K. Dick, quoted above, sees the replacement of wildlife with structured wildlife encounters. The artificial birds flutter and respond to our presence but only represent birds as humans imagine them. Barbier’s fake, electric pinwheel birds reduce the illusion to a mockery. The foyer of the installation shows the results of human architecture, inside we are confronted with the futility of seeking a technological solution.

“We are the first generations born into a new and unprecedented age — the age of ecocide. To name it thus is not to presume the outcome, but simply to describe a process which is underway. The ground, the sea, the air, the elemental backdrops to our existence — all these our economics has taken for granted, to be used as a bottomless tip, endlessly able to dilute and disperse the tailings of our extraction, production, consumption.”3

Casualties is not a call to action but a dirge, room silent but for the mechanical sound of small motors. Unfortunately, the human-centered reduction that Barbier’s sculptures outline, a false dichotomy in which we can only “save” or “destroy” nature, is undermined by an associated event. In a catalog insert, we are invited to a workshop on Preventing Bird Strikes. In this two hour workshop, we can learn to “create [our] own DIY devices to help birds avoid collisions with reflective glass surfaces.” The disjunction of human and natural is a much deeper issue and Barbier’s installation poetically makes visible a small intersection in civilization that is incredibly complex, and broken.

_

Images and video courtesy of Annette Barbier

For over 17 years, Furtherfield has been working in practices that bridge arts, technology, and social change. Over these years, we have been involved in many great projects and collaborated with and supported various talented people. Our artistic endeavours include net art, media art, hacking, art activism, hacktivism and co-curating. We have always believed it is essential that the individuals at the heart of Furtherfield practice in arts and technology and are engaged in critical enquiry. For us, art is not just about running a gallery or critiquing art for art’s sake. The meaning of art is in perpetual flux, and we examine its changing relationship with the human condition. Furtherfield’s role and direction as an arts collective is shaped by the affinities we identify among diverse independent thinkers, individuals and groups who have questions to ask in their work about the culture.

Here I present a selection of Furtherfield projects and exhibitions featured in the public gallery space we have run in Finsbury Park in North London for the last two years. I set out some landmarks on the journey we have experienced with others and end my presentation with news of another recently opened space (also in the park) called the Furtherfield Commons.

Running themes in this presentation include how Furtherfield has lived through and actively challenged the disruptions of neoliberalism. The original title for this presentation was ‘Artistic Survival in the 21st Century in the Age of Neoliberalism’. The intention was to stress the importance of active and open discussion about the contemporary context with others. The spectre of neoliberalism has paralleled Furtherfield’s existence, affecting the social conditions, ideas and intentions that shape the context of our work: collaborators, community and audience. Its effects act directly upon ourselves as individuals and around us: economically, culturally, politically, locally, nationally and globally. Neoliberalism’s panoptic encroachment on everyday life has informed Furtherfield’s motives and strategies.

In contrast with most galleries and institutions that engage with art, we have stayed alert to its influence as part of a shared dialogue. The patriarch, neoliberalism, de-regulated market systems, corporate corruption and bad government; each implement the circumstances where we, everyday people, are only useful as material to be colonized. This makes us all indigenous peoples struggle under the might of the wealthy few. Hacking around and through this impasse is essential if we maintain human integrity and control over our social contexts and ultimately survive as a species.

“The insights of American anarchist ecologist Murray Bookchin into environmental crisis hinge on a social conception of ecology that problematises the role of domination in culture. His ideas become increasingly relevant to those working with digital technologies in the post-industrial information age, as big business develops new tools and techniques to exploit our sociality across high-speed networks (digital and physical). According to Bookchin, our fragile ecological state is bound up with a social pathology. Hierarchical systems and class relationships so thoroughly permeate contemporary human society that the idea of dominating the environment (to extract natural resources or to minimise disruption to our daily schedules of work and leisure) seems perfectly natural despite the catastrophic consequences for future life on earth (Bookchin 1991). Strategies for economic, technical and social innovation that focus on establishing ever more efficient and productive systems of control and growth, deployed by fewer, more centralised agents, have been shown to be both unjust and environmentally unsustainable (Jackson 2009). Humanity needs new social and material renewal strategies to develop more diverse and lively ecologies of ideas, occupations and values.” [1] (Catlow 2012)

It is no longer critical, innovative, experimental, avant-garde, visionary, evolutionary, or imaginative to ignore these large issues of the day. Suppose we, as an arts organization, shy away from what other people are experiencing in their daily lives and do not examine, represent and respect their stories. In that case, we rightly should be considered part of an irrelevant elite and seen as saying nothing to most people. Thankfully, many artists and thinkers take on these human themes in their work in various ways, on the Internet and in physical spaces. So much so, this has introduced a dilemma for the mainstream art world regarding its relevance and whether it is contemporary.

Furtherfield has experienced, in recent years, a large-scale shift of direction in art across the board. And this shift has been ignored (until recently) by mainstream art culture within its official frameworks. However, we need not only to thank the artists, critical thinkers, hackers and independent groups like ours for making these cultural changes, although all have played a big role. It is also due to an audience hungry for art that reflects and incorporates their social contexts, questions, dialogues, thoughts and experiences. This presentation provides evidence of this change in art culture, and its insights flow from the fact that we have been part of its materialization. This is grounded knowledge based on real experience. Whether it is a singular movement or multifarious is not necessarily important. But, what is important is that these artistic and cultural shifts are bigger than mainstream art culture’s controlling power systems. This is only the beginning, and it will not go away. It is an extraordinary swing of consciousness in art practice forging other ways of seeing, being, thinking, making and becoming.

Furtherfield is proud to have stuck with this experimental and visionary culture of diversity and multiplicity. We have learned much by tuning into this wild, independent and continuously transformative world. On top of this, new tendencies are coming to the fore, such as re-evaluations and ideas examining a critical subjectivity that echo what Donna Haraway proposed as ‘Situated Knowledge’ and what the Vienna-based art’s collective Monochrom call ‘Context Hacking’. Like the DADA and the Situationist artists did in their time, many artists today are re-examining current states of agency beyond the usually well-promoted, proprietorial art brands, controlling hegemonies and dominating mainstream art systems.

Most Art Says Nothing To Most People.

“The more our physical and online experiences and spaces are occupied by the state and corporations rather than people’s own rooted needs, the more we become tied up in situations that reflect officially prescribed contexts, and not our own.” [2]

To start things off, I want to refer to a past work that Heath Bunting (co-founder of irational.org) and I were involved with in 1991. The above image is a large paste-up displayed on billboards around Bristol in the UK. At the time, as well as being part of other street art projects, pirate radio and BBS boards, Heath and I and others were members of the art activist collective Advertising Art. The street art we made critiqued presumed ownership of art culture by the dominating elites. The words “Most Art Says Nothing To Most People” have remained an inner mantra ever since.

Furtherfield is inspired by ideas that reach for a grassroots form of enlightenment and nurture progressive ideas and practices of social and cultural emancipation. The Oxford English Dictionary describes Emancipation as “the fact or process of being set free from legal, social, or political restrictions; liberation: the social and political emancipation of women and the freeing of someone from slavery.”

“Kant thought that Enlightenment only becomes possible when we are able to reason and to communicate outside of the confines of private institutions, including the state.” [3] (Hind 2010)

Well, a start would be getting organised and building something valuable with others.

As usual, it is up to those people who know that something is not working and those feeling the brunt of the issues affecting them who end up trying to change the conditions. It is unlikely that this pattern of behaviour will change.

To expect or even wish those who rule and those serving them to change, challenge their behaviours and seriously critique their actions is as likely as winning the National Lottery, perhaps even less.

Art critic Julian Stallabrass proposes that there needs to be an analysis of the operation of the art world and its relation to neoliberalism. [4]

In the above publication, Gregory Sholette argues “that imagination and creativity in the art world thrives in the non-commercial sector, shut off from prestigious galleries and champagne receptions. This broader creative culture feeds the mainstream with new forms and styles that can be commodified and utilized to sustain the few elite artists admitted into the elite. […] Art is big business: a few artists command huge sums of money, and the vast majority are ignored, yet these marginalized artists remain essential to the mainstream cultural economy serving as its missing creative mass. At the same time, a rising sense of oppositional agency is developing within these invisible folds of cultural productivity. Selectively surveying structures of visibility and invisibility, resentment and resistance […] when the excluded are made visible when they demand visibility, it is always ultimately a matter of politics and rethinking history.” [5] (Sholette 2013)

Drawing upon Sholette’s inspirational, unambiguous and comprehensive critique of mainstream art culture in the US. I want to consider examples closer to home blocking artistic and social emancipation avenues that also need an urgent critique. And this blockage resides within media art culture (or whatever we call it now) itself. Recently, I read a paper about ‘Post-Media’ – said to “unleash new forms of collective expression and experience” [6]- which featured in its text-only established names. Furtherfield is native to ‘Post-Media’ processes, a concept that theorists in media art culture are just beginning to grasp. This is because they tend to rely on particular theoretical canons and the defaults of institutional hierarchies to validate their concepts. Also, most of the work they include in their research is shown in established institutions and conferences. They assume that because a particular artwork or practice is accepted within the curatorial remits of a conference theme, the art shown represents what is happening, thus more valid than other works and groups not included. This is a big mistake. It only reinforces the conditions of a systemic, institutionalised, privileged elite and enforces a hierarchy that will reinforce the same myopic syndromes of mainstream art culture. The extra irony here is that many supposedly insightful art historians and theorists advocate a decentralised, networked culture in their writings or as a relational context. However, many do not support or create alternative structures with others. The real problem is how they acquire their knowledge. Presently the insular and hermetically sealed dialectical restraints and continual reliance on central hubs as official reference is distancing them from the actual culture they propose to be part of.

“We must allow all human creativity to be as free as free software” [7] (Steiner, 2008)

Furtherfield comes from a cultural hacking background and has incorporated into its practice ideas of hacking not only with technology but also in everyday life. Furtherfield is one big social hack. Hack Value advocates an art practice and cultural agency where the art includes the mechanics of society as part of its medium and social contexts with deeper resonances and a critical look at the (art) systems in place. It disrupts and discovers fresh ways of looking and thinking about art, life and being. Reclaiming artistic and human contexts beyond the conditions controlled by elites.

Hack Value can be a playful disruption. It is also maintenance for the imagination, a call for a sense of wonder beyond the tedium of living in a consumer, dominated culture. It examines crossovers between different fields and practices concerning their achievements and approaches in hacking rather than as specific genres. Some are political, and some are participatory. This includes works that use digital networks, physical environments, and printed matter. What binds these examples together is not only the adventures they initiate when experimenting with other ways of seeing, being and thinking. They also share common intentions to loosen the restrictions, distractions and interactions dominating the cultural interfaces, facades and structures in our everyday surroundings. This relates to our relationship with food, tourism, museums, galleries, our dealings with technology, belief systems and community ethics.

Donna Haraway proposes a kind of critical subjectivity in the form of Situated Knowledges.

“We seek not the knowledges ruled by phallogocentrism (nostalgia for the presence of the one true world) and disembodied vision. We seek those ruled by partial sight and limited voice – not partiality for its own sake but, rather, for the sake of the connections and the unexpected openings situated knowledges make possible. Situated knowledges are about communities, not isolated individuals.” [8] (Haraway 1996)

Furtherfield had run [HTTP], London’s first public gallery for networked media art, since 2004 from an industrial warehouse in Haringey. In 2012 the gallery moved to a public location at the McKenzie Pavilion in the heart of Finsbury Park, North London.

However, we are not just a gallery; we are a network connecting beyond a central hub.

“It is our contention that by engaging with these kinds of projects, the artists, viewers and participants involved become less efficient users and consumers of given informational and material domains as they turn their efforts to new playful forms of exchange. These projects make real decentralised, growth-resistant infrastructures in which alternative worlds start to be articulated and produced as participants share and exchange new knowledge and subjective experiences provoked by the work.” [9] (Garrett & Catlow, 2013)

The park setting informs our approach to curating exhibitions in a place with a strong local identity, a public green space set aside from the urban environment for leisure and enjoyment by a highly multicultural population.

We are simultaneously connected to a network of international critical artists, technologists, thinkers and activists through our online platforms, communities, and wider networked art culture. We get all kinds of visitors from all backgrounds, including those who do not normally visit art spaces. We are not interested in pushing the mythology of high art above other equally significant art practices. Being accessible has nothing to do with dumbing down. It concerns making an effort to examine deeper connections between people and the social themes affecting theirs and our lives. We don’t avoid big issues and controversies and constantly engage in a parallel dialogue between these online communities and those meeting us in the park.

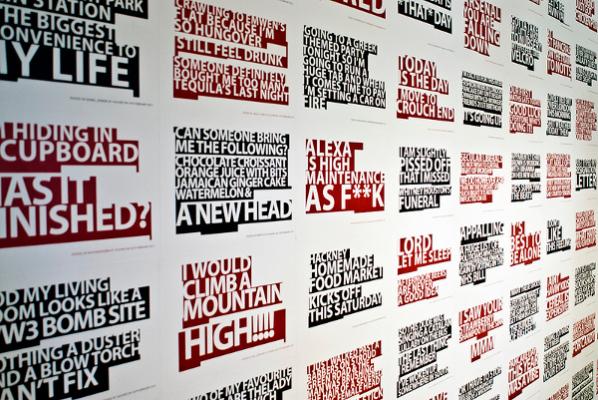

We feature works incorporating local people’s contributions, bringing them closer to the art and engagement of social dialogue. For instance, London Wall, N4 by Thomson and Craighead, reflected a collective stream of consciousness of people all around Finsbury Park, gathering their Tweets to print out and paste onto the gallery walls. By retweeting the images of the tweet posters, we gathered many of the original authors in the gallery to see their words physically located among others made in the vicinity.

Crow_Sourcing by Andy Deck invited people to tweet animal expressions from around the world – illuminating the link between the formation of human language and our relationships with other wild webs of animal life. Gallery visitors illustrated their animal idioms, drawing directly onto the gallery walls, inspired by the ducks, crows, squirrels and dogs that inhabit the park.

We feature works dealing with networked and pervasive technologies’ human and social effects. Web 2.0 Suicide Machine by moddr_ proposed an improvement to our ‘real’ lives by providing a one-click service to remove yourself, your data, and your profile information forever from Facebook, Twitter and MySpace, replacing your icon (again, forever) with a logo depicting a noose. They also reflect on new forms of exposure and vulnerabilities they give rise to, such as Kay’s Blog, by Liz Sterry, which replicated in physical space the unkempt bedroom of an 18-year-old Canadian girl based only on her blog posts, to eerie effect. The intention is to reach people in a way that has people question their relationship with those technologies. This does not mean promoting technology as a solution to art culture but exploiting it to connect with others and critique technologies simultaneously.

Below: Selection of images from original slide presentation – exhibitions & events.

On the 23rd of November, we opened our second space in the park, ‘The Furtherfield Commons’. It kicked off with The Dynamic Site: Finsbury Park Futures, an exhibition by students from the Writtle School of Design (WSD) featuring ideas and visions for future life in Finsbury Park, coinciding with the launch.

This new lab space for experimental arts, technology and community explores ways to establish commons in the 21st Century. It draws upon influences from the 1700s when everyday people in England, such as Gerrard Winstanley and collaborators, forged a movement known as the Diggers, the True Levellers, to reclaim and claim common land from the gentry for grassroots, peer community interests. Through various workshops, residencies, events & talks, we will explore what this might mean to people locally and in connection with our international networks. These include free software works, critical approaches to gardening, gaming and other hands-on practices where people can claim direct influence in their everyday environments in the physical world, to initiate new skills and social change on their terms. From what we have learned from our years working with digital networks, we intend to apply tactical skills and practices into everyday life.

Furtherfield is a network across different time zones, platforms & places – online & physical, existing as various decentralised entities. A culture where people interact: to create, discuss, critique, review, share information, collaborate, build new artworks & alternative environments (technological, ecological, social or both), examine & try out value systems. “A rhizome has no beginning or end; it is always in the middle, between things, interbeing, intermezzo.” (Brian Massumi 1987)

DADA, Situationism, punk, Occupy, hacktivism, networks, Peer 2 Peer Culture, feminism, D.I.Y, DIWO, Free Software Movement, independent music labels, independent thinkers, people we work with, artists, activism, grassroots culture, community…

This comprises technological and physical forms of hacking. It also includes aspects and actions of agency-generation, skill, craft, disruption, self-education, social change, activism, aesthetics, re-contextualizing, claiming or reclaiming territories, independence, emancipation, relearning, rediscovering, play, joy, being imaginative, criticalness, challenging borders, breaking into and opening up closed systems, changing a context or situation, highlighting an issue, finding ways around problems, changing defaults, and restructuring things – Claiming social contexts & artistic legacies with others!

This text is a re-edited slide presentation first shown at the ICA, London, UK, on 16th November 2013 (Duration 25 min). Intermediality: Exploring Relationships in Art. Speakers Katrina Sluis, Peter Ride, Sean Cubitt & Marc Garrett.

http://www.ica.org.uk/39077/Talks/Intermediality-Exploring-Relationships-in-Art.html

Transdisciplinary Community (TDC) Leicester UK 27th Nov 2013 (45 min). Institute of Creative Technologies. De Montfort University.

Two projects Gregory Sholette is currently involved in:

It’s the Political Economy, Stupid. Curated by Oliver Ressler & Gregory Sholette

http://gallery400.uic.edu/exhibitions/its-the-political-economy-stupid

Matt Greco & Greg Sholette | Saadiyat Island Workers Quarters Collectable, 2013

http://bit.ly/1eSI5kX

—————————————————–

All exhibitions, events & projects at Furtherfield – http://www.furtherfield.org/programmes/exhibitions

Contact: info@furtherfield.org

Visiting Information

Imagine visiting Finsbury Park in the not too distant future…

You could explore the sensory and medicinal properties of different plants in the Discovery Meadows; Play Glades offering people of all ages a range of adventurous physical challenges within a variety of wooded areas; visitors could go on a cultural tour of ‘natural rooms’ in the park, accessed through mobile devices; community gardens used for a wide range of events supporting and encouraging local people to come together around pleasurable growing, foraging and cooking events; Memorial Gardens providing an inspiring and elegant space for people of all faiths to take a moment to remember their passed loved ones.

These are just some of the futuristic ideas that students from the Writtle School of Design (WSD) will be exhibiting at Furtherfield that imagine possible futures for Finsbury Park.

In early 2013 WSD students created plans for the whole park, and then a number of individual designs for key spaces within the Park. They were asked to look at ways that Finsbury Park and Furtherfield could both provide more pleasing spaces and encounters for the surrounding communities. The opening of Furtherfield Commons, a new pop-up art, technology, and community space located within the park at the Finsbury Park Station entrance, will also be celebrated. Furtherfield Commons will serve as the venue for presentations from Furtherfield and Writtle School of Design students and staff about their visions for the park alongside an exhibition of the full array of inspirational images and ideas, and video interviews with the designers. Visitors are invited to make comments.

Press view and VIP private view: Friday 22 November, 2-5pm

Open 12-4pm Saturday and Sunday for two weekends. 23, 24, 30 November and 1 December 2013

Local people are encouraged to come along and respond to the designs.

Furtherfield Commons

Finsbury Park

Near Finsbury Gate On Seven Sisters Road

E: info@furtherfield.org

Furtherfield Gallery is supported by Haringey Council and Arts Council England.

I met Eugenio Tisselli in Edinburgh at the Remediating the Social conference in November 2012. Eugenio gave a presentation on the project Sauti ya wakulima, “The voice of the farmers”: A collaborative knowledge base created by farmers from the Chambezi region of the Bagamoyo District in Tanzania, and “by gathering audiovisual evidence of their practices they use smartphones to publish images and voice recordings on the Internet”, documenting and sharing their daily practices.

I was struck by his sensitivity to the social contexts and political questions around this type of project engagement. This interview explores the challenges we all face in connecting to a deeper understanding of what technology can succeed in doing beyond the usual hype of the ‘New’ and its entwined consumerist diversions. Not only does the conversation highlight how communities can work together in collaborating with technology on their own terms. But, it also discusses the artists’ role in the age of climate change and the economic crisis, locally and globally.

Marc Garrett: Can you explain how and why the Sauti ya wakulima, “The voice of the farmers” project came about?

Eugenio Tisselli: Sauti ya wakulima is the fruit of my collaboration in the megafone project, started in 2004 by Catalan artist Antoni Abad. During six years, we worked with different groups at risk of social exclusion, such as disabled people, immigrants or refugees. The idea was to provide these groups with the tools to make their voices heard: smartphones with a special application that made it easy to capture images, sound recordings or short videos, and a web page where these contents could be directly uploaded. Using these tools, the participants of each project were able to create a collaborative, online “community memory”, in which they could include whatever they considered to be relevant. Although megafone was relatively successful and, in some cases, made a positive impact on the people who participated, I was worried that the project was becoming too dispersive. We worked in six countries, with extremely different groups. So, in 2011, I decided to follow my own path and apply a similar methodology into more focused projects, related with sustainable agriculture and environmental issues. I realized that the projects which sought to increase the empowerment of a community could become too complex for a single artist to handle. That’s why, in Sauti ya wakulima, I’m not “the artist”, but a member of a transdisciplinary team which includes biologists, agricultural scientists and technicians. Such a team came together after my PhD advisor Angelika Hilbeck, my colleague Juanita Sclaepfer-Miller and myself came across the possibility of working with farmers in Tanzania. The network formed by local researchers, farmers and ourselves was quickly formed, so we started the project on March, 2011.

MG: I find it interesting that you made the decision to put the role of artist aside. This reminds me of a discussion in Suzi Gablik’s book published in 1995 ‘Conversations before the end of time’; where James Hillman in an interview talks about learning to refocus our attention from ourselves and onto the world. Further into the conversation Gablik says “In our culture, the notion of art being a service to anything is an anathema. Service has been totally deleted from our view point. Aesthetics doesn’t serve anything but itself and its own ends”.[2]

So, I have two questions here. The first is how important was it for you to put aside your status as an ‘artist’, and what difference did it make?

And, where do you think you and others may fit when considering the discussion between Gablik and Hillman?

ET: It is important for me to make it clear that I didn’t abandon my role as an artist. Instead, I fully assumed my status, but only as a member of a transdisciplinary team. I believe that this may be a point of departure from the classical view of the artist as a “lone genius”, which is closely related to the discussion about service in art. So I’ll try to interweave both questions together. In a recent publication, Pablo Helguera aimed to set a curriculum for socially engaged art. He identified the new set of skills to be acquired by the artists, and the issues they must address when dealing with social interaction. But, as Helguera suggests, perhaps what’s most important is to overcome the “prevailing cult of the individual artist”, which becomes problematic for those whose goal is “to work with others, generally in collaborative projects with democratic ideals.” [3] To me, this implies that the artist must give up control of the work to a certain degree. I find myself in this scenario, and I think of my role in Sauti ya wakulima as that of an instigator and coordinator. Furthermore, all of us involved in Sauti ya wakulima aim to effect actual changes in the lives of the participating farmers, rather than obtaining purely symbolic results. Our project is a socially engaged artwork that wants to be useful, to deliver a service.

We are living in urgent times, beyond any doubt. Looming global challenges, such as climate change, radically cancel the luxury of being useless, of not doing anything. This includes the artist who, as any other citizen, is called to use his or her abilities to help in preventing a catastrophe. I especially like Franco “Bifo” Berardi’s proposal about the new task that the artist might assume: that of reconstructing the conditions for social solidarity. This work of reconstruction would oppose competition, a value often found in the markets that deal with self-referential, self-serving artworks. Solidarity, writes Berardi, is neither an ethical nor a political program, but a pure aesthetic pleasure [4]. In my opinion, the artists who still embrace the idea that art should only serve its own ends will become those who play the lyre while our world burns.

MG: What kind of behaviours began to emerge once the farmers took control of the smartphones supplied?

ET: It was quite interesting to see that the farmers started to use the phones for purposes which were different from those that we had originally proposed. This happened very soon after the project started. Only one month had passed, and the farmers had already started to go beyond merely documenting the effects of climate change. They interviewed other farmers, and asked them all sorts of questions about their crops and agricultural techniques, their opinions and views. In short, they slowly laid out a web of mutual learning. This was a real eye-opener for us. As we began to observe this, the environmental researchers in the team became worried that the farmers were deviating from the goals that we had set. I wanted to leave room for this deviation, as I was particularly interested in studying the process of technological appropriation. So I had to convince the researchers that we should leave enough room for the farmers to freely explore the potentials of the smartphones. It was not easy but, in the end, negotiating the tensions between a goal-oriented and an open-ended research turned out to be quite fruitful.

On one hand, the farmers found that they could shape the project to fit their interests which, as they said, were to “learn about what other farmers in remote areas were doing.” On the other, the researchers finally realized that the images and voice narrations posted by the farmers were an invaluable source of information about what was actually going on in the farms and within the communities. Sometimes, agricultural initiatives may be designed with an insufficient understanding of the social context in which they are applied. By allowing the farmers to publish a wide range of topics, Sauti ya wakulima became a “community memory” that reveals rich details about farming and the social life of rural communities in Bagamoyo.

MG: In your presentation at Remediating the Social, I remember a quote from one of the farmers saying “The project helped me learn that phones can be used for other things besides calling people, and that computers can also be used to solve problems: they are not just a fancy thing for the rich people in towns.” What’s interesting here is, these words could be said any where. And that our consumer orientated culture could still learn a few things regarding uses of technology.

What lessons can the farmers teach ‘us’ in a culture where computers are part of the everyday life?

ET: I have interpreted this particular quote in two different ways. The first, most obvious one, is that the farmers discovered that the smartphones and the web can be useful tools, which may be shaped and adapted to meet their needs. For many of them, Sauti ya wakulima was their first chance at trying out these technologies. And, happily, the project showed us all that they can become an important ingredient in making farmers’ lives a little better.

However, my second interpretation is not as optimistic: in the quote, there is an explicit comparison between the (poor) farmers living in remote areas and “the rich people in towns.” Moreover, the fact that smartphones are explicitly considered as fancy devices points towards issues which need to be handled very carefully. In every part of the world, technological gadgets are quickly becoming symbols of social status. Currently, I am working in a rural zone in southern Mexico where cellphone coverage was nonexistent only two years ago. But as soon as the first antennas were installed, young people in those communities started buying smartphones, and now there is an open competition to see who has the fanciest one. A similar thing happens in Bagamoyo.

So, of course, smartphones can be useful tools, but they can also bring more consumerism into poor communities. This is very dangerous. I’d like to stress that, in our project, the smartphones are used as shared tools. This means that there is a limited number of devices available, and everyone must have a chance to use them at least once. I believe that this is a small but significant contribution towards diluting the extreme individualism and consumerism that are closely linked to these technologies.

The farmers I have met in Bagamoyo have a very strong sense of community. Although their farms can be very far apart, sometimes with no roads between them, they still get together very often. They work together, learn together, have fun together. That’s the biggest lesson I’ve learned: we need each other’s presence. Quoting “Bifo” again, we are living in a time of precarization of the encounter of bodies in physical space. I agree with him that the most important poetic revolution has to be the re-activation of bodies. The farmers, with the great efforts they make to get together, and the great joy they find in doing so, have taught me a great deal: I need to get out of Facebook and step in to the “here and now”, together with others.

MG: What has this experience taught you. And how will it impact your future practice as an artist?

ET: I have partially replied to the first part of this question. But besides learning how to re-dimension the importance of computers in my life, I have also learnt a lot about agriculture. This is not a minor thing for me: after all these years of living in big cities, and realizing that I lack a basic connection to the earth, I believe I have found the best possible teachers. Of course, I’ve also learnt a lot about how to work with non-expert users of technology. This has made me better as a teacher. And, as you can imagine, many of the things we take for granted at home won’t necessarily work in Bagamoyo. So, doing projects in difficult environments has taught me to adapt, and to transform things that escape my control into opportunities. All of this changes me, not only as an artist but as a human being. My artistic practice is already quite different from what it was before Sauti ya wakulima. I have adopted a very critical position towards technology. Now, this is also a major shift: I started programming creatively when I was ten years old, and have been a media artist almost since then. But I feel I can’t go on with those artistic explorations, knowing what I know now. Consequently, last year I wrote and published a small note explaining why I stopped creating works of e-Literature, a field in which I was involved for more than ten years [5]. That was both a closure and a point of departure. Let’s see what the future brings.

Excerpt from ‘Why I have stopped creating e-Lit’ by Tisselli (November 25th, 2011)

Dear friends: this morning I went for a walk along the Naviglio Grande in Milan, and I entered a shop selling second-hand books. There I found a small book, “The Computer in Art”, by Jasia Reichardt, published in London in 1971. The book described the works of pioneers of Computer Art, such as Charles Csuri or Michael Noll, who were active at that time. A real gem. But the biggest surprise came when I turned to the last page, on which the previous owner had written: “I married on 23, November. I would like to be a man, not artist, not engineer, a man.”

I took the book with me.

Those involved in the Sauti ya wakulima / The voice of the farmers project.

The farmers: Abdallah Jumanne, Mwinyimvua Mohamedi, Fatuma Ngomero, Rehema Maganga, Haeshi Shabani, Renada Msaki, Hamisi Rajabu, Ali Isha Salum, Imani Mlooka, Sina

Rafael.

Group coordinator / extension officer: Mr. Hamza S. Suleyman

Scientific advisors: Dr. Angelika Hilbeck (ETHZ), Dr. Flora Ismail (UDSM)

Programming: Eugenio Tisselli, Lluís Gómez

Translation: Cecilia Leweri

Graphic design: Joana Moll, Eugenio Tisselli

Project by: Eugenio Tisselli, Angelika Hilbeck, Juanita Schläpfer-Miller

Sponsored by: The North-South Center, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology – Zürich

With the support of: The Department of Botany, University of Dar es Salaam (UDSM)

The insights of American anarchist ecologist Murray Bookchin, into environmental crisis, hinge on a social conception of ecology that problematises the role of domination in culture. His ideas become increasingly relevant to those working with digital technologies in the post-industrial information age, as big business daily develops new tools and techniques to exploit our sociality across high-speed networks (digital and physical). According to Bookchin our fragile ecological state is bound up with a social pathology. Hierarchical systems and class relationships so thoroughly permeate contemporary human society that the idea of dominating the environment (in order to extract natural resources or to minimise disruption to our daily schedules of work and leisure) seems perfectly natural in spite of the catastrophic consequences for future life on earth (Bookchin 1991). Strategies for economic, technical and social innovation that fixate on establishing ever more efficient and productive systems of control and growth, deployed by fewer, more centralised agents have been shown conclusively to be both unjust and environmentally unsustainable (Jackson 2009). Humanity needs new strategies for social and material renewal and to develop more diverse and lively ecologies of ideas, occupations and values.

In critical media art culture, where artistic and technical cultures intersect, alternative perspectives are emerging in the context of the collapsing natural environment and financial markets; alternatives to those produced (on the one hand) by established ‘high’ art-world markets and institutions and (on the other) the network of ubiquitous user owned devices and corporate social media. The dominating effects of centralised systems are disturbed by more distributed, collaborative forms of creativity. Artists play within and across contemporary networks (digital, social and physical) disrupting business as usual and embedded habits and attitudes of techno-consumerism. Contemporary cultural infrastructures (institutional and technical), their systems and protocols are taken as the materials and context for artistic and social production in the form of critical play, investigation and manipulation.

This essay presents We Won’t Fly for Art, a media art project initiated by artists Marc Garrett and I in April 2009 in which we used online social networks to activate the rhetoric of Gustav Metzger’s earlier protest work Reduce Art Flights (from 2007) in order to reduce art-world-generated carbon emissions... Download full text (pdf- 88Kb) >

Published in PAYING ATTENTION: Towards a Critique of the Attention Economy

Special Issue of CULTURE MACHINE VOL 13 2012 by Patrick Crogan and Samuel Kinsley.

Featured image: Environmental Risk Assessment Rover – ERAR – AT (2008) Mobile, Solar Powered, Networked Installation Off the Grid, Neuberger Mus

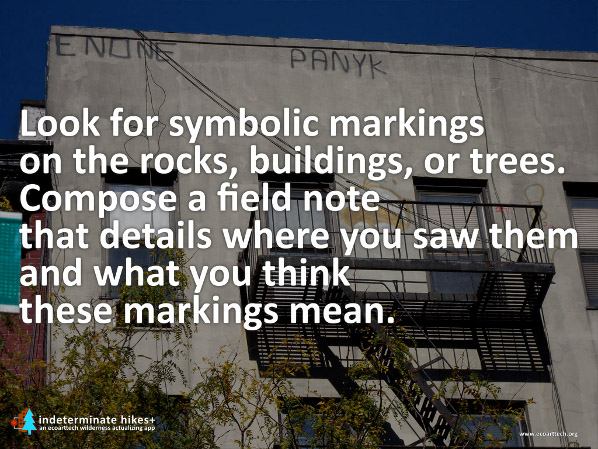

Refusing to regard technology merely as a tool, Ecoarttech expand the uses of mobile technology and digital networks revealing them to be fundamental components of the way we experience our environment. Their most recent work Indeterminate Hikes + (IH +) is a phone app that maps a series of trails through the city. IH + can be accessed globally, or wherever users have access to Google Maps on their mobile phones. After identifying the users’ location, IH + generates a route along random “Scenic Vistas” within urban spaces. Users are directed to perform a series of tasks along the trail and provide feedback in the form of snapshots generating an ongoing, open-ended dialogue.

But the experience of their work is primarily an encounter with technology. Since 2005, Leila Nadir and Cary Peppermint of Ecoarttech have been engaged in an artistic exploration of environmental sustainability and convergent media. By drawing our attention to the increasing replacement or mediation of physical experiences by technology, Ecoarttech challenge the widely reproduced distinction between nature and culture. They present their work in the form of videos, digital networks, blogs, performance and installations. Their early video-based work (Wilderness Trouble and Frontier Mythology) plays out a performative and ironic encounter with the natural environment as a historically constructed concept. In the summer of 2005 Ecoarttech made A Series of Practical Performances in the Wilderness (2005) a database networked performance in QuickTime (DVD and Podcast). The short clips document what Ecoarttech ironically describe as “the experiences of two New Yorkers embarking on their first four months in the woods“. Their objectives were nothing short of

…establishing a functional home without running water, electricity, or maintained roads; developing relationships with locals; un-learning the romanticization of nature while re-learning humanity’s dependence on the environment for survival; and researching the details of the history of the land and the surrounding area.

Sophia Kosmaoglou: The confrontation with the concept of “wilderness” appears to motivate much of your work to date. How did A Series of Practical Performances in the Wilderness begin and how did you fare?

Leila Nadir and Cary Peppermint: About eight years ago, we were very fortunate to acquire a primitive cabin on 50 acres of wild, wooded land, and the experiences we had there changed us completely. Each time we drove from NYC to our “camp” as the locals called it, we were immobilized for about 3-4 days, hardly able to move our bodies as our nervous systems screeched to a halt, adjusting to the quiet. We found a freedom in the woods that we couldn’t find the city – the freedom to take up space, to play, to be quiet, slow, and still. We were also amazed by how some people in the country could seemingly live more independently from bloated global economic systems, growing their own food, chopping their own fuel, harvesting solar energy. They interacted directly with the natural environment whereas we had spent our entire lives ecologically infantilized by overdependence on the industrial grid. We began spending several months at a time at our cabin in the woods: A Series of Practical Performances in the Wilderness is a document of our environmental adventures at that time. It was our first attempt at making art in remote, wilderness spaces. It was a sort of performance of ecological/cultural collision.

SK: How did this experience inform your subsequent work?

LN & CP: As we began to study environmental theory, we realized that not only does little “true” wilderness actually exist, the myth of wilderness was used to obscure the history of indigenous people living on the North American continent. Our own land, we learned, had once been a pasture and had been logged numerous times. Coming to terms with the fact that we hadn’t really retreating to “nature” was the focus of our video Wilderness Trouble which attempts to imagine a new kind of environmental ethics that includes urban and electronic spaces and modern networked culture. However, we still believe that wilderness provides a lot of imaginative potential. Amazement at sublime landscapes can provoke an emotional response that can be politically motivating, and we have tried to take advantage of that potential in our smartphone app Indeterminate Hikes +. By importing the rhetoric of wilderness into everyday life through Google-mapped hiking trails, the app attempts to inspire a sense of ecological wonder at usually disregarded spaces, such as city sidewalks, alleyways, and apartment buildings. We wanted to see what would happen if a walk down a sidewalk were treated as a wilderness excursion. What if we consider the water dripping off an air-conditioner with the same attention that we give a spectacular waterfall in the wilderness?

SK: There is a recurring effort in your work to question the opposition between environment and technology, which is usually accompanied by an ironic undercurrent in your narration and editing that acknowledges what you call “cultural collision”. In Google is a National Park and Nature is a Search Engine which is also part of a series of performances called Center for Wildness in the Everyday (2010), itself conceived as an ecosystem, you suggest that an “environment” is a network of relationships common to natural as well as technological systems, whether it is the ecosystem of a river estuary or Google. Do you see this as a sustainable analogy or a productive contradiction?

LN & CP: Part of what we find frustrating about a lot of environmental thought is that it either wholly rejects technology as the cause of ecological crises so our only solution is to go primitive or wholly embraces technological progress as a saviour, which often means we have to trust in corporate and scientific innovation to lead the way. We think there is another way. We see humans as essentially technical beings: human-animals literally cannot survive without technics. The U.S. military survival guide comes right out and admits that your situation is pretty hopeless if you are stranded in the wilderness without at least a knife. If technology is part of who we are – and we find Bernard Stiegler’s work helpful for thinking this through – then we have also evolved with technology. We are not the same sorts of humans as, for example, Leila’s great-grandmothers in Slovakia or Afghanistan a century ago. The question, then, is not, Yes or No to Technology, but rather, How do we engage technology sustainably and in a way that supports creativity and freedom? And if human beings are technical beings, relying on nature and culture simultaneously, is it even possible to distinguish between what’s natural and what’s not? Isn’t our sustenance dependent upon not only our biological needs (clean air, water and food) but also our cultural practices, beliefs, and imagination? This is why we find it essential to think about electronic spaces and digital technologies whenever we think about the “environment.”