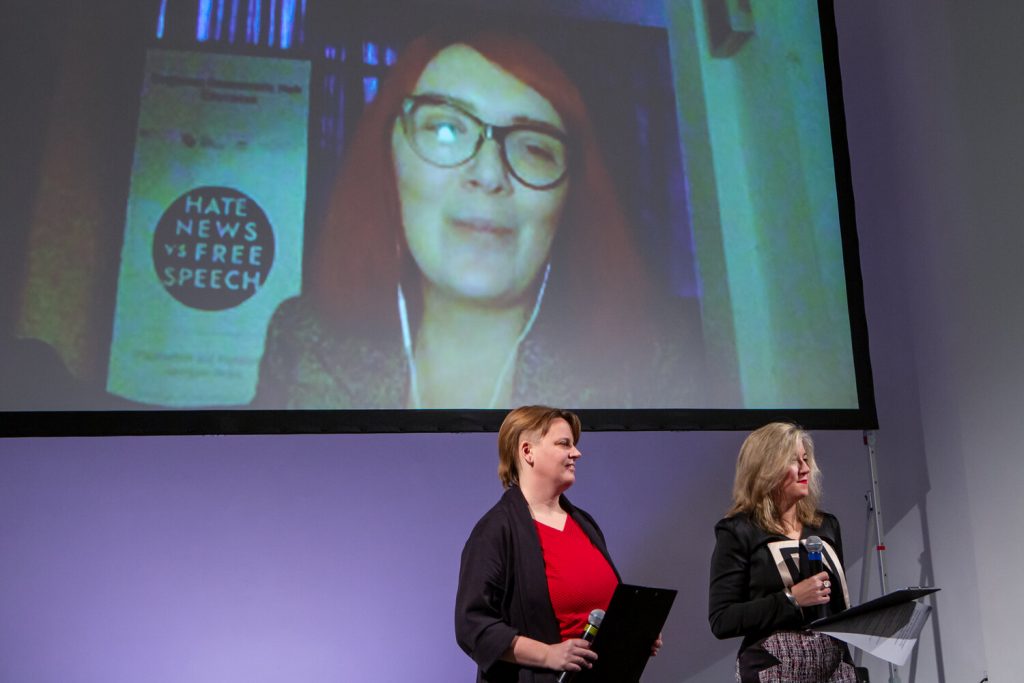

The 22nd conference of the Disruption Network Lab, “HATE NEWS vs. FREE SPEECH”, explored polarization and pluralism in Georgian media, opening on 12 December 2020 in partnership with the Regional Democratic Hub – Caucasus.

Introduced by Tatiana Bazzichelli and Lieke Ploeger, the Programme and Community Director of the Disruption Network Lab, the two-day-event brought together journalists, activists and experts from based in Georgia and Germany to look into the manifestations as well as the consequences of information manipulation and deliberate hate speech within the Georgian media landscape.

The conference, held at Kunstquartier Bethanien in Berlin as a combination of online and on-site formats, investigated a hyper-polarised system, in which exploitative manipulation of facts and orchestrated attempts to mislead people through delivering false information are dangerously eroding media independence, pluralism and freedom of speech. In the context of deliberate technology-fuelled disinformation, spread by news outlets of religious and political influence, hostile countries and other malign sources, the work of independent Georgian journalists is often delegitimised by public authorities and denigrated in a wave of generalisations against media objectivity, to undermine independent information and stifle criticism.

As Bazzichelli stressed in her introductory statement, independent journalists reporting on information that is in the public interest are targeted because of the role they play in ensuring an informed society. At the same time, a global process of mystification is progressively blurring the boundary between what is false and what is real, growing to such a level that traditional media seems incapable of protecting society from a tide of disinformation, and becomes part of the problem.

Opening the first panel, “Polarization and Media Ethics in Georgia”, the moderator Maya Talakhadze, Co-Founder of the Regional Democratic Hub – Caucasus explained that, similar to other former Soviet Union countries, the political environment in Georgia has been polarized since the independence of the country. This has led to highly partisan media and to a marked divergence of political attitudes to ideological extremes within the around 3.7 million Georgians. Although the widespread of the internet guaranteed access to new media outlets and social media opened the way to a more pluralistic media environment, Georgian society soon faced the new challenges of widespread online disinformation, ethics violations and hate speech.

Professor Tamar Kintsurashvili, Executive Director of the Media Development Foundation and Associate Professor at Ilia State University, referred to Georgia as the country with the most pluralistic and free media environment in South Caucasus region. Nevertheless, according to Freedom House and Reporters Without Borders, its information system appears weaker and weaker, public broadcasters have been accused of favouring the government and lawmakers have repeatedly attempted to restrict freedom of expression.

Professor Kintsurashvili stressed how such an environment cannot be considered independent and negatively contributes to the polarization of the country. In her critical analysis, Georgian media pluralism could be described as the product of competing political interests, rather than a sign of strong freedom of expression and an independent press in the country. Despite this, Georgian civil society is widely praised for its diversity and strength.

In Georgia, most media have a political affiliation and align themselves with the agenda of a candidate or a party. This results in the actual instrumentalization of mainstream media and the concentration of ownership of TV stations, online media outlets and newspapers in the hands of the dominant political parties, which are shaping the overall media environment.

Professor Kintsurashvili recalled that in 2017 the ownership of pro-opposition Georgian TV channel Rustavi 2 was transferred to the businessman Kibar Khalvashi, its previous owner, after a ruling by the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR). The case is instructive of the complexity of the Georgian media landscape. Khalvashi’s opponents accused him of having close ties to the government and warned that the new ownership could not guarantee freedom of expression and independence for journalists and broadcasts. Following the ECHR ruling, two new opposition broadcasters emerged.

Professor Kintsurashvili highlighted that, to come to a full understanding of the country, one must consider the possible sympathies of the Georgian politicians toward the Russian Federation, despite the 2008 war and its continuous interferences in domestic affairs.

Many critical voices and independent investigations observe that Russia is supporting a galaxy of media outlets active all over the Caucasus, characterised by a lack of transparency and accountability. These actors promote anti-Western propaganda and are partially responsible for the radicalisation and antagonization of the Georgian society, leveraged to disrupt social cohesion and push the country away from the EU’s Eastern Partnership with the six countries of its Eastern neighbourhood –Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine.

Professor Kintsurashvili points out that while outlets such as Sputnik or Russia Today are openly funded by the Russian government or by Russian oligarchs, the ownership structures of dozens of online platforms remain unclear, and many vanish after a few weeks of activity.

In addition to this, the panellist considered that economic resources for independent media are limited and a lack of transparency of financing – especially in online media – which poses a serious problem for the independence and impartiality of many media outlets, as they are not accountable to the Georgian public but to their owners. Neutral newsrooms with no political affiliation are not self-sufficient and manage to have a small impact on the overall environment; nothing compared to big TV channels, which remain the major source of information in the country.

Taking a step from such a polarized environment shaped by domestic and foreign actors with a political agenda, the second panellist Nata Dzvelishvili, Executive Director at Indigo Publishing, focused on the current state of media ethics in Georgia and the lack of media literacy among Georgians. She considered that, in such a polluted disinformation ecosystem, the majority have almost no reliable instruments to orientate and discern good independent journalism, fake news and poor-quality reporting, which means also that the capability to identify verifiable information in the public interest, and information that does not meet precise ethical standards, is limited.

Dzvelishvili is the former Executive Director of the Georgian Charter of Journalistic Ethics, the self-regulatory body of media in Georgia. She pointed out that by decoding the authenticity of online news we can see how, alongside with the so-called fake news, there is also an alarming degree of laxity and journalistic errors arising from poor research and superficial verification. She listed a few frequent unethical behaviours and violations, from the lack of accuracy to unprofessional coverage of facts reported to arouse curiosity or broad interest through the inclusion of exaggerated or lurid details. In Georgia, this last aspect is mirrored in an unfair and hyper-partisan selection of facts, too.

The Georgian Charter of Journalistic Ethics – a body composed of 400 member journalists, which processes complaints and makes decisions on issues regarding ethical standards and principles – warned that Georgian media too often spread news based on unverified facts, or even simple errors, generating misinformation. Bad information undermines the credibility of media, and unprofessional journalism opens the way for widespread disinformation and misinformation.

Dzvelishvili explained that in Georgia the most critical topics subject to manipulation due to political interest are those related to religious sentiment, LGBTQI identities, migration and nationalism. In her intervention she presented examples of campaigns fuelling homophobia, racism and reopening historic traumas, fruitful ground for the growth of ultra-nationalistic, conservative, and pro-Russian narratives.

Many of the media outlets accused of spreading anti-Western and pro-Russian propaganda acted all over the Caucasus to disseminate disinformation about Georgia’s position on the Karabakh conflict, and thus foster hostility between ethnic Armenian, Azerbaijani and Georgian populations. Rumours and fully fabricated stories about Georgian Muslims ready to gain independence led to the concrete risk of a conflict between ethnic Georgians, the religious orthodox and Muslims, and represented a new pretext to call for Russian intervention to resolve the conflict. More recently, the COVID-19 pandemic was used to fuel anti-Western feelings, provoke mistrust in science, discredit Western democracies and divide the country.

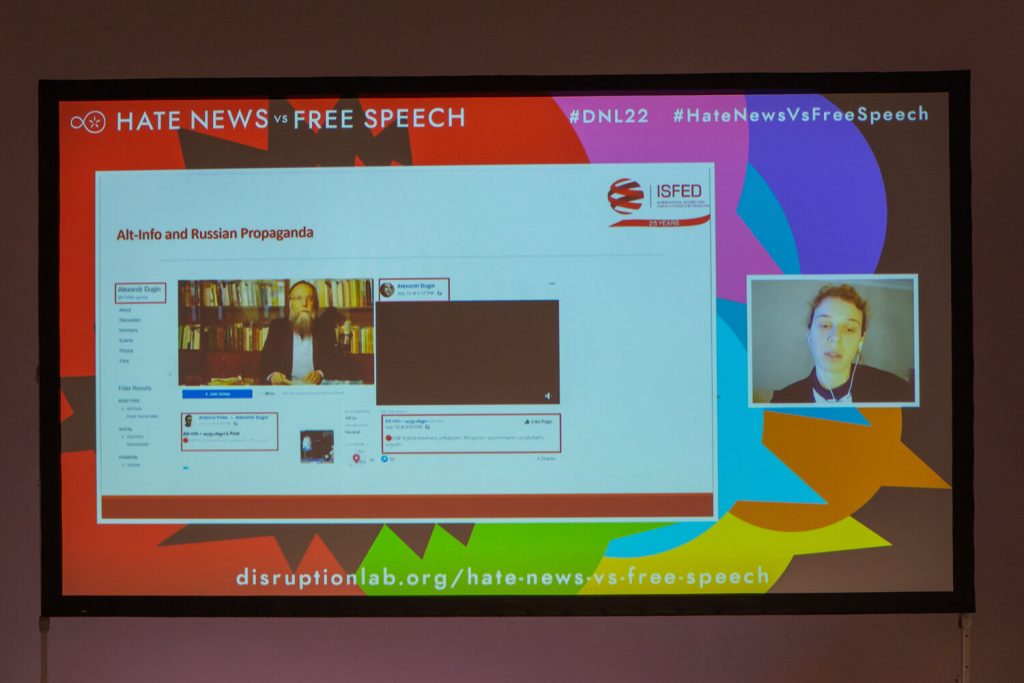

Nini Gvilia, Project Assistant for Social Media Monitoring at the International Society for Fair Elections and Democracy (ISFED), focused on social media in Georgia, which – she explained – 20 percent of the population use as their main source of information. Political activities have strongly shifted to Facebook and other social media, with the support of agencies such as The Marketing Heaven, which enables a more pluralised information environment but also sharpens the risk of misuse by malign actors.

News Front, a Georgian-language website, is one of these. Facts can be irrelevant against a torrent of abuse and hatred towards journalists and opponents, made possible by algorithms, fake accounts, coordinated bots and trolls, that generate viral postings on social media. News Front has also been active on Facebook since 2019. Analysing the interactions of its audience, it is observable that manipulation also arises by weaponizing memes to propel hate speech and denigration or creating false campaigns to distract public attention from actual news. Marginal voices and fake news can be disseminated by inflating the number of shares with automated or semi-automated accounts, which manipulate public opinion by boosting the popularity of online posts and amplifying rumours.

Many Georgians are still anchored to very traditionalist and conservative beliefs. Groups of right-wing extremists offer appealing online spaces filled with redundant rhetoric, gossip columns, sport blogs, and other apparently harmless content, which actually underpins anti-liberal, misogynistic, racist and homophobic views, pushing for a new authoritarian turnaround. Too often, mainstream TV channels and newspapers pick up staged news from such a disinformation ecosystem, enforcing a revisionist narrative built on manipulated facts and fake interactions, arrogance and violence.

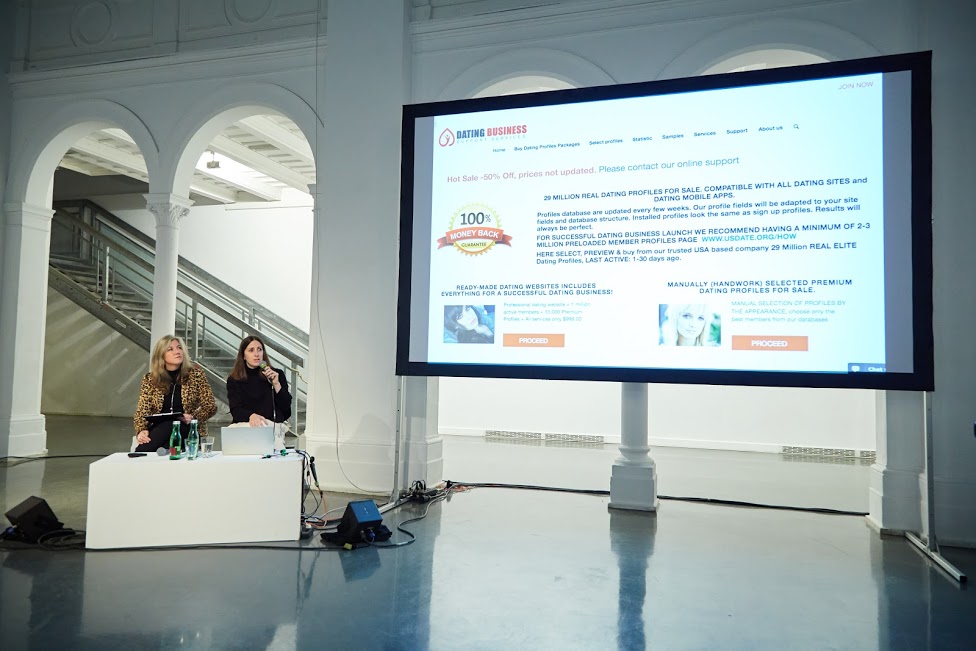

Eka Rostomashvili, Advocacy and Campaigns Coordinator at Transparency International, moderated the panel “Misinformation on Social Media during Elections”. The opening contribution by Varoon Bashyakarla, Data Scientist at Tactical Tech’s Data & Politics Project, focused on how the ‘digital influence industry’operates. In addition, Bashyakarla dissected some of the dynamics that allow personal data to be weaponised for political purposes.

As he recalled, personal data of potential electors is being used constantly for political purposes – even without a precise agenda, just to spread disinformation. Hundreds of companies around the world profile people to influence and predict their political choices. Working with journalists, academics, and civil society organisations, Bashyakarla underlined how these tech firms exploit personal information as a political asset and source of political intelligence.

Many countries traditionally hold voter rolls containing basic information of their electors. Voters’ data is at the heart of modern campaigning and many of the companies working in consumers tech have opened new divisions dedicated to political technology – a term commonly used in the former Soviet states for a highly developed industry of political manipulation – to build statistical models that spy on voters to learn from their preferences and characteristics. Cambridge Analytica was just one of the many entities collecting and misusing intimate personal data to target and manipulate the electorate.

Last year, personally identifiable information of 4.9 million Georgians from 2011 appeared online. Many suspected that the leak was triggered to undermine voters’ faith in elections. However, a leak consisting of 200 million US-American voter files, with personal data including ethnicity and religion, had already demonstrated in 2017 – illustrating how risky election tech can be. The same happened in the Philippines, where the website of the government was subject to a cyber-attack and 340 gigabytes of the personal details of 55 million voters appeared online, and in Turkey, where in 2016 a leak of a 6.6 gigabyte file made available information of 50 million voters.

Bashyakarla discussed then how the extraction of value from political data works and explained the logic behind A/B testing, deployed to compare the performance of two competing advertisements. He warned that societies around the world are exposed to an unprecedented volume of testing. During the last US elections, for example, on the day of the third presidential debate a single online content could be shared in up to 175,000 different variations to test the reaction of the electorate.

Politicians test their postings, images, headlines and slogans to learn in which areas voters are more sympathetic to their messages; what causes in different regions of the country they care more about; and what topics are more likely to be appreciated by a specific audience. As Facebook suggests in one of its advertisements, these techniques allow you to “find the perfect match between your ad and your audience.”

In Georgia, the volume of unsolicited texting and even phone calls spreading political messages that electors receive before elections is overwhelming. Both pro-government political parties and opposition parties deploy similar tactics, which reach their peak point during elections. Coinciding with this very intense activity, the number of online pages spreading fake news triples, with hatred campaigns amplifying differences and fuelling polarization.

Mikheil Benidze, Chief of Party for the new Georgia Information Integrity Program at the Zinc Network, shared his observations on how social media platforms have been weaponized for electoral purposes and how Georgian civil society has risen to the challenge. In the next few years, the Georgia Information Integrity Program, run by the Zinc Network, is going to look into the activities of online users, to research why certain narratives are successful and what their actual impact is.

Benidze recalled that the web is full of traps, like fake news websites that look like the online version of mainstream newspapers, and TV channels, which deceive readers. These fake websites are used to co-ordinate campaigns and networks of political influence, propagate nationalistic, xenophobic, and homophobic content and to undermine the development of a multicultural liberal democracy. The panellist considered that algorithms amplify those messages even more, and praised Georgian civil society organisations for constantly debunking, exposing and analysing facts to protect a free, democratic and open debate. People get spontaneously together and mobilise to strengthen independent fact-checking initiatives and encourage the co-operation with social networks to monitor and delate online harmful content.

The panel was concluded by the contribution of Rafael Goldzweig, Research Coordinator at Democracy Reporting International, an independent non-profit organisation based in Berlin, which promotes political participation of citizens, accountability of state bodies and the development of democratic institutions worldwide. Goldzweig compared the trends observed in Georgia described throughout the first day of the conference with what happens in other countries. He offered an overview of regulatory approaches and initiatives – particularly those debated in the European Union – for making the online environment more resilient against disinformation, hate speech and other challenges.

The digital sphere and its interactions proved to be able to determine the course of elections and host activities, which can undermine the stability of a fragile institutional system. The researcher pointed out that, all over the world, social media has become subject to electoral observation, too, to monitor the rights of candidates and of the electorate.

Goldzweig is confident that more organisations and actors around the world can replicate the monitoring activities of Democracy Reporting International. He suggested that transparency and monitoring are fundamental to understand what happens online, and that we are facing a multi-stakeholder responsibility, since tech companies are asked to provide solutions and governments to maintain a central role. These actors must facilitate the monitoring by civil society and implement tech that enforces community standards able to guarantee individual and collective rights.

The first day’s guests presented a clearer image of the complex situation in the Georgian media landscape, in which disinformation and propaganda seek to animate people into becoming conduits of divisive messages and violence. All panellists expressed concern about the alarming levels of homophobia and xenophobia. Several contributions suggested that journalistic self-regulation and a respect for precise ethical principles appear to be the only way to guarantee strong and free information systems, keeping in mind that Georgian democratic institutions are still fragile and that lawmakers will try to implement new regulations as a leverage to limit freedom of expressions.

The conference’s closing panel, “Hate Speech & Human Rights”, was moderated by performer and journalist Azadê Peşmen. The talk opened with a focus on hate speech, violence and discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity in Georgia.

Giorgi Tabagari, Co-Founder and Director of Tbilisi Pride, gave the audience the chance to learn more about LGBTQI rights in the country. Georgian legislation directly prohibits discrimination against all LGBTQI people, nevertheless – as set out in the previous panels of the conference – there is a high level of hostility against queer people everywhere in Georgian society. Gay and transgender people, along with Jehovah Witnesses, Muslims and Armenians, are publicly presented as national enemies and homosexuality is considered an inexcusable moral corruption.

In Georgia the simple existence of LGBTQI people is a taboo. The mainstream media do not consider sexual and gender identity outside the binary representation of heterosexual men and women. Queer people appear to be the most despised group in the society, which is a fact taken for granted as a normal aspect by most Georgians. Tabagari recalled that an effective way to inflict a damaging insult and to ruin the reputation of a Georgian is to accuse that person of being homosexual: a moral corruption, worse than being a criminal.

The Georgian Orthodox Church has played a defining role in this. Not only does it condemn homosexuality as a sin, but it is also the front line of a violent mobilisation of individuals against queer people. For years, homophobic views have been encouraged by public officials and deployed to delegitimise and discredit political opponents. Investigations found that far-right and hate groups behind these actions were often linked to official parties sitting in the institutions.

By and large, Georgia is a conservative, homophobic country. Many participants of the conference could confirm that less hateful content has been hosted on traditional media in these last two years, whilst social media has been used to build a network of hateful content and online misinformation campaigns targeting LGBTQI activists. Hate and violence have been increasing for a long time, Tabagari warned. Due to more frightening levels of stigma and hatred, LGBTQI people and activists face constant and enormous challenges in Georgian society. Hate crimes and abuses revealed also to significantly increase the risk of poor mental health, from which many queer people suffer. As of today, no statistics about crimes conducted on sexual orientation or gender identity grounds in the country are available. However, it is obvious that the Georgian law prohibiting hate crimes, alone, is not sufficient.

The second panellist, Nino Danelia, Head of Journalism and Media Research at Ilia State University and Founder of the Coalition for Media Advocacy, discussed the implementation of existing national and international human rights standards to combat online hate speech in Georgia.

As described throughout the conference, the Georgian media landscape appears to be a competitive pluralistic system, but highly polarized. Danelia reported that television remains the main source of news and information for the majority of the country, whilst 25 percent of Georgians use internet – and particularly Facebook – to get informed.

On paper, Georgian laws meet international standards, as the country sanctions all forms of expression promoting or justifying racial hatred, xenophobia, and religious based intolerance, including aggressive nationalism and hostility against minorities and migrants.

Hate speech is not criminalised and it is regulated de facto by the Law on Broadcasting and by the Code of Conduct for Broadcasters. Danelia also warned that – in the fragile Caucasian democracy – a new regulation of hate speech could be a threat to media and editorial independence.

Danelia concluded her intervention by explaining that, in her opinion, the issue of polarised, controlled and impartial media can be tackled by strengthening existing self-regulatory mechanisms and funding professional training for journalists. According to the Georgian Charter of Journalistic Ethics, reporters must exert every effort to avoid hate speech that can cause fragmentation and radicalisation of the society.

Political leaders are asked to be careful and avoid violent and ambiguous expressions in their public speeches – not to facilitate, incite or justify hatred founded on intolerance and identity-based convincement. A delicate aspect is still represented by those political groups that propose to prohibit “offending the religious sensibilities or feelings”, which would constitute an area of legal uncertainty and arbitrariness, negatively affecting free speech.

Josephine Ballon, Legal Head at Hate Aid, gave an overview of the German legal perspective on hate speech, beginning from the fact that 78 percent of German internet users have already witnessed hate speech on the internet, whilst 17 percent have been a direct victim of these practices. Researchers calculate that, also in Germany, only 5 percent of users are responsible for almost 50 percent of hateful content.

Balloon recounted an example of neo-Nazis, united under the label “Reconquista Germanica”, and the Austrian Identitarian Movement, pointing out that an official 2019 investigation proved that 70 percent of the hate crimes and hate comments on the internet reported to the authorities were executed by far-right movements.

Such a violent spread of hate intimidates people. Not just those directly targeted, but the majority of internet users admit to being afraid of expressing their political opinions on the internet, fearing the campaigns targeting those who speak out. More precisely, Ballon reported that more than half of the people interviewed do not dare to express political opinions online, as they are afraid of the possible consequences.

The lawyer gives counselling to those who are affected by hatred and discrimination online and teaches them how to protect their data. Personality rights can be defended by directly suing the person responsible of the offence.

Georgian far-right and anti-liberal groups are strong enough to try to influence public opinion, backed by Russian propaganda, and this radicalisation seeks to fragment society even more. Both in Germany and in Georgia, journalistic standards are not applicable to social media and to user-generated content. In 2017, Germany introduced one of the most advanced laws regulating online hate speech at the time, the Network Enforcement Act (NetzDG), requiring internet companies to remove offensive content within 24 hours, or to face up to 50 million euros in fines. Other countries that tried to regulate the same subject ended up approving unconstitutional laws.

The importance of tolerance between diverse groups is stressed in the Georgian national Constitution, which guarantees and defends citizens’ fundamental rights and freedoms. Moreover, the law on broadcasting foresees a ‘National Communications Commission’ to regulate telecommunications and broadcast media. The Commission is supposed to be an independent regulatory body accountable to the legislative, but its practices are often criticised, and it is accused of being loyal to the executive branch.

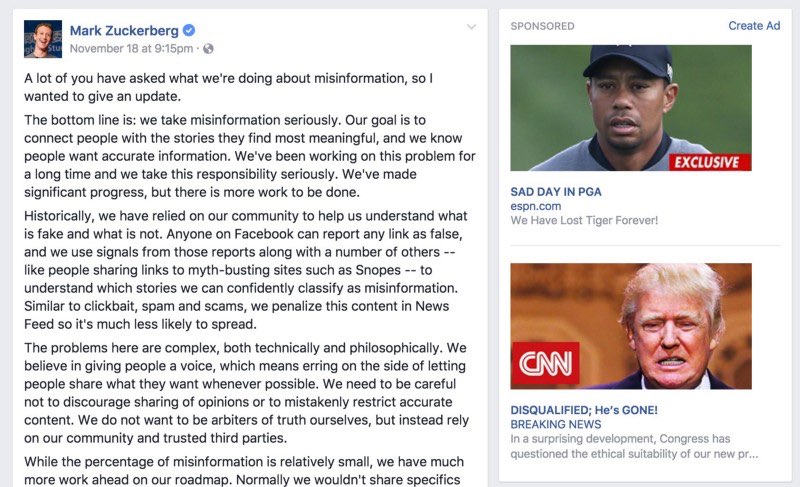

In Georgia, 80 percent of the population who use the internet have a Facebook account. Zuckerberg’s company is the most popular social network in the country. During the last elections, the tech firm came under a lot of pressure from civil society asking to enforce effective measures to stop hate speech and fake news interfering with the democratic process. Twitter is less popular in Georgia, hosting more international users, who mostly write in English. Recently, social media platforms demonstrated themselves to be able to co-operate with local non-governmental organisations to monitor online content. These activities led to ban, and the shut-down of many pages. However, concerns have arisen considering that, between elections, as civil society lets its guard down, those same groups are free to proliferate and spread their content again.

Some keywords resonated throughout the conference, as a fil rouge connecting the speakers and debates held during the panels and commentaries by the public. Participants warned that the era of self-regulation of online social media platforms must come to end, as they have proved that their ruthless interest in clicks, interactions and profit comes before democracy and human rights. For almost a decade now, the spread of disinformation and misinformation through websites, social networks and social messaging has been begging the question of the extent of regulation and self-regulation of the companies providing these services.

On the other hand, the executive and legislative interference in the Georgian courts remains a substantial problem in the country, as does a lack of transparency and professionalism surrounding judicial proceedings. For these reasons, self-regulation remains the only plausible option for editors and journalists.

Media literacy and awareness-raising have been widely recognised as effective and reliable tools to oppose the spread of harmful content and, at the same time, tackle the system of disinformation and violence threatening Georgia. Education, together with strong independent journalists, who know and respect journalistic standards.

On the other hand, we see that economic uncertainties – fear, anger, and resentment – are leveraged to spread campaigns of hatred, attack opponents, discriminate minorities and activists. Conspiratorial, paranoid thinking and violent interactions act like a catalyst, provoking participation and fascinating individuals. Considering that it is all about the benefits of personalised advertising, and ultimately the need for clicks, many observers think that social media will never renounce to such a source of profit.

The collaborative project “HATE NEWS vs. FREE SPEECH: Polarization and Pluralism in Georgian Media” had its first phase between September and October 2020, with two trainings in Georgia on traditional and non-traditional journalism, organised by the Regional Democratic Hub – Caucasus. The announcement of the training triggered high interest, with 120 applications received for 30 places. The first training in Georgia was held in the Kakheti Region involving journalists, (social) media representatives and bloggers from the eastern regions of Georgia. The second training, which took place in October in the Samtskhe Javakheti Region, was held for the students of journalistic faculties with special focus on the regional universities. The training sessions addressed several key areas, among them digital and media literacy, media ethics, hate news and hate speech.

The project ended with this conference and a workshop in Berlin titled “Anatomy of a Conspiracy Theory”, run on December 13 by researcher, trainer and consultant Alistair Alexander, with participants from both Tbilisi and Berlin. The workshop discussed several conspiracy fantasies from around the world, to understand what makes them work and how to challenge their circulation.

HATE NEWS vs. FREE SPEECH provided a forum for discussion and on complex issues, with particular attention for different perspectives of the international guests – especially women – who animated the debate.

For further details of our speakers and topics, please visit the event page: https://www.disruptionlab.org/hate-news-vs-free-speech

The 23rd conference of the Disruption Network Lab, curated by Tatiana Bazzichelli, was titled “Behind the Mask: Whistleblowing During the Pandemic.“ It took place on 18-20 March, 2021.

You can re-watch the panels here: https://www.disruptionlab.org/behind-the-mask

To follow the Disruption Network Lab sign up for the newsletter and get informed about its conferences, meetups, ongoing researches and projects.

The Disruption Network Lab is also on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram.

The 21st conference of the Disruption Network Lab “Borders of Fear” was held on the 27th, 28th, and 29th November 2020 in Berlin’s Kunstquartier Bethanien. Journalists, activists, advocates, and researchers shed light on abuses and human rights violations in the context of migration management policies. Keynote speeches, panel discussions and several workshops were held involving a total number of 18 speakers and bringing together hundreds of online viewers.

Drawing on insights from humanities, science and technology studies, participants analysed from different perspectives the spread of new forms of persecution and border control targeting people on the move and those seeking refuge. They reflected collectively on forms of social justice and discussed the politics of fear that crystalize the stigmatisation of migrants. By concretely addressing these issues the conference also investigated the deployment of technology and the role of media to consolidate a well-defined structure of power, and outlined the reasons behind the rise of borders and walls, factors that lead to cultural and physical violence, persecution, and human rights violations.

In her introductory statement Dr. Tatiana Bazzichelli, founder and director of the Distruption Network Lab, presented the programme of the conference meant to address the discourse of borders both in their material function, and in their defining role within a strategy of dehumanization and racialisations of individuals. Across the globe, an unprecedented number of people are on the move due to war, economic and environmental factors. Bazzichelli recalled the urgent need to discuss human-right-related topics such as segregation and pushbacks, refugee camps and militarization of frontiers, considering the new technological artilleries available for states, investigating at the same time how border policing and datafication of society are affecting the narrative around migrants and refugees in Europe and the in the West.

The four immediate key content takeaways of the first day were the will to prevent people from reaching countries where they can apply for refugee status or visa; the externalisation polices of border control; the illegal practice of pushbacks; and systematic human rights violations by authorities, extensively documented but difficult to prove in court.

The conference opened with the short film by Josh Begley “Best of Luck with the Wall” – a voyage across the US-Mexico border – stitched together from 200,000 satellite images, and a talk by lawyer Renata Avila, who gave an overview of the physical and socio-economic barriers, which people migrating encounter whilst crossing South and Central America.

Avila took step from the current crises in South and Central America, to describe the dramatic migration through perilous regions, a result of an accumulation of factors like inequality, corruption, mafia, and violence. Avila pointed out that oligarchic systems from different countries appear to be interconnected in complicated architectures of international tax evasion, ruthless exploitation of resources, oppression, and the use of force. In those same places, people experience the most brutal inequality, poverty and social exclusion.

Since the ‘90s the regional free trade agreement meant open borders for products but not for people. In fact, it was an international policy with devastating effects on local economies and agriculture. People on the move in search for a better future somewhere else found closed borders and security forces attempting to block them from heading north towards Mexico and the U.S. border. In these years, the police forceful response to the migrants crossing borders have been widely praised by the governments in the region.

The fact of travelling alone is a red flag, especially for women, and the first wall people meet is in their own country. People on their way to the north experience every kind of injustice. Latin America has often been regarded as a region with deep ethnic and class conflicts. Abandoning possible stereotypical representations, we see that the bodies of the people on the move are at large sexualised and racialized for political reasons. Race, therefore, is another factor to consider, especially when we look at the journey of individuals on the move. Aside, languages in South America could also represent a barrier for those who travel without translators in a continent with dozens of indigenous languages.

Avila concluded her intervention mentioning the issue of digital colonialism and the relevance of geospatial data. Digital is no longer a separated space, she warned, but a hybrid one relevant for all individuals and whose rules are dictated by a small minority. People and places can be erased by those very few companies that can collect data, and –for example– draw and delete borders.

The panel on the first day titled “Migration, Failing Policies & Human Rights Violations,” was moderated by Roberto Perez-Rocha, director for the international anti-corruption conference series at Transparency International, and delivered by Philipp Schönberger and Franziska Schmidt, coordinators of the Refugee Law Clinic Berlin, together with investigative journalist and photographer Sally Hayden. The panellists referred to their direct experience and work, and reflected on how the EU migration policy is factually enforcing practices that cause violation of human rights, suffering, and desperation.

The Refugee Law Clinic Berlin e. V. is a student association at the Humboldt University of Berlin, providing free of charge and independent legal help for refugees and people on the move in Berlin and on the Greek island of Samos. The organisation also offers training on asylum and residence law in Berlin and runs the website ihaverights.eu, designed to allow access to justice to those in marginalised communities.

Through a legal counselling project on the Greek island of Samos, the collective helps people suffering from European illegal practices at the Union’s borders, providing the urgent need of effective ways to guarantee them access to justice and protection. As Schönberger and Schmidt recalled, refugees, and people on the move within the EU find several obstacles when it comes to the enforcement of their rights. For such a reason, they shall be guaranteed procedural counselling by the law to secure, among other services, a fair asylum procedure. However, the Clinic confirmed that such guarantees are not being completely fulfilled in Germany, nor at Europe’s borders, in Samos, Lesvos, Leros, Kos, or Kios.

The panellists explained how their presence on the island gives a chance to document that these camps of human suffering are actually a structural part of an EU migration policy aimed at deterring people from entering the Union, result of deliberate political decisions taken in Brussels and Berlin. Human rights violations occur before arriving on the island, as people are intercepted by the Greek coastguard or by the European Border and Coast Guard Agency (Frontex), and then pushed back to the Turkish border.

The camp in Samos, with a capacity of a maximum 648 people, is instead the home to 4,300 residents, with no water, no sanitary services, poisonous food, and no medical services. Even very serious cases documented to local health authorities remain unattended. The list of violations is endless and the complete lack of adequate protection for unaccompanied minors represents another big issue in this like in all others Greek hotspots, together with the precarity of vulnerable groups, whose risks increase with race, gender, and sexual identity.

The legal team from Berlin prepares applications to the EUCHR court and in these years has filed also 60 requests for urgent procedure due to the risk of irreparable harm, which were granted, ordering adequate accommodation and medical treatment for people in extreme danger.

Many observers criticise that the sufferings in the Aegean and on the Greek islands is the result of precise political decisions. Agreed in March 2016, the EU-Turkey deal is a statement of cooperation that seeks to control the crossing of people from Turkey to the Greek islands. According to the deal, every person arriving without documents by boat or without official permission or passage to the Greek islands would be returned to Turkey. In exchange, EU Member States would take Syrian refugees from Turkey. NGOs and international human rights agencies denounce that Turkey, Greece, and the EU have completely failed on humanitarian grounds and dispute the wrong premise that Turkey is a safe country for refugees and asylum-seekers.

Journalist and photographer Sally Hayden looked at the EU-Turkey deal, defining it as a prototype for what would then happen in the central Mediterranean. Libya, a country at war with multiple governments, is the destination of people on move and refugees from all over Africa, willing to cross the Mediterranean Sea. As it is illegal to stop and push people back, for years now the EU has been financing the Libyan coastguard to intercept and pull them back. What follows is a period of arbitrary and endless detention.

Hayden writes about facts; she is not an activist. When she talks about Libya, she refers to objective events she can fact check, and individual stories she has personally collected. Her reports represent a country at war, unsafe not just for refugees and people on the move but for Libyans too. With her work, the journalist has extensively documented how refugees and migrants smuggled into Libya are subject to human trafficking, forced labour, sexual exploitation and tortures, trapped in an infernal circle of violence and death. She recalled her experience with the detainees in Abu Salim, where 500 hundred people suffer from illegal and brutal incarceration inside a centre affiliated with the government in Tripoli. In July 2020, during the conflict, one of these many prisons not far from the city was bombed. At least 53 illegally detained people were killed.

Hayden’s work provides a picture of the results of Europe’s management of the migration crises in the Mediterranean and Northern Africa. EU funds are employed for militarization of borders and externalisation of frontiers control. The political context, in which this occurs, is the cause of years and sometimes decades of lack of investment in reception and asylum systems in line with EU-State’s generic obligations to respect, protect and fulfil human rights.

All panellists called for the immediate intervention to evacuate camps and prisons that were the result of the EU migration policies, to allow migrant victims of abuses and refugees to seek justice and safety elsewhere.

The evening closed with the panel discussion titled “Illegal Pushbacks and Border Violence” and moderated by Likhita Banerji, a human rights and technology researcher at Amnesty International. Banerji reminded the audience that in the first nine months of 2020 there had already been 40 pushbacks, illegal rejections of entry, and expulsions without individual assessment of protection needs, had been documented within Europe or at its external borders. Since these illegitimate practices are widespread, and in some countries systematic, these pushbacks cannot be defined as incidental actions. They appear, instead, to be institutionalised violations, well defined within national policies.

People who shall receive asylum or be rescued, are instead pushed back by police forces, who make sure that the material crossing of the borders remains undocumented. EU member States want to keep undocumented migrants, asylum seekers and refugees outside of their jurisdiction to avoid moral responsibilities and legal obligations. During the second panel of the day, Hanaa Hakiki, legal advisor at the ECCHR Migration Program, filmmaker and reporter Nicole Vögele, and Dimitra Andritsou, researcher at Forensic Architecture, had the chance to go in-depth and to consider the different aspects of these violations.

Hanaa Hakiki, in her intervention “Bringing pushbacks to justice” presented the difficulties that litigators experience in court to materially document pushbacks, which are indeed not meant to be proven. She defined pushbacks as a set of state measures, by which refugees and migrants are forced back over the border – generally shortly after having crossed it – without consideration of their individual circumstances and without any possibility for them to apply for asylum or to put forward arguments against the measures taken.

There are national and international laws that need to be considered in these cases, constituting binding legal obligations for all EU Member States. As a general principle, governments cannot enact disproportionate force, humiliating and degrading treatment or torture, and must facilitate the access to asylum, guarantee protection to people, and provide them access to individualised procedures in this sense.

Member States know that pushbacks have been illegal since a 2012 ECtHR judgment, known as the “Hirsi Jamaa Case,” which found that Italy had violated the law in forcing people back to Libya. However, the effective ban on direct returns led European countries to find other ways to avoid responsibility for those at sea or crossing their borders without documents, and concluded agreements with neighbouring countries, which are requested to prevent migrants from leaving their territories and paid to do so, by any means and without any human rights safeguards in place. By outsourcing rescue to the Libyan authorities, for example, pushbacks by EU countries turned into pullbacks by Libyan coastguard.

Land-pushbacks are still common practice. Hakiki explained that the European Centre for Constitutional and Human Rights (ECCHR) has worked with communities of undocumented migrants since 2014, considering potential legal interventions against the practice of pushbacks at EU borders, and assisting affected persons with individual legal proceedings. She presented three cases the ECCHR litigated in Court (N.D. and N.T. v. Spain; AA vs North Macedonia; SB vs. Croatia) proving that European countries illegally push people back, in violation of human rights laws. Despite the fact that this is still a common practice, it is very difficult to document these violations and have the authorities condemned.

During the beginning of the Syrian conflict, in 2015, refugees were able to travel via Serbia and Hungary into Central and Northern Europe. A couple of years later the EU decided to close down again this so-called Balkan Route, with the result that more and more people found themselves stuck in Bosnia-Herzegovina, prevented from continuing onward to Europe’s territories. From there a person can try to enter the European Union dozens of times, and each time is stopped by Croatian security forces, beaten, and then dragged back across the border to Bosnia-Herzegovina.

After having seen the effects of these illegal practices and met victims of dozens of violent pushbacks in Sarajevo, in 2019 the reporter Nicole Vögele and her crew succeeded in filming a series of these cross-border expulsions from Croatia to Bosnia Herzegovina near the village of Gradina, in the municipality of Velika Kladuša. The reporter, one of the few who succeeded in documenting this practice, also interviewed those who had just been pushed back by the Interventna Policija officers. The response of the Bosnian authorities to her reportage was a complete denial of all accusations.

Vögele then presented footage taken at the EU external border in Croatia, in March 2020, showing masked men beat up refugees and illegally pushing them back to Bosnia. The journalist and her team found the original video, analysed its metadata, and interviewed the man captured on it. Once again, their work could prove that these practices are not isolated incidents.

The panel closed with the investigation by Forensic Architecture part of a broader project on cases of pushbacks across the Evros/Meriç river. Team member Dimitra Andritsou presented the organisation founded to investigate human rights violations using a range of techniques, flanking classical investigation methods including open-source investigation video analysis, spatial and architectural practice, and digital modelling.

Forensic Architecture works with and on behalf of communities affected by state and military violence, producing evidence for legal forums, human rights organisations, investigative reporters and media. A multidisciplinary research group – of architects, scholars, artists, software developers, investigative journalists, archaeologists, lawyers, and scientists – based at the University of London, works in partnership with international prosecutors, human rights organisations, political and environmental justice groups, and develops new evidentiary techniques to investigate violations of human rights around the world, armed conflicts, and environmental destruction.

The Evros/Meriç River is the only border between Greece and Turkey that is not sea. For years migrants and refugees trying to cross it to enter Europe have been reporting that unidentified and generally masked men catch, detain, beat, and push people back to Turkey. Mobile phones, documents, and the few personal things they travel with are confiscated or thrown into the river, not to leave any evidence of these violations behind. As Andridsou described, both Greek and EU authorities systematically deny any wrongdoing, refusing to investigate these reports. The river is part of a wider ecosystem of border defence and has been weaponised to deter and let die those who attempt to cross it.

In December 2019, the German magazine Der Spiegel obtained rare videos filmed on a Turkish Border Guard’s mobile phone and on a surveillance, camera installed on the Turkish banks of the river, which apparently documented one of these many pushback operations. Forensic Architecture was commissioned to analyse the footages. A team of experts was then able to geolocate and timestamp the material and could confirm that the images were actually taken few hundred metres away from a Greek military watchtower in Greece.

Andritsou then presented the case of a group of three Turkish political asylum seekers, who entered Greek territory on 4 May 2019, always crossing the Evros/Meriç river. In this case a team of Forensic Architecture could cross-reference different evidence sources, such as new media, remote sensing, material analysis, and witness testimony and verify the group’s entry and their illegal detention in Greece. A pushback to Turkey on the 5 May 2019 led to their arrest and imprisonment by the Turkish authorities.

Ayşe Erdoğan, Kamil Yildirim, and Talip Niksar had been persecuted by the Turkish government on allegations of involvement in Fettulah Gulen’s movement. The group on the run had shared a video appealing for international protection against a possible forced return to Turkey and digitally recorded the journey via WhatsApp. All their text messages with location pins, photographs, videos and metadata prove their presence on Greek soil, prior to their arrest by the Turkish authorities. The investigation could verify that the three were in a Greek police station too, a fact that matches their statement about having repeatedly attempted to apply for asylum there. Their imprisonment is a direct result of the Greek authorities contravening the principle of non-refoulement.

Some keywords resonated throughout the first day of the conference, as a fil rouge connecting the speakers and debates held during the panels and commentaries by the public. Violence, arbitrariness and lawlessness are wilfully ignored –if not backed– by EU Member States, with authorities constantly trying to hide the truth. Thousands of people live under segregation, with no account or trace of being in custody of authorities free to do with them whatever they want.

Technology has always been a part of border and immigration enforcement. However, over the last few years, as a response to increased migration into the European Union, governments and international organisations involved in migration management have been deploying new controversial tools, based on artificial intelligence and algorithms, conducting de facto technological experiments and research involving human subjects, refugees and people on the move. The second day of the conference opened with the video contribution by Petra Molnar, lawyer and researcher at the European Digital Rights, author of the recent report “Technological Testing Grounds” (2020) based on over 40 conversations with refugees and people on the move.

When considering AI, questions, answers, and predictions in its technological development reflect the political and socioeconomic point of view, consciously or unconsciously, of its creators. As discussed in the Disruption Network Lab conference “AI traps: automating discrimination” (2019)— risk analyses and predictive policing data are often corrupted by racist prejudice, leading to biased data collection which reinforces privileges of the groups that are politically more guaranteed. As a result, new technologies are merely replicating old divisions and conflicts. By instituting policies like facial recognition, for instance, we replicate deeply ingrained behaviours based on race and gender stereotypes, mediated by algorithms. Bias in AI is a systematic issue when it comes to tech, devices with obscure inner workings and the black box of deep learning algorithms.

There is a long list of harmful tech employed at the EU borders is long, ranging from Big Data predictions about population movements and self-phone tracking, to automated decision-making in immigration applications, AI lie detectors and risk-scoring at European borders, and now bio-surveillance and thermal cameras to contain the spread of the COVID-19. Molnar focused on the risks and the violations stemming from such experimentations on fragile individuals with no legal guarantees and protection. She criticised how no adequate governance mechanisms have been put in place, with no account for the very real impacts on people’s rights and lives. The researcher highlighted the need to recognise how uses of migration management technology perpetuate harms, exacerbate systemic discrimination, and render certain communities as technological testing grounds.

Once again, human bodies are commodified to extract data; thousands of individuals are part of tech-experiments without consideration of the complexity of human rights ramifications, and banalizing their material impact on human lives. This use of technology to manage and control migration is subject to almost no public scrutiny, since experimentations occur in spaces that are militarized and so impossible to access, with weak oversight, often driven by the private sector. Secrecy is often justified by emergency legislation, but the lack of a clear and transparent regulation of the technologies deployed in migration management appears to be deliberate, to allow for the creation of opaque zones of tech-experimentation.

Molnar underlined how such a high level of uncertainty concerning fundamental rights and constitutional guarantees would be unacceptable for EU citizens, who would have ways to oppose these liberticidal measures. However, migrants and refugees have notoriously no access to mechanisms of redress and oversight, particularly during the course of their migration journeys. It could seem secondary, but emergency legislation justifies the disapplication of laws protecting privacy and data too, like the GDPR.

The following part of the conference focused on the journey through Sub-Saharan and Northern Africa, on the difficulties and the risks that migrants face whilst trying to reach Europe. In the conversation “The Journey of Refugees from Africa to Europe,” Yoseph Zemichael Afeworki, Eritrean student based in Luxemburg, talked of his experience with Ambre Schulz, Project Manager at Passerell, and reporter Sally Hayden. Afeworki recalled his dramatic journey and explained what happens to those like him, who cross militarized borders and the desert. The student described that migrants represent a very lucrative business, not just because they pay to cross the desert and the sea, but also because they are used as cheap labour, when not directly captured for ransom.

Once on the Libyan coast, people willing to reach Europe find themselves trapped in a cycle of waiting, attempts to cross the Mediterranean, pullbacks and consequent detention. Libya is a country at war, with two governments. The lack of official records and the instability make it difficult to establish the number of people on the move and refugees detained without trial for an indefinite period. Libyan law punishes illegal migration to and from its territory with prison; this without any account for individual’s potential protection needs. Once imprisoned in a Libyan detention centre for undocumented migrants, even common diseases can lead fast to death. Detainees are employed as forced labour for rich families, tortured, and sexually exploited. Tapes recording inhuman violence are sent to the families of the victims, who are asked to pay a ransom.

As Hayden and Afeworki described, the conditions in the buildings where migrants are held are atrocious. In some, hundreds of people live in darkness, unable to move or eat properly for several months. It is impossible to estimate how many individuals do not survive and die there. An estimated 3,000 people are currently detained there. The only hope for them is their immediate evacuation and the guarantee of humanitarian corridors from Libya –whose authorities are responsible for illegal and arbitrary detention, torture and other crimes– to Europe.

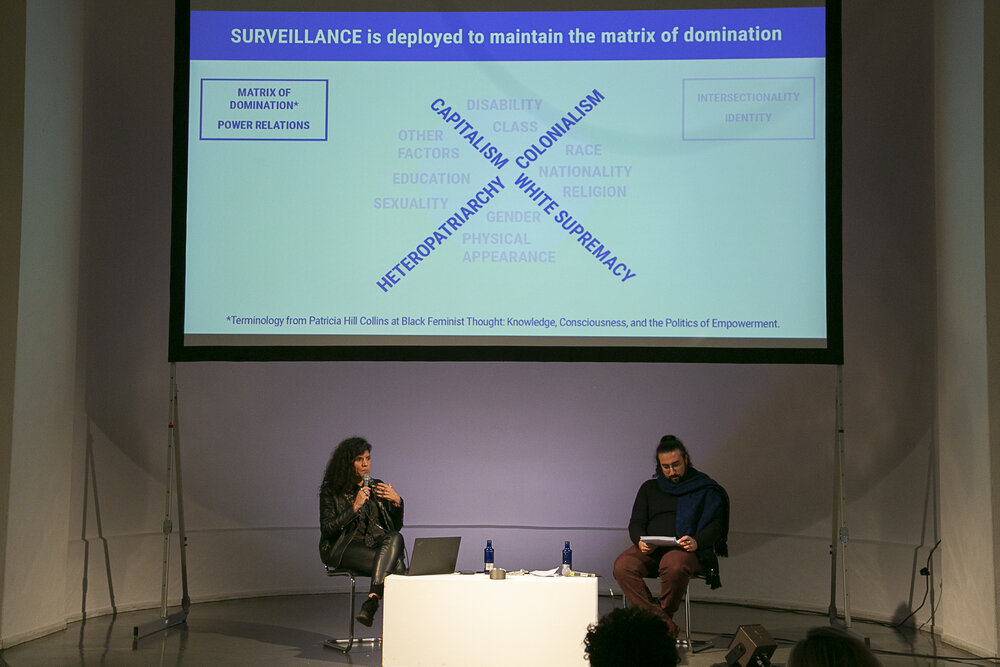

The second day closed with the panel “Politics & Technologies of Fear” moderated by Walid El-Houri, researcher, journalist and filmmaker. Gaia Giuliani from the University of Coimbra, Claudia Aradau, professor of International Politics at King’s College in London, and Joana Varon founder at Coding Rights, Tech and Human Rights Fellow at Harvard Carr Center.

Gaia Giuliani is a scholar, an anti-racist, and a feminist, whose intersectional work articulates the deconstruction of public discourses on the iconographies of whiteness and race, questioning in particular the white narrative imaginary behind security and borders militarization. In her last editorial effort, “Monsters, Catastrophes and the Anthropocene: A Postcolonial Critique” (2020), Giuliani investigated Western visual culture and imaginaries, deconstructing the concept of “risk” and “otherness” within the hegemonic mediascape.

Giuliani began her analyses focusing on the Mediterranean as a border turned into a biopolitical dispositive that defines people’s mobility –and particularly people’s mobility towards Europe– as a risky activity, a definition that draws from the panoply of images of gendered monstrosity that are proper of the European racist imaginary, to reinforce the European and Western “we”. A form of othering, the “we” produces fears through mediatized chronicles of monstrosity and catastrophe.

Giuliani sees the distorted narrative of racialized and gendered bodies on the move to Europe as essential to reinforce the identification of nowadays migrations with the image of a catastrophic horde of monsters, which is coming to depredate the wealthy and peaceful North. It´s a mechanism of “othering” through the use of language and images, which dehumanizes migrants and refugees in a process of mystification and monstrification, to sustain the picture of Europe as an innocent community at siege. Countries of origins are described as the place of barbarians, still now in post-colonial times, and people on the move are portrayed as having the ability to enact chaos in Europe, as if Europe were an imaginary self-reflexive space of whiteness, as it was conceived in colonial time: the bastion of rightfulness and progress.

As Giuliani explained, in this imaginary threat, migrants and refugees are represented as an ultimate threat of monsters and apocalypse, meant to undermine the identity of a whole continent. Millions of lives from the South become an indistinct mass of people. Figures of race that have been sedimented across centuries, stemming from colonial cultural archives, motivate the need to preserve a position of superiority and defend political, social, economic, and cultural privileges of the white bodies, whilst inflicting ferocity on all others.

This mediatized narrative of monsters and apocalypse generates white anxiety, because that mass of racialized people is reclaiming the right to escape, to search for a better life and make autonomous choices to flee the objective causes of unhappiness, suffering, and despair; because that mass of individuals strives to become part of the “we”. All mainstream media consider illegitimate their right to escape and the free initiative people take to cross borders, not just material ones but also the semiotic border that segregate them in the dimension of “the barbarians.” An unacceptable unchained and autonomous initiative that erases the barrier between the colonial then and the postcolonial now, unveiling the coloniality of our present, which represents migration flows as a crisis, although the only crisis undergoing is that of Europe.

On the other side, this same narrative often reduces people on the move and refugees to vulnerable, fragile individuals living in misery, preparing the terrain for their further exploitation as labour force, and to reproduce once again racialized power relations. Here the process of “othering” revivals the colonial picture of the poor dead child, functional to engender an idea of pity, which has nothing to do with the individual dignity. Either you exist as a poor individual in the misery –which the white society mercifully rescues– or as a part of the mass of criminals and rapists. However, these distinct visual representations belong to the same distorted narration, as epitomized in the cartoons published by Charlie Hebdo after the sexual assaults against women in Cologne on New Year’s Eve 2015.

Borders have been rendered as testing ground right for high-risk experimental technologies, while refugees themselves have become testing subjects for these experiments. Governments and non-state actors are developing and deploying emerging digital technologies in ways that are uniquely experimental, dangerous and discriminatory in the border and immigration enforcement context. Taking step from the history of scientific experiments on racialized and gendered bodies, Claudia Aradau invited the audience to reconsider the metaphorical language of experiments that orients us to picture high-tech and high-risk technological developments. She includes instead also tech in terms of obsolete tools deployed to penalise individuals and recreate the asymmetries of the digital divide mirroring the injustice of the neoliberal system.

Aradau studies technologies and the power asymmetries in their deployment and development. She explained that borders have been used as very profitable laboratories for the surveillance industry and for techniques that would then be deployed widely in the Global North. From borders and prison systems –in which they initially appeared– these technologies are indeed becoming common in urban spaces modelled around the traps of the surveillance capitalism. The fact that they slowly enter our vocabularies and daily lives makes it difficult to define the impact they have. When we consider for example that inmates’ and migrants’ DNA is collected by a government, we soon realise that we are entering a more complex level of surveillance around our bodies, showing tangibly how privacy is a collective matter, as a DNA sequence can be used to track a multitude of individuals from the same genealogic group.

Whilst we see hyper-advanced tech on one side, on the other people on the move walk with nothing to cross a border, sometimes not even shoes, with their personal belongings inside plastic bags, and just a smartphone to orientate themselves, and communicate and ask for help. An asymmetry, which is –once again– being deployed to maintain what Aradau defined as matrix of domination: no surveillance on CO2 emissions and environmental issues due to industrial activities, no surveillance on exploitations of resources and human lives; no surveillance on the production of weapons, but massive deployment of hi-tech to target people on the move, crossing borders to reach and enter a fortress, which is not meant for them.

Aradau recalled that in theory, protocols ethics and demands for objectivity are necessary when it comes to scientific experiments. However, the introduction in official procedures of digital tech devices and software such as Skype, WhatsApp or MasterCard or a set of apps developed by either non-state or state actors, required neither laboratories nor the randomized custom trials that we usually associate with scientific experimentation. These heterogeneous techniques specifically intended to work everywhere and enforced without protocols, need to be understood under neoliberalism: they rely on pilot projects trials and cycles of funds and donors, whose goal is every time to move to a next step, to finance more experiments. Human-rights-centred tech is far away.

Thus, we see always more experiments carried out without protocols, from floating walls tech to stop migrants reaching the Greek shores, to debit cards used as surveillance devices. Creative experiments come also with the so-called refugees’ integration, conceived by small-scale injections of devices into their reality for limited periods, with the purpose of speculatively recompose rotten asymmetries of power and injustice. In Greece, as Aradau mentioned, the introduction of Skype in the process of the asylum application became an obstacle, with applicants continually experiencing debilitation through obsolete technology that doesn’t work or devices with limited access, disorientation through contradictory and outdated information.

There is also a factual aspect: old and slow computers, documents that have not been updated or have been updated at different times, and lack of personnel are justified by saying that resources are limited. A complete lack or shortage of funds, which is one other typical condition of neoliberalism, as we can see in Greece. In this, tech recomposes relations of precarity in a different guise.

Aradau concluded her contribution focusing on the technologies that are deployed by NGOs, completely or partially produced elsewhere, often by corporate actors who remain entangled in the experiments through their expertise and ownership. Digital platforms such as Facebook, Microsoft, Amazon, or Google not only shape relations between online users, she warned, but concerning people on the move and refugees too. Google and Facebook –for example– dominate the relations that underpin the production of refugee apps by humanitarian actors.

Google is at the centre of a sort of digital humanitarian ecosystem, not only because it can host searches or provide maps for the apps, but also because it simultaneously intercepts data flows so that it acts as a surplus data extractor. In addition, social networks reshape digital humanitarianism through data extractive relations and provide big part of the infrastructure for digital humanitarianism. Online humanitarianism becomes thus a particularly vulnerable site of data gathering and characterised by an overall lack of resources –similarly to the Greek state. As a result, humanitarian actors cannot tackle the depreciation messiness and obsolescence of their tech and apps.

The last day of the conference concentrated on the urgent need to creating safe passages for migration, and pictured the efforts of those who try to ensure safer migration options and rescue migrants in distress during their journey. Lieke Ploeger, community director of the Disruption Network Lab, presented the panel discussion “Creating Safe Passages”, moderated by Michael Ruf, writer and director of documentary and theatre plays. Ruf´s productions include the “Asylum Dialogues” (2011) and the “Mediterranean Migration Monologues” (2019), which have been performed in numerous countries more than 800 times by a network of several hundred actors and musicians. This final session brought together speakers from the Migrant Media Network (MMN), the Migrant Offshore Aid Station (MOAS), and SeaWatch e.V. to discuss their efforts to ensure safer migration options, as well as share reliable information and create awareness around migration issues.

The talk was opened by Thomas Kalunge, Project Director of the Migrant Media Network, one of r0g_agency’s projects, together with #defyhatenow. Since 2017 the organisation has been working on information campaigns addressed to people in rural areas of Africa, to explain that there are possible alternatives for safer and informed decisions, when they choose to reach other countries, and what they may come across if they decide to migrate.

The MMN team organises roundtable discussions and talks on various topics affecting the communities they meet. They build a space in which young people take time to understand what migration is nowadays and to listen to those, who already personally experienced the worst and often less discussed consequences of the journey. To approach possible migrants the MMN worked on an information campaign on the ethical use of social media, which also helps people to learn how to evaluate and consume information shared online and recognise reliable sources.

The MMN works for open culture and critical social transformation, and provides young Africans with reliable information and training on migration issues, included digital rights. The organisation also promotes youth entrepreneurship “at home” as a way to build economic and social resilience, encouraging youth to create their own opportunities and work within their communities of origin. They engage on conversations on the dangers of irregular migration, discussing together rumours and lies, so that individuals can make informed choices. One very relevant thing people tend to underestimate, is that sometimes misinformation is spread directly by human smugglers, warned Kalunge.

The MMN also provides people from remote regions with offline tools that are available without an internet connection, and training advisors and facilitators who are then connected in a network. The HyracBox for example is a mobile, portable, RaspberryPi powered offline mini-server for these facilitators to use in remote or offline environments, where access to both power and Internet is challenging. With it, multiple users can access key MMN info materials.

An important aspect to mention is that the MMN does not try to tell people not to migrate. European government have outsourced borders and migration management, supporting measures to limit people mobility in North and Sub-Saharan Africa, and it is important to let people know that there are real dangers, visible and invisible barriers they will meet on their way.

Visa application processes –even for legitimate reasons of travel– are very strict for some countries, often without any information being shared, even with people who are legitimately moving for education, to work or get medical treatment. The ruling class that makes up the administrative bureaucracy and outlines its structures, knows that who controls time has power. Who can steal time from others, who can oblige others to waste time on legal quibbles and protocol matters, can suffocate the others’ existence in a mountain of paperwork.

Human smugglers then become the final resort. Kaluge explained also that, at the moment, the increased outsourcing of the European border security services to the Sahel and other northern Africa countries is leading to diversion of routes, increased dangerousness of the road, people trafficking, and human rights violations.

Closing the conference, Regina Catrambone presented the work that MOAS does around the world and the campaign for safe and legal routes that is urging governments and international organisations to implement regular pathways of migration that already exist. Mattea Weihe presented instead the work of SeaWatch e. V., an organisation which is also advocating for civil sea rescue, legal escape routes and a safe passage, and which is at sea to rescue migrants in distress.

The two panellists described the situation in the Central Mediterranean. Since the beginning of the year, over 500 migrants have drowned in the Mediterranean Sea (November 2020). While European countries continue to delegate their migration policy to the Libyan Coast Guard, rescue vessels from several civilian organisations have been blocked for weeks, witnessing the continuous massacre taking place just a few miles from European shores. With no common European rescue intervention at sea, the presence of NGO vessels is essential to save humans and rescue hundreds of people who undertake this dangerous journey to flee from war and poverty.

However, several EU governments and conservative and far right political parties criminalise search and rescues activities, stating that helping migrants at sea equals encouraging illegal immigration. A distorted representation legitimised, fuelled and weaponised in politics and across European society that has led to a terrible humanitarian crisis on Europe’s shores. Thus, organisations dedicated to rescuing vessels used by people on the move in the Mediterranean Sea see all safe havens systematically shut off to them. Despite having hundreds of rescued individuals on board, rescue ships wait days and weeks to be assigned a harbour. Uncertainty and fear of being taken back to Libya torment many of the people on board even after having been rescued. After they enter the port, the vessels are confiscated and cannot get back out to sea.

By doing so, Europe and EU Member States violate human rights, maritime laws, and their national democratic constitutions. The panel opened again the crucial question of humanitarian corridors, human-rights-based policy, and relocations. In the last years the transfer of border controls to foreign countries, has become the main instrument through which the EU seeks to stop migratory flows to Europe. This externalisation deploys modern tech, money and training of police authorities in third countries moving the EU-border far beyond the Union’ shores. This despite the abuses, suffering and human-rights violations; willingly ignoring that the majority of the 35 countries that the EU prioritises for border externalisation efforts are authoritarian, known for human rights abuses and with poor human development indicators (Expanding Fortress, 2018).

It cannot be the task of private organizations and volunteers to make up for the delay of the state. But without them no one would do it.

States are seeking to leave people on the move, refugees, and undocumented migrants beyond the duties and responsibilities enshrined in law. Most of the violations, and the harmful technological experimentation described throughout the conference targeting migrants and refugees, occurs outside of their sovereign responsibility. Considering that much of technological development occurs in fact in the so-called “black boxes,” by acting so these state-actors exclude the public from fully understanding how the technology operates.

The fact that the people on the move on the Greek islands, on the Balkan Route, in Libya, and those rescued in the Mediterranean have been sorely tested by their journeys, living conditions, and, in many cases, imprisoned, seems to be irrelevant. The EU deploys politics that make people who have already suffered violence, abuse, and incredibly long journeys in search of a better life, wait a long time for a safe port, for a visa, for a medical treatment.

All participants who joined the conference expressed the urgent need for action: Europe cannot continue to turn its gaze away from a humanitarian emergency that never ends and that needs formalised rescue operations at sea, open corridors, and designated authorities enacting an approach based on defending human rights. Sea rescue organisations and civil society collectives work to save lives, raise awareness and demand a new human rights-based migration and refugee policy; they shall not be impeded but supported.

The conference “Borders of Fear” presented experts, investigative journalists, scholars, and activists, who met to discuss wrongdoings in the context of migration and share effective strategies and community-based approaches to increase awareness on the issues related to the human-rights violations by governments. Here bottom-up approaches and methods that include local communities in the development of solutions appear to be fundamental. Projects that capacitate migrants, collectives, and groups marginalized by asymmetries of power to share knowledge, develop and exploit tools to combat systematic inequalities, injustices, and exploitation are to be enhanced. It is imperative to defeat the distorted narrative, which criminalises people on the move, international solidarity and sea rescue operations.

Racism, bigotry and panic are reflected in media coverage of undocumented migrants and refugees all over the world, and play an important role in the success of contemporary far-right parties in a number of countries. Therefore, it is necessary to enhance effective and alternative counter-narratives based on facts. For example, the “Africa Migration Report” (2020) shows that 94 per cent of African migration takes a regular form and that just 6 per cent of Africans on the move opt for unsafe and dangerous journeys. These people, like those from other troubled regions, leave their homes in search of a safer, better life in a different country, flee from armed conflicts and poverty. It is their right to do so. Instead of criminalising migration, it is necessary to search for the real causes of this suffering, war and social injustice, and wipe out the systems of power behind them.

Videos of the conference are also available on YouTube via:

For details of speakers and topics, please visit the event page here: https://www.disruptionlab.org/borders-of-fear

Upcoming programme:

The 23rd conference of the Disruption Network Lab curated by Tatiana Bazzichelli is titled “Behind the Mask: Whistleblowing During the Pandemic.“ It will take place on March 18-20, 2021. More info: https://www.disruptionlab.org/behind-the-mask

To follow the Disruption Network Lab sign up for the newsletter and get informed about its conferences, meetups, ongoing researches and projects.

The Disruption Network Lab is also on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram.

On May 29, 2020, the Disruption Network Lab opened its 19th conference, “Evicted by Greed: Global Finance, Housing & Resistance”. The three-day-event was supposed to take place in Berlin in March, on the days of the global call for the Housing Action Days. Instead, it took place online due to ongoing safety concerns relating to the coronavirus pandemic.

Chaired by Tatiana Bazzichelli and Lieke Ploeger, programme and community director of the Disruption Network Lab, the interactive digital event brought together speakers and audience members from their homes from all over the world to investigate how speculative finance drives global and local housing crises. The topic of how aggressive speculative real-estate purchases by shell companies, anonymous entities, and corporations negatively impacts peoples’ lives formed the core conversation for the presentations, panel discussions, and interactive question and answer sessions. The conference served as a platform for sharing experiences and finding counter-strategies.

In her introductory statement, Bazzichelli took stock of the situation. As the pandemic appeared, it became clear worldwide that the “stay-at-home” order and campaigns were not considering people who cannot comply since they haven’t got any place to stay. Tenants, whose work and lives have been impacted, struggle to pay rent, bills, or other essentials, and in many cases had to leave their homes or have been threatened with forced eviction. People called on lawmakers at a national and local level to freeze rent requirements as part of their response to the pandemic, but very few measures have been put in place to protect them. However, scarce and unaffordable housing is neither a new, nor a local problem found in just a few places.

Christoph Trautvetter, public policy expert and German activist of