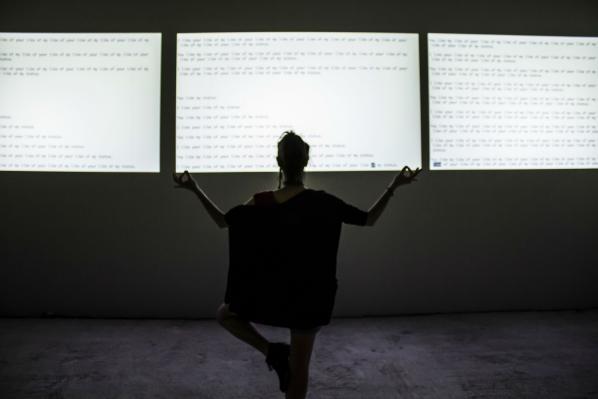

Featured Image: With 69.numbers.suck by Browserbased

Athens Digital Arts Festival (ADAF) returned this year on the 19th to the 22nd of May with its 12th edition to bring Digital Pop under the microscope. Do machines like each other? Does the Queen dream of LSD infused dreams and can a meme be withdrawn from the collective memory?

Katerina Gkoutziouli, an independent curator and this year’s program director together with a team of curators proposed a radical rethinking of digital POP, placing the main focus on the actors of cultural production. From artists to users and then to machines themselves, trends and attitudes shift at high speed and the landscape of pop culture is constantly changing. What we consider POP in 2015 might be outdated in 2016, as the Festival’s program outlines, and that is true. But even so, in the land of memes, GIFs, likes, shares and followers what are the parameters that remain? ADAF’s curatorial line took it a step further and addressed not just the ephemerality of digital POP. It tackled issues related to governance and digital colonialism, but in a subtle and definitively more neon way.

450 artists presented their work in a Festival that included interactive and audiovisual installations, video art, web art, creative workshops and artist talks. Far from engaging in the narrative of crisis as a popular trend itself though, ADAF 2016 was drawn to highlighting the practices that reflect the current cultural condition. And the curated works were dead-on at showcasing those.

How are we “feeding” today’s digital markets then? Ben Grosser’s sound and video installation work “You like my like of your like of my status” screened a progressive generative text pattern of increasingly “liking” each others “likes”. Using the historic “like” activity on his own Facebook account, he created an immersive syntax that could as well be the mantra of Athens Digital Arts Festival 2016.

Days before the opening of the exhibition, Ben Grosser was asked by to choose the image that defines pop the most. No wonder, he replied with the Facebook “like” button. What Ben Grosser portrayed in his work is the poetics of the economy of corporate data collectors such as Facebook with its algorithmic representation of the “Like” button as the king pawn of its toolkit, that transform human intellect as manifested through the declaration of our personal taste and network into networking value.

Speaking of taste, what about the aesthetics? From Instagram and Snapchat filters to ever updated galleries of emoticons available upon request, digital aesthetics are infused with social significance. In the Queen of The Dream by Przemysław Sanecki (PL) the British politics and the Royal tradition were aestheticized by the DeepDream algorithm of Google. In an attempt to relate old political regimes and established technocracies, the artist places together hand in hand the political power with the algorithmical one, pointing out that technologies are essential for ruling classes in their struggle to maintain the current power balance. The representation of the latter was placed there as a reminder that it’s dynamic is to obscure this relation, rather than illuminate it.

However, could there be some space for some creative civil disobedience? Browserbased took us for a stroll in the streets of Athens, or better to say in the public phone booths of Athens. There, the city scribbles every day its own saying, phone numbers for a quick wank, political slogans, graffiti, tags and rhymes. With 69.numbers.suck Browserbased mapped the re-appearance and cross-references of those writings, read this chaotic network of self-manifestation and reproduced it digitally in the form of nodes. Out there in the open a private network emerged, nonsensical or codified, drawn and re-drawn by everyday use, acceptance and decline.

Can virality kill a meme? Yes, there is a chance that the grumpy cat would get grumpier once realized that its image would be broadcasted, connoted and most possibly appropriated by thousands. But how far would it go? The Story of Technoviking by Matthias Fritsch (DE) was showcased at the special screenings session of the Festival. It is a documentary that follows an early successful Internet meme over 15 years from an experimental art video to a viral phenomenon that ends up in court. Once the original footage was uploaded, it remained somehow unnoticed until some years later that it was sourced, shared, mimified, render into art installation, even merchandised by users. As a cultural phenomenon with high visibility it fails to be deleted both from servers around the world and from the collective memory even though that this was a court’s decision. In his work Matthias Fritsch mashes up opinions of artists, lawyers, academics, fans and online reactions marking the conflict between the right of the protection of our personality to the fundamental right of free speech and the direction towards which society and culture will follow in the future in regard to the intellectual property.

It’s the machines alright! Back in the days of Phillip K. Dick’s novels the debate was set over distinctions between human and machine. Since then the plot has thickened and in memememe by Radamés Ajna (BR) and Thiago Hersan (BR) things were taken a step further. This installation, situated in one of the first rooms of the exhibition, of two smartphones seemingly engaged in a conversation between them through and incomprehensible language built on camera shots and screen swipes is based on the suspicion that phones are having more fun communicating than we are. Every message is a tickle, every swipe a little rub. In memememe the fetichized device was not just a mechanic prosthesis on the human body, it was an agent of cultural production. The implication that the human might not cause or end of every process run by machines was promoted to a declaration. Ajna and Hersan have built an app that allows as a glimpse into the semiotics of the machine, a language that we can see but we can’t understand.

How many GIFs fit in one hand? If one were to trace all subcultures related to pop culture, then he or she would have to stretch time. Since they are multiplying, expiring and subcategorized not by theorists but by the users themselves and with their ephemerality condemning most of which into a short lived glory. Lorna Mills (CA) explores the different streams in subcultures through animated GIFs and focuses on found material of users who perform online in front of video cameras. In her installation work Colour Fields she is obsessed on GIF culture, its brevity, compression, technical constraints and its continued existence on the Internet.

Global pop stars, a blueprint on audience development. Manja Ebert (DE) in her interactive video installation ALL EYES ON US, one of the biggest installations of the Festival, embarked on an artistic analysis of the global pop star and media phenomenon Britney Spears. Based on music videos of the entertainer that typecast Spears into different archetypical female characters, Ebert represented each and every figure by a faceless performer. All nine figures were played by a keyboard, thus allowing the users to recompose these empty cells decomposing Spears as a product into its communicational elements.

Going through the festival, more related narratives emerged. Privacy and control, the representation of the self and the body were equally addressed. People stopped in front of the Emotional Mirror by random quark (UK/GR), to let the face recognition algorithm analyze their facial expression and display their emotion in the form of tweets while they were photographing and uploading in one or more platforms the result at the same time.

Τhe Festival presented its program of audiovisual performances at six d.o.g.s. starting on May 19 with the exclusive event focus raster-noton, featuring KYOKA and Grischa Lichtenberger.

ADAF 2016 brought a lot to the table. Its biggest contribution though lies in offering a great deal of stimuli regarding the digital critical agenda to the local digital community. ADAF managed to surpass the falsely drawn conception of identifying the POP digital culture just as a fashionable mainstream. On the contrary it highlights it as a strong counterpoint.