Much of our cultural history of the past two hundred years has been defined by anxieties about the growth of a technological and commercial society. In the nineteenth century, Samuel Taylor Coleridge bewailed ‘the philosophy of mechanism which, in everything that is most worthy of the human intellect, strikes Death’, while Matthew Arnold declared that ‘Faith in machinery is our besetting danger’. For such commentators, culture represented a means of staving off the threat of an industrial society ruled by money and commercialism.

It is easy to fall into a false binary of opposition between art and technology. When pioneering artists and scholars first demonstrated the potential for using computers in arts and humanities research in the period after the Second World War, their work often provoked antipathy because of this anxiety to maintain a distance between art and the machine. In my inaugural lecture at King’s College London in 2012, An Electric Current of the Imagination, I argued that artistic practice offers a particularly effective means of fostering a creative and critical relationship between art and technology. I declared that ‘Such a new conjunction of scientist, curator, humanist, and artist is what the digital humanities must strive to achieve. It is the only way of ensuring that we do not lose our souls in a world of data’.

Since 2012, I have held an AHRC fellowship as Theme Leader Fellow for its strategic theme of ‘Digital Transformations’. One important outcome of this theme has been further exploration of the way in which artistic practice offers innovative perspective on our relationship with technology. Artistic experiments with a range of text technologies from the typewriter to the computer provide exciting insights into the materiality of the text and the way in which text interacts with our senses as readers and writers.

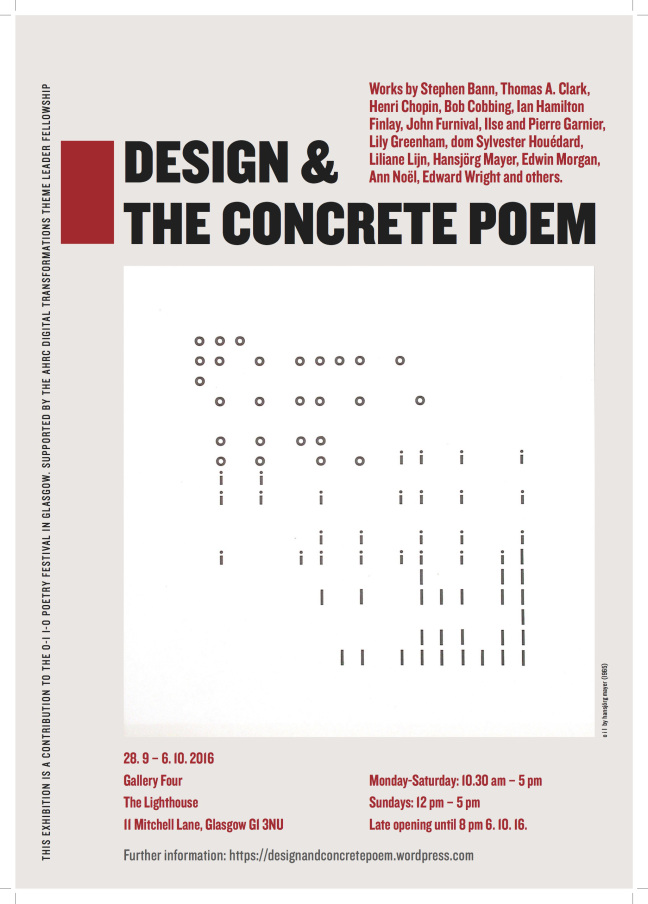

One event held under the auspices of my fellowship which seemed to me to encapsulate these possibilities was an exhibition, Design and the Concrete Poem, curated by Bronac Ferran at the Lighthouse Gallery in Glasgow from 28 September – 6 October 2016. This exhibition introduced me to the work of many artists whose exploration of the materiality of text and poetry I found compelling.

Design and the Concrete Poem introduced me to such reinventions of the text as dom Sylvester Houédard’s experimentation with typewriters or Liliane Lijn’s use of letraset on metal drums to create Poem Machines. The way in which Lijn’s exploration of Dickensian engineering workshops in London in the late 1960s inspired her Material Alphabet (1970), and her fascination with industrial processes and images, epitomises the way in which artistic practice can generate creative conjunctions with technology. Pierre and Ilse Garnier’s poem cut on a Gestetner duplicating stencil, shown for the first time in the Glasgow exhibition, offered both a novel view of textual materiality and an elegy for an obsolete technology.

One artist whose work I have found consistently helpful in thinking about the interaction between technology, communication and our human condition is the Chicago-based Eduardo Kac (b. 1961), and I am delighted to have helped arrange at Furtherfield his first UK show, Poetry for Animals, Machines and Aliens.

Poetry is challenging. A poem questions our certainties, makes us see the world from different angles and, by encouraging us to pause and reflect, subverts that mechanistic goal-oriented outlook which so horrified Coleridge and Arnold but nevertheless dominates the modern world. Technology can give words and letters new shapes and resonances and, in so doing, subvert a consumer-oriented view of technology.

There can be no more imposing expression of technological achievement than the International Space Station. One of the most fascinating aspects of the video of Eduardo Kac’s space poem Inner Telescope, performed in 2016 by the French astronaut Thomas Pesquet, shown in the Furtherfield exhibition, are the interior shots of the cramped space station, jam-packed with wires, containers and panels from innumerable scientific experiments. The confined space station contrasts with the expansive views of the earth visible through the space station windows. This contrast itself seems like a commentary on the puny character of human technological ambitions.

Kac proposed the idea of space poetry in 2007. He pointed out that weightlessness would affect the temporal and physical logic of a poem, while the readers’ sensory engagement with the act of reading would also be different under zero gravity. Inner Telescope vividly illustrates how a simple performance such as cutting paper may be different in zero gravity, while the movement of the paper (cut into a form representing the word ‘Moi’) seems to epitomise the fragility of textual communication. In the rigidly scheduled life of the space station, Inner Telescope uses poetry to pause and reflect on the complex interrelationship of humanity, technology and the wider universe.

One major thread of Kac’s art has been the relentless interrogation of technology to create radical and original poetic visions. Kac experimented with the potential of the typewriter to allow different juxtapositions and textual shapes in his Typewritings of 1981-2 and from these experiments sprang his first digital poem, Não! (No!) , in 1982-4. Não! was presented on an electronic signboard with an LED display with fragmentary text blocks, encouraging the reader to guess at the links between them.

The digital poems shown in the Furtherfield exhibition illustrate how Kac makes use of digital technologies to redefine the relationship between the reader and text and to reveal new poetic elements in short words and phrases. In Accident (1994), a digital loop introduces shifts and uncertainties into a text, recalling the nervous hesitation when two lovers meet, but also causing the reader’s perception of the text to change as the piece progresses.

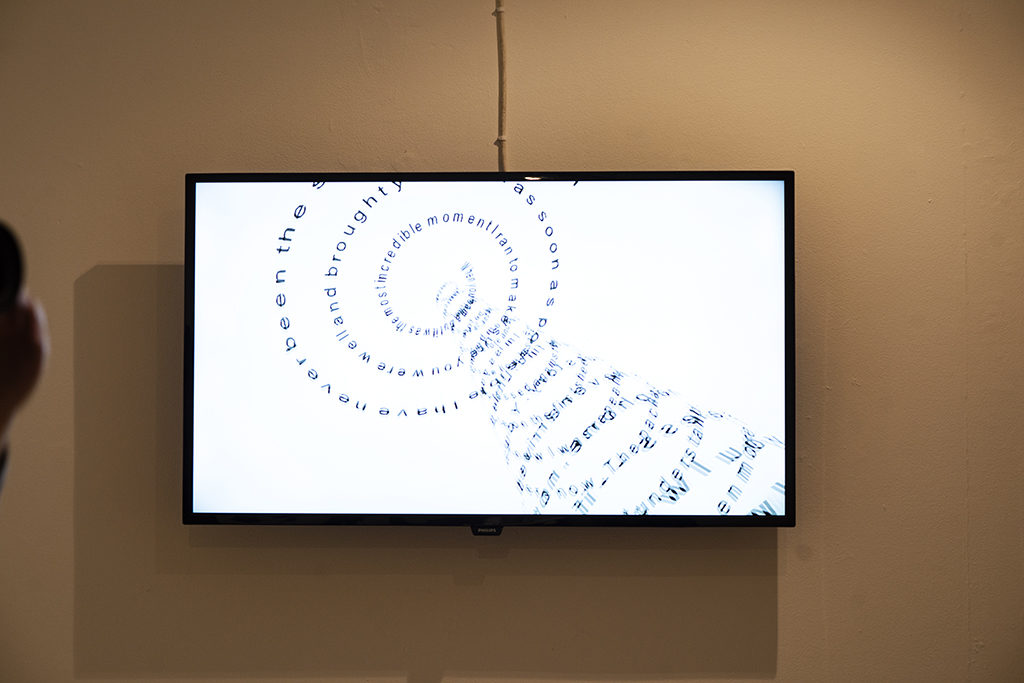

Another remarkable pioneering digital poem on display at Furtherfield, Letter (1996), uses virtual reality markup language to create a three-dimensional spiral of text which the reader can spin, invert, twist and explore from every conceivable angle. The text appears to be a single letter, but turns out to be two letters, one from the artist to his dead grandmother and another to his newly born daughter.

Text and language are perhaps the two technologies which most profoundly shape our lives. By altering our perception and engagement with text, Kac raises questions about the way in which we communicate and understand each other. In his beautiful holopoems, one of which is on display in the Furtherfield exhibition, Kac creates texts which shift and change depending on the angle at which they are viewed. Text technologies frequently give the impression of immutability, but Kac’s holopoems remind us how unstable and deceptive texts may be.

The full range of Kac’s technological exploration is impossible to encompass in a single exhibition, but some sense of it is evident from his website (www.ekac.org). Particularly fascinating is the way in which Kac has explored the poetic possibilities of technologies which are now redundant. Although the platform on which the work was realised is now obsolete, the work nevertheless anticipates contemporary digital cultures. Thus, Kac used the French videotext network Minitel to show the possibilities of network art. He demonstrated the potential of large-scale collaborative works by various pieces using fax. Kac was already experimenting with the potential of telepresence, robotics and wearables in the 1990s.

At each point in these explorations, Kac urges us to engage with these technologies creatively, to use them to create fresh visions, and not simply to accept them as consumers. As a historian, I have long felt that humanities scholars too often passively accept the technological resources and tools made available to them by commercial companies and others. One of the reasons why I believe passionately that humanities scholars should engage more closely with artistic practice is that such a dialogue will foster a more creative and critical approach to the use of digital methods by humanities scholars. The artists whose work I have encountered in the course of my AHRC Fellowship, such as Fabio Lattanzi Antinori, Michael Takeo Magruder, and Katriona Beales as well as pioneers such as Nam June Paik all convey the message that we need to engage creatively with technology. Technology is a threat if we view it passively as an inhuman external force; if we rather seek, like Kac and these other artists, to interrogate, extend and reimagine technology in a creative way we can hope to take greater ownership of it.

This is most spectacularly illustrated in Kac’s bio-art. It is now becoming evident that new biotechnologies will within a short period of time profoundly alter human existence and personality. Kac’s bio-art (following in a tradition which includes the creation of germ pictures by Sir Alexander Fleming) again encourages us to engage creatively with these emerging technologies.

DNA is text and DNA can be poetry of the most profound sort. In a series of works called Genesis (2001), a synthetic gene was created by Kac by translating a sentence from the biblical book of Genesis into Morse Code, and converting the Morse Code into DNA base pairs according to a conversion principle developed by the artist. The sentence chosen was Genesis 1:26: ‘Let man have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over every living thing that moves upon the earth’.

Visitors to the gallery showing Genesis could trigger mutations in the bacteria’s DNA by switching an ultra-violet light on and off. This in turn mutated the text when it was converted back in morse code and then into English. The artist comments that ‘the ability to change the sentence is a symbolic gesture: it means that we do not accept its meaning in the form we inherited it, and that new meanings emerge as we seek to change it’.

Kac’s most well-known work is GFP Bunny (2000) in which an albino rabbit called Alba was bred in a laboratory with a gene causing the rabbit to glow fluorescent green under a blue light. Kac’s image of Alba has become very well-known and was perhaps one of the first iconic art images of the twenty-first century. We will be exploring the cultural phenomenon of Alba in another exhibition at the Horse Hospital called ‘…and the Bunny goes Pop’, opening on 2 June 2018.

The distinctive image of Alba, shown on The Alba Flag (2001) hanging outside Furtherfield during the exhibition, is also a highly poetic image, conveying many messages about identity, the nature of life and belonging, and the increasing intersection of these with technology. Kac’s memories of Alba prompted him to create a wordless language system incorporating rabbit imagery which he called lagoglyphs (from the ancient Greek words ‘lagos’ for hare and ‘glyphe’ for carving).

Kac has now begun a series of Lagoogleglyphs, large lagoglyphs designed to be visible from the satellites which provide the imagery for Google Earth. Lagoogleglyph I (2009) was installed at Oi Futuro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil and Lagoogleglyph II (2015) at Es Baluard Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Palma de Mallorca, Spain. Lagoogleglyph III has been installed in Finsbury Park.

The Lagoogleglyphs encapsulate what is to me the central message of Kac’s work. Google is a vast all-encompassing technology giant which encourages us to consume its services while it makes money from data about us. The way in which Google Earth acts as a panopticon for the world, presenting an idealised sunny view of the planet’s surface, symbolises the hierarchical downward nature of much modern technology.

How can we seek to make our presence felt with the world of mass corporate technology? Painting a huge image in Finsbury Park is an inspired way of intervening in the artificial deracinated corporate view of the human world presented in Google Earth.

When the Arts and Humanities Research Council established its strategic theme of ‘Digital Transformations’ in 2011, the terminology echoed that used in many corporate contexts, and was redolent of improved business processes and data management. Eduardo Kac’s work reminds us that real digital transformations are achieved through creative interrogation of technology and through reimagining how we engage with that technology. Poems turn out to be true drivers of digital transformation.